Abstract

Objective:

Skin fibrosis places an enormous burden on patients and society, but disagreement exists over methods to quantify severity of skin scarring. A suction cutometer measures skin elasticity in vivo, but it has not been widely adopted because of inconsistency in data produced. We investigated variability of several dimensionless parameters generated by the cutometer to improve their precision and accuracy.

Approach:

Twenty adult human subjects underwent suction cutometer measurement of normal skin (NS) and fibrotic scars (FS). Using Mode 1, each subject underwent five trials with each trial containing four curves. R0/2/5/6/7 and Q1/2/3 data were collected. Analyses were performed on these calculated parameters.

Results:

R0/2/5/6/7 and Q1/2 parameters from curves 1 to 4 demonstrated significant differences, whereas these same parameters were not significantly different when only using curves 2–4. Individual analysis of all parameters between curve 1 and every subsequent curve was statistically significant for R0, R2, R5, R6, R7, Q1, and Q2. No differences were appreciated for parameter Q3. Comparison between NS and FS were significantly different for parameters R5, Q1, and Q3.

Innovation:

Our study is the first demonstration of accurate comparison between NS and FS using the dimensionless parameters of a suction cutometer.

Conclusions:

Measured parameters from the first curve of each trial were significantly different from subsequent curves for both NS and FS. Precision and reproducibility of data from dimensionless parameters can therefore be improved by removing the first curve. R5, Q1, and Q3 parameters differentiated NS as more elastic than FS.

Keywords: cutometer, skin elasticity, skin elasticity measurement, in vivo skin elasticity, viscoelasticity, skin fibrosis

Derrick C. Wan, MD

Arash Momeni, MD

INTRODUCTION

Skin fibrosis is a multifaceted problem for both patients and physicians alike, culminating in billions of dollars in annual costs for health care systems worldwide.1,2 Fibrosis of the skin can be a sequela of numerous etiologies: radiation therapy for oncologic treatment, previous incisions or wounds, and hyperfibrotic syndromes such as systemic sclerosis or any number of autoimmune diseases.3–5 On gross examination, decreased elasticity, contracture or deformity of skin and surrounding soft tissue, and discoloration of the skin all signify qualitative characteristics of fibrosis. However, techniques to quantify the exact amount of skin stiffness present are much more difficult to perform and often subjective. Histologically, fibrosis can be quantified as a measure of collagen deposition, dermal thickness, and linear organization of collagen fibers, but to histologically examine human skin would require multiple biopsy sites within scarred, compromised fields, which may result in nonhealing wound formation, infection, and impaired cosmesis.6

Other methods to quantify fibrosis in skin include in situ tensile tests, skin pinch test/tissue elevation tests, torsional tests, ballistometry, and indentation. Various scales have been developed as well to attempt to grossly quantify the amount of fibrosis within damaged skin such as the modified Rodnan skin score, patient and observer scar assessment scale, Vancouver scar scale, visual analog scale, and the Manchester scar scale.7–9 However, all these techniques are still subject to a large degree of subjectivity, making them difficult to objectively quantify skin fibrosis in vivo. Therefore, identifying a noninvasive technique that would better assist in standardizing and grossly quantifying elasticity levels within hyperfibrotic human skin is paramount to advancing the field of fibrosis research and to the development of biotherapeutics for fibrosis.7,10

Cutometer devices such as the Dual MPA 580, SEM 474, and SEM 575 (Courage+Khazaka, Köln, Germany) have been used sporadically in clinical settings to measure skin elasticity. These devices apply a specified amount of negative pressure on the surface of the skin to draw skin into the circular aperture of the measurement probe. This allows for optical assessment of skin displacement using a laser. The amount of tissue elevation and speed of return when negative pressure is released represents the amount of elasticity of the skin drawn into the probe. Although these devices could be useful, their results are often widely variable owing to numerous factors: offset—the amount of skin within the probe before any applied suction, heterogeneity in human skin, operator variability, operator and subject movement, software settings, and probe and device maintenance.11–13 Previous studies have investigated probe pressure and intersite variability while using the cutometer.14,15 Although these studies have helped delineate the potential uses of this device, the majority of data is often too variable for any routine scientific or clinical use.

To standardize and utilize the data generated by the cutometer, we hypothesize that eliminating the first curve measured with the cutometer will increase the precision and accuracy of this device to determine elasticity of both normal and fibrotic human skin. Furthermore, our preliminary data demonstrated that normal skin (NS) is more elastic than fibrotic skin, consistent with previous studies regarding scar fibrosis.16–18 However, without the need for invasive techniques such as biopsies or specimen sacrifice, or the use of subjective visual analog scales like the ones listed previously, we hypothesize that we can better quantify the amount of in vivo fibrosis longitudinally by using the dimensionless parameters of the cutometer.

INNOVATION

Suction cutometers have been used to delineate skin elasticity since the 1980s, mainly utilizing the R0 and R2 parameters. However, these devices have been limited as these two parameters have been the only verified, reproducible data to be generated and analyzed. Furthermore, these values are still subject to factors such as offset and skin thickness, which may introduce variability. The novelty of our study is the ability to not only generate precise and accurate data using the dimensionless parameters R5, R6, R7, Q1, Q2, and Q3, but also to validate these parameters by demonstrating their ability to differentiate NS as more elastic compared with fibrotic scars (FS), especially in the R5, Q1, and Q3 parameters.

Clinical problem addressed

FS are secondary to numerous etiologies: surgical incisions, radiation therapy, burn wounds, or hyperfibrotic syndromes such as systemic sclerosis. These scars significantly decrease the cosmesis and functionality of their affected sites, in addition to the affected individual's quality of life. With the ability to improve in vivo, noninvasive skin elasticity measurements with the suction cutometer, we allow both researchers and clinicians in the field of wound healing to exponentially increase the amount of data to better study, understand, monitor, diagnose, and treat these diseases without the risks of repetitive invasive diagnostic methods like skin biopsies.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Personnel

A two-person team was used to operate the cutometer with one investigator managing the computational software and the other investigator handling the probe itself.

Equipment and software set-up

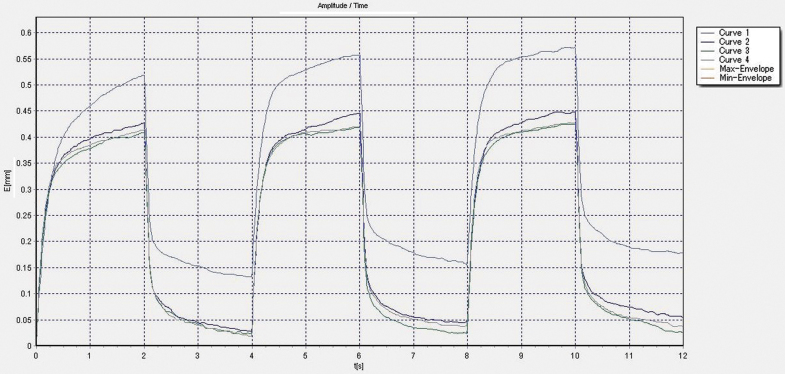

The software was run using a Windows® operating system. Skin elasticity was measured using Mode 1 (time-strain mode) on the MPA Q software. Mode 1 is characterized by a constant pressure value during a predefined suction time (2 s) immediately followed by a predefined interval of relaxation time (2 s), which we considered one full cycle. A full curve was composed of three cycles of suction/relaxation, thus 12 s total per curve. One full trial was composed of 4 curves without removing or altering probe position during the measurement of those 4 curves (Fig. 1). The force of probe suction was set at 300 mbar (30 kPa).

Figure 1.

