Abstract

With wearable, relatively unobtrusive health monitors and smartphone sensors, it is increasingly easy to collect continuously streaming physiological data in a passive mode without placing much burden on participants. At the same time, smartphones provide the ability to survey participants to provide “ground-truth” reporting on psychological states, although this comes at an increased cost in participant burden. In this paper, we examined how analytical approaches from the field of machine learning could allow us to distill the collected physiological data into actionable decision rules about each individual’s psychological state, with the eventual goal of identifying important psychological states (e.g., risk moments) without the need for ongoing burdensome active assessment (e.g., self-report). As a first step towards this goal, we compared two methods: (1) a k-nearest neighbor classifier that uses dynamic time warping distance, and (2) a random forests classifier to predict low and high states of affective arousal states based on features extracted using the tsfresh python package. Then, we compared random-forest-based predictive models tailored for the individual with individual-general models. Results showed that the individual-specific model outperformed the general one. Our results support the feasibility of using passively collected wearable data to predict psychological states, suggesting that by relying on both types of data, the active collection can be reduced or eliminated.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s41666-019-00064-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Machine learning, Wearable health monitors, Individual-specific modeling, Ambulatory assessment

Introduction

Social and behavioral sciences have seen a surge in studies that strive for ecological validity. Ecological momentary assessment studies (EMA, [44])—in which self-reports and (sometimes) physiological measurements are collected intensively over time from many participants in their natural environments—have grown desirable for their ability to capture moment-to-moment dynamics between variables, while offering ecological validity and the potential to reduce recall bias [42]. The recent advances in miniaturizing computers have the potential to expedite advances in personalized health care. For example, wearable monitors (e.g., Empatica E4, sociometric badges, EEG bands) provide high-quality, real-time, ecologically valid physiological and social data streams in real-life contexts, often with minimal burden to participants. Data from wearables have shown promise to help identify psychological states such as stress [17, 19], or emotional arousal [34]. These are relatively unobtrusive means to monitor individual’s health indicators over time and provide data that may eventually serve as a solid basis for efficient interventions (e.g., by identifying moments of risk). For example, being able to predict psychological states from wearable device data would allow for contributing to the design of cost-effective prevention and intervention programs; for example, helping prevent costly negative health outcomes and support the adoption or maintenance of positive health behaviors. Before wearable data can be used to inform intervention, however, well-designed analytical approaches are needed to distill it into actionable decision rules. The current study provides new insights into optimally selecting such approaches.

Recently, frameworks such as ecological momentary intervention (EMI [18]) and just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAI [32]) have emerged as ways to implement practices that take the individual’s needs and context into account in attempts to deliver interventions to promote positive health and psychological outcomes, or to change behavior in sustainable ways. These frameworks frequently leverage technology to deliver interventions that come at the right time and that are targeted to an individual’s physical and psychological state, and their surrounding context. For many existing EMIs or JITAIs, the deployment of an intervention prompt is based on simple and static decision rules, such as one standard deviation change in self-reported negative affect [41] or after 30/60/120 min of being physically inactivity during awake time (based on accelerometer data; [4]). Although some of these rules have shown promising results, comprehensive reviews [15, 30] on mHealth approaches have provided mixed results regarding their effectiveness. One difficulty faced by these simple rules is that the psychological states (e.g., stress, craving), which are a target of many interventions, are assessed via self-report, requiring participant input and limiting collection density (due to participant burden). In contrast, ongoing assessment of physiological states does not result in high participant burden; however, such data do not provide simple indications of these target states. Moreover, participants might show a level of heterogeneity that renders simple, one-fits-all decision rules inefficient. We need to look for more intricate and precisely tailored data analytic approaches for solutions to these problems.

The combination of intensive real-life data together with person-tailored data-analytical approaches offers the potential to both maximize impact and minimize user burden in participant assessment and intervention. The use of machine learning tools to analyze passively collected data, such as physiological parameters, has demonstrated promise to predict psychological states of interest (e.g., emotional arousal, stress, happiness; see [20, 23, 28, 31, 47, 47]). Ideally such prediction should consider multiple individual-specific variables, collected passively (e.g., GPS location, noise level, electrodermal activity) and/or actively (e.g., self-reported stress, cravings) and their dynamical interplay. To date, however, many studies in this area focus exclusively on population-level inferences, looking at differences between or relationships among group-level means. Although such approaches can be informative for other research questions, they do not address intra-individual dynamics, heterogeneity across individuals, or allow for ideographic information necessary for a range of clinical applications (e.g., just-in-time intervention). The richness of data from intensive micro-longitudinal studies (such as EMA) and passive sensors provides a new avenue of building models for each individual, allowing scientists to capture characteristics specific to an individual, and avoiding the biases associated with group-level inference [29].

Time-series analysis techniques are frequently used to analyze physiological data for prediction of psychological states. Typically, non-linear features of the physiological data time-series are used as predictors of a pre-identified outcome state, although those specific features might differ across contexts and signals.

For example, in time-domain analysis, electrodermal activity data (recorded e.g., before, during and after a stress task) is separated into tonic and phasic parts with the phasic signal further separated into non-specific and event-related skin conductance responses (see, e.g., [5]), with the latter representing fast changes in EDA levels and typically having the most predictive power for stress. When analyzing in the frequency domain, spectral power levels in frequency bands can be tested for their predictive power and have been shown to be reliable predictors of for example cognitive stress under water [35]. It is also possible that the most powerful set of predictors vary from participant to participant—the current work addresses this question.

