Abstract

GAR-936, a new glycylcycline, had lower MICs (≤0.016 to 0.125 μg/ml) for 201 penicillin- and tetracycline-susceptible and -resistant pneumococcal strains than tetracycline (≤0.06 to 128 μg/ml), minocycline (≤0.06 to 16.0 μg/ml), or doxycycline (≤0.06 to 32.0 μg/ml). GAR-936 was also bactericidal against 11 of 12 strains tested at the MIC after 24 h, with significant kill rates at earlier time points.

The incidence of pneumococcal resistance to penicillin G and other ß-lactam and non-ß-lactam compounds has increased worldwide at an alarming rate (1, 6, 7). In the United States, a recent survey of 1,476 strains showed that 49.6% were penicillin susceptible, 17.9% were of intermediate resistance (penicillin intermediate), and 32.5% were penicillin resistant. Macrolide MICs rose with those of penicillin G, with an overall macrolide resistance level of 33% (8).

Resistance to conventional oral tetracyclines (including minocycline and doxycycline) occurs with increased frequency among penicillin-intermediate and -resistant pneumococci, and genes coding for macrolide and tetracycline resistance are carried on the same transposon (6, 7). GAR-936 is a new broad-spectrum parenteral glycylcycline. Preliminary studies have shown that this drug is active against penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci (13, 15).

This study compares the activity of GAR-936 against 201 penicillin-susceptible, -intermediate, or -resistant pneumococcal strains with those of three other tetracyclines, four ß-lactams, clarithromycin, and vancomycin. Additionally, the activities of these compounds against 12 penicillin-susceptible and -resistant strains of pneumococci were determined by the broth MIC and time-kill methods.

For determination of MICs by agar dilution, 51 penicillin-susceptible, 72 penicillin-intermediate, and 78 penicillin-resistant strains of pneumococci were utilized. For time-kill studies, four penicillin-susceptible, four penicillin-intermediate, and four penicillin-resistant strains were tested; of these, five were tetracycline susceptible (MIC, ≤2.0 μg/ml), 1 was tetracycline intermediate (MIC, 4.0 μg/ml), and six were tetracycline resistant (MIC, ≥8.0 μg/ml).

The agar dilution method used in this study to determine MICs of various antimicrobial agents for 201 pneumococcal strains has been used routinely for many years by our group (6, 7); Mueller-Hinton agar (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 5% sheep blood was employed. Microbroth MIC determinations for 12 strains were performed in accordance with the protocol recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (9). Standard quality control strains, including Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 (9), were included in each run of agar and broth dilution MIC determinations. All MIC studies were performed in air. All strains, recently isolated from stocks stored at −70°C and subcultured twice, grew in air and did not require added CO2 for growth. The susceptibility patterns of these strains are representative of those commonly encountered in the United States (8).

For time-kill studies, methods described previously were used (11, 12). The final inoculum was 5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml. Growth controls with inoculum but no antibiotic were included with each experiment (11, 12). Viable-cell counts of antibiotic-containing suspensions were performed according to standard methods (11, 12). Colony counts were performed on plates yielding 30 to 300 colonies. The lower limit of sensitivity of colony counts was 300 CFU/ml. As mentioned above, all incubations were in ambient air without added CO2.

Time-kill assays were analyzed by determining the number of strains which yielded a Δlog10 CFU/ml of −1, −2, and −3 at 0, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h compared to counts at time zero. Antimicrobial agents were considered bactericidal at the lowest concentration that reduced the original inoculum by ≥3 log10 CFU/ml (99.9%) at each of the time periods, and they were considered bacteriostatic if the inoculum was reduced by 0 to 3 log10 CFU/ml. With the sensitivity threshold and inocula used in these studies, no problems were encountered in delineating 99.9% killing when it occurred. The problem of bacterial carryover was addressed by dilution, as described previously (11, 12). For tetracycline and clarithromycin time-kill testing, only strains with MICs of <8.0 and <4.0 μg/ml, respectively, were tested. In all cases, growth controls grew satisfactorily, without spontaneous autolysis.

