Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with protean manifestations that predominantly affects young women. Certain ethnic groups are more vulnerable than others to developing SLE and experience increased morbidity and mortality. Reports of the global incidence and prevalence of SLE vary widely, owing to inherent variation in population demographics, environmental exposures and socioeconomic factors. Differences in study design and case definitions also contribute to inconsistent reporting. Very little is known about the incidence of SLE in Africa and Australasia. Identifying and remediating such gaps in epidemiology is critical to understanding the global burden of SLE and improving patient outcomes. Mortality from SLE is still two to three times higher than that of the general population. Internationally, the frequent causes of death for patients with SLE include infection and cardiovascular disease. Even without new therapies, mortality can potentially be mitigated with enhanced quality of care. This Review focuses primarily on the past 5 years of global epidemiological studies and discusses the regional incidence and prevalence of SLE and top causes of mortality.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease with heterogeneous clinical manifestations ranging from mild cutaneous disease to catastrophic organ failure and obstetrical complications. Young women are disproportionately affected by SLE, with a greater prevalence and incidence of this disease in certain ethnic populations such as Black, Asian and Hispanic populations1,2.

Reports from the past 5 years on the incidence and prevalence of SLE have shown considerable variation across global regions and even within subpopulations3–5. These differences are probably attributable to true variation, but also to differences in study design and case definition.

Unfortunately, SLE is one of the leading causes of death in young women6. In a meta-analysis of >26,000 female patients with SLE in the USA, the all-cause mortality was 2.6-f old higher than that of the general population, with a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) of more than 2 for cardiovascular disease and SMRs of almost 5 for infection and renal disease7.

In this Review, we focus on studies that have been published in the past 5 years on SLE epidemiology, and provide an update on the incidence, prevalence and mortality rates of SLE while discussing the leading causes of death in major global geographic regions. We include older studies from regions with very limited data, such as Africa and Australia. We discuss frequent causes of death across international regions that are potentially remediable through improved quality of care8, and the factors that contribute the most to unfavourable outcomes in each region, such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status. An updated understanding of the international burden of SLE is needed to enable us to allocate resources and address health disparities.

Epidemiology by geographic region

North America

Incidence and prevalence.

Estimates of the number of cases of SLE in North America vary widely, with the reported overall incidence ranging between 3.7 per 100,000 person- years and 49 per 100,000 in the US Medicare population9,10 and the prevalence ranging from 48 to 366.6 per 100,000 individuals9,11. In the past few years, data from incidence and prevalence studies from 1946 to 2016 have been comprehensively reviewed3–5. Epidemiological efforts conducted in North America from 2015 to 2020 are summarized in TABLE 1 and TABLE 2, and further details are available in Supplementary Information Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 |.

International incidence and prevalence of SLE by geographic region

| Region | Study description | Ethnicity and sex (%) | Incidence (cases per 100,000 person- years unless otherwise specified) | Prevalence (cases per 100,000 persons unless otherwise specified) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | |||||

| Southeastern Michigan, USA | Population survey (2002–2005); used the ACR 1997 criteria | Arab or Chaldean American (2); non- Arab, non- Chaldean, white (39); non- Arab, non- Chaldean Black (59); female (91.1); male (8.9) | Arab or Chaldean American: 7.6; non- Arab, non- Chaldean, white: 3.7; non-A rab, non- Chaldean, Black: 8.8 | Arab or Chaldean American: 62.6; non-A rab, non- Chaldean, white: 52.3; non- Arab, non- Chaldean, Black: 120.1 | 16 |

| San Francisco County, CA, USA | Population survey (2007–2009); used ACR 1997 criteria or an alternative definition of SLE (three ACR criteria plus a documented diagnosis of SLE or related renal disease) | Black (20); white (37); Asian or Pacific Islander (37); Hispanic (15); female (88.9); male (11.1) | Overall: 4.6; Black: 15.5; white: 2.8; Asian or Pacific Islander: 4.1; Hispanic: 4.2 | Overall: 84.8; Black: 241.0; white: 55.2; Asian or Pacific Islander: 90.5; Hispanic: 94.7 | 1 |

| Manhattan, NY, USA | Population survey (2007–2009), using the ACR 1997 criteria, SLICC 2012 criteria or treating rheumatologist’s diagnosis | Non- Hispanic white (28); non- Hispanic Black (26); Hispanic (32); non- Hispanic Asian (10); non- Hispanic other (3); female (90.6); male (9.4) | Overall: 6.0; non- Hispanic white: 5.6; non-H ispanic Black: 10.1; Hispanic: 4.1; non- Hispanic Asian: 5.4 | Overall: 75.9; non- Hispanic white: 51.4; non-H ispanic Black: 133.1; Hispanic: 84.6; non- Hispanic Asian: 75.5 | 2 |

| Olmsted County, MN, USA | Medical record review (1993–2005); used the ACR 1997 or SLICC 2012 criteria | White (84); Black (7); Asian (5); Native American (2); female (93.2); male (6.8) | ACR 1997: 3.7; SLICC 2012: 4.9 | NR | 10 |

| Alberta, Canada | Administrative database analysis (2000–2015); used ICD codes | Ethnicity NR; female (85.8); male (14.2) | Overall: 4.4 per 100,000 population; male: 1.3 per 100,000 population; female: 7.7 per 100,000 population | Overall (year 2000): 48; male (year 2000): 13.5; female (year 2000): 83.2; overall (year 2015: 90; male (year 2015): 25.5; female (year 2015): 156.7 | 11 |

| USA | Cross- sectional analysis (2009–2016); used ICD codes | White (87); Black (7); Asian (2); Hispanic (1); other (3); female (88.0); male (12.0) | Overall (year 2009): 46.9 per 100,000 in the US Medicare population; overall (year 2016): 49.0 per 100,000 in the US Medicare population | Overall (year 2009): 301.1; overall (year 2016): 366.6 | 9 |

| Europe | |||||

| France | Cross- sectional registry analysis (2010); used ICD codes | French population: ethnicity NR; female (86.7); male (13.3) | Overall: 3.3; female: 5.5; male: 0.9 | Overall: 47.0; female: 79.1; male: 11.8 | 28 |

| Sweden | Cross- sectional registry analysis (2010); used ICD codes, physician visits and prescription records | Swedish population: ethnicity NR; female (81–87); male (13–19) | NR | Overalla: 46–85; femalea: 79–144; malea: 12–25 | 29 |

| Val Trompia, Italy | Analysis of data from hospital, general practitioner and laboratory records (2009–2012); used the ACR 1982 criteria | Val Trompia region, defined in northern Italy: ethnicity NR; female (89); male (11) | Overall: 2.0 | Overall (year 2012): 39.2; female: 68.8; male: 9.0 | 32 |

| Germany | Cross sectional registry analysis (2002); used ICD codes | German: ethnicity NR; female (80); male (20) | Female: 1.9; male: 0.9 | 36.7 | 24 |

| Southern Sweden | Longitudinal prospective study (1994–2006); potential cases retrieved using ICD codes and ANA testing, and the diagnosis was confirmed through medical file review using Fries & Holman’s criteria110, and thereafter classified using the ACR 1982 criteria | Residents within a defined region in Southern Sweden: female (85); male (15) | 2.8 | Point prevalence (year 2006): 65 | 31 |

| UK | Longitudinal registry- based study (1999–2012); used Read codes | Ethnicity information available for 61.9% of the study population, distributed as below: white (44.9); Indian (0.8); Black African (0.7); Pakistani (0.6); Black Caribbean (0.4); Chinese (0.2); Bangladeshi (0.2); other/unclassified/mixed (50.3); female (86); male (14) | Overall: 4.9; female: 8.3; male: 1.4 | Point prevalence; overall (year 2012): 97.0; in the subgroup where ethnicity was available: white: 134.5; Indian: 193.1; Black African: 179.8; Pakistani: 142.8; Black Caribbean: 517.5; Chinese: 188.4; Bangladeshi: 80.3 | 27 |

| Crete, Greece | Community- based registry analysis that retrieved cases from multiple sources (1999–2013); used ACR 1997 or SLICC 2012 criteria | Greek, residents of Crete: ethnicity NR; female (92.3); male (7.7) | Overall: 7.4 | Point prevalence (year 2013): 123.4 | 30 |

| Denmark | Longitudinal analysis of the National Patient Registry (1995–2011); used ICD codes | Danish population: ethnicity NR; female (86); male (14) | Overall: 2.3; female: 4.0; male: 0.7 | Point prevalence (year 2011): 45.2 | 25 |

| Estonia | Registry-b ased study (2006–2010); cases retrieved using ICD codes and a medical file review and the diagnosis verified using the ACR 1982 criteria | Estonian population: ethnicity NR; female (89.7); male (10.3) | Intervalb: 1.5–1.8 | Intervalb: 37–40 | 34 |

| Malta | Cross- sectional cohort analysis (2012–2016); used the SLICC 2012 criteria | White (97.2); Asian (0.3); female (93.5); male (6.5) | 1.5 | 29.3 | 33 |

