Abstract

Among pathologies of the shoulder, rotator cuff tear is the most common. Diagnosis of cuff tear around mid twenties is unusual, but the prevalence increases significantly after the age of forty. The prevalence after the age of 60 is around 20–30%. A well recognised feature of cuff tear is being asymptomatic but, tear progression in asymptomatic is a known consequence. The spectrum of cuff tear ranges from partial, full thickness cuff tear with or without retraction. The mainstay of treatment for partial thickness cuff tear is systematic rehabilitation and for the full thickness cuff tear an initial rehabilitation is an accepted management. Failed rehabilitation for 3 months, acute traumatic tear, younger age, intractable pain, good quality muscle would be the indications for repair of a full thickness cuff tear. Though there are defined indications for surgical intervention in the full thickness rotator cuff tear, differentiating an asymptomatic tear that would not progress or identifying a tear that would become better with rehabilitation is an undeniable challenge for even the most experienced surgeon.

Rehabilitation in cuff tear consists of strengthening the core stabilizers along with rotator cuff and deltoid muscles. In a symptomatic cuff tear that merits surgical intervention the objective is to do an anatomical foot print repair. In scenarios where the cuff is retracted, one has to settle for a medialised repair. As, a repair done in tension is more likely to fail than a tensionless medialised repair. The success rate of all these non anatomical procedures varies from series to series but it approximates around 60–80%.

Augmenting cuff repair to enhance biological healing is a recent advance in rotator cuff repair surgery. The augmentation factors can be growth factors like PRP, scaffolds both auto and allografts. The outcome of these procedures from literature has been variable. As there are no major harmful effects, it can be viewed as another future step in bringing better outcomes to patients having rotator cuff tear surgery.

Despite being the commonest shoulder pathology, the rotator cuff tear still remains as a condition with varied presenting features and a wide variety of management options. The goal of the treatment is to achieve pain free shoulders with good function. Correcting altered scapular kinematics by systematic rehabilitation of the shoulder would be the first choice in all partial thickness cuff tear and also as an initial management of full thickness cuff tears. Failure of rehabilitation would be the step forward for a surgical intervention. While embarking on a surgical procedure, correct patient selection, sound surgical technique, appropriate counselling about expected outcome are the most essential in patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Rotator Cuff, Shoulder arthroscopy, Cuff repair, Cuff tear, Shoulder pain

1. Introduction

Rotator cuff tear is the most common shoulder problem and its prevalence ranges from 5 to 30%.1, 2, 3 Yamamoto et al.1 in their screening of 1366 shoulders showed that 20.7% had cuff tears. Minagawa et al.2 in their screening of 664 subjects found 22.1%(147) to have cuff tear, of which 65.3% (51 out of 147) were asymptomatic. They also showed that the prevalence of rotator cuff increases with age. Cuff tear in less than 20 years were 0% and reached almost 37% in those older than 80 years. Moreover, the prevalence of asymptomatic cuff tear was significantly greater than those with symptomatic tear (p less than 0.0001). The earliest known description of rotator cuff dates back to 1788, when Monro described a tear in supraspinatus. However, the first surgical attempt to repair was done in the year 1906 by Perthes.4 Treatment of cuff tear has come a long way, from open repair to arthroscopic surgeries, from just repair to repair augmentation.

1.1. Natural history of cuff tear

To derive a management plan, it is of prime importance for the surgeon to appreciate the natural consequence of an untreated cuff tear. Majority of the cuff tears are degenerative in nature and the prevalence increases with age,3 few even consider it to be a part of the aging process.5 Codding et al.5 in their review of degenerative rotator cuff tear, explained about the natural history of degenerative cuff tear.

-

1)

The degenerative tear commonly begins at the junction of the posterior supraspinatus and anterior edge of infraspinatus (13–17 mm posterior to the biceps tendon within the rotator crescent6).

-

2)

Fatty degeneration increases as the tear size propagates.

