Abstract

The susceptibility of viridans group streptococci to macrolides was determined. Thirteen isolates (17%) were resistant to erythromycin. Five strains carried an erm gene that was highly homologous to that in Tn917. Four strains had mefE genes that coded erythromycin efflux ability.

Viridans group streptococci, commensal bacteria in the human oral and nasal cavities, are associated with systemic diseases, including infective endocarditis, bacteremia, and pneumonia (2, 5, 6, 10, 12). Macrolide resistance has spread in staphylococci, enterococci, and streptococci (7–9, 11), but little is known about the distribution of the resistance among oral streptococci (12, 19). In this work, clinical isolates of oral and nasal Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis have been tested for susceptibility to macrolides, and resistance genes have been characterized.

Eighty-four streptococcal isolates from patients who visited Tokushima University Hospital between June and December 1995 were studied. These strains were isolated from periodontal pockets, larynx, pharynx, maxillary sinus, and nasal secretion and identified as S. oralis (54 strains), S. mitis (29 strains), Streptococcus sanguis (1 strain), and Streptococcus salivarius (1 strain) by biochemical tests, including the API-20 Strep system (bioMérieux, La Balme des Grottes, France).

The following antibiotics were used: leucomycin and midecamycin (Meiji Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), erythromycin and rokitamycin (Asahi Kasei Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), clarithromycin (Dynabott), azithromycin (Pfizer Pharmaceuticals), and roxithromycin (Hoechst-Marion-Roussel).

MICs were determined by a broth microdilution method in anaerobic MIC broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). Microtiter plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2.

Induction experiments for macrolide resistance were performed by preculture with a sub-MIC of erythromycin. Crude DNA of streptococci was prepared as previously described (13). PCR primers for erm and mefE were designed from published sequences (1) to provide specific PCR products of 530 and 1,218 bp, respectively. The erm primers were 5′-GAAATIGGIIIIGGIAAAGGICA-3′ and 5′-AAYTGRTTYTTIGTRAA-3′, and the mefE primers were 5′-ATGGAAAAATACAACAATTGGAAACGA-3′ and 5′-TTATTTTAAATCTAATTTTCTAACCTC-3′.

Macrolide susceptibility is shown in Table 1. The erythromycin MICs at which 90% of the isolates tested are inhibited (MIC90s) for S. oralis and S. mitis were 8 and 32 μg/ml, respectively. MIC ranges of clarithromycin, azithromycin, and roxithromycin were similar to those of erythromycin. The MIC range of rokitamycin for S. oralis and S. mitis was narrow, with MIC90s of 0.5 and 1 μg/ml, respectively. Among 13 erythromycin-resistant strains (MIC, ≥8 μg/ml), 6 strains were highly resistant to erythromycin; the MICs for them were ≥512 μg/ml (Table 2). All of the strains except O14 were also highly resistant to clarithromycin, azithromycin, and roxithromycin, but intermediately resistant to rokitamycin (MIC, ≥0.5 to ≤2 μg/ml). Strain O14 was intermediately resistant to azithromycin and roxithromycin (MICs, ≥0.5 to ≤2 μg/ml) and sensitive to rokitamycin (MIC, ≤0.25 μg/ml). Seven strains were intermediately resistant to 14- and 15-member macrolides.

TABLE 1.

In vitro activity of macrolide antibiotics for S. oralis and S. mitis

| Organism | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | ||

| S. oralis | Erythromycin | 0.016–>512 | 0.125 | 8 |

| Clarithromycin | 0.016–2048 | 0.031 | 8 | |

| Roxithromycin | ≤0.016–>512 | 0.25 | 8 | |

| Azithromycin | ≤0.016–>512 | 0.5 | 16 | |

| Rokitamycin | 0.031–4 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| S. mitis | Erythromycin | 0.016–>512 | 0.125 | 32 |

| Clarithromycin | 0.016–>512 | 0.031 | 32 | |

| Roxithromycin | ≤0.016–2048 | 0.125 | 64 | |

| Azithromycin | ≤0.016–2048 | 0.5 | 64 | |

| Rokitamycin | 0.031–8 | 0.125 | 1 | |

50% and 90%, MIC50 and MIC90, respectively.

TABLE 2.