| Spain | Questionnaire- based cross- sectional analysis (2016–2017); diagnosis confirmed by a medical file review and, if needed, a medical visit | Spanish population: ethnicity NR; female (83); male (17) | NR | 210 | 35 |

| Hungary | Registry based study (2008–2017); used ICD codes | Hungarian population: ethnicity NR; female (85); male (15) | Year (2008–2017): 4.9; year (2016): 3.8 | Year (1999): 36.1; year (2016): 70.5 | 26 |

| South America | |||||

| Argentina | Study based on a single private healthcare organization that serves 5–7% of the population (1998–2009); used the ACR 1997 criteria | Predominantly white; female (83.8); male (16.2) | 6.3 | 58.6 | 48 |

| State of Monagas, Venezuela | Cross- sectional study; used COPCORD methodology | NR | NR | 0.07 cases per 100 screened individuals | 50 |

| Cuenca City, Ecuador | Cross- sectional study; used COPCORD methodology | NR | NR | 0.06 cases per 100 screened individuals | 51 |

| Rosario City, Argentina | Cross- sectional study; used COPCORD methodology | Qom indigenous (100) | NR | 0.06 cases per 100 screened individuals | 52 |

| Colombia | Nationwide database analysis (2012–2016); used ICD codes | Ethnicity NR; female (89); male (11) | NR | Overall (crude): 91.9; individuals aged ≥18 years (crude): 126.3; female (adjustedc): 204.3; male (adjustedc): 20.2 | 49 |

| Colombia | Incidence rates were calculated by applying the illness-d eath model, using age- specific prevalence data (2012–2016) from Fernández-A vila et al.49, the overall Colombia mortality from the World Health Organization111 and hazard ratio trends for SLE adapted from Bernatsky et al.112 | NR | Females (aged 30–39 years): 20; females (aged 45 years): 1; males (aged 20–29 years): 2.5; males (aged ≥75 years): 2.8 | NR | 47 |

| Tucumán State, Argentina | Hospital and clinical record review (2005–2012); used the ACR 1997 criteria | Mestizo (83); female (93.5); male (6.5) | Year 2007: 1.4; year 2012: 4.2 | 34.9 | 46 |

| Asia | |||||

| Taiwan | Retrospective cohort study (2000–2007); used ICD codes | Taiwan Chinese: female (88); male (12) | Average incidence (years 2000–2007): 8.1 | Average prevalence (years 2000–2007): 55.6 | 57 |

| Taiwan | Population- based cohort study (2003–2008); used ICD codes | Taiwan Chinese: female (87.4); male (12.6) | 4.9 | 97.5 | 61 |

| Korea | Retrospective cohort study (2006–2010); used the ACR 1997 criteria | Korean: female (85.6); male (14.4) | Year 2008: 2.5; year 2009: 2.8 | Year 2006: 20.6; year 2007: 21.9; year 2008: 23.5; year 2009: 24.9; year 2010: 26.5 | 58 |

| China | Population- based case–control study (2009–2010); used the ACR 1997 criteria | Mainland Chinese: female (91.3); male (8.7) | NR | 37.6 | 60 |

| United Arab Emirates | Retrospective cohort study (2009–2012), using ACR (version not specified or SLICC 2012 criteria | Native Arabian (100); female (81.3); male (18.7) | 8.6 | 103 | 59 |

| Australasia | |||||

| New Zealand | Retrospective cohort study and medical records review (1975–1981); used the Fries & Holman criteria110 | White (71); Polynesian (25); other (4); female (90); male (10) | NR | Overall (Auckland): 18; Polynesian women: 99 | 81 |

| Australia | Retrospective cohort study and hospital and physician medical records review (1984–1991); used the ACR 1982 criteria | Indigenous Australian (100); female (95) | 11 | Overall: 52; female: 100 | 77 |

| Australia | Retrospective cohort study and physician medical records review (1993–1995); used the ACR 1982 criteria | Indigenous Australian (100) | NR | Sydney: 13; North Queensland: 89 | 79 |

| Australia | Retrospective cohort study and physician medical records review (1996–1998); used the ACR 1982 criteria | White (73); Indigenous Australian (24); other (3); female (86); male (14) | NR | Overall: 45.3; Indigenous Australian: 92.8 | 80 |

| Australia | Retrospective study and medical records review (1990–1999); used the ACR 1997 criteria | White (25); Indigenous Australian (75); female (83); male (17) | NR | White: 19; Indigenous Australian: 73 | 78 |

| Africa | |||||

| Nairobi, Kenya | Cross- sectional study of a rheumatology clinic (2010–2011); used the ACR 1982 or ACR 1997 criteria | Black African (100); female (100) | NR | Overall: 3,299.5 | 93 |

| Douala, Cameroon | Cross- sectional study of hospitalized patients in an internal medicine unit (1999–2009); used the ACR 1982 criteria | Black African (100); female (92.3); male (7.7) | NR | Overall: 601.3 | 91 |

| Port Harcourt, Nigeria | Cross- sectional study of patients at a rheumatology and dermatology clinic (2012–2013); used the SLICC 2012 criteria | Black African (100) | NR | Overall: 2,900.1 | 92 |

| Nairobi, Kenya | Cross- sectional study of an arthritis clinic (2002–2013); used the SLICC 2012 criteria | Black African (100); female (97); male (3) | NR | Overall: 1,002.5 | 95 |

| Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire | Cross- sectional study of a rheumatology clinic (1987–2014); used the ACR 1982 criteria | Black African (100); female (98.3); male (1.7) | NR | Overall: 647.3 | 94 |

| Dakar, Senegal | Cross- sectional study of hospitalized patients in an internal medicine unit (2005–2014); used the ACR 1982 criteria | Black African (100); female (94.5); male (5.5) | NR | Overall: 7, 713.5 | 96 |

| Kampala, Uganda | Cross- sectional study of patients at a rheumatology clinic (2014–2019); used the ACR 1997, SLICC 2012 or EULAR–ACR 2019 criteria | Black African (100); female (91.1); male (8.9) | NR | Overall: 5,495.6 | 90 |

Refer to Supplementary Table 1 for further details. ANA, antinuclear antibody; COPCORD, Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Diseases; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NR, not reported; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLICC, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus International Collaborating Clinics.

Higher number refers to cases that required just one ICD coded visit, whereas the lower number refers to cases that required several visits or supporting information.

Lower number refers to validated cases only, whereas higher number also includes cases with only one ICD code that have not been validated.

Adjusted to the 2014 WHO world population.

Table 2 |.

Mortality in SLE by geographic region

| Region | Study description | Ethnicity (%) | Number of patients and/or deaths | Mortality (standardized mortality ratio if not otherwise specified) | Frequent causes of death (% if not otherwise specified) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | ||||||

| USA | Review of billing claims (2000–2006); used ICD codes | Black (40); white (38); Hispanic (15); Asian (4); American Indian (2) | Patients with SLE: 42,221 | Crude annual mortality, per 1,000 person-y ears; overall: 19.1; Black: 24.1; white: 20.2; Hispanic: 7.1; Asian: 5.2; American Indian: 27.5 | NR | 20 |

| USA | Death certificate analysis (1968–2013); used ICD codes | Black (31); white (65); Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan Native (4) | SLE- related deaths: 50,249; other deaths (non- SLE related): 100,851,288 | Age- standardized mortality (year 2013), per 100,000 persons; overall: 0.34; male: 0.10; female: 0.55; Black: 0.85; white: 0.26; Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan Native: 0.24 | NR | 17 |

| Fulton and DeKalb Counties, GA, USA | Incident and prevalent SLE cases from the Georgia Lupus Registry were matched to the National Death Index (2002–2016); used ACR 1997 criteria or an alternative definition of SLE (one of three ACR criteria plus a diagnosis of SLE by a rheumatologist) | Black (77); white (23) | Overall: 400 deaths (out of 1,335 patients with SLE); male: 51 deaths; female: 349 deaths; Black: 324 deaths; white: 76 deaths | Overall: 3.1; male: 3.0; female: 3.1; Black: 3.3; white: 2.4 | NR | 18 |

| Europe | ||||||

| UK | Longitudinal prospective study of an inception cohort (1989–2010); used the ACR 1997 criteria | White (51.6); African Caribbean (20.7); South Asian (22); Chinese (2.4) | 37 deaths (out of 382 patients with SLE) | 2.0 | Infection (37.8); cardiovascular disease (27); malignancy (13.5) | 41 |

| UK | Cohort study; used ACR 1982 criteria | White (60); Black (35); Asian (10) | 76 deaths (out of 511 patients with SLE) | 3.1 | NR | 36 |

| UK | Retrospective registry- based cohort study (1998–2012), using Read codes | Multi- ethnic UK population: ethnicity NR | 227 deaths (out of 2,740 patients with SLE) | Mortality rate ratio: overall: 1.7; female: 1.6; male: 1.8 | Cardiovascular disease (33); malignancy (25) | 40 |

| Italy | Single- centre long- term cohort study (1972–2014); used the ACR 1997 criteria | Italian: ethnicity NR | 36 deaths (out of 511 patients with SLE) | NR | Malignancy (33.3); organ failure (22.2); cardiovascular disease (16.7) | 42 |