The results of agar dilution MIC testing are presented in Table 1. GAR-936 had lower MICs (≤0.016 to 0.125 μg/ml) than tetracycline (≤0.06 to 128 μg/ml), minocycline (≤0.06 to 16.0 μg/ml), and doxycycline (≤0.06 to 32.0 μg/ml) against all strains. MICs of all ß-lactams rose with those of penicillin G, with imipenem being the most active, followed by meropenem, ceftriaxone, and amoxicillin. Macrolide and tetracycline resistance occurred mainly in penicillin-intermediate and -resistant strains, and all strains were susceptible to vancomycin.

TABLE 1.

Agar dilution MICs for 201 pneumococcal isolates

| Drug | Penicillin susceptibility of straina | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50b | MIC90c | ||

| Penicillin | S | ≤0.008–0.06 | ≤0.016 | 0.03 |

| I | 0.125–1.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | |

| R | 2.0–>8.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | |

| GAR-936 | S | ≤0.016–0.125 | 0.03 | 0.125 |

| I | ≤0.016–0.125 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| R | ≤0.016–0.125 | 0.06 | 0.125 | |

| Tetracycline | S | ≤0.06–64.0 | 0.25 | 32.0 |

| I | ≤0.06–64.0 | 1.0 | 64.0 | |

| R | ≤0.25–128.0 | 32.0 | 64.0 | |

| Minocycline | S | ≤0.06–16.0 | 0.06 | 8.0 |

| I | ≤0.06–16.0 | 0.25 | 16.0 | |

| R | ≤0.06–16.0 | 4.0 | 16.0 | |

| Doxycycline | S | 0.03–16.0 | 0.125 | 8.0 |

| I | ≤0.06–32.0 | 0.5 | 8.0 | |

| R | 0.125–16.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | |

| Amoxicillin | S | ≤0.008–0.25 | 0.016 | 0.03 |

| I | ≤0.016–2.0 | 0.125 | 1.0 | |

| R | 0.5–4.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | S | ≤0.008–1.0 | 0.016 | 0.03 |

| I | ≤0.016–2.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | |

| R | 0.25–8.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |

| Clarithromycin | S | ≤0.016–>128.0 | 0.03 | 8.0 |

| I | ≤0.016–>128.0 | 0.06 | >128.0 | |

| R | ≤0.016–>128.0 | 1.0 | >128.0 | |

| Imipenem | S | ≤0.008–0.25 | ≤0.008 | 0.016 |

| I | ≤0.008–0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 | |

| R | 0.03–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| Meropenem | S | ≤0.008–0.5 | 0.016 | 0.03 |

| I | ≤0.016–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| R | 0.125–2.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | |

| Vancomycin | S | ≤0.06–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| I | ≤0.06–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| R | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

S, penicillin susceptible; I, penicillin intermediate; R, penicillin resistant.

MIC50, MIC at which 50% of the isolates tested were inhibited.

MIC90, MIC at which 90% of the isolates tested were inhibited.

