Abstract

Background:

A social media campaign for mothers aimed at reducing indoor tanning (IT) by of adolescent daughters reduced mothers’ permissiveness toward IT in an immediate posttest. Whether the effects persisted at six months after the campaign remains to be determined.

Methods:

Mothers (N=869) of daughters aged 14–17 in 34 states without bans on IT by minors were enrolled in a randomized trial. All mothers received an adolescent health campaign over 12 months with posts on preventing IT (intervention) or prescription drug misuse (control). Mothers completed a follow-up at 18-months post-randomization measuring IT permissiveness, attitudes, intentions, communication, and behavior, and support for state bans. Daughters (n=469; 54.0%) just completed baseline and follow-up surveys.

Results:

Structural equation modeling showed that intervention-group mothers were less permissive of IT by daughters (unstandardized coefficient=−0.17, 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.31, −0.03), had greater self-efficacy to refuse daughter’s IT requests (0.17, 95% CI, 0.06, 0.29) and lower IT intentions themselves (−0.18, 95% CI, −0.35, −0.01), and were more supportive of bans on IT by minors (0.23, 95% CI, 0.02, 0.43) than control-group mothers. Intervention-group daughters expressed less positive IT attitudes than controls (−.16, 95% CI, 0.31, −0.01).

Conclusions:

The social media campaign may have had a persisting effect of convincing mothers to withhold permission for daughters to indoor tan for six months after its conclusion. Reduced IT intentions and increased support for bans on IT by minors also persisted among mothers.

Impact:

Social media may increase support among mothers to place more restrictions on IT by minors.

Keywords: skin cancer prevention, social media, mothers, adolescents

Introduction

Indoor tanning (IT), while decreasing in North America and Europe over the past decade, is still practiced by 5% to 10% of teens, most commonly by females.1,2 IT is related with a higher risk of developing melanoma and keratinocyte cancers.3,4 While prevention interventions have been effective,5–10 they have not had broad reach.

Little research has investigated social media in this realm, despite its popularity and potential reach. Young and middle-aged adults are heavy users of social media,11 so social media might reach and convince parents to prevent adolescent daughters from engaging in IT, especially in the 19 U.S. states where public policy requires parental permission or accompaniment for minors to access IT facilities. The effectiveness of these policies depend in part on parents withholding permission. However, parental-permission policies and other regulations that fall short of bans do not consistently reduce IT by minors12 due to many parents not recognizing the dangers of IT,13,14 as well as weak enforcement by state regulators and poor compliance by tanning facility operators.

Mothers’ permissiveness and tanning behavior are strongly associated with daughters’ IT behavior13–16 so they are an especially important audience for intervention. In one study, mothers’ permissiveness was reduced by well-crafted communication.17 Interventions might also motivate mothers to communicate about the harms of IT with adolescent daughters. Parent-child communication can reduce adolescent risk behaviors18–20 and improve self-esteem and well-being.21 According to theories of risk communication,22 parent communication should convey harms of IT, reduce positive outcomes of IT, express family norms against IT,23–26 instruct on ways to resist pressure to tan, and encourage healthy alternatives to IT. Communication also may help keep mothers informed about their teen’s IT behavior, if daughters disclose their desire to indoor tan and social pressure to go tanning during mother-daughter conversations.

In this paper, analyses are reported that tested the persisting outcomes of a campaign over Facebook aimed at mothers to prevent IT by their adolescent daughters. Analyses of the immediate impact of the campaign assessed in a 12-month posttest at the conclusion of the campaign showed that the campaign decreased mothers’ permissiveness for IT by adolescent daughters, increased mother-daughter communication about IT harms and avoidance, increased mothers’ support for prohibitions on minors using IT facilities, and reduced mothers’ intentions to indoor tan but not their IT behavior.27 The following two original hypotheses in the trial were tested in the 18-month post-randomization follow-up data, six months after the campaign’s conclusion:

H1: The social media campaign on IT will significantly reduce (a) mother’s permissiveness regarding their daughter’s IT, (b) their daughter’s perception of maternal permissiveness toward IT, and (c) both mother’s and daughter’s IT relative to the control condition.

H2: A significantly greater number of mothers will support a ban on IT for minors in the intervention group compared to the control condition.

Materials and Methods

The Western Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the University of Connecticut and East Tennessee State University IRBs approved study protocols.