| UK | Population- based matched control cohort study (1999–2014); used Read codes | Multi- ethnic UK population: ethnicity NR | Years 1996–2006: 76 deaths (out of 1,470 patients with SLE); years 2007–2014: 76 deaths (out of 1,666 patients with SLE) | Hazard ratio: years 1996–2006: 2.1; years 2007–2014: 2.1 | NR | 38 |

| Croatia | Medical file review (2002–2011); used ACR 1982 or ACR 1997 criteria | Croatian: ethnicity NR | 90 deaths | NR | Cardiovascular disease (40); infection (33); SLE (29); malignancy (17) | 45 |

| Southern Sweden | Longitudinal study of inception cohort (patients recruited 1981–2006 and followed until 2014); used Fries & Holman110 criteria | Predominantly white: ethnicity NR | 60 deaths (out of 175 patients with SLE) | Overall: 2.5; female: 2.7; male: 1.9 | Cardiovascular disease (51.7); infection (15.0); malignancy (13.3); SLE (6.7) | 37 |

| Norway | Population- based cohort study (patients recruited 1999–2008 and followed until 2014); used ACR 1997 criteria | Non- European origin (16); European (84%) | 56 deaths (out of 325 patients with SLE) | Overall: 2.1; patients with lupus nephritis: 3.8; patients without lupus nephritis: 1.7 | NR | 44 |

| Hungary Registry- based study (2008–2017); used ICD codes | Total population of Hungary: ethnicity NR | 481 deaths (out of 4,503 patients with SLE) | 1.6 | Cardiovascular disease (47); infection (43); malignancy (18) | 26 | |

| UK Registry- based, prospective, population- based cohort study (1987–2012); used Read codes | 8% of British population: ethnicity NR | 442 deaths (out of 4,358 patients with SLE) | 1.8 | Hazard ratio versus 6 matched controls per case: accident and suicide (4.3); infection (3.2); cardiovascular disease (2.5); malignancy (1.4) | 39 | |

| South America | ||||||

| Brazil | Ecological study of deaths attributed to SLE using administrative data (2002–2011) | NR | 8,761 deaths | 4.76 deaths per 1,000,000 inhabitants | SLE (77); cardiovascular disease (6); infection (2.8); respiratory condition (2.2); gastrointestinal condition (2.1); genitourinary condition (1.9) | 53 |

| Tucuman state, Argentina | Retrospective cohort study (2005–2012) | NR | 32 deaths (out of 353 patients with SLE) | 9.1% | Infection (43.8) | 46 |

| Asia | ||||||

| Saudi Arabia | Retrospective cohort study (2001–2009); used; ARA criteria113 | Middle Eastern population: ethnicity NR | 8 deaths (out of 99 patients with SLE) | 8.2% | Sepsis (62.5); ischaemic heart disease (12.5); pulmonary embolism (12.5) | 62 |

| China | Retrospective multi- centre cohort study (1999–2009); used ACR 1982 or ACR 1997 criteria | Mainland Chinese | 166 deaths (out of 1,956 patients with SLE) | 8.5% | Infection (25.9); renal failure (19.3); neuropsychiatric lupus (18.7) | 67 |

| Thailand | Retrospective multi- centre study (1996–2005); used ACR 1982 criteria | Thai | 66 deaths (out of 749 patients with SLE) | Overall: 1.2 deaths per 100 person- years | Active disease and infection (40.9); infection (31.8); active disease (9.1); intracranial haemorrhage (3); renal failure (3); upper gastrointestinal bleeding (1.5) | 66 |

| Hong Kong | Prospective cohort study (1995–2011); used ACR 1997 criteria | Hong Kong Chinese | 694 patients with SLE; number of deaths NR | Overall: 4.8; patients with lupus nephritis: 9.0; patients with end- stage renal damage: 14 | Infection NR | 72 |

| Taiwan | Retrospective cohort study (1996–2009); used ICD codes | Predominantly Han Chinese (>98) | 4,353 patients with SLE; number of deaths NR | Overall: hazard ratio 2.2 | NR | 63 |

| Japan | Retrospective cohort study (1984–2010); used ACR 1997 criteria | Japanese (100) | 14 deaths (out of 186 patients with SLE) | 3.6 | Infection (50); suicide (14); acute myocardial infarction (14); stroke (7) | 68 |

| Taiwan | Population- based cohort study (2003–2008); used ICD-9 codes | Taiwan Chinese | 1,611 deaths (out of 6,675 patients with SLE) | 11.1 | NR | 61 |

| China | Multi- centre nationwide cohort study (2005–2014); used ACR 1982 or ACR 1997 criteria | Mainland Chinese | 360 deaths (out of 29,510 patients with SLE) | 2.1 | Infection (65.8); lupus nephritis (48.6); haematological abnormality (18.1); neuropsychiatric lupus (15.8); interstitial lung disease (13.1) | 73 |

| Australasia | ||||||

| New Zealand | Retrospective chart review (1975–1980); used ACR 1982 criteria | White (71); polynesian (25); other (4) | 15 deaths (out of 151 patients with SLE) | 2.5–12 deaths per 1,000,000 person years | NR | 81 |

| Australia | Retrospective chart review (1984–1991); used ACR 1982 criteria | Indigenous Australian (100) | deaths (out of 22 patients with SLE) | NR | Active SLE including septic complications (78); cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction) (22) | 77 |

| Australia | Retrospective chart review (1996–1998); used ACR 1982 criteria | White (73); Indigenous Australian (24); other (3) | deaths (out of 108 patients with SLE) | NR | Cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism or stroke) (67); active SLE (vasculitis, cardiomyopathy) and septic complications (33) | 80 |

| Africa | ||||||

| South Africa | Retrospective chart review of patients with lupus nephritis attending a hospital (1995–2009); used ACR 1982 criteria | Black African (16.7); Asian (4.5); multiracial (77.3); white (1.5) | deaths (out of patients with SLE) | NR | Sepsis and/or renal failure (61.5); cardiac failure (15.4); gastrointestinal haemorrhage (3.8); acute pancreatitis (3.8); cerebral vasculitis (3.8); unknown (11.5) | 97 |

| Kenya | Cross- sectional study of a rheumatology clinic (2010–2011); used ACR or ACR 1997 criteria | Black African (100) | deaths (out of patients with SLE) | NR | NR | 93 |

| Cameroon | Cross- sectional study of hospitalized patients in an internal medicine unit (1999–2009); used ACR criteria | Black African (100) | deaths (out of patients with SLE) | NR | Neurological involvement (50.0); dialysis- related sepsis (50.0) | 91 |

| South Africa | Review of hospitalizations at a tertiary referral hospital (2003–2009); used ACR 1982 or ACR criteria | Black African (33.5); Indian (59.3); multiracial (5.4); white (1.8) | deaths (out of patients with SLE) | NR | Infection (62.5); sudden cardiorespiratory event (20.8); neurological event (8.3); renal failure (4.2); bullous lupus erythematous (4.2) | 99 |

| South Africa | Retrospective chart review of patients with SLE at a tertiary care university hospital (2003–2012); used ACR criteria | Black African (33.6); Indian (58.1); multiracial (4.2); white (4.2) | deaths (out of patients with SLE) | NR | Infection (49.1); cardiorespiratory event (24.5); neurological event (11.3); malignancy (5.7); renal failure (5.7); unknown (3.8) | 98 |

| Ghana | Review of hospitalizations in a teaching hospital (2007–2009); used ACR criteria | Black African (100) | deaths (out of patients with SLE) | NR | Infections and complications NR | 100 |

Refer to Supplementary Table 2 for further details. ARA, American Rheumatism Association; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NR, not reported; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Historically, researchers have estimated the burden of SLE in the USA using several different methods of case identification, including death registries, clinic and hospital records and claims- based databases that are reliant on International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes12. To better capture the extent of the burden of SLE, particularly in minority populations, five regional lupus surveillance projects were funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These rigorous studies used several different clinical and laboratory databases for case finding, and employed capture- recapture methodology, which determines the extent of overlap in multiple case- finding sources to adjust for case under- ascertainment. The first registries from Georgia and Michigan were published in 2014, and reported similar overall incidence (5.6 and 5.5 per 100,000 person- years, respectively) and prevalence (73.0 and 72.8 per 100,000 individuals, respectively) rates13,14. These analyses reaffirmed the known disparity between Black and white patients with SLE: the incidence and prevalence of SLE was more than twice as high in Black patients than in white patients and Black patients were diagnosed at an earlier age and experienced renal disease more often (40.5% of Black patients had renal disease versus 18.8% of white patients)13. An additional registry focused on American Indian and Alaska Native populations, finding that the estimated prevalence and incidence equalled or exceeded that of the Black population15.

