Abstract

Amid the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19), the scientific community has a responsibility to provide accessible public health resources within their communities. Wastewater based epidemiology (WBE) has been used to monitor community spread of the pandemic. The goal of this review was to evaluate the need for an environmental justice approach for COVID-19 WBE starting with the state of California in the United States. Methods included a review of the peer-reviewed literature, government-provided data, and news stories. As of June 2021, there were twelve universities, nine public dashboards, and 48 of 384 wastewater treatment plants monitoring wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 within California. The majority of wastewater monitoring in California has been conducted in the urban areas of Coastal and Southern California (34/48), with a lack of monitoring in more rural areas of Central (10/48) and Northern California (4/48). Similar to the access to COVID-19 clinical testing and vaccinations, there is a disparity in access to wastewater testing which can often provide an early warning system to outbreaks. This research demonstrates the need for an environmental justice approach and equity considerations when determining locations for environmental monitoring.

Keywords: Equity, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Public health, Environmental surveillance, Geospatial analysis

Introduction

Equitable access to environmental and public health resources is needed for the fairness and advancement of all groups. Both rural [1,2] and urban communities in the U.S [3,4]. experience COVID-19 disparities. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) published a report revealing populations at risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity on July 16, 2021 [5]. Black or African American communities were 1.1 times at risk of contraction [6], 2.8 times at risk of hospitalization [7], and 2.0 times at risk for death [8]. American Indian or Alaska Native populations resulted in 1.7 times at risk of contraction [6], 3.4 times at risk of hospitalization [7], and 2.4 times at risk of death [8]. Hispanic/Latino communities were 1.9 times at risk of contraction [6], 2.8 times at risk of hospitalization [7], and 2.3 times at risk of death [8].

To further understand community transmission, scientists have turned to wastewater based epidemiology (WBE) [9]. WBE involves the examination of wastewater for traces of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, the virus that causes the COVID-19 disease, to analyze the prevalence of community viral load. WBE can serve as a lower cost tool to support individual testing in communities [10], and optimize resources within a specific testing site, such as a university campus [11]. One wastewater sample can represent the disease burden of hundreds and even millions of people depending on the location of the wastewater treatment sample (treatment facilities, pumping stations, manholes, and other sewer locations), and thus allow for more widespread, equitable, and less invasive testing [12]. Despite this ability, wastewater monitoring has not been deployed equitably globally, but primarily in high income countries like the U.S. [13]. Even within the U.S. there may be testing disparities similar to access to clinical testing and vaccinations [14].

The purpose of this review of California WBE efforts is to assess the need for an environmental justice approach to COVID-19 monitoring efforts. Environmental justice [15] is defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as “… the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies”. The pandemic has shed light on areas that need improvement within the nation's public health systems in both rural and urban communities. Equity of wastewater monitoring efforts for SARS-CoV-2 is a principal component to consider.

An environmental justice evaluation of California's COVID-19 wastewater monitoring efforts

The COVIDPoops19 framework for the State of California

The COVIDPoops19 global dashboard was created in 2020 from publicly-accessible data from six different data sources (literature searches, the COVID-19 WBE website, webinars, Google Form submissions, Twitter keyword searches, and Google keyword searches) [13]. The dashboard serves as a compilation of monitoring efforts of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater to aid researchers and the public to identify where testing is occurring in their area. COVIDPoops19 literature and news sources were filtered on June 8, 2021 for this review.

After filtering the COVIDPoops19 dashboard data for the state of California, the site names, along with the corresponding latitude and longitude were extracted for each location. The data was then uploaded to ArcGIS Online as individual points portraying the known wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in California [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23], the sites (universities and WWTPs) monitoring their wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39], and public dashboards [29] that display COVID-19 wastewater data.

In the state of California in June 2021, there were 384 wastewater treatment facilities and 48 (12.5%) of those facilities monitor SARS-CoV-2 in their influent wastewater [40]. There were 12 known universities publishing WBE efforts from their campuses and communities, along with nine public dashboards throughout the state displaying their public health efforts through wastewater monitoring in their local facilities.