Participants

Mothers with daughters 14–17 years old from 34 U.S. states without laws that prohibited all minors under age 18 from using IT facilities at the time of recruitment were enrolled between May 2017 and June 2018. Of the 34 states, 6 had no restrictions; 2 had age restrictions; 14 required parental permission; and 12 had both age and parental-permission requirements. Other eligibility criteria included: (1) ability to read English, (2) had a Facebook account and viewed it at least weekly, and 3) “friend-ed” the project’s community moderator so they could be added to a private Facebook group. Previous IT behavior in daughters was not required because IT initiation typically occurs in teen years and we were interested in preventing IT initiation, as well as convincing those who were tanning to stop. Initially, we planned to recruit mothers and daughters in schools in Tennessee working with Coordinated School Health coordinators.28 However, when that method was unsuccessful, community-based recruitment methods (e.g., community events or groups and out-calls by a university survey research center) were employed in Tennessee and the design was revised to randomize individual mothers, not mothers clustered by school. Revised statistical power calculations indicated that a sample of 860 was needed to achieve 80% power in the unclustered design, accounting for attrition. To complete recruitment, eligibility was expanded to 33 other states and mothers were recruited from a Qualtrics survey panel. After enrolling each mother, we attempted to enroll their 14- to 17-year-old daughter to complete baseline and follow-up assessments. However, the requirement that daughters’ participate for mothers to enroll was eliminated because: 1) intervention was delivered only to mothers, 2) a primary outcome was mothers’ permissiveness to allow IT by daughters, and 3) requiring daughter enrollment was a substantial recruitment barrier. Mothers provided parental consent for their teen daughters to participate and daughters provided informed assent. If a family had more than one age-eligible daughter, the daughter with the birthdate nearest to enrollment date was selected.

Trial Design

The trial involved a pretest-posttest randomized controlled design with follow-ups at 12- and 18-months post-randomization (trial design and 12-month follow-up was reported elsewhere27). Mothers completed baseline survey online and were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group by the project biostatistician. Mothers were added to the Facebook private group by the projects’ community moderator in which their assigned treatment was delivered. In both groups, mothers viewed a feed of 710 health posts over 12 months in which 16% (n=113) were on IT (intervention) or prescription drug misuse (control) and 84% (n=597) discussed mother-daughter communication and other health topics relevant to teenage girls. Mothers stayed in the group for 12 months. This procedure was intended to maintain mothers’ engagement and create an attention control condition. Study staff were blind to treatment, except for the community moderator and program manager. If mothers who left the Facebook groups, they were contacted and asked to re-join. To further retain mothers, they were notified about upcoming follow-up surveys, and mothers were paid for assessments ($40 for baseline, $20 for 12-month follow-up, and $40 for 18-month follow-up). Daughters did not receive any intervention. Instead, they completed baseline survey and 12-month and 18-month follow-up surveys (compensation=$20, $15, and $25, respectively).

Intervention

As described elsewhere,27 Health Chat was a social media campaign based on an integrated theoretical framework combining principles of social cognitive theory (SCT),29 transportation theory (TT),30 and diffusion of innovation theory (DIT).31 Based on SCT, posts emphasized the social situation (social norms), behavioral capability (knowledge and skills), expectations (risk perceptions), observational learning (illustrated in stories), self-efficacy (for refusing IT invitations and requests), and IT alternatives to IT. Posts provided mothers skills for communicating with teens (i.e., active listening, self-disclosure, and showing empathy). Posts included arguments stressing appearance effects and health risks of IT. Relying on transportation and identification effects in narratives, many posts contained links to stories about risks associated with IT and examples of refusing IT requests.30 To promote engagement with the feed and user-generated content that should provoke social comparison processes.32 Posts included current events (e.g., news stories) and cited public figures and invited mothers to react to (e.g., like) and comment on posts (e.g., fill-in-the-blank, quizzes, and questions) Messages were reviewed by investigators, pretested, and refined for aesthetics, clarity, and engagement.