In the study described below, we tested two machine learning approaches on using passively collected physiological data to predict psychological state; one is a distance-based classification while the other one uses time-series features extracted from the physio data for classification. Our goal was to infer a person’s responses to psychological survey questions based on the physiological indicators, without the burden of asking. If shown to be feasible and accurate, this opens up a number of important research and clinical opportunities. First, we can simply infer (at least some) psychological states from passively assessed physiology, thus tracking psychological states over time without the ongoing burden of repeated self-report assessments, enabling long-term tracking and/or screening of potential psychological risk factors (e.g., stress, depression). Second, this approach could be used to efficiently identify critical psychological states; that is to use passive collected physiological information to infer psychological states of need and use this information to dynamically trigger some response (e.g., clinical support, a just-in-time intervention). As noted, this has the potential for ongoing monitoring over lengthier periods of time without placing undue reporting burden on a person but still providing sufficient information for individual-specific intervention approaches. Finally, even if precise estimation of a (perhaps complex) psychological state is not fully possible, the ongoing physiological indicators could be used to trigger self-report assessments at critical moments, allowing for thorough self-report assessments only when needed.

In what follows, we describe an EMA study in which data was collected from individuals while they were living their everyday life, using a combination of wearable physiological monitors and smartphone-based psychological surveys. Then, we build two machine learning classifiers, k-nearest neighbors and random forests, to predict the psychological state of high or low arousal for individuals based on time series of physiological data collected with wearable health monitors. Having described how we processed the time-series data, we first examine the prediction performance of the two classifiers in terms of how well we can predict self-reported arousal from the two classifiers, using passively collected physiological data. Second, we examine the differences among models created specifically for each individual versus an individual-general model. We conclude that analyzing physiological data with machine learning tools is a promising direction, but that individual-specific solutions are necessary for an efficient prediction framework.

An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study on Daily Experiences

Study Setting

The data in our study (conducted at Pennsylvania State University, USA, under IRB #00001017) was collected from 25 participants who enrolled to a 4 week-long EMA study on well-being in everyday life. Participants from the local community self-selected for the study by replying to an advertisement. To be eligible, participants needed to be at least 18 years old; in the final sample, the the age ranged from 19 to 65, with a mean age of 30 and a standard deviation of 10 in the final sample. The ethnic breakdown was 81% White, Caucasian; 6% Hispanic, Latino; 4% Black, African-American; and 10% Asian or Pacific Islander, with 67% female. Participants were informed that the study protocol consisted of (1) filling out short web-based Qualtrics surveys via their own smartphones six times a day for four weeks; (2) wearing the Empatica’s E4 [33] wristband during that same time; and otherwise going on with their everyday life. Participants were paid in proportion to their response rate to self-report surveys, with maximum payment of $200. After consent, the participants provided their phone number and were registered with a text messaging service. Participants received the survey prompts via text message that had a link directing them to the Qualtrics survey. The surveys were brief and they consisted of questions related to daily experiences, including evaluations of “core affect” (valence/pleasantness and arousal/activation; [39]) and other questions related to their overall well-being (e.g., feelings of love, sense of accomplishment). Over the course of the 28 days, participants could respond to up to 168 text-message prompted surveys. The Qualtrics links expired 30 min after they were sent to ensure timeliness of the response. Compliance was high, with participants completing on average 160 surveys (SD = 9.15).

During the introductory session, participants were also instructed about how to wear and charge the E4 wristband and how to upload their data. Because of the limited battery and storage capacity of the device, participants were instructed to wear the device continuously for two days and during the night between, removing the device to recharge and upload data every other night during their sleep time. This results in continuous data recording for a sequence of Day-Night-Day followed by a night without data collection. On average, 478 h of wearable data was recorded (SD = 62.83).

Actively Collected Self-Reports on Psychological States

In this paper, we focus only on self-reported arousal levels of the person’s core affect, measured by the question “How awake/active do you feel right now.” Participants rated their experiences on a visual analog sliding scale, which appeared as a continuous slider with labels “Not at all” and “Extremely” marking the two endpoints.

Passively Collected Physiological Data

Empatica’s E4 contains four primary sensors. A photoplethysmographic (PPG) sensor measures blood volume pulse (BVP) at a rate of 64 Hz (measurements per second), from which cardiovascular information such as heart rate and heart rate variability may be derived. Tonic electrodermal activity (EDA) also called Skin Conductance Response (SCR) is recorded at 4 Hz using a pair of stainless-steel electrodes mounted on the underside of the band, which reports electrical properties of the skin that have been linked to a variety of measures related to arousal and stress (e.g., [46]). A 3-axis accelerometer captures motion of the wrist at a sampling rate of 32 Hz as a proxy for overall body movement. We derive one “data stream” (time series sequence from one sensor), labeled ACC, consisting of the root mean square acceleration over the x, y and z coordinates in the accelerometer data stream. Finally, the E4 is also equipped with infrared thermopile reading peripheral skin temperature at 4 Hz. The unique combination of available information from these sensors allows researchers to leverage the information potentially gleaned from multiple data streams; that is, to study the predictive power of changes in skin conductance with cardiovascular features estimated from blood pulse volume, such as heart rate and heart rate variability, while also correcting for physical activity.