-

3)

Once the propagation reaches the threshold size (≥175 mm27) proximal humeral migration occurs, resulting in cuff arthropathy.

As degenerative cuff tear progress there is a risk of tear enlargement. Keener et al.7 in their analysis of 224 subjects with a follow up of 5.1 years showed that 49% of the individuals had tear progression and the median time to reach tear progression was 2.8 years. Apart from tear progression, rotator cuff tear causes fatty degeneration of the cuff muscles. Davies et al.8 evaluated full thickness rotator cuff tears in 156 shoulders with ultrasonography annually for a median duration of 6 years.They concluded that fatty degeneration is more common in larger tears. Moreover, in older patients the progression of fatty degeneration is more frequent with tear enlargement. Most degenerative tears are asymptomatic but some develop pain, the factors contributing for development of pain are still under research. Dunn et al.9 evaluated 393 patients with atraumatic full thickness tears. By multivariable modeling they concluded that pain in degenerative tears is linked with comorbidities (p = 0.002), lower education (p = 0.004) and race (p = 0.041). While other factors like cuff tear severity, including the number of tendons involved (p = 0.5), amount of retraction (p = 0.9), presence of humeral head migration (p = 0.3), and amount of fatty degeneration of the supraspinatus (p = 0.4), were not linked with development of pain. Chalmers et al.10 prospective evaluation of progression to arthritis in asymptomatic rotator cuff tear included 138 patients (28% had partial cuff tear, 49% had full thickness tear, 24% were control). At 5 years follow up the Samilson-Prieto grades, Hamada grade showed significant progression from baseline. Even though a significant number of people develop pain, arthritis and fatty degeneration with rotator cuff tear an attempt at conservative management is a valid option, as many respond to it.

-

A)

Conservative management of rotator cuff tear:

Pain and weakness is the prime symptom for which a patient seeks attention to a medical practitioner. The causes of pain in the cuff tear are synovitis, subacromial bursitis, impingement pain and arthritis.11 Alteration of scapular kinematics is undoubtedly common in all patients with rotator cuff tear.12 A short duration of analgesics and anti inflammatory drugs

along with therapeutic modalities will help to relieve the inflammation around the shoulder joint. Improving scapular kinematics is the key to get a desired improvement in pain as well as function.13