Urban and rural review

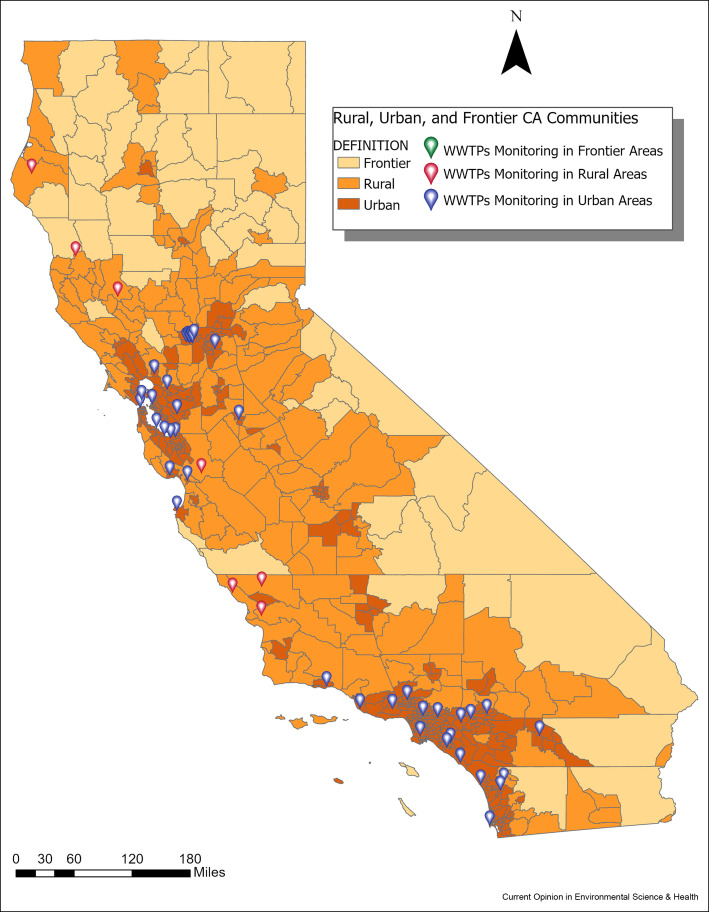

A key component of equity is access for both rural and urban areas. Rural areas often lack access to health care and education resources [41]. In addition, rural areas typically consist of smaller treatment plants spread out between communities compared to urban areas, and this provides economic and logistical challenges to wastewater monitoring [42]. Initially rural areas were not hard hit by COVID-19 potentially due to the lower population densities, but eventually the pandemic spread to many of these areas and overloaded their limited hospital capacities [43]. Figure 1 displays the map of WWTPs in rural, urban, and frontier communities in California and those monitoring SARS-CoV-2 [46]. From the three layers, urban communities in California currently comprise 41 out of the 48 (85%) total WWTPs monitoring SARS-CoV-2 throughout the state. Rural communities comprise 7/48 (15%), and there are no wastewater treatment plants monitoring in frontier communities.

Figure 1.

Map of wastewater treatment plants monitored for SARS-CoV-2 in rural, urban, and frontier communities [46] in California.