Data Preprocessing

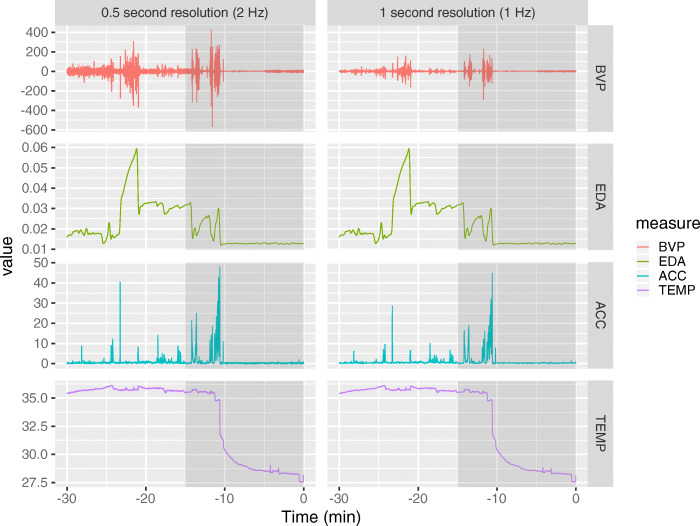

As mentioned earlier, the sensors report measurements at different speeds. The PPG sensor reports BVP at 64 Hz, the accelerometer reports at 32 Hz, while EDA and Temperature are measured at 4 Hz. We downsampled the raw data streams to 1 Hz (one measurement every second), and computed the mean of the raw data in that interval, as we aim at developing models that can do timely computations for near real-time inference. Although there is no clear theoretical reasoning for the specific choice of 1 s windows, we found that sampling at less than 1 s per measurement greatly increases memory requirements and computational time without much corresponding increase in accuracy. Limited pilot testing showed minimal impact on the accuracy of prediction of reported arousal. As seen in Fig. 1 below comparing 1 Hz and 2 Hz resolution, some information is indeed lost in downsampling, especially in terms of acceleration and BVP, which vary more rapidly than other indicators. However, we show in the later analysis that sufficient information is kept for reasonable prediction of high and low reported arousal states.

Fig. 1.

Plot of 4 data streams (BVP, EDA, Temperature, and Acceleration) for one individual within 1 h of a survey (at T = 0). In gray, we show the measurements in a 15 min window prior to the survey for predicting the survey itself. Here we compare the same time series at 0.5 s and 1 s resolution

Machine Learning Approaches to Classifying States

Machine learning (ML) techniques are rising in importance in the social and behavioral sciences. For example, feature selection methods using random forests have been applied to the analysis of well-being across age (e.g., [10]), computer vision methods have been used to analyze conversation (e.g., [3, 8, 38]), convolutional neural networks, support vector machines, and other ML classifiers have been applied to neuroimaging (e.g., [14, 22]) and emotion data [2, 9, 21, 45]), k-means and related clustering methods have been applied to distributions of emotion (e.g., [37, 45]), and process models such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) have been applied to child behavior (e.g., [40, 43]).

Our goal was to detect meaningful states of reported emotional arousal. We focused on distinguishing the low and high arousal states from short (15 min) time-series sequences of physiological data from the wearable device. The selected physiological predictors were based on the available information from the E4, namely electrodermal activity, blood volume pulse, acceleration and temperature data streams seen in Fig. 1. For each individual, we created a dataset using the 20 highest reported arousal values and the 20 lowest reported values. The predictor data for each response is the 15 min of physiological data streams (at 1 s resolution) prior to the self-report.

We then ran a simple binary classification: given a time series X = [x1⋯xk] of physiology during the 15 min leading up to each self-report, we output a label of “High” or “Low” according to the model’s prediction of where the corresponding self-report will fall. This approach of picking out extremes for binary classification was chosen to reduce ambiguities in training by using high confidence states. In practice, we found that the cutoff of 20 upper versus 20 lower captured extreme values, yet it gave us enough samples to train the classifiers and provided a proof-of-concept for future work. In future applications, we expect that this number of self-reports would not constitute an undue burden on participants but could be used to train the models.

k-nearest Neighbors Classification Algorithm with Dynamic Time Warping Distance

We predicted the binary classification using two classifiers. The first was the k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) classification algorithm using a distance based on dynamic time warping (DTW) of the signal stream. The k-NN classification algorithm using DTW distance is a long-standing classifier known to be very efficient for time-series data, and is treated as a “gold standard” for time-series classification across the last decade [13]. This approach works directly on the time series and can be thought of as a computational implementation of a very simplistic model of classification. Specifically, given a novel time series, the k-nearest neighbors approach calculates distances between the new time series and all time series of the training set according to a similarity metric. The k most similar time series in the training set are identified, and the new series is then classified using the labels of those k time series (majority vote). Class probabilities, necessary for calculating area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC; definition in Section 3.3), are found by calculating the proportion of votes for each class within the set of k neighbors.