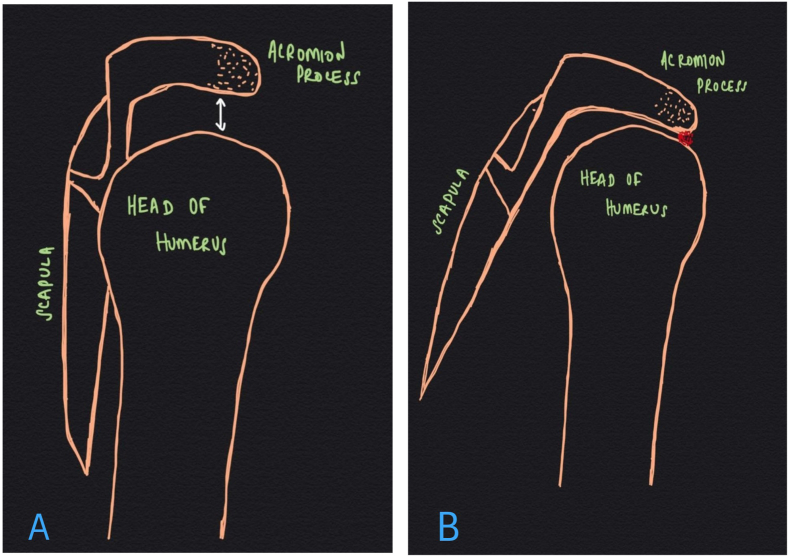

The pathophysiology of alteration in scapular kinematics has to be well understood in order to deliver the right treatment for the patient. A stooped posture with anteriorly tilted scapula is a predisposing risk factor for the subacromial pain and rotator cuff tear. A scapula that is anteriorly tilted due to muscle imbalance will reduce the subacromial space (Fig. 1) This eventually results in subacromial impingement.14 Correcting core stabilizers of the scapula corrects this abnormal scapular kinematics and should be the main objective of conservative therapy. The rehabilitation therapist should aim to improve strength of Rhomboids, Levator scapulae, Serratus anterior, Latissimus Dorsi, Teres major and trapezius. A dedicated therapy will correct the anterior tilting of the scapula and hence the subacromial space will become wider eventually relieving the subacromial pain. Similarly strengthening the deltoid and biceps also helps to compensate for the rotator cuff weakness.

-

B)

Surgical management of Rotator cuff tear

Fig. 1.

A) Shows the normal scapular position and the normal subacromial space. B) Shows the decreased subacromial space due to the anterior tilting of scapula, which is present in stooped posture.

The indications for surgery in rotator cuff tear are persistence of symptoms like pain after rehabilitation, traumatic full thickness tear, good muscle quality as in younger individuals and pseudoparalysis.15

While adopting for surgical intervention, all sources of pain should be considered. The sources of pain are cuff tear, subacromial bursa, biceps tendon attachment, a tight capsule, degenerative symptomatic acromioclavicular joint and a tight subacromial space with hooked acromion.16 So the surgery should address all these potential pain generating pathologies.

1.2. Surgical techniques

The Objective of rotator cuff repair is to achieve anatomical reduction of the cuff tear to the foot print. Age of the patient,duration of tear, extent of tear and quality of tendon dictates the healing potential of the repaired cuff.17

The Principles in achieving healing of repaired cuff is to preserve biology as much as we can. A tension free repair, freshened tendon ends, secure fixation over the cancellous surface in the foot print area are essentials to get proper healing of the rotator cuff.

Mobilizing Rotator cuff is the prime step in cuff repair surgery18 and it should be emphasized to beginners that certain time spent to achieve good mobility of the cuff is certainly worthwhile to ensure good healing of the cuff.19 A small to moderate cuff tear of a shorter duration will usually be reduced by gentle pull with a cuff grasper. In cases where the mobility of the cuff is restricted, the following steps are advised.

-

1]

Sub acromial bursa should be excised with the help of arthroscopic shaver from anterior end to posterior end and also from medial to lateral end

-

2]

If the subacromial space is tight, performing acromioplasty will improve the space and also releasing the coracohumeral ligament will help to achieve excursion of the torn cuff.

-

3]

Passing an arthroscopic liberator in between the supraspinatus and glenoid will release the supra glenoid adhesions, this step should be done from 9 O'clock to 3 O'clock around the supra glenoid area.

-

4]

With the above measures most of the cuff can be mobilized and will be able to reach the foot print area. Occasionally even after these steps the cuff would be immobile and would need an interval release19

Before passing the suture materials, it should be ensured that the torn end of the tendon are fresened. A gentle excision of 1or 2 mm of the torn end will ensure fresh biological activity in the torn end.

In the greater tuberosity the foot print should be delineated from medial to lateral and from anterior to posterior. A ring curette is a useful tool to denude the cortical bone minimally. It is important to see the exposure of cancellous bone over the footprint area. In occasional cases where there is sclerosis one has to use arthroscopic burr to freshen the foot print.

Secure fixation is the key for successful healing of the rotator cuff.It is nevertheless important to emphasis the dimension of foot print (17 × 32 mm20).This essentially means whenever possible it is important to span 17 × 32 mm of tissue in the greater tuberosity footprint area.The ideal way to achieve this will be by placing a medial anchor near the articular surface margin and using a lateral anchor over the metaphysis of the greater tuberosity (Fig. 2). This means a double row repair will inevitably give an anatomical secure footprint fixation.21 Usually, two double loaded anchors abuting the articular margin and two lateral row knotless anchors will ensure secure fixation. In scenarios where there is too much tension on the cuff an anatomical reduction is not possible. In such cases one can use a medicalised single row repair alone23 (Figure 3). The number of sutures that should go through the cuff should be dictated by the extent of tear in the Anteroposterior direction.The gap between sutures should not be more than 0.5 cm in order to have decent coverage of the cuff tissue.22

Fig. 2.

