Abstract

Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease that can be found worldwide. Although it has been eradicated and is under control in most developed countries, it still represents an important health problem in many parts of the world. In this case report, we present a rare unusual findings of a case with panuveitis uveitis secondary to brucellosis.

Keywords: Brucellosis, infectious zoonotic disease, unpasteurized raw milk, uveitis

INTRODUCTION

Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease that can be found worldwide. Although it has been eradicated and is under control in most developed countries, it still represents an important health problem in many parts of the world, including the Middle East, the Mediterranean, Mexico, and Central and South America.[1,2,3] Brucellosis, also known as Malta fever, undulant fever, or Mediterranean fever, is a systemic infectious disease that is transmitted to humans through the ingestion of the unpasteurized or raw milk and cheese of animals infected with Brucella organisms (e.g., sheep, cattle, camels, pigs, and dogs) or through contact with infected animals. Ingestion of the undercooked meat of infected animals is an uncommon route of transmission.[4]

Although KSA is a country that has undergone rapid modernization over the past 40 years, maintaining traditions remains important. The combination of the modern and the traditional is a hallmark of Saudi Arabian life. Raising camels is an essential part of the history of KSA. Camel owners are proud to have them and take care of their dynasties. Furthermore, they derive many benefits from camels including the consumption of their milk and meat. Those who own and tend to camels usually prefer to drink unpasteurized camel milk, when it is frothy and warm, directly after squeezing it from the animal. Passersby also commonly enjoy camel milk, preferring to get it fresh directly from shepherds. People who live in rural areas often raise sheep and goats and serve their unpasteurized milk to guests.[5]

In KSA, higher incidences of brucellosis have been reported in Al-Qassim, Aseer, Hail, Northern Borders, and Najran. Those aged 15–44 years old had the highest prevalence of brucellosis.[6]

Brucellosis is a multisystem disease that may present with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations. Complications of this disease can affect almost all organs and systems with varying incidence. The disease may be acute or chronic. The main symptoms are fever, chills, sweating, headache, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, anorexia, weight loss, splenomegaly, and diffuse lymphadenopathy. Organ involvement of the lung, bone, kidney, central nervous system, heart, and eye occurs in about 10%–15% of cases.[3,7,8,9,10,11]

The eye involvement in brucellosis occurs in different forms including dacryoadenitis, conjunctivitis, episcleritis, keratitis, iritis, iridocyclitis, neuroretinitis, retinitis, choroiditis, panuveitis, pars planitis, and hyalitis. The clinical manifestations of ophthalmic brucellosis include injection, blurred vision, eye pain, tearing, diplopia, foreign-body sensation, cotton-wool lesions, exudative retinal detachment, and retinal hemorrhage.[12,13,14,15,16]

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old healthy female, from Hail city, presented to the ophthalmic emergency department complaining of bilateral photophobia and pain, both with onset 2 months prior. She has a history of bilateral knee pain, malaise, fever, and upper respiratory infection that complains start 3 weeks after she consuming unpasteurized milk. At that time, she was admitted to a general hospital and placed on an intravenous antibiotic for 9 days. A systemic review indicated a positive history of raw milk consumption, positive history of sporadic knee pain with no stiffness, a positive history of multiple skin papules, no back pain, no history of contact with tuberculosis patients, no history of tuberculosis in the family, no history of oral or genital ulcer, no history of shortness of breath or cough, no history of night sweats, no history of weight loss, no history of tinnitus or hearing problems, no history of gastrointestinal problems, and no history of limb numbness.

On examination, the visual acuity was 20/100 right eye (OD) and 20/400 left eye (OS), intraocular pressure was 12 mmHg bilaterally, and lid and conjunctiva were within normal limits bilaterally. The cornea shows fine keratic precipitate in both eyes, there were multiple posterior synechiae with no nodules bilaterally, and the anterior chamber was deep with 2+ cells bilaterally. The lens was clear in both eyes. Ophthalmoscopy of the OD indicated a flat retina, mild disc swelling nasally, severe anterior vitreous cell, macular edema with no snowbanks or snowballs, and no retinitis or vasculitis. Ophthalmoscopy of the OS indicated a flat retina, mild disc swelling, severe anterior vitreous cell, macular edema, no snowbanks or snowballs, and no retinitis or vasculitis.