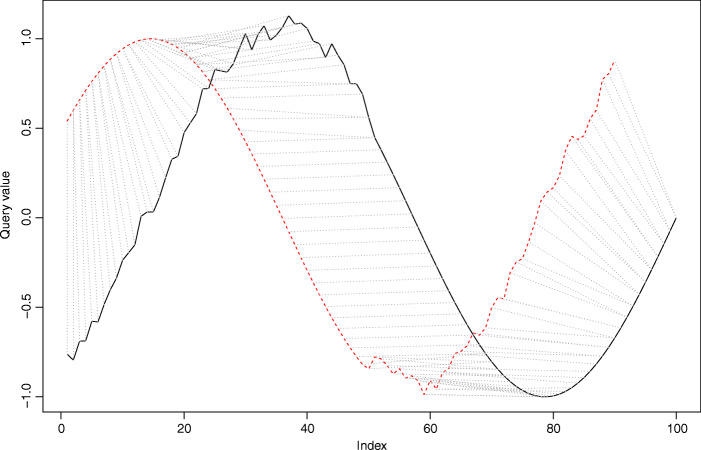

The k-NN algorithm requires a “distance” metric, which determines similarity between two time-series sequences. Dynamic time warping (DTW; [1]) distance is especially suitable here, because it provides a measure of similarity that is invariant across changes in the scale and shift of the series [24]. DTW first computes the optimal alignment between two time series, by allowing one series to “stretch” or “contract” in the time domain, and then reports the (final minimized) distance between aligned elements. Figure 2 below shows an example alignment between two sequences of data. These two sequences show very similar patterns, but shifted somewhat in time, and with slightly different scales; DTW finds an appropriate alignment between them (shown by the dotted diagonal lines). This invariance to timing differences allows the clustering algorithm to easily compare cases where the onset of a high arousal state is fast and immediate to cases where the onset is slower or less proximal to the active measurement occasion. Algorithms have been developed to allow extremely fast DTW comparisons against very large datasets [36].

Fig. 2.

An example alignment using DTW. The two curves shown in red and black are of different length and phase, but the algorithm finds a reasonable alignment [16]

Feature-Based Binary Classification via the Decision Tree Ensembles (“Random Forests”)

In order to study which characteristics of a time series are important for classification accuracy, we also employed a feature-based machine learning method that first extracted features of the time series and then used them for classification. These features may represent either global (e.g., grand mean) or local (e.g., level at time t) characteristics of the time series. Such features can be straightforward (e.g., the maximum/minimum of the time series), or can be more complex, such as specific wavelet transform coefficients. Similarly, they can be almost always either global, as in the case of maximum/minimum, or structured around a specific time point, like a wavelet coefficient. They therefore stand in contrast to the DTW distance, which is both global and timing-invariant. After features are extracted, they then become the input given to the classifier in lieu of the raw time-series data.

We used the python package tsfresh to extract approximately 70 base features from each time series [12]. These features range from simple measures such as minimum, maximum, variance, and autocorrelation to count-based measures such as the number of measurements above or below the mean to more intricate features such as approximate entropy, frequency domain measures such as power spectrum density, and time-frequency measures such as wavelet transform coefficients. Several of these features are computed over different time windows relative to the outcome, resulting in around 700 overall features. See the tsfresh documentation for details [11].

A decision tree classifier, such as a CART [6], is a simplistic classifier which attempts to find a series of simple binary conditions (e.g., Is mean heart rate > 100 bpm in the window?) that are most predictive of a given outcome. By combining a series of these conditions into a tree, it is possible to capture arbitrarily complex interactions among the predictors. Typically, the selection of decision criteria is performed using a brute-force approach by searching a large number of features and potential split points, and therefore have a strong tendency to overfit data sets.

Ensembles of decision trees, also called random forests, consist of a large number of decision trees, typically created using a training algorithm called bootstrap aggregation (bagging). Given a dataset of size N, this is done by creating a large number of bootstrap samples of size N by randomly sampling observations with replacement. Each such sample is then used to train a decision tree classifier, while also sampling features to use while building the tree. The random forests algorithm then combines the predictions of these many decision trees using majority vote. The introduction of randomness into both the data selection and feature selection acts as a regularization method, reducing the tendency of decision trees to overfit. According to its inventors, random forests do not require much fine-tuning of parameters; the default parameterization often leads to excellent performance [7]. They are also robust to the presence of noise in the predictors. In early testing, random forests on our datasets outperformed all other feature-based algorithms such as support vector machines (SVM), despite our efforts at kernel selection, tuning, and feature selection.

Random forests also provide an inherent measure of feature importance—that is, they allow us to quantify how much benefit a given feature provides to the predictive model. For each tree (and bootstrap sample), the algorithm would exclude some observations from the original dataset, called “out-of-bag” (OOB) observations. These out-of-bag observations function as a type of test dataset. After fitting, the algorithm ranks a feature by comparing accuracy in the out-of-bag data before and after randomizing the values of the feature in the OOB data. A larger drop in accuracy results in a higher importance score. This measure allows us to rank the features by how helpful they are in predicting high arousal for a specific individual.

We note that non-linear dependence on previous data points is a concern when working with time-series data. State space models are commonly used to address this issue, for example Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) have been applied to child behavior (e.g., [40, 43]). Our two methods use two different ways to deal with non-linearity. Tsfresh decomposes the time series, then the random forest learns complex decision boundaries in a piecewise linear form. DTW “warps” sequences non-linearly to determine a measure of their similarity independent of certain non-linear variations in the time dimension. Furthermore, kNN is in general a non-linear classifier because the shape of the decision boundary is determined by the data.