A representative graph of 4 curves taken using the Mode 1 setting.

Experimental design

Adult, healthy human subjects (n = 20) between the ages of 23 and 35 years, with equal number of men and women, volunteered to be studied. All subjects were included in both the NS and fibrotic scar cohorts of this study. The inclusion criteria for FS were procedure date at least 6 months prior or greater to insure completely healed incisions, incisions rated at least 3 or higher on the Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale by a single-blinded, board-certified plastic surgeon, nonhypertrophic scars, scars >1 cm in length, and any anatomic location excluding the head or neck to insure normal physiologic skin for testing in the cervical paraspinal area. All subjects were informed of the risks and benefits of the procedure, and signed written informed consent before enrollment in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Stanford University, and the protocols used in this study were approved by the Administrative Panel on Human Subjects in Medical Research at Stanford University (IRB #60284).

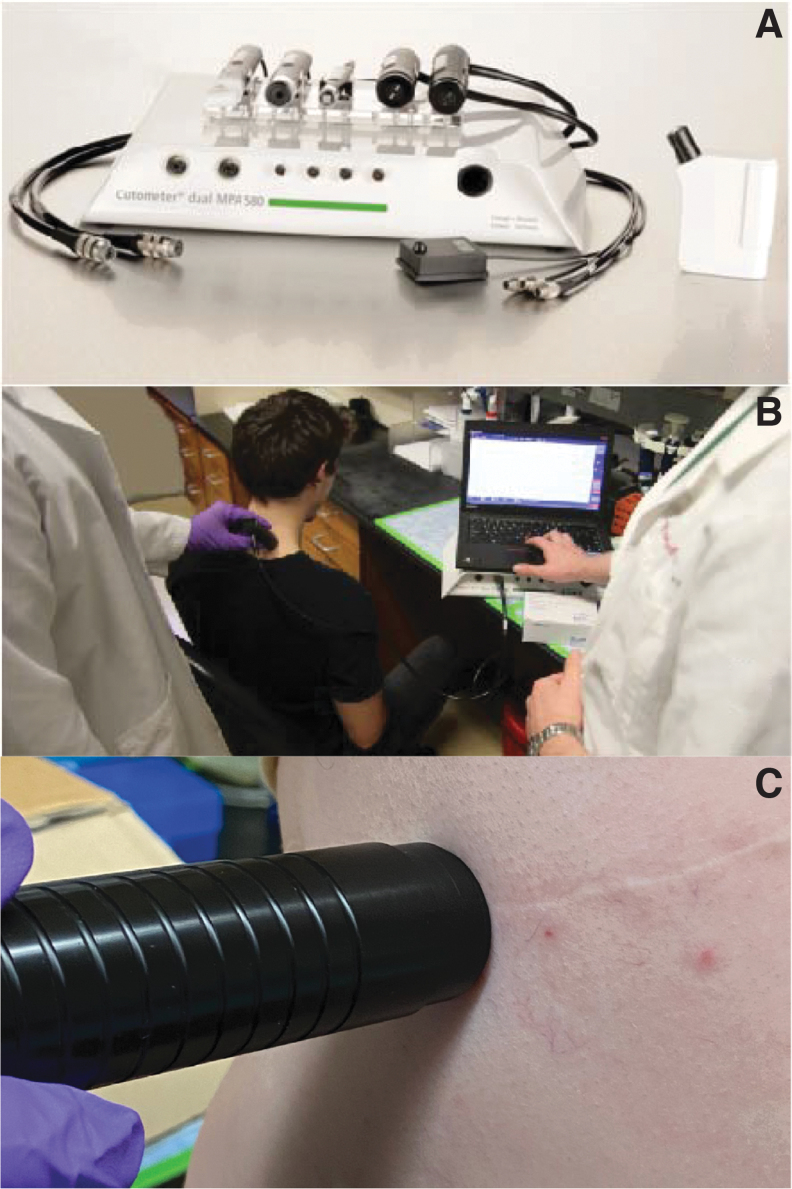

All testing was performed on the same date in February 2021 in a humidity and temperature-controlled environment with the temperature maintained at 23°C and humidity at 35%. All subjects had also undergone acclimatization to this environment for at least 1 h before testing. The Cutometer® Dual MPA 580 was stored and utilized in the same climate-controlled environment (Fig. 2A). A probe with an 8 mm aperture was used and, before initiation of the experiment, the inside of the probe was first cleaned with the manufacturer-provided cleaning solution and brush. The manufacturer-provided double-sided stickers were then applied to the probe to assist with creating a vacuum seal between the surface of the probe and the surface of the skin. All hair was removed from the subject at the testing site to facilitate creation of a vacuum seal between the testing site and the probe. This site was then cleaned with alcohol prep swabs and allowed to dry for at least 5 min to remove any residual sweat, oil, debris, hair, epithelial cells, or cosmetics. After this drying period, testing was performed by the same two-person investigation team for all subjects.

Figure 2.

(A) Cutometer Dual MPA 580 with multiple probes, (B) the two-investigator team performing cervical cutometer measurements, and (C) an example of suction cutometer data collection on FS. FS, fibrotic scar.

For NS, testing was performed on skin overlying the upper cervical paraspinal area, 2.5 cm off the midline, as this area provided a solid, relatively uniform muscular surface underlying the skin and has been previously described to be most reliable when studying normal tissue with a cutometer.19 The subject was seated at a 90° angle at the hip and a 10° tilt downward of the head (Fig. 2B). For FS, incisional scars were identified on each subject. Subjects were positioned to maintain a relatively flat surface underlying the fibrotic skin (Fig. 2C). Sites of NS analogous to FS locations were also measured as controls for the FS cohort. For both NS and FS, the probe was then placed exactly perpendicular to the selected skin sample, pressing firmly to create an adhesive seal between the skin and the probe. After a seal was created between the probe and the sample site, only the weight of the probe itself (∼80 g) was used while collecting data to minimize offset for measuring skin elasticity. Five full trials were then performed on the same location with the probe being removed and the sticker replaced after each trial. The investigator holding the probe was blinded to the results of the experiment. The second investigator utilizing the computational software was unable to be blinded to the results because of the nature of the experiment.