The treatment – IT (intervention group) or prescription drug misuse (control group) – was delivered in approximately 16% of posts, which were posted 2–3 times per week. The remaining 84% of posts addressed mother-daughter communication, health topics relavent to female teens (i.e., mental health, vaccinations, substance use, healthy lifestyle behaviors, media literacy, and parenting), and current events, which mothers indicated were high-interest to them.33 The purpose of IT posts was to: (1) make mothers aware of state IT policy and teens interest in and reasons for IT, (2) increase mothers’ knowledge of the risks linked to IT, 3) increase their self-efficacy to deny daughters’ requests to indoor tan, 4) have mothers model tanning avoidance, 6) describe alternatives to IT such as spa treatments and sunless tanning,34 and 7) convince mothers not to tan and instead practice sun protection. Content was developed from published literature, IT interventions,34–37 government and non-profit organization messages (e.g., CDC, Skin Cancer Foundation, etc.), and public service announcements and news stories. Investigators recorded and posted a series of video where mothers and professionals talked about the harms of IT and ways to improve mother-daughter communication. Preventing prescription drug misuse was used as the control topic because it was (a) not associated with tanning and (b) of interest to mothers. These posts were created working with East Tennessee State University’s Addiction Science Center.

The Health Chat campaign was delivered over Facebook in two private groups, one containing IT posts and another, prescription drug misuse posts. The private group function prevented contamination by restricting posts, comments, and reactions to members of the group. Campaign messages were posted two times a day during a 12- month period. The rate for posting was the result of efforts to deliver enough content to influence but avoid message fatigue. Initially, 25% of posts targeted IT and prescription drug misuse. However, after about six months, engagement declined and mothers commented about over-emphasis on these two topics, suggesting fatigue. Thus, we reduced frequency of experimental posts and increased their currency by linking to news items and seasonal issues. Every two weeks, research staff sent a newsletter by email to participants featuring the popular recent posts. A community moderator scheduled posts, tracked reactions and comments, replied to questions, and addressed misinformation.

Measures

Primary Outcomes.

Mothers’ permissiveness toward IT by daughters and IT behavior at baseline and follow-up and mother’s backing for more restrictions on IT by minors, were the primary outcomes. Permissiveness was assessed with 4 questions with Likert responses (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) on permitting (I would allow my daughter to use a tanning bed; I think it’s OK for my daughter to use a tanning bed; α=0.93) and facilitating daughter’s IT (I would pay for my daughter to tan at a tanning salon; I would take my daughter to a tanning salon to use a tanning bed; α=0.96).36 Daughters also evaluated their mothers’ permissiveness on similar items (permit α=0.91; facilitate α=0.95).35 Mothers noted whether they had given written permission for their daughter to indoor tan in the previous year.

IT behavior by mothers and daughters was measured as the number of times they reported using a tanning bed or booth between December and March, the annual “season” with the highest IT.38 Responses were dichotomized as any use vs. no use, because IT was very infrequent. Similar measures have been validated against diary measures.39 Intention to indoor tan in the next 3 months/6 months/12 months was reported by mothers and daughters (α=0.97 for mothers; α=0.96 for daughters).

Investigators created questions assessing mothers’ backing for prohibiting IT by minors. Mothers indicated the youngest age that they thought their state should prohibit minors from IT. Responses were dichotomized as at or under age 18. Mothers were asked whether they would take seven steps to support a prohibition (yes v. no): voting for a state representative who supports a ban, signing a petition to the state legislature to pass a ban, creating and sharing an online petition, writing a letter to, calling, or speaking with her elected state representative at a local event asking her/him to support a ban, and testifying to a state legislative committee in support of a ban (summed count range=0–7 “yes” responses, α=0.86).

Secondary Outcomes.

Theoretical mediators of campaign effects were assessed. Mothers and daughters reported whether they communicated about seven topics on avoiding IT and harms of IT (e.g., not being pressured to IT and ways that UV radiation can damage a person’s appearance (summed count α=0.84 for mothers; α=0.85 for daughters). Mothers’ self-efficacy to resist IT requests from daughters was measured with a single item. Daughters’ self-efficacy to say no to opportunities to indoor tan with peers was assessed with three items (5-point ratings, α=0.82). Positive and negative attitudes toward IT were assessed by three 5-point Likert-type items each (e.g., I feel favorable about IT; If I were to indoor tan regularly, my skin is likely to wrinkle; mothers: positive attitudes α=0.94, negative attitudes α=0.92; daughters: positive attitudes α=0.95, negative attitudes α=0.90). Daughters indicated if their mothers were tried to know and actually knew about their IT behavior (treated as individual items).

Covariates.

Possible covariates were measured, including age of mother and daughter, their skin phenotypes40 and mother-daughter communication satisfaction (Overall, I am satisfied with the way my daughter and I communicate; 5-point Likert item).41 History of skin cancer for self and family and political ideology (Local government has a responsibility to protect community health by educating people about how to stay healthy and avoid disease; 5-point Likert item) were reported by mothers. Other health behaviors covered in the social media posts were measured with 17 items.