A) Denotes the coronal view of double row repair of rotator cuff. Note the placement of medial row anchors just lateral to the articular margin and the lateral row anchors placed far lateral in the footprint. B) Denotes the same in axial view. C & D) are the cuff after tying the knot of the suture anchor in coronal and axial view. Note that double row repair covers the whole of the footprint area with the cuff, after repair.

Fig. 3.

A) Denotes the coronal and (B) axial view of a medial row repair. If the cuff is immobile a single row medial row can be considered. C & D) Coronal and Axial view after medial row repair. Note how the footprint is left exposed even after cuff repair.

Mastering cuff repair surgery fully relies on getting enough visibility of the pathology.The Visibility depends on the appropriate portal placement. Conventional portals are posterior portal, lateral portal and anterior portal. However, in rotator cuff surgery apart from conventional portals accessory portals are required. The position of accessory portals are dictated by the location of the pathology. The author's preference (KNS) is to enter the subacromial space from the posterior portal to identify the gross pathology and then use a 18 G spinal needle from the lateral side to mark the pathological site. Next, the wessinger rod is introduced exactly near the pathological area and the arthroscope is shifted there. The accessory portals are made to access the torn cuff using the same spinal needle. The anchors are introduced through a separate stab incision directly targeted to the desired point of insertion in the footprint. Next, suture materials are retrieved through a cannula in the lateral portal and several stitches are made through the cuff and fixed with a sliding or non-sliding knot. Following these steps systematically will ensure the progress of surgery smoothly and swiftly.

1.3. Transosseous repair of rotator cuff

Transosseous technique of repairing rotator cuff is an alternative option for similar indications. The advantage of transosseous repair is evading the use of anchors and avoiding the downside of anchors such as cost and anchor failures. A transosseous repair is done with the help of a transosseous jig and creating a bone tunnel. Suture material is passed through the cuff and bone tunnels and tied firmly to the “footprint. A biomechanical study in cadaver comparing the anchorless technique and transosseous equivalent technique (TOE) showed that TOE has a significantly higher load to failure and had a significantly less mean first cycle excursion.24 Beauchamp et al.25 analysis of functional outcome of arthroscopic transosseous repair using 2 mm tape in 137 patients has shown a significant improvement in Quick Dash and ASES score postoperatively, and there was no difference in the outcome of patients older than 65 and younger than 65. However, a poor bone quality is a deterrent for a transosseous technique as the suture materials can cut through the bone.

1.4. Non anatomical procedures for irreparable rotator cuff tear

A cuff tear with grade 4 fatty atrophy and retraction to glenoid is an irreparable tear. As these tears cannot be mobilized to greater tuberosity, the alternative is to do non anatomical procedures. Reverse shoulder replacement is the choice when there is proximal humeral migration with secondary arthropathy.26 Whereas, in scenarios of irreparable rotator cuff tear with no arthritis a soft tissue procedure such as Latissimus dorsi transfer or a Superior capsular reconstruction should be considered. Latissimus dorsi transfer has been known for decades and its outcome ranges from 60 to 80% in the experienced.27 The Superior capsular reconstruction uses fascia lata autograft to replace the damaged cuff. In Superior capsular reconstruction fascia lata is fixed to the glenoid and the footprint of greater tuberosity with the help of anchors. It acts as a restraint for proximal migration and also would function as a lever when abduction is carried out. The results from the proponents range to 80%.28 It is a technique with a steep learning curve with promising results when properly performed.