MIC of macrolides in the presence and absence of inducera for erythromycin-resistant strains

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) with or without inducerb

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythromycin

|

Rokitamycin

|

Midecamycin

|

Leucomycin

|

Clarithromycinc (−) | Azithromycin (−) | Roxithromycin (−) | PCR product

|

||||||

| − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | erm | mefE | ||||

| S. oralis SO12 | >1,024 | >1,024 | 1 | >256 | 4 | >128 | 8 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | + | − |

| S. mitis SO13 | >1,024 | >1,024 | 2 | >256 | 16 | >128 | 16 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | + | − |

| S. mitis E2 | 512 | 512 | 1 | 256 | 4 | >128 | 4 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | + | − |

| S. oralis O14 | 512 | >512 | <0.125 | >256 | <0.063 | >128 | <0.25 | >512 | 256 | 1 | 2 | + | + |

| S. oralis E21 | 512 | >512 | 1 | 512 | 2 | >128 | 4 | >512 | 256 | 64 | 2 | + | − |

| S. mitis E3 | 512 | >128 | 8 | 16 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >256 | 64 | >512 | >512 | − | + |

| S. mitis E11 | 32 | 16 | <0.031 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 32 | 64 | 64 | − | − |

| S. oralis E17 | 16 | 16 | 0.25 | <0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 8 | 32 | 32 | − | + |

| S. mitis E27 | 16 | 8 | <0.25 | <0.25 | <0.031 | <0.063 | <0.031 | <0.125 | 32 | >32 | >32 | − | − |

| S. oralis O24 | 8 | 8 | <0.25 | <0.25 | 0.125 | <0.063 | 0.063 | <0.125 | 4 | 32 | 16 | − | + |

| S. mitis E10 | 8 | NDc | 0.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 16 | 16 | − | − |

| S. mitis E18 | 8 | ND | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 16 | 8 | − | − |

| S. mitis E30 | 8 | 32 | 0.125 | <0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | <0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 32 | 32 | + | − |

The inducing concentration of erythromycin was 0.25 μg/ml.

−, absence of inducer; +, presence of inducer. Note that the MICs of clarithromycin, azithromycin, and roxithromycin in the presence of inducer were not determined.

ND, not determined.

As shown in Table 2, all erythromycin-resistant strains were more sensitive to rokitamycin than other macrolides. To determine whether resistance could be induced, MICs of 16-member macrolides for cells grown in medium with or without a sub-MIC of erythromycin were examined. Highly resistant strains SO12, SO13, O14, E2, and E21 were induced to develop resistance to rokitamycin, midecamycin, and leucomycin. Strain E3 was highly resistant to midecamycin and leucomycin, even when cultured without erythromycin, and rokitamycin resistance was not induced. The intermediately resistant strains, O24, E17, E11, E27, and E30, did not develop resistance to 16-member macrolides after erythromycin induction.

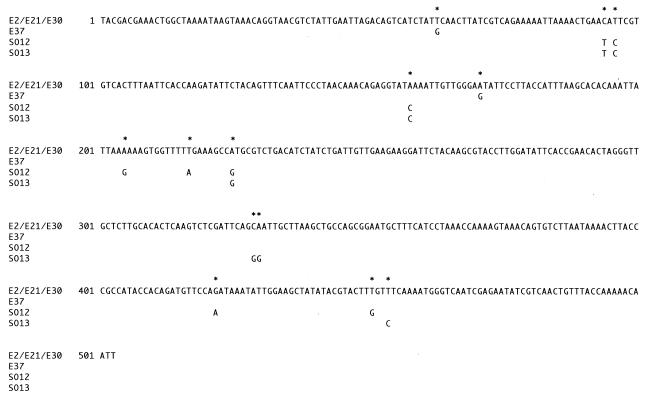

To clarify the mechanisms of resistance, PCR amplification of macrolide-resistant genes was performed. PCR primers for the erm (23S rRNA methylase) gene were designed based on the sequence of corresponding genes from other organisms. The highly resistant strains gave a distinct band of the expected 530-bp size from position 103 to position 633 of the erm gene. PCR products from these strains and S. salivarius E37 were sequenced (Fig. 1). Sequences from strains E2, E21, and E30 were identical to those of the gene encoding the rRNA methylase on transposon Tn917 (4). Those from other strains had ∼98% homology to Tn917. The nucleotide changes in strains SO12, SO13, and E37 resulted in six, four, and two amino acid alterations, respectively, but did not affect the reading frame. Primer sets for the mefE gene were designed based on the sequence of that gene in S. pneumoniae (GenBank U83667). The intermediately resistant strains O24, E17, and E3 and highly resistant strain O14 gave the expected band (approximately 1,200 bp) for the mefE gene encoding the macrolide efflux pump (18). The sequences of DNA obtained from PCR amplification for mefE in strains O24, E3, and E17 were analyzed. These sequences were identical to those at positions 30 to 1190 of the corresponding mefE gene. Less erythromycin accumulated in mefE-positive strain E17 than in mefE-negative strain E1 15 min after the addition of [N-methyl-14C]erythromycin (data not shown). Accumulation of erythromycin in the mefE-positive strain was restored by addition of proton conductors, suggesting that a macrolide efflux system exists in strain E17. For genes encoding macrolide-inactivating enzyme, ereA, ereB, and mphE and macrolide efflux genes msr and mefA (17), PCR amplification was performed with DNA from macrolide-resistant strains; however, no PCR products have been detected.