Regional equity of California's wastewater monitoring

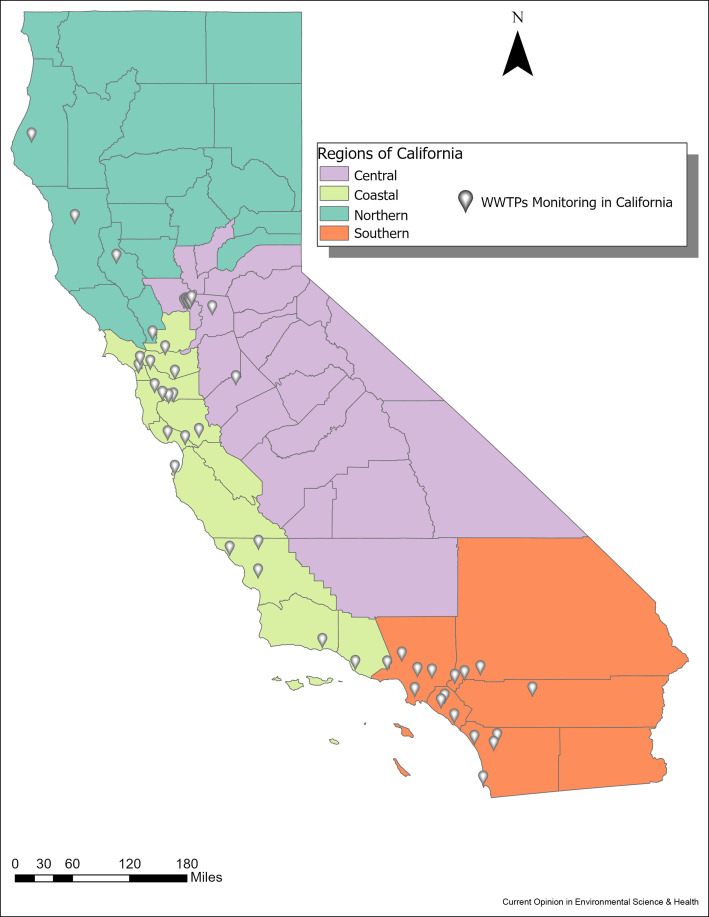

In addition to rural and urban representation, regional equity must also be considered for states and country monitoring efforts. Figure 2 shows the WWTPs monitored for SARS-CoV-2 in California over the major regions of California (Central, Coastal, Southern, Northern) [44,48]. There are 10 WWTPs monitored in the Central region, 18 in the Coastal region, 16 in the Southern region, and four in the Northern region (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Map of wastewater treatment plants monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 in California compared to the major regions of California [44,48].

The total treatment plants per region in California include: the North (79 treatment plants), South (75 treatment plants), Central (122 treatment plants), and Coastal (102 treatment plants) [44]. Central (10/122, 8.2%) and Northern California (4/79, 5.1%) lack access to COVID-19 wastewater monitoring efforts [44] compared to Coastal (18/102, 18%) and Southern (16/75, 21%) California (see Figure 2).

Map of WBE efforts over environmental justice layers in California

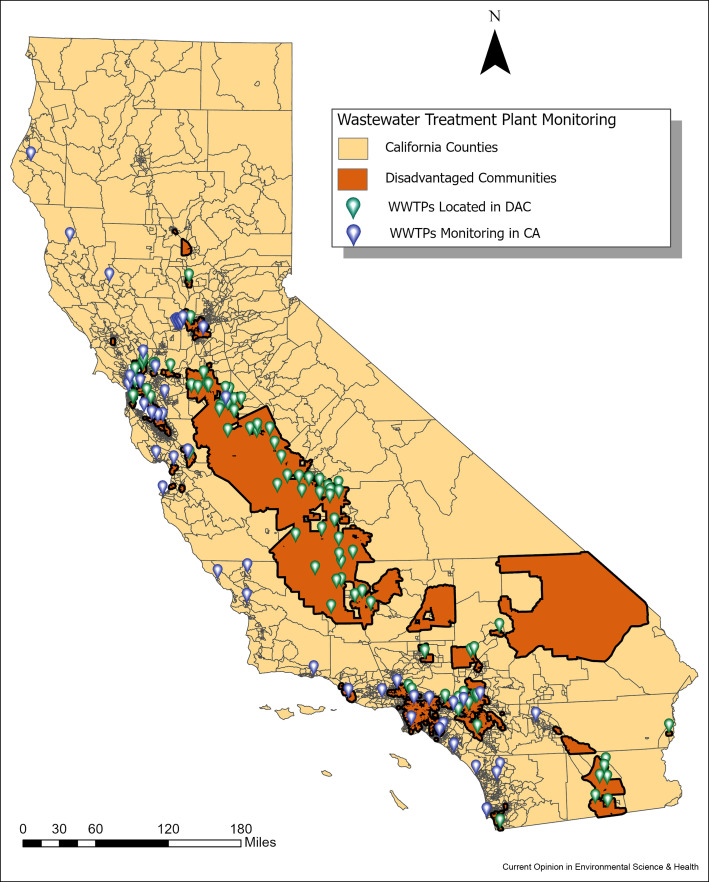

The California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) classifies Disadvantaged Communities (DAC) [45] as communities that may include, but are not limited to: “areas disproportionately affected by environmental pollution and other hazards that can lead to negative public health effects, exposure, or environmental degradation, and areas with concentrations of people that are of low-income, high unemployment, low levels of home ownership, high rent burden, sensitive populations, or low levels of educational attainment”. A higher percentile value for a county signifies greater environmental, economic, and/or educational disparities. CalEnviroScreen [45] defines a DAC as the top 25% scoring areas with high levels of pollution and smaller populations. Figure 3 displays WWTPs in DACs [45] in California compared to the WWTPs monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 throughout the state.

Figure 3.

Map of wastewater treatment plants in Disadvantaged Communities (DACs) [45] in California compared to the wastewater treatment plants monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 throughout the state.