Subsequently, registries were formed in California and New York, which provided the first accurate portrayal of the burden of SLE in Hispanic and Asian populations. Findings from the California Lupus Surveillance Project were published in 2017, based on data from San Francisco County between 2007 and 2009 (TABLE 1). The overall annual age- standardized incidence was by far the highest in Black women (30.5 per 100,000 person- years) and lowest in white women (5.3)1. Age- standardized prevalence was also higher in the Black female population (458.1 per 100,000 individuals) than in any other ethnicity1. Results from the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Project were published in 2017 and similarly highlighted ethnic disparity inherent to SLE. Incidence rates were highest in non- Hispanic Black women compared with any other group2. The prevalence was also highest in non- Hispanic Black women (221.4 per 100,000 individuals), followed by Hispanic and non- Hispanic Asian women (142.7 and 118.5 per 100,000 individuals, respectively). The prevalence was lowest in non- Hispanic white men (6.3 per 100,000 individuals). Other work has emphasized the increased frequency of SLE in minority populations, with the age- adjusted incidence being twice as high in Arab American and Chaldean American populations than in white populations16.

Emerging data suggest that the prevalence of SLE is rising over time. Analysis of US Medicare data suggest that the age- and sex- adjusted prevalence of SLE was 301.1 per 100,000 individuals in 2009 and rose to 366.6 per 100,000 individuals by 2016 (REF 9). The adjusted incidence rates were similar across this time frame (46.9 and 49.0 per 100,000 in the US Medicare population, respectively). The prevalence of SLE is also increasing over time in Canada, with administrative data from Alberta revealing a stable incidence between 2000 and 2015, but an increase in prevalence from 48 per 100,000 individuals in 2000 to 90 per 100,000 individuals in 2015 (REF 11).

Mortality.

In a comprehensive analysis published in 2017, researchers assessed the trends in mortality of patients with SLE in the USA over almost half a century (1968–2013) using the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System and census data17 ( TABLE 2). SLE was the underlying cause of over 50,000 deaths during this period. The annual age- standardized mortality rate (ASMR) for patients with SLE declined between 1968 and 1975, followed by an increase between 1975 and 1999. Between 1999 and 2013, the mortality again declined. The ASMR was 0.45 per 100,000 individuals in 1968 and 0.34 per 100,000 individuals in 2013, representing a decrease of 24.4%. Over this time, annual ASMRs decreased less for patients with SLE than other patients, who experienced a relative decrease of 43.9%. In a multiple logistic regression analysis, female sex, residence in the South or West, age over 65 and minority ethnic group were individual factors independently associated with a higher risk of death17. Despite the decreases in mortality, SLE was still a leading cause of death in young women in the USA between 2000 and 2015 (REF.6).

Deaths from SLE are unevenly distributed among ethnic groups. In an analysis of data from the Georgia Lupus Registry from 2002 to 2004, in which cases of SLE were matched to data from the National Death Index from 2002 to 2016, the overall SMR for patients with SLE (adjusted for age, sex and race) was three times higher than that of the general population. Black patients with SLE died approximately 13 years younger than white patients with SLE18. The risk of death was also higher in black patients with end- stage renal disease from lupus nephritis than in patients of any other ethnicity with lupus nephritis- related end- stage renal disease (adjusted hazard ratio 1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.7, in patients aged 18–30 years). When adjusted for area-level median household income, insurance status and renal transplantation, this difference was no longer apparent, suggesting that socioeconomic factors drive the disproportionate mortality19. In patients with SLE enrolled in Medicaid, a US government programme that provides health coverage to vulnerable populations, mortality was highest in American Indian patients, followed by Black patients and then white patients. Adjustment for comorbidities and socioeconomic factors attenuated the mortality risk for Black patients, albeit incompletely, but did not affect the mortality risk for American Indian patients. Unusually, the mortality was lower in Hispanic and Asian patients than in white patients, potentially because of the reduced discrepancy in socioeconomic status in the Medicaid population, and lower all- cause mortality in Hispanic patients20.

The largest study to date of mortality in hospitalized patients with SLE in the USA, which analysed data from the National Inpatient Sample, identified almost two million patients who were discharged from hospital between 2006 and 2016 (REF 21). Mortality rates declined from 2006 to 2008 and then remained relatively stable. Black, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander patients had higher in- hospital mortality than white patients21. In a study of almost 175,000 SLE- related hospitalizations in the USA in 2016, the leading cause of in- hospital mortality was infection (38.18%), followed by cardiac disease (12.04%)22. The National Center for Health Statistics multiple cause of death database has also been used to investigate causes of death in patients with SLE23. In this analysis, the most frequently listed conditions among the female patients with SLE who had died were sepsis (4.3%) and hypertension (3.0%), whereas cardiac disease (3.7%) and diabetes mellitus complications (3.6%) were the most frequent conditions among the deceased male patients with SLE. Among the deceased patients, female patients with SLE died on average 22 years younger than female patients without SLE (median age of death for patients with SLE 59 years versus 81 years for those without SLE), whereas this gap was only 12 years for male patients (median age of death for patients with SLE 61 years versus 73 years for those without SLE).

Summary.

Epidemiological studies in North America from the past 5 years have reinforced the concept that SLE disproportionately affects women, and racial and ethnic minorities. CDC- funded registries have provided robust data and generally report slightly higher incidence and prevalence rates than previous studies, probably because of more detailed case findings and adjustments for case under- ascertainment. The effect of increased lifetime expectancy on an apparent rise in prevalence cannot be excluded either. Infection and cardiovascular disease are consistently top causes of death.

Europe

Incidence and prevalence.

Epidemiological studies in Europe are commonly confined to one location. Many European countries have national registries, often linked to a national health insurance system, which cover the entire or major parts of the population. Various studies of European populations have taken advantage of these registries and thus include large numbers of patients and matched controls24–29. However, registry studies rely on case definitions through ICD or similar codes and not on validated clinical cases of SLE. Cohort studies are fewer and smaller than registry studies and describe patients in defined catchment areas and several of these patient populations have been followed over time. In these studies, great effort has been invested in ‘multi- source retrieving’ whereby all prevalent and incident cases are retrieved through multiple sources including chart review, collaboration with other medical specialties, electronic databases, evaluation of antinuclear antibody (ANA)- positive individuals, patient organizations and public campaigns, and in validating that each diagnosis of SLE fulfils classification criteria30–33.

The overall incidence of SLE in Europe varies between 1.5 (REFS 33,34) and 7.4 (REF 30) per 100,000 person- years (TABLE 1). Large registry- based studies in the UK27 and Hungary26 have reported an overall incidence of 4.9 per 100,000 person- years. Other large registry- based studies in Europe have reported lower incidence rates: 3.3 per 100,000 person-years in France28, 2.3 per 100,000 person- years in Denmark25 and between 1.5 and 1.8 per 100,000 person- years in Estonia34. The highest annual incidence, 7.4 per 100,000 person- years, comes from a case retrieval study in Crete, Greece30. The estimated incidence rates reported in other cohort studies have been similar to that reported by the registry studies: 2.8 per 100,000 person- years in southern Sweden31, and 2.0 per 100,000 person- years in a confined region in northern Italy32.

The estimated prevalence of SLE around Europe varies even more than the estimated incidence, ranging between 29 (REF.33) and 210 (REF.35) per 100,000 individuals. In most registry studies, the point prevalence ranges between 30 and 70 per 100,000 individuals24–26,28,29,34, whereas the reported prevalence in the UK is higher, at 97 per 100,000 individuals27. An even higher prevalence, 123 per 100,000 individuals, was reported for Crete, Greece, in the case retrieval study30. In one study in Spain, researchers used an uncommon methodology whereby questionnaires regarding symptoms were sent to a random selection of the Spanish population and positive responses were followed up by telephone interviews; this approach resulted in a final validation of 12 cases of SLE through medical file review or clinical visits. This study yielded the highest observed prevalence of SLE in Europe, at 210 per 100,000 individuals35.

The incidence of SLE in women is approximately 5 times higher than in men and peaks earlier (30–50 years of age versus 50–70 years of age)27,28. Women are consistently disproportionately affected, representing 85–93% of individuals with SLE (TABLE 1). The prevalence of SLE is about nine times higher in women than in men, with a remarkably steep incline in women starting at puberty, whereas the prevalence curve for men has a slower and more even rise throughout life25,27,29.

Most European studies do not stratify for ethnicity. An exception is the registry study conducted in the UK27, which reported a higher incidence and prevalence of SLE in the Black population, especially in individuals of Caribbean descent. Overall, many of the longitudinal studies covering the past few decades describe a declining incidence, but rising prevalence of SLE26,27,30,31.

The substantial variation in incidence and prevalence is probably due to differences in methodologies and case definitions. Several studies demonstrate that through use of more or less strict case definitions, epidemiological figures will vary considerably in registry-based studies27,29,34. The estimates can differ depending on who registered the diagnosis, if the diagnosis is required to be reported only once or several times in the registries, and whether supporting evidence such as medical prescriptions or other data is needed26,28,29.

Mortality.