Other approaches such as Dynamic Bayesian Network or Hidden Markov Models might be able to accommodate time-series non-linearity in a more optimal manner (depending on the dataset); however, these are more complex from a user perspective and have higher data and computational requirements.

Method of Evaluation

As mentioned earlier, we used the caret package (version 6.0-76) to run the classifiers [26]. Caret is automatically set to call the randomForest package (version 4.6-12). Since to the best of our knowledge there is no appropriate implementation of k-NN using DTW distance in R, we wrote a custom model within caret. Our custom model uses the RUCRDTW R package [36] for efficient DTW matching of sequences.

Both sets of classifiers require the choice of tuning parameters that influence their function, for example k for k-nearest neighbors or the number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split for random forests. These tuning parameters were determined using cross-validated grid search, the default search process in R’s caret package. Though as discussed earlier, random forests did not seem to benefit much from tuning. We set the number of trees at 5000.

When a fitted classifier is applied to a new time series, the classifier reports a probability that the time-series sequence represents a high arousal state for a certain individual. A probability threshold could then be used to determine whether to deliver an intervention in response to this time series; that is, we might act if the probability was over 75%. In an ambulatory setting, this threshold would likely be specifically and adaptively selected for the specific user, classifier, and context, based on some estimation function for the cost (in terms of monetary costs, participant burden, user trust, etc.) of a falsely deployed intervention compared with the cost of a missed event. For example, if the state detection resulted in a phone notification that could be easily ignored by the user, one might send out the notification any time the probability rose above 50%, balancing the rate of false positives with the rate of false negatives. On the other hand, for a costlier and/or invasive response (e.g., a visit by a care provider in the case of a user in drug addiction recovery), one might require a higher threshold, allowing more false negatives to lower the rate of false positive responses. The trade-off between false positives and false negatives at different levels of threshold can be captured in a plot called a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) provides a measure of accuracy across all possible thresholds. The value of AUC can be interpreted as the probability that a classifier will correctly rank a randomly chosen positive example as more likely to be positive than it would a randomly chosen negative one. The larger the AUC, the better the discrimination between the two classes. This measure is useful for comparing models because it gives a concise summary of the classifier’s performance over a range of thresholds.

Model Specifications

Three types of binary classification models were explored in this paper, described below.

Type 1. Individual-specific models with only one data stream. For each individual, we found their 40 extreme arousal values, then extracted 15 prior minutes of ACC, BVP, EDA, and TEMP data. Each predictor matrix used in RF had 40 rows (data points) and approximately 700 columns (features). The response is a vector of 20 “High” values and 20 “Low” values. We fit the binary classifiers RF and k-NN on the ACC, BVP, EDA, and TEMP data separately, getting eight AUC values for each individual. Note that k-NN uses only the raw data.

Type 2. Multiple-predictor Individual-specific models. For each individual, we combined their extreme ACC, BVP, EDA, and TEMP data into one matrix via their columns. Each predictor matrix had 40 rows (data points) and approximately 800 columns (features). After fitting the models, we end up with one AUC value for each individual. We only used RF-based classification, as RF previously performed just as well as k-NN in Type 1 models and had the added advantage that we could look at feature importance.

Type 3. Between-person models using all four data streams combined. We used a leave-two-out strategy during training, that is we trained the model using 10-fold cross validation on 23 randomly chosen people’s combined data and evaluated it on the last two peoples’ data. The predictor matrix had 23 ∗ 40 rows (data points) with 2800–3500 columns, and the response vector had the associated 23 ∗ 20 “High” values, and 23 ∗ 20 “Low” values. This leave-two-out strategy was repeated 25 times, and we end up with 25 AUC values.

To train each model, we first divided the dataset into training and test sets, using a 90-10 split. With Type 1 and Type 2 models, we started out with 40 data points in the model, so the test set had 4 points. With Type 3 models, we started out with 25 people so we used a leave-two-out strategy to form the test set. We then used 10-fold cross validation on the remaining data (training set) to tune the algorithms and get the hyperparameters. Cross validation, commonly used to avoid overfitting, is performed by repeatedly splitting the dataset into 10 parts, training the algorithm on 9/10ths of the data, then evaluating it on the remaining 1/10th to find optimal hyperparameters. Final performance measures were found by evaluating the final model (with parameters optimized from 10-fold cross validation) on the test set. This process is designed to better estimate the algorithm’s ability to generalize to unseen data. Without this there is a risk of overfitting, that is the algorithm might essentially memorize specific quirks of the dataset and reproduce them during testing for an inflated performance measure.

In addition to getting the AUCs above, we also ran comparisons between models. For the Type 1 individual-specific models described above, we compared performance under k-NN and RF. After getting AUCs for all individuals under each of the four data streams, we ran four paired t tests to compare the AUCs of k-NN and RF on an individual basis. We also compared the performance of individual-specific multi-datastream models (Type 2 above) and a one-size-fits-all between-person model (Type 3 above). This analysis was done by using the RF algorithm to get AUCs for both models, then comparing the models using paired t tests on the AUCs. The between-person model trades additional variability (that is, between-person variability) for more data. The individual model, in comparison, has only a given individual’s fraction of data, but contains only within-person variability. This comparison can help us understand how important individualized models are for accurate prediction of psychological states. In practice we may not have any data on a new individual, therefore we would rely on the between-person models for prediction.