Parameters generated

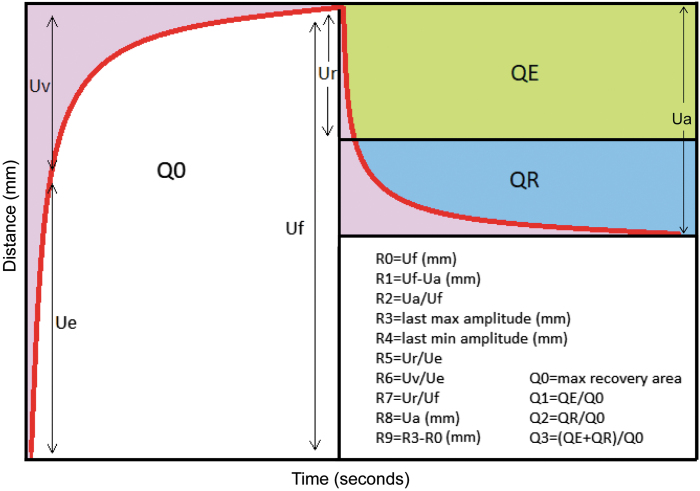

R0 correlates to the skin pliability/firmness and represents the passive behavior of the skin to the suction force. This parameter is measured from the highest point of amplitude at the end of the suction phase to the baseline reading (R0 = Uf). The ability of the skin to recover to its initial state is defined as R1. R1 = Uf − Ua, which represents the residual deformation in millimeters at the end of relaxation phase. The R2 parameter is the gross elasticity/viscoelasticity, which is the skin's resistance to the mechanical suction force versus its ability to recover (R2 = Ua/Uf). R3 (the maximum amplitude of the last suction cycle in the last curve of a trial), R4 (the last minimum amplitude of the last cycle in the last curve of a trial), and R9 (R9 = R3 − R0) all represent the tiring effects or fatigue of skin after repeated suction. R5 represents the net elasticity (R5 = Ur/Ue), meaning the higher the value the more elastic the skin. The portion of the viscoelasticity (R6 = Uv/Ue) represents the distensibility of the elastin fibers. R7 is the immediate recovery in the first 0.1 s compared with the amplitude after suction (R7 = Ur/Uf) and can be interpreted as another marker of elasticity. The Q parameters assist in correlating the elastic and viscous recovery of skin. Q1 represents total recovery and is derived by the elastic recovery area (QE) divided by the maximum recovery area (Q0). Q2 is the viscous recovery and is calculated by the viscous recovery area (QR) divided by Q0 and Q3 is the viscoelastic recovery (Q3 = [QE + QR]/Q0)20 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of Q and R parameters and the equations used to calculate these parameters. Uf represents the total distance the skin stretches after completion of the suction period. Ua represents the total distance the skin retracts back to its normal position at the end of the relaxation period. Ue is the distance skin stretches in the initial 0.1 s of suction. Uv represents the distance the skin stretches between the first 0.1 s and the end of the suction phase. Ur is the distance the skin retracts in the first 0.1 s of the relaxation phase.

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on all curves (curves 1–4) as well as for curves 2–4 in isolation. An unpaired two-tailed t-test was performed between curves 1 and 2, 1 and 3, and 1 and 4, as well as between male and female subjects in all parameters. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were also performed for all parameters between NS and FS after removal of curve 1. GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used to perform statistical analyses. Statistical significance was defined by a value of p < 0.05.

RESULTS

All subjects were healthy men or women between 23 and 35 years of age (median age of 28 years) with no medical comorbidities or preexisting conditions. Raw R-values and Q-values measured in NS for all subjects were recorded and summarized in Table 1. Table 2 provides the raw R and Q-values measured in FS for all subjects. No significant difference existed between sexes in all studied parameters, R0/2/5/6/7 and Q1/2/3, for both NS and FS cohorts. Table 3 provides the comparison between NS and FS for all R and Q-values analyzed in this study. With the data from Table 3, the average standard deviation between all R parameters and Q parameters for NS (0.032 vs. 0.016, p = 0.050) and FS (0.058 vs. 0.041, p = 0.358) show less variance among the area (Q) parameters compared with the point (R) parameters.

Table 1.

Dimensionless parameters for all curves and genders in normal skin

| Curve 1 (mean ± SD) | Curve 2 (mean ± SD) | Curve 3 (mean ± SD) | Curve 4 (mean ± SD) | All curves (mean ± SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0 (Skin pliability) | ||||||

| Male | 1.225 ± 0.183 | 1.317 ± 0.199 | 1.321 ± 0.210 | 1.336 ± 0.210 | 1.307 ± 0.016 | 0.204 |

| Female | 1.228 ± 0.217 | 1.294 ± 0.212 | 1.279 ± 0.221 | 1.289 ± 0.220 | 1.273 ± 0.021 | |

| R2 (Gross elasticity) | ||||||

| Male | 0.865 ± 0.050 | 0.925 ± 0.022 | 0.923 ± 0.029 | 0.924 ± 0.028 | 0.909 ± 0.029 | 0.798 |

| Female | 0.887 ± 0.053 | 0.912 ± 0.038 | 0.910 ± 0.051 | 0.911 ± 0.027 | 0.905 ± 0.012 | |

| R5 (Net elasticity) | ||||||

| Male | 0.918 ± 0.088 | 0.882 ± 0.075 | 0.868 ± 0.069 | 0.869 ± 0.069 | 0.884 ± 0.023 | 0.585 |

| Female | 0.944 ± 0.109 | 0.890 ± 0.076 | 0.879 ± 0.104 | 0.861 ± 0.078 | 0.894 ± 0.036 | |

| R6 (Portion of viscoelasticity) | ||||||

| Male | 0.293 ± 0.099 | 0.155 ± 0.044 | 0.139 ± 0.036 | 0.132 ± 0.034 | 0.180 ± 0.076 | 0.232 |

| Female | 0.334 ± 0.067 | 0.205 ± 0.052 | 0.200 ± 0.066 | 0.186 ± 0.055 | 0.231 ± 0.069 | |

| R7 (Immediate recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.708 ± 0.050 | 0.763 ± 0.045 | 0.761 ± 0.045 | 0.766 ± 0.047 | 0.749 ± 0.028 | 0.123 |

| Female | 0.716 ± 0.098 | 0.735 ± 0.081 | 0.744 ± 0.110 | 0.721 ± 0.090 | 0.729 ± 0.013 | |

| Q1 (Total recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.863 ± 0.050 | 0.925 ± 0.020 | 0.922 ± 0.022 | 0.924 ± 0.022 | 0.908 ± 0.030 | 0.444 |

| Female | 0.881 ± 0.049 | 0.902 ± 0.033 | 0.910 ± 0.042 | 0.900 ± 0.028 | 0.898 ± 0.012 | |

| Q2 (Elastic recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.730 ± 0.049 | 0.785 ± 0.039 | 0.781 ± 0.039 | 0.784 ± 0.040 | 0.770 ± 0.027 | 0.090 |

| Female | 0.733 ± 0.088 | 0.754 ± 0.072 | 0.765 ± 0.091 | 0.740 ± 0.072 | 0.748 ± 0.014 | |

| Q3 (Viscoelastic recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.133 ± 0.024 | 0.140 ± 0.030 | 0.141 ± 0.026 | 0.140 ± 0.032 | 0.138 ± 0.004 | 0.060 |

| Female | 0.148 ± 0.048 | 0.149 ± 0.048 | 0.145 ± 0.055 | 0.160 ± 0.051 | 0.150 ± 0.006 | |

Table 2.

Dimensionless parameters for all curves and genders in fibrotic scars

| Curve 1 (mean ± SD) | Curve 2 (mean ± SD) | Curve 3 (mean ± SD) | Curve 4 (mean ± SD) | All curves (mean ± SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0 (Pliability) | ||||||

| Male | 1.104 ± 0.265 | 1.083 ± 0.301 | 1.149 ± 0.332 | 1.068 ± 0.328 | 1.101 ± 0.039 | 0.070 |

| Female | 0.870 ± 0.272 | 0.944 ± 0.337 | 0.856 ± 0.356 | 0.877 ± 0.354 | 0.886 ± 0.057 | |

| R2 (Gross elasticity) | ||||||

| Male | 0.892 ± 0.073 | 0.961 ± 0.035 | 0.951 ± 0.023 | 0.937 ± 0.048 | 0.935 ± 0.030 | 0.193 |

| Female | 0.754 ± 0.090 | 0.908 ± 0.044 | 0.921 ± 0.027 | 0.910 ± 0.036 | 0.872 ± 0.080 | |

| R5 (Net elasticity) | ||||||

| Male | 0.899 ± 0.160 | 0.993 ± 0.162 | 0.948 ± 0.095 | 0.912 ± 0.059 | 0.938 ± 0.042 | 0.399 |

| Female | 0.921 ± 0.186 | 0.920 ± 0.144 | 0.913 ± 0.125 | 0.921 ± 0.130 | 0.919 ± 0.004 | |