Studies on SLE- related mortality during the past 5 years have been unevenly distributed across Europe, with five studies from the UK, two from Scandinavia, two from southern Europe and only one from Eastern Europe (TABLE 2). Nevertheless, the SMRs reported in these studies have been fairly consistent, falling between 1.6 and 3.1 (REFS26,36). In two longitudinal studies, the SMRs remained consistent over the past three decades37,38. One study, which also included patients with juvenile- onset SLE (<18 years of age), reported considerably higher SMRs in those with juvenile- onset SLE (SMR 18.3) than in those with adult- onset disease (SMR 3.1)36. Two studies, one from the UK and one from Sweden, reported similar SMRs in men and women37,39, whereas a registry study in the UK reported higher mortality rates in men than in women40 (mortality rate of 13.8 per 1,000 person- years in women and 28.1 per 1,000 person-y ears in men, yielding a female:male ratio of 0.54 (95% CI 0.40–0.73)).

A few studies have looked at risk factors for mortality in European populations, finding that patients with higher damage accrual were at increased risk of mortality in the UK and Italy41,42. A subgroup of patients with juvenile- onset SLE from the UK and a subgroup of patients with lupus nephritis (which is associated with an earlier disease onset) in Norway had considerably higher SMRs than patients with SLE with a later disease onset43,44. In another separate analysis based on data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, comprising 8% of the UK population, higher cumulative glucocorticoid dosage was associated with a higher mortality risk, whereas hydroxychloroquine treatment was associated with a reduced risk of mortality39.

In the majority of studies, cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in patients with SLE, being responsible for 27–52% of fatalities26,37,40,45 (with the exception of one study in Italy that reported a much lower occurrence of only 17%42). Infections are responsible for 15–43% of deaths26,37,41,45, and malignancies account for 13–33% of deaths26,37,40,41,45. Researchers have also investigated the cause-specific mortality for patients with SLE compared with the general population. In one such analysis in Hungary, infections caused a higher percentage of deaths in patients with SLE compared with the general population, whereas malignancy was responsible for a lower percentage of deaths in patients with SLE than in the general population26. In a similar study of a UK population that used fully adjusted models, the researchers noted higher relative risks of cardiovascular disease, infection and respiratory disease in patients with SLE than in the general population, whereas malignancy was a less common cause of mortality in these patients compared with the general UK population39.

Summary.

In conclusion, the epidemiological coverage of SLE in Europe is incomplete, with many studies from the UK, several studies from southern Europe and Scandinavia, but few studies from central Europe and eastern Europe. The incidence and prevalence of SLE varies considerably between different European countries; however, because of the different health- care systems and methodologies used, reliable comparisons are not possible. Mortality rates are more consistent across Europe, commonly being about twice that of the general population. Cardiovascular disease and infection are major causes of mortality, together accounting for the increased mortality rate of patients with SLE compared with the general population, whereas malignancies cause proportionally fewer fatalities than in the general population. Standardized mortality rates are higher for patients with high damage scores and those patients with a younger disease onset, nephritis and/or high cumulative doses of glucocorticoids.

South America

Incidence and prevalence.

With very limited resources to conduct surveillance studies of chronic conditions, the epidemiology of SLE remains unknown in the majority of South American countries. Moreover, although studies from other parts of the world demonstrate disproportionately higher susceptibility to SLE and SLE- related mortality in people of colour, compared with white people, studies in South America that assess population-based statistics by race or ethnicity are lacking.

The most recent estimates of the incidence and prevalence of SLE in South America are from a study conducted in the state of Tucumán, Argentina46 (TABLE 1). The state has a population of nearly one and a half million inhabitants (a predominantly Mestizo population, 60% of whom are under the care of the public health system). In this analysis, individuals aged >16 years with a diagnosis of SLE according to the 1997 ACR revised classification criteria were ascertained across four public hospitals and private rheumatology practices for the period 2005–2012 (n = 353). The annual incidence ranged from 1.4 per 100,000 person- years (95% CI 0.7–2.4) in 2007 to 4.2 per 100,000 person-y ears (95% CI 2.9–5.8) in 2012, with an overall age- adjusted prevalence of 34.9 per 100,000 person- years (95% CI 32.8–41.1) and a female-t o- male ratio of 14.3:1.

In a secondary analysis of a prevalence study of SLE in Colombia that was aimed at indirectly calculating age- specific incidence by sex47 (TABLE 1), researchers found that the incidence for females peaked between the ages of 30 and 39 years, at 20 cases of SLE per 100,000 person- years, and returned to one case of SLE per 100,000 person- years by the age of 45 years47. By contrast, the incidence pattern for men showed a flat curve, with two minor peaks: one peak corresponding to men in their early 20s (2.5 per 100,000 person- years) and the other peak corresponding to men older than 75 years (2.8 per 100,000 person-y ears). In Argentina, researchers have also looked at the incidence of SLE among individuals under the care of a large private health-c are system, which serves 5–7% of the population in the city of Buenos Aires48. The investigators reviewed data from 140,000 individuals being cared for between January 1998 and January 2009 and found 68 new cases of SLE. The overall incidence within this predominantly white population was 6.3 (95% CI 4.9–7.7) per 100,000 person- years, with 8.9 (95% CI 6.6–11.2) per 100,000 person- years for women and 2.6 (95% CI 1.2–3.9) per 100,000 person- years for men. The age- specific incidence for women peaked between the ages of 18 and 29 years, whereas the incidence remained low across all age groups in men. Among the 127,959 active members registered in the system on January 2009, a total of 75 were classified as having SLE48. The overall prevalence was 58.6 (95% CI 46.1–73.5) per 100,000 members (women 83.2 (95% CI 63.9–106.4) and men 23 (95% CI 11.9–40.1)). The age-s pecific prevalence peaked between the ages of 40 and 59 years for women and between the ages of 40 and 49 years for men.

One of the most recent efforts to estimate the prevalence of SLE in South America was conducted in Colombia, using national health data from a centralized system called the Integrated Social Protection Information System, which compiles health data from 95% of the Colombian population49. Cases of SLE were ascertained from 2012 to 2016 using ICD-10 codes. The overall 5- year period crude prevalence was 91.9 per 100,000 individuals, with 126.3 per 100,000 individuals for the population aged over 18 years. After adjustments to the 2014 World Health Organization population, the prevalence rates were 204.3 per 100,000 individuals and 20.2 per 100,000 individuals for females and males, respectively. The crude prevalence in women peaked in the 45–49-year age group (at 391.6 per 100,000 individuals) and in men peaked in the 60–64- year age group (at 46.3 cases per 100,000 individuals).

A population- based study has been conducted to estimate the prevalence of rheumatic diseases in a selected community of Venezuela, using the COPCORD (Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Diseases) methodology50. COPCORD entails three phases: a screening questionnaire provided by trained interviewers to a sample of adult individuals; examination of individuals with musculoskeletal pain by a trained primary care physician; and rheumatic disease confirmation and classification by clinical evaluation (physical examination, labs and radiology) by certified rheumatologists. The study was conducted in a sample of 3,973 individuals from the state of Monagas (population 905,443), and 3 cases of SLE were confirmed. The prevalence of SLE in this sample population was estimated to be 0.07 (95% CI 0.0, 0.2) per 100 individuals50. The COPCORD methodology has also more recently been applied to study the prevalence of SLE in two South American populations: individuals in the city of Cuenca (Southern Ecuador)51 and the indigenous Qom population in Rosario, Argentina52. The estimated prevalence of SLE among a sample of adult individuals from each of those communities was 0.06% (95% CI 0.01–0.1 for the Cuenca sample; 95% CI 0.001–0.3 for the Qom sample).

Mortality.

Population- based studies of mortality in SLE are scarce in South America. However, epidemiological research conducted in Argentina and Brazil in the past 10 years have provided insights into the magnitude of the problem, high- risk groups and leading causes of death in SLE populations.

A study conducted in the state of Tucumán, Argentina, reported 32 deaths among 353 patients with SLE attending various public hospitals and private rheumatology practices between 2005 and 2012, with an overall mortality rate within the SLE cohort of 9.1% (95% CI 6.3, 12.6)46 (TABLE 2). An exploratory ecological study53 that used data from the Mortality Information System of DATASUS, the Department of the Unified Health System (Brazil’s National Health System), examined the mortality and causes of death among patients with SLE in Brazil between 2002 and 2011. This study identified 8,761 deaths among patients with SLE in Brazil, yielding a mortality rate of 4.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. SLE alone was mentioned as a underlying cause of death in 77% of these patients. The national mean age at death was 40.7 (standard deviation (s.d.) 18 years), with death occurring at a significantly (P < 0.0001) younger age in the northern region (34.1, s.d. 13.7 years) than in the southern region (44.7, s.d. 17 years). Other underlying causes of death reported among the patients with SLE included diseases relating to the circulatory system (6.0%), respiratory system (2.2%), digestive system (2.1%) and genitourinary system (1.9%), and infectious and parasitic diseases (2.8%). In another study assessing mortality among patients with SLE in São Paulo state, in Brazil’s Southeast region, during the period 1985–2004, the mean age at death was 35.1 years (s.d. 15.0 years)54. These data together suggest that the survival of patients with SLE might have improved in recent years. However, the data also highlight substantial disparities in age at death, with death from SLE occurring at a lower mean age in the northern and north- eastern regions than that reported for São Paulo state ~10 years prior. As noted by the investigators, the causes of those disparities were multidimensional, including socioeconomic and educational differences, delay in diagnosis, health-c are access barriers and more frequent infections and comorbidities in the northern regions of Brazil than in the southern regions53.