Results

In Fig. 3, we display boxplots of the AUCs from Type 1, 2, and 3 models. The left section of Fig. 3, titled “One data stream,” shows the AUC summary statistics over the 25 individuals for the Type 1 models, with their associated datastreams on the x-axis. We see that when looking at one datastream at a time and building individual-specific models, random forests largely outperform k-NN. The median AUCs for the four RF individual-specific models ACC, BVP, EDA, and TEMP are (0.625,0.703,0.625,0.679), respectively, while the median AUCs for k-NN are (0.593,0.617,0.570,0.61), respectively. Paired t test at α = .05 showed significant differences between the two methods for heart rate (BVP; p = 0.0023), electrodermal activity (EDA; p = 0.01), and temperature (TEMP; p = 0.013 ), but not for acceleration (ACC; p = 0.33).

Fig. 3.

We compare multiple models according to how well they distinguish high and low arousal states. The left section titled “One data stream” shows results on comparing the efficiency of k-nearest neighbor and random forests in terms of AUC scores (Type 1). Each boxplot here summarizes the distribution of AUC values found from fitting a model over the 25 individuals. The x-axis shows the physiological data streams used to predict low and high arousal states. The right-hand side section titled “Multiple data stream” shows the AUCs for the between-person random forests classifier (Type 3) versus the individual-specific random forests classifier (Type 2), where both use all four of the predictor data streams

We also compared the performance of Type 2 (individual-specific) and Type 3 (between-person) models, plotted at the right-hand section of Fig. 3, titled “Multiple data streams.” The performance of the individual-specific model was better than the between-person model (median AUC 0.75 versus 0.66; p = 0.043), likely because of the advantages of taking individual-specific characteristics into account.

The Supplementary Materials contain further supporting analyses, such as ROC curves, Positive Predictive Values (PPV), and Negative Predictive Values (NPV) for the various Arousal models. We also examine two other outcomes—Felt Love and Valence—and find similar results: RF is slightly better than k-NN, multiple predictor models are at least as good as single predictor models, and individual models are better than between-person models.

Comparing Type 2 and Type 3 Models Using Feature Importance

We extracted feature importance scores in the Type 2 (individual-specific multi-datastream) models and Type 3 (between-person) models to compare the most predictive set of features across the two model types. Figure 4 (column 1) shows feature importance for the top 20 features in the between-person model, and the importance of those features in the individual-specific models for three different individuals (columns 2–4). As can be seen, the most predictive set of features in the between-person model do not systematically correspond to important features in the individual-specific models, suggesting a possible explanation for why the individual-specific models outperform the between-person model. To further illustrate the feature importance discrepancies, in Fig. 5, we calculate rank correlation between the between-person feature importance list and each of the individual-specific feature importances. With the median correlation of 0.04, we find no overall agreement between the two types of models.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of feature importance between between-person model and individual-specific models. The top 15 features from the between-person model are shown; the rows in the table are ordered by the feature importance in the between-person model. Features were obtained from tsfresh, see the documentation for details [11]

Fig. 5.

Histogram of rank correlations between feature importances of each of the 25 individual models and feature importances of the between-person model

Conclusion and Future Work

After 4 weeks of data collection, we find ourselves with a reasonable ability to differentiate between high and low states of arousal self-reports using physiological data from a wearable device. We note, however, that the generalizability of the findings is limited because the sample size was relatively low (only 25 people) and not diverse (it mostly consisted of Caucasian participants).

Our results show that there is considerable variation among individuals. Predicting arousal using random forests achieved an AUC as high as 1, and as low as 0.3. These individual differences in predictive performance might stem from individual differences in the concordance between physiological and reported arousal, meaning some people’s physiological data might naturally contain more information for the machine learning tools to work with. Researchers have long known that there are individual differences in participants’ physiological responses [25, 27] and this, alongside differences in context and logistical factors (e.g., some participants may have worn the wristband incorrectly), may be contributing to these inter-individual differences in prediction accuracy.

We find that the random forests classifier outperforms the k-NN approach in the individual models. Although the situation might change if we had more data (e.g., k-NN might work better with more data), for the setting we had in mind, the current 4 week-long data collection already posed considerable participant burden. Generally EMA studies with several self-reports each day do not run longer than 4 weeks, as after this participant compliance rate drops. Thus, it is not reasonable to assume that we can collect more classified target states per individual to train the algorithms without significant changes to the data collection process. Nevertheless, these data provide initial evidence that the random forests algorithm may be particularly useful for training individual-specific classifiers on physiology data collected in real-life studies.

In our study, individualized models using all the data streams performed better than between-person models. In the individualized models for each person, only 32 target states (we had 40 altogether but 4 were used in cross validation, and 4 were left out for final testing) were used for training the random forests algorithm. In the between-person models, we had much more data for training the classifier: we could use 23 ∗ 36 target states for training, 23 ∗ 2 data points for cross validation, then the 24th and 25th peoples’ data (2 ∗ 40 target states) was the evaluation set. We note, however, that we had a relatively small sample of heterogeneous persons. In the individual-specific model, the 32 target states directly applied to the particular person’s psychophysiological dynamics, as opposed to the between-person model which used other people’s data to draw conclusions regarding an “unseen” individual. The results showed that the smaller but more focused dataset specific to the individual yielded higher prediction accuracy than a larger data set containing additional between-person variability. Post hoc exploration of feature importance provided a possible explanation for this gap in performance by showing how the most predictive features differed across people, and that the individual-specific feature sets differed from the most important features of the between-person model.