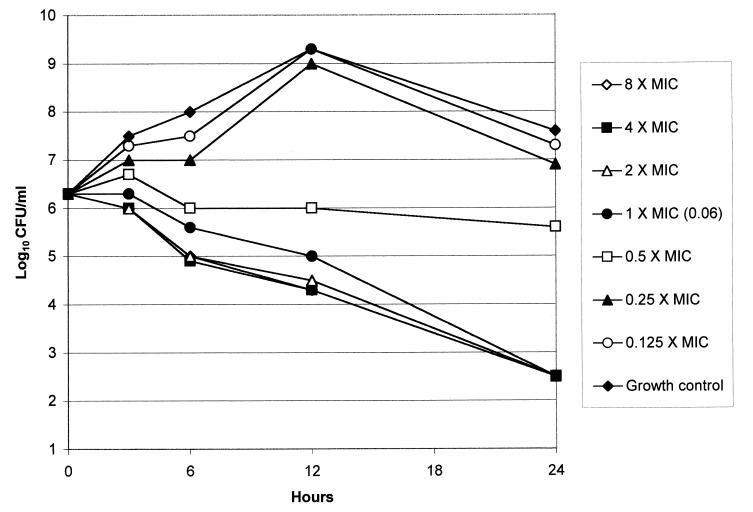

Microbroth MICs of the 12 strains tested by the time-kill method were either identical to or differed by one dilution from those obtained by agar dilution (Table 2). Time-kill results are presented in Table 3. GAR-936 was bactericidal at the MIC after 24 h for 11 of the 12 strains tested; the remaining strain (for which the GAR-936 MIC was 0.06 μg/ml) was killed at eight times the MIC (0.5 μg/ml). GAR-936 showed significant kill rates at earlier time periods: at 12 h, 90% killing of all 12 strains occurred at twice the MIC, while after 6 h, 90% killing of all strains occurred at four times the MIC. The killing rates of other tetracyclines for the six susceptible strains were slightly lower than those of GAR-936. The bactericidal activities of ß-lactams were similar, with uniform bactericidal activity being exhibited at twice the MIC for amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, and imipenem and at eight times the MIC for meropenem after 24 h. Clarithromycin was bactericidal against six of seven strains with clarithromycin MICs of <4.0 μg/ml at twice the MIC after 24 h; vancomycin was bactericidal against 11 of 12 strains at twice the MIC at the same time point. The kill kinetics of GAR-936 against a tetracycline-resistant strain is depicted in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Microbroth MICs for 12 strains tested by the time-kill method

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml) for straina:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1(S) | 2(S) | 3(S) | 4(S) | 5(I) | 6(I) | 7(I) | 8(I) | 9(R) | 10(R) | 11(R) | 12(R) | |

| Penicillin | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| GAR-936 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Tetracycline | 64.0 | 0.5 | 64.0 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 64.0 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 32.0 | 32.0 | 1.0 | 32.0 |

| Minocycline | 16.0 | 0.125 | 8.0 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 64.0 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 0.25 | 4.0 |

| Doxycycline | 8.0 | 0.25 | 16.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 16.0 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 8.0 |

| Amoxicillin | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.125 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Clarithromycin | >64.0 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.03 | >64.0 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.03 | >64.0 | >64.0 | 0.03 | >64.0 |

| Imipenem | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Meropenem | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Vancomycin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

S, penicillin susceptible; I, penicillin intermediate; R, penicillin resistant.

TABLE 3.

Results of time-kill assays of 12 pneumococcal strains

| Drug and concn | No. of strains killed by time point, with Δlog10 CFU/ml (from time zero value) of:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h

|

6 h

|

12 h

|

24 h

|

|||||||||

| −1 | −2 | −3 | −1 | −2 | −3 | −1 | −2 | −3 | −1 | −2 | −3 | |

| GAR-936 | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 7 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 4× MIC | 6 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 2× MIC | 5 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| MIC | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| 0.5× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Tetracyclinea | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 4× MIC | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 2× MIC | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 0.5× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Minocyclinea | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 4× MIC | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 2× MIC | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| MIC | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| 0.5× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Doxycyclinea | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 4× MIC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 2× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 0.5× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Amoxicillin | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 10 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 4× MIC | 9 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 2× MIC | 8 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| MIC | 5 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| 0.5× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Ceftriaxone | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 8 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 4× MIC | 8 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 2× MIC | 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| MIC | 5 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| 0.5× MIC | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clarithromycinb | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 4 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| 4× MIC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| 2× MIC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| MIC | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 4 |

| 0.5× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Imipenem | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 12 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 4× MIC | 11 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 2× MIC | 11 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| MIC | 10 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 9 |

| 0.5× MIC | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Meropenem | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 11 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 4× MIC | 9 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 2× MIC | 6 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| MIC | 6 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| 0.5× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Vancomycin | ||||||||||||

| 8× MIC | 7 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 4× MIC | 7 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 2× MIC | 7 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| MIC | 6 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| 0.5× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

Only strains with tetracycline MICs of <8.0 μg/ml were tested.

Only strains with clarithromycin MICs of <4.0 μg/ml were tested.

FIG. 1.

Graphical depiction of GAR-936 kill kinetics versus a tetracycline-resistant (MIC, 64.0 μg/ml) strain of S. pneumoniae.

The glycylcyclines are semisynthetic tetracyclines exhibiting a broad spectrum of activity compared to conventional tetracyclines, with activity against gram-positive and -negative aerobes, anaerobes, chlamydiae, and mycoplasmas (2–5, 10, 14, 16, 17). GAR-936 is a newly described 9-t-butylglycylamido derivative of minocycline. This compound possesses activity against isolates possessing the two major determinants of tetracycline resistance, ribosomal protection and efflux (13, 15).