Summary.

Only a handful of studies have been conducted investigating the incidence and prevalence of SLE and the mortality among patients with SLE in South American countries. Because of the scarcity of resources to conduct large- scale population- based surveillance, South American studies rely on administrative data or sampling methodologies to find patients, making it difficult to compare estimates with some studies from other parts of the world. Despite these limitations, epidemiological data from South America highlight that SLE begins at a very young age among women, with the incidence peaking in women in their 20s and 30s. Similarly, although the survival of individuals with SLE in Brazil might have improved in the 2000s, the average age of mortality is still very young. Data from these epidemiological studies are fundamental to advance the understanding of health disparities in the burden of SLE and inform resource allocation in specific regions.

Asia

Incidence and prevalence.

Compared with North America and western Europe, data regarding the incidence and prevalence of SLE in Asian countries are less robust, although Asian patients with SLE have long been recognized to have a more severe disease course than white patients4,55. The largest Asian epidemiological studies have been conducted in Taiwan and South Korea, where large-s cale population-based disease registries have been established and properly maintained56–58. Although most other SLE epidemiological studies have used retrospective cohorts, these studies nevertheless provide an overview of the prevalence and incidence of SLE in Northeast and East Asia. Data from southern and western parts of Asia, including India, the United Arab Emirates, Israel and Turkey, are generally from studies with relatively smaller sample sizes59.

The annual incidence of SLE in Asia varies from 2.8 to 8.6 per 100,000 person- years56–60, and the prevalence ranges from 26.5 to 103 per 100,000 individuals57–61 (TABLE 1). Most of the Asian cohorts were established in the late 1990s and early 2000s and therefore adopted the 1997 ACR classification criteria for SLE. Data generated from these cohorts, which spanned over a decade, demonstrated that both the prevalence and incidence of SLE seem to be increasing in Asia58.

Mortality.

In addition to population-based SLE registries and related studies conducted in Taiwan and South Korea, other SLE centres in Asia have provided invaluable survival and mortality data for patients with SLE across eastern Asia, China (Mainland) and the Middle East region (TABLE 2). The overall 1-y ear, 5- year, 10- year and 15- year survival rates range from 93.7 to 98.4%, 80.4 to 98.6%, 56.5 to 98.2% and 31.7 to 88.8%, respectively56,62–72. The overall SMRs range between 2.1 and 11.1 (REFS 61,62,68,72,73). The most common causes of mortality in patients with SLE include sepsis and cardiov ascular, cerebrovascular and renal disease74. Lupus nephritis is more prevalent and severe in Asia than in Western countries75. Notably, patients with lupus nephritis have a higher SMR than patients with out lupus nephritis in Asia (9.0 versus 4.8)72, and patients with proliferative lupus nephritis have a higher SMR than patients with pure membranous lupus nephritis (9.8 versus 6.1)72. Furthermore, the SMRs of patients with renal damage or end-s tage renal failure are 14.0 and 63.1, respectively72. Prompt recognition and treatment of lupus nephritis are crucial for the management of Asian patients with SLE. Results from a meta- analysis of observational studies published between the 1970s and 2010s76 suggest that renal damage has impeded further improvement of short- term and long- term survival in patients with SLE over the past five decades.

Summary.

Serious organ manifestations of SLE, renal disease in particular, remain prevalent in the Asia Pacific region. More work is needed to elucidate the pathophysiology of renal disease in SLE before more effective and targeted disease monitoring and therapy can be implemented. The aggressive nature and poor outcome of renal disease in Asian patients with SLE underscores the urgent need for more efficacious and less toxic regimens.

Australasia

Incidence and prevalence.

The incidence and prevalence of SLE in Australia and New Zealand have been difficult to ascertain owing to a lack of large- scale population- based disease registries. All studies have been retrospective in nature, and catchment areas were dependent on participating physicians recording clinical features, diagnosis and other epidemiological data. TABLE 1 presents summarized data from these studies. Limited data have been published on the incidence of SLE, with only one study available that examined new cases of SLE between 1986 and 1990 in the Aboriginal Australian population of the Northern Territory, reporting an annualized incidence of at least 11 per 100,000 person- years77. The overall prevalence of SLE has ranged from 13 to 89 per 100,000 individuals on the basis of studies from Australia and New Zealand77–81. Two of these studies have also examined ethnic differences in the prevalence of SLE in Australia and New Zealand, finding an increased prevalence in the indigenous (Aboriginal Australian and New Zealand Polynesian) populations (age- adjusted prevalence rates of 51–73 per 100,000, compared with 15–19 per 100,000 white individuals)78,81.

Most SLE epidemiology studies in Australasia were performed in the 1980s to 1990s, and hence it is difficult to comment on temporal trends, given the lack of more recent data. A single study used the 1997 ACR classification criteria82 to define cases of SLE, but no study has used the newer Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC)83 or EULAR–ACR classification criteria84.

Mortality.

SLE- related mortality data in Australasia are limited and mostly presented in studies comparing indigenous (Aboriginal Australian or Torres Strait Islander) populations with white populations77,78,80 (TABLE 2). Survival rates are lower in indigenous groups than in white populations, with a 5-y ear survival of 60% in one study77. Of the three studies that reported mortality data, the consistent causes of death were active disease associated with intercurrent sepsis or acute thromboembolic events. Poor adherence to medication was also highlighted as a potential factor in one study78. The mean disease duration by the time of death was usually short, ranging from 4 months to 8 years77,78,80. Deaths during periods of quiescent disease were usually due to cardiovascular disease77,80.

Ethnicity, as a single demographic variable, has been the most widely reported determinant of unfavourable outcomes in SLE, reported in the literature on Australian and New Zealand populations. Unfortunately, details of the disease course and treatment trajectories were not available from these mortality studies. Ethnicity can certainly have an effect on disease severity, but other socioeconomic factors might also affect certain ethnicity groups, such as access to medical care and adherence to treatment, which might notably influence disease outcomes.

Summary.

There have not been many studies exploring the epidemiology of SLE in Australasia. Most studies explored the ethnic difference between the indigenous and white populations, demonstrating an increased prevalence of disease in the indigenous groups. With the changing landscape of demographics in the region, updated studies inclusive of other ethnicities will help to fill the knowledge gap. Furthermore, there has only been one study examining the incidence of SLE in Australia, taking observation from populations living in the Top End of the Northern Territory. The lack of large- scale population- based longitudinal studies has meant that the prevalence and incidence rates may not be reflective of the broader Australasian cities. Most existing studies also relied on relatively dated classification criteria. With the availability of revised classification criteria that have better sensitivity and specificity, future studies to explore longitudinal outcomes such as incidence rates and mortality may find a change in the epidemiology of the disease in the region.

Africa

Incidence and prevalence.

In high- income countries, individuals of African ancestry are disproportionately affected by SLE compared with individuals of other ancestries. The burden and natural history of the disease in Black Africans remains a subject of controversy. Two decades ago, epidemiological studies of SLE in Africa were few, limiting the understanding of the disease in the sub- continent. This lack of evidence was often cited as the basis for the assumption that SLE is rarer in Black Africans than in people of African descent in the Americas and Europe, otherwise known as the ‘lupus prevalence gradient’85. In the past 5–10 years, newer evidence has emerged suggesting that the prevalence gradient hypothesis is an artefact of the limited resources in Africa, including the presence of few specialists and the possibility of missed and misdiagnosis of SLE in these populations86–88.

An abundance of case series, and more crucially, cross- sectional and cohort studies (albeit hospital- based)87,89, are now available, enabling an estimation of the burden of disease and phenotype of SLE in Africa. For example, one survey of members of the African League Against Rheumatism in 2013 revealed that 20% of these clinicians (spanning rheumatology, general practice, nephrology and dermatology) had seen more than 50 new patients with SLE in the previous 12 months, indicating that the incidence of this condition is not negligible87. However, accurate estimates of the incidence of SLE and longitudinal studies of this disease are unavailable. We identified seven studies from six African countries based on rheumatology clinics and hospitalized patients90–96 ( TABLE 1). There was considerable heterogeneity in prevalence by location among these studies: 601 and 7,713 per 100,000 individuals in Cameroon91 and Senegal96, respectively. However, these estimates do not reflect the true population prevalence of SLE in Africa. Although these estimates seem much higher than prevalence estimates from other regions, they are not comparable with population- based (and registry- based) estimates from other settings and might be subject to surveillance bias; for example, hospital- based surveillance systems often comprise individuals with more severe sequelae than in other settings. Similar to the age distribution among Black individuals with SLE in other settings, SLE seems to disproportionately affect young women in Africa. The median age at presentation ranged from 29 to 39 years, and women comprised between 91% and 100% of the patient population in Africa90,92–96.

Mortality.