| R6 (Portion of viscoelasticity) | ||||||

| Male | 0.407 ± 0.076 | 0.280 ± 0.089 | 0.237 ± 0.074 | 0.225 ± 0.063 | 0.287 ± 0.083 | 0.422 |

| Female | 0.378 ± 0.089 | 0.209 ± 0.063 | 0.186 ± 0.064 | 0.150 ± 0.038 | 0.231 ± 0.101 | |

| R7 (Immediate recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.643 ± 0.127 | 0.778 ± 0.123 | 0.770 ± 0.106 | 0.746 ± 0.069 | 0.734 ± 0.062 | 0.646 |

| Female | 0.675 ± 0.163 | 0.765 ± 0.140 | 0.773 ± 0.123 | 0.804 ± 0.132 | 0.754 ± 0.055 | |

| Q1 (Total recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.776 ± 0.083 | 0.908 ± 0.047 | 0.907 ± 0.036 | 0.890 ± 0.030 | 0.870 ± 0.064 | 0.733 |

| Female | 0.808 ± 0.101 | 0.901 ± 0.051 | 0.913 ± 0.038 | 0.917 ± 0.046 | 0.885 ± 0.051 | |

| Q2 (Elastic recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.652 ± 0.117 | 0.787 ± 0.110 | 0.776 ± 0.095 | 0.752 ± 0.058 | 0.742 ± 0.061 | 0.693 |

| Female | 0.681 ± 0.148 | 0.770 ± 0.122 | 0.778 ± 0.106 | 0.806 ± 0.116 | 0.759 ± 0.054 | |

| Q3 (Viscoelastic recovery) | ||||||

| Male | 0.123 ± 0.045 | 0.122 ± 0.065 | 0.132 ± 0.061 | 0.138 ± 0.053 | 0.129 ± 0.007 | 0.732 |

| Female | 0.128 ± 0.054 | 0.131 ± 0.076 | 0.135 ± 0.074 | 0.111 ± 0.071 | 0.126 ± 0.010 | |

Table 3.

Direct comparison between normal skin and fibrotic scars for all studied parameters

| Curve 1 (mean ± SD) | Curve 2 (mean ± SD) | Curve 3 (mean ± SD) | Curve 4 (mean ± SD) | All curves (mean ± SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0 (Skin pliability) | ||||||

| NS | 1.384 ± 0.194 | 1.247 ± 0.193 | 1.248 ± 0.202 | 1.253 ± 0.198 | 1.258 ± 0.018 | 0.001 |

| FS | 1.087 ± 0.253 | 0.913 ± 0.318 | 0.952 ± 0.349 | 0.985 ± 0.352 | 0.959 ± 0.352 | |

| R2 (Gross elasticity) | ||||||

| NS | 0.878 ± 0.037 | 0.917 ± 0.019 | 0.915 ± 0.024 | 0.917 ± 0.020 | 0.907 ± 0.019 | 0.081 |

| FS | 0.923 ± 0.084 | 0.834 ± 0.031 | 0.836 ± 0.020 | 0.824 ± 0.024 | 0.854 ± 0.054 | |

| R5 (Net elasticity) | ||||||

| NS | 0.910 ± 0.175 | 0.956 ± 0.140 | 0.930 ± 0.106 | 0.916 ± 0.100 | 0.928 ± 0.020 | 0.012 |

| FS | 0.903 ± 0.070 | 0.876 ± 0.061 | 0.874 ± 0.065 | 0.865 ± 0.061 | 0.880 ± 0.030 | |

| R6 (Portion of viscoelasticity) | ||||||

| NS | 0.311 ± 0.065 | 0.176 ± 0.045 | 0.165 ± 0.049 | 0.155 ± 0.043 | 0.202 ± 0.073 | 0.368 |

| FS | 0.392 ± 0.057 | 0.244 ± 0.058 | 0.212 ± 0.052 | 0.188 ± 0.059 | 0.259 ± 0.092 | |

| R7 (Immediate recovery) | ||||||

| NS | 0.711 ± 0.057 | 0.751 ± 0.056 | 0.754 ± 0.062 | 0.747 ± 0.060 | 0.741 ± 0.020 | 0.904 |

| FS | 0.659 ± 0.152 | 0.772 ± 0.132 | 0.772 ± 0.111 | 0.775 ± 0.112 | 0.744 ± 0.057 | |

| Q1 (Total recovery) | ||||||

| NS | 0.870 ± 0.028 | 0.915 ± 0.020 | 0.917 ± 0.019 | 0.914 ± 0.020 | 0.904 ± 0.022 | 0.033 |

| FS | 0.792 ± 0.096 | 0.805 ± 0.045 | 0.810 ± 0.034 | 0.904 ± 0.038 | 0.848 ± 0.057 | |

| Q2 (Elastic recovery) | ||||||

| NS | 0.731 ± 0.051 | 0.771 ± 0.049 | 0.774 ± 0.053 | 0.765 ± 0.049 | 0.761 ± 0.020 | 0.742 |

| FS | 0.667 ± 0.138 | 0.778 ± 0.116 | 0.777 ± 0.097 | 0.779 ± 0.098 | 0.750 ± 0.056 | |

| Q3 (Viscoelastic recovery) | ||||||

| NS | 0.139 ± 0.032 | 0.144 ± 0.033 | 0.143 ± 0.035 | 0.149 ± 0.033 | 0.144 ± 0.004 | 0.001 |

| FS | 0.126 ± 0.044 | 0.127 ± 0.071 | 0.133 ± 0.064 | 0.124 ± 0.062 | 0.127 ± 0.004 | |

R-value analysis

Analysis of R0, skin pliability/firmness, between curves 2 and 4 was not statistically significant different in both NS and FS (p > 0.99 and p > 0.99, respectively), but inclusion of curve 1 creates a significant difference (***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001, respectively). Differences between curves 1 and 2 (**p < 0.01), curves 1 and 3 (**p < 0.01), and curves 1 and 4 (**p < 0.01) in the NS cohort display how the first curve differed significantly from every other subsequent curve. This same phenomenon is seen in the FS cohort as well (***p < 0.001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01) (Fig. 4A).

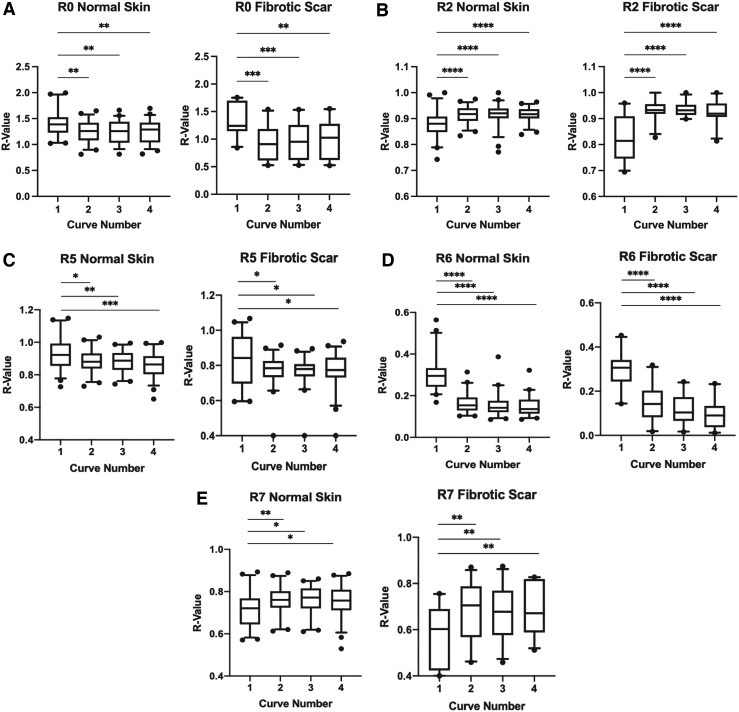

Figure 4.