There are 2022 DAC communities out of 8035 total communities throughout the state of California (25%) [45]. Out of the 48 WWTPs monitoring throughout California, 10 of them are located within DAC communities (21%) [45]. There are 90 total WWTPs located in DAC communities, and 10 of these are monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 (11%) [45]. This indicates a lack of wastewater monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 within DACs located throughout the State of California. Comparatively, 38 treatment plants were monitoring in non-DACs of 294 non-DAC wastewater treatment plants (12.9%). Though the percent monitoring in DACs and non-DACs is relatively similar (11.1%–12.9% respectively), DACs have higher COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths and have less access to public health resources as well as other environmental health burdens and need greater access to wastewater monitoring.

COVID-19 case proportion to population and wastewater monitoring in California

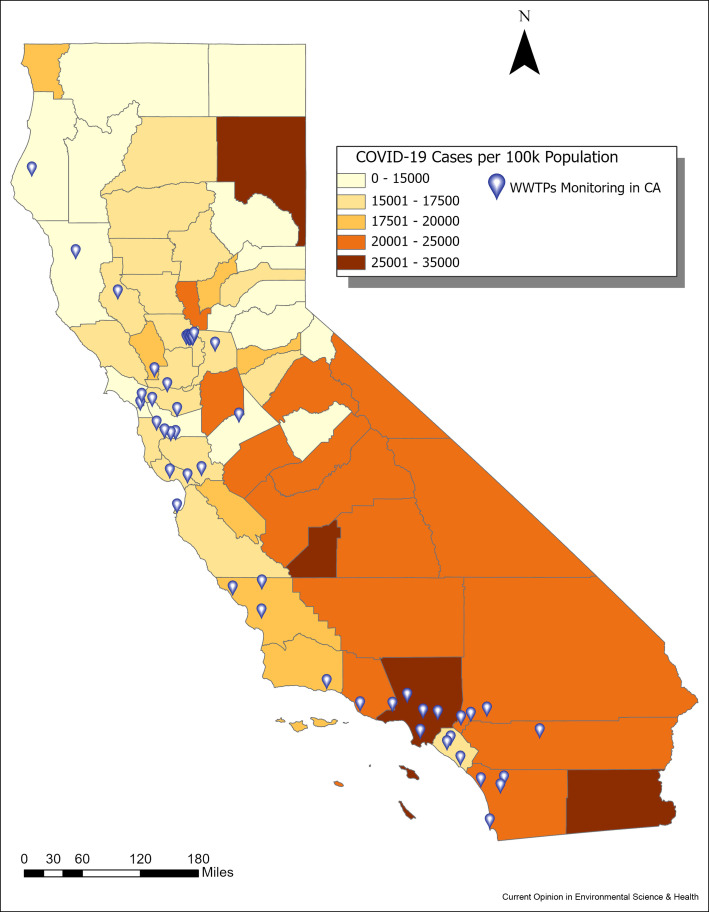

Another component of equity to consider is whether WBE monitoring of COVID-19 is occurring in the areas of highest COVID-19 prevalence and need. Figure 4 overlays WWTPs monitored for SARS-CoV-2 in California and the cumulative COVID-19 case counts, from March 3, 2020 to February 8, 2022, [47,49] per 100,000 population by county [48,50]. The highest ranking counties with COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population are Lassen (north), Kings (central), Los Angeles (south), and Imperial (south) counties. Out of these counties, Los Angeles has the highest number of wastewater treatment plants monitoring in the area. Central and Southern California counties experience moderate-high levels of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population with little access to wastewater monitoring.

Figure 4.

Map of wastewater treatment plants monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 in California compared to the cumulative COVID-19 case counts [47,49] per 100,000 population distributed by county [48,50].

Conclusions and recommendations

The world can utilize WBE as a public health tool to inform communities of potential outbreaks and use the data for localized solutions. WBE can additionally serve as a lower cost tool for COVID-19 testing and help focus resources to support individual testing efforts [13]. Mapping testing disparities like our review of COVID-19 wastewater monitoring efforts in California demonstrates the need for an environmental justice approach for WBE efforts overall. The application of WBE provides opportunities for equitable public health initiatives through systematic data collection. We encourage the expansion of wastewater testing to areas of need in California and globally particularly in Low and Middle Income Countries. Providing greater access to COVID-19 WBE will require improved [51] and innovative sampling methods such as sensors [52] especially for areas without centralized wastewater systems.