Taken together, these findings show a consistent pattern: at least based on this wearable physiology sensor, individuals can differ greatly in their physiological correlates of psychological states in everyday life. Compared with the ground-truth standard (for psychological states) of self-report, we find that it is possible to model an individual’s psychological state from their physiology, but the manner in which psychological state is predicted, even down to the level of which physiological predictors are most important, may vary greatly from person to person.

Building on the current findings, potential future work can take several directions. First, we limited our testing to binary classification of arousal; that is our focus was on distinguishing high from low arousal states. Predicting whether an individual is in a low or high arousal state might be an important piece of information in intervention settings, for example in order to optimize timing of ambulatory interventions. However, a more nuanced approach might separate high, neutral and low arousal states, for example to deliver interventions tailored to such states, and to explore the limits of individualized models, or use cluster analysis to discover natural groupings. Second, while we only focused on predicting self-reported arousal from physiology signals, there are certainly other psychological states for which a combination of physiological markers could be predictive. Future studies might want to do thorough exploration of different self-reported measures as outcomes and EDA, heart rate, activity and body temperature as predictors. For exploratory purposes, we re-ran the analysis with the Valence (“How pleasant do you feel right now?”) and Felt Love (“How much do you feel loved right now?”) levels as outcomes in place of Arousal. The prediction accuracy tended to be smaller overall for these outcomes, with some Type 1 models showing large variations in AUC values across people; please see details in the Supplementary Materials.

Also, future work should look into improving accuracy by finding sensors and feature transforms that better maintain their predictive power across individuals. An alternative direction would be to seek out ways to automatically customize an individual model by leveraging between-person information, for example via hierarchical modeling, or through the use of covariate information such as age and gender. Additional work incorporating dynamical models, such as hidden Markov models, might also provide a path forward to improve individualized modeling of psychological states from physiology.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Computations for this research were performed on the Pennsylvania State University’s Institute for CyberScience Advanced CyberInfrastructure (ICS-ACI).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berndt DJ, Clifford J (1994) Using dynamic time warping to find patterns in time series. In: KDD workshop, Seattle, WA, vol 10, pp 359–370

- 2.Bezawada S, Hu Q, Gray A, Brick T, Tucker C. Automatic facial feature extraction for predicting designers’ comfort with engineering equipment during prototype creation. J Mech Des. 2017;139(2):021102. doi: 10.1115/1.4035428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boker SM, Cohn JF, Theobald BJ, Matthews I, Mangini M, Spies JR, Ambadar Z, Brick T. Something in the way we move: motion dynamics, not perceived sex, influence head movements in conversation. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2011;37(2):631–640. doi: 10.1037/a0021928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bond DS, Thomas JG, Raynor HA, Moon J, Sieling J, Trautvetter J, Leblond T, Wing RR. B-mobile - a smartphone-based intervention to reduce sedentary time in overweight/obese individuals: a within-subjects experimental trial. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(6):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braithwaite JJ, Watson DG, Jones R, Rowe M. A guide for analysing electrodermal activity (EDA) & skin conductance responses (SCRs) for psychological experiments. Psychophysiology. 2013;49(1):1017–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brick T, Gray A, Staples AD (2017) Recurrence quantification for the analysis of coupled processes in aging. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Brick T, Hunter MD, Cohn JF (2009) Get the FACS fast: automated FACS face analysis benefits from the addition of velocity. In: 3rd International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction and Workshops, 2009. ACII 2009. IEEE, pp 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Brick T, Koffer RE, Gerstorf D, Ram N (2017) Feature selection methods for optimal design of studies for developmental inquiry. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Christ M, Braun N, Neuffer J Tsfresh documentation. https://tsfresh.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- 12.Christ M, Kempa-Liehr AW, Feindt M (2016) Distributed and parallel time series feature extraction for industrial big data applications. arXiv:1610.07717

- 13.Ding H, Trajcevski G, Scheuermann P, Wang X, Keogh E. Querying and mining of time series data: experimental comparison of representations and distance measures. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment. 2008;1(2):1542–1552. doi: 10.14778/1454159.1454226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang SY, Zinszer B, Malt B, Li P (2015) A computational model of bilingual semantic convergence. Cognitive Science Society

- 15.Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, Patel V, Haines A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLOS Medicine. 2013;10(1):1–45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giorgino T, et al. Computing and visualizing dynamic time warping alignments in R: the dtw package. J Stat Soft. 2009;31(7):1–24. doi: 10.18637/jss.v031.i07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao T, Chang H, Ball M, Lin K, Zhu X. cHRV uncovering daily stress dynamics using bio-signal from consumer wearables. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2017;245:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Brit J Health Psychol. 2010;15(1):1–39. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hovsepian K, Al’absi M, Ertin E, Kamarck T, Nakajima M, Kumar S (2015) Cstress: Towards a gold standard for continuous stress assessment in the mobile environment. In: UbiComp 2015 - Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, UbiComp 2015 - Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, 493–504, Association for Computing Machinery, Inc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Hovsepian K, al’Absi M, Ertin E, Kamarck T, Nakajima M, Kumar S. cStress: towards a gold standard for continuous stress assessment in the mobile environment. Proceedings of the... ACM International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing. UbiComp (Conference) 2015;2015:493–504. doi: 10.1145/2750858.2807526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Q, Bezawada S, Gray A, Tucker C, Brick T (2016) Exploring the link between task complexity and students’ affective states during engineering laboratory activities. In: ASME 2016 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, pp V003T04A019–V003T04A019