Individual comparison of curve 1 to curves 2, 3, and 4 within the R0 (A), R2 (B), R5 (C), R6 (D), and R7 (E) parameters in normal skin and FS (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). R-values in the R0, R2, R5, R6, and R7 parameters directly correlate with overall skin elasticity. Higher R-values represent greater overall skin elasticity while lower R-values represent less overall skin elasticity.

Gross elasticity, R2, showed a similarity between curves 2 and 4 in NS (p = 0.93) and FS (p = 0.47), but a significant difference when curve 1 was included in comparison with all other curves (****p < 0.0001 and ****p < 0.0001, respectively). Individual comparison of curve 1 with curves 2–4 were each significantly different in both NS and FS for the R2 parameter (****p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4B).

One-way ANOVA of the R5 (net elasticity) value between curves 2 and 4 was not statistically significant different in both NS and FS (p = 0.45 and p = 0.94, respectively), but, with the addition of curve 1, a significant difference was then seen (****p < 0.0001 and *p < 0.05, respectively). Unpaired t-test between curves 1 and 2 (*p < 0.05), curves 1 and 3 (**p < 0.01), and curves 1 and 4 (***p < 0.001) further demonstrated that the R5 value in the first curve differed significantly from every other subsequent curve in NS. For FS, curve 1 was also significantly different from curves 2, 3, and 4 (*p < 0.05, *p < 0.05, and *p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 4C).

The R6 parameter, which measures a portion of the viscoelasticity, again showed that curves 2–4 were similar in NS (p = 0.23) and FS (p = 0.06), but again significantly different when curve 1 was included in comparison with all other curves (****p < 0.0001 and ****p < 0.0001, respectively). Individual comparison of R6 values in curves 2–4 with curve 1 were each significantly different in both NS and FS (****p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4D).

For immediate recovery, R7, curves 1–4 in NS demonstrated significant differences (*p < 0.05) as well as in FS (**p < 0.01), whereas curves 2–4 were not significantly different in both NS and FS (p = 0.95 and p = 0.97, respectively). Curve 1 compared with curve 2 was significantly different (**p < 0.01), whereas curve 1 compared with curves 3 and 4 were also significantly different (*p < 0.05) in NS. For FS, curve 1 also showed significant differences when matched with curves 2, 3, and 4 (**p < 0.01 for all curves) (Fig. 4E).

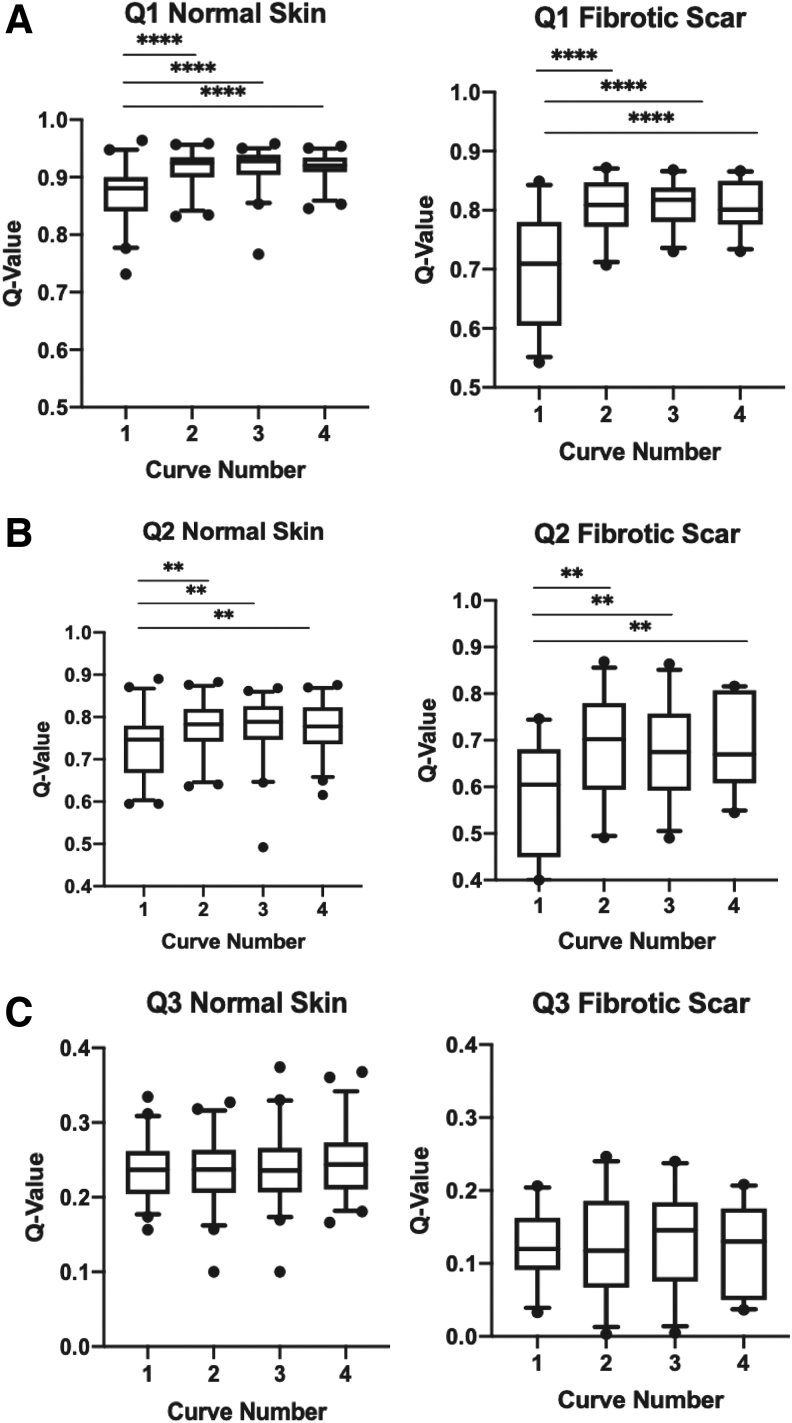

Q-value analysis

Total recovery, represented by Q1, was not significantly different in curves 2–4 for NS and FS (p = 0.99 and p = 0.89, respectively), but, when curve 1 was included, a significant difference appeared (****p < 0.0001 for both NS and FS). Direct individual comparison of curves 2–4 with curve 1 were also all statistically significant in NS and FS (****p < 0.0001 for all curves) (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Individual comparison of curve 1 to curves 2, 3, and 4 within the Q1 (A), Q2 (B), and Q3 (C) parameters in normal skin and FS (**p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001). Q-values in Q1, Q2, and Q3 directly correlate with overall skin recovery as a marker of skin elasticity. Higher Q-values represent greater overall skin recovery/elasticity while lower Q-values represent less skin recovery/elasticity.

Similar to previous parameters, Q2, which represents elastic recovery, had similar curves 2–4 (p = 0.94, p = 0.98, respectively) for NS and FS, but Q2 was significantly different with the addition of curve 1 in both NS (**p < 0.01) and FS (***p < 0.001). Again, when curve 1 was compared individually with curves 2, 3, and 4, all were significantly different in both NS and FS (**p < 0.01 for all curves) (Fig. 5B).