In the present study, MICs of GAR-936 against all pneumococci, irrespective of their susceptibility to ß-lactams, macrolides, or other tetracyclines, ranged between ≤0.016 and 0.125 μg/ml. These results are similar to those obtained by Petersen et al (13). Bactericidal activity was also found after 24 h for all 12 strains tested at ≤0.5 μg/ml. At the MIC, after 24 h, GAR-936 showed better kill kinetics, relative to the MIC, than other tetracyclines and was bactericidal for more strains than were the ß-lactams tested. It should be emphasized, however, that he relatively small number of strains tested makes interpretation of relatively small differences in kill kinetics problematic. More strains must be tested before such conclusions can be considered valid. Although tetracyclines are traditionally thought to be bacteriostatic agents, the present study shows that GAR-936 (and other tetracyclines, relative to their MICs) may be bactericidal after 24 h.

Of the other tetracyclines tested, minocycline and doxycycline had lower MICs than tetracycline; the significance of this phenomenon is unknown at this time. The MICs of and time-kills results for the other compounds tested are similar to those reported by others (7, 11, 12).

Although the results of toxicologic and pharmacokinetic studies are awaited, GAR-936 appears to be a promising new agent for treatment of infections caused by drug-resistant pneumococci.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from Wyeth-Ayerst Research Laboratories, Pearl River, N.Y.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelbaum P C. Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae—an overview. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:77–83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergeron J, Ammirati M, Danley D, James L, Norcia M, Retsema J, Strick C A, Su W-G, Sutcliffe J, Wondrack L. Glycylcyclines bind to the high-affinity tetracycline ribosomal binding site and evade Tet(M)- and Tet(O)-mediated ribosomal protection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2226–2228. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eliopoulos G M, Wennersten C B, Cole G, Moellering R C. In vitro activities of two glycylcyclines against gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:534–541. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.3.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein F W, Kitzis M D, Acar J F. N,N-Dimethylglycyl-amido derivative of minocycline and 6-demethyl-6-desoxytetracycline, two new glycylcyclines highly effective against tetracycline-resistant gram-positive cocci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2218–2220. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton-Miller J M T, Shah S. Activity of glycylcyclines CL 329998 and CL 331002 against minocycline-resistant and other strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1171–1175. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs M R. Treatment and diagnosis of infections caused by drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:119–127. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Antibiotic-resistant pneumococci. Rev Med Microbiol. 1995;6:77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs M R, Bajaksouzian S, Zilles A, Lin G, Pankuch G A, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibilities of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae to 10 oral antimicrobial agents based on pharmacodynamic parameters: 1997 U.S. surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1901–1908. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 3rd ed. 1997. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nord C E, Lindmark A, Persson I. In vitro activity of DMG-Mino and DMG-DM Dot, two new glycylcyclines, against anaerobic bacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:784–786. doi: 10.1007/BF02098471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pankuch G A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Study of comparative antipneumococcal activities of penicillin G, RP 59500, erythromycin, sparfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin by using time-kill methodology. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2065–2072. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pankuch G A, Lichtenberger C, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Antipneumococcal activities of RP 59500 (quinupristin-dalfopristin), penicillin G, erythromycin, and sparfloxacin determined by MIC and rapid time-kill methodologies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1653–1656. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen P J, Jacobus N V, Weiss W J, Sum P E, Testa R T. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of a novel glycylcycline, the 9-t-butylglycylamido derivative of minocycline (GAR-936) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:738–744. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Testa R T, Petersen P J, Jacobus N V, Sum P-E, Lee V J, Tally F P. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of the glycylcyclines, a new class of semisynthetic tetracyclines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2270–2277. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Ogtrop M L, Andes D, Craig W A, Vesga O. Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. In vivo activity of two glycylcyclines (GAR-936 and WAY 152,288) against tetracycline-sensitive and -resistant bacteria, abstr. F-133; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss W J, Jacobus N V, Petersen P J, Testa R T. Susceptibility of enterococci, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae to the glycylcyclines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:225–230. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wise R, Andrews J M. In vitro activities of two glycylcyclines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1096–1102. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]