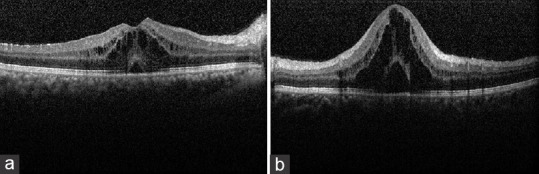

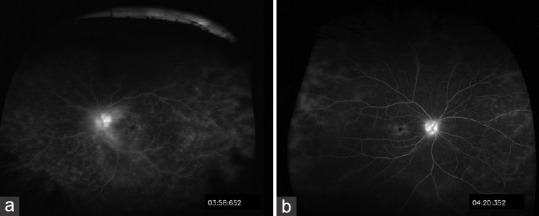

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) indicated macular edema with intra- and subretinal fluid that was greater in the OS compared to the OD and choroidal thickening in the OS [Figure 1a and b]. Fundus fluorescein angiography indicated hyperemic disc and multiple areas with diffuse pinpoint hyperfluorescence with late leakage in both eyes [Figure 2]. Magnetic resonance imaging was normal, with no signs of multiple sclerosis. Complete blood count, liver function test, and renal function test were normal. The following tests were requested, and the results were negative for purified protein derivative (PPD), venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and antitoxoplasma Ab (IgM and IgG). Chest computed tomography was normal. The patient was started on topical prednisolone four times daily, atropine three times daily until we ruled out tuberculosis.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Optical coherence tomography of both eyes at presentation of a patient with brucellosis shows central involvement macular edema with fluid accumulation intra-retinal at outer plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, as well as subretinal

Figure 2.

(a and b) Fundus fluorescein angiography both eye at presentation of a patient with brucellosis shows bilateral hyperfluorescence optic disc, and late leaks at macular area both eye, with characteristic flower petal appearance right eye

Three days later, PPD was negative. Then, we suspected brucellosis based on the clinic manifestation and history of unpasteurized milk despite a negative serology result for Brucella (Brucella total antibody was 1:80 and Brucella IgG antibody <1:20), which well known of lack specificity and provide results that may be difficult to interpret in individuals repeatedly exposed to Brucella organisms and we consulted an infectious disease specialist. Due to patient symptoms that were consistent with brucellosis and a fever, the infectious disease specialist advised us to start the patient on a course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral rifampicin 300 mg twice daily for 6 weeks with no systemic steroid.

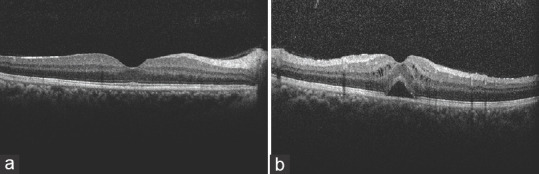

Three weeks later. At follow-up, the vision was 20/40 OD and 20/160 OS, and intraocular pressure was 13 mmHg bilaterally. All systemic and ocular symptoms of the patient were resolved; on slit-lamp examination, the lid and conjunctiva were within normal limits bilaterally. The cornea shows resolved the keratic precipitate in both eyes, there were few posterior synechiae with no nodules bilaterally, and the anterior chamber was deep and quit bilaterally. The lens was clear in both eyes. Ophthalmoscopy of both eye indicated a clear vitreous, flat retina, normal optic disc, no vasculitis, and no retinitis. OCT showed a dramatic decrease in macular edema bilaterally [Figure 3a and b].

Figure 3.