Unlike all the other parameters studied, Q3, a measure of viscoelastic recovery, did not show any differences between curves 1–4 and curves 2–4 for NS (p = 0.78 and p = 0.85, respectively) or FS (p = 0.94 and p = 0.85, respectively). Furthermore, comparison of curve 1 with curves 2–4 individually with an unpaired t-test were also not significantly different for NS (p = 0.60, p = 0.56, and p = 0.29, respectively) or FS (p = 0.99, p = 0.68, p = 0.81, respectively) (Fig. 5C).

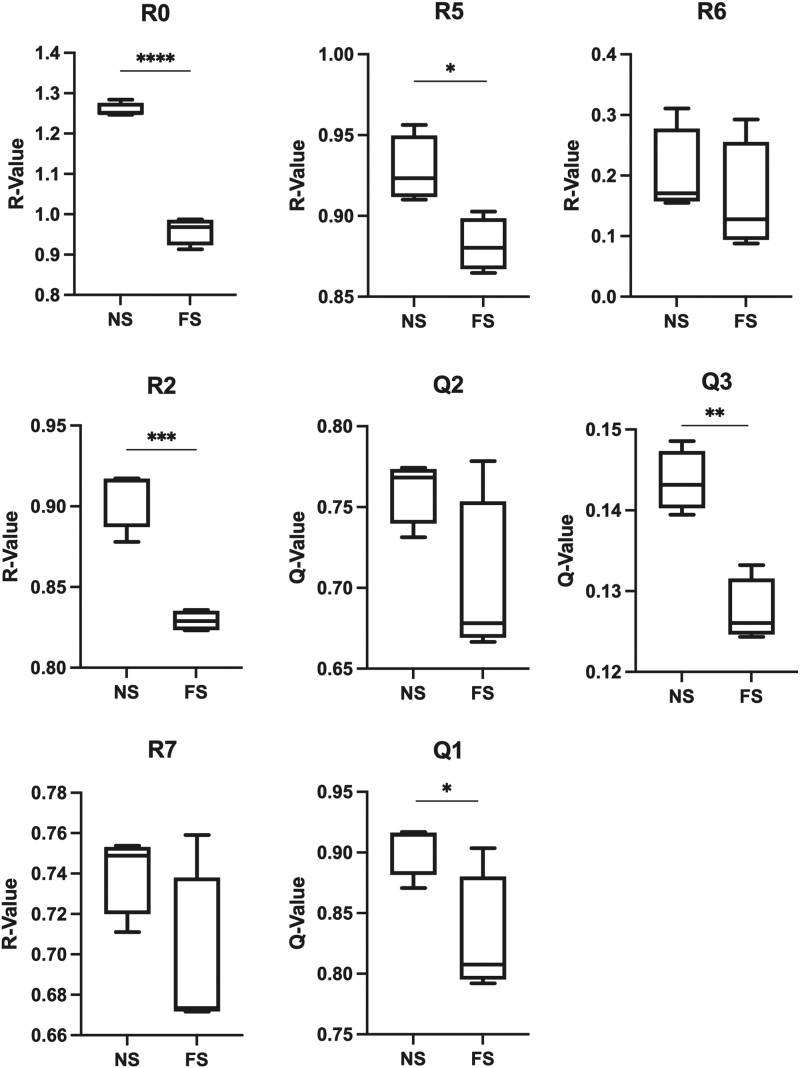

NS versus fibrotic scar analysis

All parameters were compared between FS and analogous NS sites and only R0 demonstrated any significance before removal of curve 1 (***p < 0.001). However, after removal of curve 1, R2, R5, Q1, and Q3 were significantly different between NS and FS cohorts (***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 respectively). R0 also increased in significance after removal of curve 1 (****p < 0.0001). R6 (p = 0.36), R7 (p = 0.90), and Q2 (p = 0.74) were not significantly different between the two cohorts, even after removal of curve 1 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison of FS to analogous sites of normal skin for all parameters (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). The lower R and Q-values in the FS demonstrate how the FS are less elastic and stiffer compared with analogous normal skin sites, most significantly in the R5, Q1, and Q3 parameters.

DISCUSSION

The R0 and R2 measurements are often the most commonly reported parameters in studies employing use of the cutometer; however, this device generates significantly more data that has not been previously utilized because of their lack of validation. Dimensionless parameters that are independent of skin thickness such as R5, R6, R7, Q1, Q2, and Q3 could provide insight into scientific evaluation of skin, and foster better understanding of skin elasticity in vivo. These parameters are considered dimensionless as their mathematical formulas are presented as point ratios (R parameters) or areas (Q parameters) and, thus, are not measured in units of length. Furthermore, these parameters bypass the use of the cross-sectional area of skin that would be needed in other forms of tensile strength testing to determine elasticity such as Young's modulus. In contrast, R1/3/4/8/9 are all dimensional data, which are measured in units of length, and thus hold less utility given the inherent difficulty in standardizing these parameters across a heterogeneous population of subjects. Obtaining accurate, reproducible in vivo skin thickness dimensions can be challenging, especially as the amount of offset during each trial is variable given the amount of force placed on the probe.20 Therefore, as we have demonstrated with our study, eliminating the first curve will allow us to obtain accurate, reproducible data for the parameters R0/2/5/6/7 and Q1/2. The only parameter that did not demonstrate a similar effect after removal of curve 1 is the Q3 parameter. Although not statistically significant with p = 0.06, we believe that the Q3 values between the male and female subjects were significantly different enough that when the conglomerate Q3 data were compiled among all subjects, the differences in gender likely skewed any significant differences that could have been seen in curve 1 compared with curves 2–4.

The difference in measurements between the first curve and the subsequent curves may be owing to a delay in the time required to reach full suction at 300 mbar. This would be an inherent fault in any suction cutometer device as instantaneous achievement of full suction force is ideal, but unrealistic. Although other factors may also impact this first curve anomaly, such as the dynamic viscoelastic properties of human skin or an inadequate seal to create a vacuum between the subject's skin and the probe before suction, our experience using this equipment has led us to believe that these other factors are likely secondary to the delay in achieving the full suction force. Although decreasing the suction force could be of assistance, previous literature and manufacturer recommendations do not use a suction force lower than 300 mbar.

Implementation of our methodology to remove the first curve also decreased the amount of variance between the area (Q) parameters compared with the point (R) parameters as seen when comparing standard deviations. Although not statistically significant when comparing just the standard deviations alone, this difference is directly seen in the parameter values themselves. In addition, the decrease in variance among the Q parameters compared with the R parameters increase the utility of these Q parameters because the point/R parameters represent a single cross-section of skin elasticity in a single moment of time, whereas the area/Q parameters represent skin elasticity over a distinct period of time. The decreased variability in the area/Q parameters is even more pronounced while utilizing our method as the areas under the curve will be more affected vs. the single time point used to calculate any R parameter.

After eliminating the first curve, R5 (net elasticity), Q1 (total recovery), and Q3 (viscoelastic recovery) were also significantly different between NS and FS. These data confirm that, in addition to the previously described and utilized parameters of R0 and R2, the dimensionless parameters of R5, Q1, and Q3 can also reliably be used as markers of skin elasticity. As seen in our data, R5, Q1, and Q3 values for NS were significantly higher than FS. These higher values in NS indicate increased net elasticity and recovery ability compared with FS, meaning that NS is more elastic and less stiff than FS, Clinically, R5 and Q1 may be the most important parameters as they inherently mitigate the effects of creep, the continued deformation of skin after repetitive exposure to a constant load of stress over time.21,22 Creep will mostly affect the viscoelastic measurements of skin as the hydrous components of skin will be altered most by repetitive stress compared with the nonhydrous components of skin.23,24 Owing to the mathematical equations used to calculate R5 and Q1, these viscoelastic shifts are minimized compared with Q3. As R5 is derived from Ur/Ue, it is a representation of the elasticity of the skin within the first 0.1 s of suction and relaxation. These are the times in which skin is closest to its resting physiologic state and poststressed state, respectively, and mitigates the effect of creep as much as possible. The use of R5 and Q1 to diagnose, evaluate, quantify, and monitor skin elasticity in vivo with the suction cutometer has never been demonstrated previously. In addition, despite minimal phenotypic differences between the NS and FS, the cutometer was still able to differentiate elasticity between the two cohorts. If our methodology using the cutometer is effective for well-healed scars, these abilities can also be extrapolated to hypertrophic or hyperfibrotic scars. With these novel findings, we argue to broaden the usable data pool obtained from the suction cutometer to include R5 and Q1 in addition to the previously established parameters of R0 and R2. Using conditions and data to quantify skin elasticity as close as physiologically possible to its native, in vivo state gives clinicians deeper insight into the skin and scars with which they evaluate, diagnose, and treat on a daily basis.