Assessment of outcomes and comorbidities regarding SLE in Africa confers unique challenges. Serological tests and biopsies are mainstays of the management of SLE; however, the limited availability of these diagnostic and prognostic tools in low- income settings in Africa hinders clinical management87. For example, many hospitals in these regions are unable to perform renal biopsies because of the prohibitive costs and the lack of nephrologists and histopathologists87. Because of valuable investments in the advancement of nephrology in Africa by the International Society of Nephrology, the increasing prevalence of lupus nephritis in renal registries provides further evidence of the disproportionately high morbidity due to SLE87. Synthesis of the evidence from renal registries suggests that lupus nephritis might comprise up to 29% of renal biopsies performed in Africa87. Between around 5% and 51% of patients with SLE have renal manifestations97–99. The other most common SLE manifestations were cutaneous involvement (up to 96% of patients) and arthralgia (up to 53% of patients)90–96. In one study, Jaccoud arthropathy was found in 5% of patients94. Reported in- hospital mortality in patients with SLE ranges between 0% and 44% in studies, with follow- up times ranging from 3 days to 10 years91,93,97–100 (summarized in TABLE 2). Frequently listed causes of death in these studies were infections, end- stage renal disease and neuropsychiatric manifestations91,93,97–100. The most common treatment regimens for SLE are anti- malarial drugs, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, azathioprine and NSAIDs90–96. However, the routine use of first- line and second- line drugs might be prohibitive owing to limited affordability and the challenges of counterfeit drugs in some regions89,101,102.

Summary.

Emerging evidence suggests that the burden of disease and natural history of SLE in Africa might be similar to trends identified in patients of African ancestry in other settings. A few considerations unique to this region have also emerged. A sustained investment in SLE research in Africa is needed, as well as capacity building by international rheumatology organizations, including collaborations with programmes such as the Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) consortium, funded by the NIH and Wellcome Trust103. H3Africa seeks to apply genomic science to understand genetic and environmental contributions to the risk of chronic disease in Africa. Leveraging H3Africa for SLE research would propel the understanding of SLE risk and its clinical course. Another consideration is that the burden of infections in the general population of Africa is high104. Co- infection with bacteria (such as those linked with tuberculosis) and/or viruses (such as the human immunodeficiency virus and those linked with hepatitis) can complicate the management of SLE, particularly in the choice of treatment regimens that could potentially reactivate dormant infections87,89. Although these conditions are of relatively low prevalence in developed countries, longitudinal studies on the course of these infections in patients with SLE in Africa are warranted.

Global trends

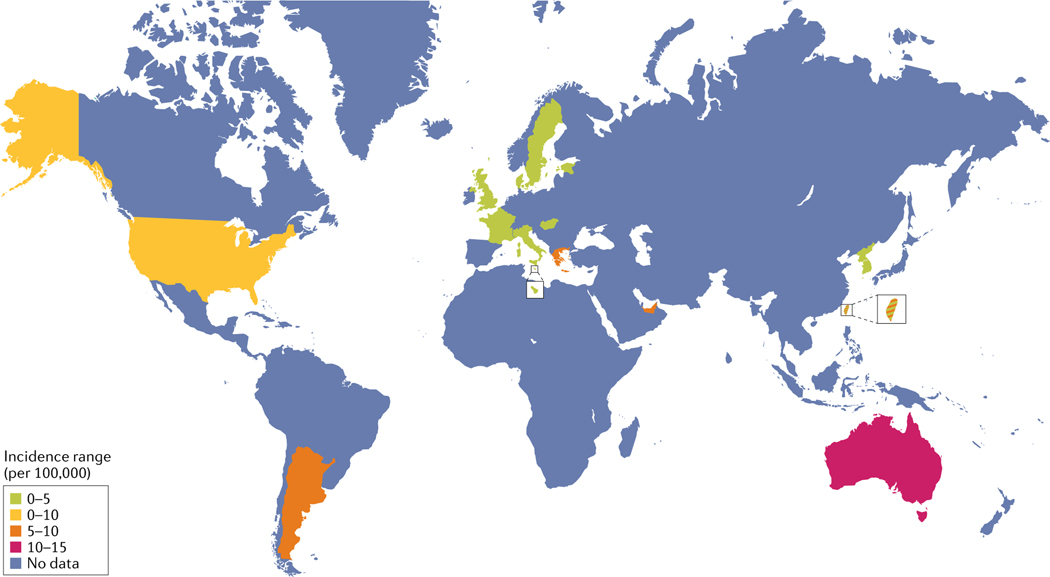

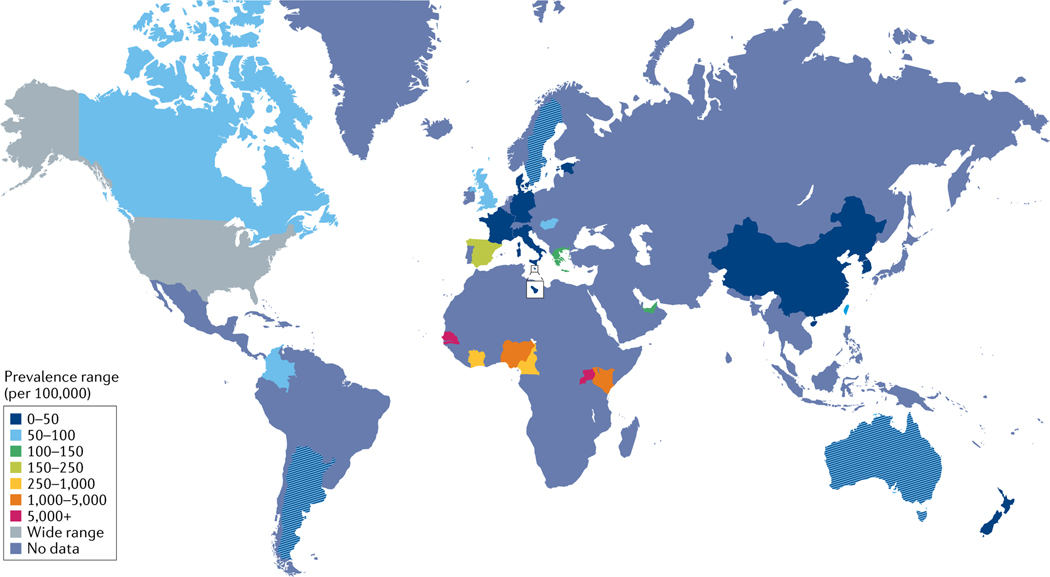

Recent overall SLE incidence rates vary between 3.7 per 100,000 person- years10 and 49.0 per 100,000 in the US Medicare population9 in North America, 1.5 and 7.4 per 100,000 person- years in Europe30,33, 1.4 and 6.3 per 100,000 person-y ears in South America46,48 and 2.5 and 8.6 per 100,000 person- years in Asia58,59. Estimates of the current incidence of SLE in Australasia or Africa are unavailable. The prevalence of SLE varies between 48 and 366.6 per 100,000 in North America9,11, 29.3 and 210 in Europe33,35, 24.3 and 126.3 in South America46,49, 20.6 and 103 in Asia58,59, 13 and 52 in Australasia77,79 and 601.3 and 7,713.5 in Africa91,96. These ranges are summarized in FIG. 1 and FIG. 2. Values have not necessarily been adjusted using the same methods, and prevalence estimates seem much higher in Africa than in the rest of the world but are unlikely to reflect true population prevalence, as they are based on hospital and clinic samples.

Fig. 1 |. Global incidence estimates for SLE.

The figure shows the reported incidence ranges for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) per location (per 100,000 of the population), as denoted by the key. Not all data have been collected and reported uniformly across global regions. Precise overall prevalence ranges per region are outlined in TABLE 1, in which data for China mainland and Taiwan are listed independently. Nature Reviews Rheumatology remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps.

Fig. 2 |. Global prevalence estimates for SLE.

The figure shows the reported prevalence ranges for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) per location (per 100,000 of the population), as denoted by the key. Not all data have been collected and reported uniformly across global regions. Prevalence estimates seem much higher in Africa than in the rest of the world but are unlikely to reflect the true population prevalence, as these data are based on hospital and clinic samples. Precise overall prevalence ranges per region are outlined in TABLE 1, in which data for China mainland and Taiwan are listed independently. Nature Reviews Rheumatology remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps.

Although comparing regional studies that use distinct methodology is difficult, international studies have offered insight into global trends. Data from the World Health Organization mortality database have been used to calculate an international ASMR for SLE105. In 2014, the ASMR was 2.7 deaths per million inhabitants: 4.5 deaths per million inhabitants for women and 0.8 deaths per million inhabitants for men. The ASMR decreased between 2001 and 2003 (−6.4%, P < 0.05) followed by a minor increase between 2004 and 2014 (0.6%, P < 0.01). Mortality rates were strikingly heterogeneous between countries, with a several hundred-f old variation between countries, from 0.1 deaths per million inhabitants in Morocco to 27.1 deaths per million inhabitants in Saint Lucia. In 2014, the highest overall ASMR was in Latin America and the lowest was in Europe. The researchers suggest that this variation might be because of differences in disease severity, socioeconomic factors, reporting biases and treatment capacity105. Mortality rates were higher for SLE than for five other systemic autoimmune diseases, including systemic sclerosis, idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, Sjögren syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease and anti- neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis.