Optical coherence tomography after 3 weeks of treatment for brucellosis (a and b) shows resolved macular edema in one eye and improve macular edema in another eye

DISCUSSION

Ocular complications of brucellosis include most commonly, cataracts, followed by vitreal alterations, phthisis bulbi, maculopathies, glaucoma, neovascular retinal membrane, tractional retinal detachment, and other less frequent complications.[13] Rolando et al.[17] reported that the most frequent uveal syndrome was posterior uveitis, followed by panuveitis. They[17] found that 9 (35%) of 25 patients with brucellosis had posterior uveitis (35%) and 8 (32%) had panuveitis. The current case indicates that brucellosis remains an important health problem in many developing countries and some patients with brucellosis may present with uveitis which is treatable.

We initially suspected an infectious uveitis, and a systemic workup was performed to rule out brucellosis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, and syphilis. These laboratory tests were negative. Hence, the history and unusual ocular presentation we suspected brucellosis. At 3-week follow-up after beginning treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral rifampicin 300 mg twice daily, vision and ocular sign dramatically improved. Brucellosis should be considered in patients who consumed unpasteurized milk and live in the endemic area despite negative Brucella total antibody was and Brucella IgG antibody results, which well known of lack specificity and provide results that may be difficult to interpret in individuals repeatedly exposed to Brucella organisms.[18]

CONCLUSION

A young patient presented with bilateral panuveitis uveitis, and history and ophthalmic findings suggested brucellosis. The patient improved dramatically during treatment with doxycycline and rifampicin.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young EJ. Brucella species. In: Mandell GL, Bennet GE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 2386–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karapinar B, Yilmaz D, Vardar F, Demircioglu O, Aydinok Y. Unusual presentation of brucellosis in a child: Acute blindness. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:378–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb03085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbel MJ. Brucellosis: An overview. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:213–21. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brucellosis USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Last accessed on 2012 March 31]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: http://www. cdc.gov/brucellosis/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali I. Saudi Arabia: Asharq Al Awsat: The Leading Arabic International Paper; 2004. Jan 14, Directed to Focus on the Importation of Frozen Meat and Refrigerated. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aloufia AD, Memishab ZA, Assiriab AM, McNabbb SJ. Trends of reported human cases of brucellosis, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2004–2012. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2016;6:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young EJ. Brucella species. In: Mandel GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 2671–2. Part 3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall WH. Brucellosis. In: Evans AS, Brachman PS, editors. Bacterial Infections in Humans. New York, NY: Plenum; 1991. pp. 133–49. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grave W, Sturm AW. Brucellosis associated with a beauty parlour. Lancet. 1983;1:1326–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraunfelder FT, Roy FH, Randall J. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. Current Ocular Therapy 5; pp. 15–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gür A, Geyik MF, Dikici B, Nas K, Cevik R, Sarac J, et al. Complications of brucellosis in different age groups: A study of 283 cases in southeastern Anatolia of Turkey. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44:33–44. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2003.44.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatipoglu CA, Yetkin A, Ertem GT, Tulek N. Unusual clinical presentation of brucellosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:694–7. doi: 10.1080/00365540410017554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolando I, Olarte L, Vilchez G, Lluncor M, Otero L, Paris M, et al. Ocular manifestations associated with brucellosis: A 26 – year experience in Peru. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1338–45. doi: 10.1086/529442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puig Solanes M, Heatley J, Arenas F, Guerrero Ibrra G. Ocular complications in brucellosis. Am J ophthalmol. 1953;36:675–89. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(53)90310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabinowitz R, Schneck M, Levy J, Lifshitz T. Bilateral multifocal choroiditis with serous retinal detachment in a patient with Brucella infection: Case report and review of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:116–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moutray TN, Williams MA, Best RM, McGinnity GF. Brucellosis: A forgotten cause of uveitis? Asian J Ophthalmol. 2007;9:30–1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolando I, Tobaru L, Hinostroza S, Guerra L, Carbone A, Carrillo C, Gotuzzo E. Clinical manifestations of brucellar uveitis. Ophthalmil Practice. 1987;5:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yagupsky P, Morata P, Colmenero JD. Laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:e00073–19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00073-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]