Several limitations exist in this study. The inability to standardize the exact amount of force applied to the probe may skew some of the data as shown in previous studies by Bonaparte et al.15 The site of probe placement can also introduce variability to the data, but given that all subjects in the NS cohort had the probe placed on the same site, this variability was minimized as much as possible.14 Unfortunately, minimizing site variability for the FS cohort was more challenging as the location of scars were distributed across the torso and extremities. Nedelec et al. in 2015 demonstrated the anatomic differences in R0, R2, and R7 parameters in NS using the same suction cutometer device used in our study.25 However, they did not measure the exact same locations we used in our study to measure normal tissue, no analysis of FS was performed, the other dimensionless parameters were not included, and they utilized a different probe size and cutometer software settings from this study. Thus, it would be difficult to directly correlate the two data sets. Nevertheless, their study did demonstrate that there is a difference among different anatomic locations in the body, informing our decision to test analogous NS sites when comparing them with FS. These normal sites would either be NS directly adjacent to the FS in the same anatomic location or analogous sites in the same anatomic location on the contralateral side of the body to mitigate the anatomic site variability. Another limitation of this experiment is that the first curve taken with the probe should be the most accurate measure of true viscoelasticity of skin. The viscoelasticity of human skin considers the water content of skin with the principle of viscosity, the internal resistance to flow when a shearing force or stress is applied to fluid.26 In combination with inherent variables such as proteoglycan composition, extracellular matrix density, and skin thickness, this component of skin is also dependent on a number of external variables such as water consumption, ambient temperature, humidity, core body temperature, hormonal levels, functionality of underlying muscle groups and joints, and the location of the skin.27–30 These dynamics make the cross-sectional data collected with the cutometer regarding the viscoelasticity of skin very difficult to utilize in a significant manner. Therefore, the measurement of precise, reproducible data points pertaining to the relative elasticity of skin either to itself over time or to another location of skin is of greater value than attempting to delineate true viscoelasticity of the selected skin sample at a single point in time.31 Furthermore, investigator and subject movement may influence the contact force and variability of our measurements.32,33 We attempted to mitigate these movements by keeping the subject seated as still as possible for the duration of the experiment and by having the investigator resting their hand on a solid surface while holding the probe to minimize any artifactual motion. Finally, the lack of heterogeneity within our subject population may limit the generalizability of these results, but the ability to demonstrate reliable, precise data on a homogeneous population provides validation of our methodology and allows for future studies with broader subject populations.

In conjunction with the above-mentioned limitations, the main limitation of our study pertains to its lack of clinical translatability. Because a significant amount of debate still exists regarding standardization of scar scales and which scale is best used for incisional scars, we decided against using any other visual scale as a means to clinically validate our study.34–38 We only used the Stony Brook Scar Scale in our inclusion criteria to minimize phenotypic and macroscopic differences between the scars themselves as well as between the fibrotic scar and NS cohorts. If the cutometer could still identify elastic differences between fibrotic skin and NS at a microscopic level, it would logically be able to identify these same differences at a macroscopic level as well. A vast amount of literature has previously demonstrated R0 and R2 with excellent intra- and inter-rater reliability to delineate the elasticity of skin.39–42 Therefore, we decided to compare the remaining dimensionless cutometer parameters to these known parameters of elasticity to first validate our methodology. However, in preventing the introduction of bias and subjectivity by using another scar scale to validate our findings, the amount of data collected regarding phenotypic, structural, and quality differences between the FS and NS is limited. These differences are integral when attempting to discern the amount of fibrosis that occurs in scars clinically. Nevertheless, we first needed to develop and validate a method of reliably collecting and analyzing these dimensionless parameters, and subsequently test this methodology with scars and NS to determine its ability to discriminate between the two before attempting to translate these findings toward direct patient care. The lack of consensus in the medical community relating to scar scale validity and usage drives the need to develop a standard, quantifiable measure of skin elasticity, such as the one used in this study.43,44

CONCLUSION

Precision and reproducibility of data generated by the cutometer has been a key limitation to its widespread implementation in research and clinical use. This study has discovered a method to improve the consistency and accuracy of data gathered by this tool. Furthermore, we probed our methodology's ability to discern differences between NS and FS, and demonstrated significant differences between these states. The clinical utility of this instrument is derived from its ability to measure skin elasticity in vivo in a noninvasive, longitudinal method and the adapted techniques described herein dramatically increase its utility.

KEY FINDINGS

The dimensionless parameters of the suction cutometer (R5, R6, R7, Q1, Q2, and Q3) have been underutilized and overlooked owing to their wide variability.

Elimination of curve 1 generated in each trial of suction cutometer measurements allows for the generation of reproducible and accurate data from these dimensionless parameters.

In a clinical application, R5 and Q1 can best differentiate NS as more elastic than FS.

AUTHORs' CONTRIBUTION

D.B.A., C.V.L., E.J.F., and D.C.W. conceived, designed, and supervised the experiment. D.B.A., C.V.L., E.J.F., performed the experiments and analyzed the data. M.G., N.G., M.K., and K.C. provided resources and formal analysis of data. D.B.A. and D.C.W. wrote the article. D.B.A., C.V.L., E.J.F., A.M., H.P.L., G.C.G. M.T.L., and D.C.W. edited and reviewed the article. All authors have reviewed and approve of the final version of the article.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURES AND GHOSTWRITING

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article. The content of this article was expressly written by the authors and no ghostwriters were used.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSAND FUNDING SOURCES

None. This research was supported by the Center for Dental, Oral, & Craniofacial Tissue & Organ Regeneration (C-DOCTOR grant U24DE026914), NIH grant 1R01DE027346-01A1, PSF/MTF Biologics Allograft Tissue Research Grant, and the Hagey Laboratory for Pediatric Regenerative Medicine.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Darren B. Abbas, MD received his Bachelor of Science with honors in Cellular and Molecular Biology from Tulane University and his Doctor of Medicine from Texas A&M University Health Science Center College of Medicine. He is currently a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Surgery at Stanford University. Arash Momeni, MD is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Surgery at Stanford University, Ryan-Upson Scholar in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Director of Clinical Outcomes Research in the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Stanford University, and the Co-Director of the Hand Transplant Program at Stanford University. Derrick C. Wan, MD is a Professor in the Department of Surgery at Stanford University, member of the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI) at Stanford University, Director of Maxillofacial Surgery at Lucille Packard Children's Hospital, and Hagey Family Faculty Scholar in Pediatric Regenerative Medicine. His research focuses on cellular and molecular mechanisms of wound healing and regeneration, radiation wounds, tissue bioengineering, and developing novel biotherapeutics.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- FS

fibrotic scar

- NS

normal skin

REFERENCES

- 1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marshall CD, Hu MS, Leavitt T, Barnes LA, Lorenz HP, Longaker MT. Cutaneous scarring: basic science, current treatments, and future directions. Adv Wound Care 2016;7:29–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marcenaro M, Sacco S, Pentimalli S, et al. Measures of late effects in conservative treatment of breast cancer with standard or hypofractionated radiotherapy. Tumori 2004;90:586–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nazzal M, Osman MF, Albeshri H, Abbas DB, Angel CA. Wound Healing. In: Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, et al., eds. Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. 11th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=1164307640 (last accessed June 10, 2021).