Credit author statement

Clara Medina: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft Krystin Kadonsky: Data Curation, Writing -Review & Editing, Visualization Fernando Roman: Data Curation, Writing -Review & Editing, Visualization Arianna Tariqi: Data Curation, Writing -Review & Editing, Visualization Ryan Sinclair: Writing -Review & Editing Patrick D'Aoust: Writing -Review & Editing Robert Delatolla: Writing -Review & Editing Heather Bischel: Writing -Review & Editing Colleen Naughton: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing -Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation Grant #2037834, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Center for Information Technology in the Interest of Society (CITRIS), Healthy Yolo Together (HYT) Initiative based at UC Davis, and the University of California's Leadership Excellence through Advanced DegreeS (UC LEADS) funded by the University of California's Office of the President (UCOP).

This review comes from a themed issue on Occupational Safety and Health 2022: COVID-19 in environment: Treatment, Infectivity, Monitoring, Estimation

Edited by Manish Kumar, Ryo Honda, Prosun Bhattacharya, Dan Snow and Payal Mazumder

References

- 1.Ranscombe P. Rural areas at risk during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30301-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Aoust P., Towhid S., Mercier E., Hegazy N., Tian X., Bhatnagar K., Zhang Z., Naughton C., MacKenzie A., Graber T., et al. COVID-19 wastewater surveillance in rural communities: comparison of lagoon and pumping station samples. Sci Total Environ. 2021;801:2–3. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R., Arif A., Adeyemi O., Ghosh S., Han D. Progression of COVID-19 from urban to rural areas in the United States: a spatiotemporal analysis of prevalence rates. J Rural Health. 2020;36:1–11. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study reported the prevalence of COVID-19 cases in comparison to the county-level determinants in urban and rural areas over the span of three weeks. Findings concluded higher prevalence of COVID-19 presence in counties with higher black populations, smoking rates, and obesity rates and is of special interest due to its connection with testing disparities in disadvantaged communities.

- Mueller J., McConnell K., Burow P., Pofahl K., Merdjanoff A., Farrell J. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural America. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am. 2021;118:1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019378118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study performs a statistical analysis to provide more insight on the impacts of COVID-19 on individuals living in rural communities throughout America.

- COVID-NET . CDC; July 16, 2021. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html URL: [Google Scholar]; This report from the CDC portrays vital information on differing racial and ethnic groups in the United States, and their risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death. Minority groups have an increased risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death.

- 6.Annual estimates of the resident population for the United States, regions, states, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2019 (NST-EST2019-02). U.S. Census Bur; URL: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-total.html.

- 7.COVID-NET: Hospitalization rates. CDC; URL: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covid-net/purpose-methods.html.

- 8.National Center for Health Services: Provisional COVID-19 deaths: distribution of deaths by race and Hispanic origin. CDC; URL: https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-COVID-19-Deaths-Distribution-of-Deaths/pj7m-y5uh.

- 9.Waterborne disease & outbreak surveillance reporting. Wastewater Surveillance. CDC; June 23, 2021. www.cdc.gov/healthywater/surveillance/wastewater-surveillance/wastewater-surveillance.html URL: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitney O., Kennedy L., Fan V., Hinkle A., Kantor R., Greenwald H., Crits-Christoph A., Al-Shayeb B., Chaplin M., Maurer A., et al. Sewage, salt, silica, and SARS-CoV-2 (4S): an economical kit-free method for direct capture of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from wastewater. ACS. 2021;55:4880–4888. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c08129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris-Lovett S., Nelson K., Beamer P., Bischel H., Bivins A., Bruder A., Butler C., Cemenisch T., De Long S., Karthikeyan S., et al. Wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 on college campuses: initial efforts, lessons learned and research needs. NIH. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.01.21250952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong J., Tan J., Lim Y., Arivalan S., Hapuarachchi H., Mailepessov D., Griffiths J., Jayarajah P., Setoh Y., Tien W., et al. Non-intrusive wastewater surveillance for monitoring of a residential building for COVID-19 cases. Sci Total Environ. 2021:786. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naughton C.C., Roman F., Jr., Alvarado A., Tariqi A., Deeming M., Bibby K., Bivins A., Rose J., Medema G., Ahmed W., et al. Show us the data: global COVID-19 wastewater monitoring efforts, equity, and gaps. medRxiv. 2021;1:1–15. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.14.21253564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escobar G., Adams A., Liu V., Soltesz L., Chen Y., Parodi S., Ray G., Myers L., Ramaprasad, Dlott R., et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 testing and outcomes: retrospective cohort study in an integrated health system. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174 doi: 10.7326/M20-6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Learn about environmental justice. US EPA; URL: https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/learn-about-environmental-justice.