Frequent causes of mortality include infection, cardiovascular disease, malignancy, as well as sequelae from active disease such as renal failure. A comprehensive international meta- analysis of all- cause and cause- specific SLE mortality was published in 2016 (REF.7). In this study, the researchers analysed data from 15 studies, including data from >26,000 patients and >4,640 deaths, and representing data from Asia, Europe and North America from 1999 to 2010. The overall all-cause SMR for patients with SLE was 2.6. The highest cause- specific SMRs were infection (5.0), renal disease (4.7) and cardiovascular disease (2.3).

A systematic review and meta- analysis of survival studies between 1950 and 2016 showed increasing survival in both high- income countries and low- or middle- income countries until the mid1990s, followed by a persistent plateau. In adults, the 10- year pooled probability of survival estimates were 0.89 in high- income countries and 0.85 in low- or middle- income countries106. Infections were the main cause of death in both high- income countries (15.1%) and low- or middle-income countries (37.5%), whereas cardiovascular disease was responsible for 11.3% and 10.6% of deaths, respectively. This knowledge is crucial, because infection might be a modifiable cause of death in patients with SLE.

Although only one new therapy for SLE, belimumab, has been approved in more than half a century, improvements in existing care can likely improve outcomes. In a Delphi consensus study, a multidisciplinary panel of experts on SLE convened to create a list of 25 SLE-s pecific adverse outcomes thought to be modifiable8. Many of these adverse outcomes relate to frequent causes of mortality such as infections, cardiovascular disease and renal disease. Modifiable infectious outcomes include vaccine-p reventable infections including cervical dysplasia from human papillomavirus, herpes zoster, hepatitis B, influenza, meningococcal disease and pneumococcal disease. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving moderate to high doses of steroids might also be preventable with prophylaxis8. Possibly remediable cardiovascular conditions include recurrent myocardial infarction, and embolic stroke and thrombosis in patients with SLE and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. The development of end- stage renal disease in patients with lupus nephritis was also thought to be potentially preventable. The consensus study included a list of recommendations to circumvent these poor outcomes8. Incorporation of these recommendations into guidelines and clinic quality metrics might improve cause- specific mortality. Future epidemiological studies should determine the incidence and prevalence of potentially remediable SLE- specific adverse conditions and deaths, to help to prioritize resource allocation and improve the quality of care of patients to reduce potentially avoidable deaths. Similar studies should be performed internationally to create regional recommendations for preventable conditions, such as endemic infections.

Methodological issues

Although some variation in the international incidence and prevalence of SLE is accounted for by intrinsic population factors such as ethnicity, environmental exposures and socioeconomic factors, inconsistencies in study design limit the ability to make regional comparisons.

Cohort studies are unable to capture changes in incidence over time, and are typically conducted in tertiary centres, which might attract patients with more complex disease. Studies that use death records might be inaccurate owing to reliance on diagnostic codes, as opposed to physician-confirmed cases. Rigorous registries such as those funded by the CDC in the USA have notable advantages, as these registries interrogate several different databases and utilize capture- recapture methodology, which enables the assessment of whether any cases have been missed. Consequently, these studies are more likely to portray the true burden of SLE. Large registries have also been established in Europe24–29, South Korea and Taiwan56–58. The establishment of further registries that use common methodology across international locations would enable a more accurate comparison between regions.

The definition of SLE also affects epidemiological analyses. The Rochester Epidemiology project identified incident cases of SLE in Olmsted County, Minnesota, that fulfilled either the ACR 1997 or the SLICC 2012 SLE classification criteria. Use of the SLICC 2012 criteria resulted in a higher estimation of the incidence rate than use of the ACR 1997 criteria (4.9 versus 3.7 per 100,000 person-y ears), due primarily to the identification of cases of renal-limited disease and serological abnormalities10. Similarly, in the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program, use of the SLICC definition resulted in a higher estimation of the prevalence and incidence rates than the ACR criteria, with 20.2% of patients meeting only the SLICC definition and 4.3% meeting only the ACR criteria2. In September 2019, EULAR and the ACR published new criteria for the classification of SLE, which require a patient to have a positive ANA test result at a titre of at least 1:80 to be classified as having SLE84. Most epidemiology studies of SLE have used the ACR 1982, ACR 1997 or SLICC 2012 criteria, none of which requires a positive ANA test result. In the SLICC inception cohort, 6.2% of patients with SLE were ANA- negative107 at cohort enrolment, although a systemic review and meta- regression have shown that only ~2% of patients with SLE remain ANA-negative throughout their disease course108. Future epidemiological efforts that use these new EULAR–ACR classification criteria will exclude this subpopulation of ANA- negative patients. Furthermore, the ANA entry criterion might hinder the diagnosis of SLE in regions such as Africa, where serological testing is often sent abroad and is expensive87. More research is warranted to understand the unintended consequences of this requirement in resource-l imited settings. Disease activity indices that use clinical measures instead of laboratory measures, such as the Lupus Foundation of America Rapid Evaluation of Activity in Lupus Index, might benefit disease management in Africa because these tools reduce the need for cost-p rohibitive tests109.

Conclusion

The overall global incidence of SLE ranges between 1.5 (REF.33) and 11 (REF.77) per 100,000 person- years, and the global prevalence ranges from 13 to 7,713.5 per 100,000 individuals79,96. This striking variation in the reported burden of SLE is in part due to inherent differences in population structure such as sex distribution, ethnicity and environmental exposures. However, reporting bias, study design, case definition and SLE classification criteria also affect estimates of the incidence and prevalence, and variability can be high even within the same region. Women are consistently more affected by SLE than men across international regions. Black, Hispanic and Asian populations are disproportionately affected by SLE, with higher incidence and prevalence rates in these populations than in white populations1,2. Several studies from North America, Europe and Asia show a gradual increase in SLE prevalence over time9,30,31,57, perhaps owing to increased recognition of the disease. Mortality among patients with SLE is still unacceptably high, being two to three times higher than that of the general population. The most consistent causes of death internationally include infection and cardiovascular disease, which can probably be mitigated through improved quality of care. Population-based studies in the developing world are urgently needed to understand the global burden of disease, potentially preventable outcomes and to what the extent lack of specialized health-care providers, diagnostic tests and therapeutics affect SLE diagnosis and care.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

The estimated incidence, prevalence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) vary considerably between geographic regions.

Factors that contribute to the variation across different regions include differences in ethnicity, environmental exposures and socioeconomic status but non- uniform SLE definitions and study design also contribute.

Population- based studies in the developing world are urgently needed to understand the global burden of disease.

Mortality in patients with SLE is still unacceptably high, being two to three times higher than that of the general population.

Infectious diseases and cardiovascular disease are consistently top causes of death in patients with SLE.

Even without the development of new therapies, SLE outcomes may be improved by focusing on remediable SLE- specific adverse conditions.

Footnotes

Competing interests

A.E.C. has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Exagen Diagnostics and GlaxoSmithKline. A.M. has received consulting fees from Janssen and research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen. C.D. is supported by a GlaxoSmithKline award (ID 0000048412). E.S. has received honoraria from Janssen and Lilly. R.R.-G. has received research grants from Exagen Diagnostics and consulting fees from Thermo Fisher Scientific and Aurinia Pharmaceuticals. A.H. has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Janssen and AbbVie, and research grant from Merck Serono. M.R.W.B has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Genzyme. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Rheumatology thanks G. Pons-Estel, who co-reviewed with R. Quintana; and G. Bertsias for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Review criteria

A comprehensive search was developed by J.P. in conjunction with the other authors. The search terms used for this project were “systemic lupus erythematosus”, “mortality”, “incidence”, “prevalence” and “socioeconomic factors”. Terms were also compiled for the geographic regions of interest (by continent): North America, South America, Asia, Australia, Africa and Europe. The searches were performed in MEDLINE via PubMed (1966-present). Search results were limited to those items published in the English language and using the MEDLINE human filter. The initial strategy was to include data from the past 5 years, but to represent areas where resources might be limited older studies were included when they were informative. The authors also used additional references of particular interest that were not included in the formal search.

Prevalence The total number of cases of disease in a given timeframe.

Incidence The number of new cases of disease during a specified timeframe.

Capture-recapture Methodology A method that determines the extent of overlap across multiple case- finding sources to adjust for case under- ascertainment.

Point prevalence The prevalence of a disease at a specified point in time.

Jaccoud arthropathy A form of chronic, non- erosive, reducible arthropathy that can affect patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-021-00668-1.

References

- 1.Dall’Era M. et al. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in San Francisco County, California: the California Lupus Surveillance Project. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69, 1996–2005 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Izmirly PM et al. The Incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in New York County (Manhattan), New York: the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69, 2017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pons-Estel GJ, Ugarte-Gil MF & Alarcon GS Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol 13, 799–814 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]