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequences of PCR products obtained with oral streptococci by using an erm primer set. The sequences in strains E2, E21, and E30 were identical to that from the site of the E. faecalis ermB gene. In strains E37, SO12, and SO13, only the base changes are shown (highlighted by asterisks).

Although erm genes encoding rRNA methylase are present in various organisms, such as Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus, and macrolide resistance is widespread in bacteria associated with humans (4, 15, 17), the potential reservoir for erm genes is unknown. It has been reported that the genes lie on various transposable elements or conjugal plasmids (4, 11, 14). In the present study, we showed that the nucleotide sequences of PCR products obtained with erm primers from some strains were identical to the rRNA methylase gene in Enterococcus faecalis transposon Tn917, while those from S. oralis SO12 and S. mitis SO13 were highly homologous with the ermB gene from conjugal plasmid pIP501 of Streptococcus agalactiae (3, 4). In the upstream region, the sequence homologous to LR, an internal sequence of Tn917 has been found (16) (data not shown). S. oralis and S. mitis are major species in the oral and nasal normal flora. The results of this study suggest the transmission of macrolide-resistant genes between oral streptococci and other more virulent streptococci.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kurumi Sugawara, Etsuko Lee, Noriko Hayashi, and Fumiko Aikawa for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (no. 10671703) to T.O. from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Molinas C, Mabilat C, Courvalin P. Detection of erythromycin resistance by the polymerase chain reaction using primers in conserved regions of erm rRNA methylase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2024–2026. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.10.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awada A, van der Auwera P, Meunier F, Daneau D, Klastersky J. Streptococcal and enterococcal bacteremia in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:33–48. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brantl S, Kummer C, Behnke D. Complete nucleotide sequence of plasmid pGB3631, a derivative of the Streptococcus agalactiae plasmid pIP501. Gene. 1994;142:155–156. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisson-Noël A, Arthur M, Courvalin P. Evidence for natural gene transfer from gram-positive cocci to Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1739–1745. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1739-1745.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford I, Russell C. Streptococci isolated from the bloodstream and gingival crevice of man. J Med Microbiol. 1983;16:263–269. doi: 10.1099/00222615-16-3-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas C W I, Heath J, Hampton K K, Preston F E. Identity of viridans streptococci isolated from cases of infective endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 1993;39:179–182. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-3-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esposito S, Noviello S, Ianniello F, D'Errico G. Erythromycin resistance in group A beta hemolytic streptococcus. Chemotherapy. 1998;44:385–390. doi: 10.1159/000007148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein F W, Acar J F The Alexander Project Collaborative Group. Antimicrobial resistance among lower respiratory tract isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: results of a 1992–93 western Europe and USA collaborative surveillance study. The Alexander Project Collaborative Group. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:71–84. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.suppl_a.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton-Miller J M T. In-vitro activities of 14-, 15- and 16-membered macrolides against gram-positive cocci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;29:141–147. doi: 10.1093/jac/29.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knox K W, Hunter N. The role of oral bacteria in the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis. Aust Dent J. 1991;36:286–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1991.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krah E R, III, Macrina F L. Genetic analysis of the conjugal transfer determinants encoded by the streptococcal broad-host-range plasmid pIP501. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6005–6012. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6005-6012.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreillon P, Overholser C D, Malinverni R, Bille J, Glauser M P. Predictors of endocarditis in isolates from cultures of blood following dental extractions in rats with periodontal disease. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:990–995. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ono T, Hirota K, Nemoto K, Fernandez E J, Ota F, Fukui K. Detection of Streptococcus mutans by PCR amplification of spaP gene. J Med Microbiol. 1994;41:231–235. doi: 10.1099/00222615-41-4-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins J B, Youngman P J. A physical and functional analysis of Tn917, a Streptococcus transposon in the Tn3 family that functions in Bacillus. Plasmid. 1984;12:119–138. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Projan S J, Monod M, Narayanan C S, Dubnau D. Replication properties of pIM13, a naturally occurring plasmid found in Bacillus subtilis, and of its close relative pE5, a plasmid native to Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5131–5139. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5131-5139.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw J H, Clewell D B. Complete nucleotide sequence of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B-resistance transposon Tn917 in Streptococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:782–796. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.782-796.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tait-Kamradt A, Clancy J, Cronan M, Dib-Hajj F, Wondrack L, Yuan W, Sutcliffe J. mefE is necessary for the erythromycin-resistant M phenotype in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2251–2255. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teng L J, Hsueh P R, Chen Y C, Ho S W, Luh K T. Antimicrobial susceptibility of viridans group streptococci in Taiwan with an emphasis on the high rates of resistance to penicillin and macrolides in Streptococcus oralis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:621–627. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.6.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]