1.5. Outcome of rotator cuff repair surgery

An anatomical foot print repair along with good approximation with no tension at the fracture site has a good success in relieving pain and gaining function. A larger tear, poor muscle quality, non anatomical repairs, elderly patients, and those with poor bone quality are predisposed to retear and a suboptimal outcome.29The retear rate for rotator cuff post surgeries remains as high as 20–40% for small tears and even 94% for large tears.30,31 After surgical repair of the rotator cuff, the 4-layer rotator cuff insertion site may not be restored. Post operatively, a disorganized fibrous scar tissue is formed between tendons and bone and this poorly mineralized fibrocartilage tissue predisposes to postoperative failure.32 Hence there is an argument to use augmentation factors to help improve the healing of cuff tissues to bone. The augmentations that are used are Growth factor and scaffolds.

-

C)

Augmentation of Rotator Cuff Repair

1.6. Growth factors

There is a fair amount of controversy on the efficacy of growth factors in rotator cuff healing.

PRP are not only rich in platelets but also in fibrin, clotting factors, growth factors (PDGF AA (Platelet Derived Growth Factor), PDGF-BB, and PDGF-AB, Transforming Growth Factor - TGF-Beta 1 and 2, Endothelial growth factor) and leukocytes.33 There are two major variants in the growth factors - Platelet rich plasma and Platelet rich fibrin. The platelets in these two are either pure platelet (PPRP/PPRF) or Leukocyte rich Platelets(LPRP/LPRF).Hurley et al.31 in their meta-analysis of RCTs comparing platelet rich plasma and platelet rich fibrin (both leukocyte rich and poor). 12 studies included were based on PRP (9 - LPRP, 3 - PPRP) and 6 were based on PRF(PPRF - 4 studies, LPRF - 2 studies). The tendon healing rate with the use of PRP compared with control was statistically significant in small-medium tears (RR - 0.59) as well as in medium large tears (RR - 0.38). While the tendon healing rate for PRF was not statistically significant (RR - 0.95).

1.7. Scaffolds

The two rationale for the use of scaffolds are 1) mechanical augmentation - offloading the repair from surgery and some days postoperatively. 2) Biological augmentation - improves the healing rate and quality of healing.34 Scaffolds are either biological or synthetic. Biological scaffolds are derived usually from human dermal tissues or from porcine dermis or small intestine submucosa. These porcelain tissues even though claimed to be acellular usually have remnant DNA and initiates inflammatory reaction.35,36 Though synthetic scaffolds can elicit inflammatory reactions, they are usually of chronic inflammatory type and the duration and intensity depends upon the composition.34

Allograft like GraftJacket has shown promising results. A randomised control trial by Barber et al.37 in 42 patients (Group 1 - 22 augmented with graft and Group 2–20 without augmentation). After a mean followup of 24 months, the functional outcome calculated by UCLA, Constant scores were statistically increased in the group 1 patients. Moreover, Gadolinium enhanced MRI showed a 85% intact cuff in the group 1 and just 40% in the group 2 patients.

Synthetic grafts on the other hand are not as favourable as that of allograft. Ranebo et al.38 in their long term (mean - 18 years) assessment of 12 patients with synthetic interposition graft (Dacron), 9 developed cuff tear arthropathy. Moreover 7 out of 10 patients who had ultrasound, the cuff was found to be not intact. They concluded that irreparable cuffs causing a bridging gap, repaired with synthetic interposition cannot prevent arthropathy and preserve integrity.

The scaffolds do have a role in certain selected cases of massive irreparable cuff tear. The symptomatic improvement has been variable and the outcome on a long term is yet to be proved.