- 16.Town of discovery bay community services district, wastewater treatment plant, Contra Costa county. Cen Val Water Board; URL: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/rwqcb5//board_decisions/tentative_orders/1406/23_discoverybay/1_discoverybay_buff.pdf.

- 17.Department of Toxic Substances Control: California environmental quality act initial study. CA EPA; URL: https://files.ceqanet.opr.ca.gov/256468-2/attachment/fzt8f1DrAAMC0DrV2PTYEASZy_QK_jeUB1f3y2Ezlp17qm8Kpy1ncm5Tzci7DQPd-YVG1-Z7MYEE6Hj40.

- 18.State Water Resources Control Board: Facility at-a-glance report - Calaveras. CA EPA; URL: https://ciwqs.waterboards.ca.gov/ciwqs/readOnly/CiwqsReportServlet?reportName=facilityAtAGlance&placeID=235798.

- 19.City of Gridley, Gridley wastewater treatment plant, Butte County. CSPA; URL: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/rwqcb5//board_decisions/tentative_orders/0612/gridley/gridley-wwtp-buff.pdf.

- 20.State Water Resources Control Board: Facility at-a-glance report - Amador. CA EPA; URL: https://ciwqs.waterboards.ca.gov/ciwqs/readOnly/CiwqsReportServlet?inCommand=drilldown&reportName=facilityAtAGlance&placeID=226847&reportID=9515435.

- 21.Wastewater system: collection, treatment & disposal. Bear Val Water Dis; URL: https://bvwd.ca.gov/treatment.aspx.

- 22.Allen, B: City and county of San Francisco, Sunol Valley golf course, Sunol, Alameda County - rescission of water reclamation requirements order no. 88-037. Reg Water Qua Con Board; URL: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/sanfranciscobay/board_info/agendas/2017/May/5e_ssr.pdf.

- 23.Kolodzie, K: Dublin-San Ramon WWTF 2012 clean watershed needs survey. US EPA; URL: https://cwns.epa.gov/cwns2012/factsheets/06002006001.pdf.

- 24.COVID 19 resource links. BACWA; URL: https://bacwa.org/general/covid-19-resources-updated-april-2020/.

- 25.Melitas, N: LA county sanitation district testing wastewater for coronavirus. California Water News Daily; URL: http://californiawaternewsdaily.com/industry/la-county-sanitation-district-testing-wastewater-for-coronavirus/.

- 26.Sewer Coronavirus Alert Network (SCAN): Wastewater treatment plant sites. Stanford University; URL: https://suwater.stanford.edu/wastewater-overview.

- 27.Ibarra, N, Pickett, M: They’re testing your what? Wastewater plays growing role in search for COVID-19 countywide. Lookout Santa Cruz; URL: https://lookout.co/santacruz/coronavirus/story/2021-01-17/santa-cruz-county-search-covid-19-wastewater.

- 28.LA wastewater tells a story of monitoring COVID-19: how LA county tracks COVID-19 surges in wastewater. Zymo Research; URL: https://www.zymoresearch.com/blogs/blog/la-wastewater-tells-a-story-of-monitoring-covid-19.

- 29.California wastewater utilities participating in COVID sewer surveillance. CWEA; URL: https://www.cwea.org/news/california-wastewater-utilities-participating-in-covid-19-sewer-surveillance/.

- 30.Papanek, M: Wastewater testing reveals COVID-19 spike in Rio Dell, city officials say. KRCR 7; URL: https://krcrtv.com/north-coast-news/eureka-local-news/wastewater-testing-reveals-covid-19-spike-in-rio-dell-city-officials-say.

- 31.McCrohan, D: Researchers hunt for coronavirus in Tiburon Peninsula sewage. The Ark; URL: https://www.thearknewspaper.com/single-post/2020/11/18/researchers-hunt-for-coronavirus-in-tiburon-peninsula-sewage.

- 32.Healthy Yolo Together: Neighborhood Wastewater Data. UC Davis; URL: https://healthydavistogether.org/wastewater-testing/#/central-davis/recent.