- 22.Karch JD, Sander MC, von Oertzen T, Brandmaier AM, Werkle-Bergner M. Using within-subject pattern classification to understand lifespan age differences in oscillatory mechanisms of working memory selection and maintenance. Neuroimage. 2015;118:538–552. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller J, Bless H, Blomann F, Kleinböhl D. Physiological aspects of flow experiences: skills-demand-compatibility effects on heart rate variability and salivary cortisol. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2011;47(4):849–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keogh E, Pazzani MJ (2000) Scaling up dynamic time warping for datamining applications. In: Proceedings of the Sixth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. ACM, pp 285–289

- 25.Koriat A, Averill JR, Malmstrom EJ. Individual differences in habituation: some methodological and conceptual issues. J Res Personality. 1973;7(1):88–101. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(73)90035-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhn M, et al. Caret package. J Statist Softw. 2008;28(5):1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v028.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacey JI, Lacey BC. Verification and extension of the principle of autonomic response-stereotypy. Am J Psychol. 1958;71(1):50–73. doi: 10.2307/1419197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews M, Abdullah S, Murnane E, Voida S, Choudhury T, Gay G, Frank E. Development and evaluation of a smartphone-based measure of social rhythms for bipolar disorder. Assessment. 2016;23(4):472–483. doi: 10.1177/1073191116656794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molenaar PCM. A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives. 2004;2(4):201–218. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muessig KE, Pike EC, LeGrand S, Hightow-Weidman LB. Mobile phone applications for the care and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases: a review. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murnane EL, Abdullah S, Matthews M, Kay M, Kientz JA, Choudhury T, Gay G, Cosley D (2016) Mobile manifestations of alertness. In: The 18th International Conference. ACM Press, New York, pp 465–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Nahum-Shani S, Smith SN, Tewari A, Witkiewitz K, Collins LM, Spring BJ, Murphy SA (2014) Just-in-time adaptive interventions (jitais): an organizing framework for ongoing health behavior support. Tech. rep., Penn State [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Picard RW (2015) Recognizing stress, engagement, and positive emotion. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, IUI ’15. ACM, New York, pp 3–4, DOI 10.1145/2678025.2700999, (to appear in print)

- 34.Picard RW, Fedor S, Ayzenberg Y (2015) Multiple arousal theory and daily-life electrodermal activity asymmetry. Emotion Review: 1–14. 10.1177/1754073914565517, http://emr.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/02/20/1754073914565517

- 35.Posada-Quintero HF, Florian JP, Orjuela-Cañón AD, Chon KH. Electrodermal activity is sensitive to cognitive stress under water. Front Physiol. 2018;8:1128. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rakthanmanon T, Campana B, Mueen A, Batista G, Westover B, Zhu Q, Zakaria J, Keogh E (2012) Searching and mining trillions of time series subsequences under dynamic time warping. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. ACM, pp 262–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Ram N, Benson L, Brick T, Conroy DE, Pincus AL (2016) Behavioral landscapes and earth mover’s distance. A new approach for studying individual differences in density distributions. Journal of Research in Personality [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ramseyer F (2014) Nonverbal synchrony of head- and body-movement in psychotherapy: different signals have different associations with outcome. Front Psychol: 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Russell JA, Barrett LF. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: dissecting the elephant. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76:805–819. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shewark EA, Brick T, Buss KA Capturing temporal dynamics of fear behaviors on a second by second basis (in prep) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Smyth H (2016) Is providing mobile interventions “just-in-time” helpful? An experimental proof of concept study of just-in-time intervention for stress management. In: 2016 IEEE wireless health (WH), pp 1–7, DOI 10.1109/WH.2016.7764561, (to appear in print)

- 42.Smyth JM, Juth V, Ma J, Sliwinski M A slice of life: ecologically valid methods for research on social relationships and health across the life span. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 11(10):e12356. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/spc3.12356. E12356 SPCO-0823.R1

- 43.Stifter CA, Rovine M. Modeling dyadic processes using hidden Markov models: a time series approach to mother–infant interactions during infant immunization. Infant and Child Development. 2015;24(3):298–321. doi: 10.1002/icd.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Ann Behav Med. 1994;16(3):199–202. doi: 10.1093/abm/16.3.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuarob S, Tucker CS, Kumara S, Giles CL, Pincus AL, Conroy DE, Ram N. How are you feeling?: A personalized methodology for predicting mental states from temporally observable physical and behavioral information. J Biomed Inform. 2017;68:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeykelis L, Cummings JJ, Reeves B. Multitasking on a single device: arousal and the frequency, anticipation, and prediction of switching between media content on a computer. J Commun. 2014;64(1):167–192. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu D, Yi X, Wang Y, Lee KM, Guo J. A mobile sensing system for structural health monitoring: design and validation. Smart Materials and Structure. 2010;195:055011–12. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/19/5/055011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.