- 5. Fahy EJ, Griffin M, Lavin C, Abbas D, Longaker MT, Wan D. The adrenergic system in plastic and reconstructive surgery: physiology and clinical considerations. Ann Plast Surg 2021 [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilkes GL, Brown IA, Wildnauer RH. The biomechanical properties of skin. CRC Crit Rev Bioeng 1973;1:453–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Draaijers LJ, Botman YAM, Tempelman FRH, Kreis RW, Middelkoop E, van Zuijlen PPM. Skin elasticity meter or subjective evaluation in scars: a reliability assessment. Burns 2004;30:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee KC, Bamford A, Gardiner F, et al. Investigating the intra- and inter-rater reliability of a panel of subjective and objective burn scar measurement tools. Burns 2019;45:1311–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Busche MN, Thraen A-CJ, Gohritz A, Rennekampff H-O, Vogt PM. Burn Scar Evaluation Using the Cutometer® MPA 580 in Comparison to “Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale” and “Vancouver Scar Scale.” J Burn Care Res 2018;39:516–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Müller B, Elrod J, Pensalfini M, et al. A novel ultra-light suction device for mechanical characterization of skin. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nedelec B, Correa JA, Rachelska G, Armour A, LaSalle L. Quantitative measurement of hypertrophic scar: interrater reliability and concurrent validity. J Burn Care Res 2008;29:501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nedelec B, Correa JA, Rachelska G, Armour A, LaSalle L. Quantitative measurement of hypertrophic scar: intrarater reliability, sensitivity, and specificity. J Burn Care Res 2008;29:489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Enomoto DNH, Mekkes JR, Bossuyt PMM, Hoekzema R, Bos JD. Quantification of cutaneous sclerosis with a skin elasticity meter in patients with generalized scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35:381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bonaparte JP, Chung J. The effect of probe placement on inter-trial variability when using the Cutometer MPA 580. J Med Eng Technol 2014;38:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonaparte JP, Ellis D, Chung J. The effect of probe to skin contact force on Cutometer MPA 580 measurements. J Med Eng Technol 2013;37:208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mascharak S, desJardins-Park HE, Davitt MF, et al. Preventing Engrailed-1 activation in fibroblasts yields wound regeneration without scarring. Science 2021;372:eaba2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shen AH, Borrelli MR, Adem S, et al. Prophylactic treatment with transdermal deferoxamine mitigates radiation-induced skin fibrosis. Sci Rep 2020;10:12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18. Borrelli MR, Deleon NMD, Adem S, et al. Grafted Fat Depletes the Profibrotic Engrailed-1-Positive Fibroblast Subpopulation and Ameliorates Radiation-Induced Scalp Fibrosis. J Am Coll Surg 2020;231:E186. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chin CJ, Franklin JH, Turner B, et al. A novel tool for the objective measurement of neck fibrosis: validation in clinical practice. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;41:320–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klosová H, Štětinský J, Bryjová I, Hledík S, Klein L. Objective evaluation of the effect of autologous platelet concentrate on post-operative scarring in deep burns. Burns 2013;39:1263–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Langton AK, Graham HK, Griffiths CEM, Watson REB. Ageing significantly impacts the biomechanical function and structural composition of skin. Exp Dermatol 2019;28:981–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilhelmi BJ, Blackwell SJ, Mancoll JS, Phillips LG. Creep vs. stretch: a review of the viscoelastic properties of skin. Ann Plast Surg 1998;41:215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thornton GM, Leask GP, Shrive NG, Frank CB. Early medial collateral ligament scars have inferior creep behaviour. J Orthop Res 2000;18:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scott PG, Dodd CM, Tredget EE, Ghahary A, Rahemtulla F. Chemical characterization and quantification of proteoglycans in human post-burn hypertrophic and mature scars. Clin Sci 1996;90:417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nedelec B, Forget NJ, Hurtubise T, et al. Skin characteristics: normative data for elasticity, erythema, melanin, and thickness at 16 different anatomical locations. Skin Res Technol 2016;22:263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Everett JS, Sommers MS. Skin viscoelasticity: physiologic mechanisms, measurement issues, and application to nursing science. Biol Res Nurs 2013;15:338–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kang MJ, Kim B, Hwang S, Yoo HH. Experimentally derived viscoelastic properties of human skin and muscle in vitro. Med Eng Phys 2018;61:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu F, Lu T. Introduction to Skin Biothermomechanics and Thermal Pain. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ohno H, Nishimura N, Yamada K, et al. Effects of water nanodroplets on skin moisture and viscoelasticity during air-conditioning. Skin Res Technol 2013;19:375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joodaki H, Panzer MB. Skin mechanical properties and modeling: a review. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 2018;232:323–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dobrev H. Novel ideas: the increased skin viscoelasticity - a possible new fifth sign for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2013;9:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Müller B, Ruby L, Jordan S, Rominger MB, Mazza E, Distler O. Validation of the suction device Nimble for the assessment of skin fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nikkels-Tassoudji N, Henry F, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Computerized evaluation of skin stiffening in scleroderma. Eur J Clin Invest 1996;26:457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kantor J. Relative benefits of the SCAR scale compared with the patient and observer scar assessment scale for postreconstructive surgery photographic scar assessment rating. Dermatol Surg 2021;47:728–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thompson CM, Sood RF, Honari S, Carrougher GJ, Gibran NS. What score on the Vancouver Scar Scale constitutes a hypertrophic scar? Results from a survey of North American burn-care providers. Burns 2015;41:1442–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quinn JV, Wells GA. An assessment of clinical wound evaluation scales. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:583–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chung J-H, Kwon S-H, Kim K-J, et al. Reliability of the patient and observer scar assessment scale in evaluating linear scars after thyroidectomy. Adv Skin Wound Care 2021;34:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hallam MJ, McNaught K, Thomas AN, Nduka C. A practical and objective approach to scar colour assessment. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2013;66:e271–e276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jang SI, Kim EJ, Park H, et al. A quantitative evaluation method using processed optical images and analysis of age-dependent changes on nasolabial lines. Skin Res Technol 2015;21:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Woo MS, Moon KJ, Jung HY, et al. Comparison of skin elasticity test results from the Ballistometer® and Cutometer®. Skin Res Technol 2014;20:422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee KC, Bamford A, Gardiner F, et al. Burns objective scar scale (BOSS): validation of an objective measurement devices based burn scar scale panel. Burns 2020;46:110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kawałkiewicz W, Matthews-Kozanecka M, Janus-Kubiak M, Kubisz L, Hojan-Jezierska D. Instrumental diagnosis of facial skin—A necessity or a pretreatment recommendation in esthetic medicine. J Cosmet Dermatol 2021;20:875–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Price K, Moiemen N, Nice L, Mathers J. Patient experience of scar assessment and the use of scar assessment tools during burns rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Burns Trauma 2021;9:tkab005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bae SH, Bae YC. Analysis of frequency of use of different scar assessment scales based on the scar condition and treatment method. Arch Plast Surg 2014;41:111–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]