- 33.Degan, R: Central San teams up with UC Berkeley for COVID-19 wastewater research project. Danville San Ramon; URL: https://www.nacwa.org/news-publications/news-detail/2021/01/22/central-san-teams-up-with-uc-berkeley-for-covid-19-wastewater-research-project.

- 34.La Plante, M: Researchers turn to human waste to study COVID-19 in Santa Clara County. Palo Alto Online; URL: https://paloaltoonline.com/news/2020/12/29/researchers-turn-to-human-waste-to-study-covid-19-in-santa-clara-county.

- 35.CDM Smith partners with US Department of Veterans Affairs for COVID wastewater testing at 8 community living centers. CDM Smith; URL: https://cdmsmith.com/en/News/Veterans-Affairs-COVID-Wastewater-Testing.

- 36.Lin II, RG, Money, L: Skyrocketing coronavirus levels in California sewage point to rapid spread of virus. Los Angeles Times; URL: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-12-17/skyrocketing-levels-of-covid-in-california-sewage-points-to-rapid-spread-of-virus-this-fall.

- 37.San Diego starts monitoring wastewater for virus. NBC San Diego; URL: https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/local/san-diego-starts-monitoring-wastewater-for-virus/2472229/.

- 38.Olalde, M: COVID-19 virus in Palm Springs' wastewater surged more than 700% in November, report says. Palm Springs Desert Sun; URL: https://www.desertsun.com/story/news/health/2020/12/10/covid-19-virus-palm-springs-wastewater-skyrocketed-november/3881377001/.

- 39.Lin, S: ‘Increased’ levels of COVID-19 found in Davis neighborhood wastewater. KCRA 3; URL: https://www.kcra.com/article/increased-levels-covid-davis-neighborhood-wastewater/36069041.

- 40.Medina, C: Equity of wastewater monitoring in CA of SARS-CoV-2. ArcGIS Online; URL: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/aaa7e1780d70414a9c35923d98db13fb.

- 41.Harrington R., Califf R., Balamurugan A., Brown N., Benjamin R., Braund W., Hipp J., Konig M., Sanchez E., Maddox K. Call to action: rural health: a presidential advisory from the American heart association and American stroke association. Circulation. 2020;141:615–644. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas K., Hillary Luke, Malham Shelagh, McDonald James, Jones David. Wastewater and public health: the potential of wastewater surveillance for monitoring COVID-19. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2020;17:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Of outstanding interest, this was one of the early papers in the COVID-19 pandemic to review the potential public health importance of wastewater surveillance. This paper further showcases the methodology involved for wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2, the challenges, need for further research, and how implementation of a surveillance system is well-suited for urban communities.

- Soria A., Galimberti S., Lapadula G., Visco F., Ardini A., Valsecchi M.G., Bonfanti P. The high volume of patients admitted during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has an independent harmful implant on in-hospital mortality from COVID-19. PLoS One. 2021 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study is of special interest because it reveals the independent impact that the high volume of COVID-19 patient influx has on hospitals and patient mortality rates. It presents a solid statistical analysis on the distribution of inpatients over time taking into account variables that stress the hospitals' resource availabilities.

- 44.California regions. California Census; 2020. https://census.ca.gov/regions/ URL: [Google Scholar]

- 45.California Office of environmental health hazard assessment (OEHHA); URL: https://oehha.ca.gov/calenviroscreen/report/calenviroscreen-30 (accessed August 30, 2021).

- 46.Medical Service Study Areas. California state geoportal; URL: https://gis.data.ca.gov/datasets/CHHSAgency::medical-service-study-areas/about (accessed August 30, 2021).

- 47.California coronavirus map: what do the trends mean for you?. Mayo Clinic; URL: https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus-covid-19/map/california (accessed August 30, 2021).

- 48.California County Boundaries. California Department of Technology; URL: %%https://gis.data.ca.gov/datasets/CALFIRE-Forestry::california-county-boundaries/explore?location=34.263626%2C-118.940734%2C5.00.

- 49.Tracking COVID-19 in California. California for All. California Department of Public Health; URL https://covid19.ca.gov/state-dashboard/#location-california.

- 50.Population of Counties in California . 2022. World population review.https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-counties/states/ca URL. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barcelo D. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology to monitor COVID-19 outbreak: present and future diagnostic methods to be in your radar. CSCEE. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hui Q., Pan Y., Yang Z. Paper-based devices for rapid diagnostics and testing sewage for early warning of COVID-19 outbreak. CSCEE. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]