2. Conclusion

Despite being the commonest shoulder pathology, the rotator cuff tear still remains as a condition with varied presenting features and a wide variety of management options. The goal of the treatment is to achieve pain free shoulders with good function. Correcting altered scapular kinematics by systematic rehabilitation of the shoulder would be the first choice in all partial thickness cuff tear and also as an initial management of full thickness cuff tears. Failure of rehabilitation would be the step forward for a surgical intervention. A surgical intervention should aim to get anatomical repair. The outcome of repair is good in anatomical foot print repair. In a retracted tear the alternate options such as tendon transfer, superior capsular reconstruction should be considered. Most important of all is to have appropriate patient counselling of realistic outcomes to get optimal patient satisfaction.

Source of funding

Nil.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

Nil.

Contributor Information

Akil Prabhakar, Email: akil.prabhakar@gmail.com.

Jeash Narayan Kanthalu Subramanian, Email: ksjeash@gmail.com.

P. Swathikaa, Email: swathikaaponnuraj@gmail.com.

S.I. Kumareswaran, Email: kumaresh3788@gmail.com.

K.N. Subramanian, Email: knsubra@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Yamamoto A., Takagishi K., Osawa T., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010 Jan;19(1):116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minagawa H., Yamamoto N., Abe H., et al. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: from mass-screening in one village. J Orthop. 2013 Feb 26;10(1):8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teunis T., Lubberts B., Reilly B.T., Ring D. A systematic review and pooled analysis of the prevalence of rotator cuff disease with increasing age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014 Dec;23(12):1913–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tokish J.M., Hawkins R.J. Current concepts in the evolution of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2021 May;1(2):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.xrrt.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codding J.L., Keener J.D. Natural history of degenerative rotator cuff tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018 Feb 6;11(1):77–85. doi: 10.1007/s12178-018-9461-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H.M., Dahiya N., Teefey S.A., et al. Location and initiation of degenerative rotator cuff tears: an analysis of three hundred and sixty shoulders. J Bone Jt Surg A. 2010 May;92(5):1088–1096. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keener J.D., Wei A.S., Kim H.M., Steger-May K., Yamaguchi K. Proximal humeral migration in shoulders with symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears. J Bone Jt Surg A. 2009 Jun;91(6):1405–1413. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hebert-Davies J., Teefey S.A., Steger-May K., et al. Progression of fatty muscle degeneration in atraumatic rotator cuff tears. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2017 May 17;99(10):832–839. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn W.R., Kuhn J.E., Sanders R., et al. Symptoms of pain do not correlate with rotator cuff tear severity: a cross-sectional study of 393 patients with a symptomatic atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tear. J Bone Jt Surg. 2014 May 21;96(10):793–800. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalmers P.N., Salazar D.H., Steger-May K., et al. Radiographic progression of arthritic changes in shoulders with degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016 Nov;25(11):1749–1755. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garving C., Jakob S., Bauer I., Nadjar R., Brunner U H. Impingement syndrome of the shoulder. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2017 Nov;114(45):765–776. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barcia A.M., Makovicka J.L., Spenciner D.B., et al. Scapular motion in the presence of rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021 Jul 1;30(7):1679–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kibler W.B., Ludewig P.M., McClure P.W., Michener L.A., Bak K., Sciascia A.D. Clinical implications of scapular dyskinesis in shoulder injury: the 2013 consensus statement from the ‘scapular summit. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Sep 1;47(14):877–885. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludewig P.M., Braman J.P. Shoulder impingement: biomechanical considerations in rehabilitation. Man Ther. 2011 Feb;16(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh L.S., Wolf B.R., Hall M.P., Levy B.A., Marx R.G. Indications for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007 Feb;455:52–63. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31802fc175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews J.R. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic painful shoulder: review of nonsurgical interventions. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2005 Mar;21(3):333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen A.R., Taylor A.J., Sanchez-Sotelo J. Factors influencing the reparability and healing rates of rotator cuff tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020 Jul 17;13(5):572–583. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09660-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arrigoni P., Fossati C., Zottarelli L., Ragone V., Randelli P. Functional repair in massive immobile rotator cuff tears leads to satisfactory quality of living: results at 3-year follow-up. Musculoskelet Surg. 2013 Jun;97(S1):73–77. doi: 10.1007/s12306-013-0252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo I.K.Y., Burkhart S.S. Arthroscopic repair of massive, contracted, immobile rotator cuff tears using single and double interval slides: technique and preliminary results. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2004 Jan;20(1):22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis A.S., Burbank K.M., Tierney J.J., Scheller A.D., Curran A.R. The insertional footprint of the rotator cuff: an anatomic study. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2006 Jun;22(6):603–609.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noticewala M.S., Ahmad C.S. Double-row rotator cuff repair: the new gold standard. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015 Mar;16(1):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jost P.W., Khair M.M., Chen D.X., Wright T.M., Kelly A.M., Rodeo S.A. Suture number determines strength of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2012 Jul 18;94(14) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y.-K., Jung K.-H., Won J.-S., Cho S.-H. Medialized repair for retracted rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017 Aug;26(8):1432–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilcoyne K.G., Guillaume S.G., Hannan C.V., Langdale E.R., Belkoff S.M., Srikumaran U. Anchored transosseous-equivalent versus anchorless transosseous rotator cuff repair: a biomechanical analysis in a cadaveric model. Am J Sports Med. 2017 Aug;45(10):2364–2371. doi: 10.1177/0363546517706136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beauchamp J.-É., Beauchamp M. Functional outcomes of arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair using a 2-mm tape suture in a 137-patient cohort. JSES Int. 2021 Nov;5(6):1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2021.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolan B.M., Ankerson E., Wiater J.M. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty improves function in cuff tear arthropathy. Clin Orthop. 2011 Sep;469(9):2476–2482. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1683-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donaldson J., Pandit A., Noorani A., Douglas T., Falworth M., Lambert S. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfers for rotator cuff deficiency. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2011;5(4):95–100. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.91002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimock R.A.C., Malik S., Consigliere P., Imam M.A., Narvani A.A. Superior capsule reconstruction: what do we know? Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2019 Jan;7(1):3–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longo U.G., Carnevale A., Piergentili I., et al. Retear rates after rotator cuff surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2021 Aug 31;22(1):749. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04634-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel S., Gualtieri A.P., Lu H.H., Levine W.N. Advances in biologic augmentation for rotator cuff repair. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Nov;1383(1):97–114. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurley E.T., Colasanti C.A., Anil U., et al. The effect of platelet-rich plasma leukocyte concentration on arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Jul;49(9):2528–2535. doi: 10.1177/0363546520975435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Del Buono A., Oliva F., Longo U.G., et al. Metalloproteases and rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012 Feb;21(2):200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dohan Ehrenfest D.M., Andia I., Zumstein M.A., Zhang C.-Q., Pinto N.R., Bielecki T. Classification of platelet concentrates (Platelet-Rich Plasma-PRP, Platelet-Rich Fibrin-PRF) for topical and infiltrative use in orthopedic and sports medicine: current consensus, clinical implications and perspectives. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014 May 8;4(1):3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricchetti E.T., Aurora A., Iannotti J.P., Derwin K.A. Scaffold devices for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012 Feb;21(2):251–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Encalada-Diaz I., Cole B.J., MacGillivray J.D., et al. Rotator cuff repair augmentation using a novel polycarbonate polyurethane patch: preliminary results at 12 months’ follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011 Jul;20(5):788–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karuppaiah K., Sinha J. Scaffolds in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: current concepts and literature review. EFORT Open Rev. 2019 Sep 10;4(9):557–566. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barber F.A., Burns J.P., Deutsch A., Labbé M.R., Litchfield R.B. A prospective, randomized evaluation of acellular human dermal matrix augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2012 Jan;28(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranebo M.C., Björnsson Hallgren H.C., Norlin R., Adolfsson L.E. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcome of rotator cuff repair with a synthetic interposition graft: a consecutive case series with 17 to 20 years of follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Sep;27(9):1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]