Statistical Analysis

Effects of the intervention were tested employing an intent-to-treat approach. A series of structural equation models (SEM) were calculated using Mplus Version 8.4 – one for each outcome. Variable of interest were assessed for both mother and daughter and a single model was fit that permitted mother and daughter responses to correlate. All multi-item constructs were specified in the SEM as latent variables.42 Outcome(s) in each SEM was regressed on binary treatment indicator (0=control, 1=intervention), baseline value of the outcome(s), intention to indoor tan in the next 12 months (mother and daughter). While balanced at baseline, covariates were included that might predict outcomes, i.e., age of mother and daughter, communication quality, skin phenotype, skin cancer history, political ideology of the mother, state law on parental consent for IT by minors, and source of sample). A full-information robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator for continuous outcomes or weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator with a probit link for categorical outcomes were used to test model fit (see Table 2). For each outcome, unstandardized effect of treatment (difference between intervention and control groups) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (two-tailed) were calculated, as well as the standardized effect of treatment for continuous outcomes. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons as all outcomes were specified a priori. All mothers and daughters were analyzed because missing data on endogenous variables were handled in Mplus by default. For missing data on exogenous control variables, predictive means matching was used in the R package mice to impute 25 datasets, all models were fit using these 25 imputed datasets, and results were combined using Rubin’s rules.43

Table 2:

Means, unstandardized coefficients [95% confidence interval], and standardized estimates for outcomes among mothers by treatment group at posttest

| Indoor Tanning Posts (Intervention) | Prescription Drug Misuse Posts (Control) | Overall | Unstandardized Coefficient | ß3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=342 | n=344 | n=686 | |||

| Mother permits daughter to indoor tan | 1.79 (1.02) | 1.98 (1.09) | 1.89 (1.06) | −0.17 (p=0.016) [−0.31, −0.03] | −0.16 |

| Mother facilitates daughter indoor tanning | 1.55 (1.01) | 1.70 (1.02) | 1.63 (1.02) | −0.11 (p=0.110) [−0.23, 0.02] | −0.11 |

| Mother provided written permission for daughter to indoor tan | 4.4% | 5.0% | 4.7% | −0.03 (p=0.864) [−0.42, 0.35] | NA |

| Mother’s indoor tanning behavior (any use vs. no use) | 14.3% | 14.9% | 14.6% | −0.22 (p=0.314) [−0.66, 0.21] | NA |

| Mother’s intention to indoor tan in the future | 1.55 (1.41) | 1.69 (1.62) | 1.62 (1.52) | −0.18 (p=0.034) [−0.35, −0.01] | −0.13 |

| Mother’s report of daughter’s indoor tanning behavior | 9.4% | 9.3% | 9.3% | −0.12 (p=0.681) [−0.71, 0.46] | NA |

| Mother’s support for indoor tanning ban for minors (<18 years old) | 72.8% | 66.0% | 69.4% | 0.23 (p=0.033) [0.02, 0.43] | NA |

| Mother’s willingness to take advocacy actions for complete ban of indoor tanning by minors1 | 3.19 (2.42) | 2.99 (2.42) | 3.09 (2.42) | 0.07 (p=0.298) [−0.06, 0.21] | 0.09 |

| Mother’s report on mother-daughter communication about indoor tanning2 | 4.11 (2.33) | 3.51 (2.37) | 3.81 (2.37) | 0.20 (p=0.003) [0.07, 0.34] | 0.24 |

| Mother’s self-efficacy to refuse daughter’s request to indoor tan | 4.58 (0.73) | 4.39 (0.89) | 4.49 (0.81) | 0.17 (p=0.002) [0.06, 0.29] | 0.21 |

| Mother’s beliefs about positive aspects of indoor tanning | 1.84 (1.02) | 2.08 (1.08) | 1.96 (1.05) | −0.21 (p=0.001) [−0.33, −0.09] | −0.20 |

| Mother’s beliefs about negative consequences of indoor tanning | 4.56 (0.75) | 4.51 (0.82) | 4.53 (0.79) | 0.08 (p=0.182) [−0.04, 0.20] | 0.10 |

Number of political actions mothers would take to support a ban on indoor tanning by minors (possible range=0 to 7); asked at posttest only.

Number of topics mother discussed with daughter (possible range=0 to 7)

ß=standardized estimate; standardized estimate for binary outcomes are not provided.

Results

Profile of Samples

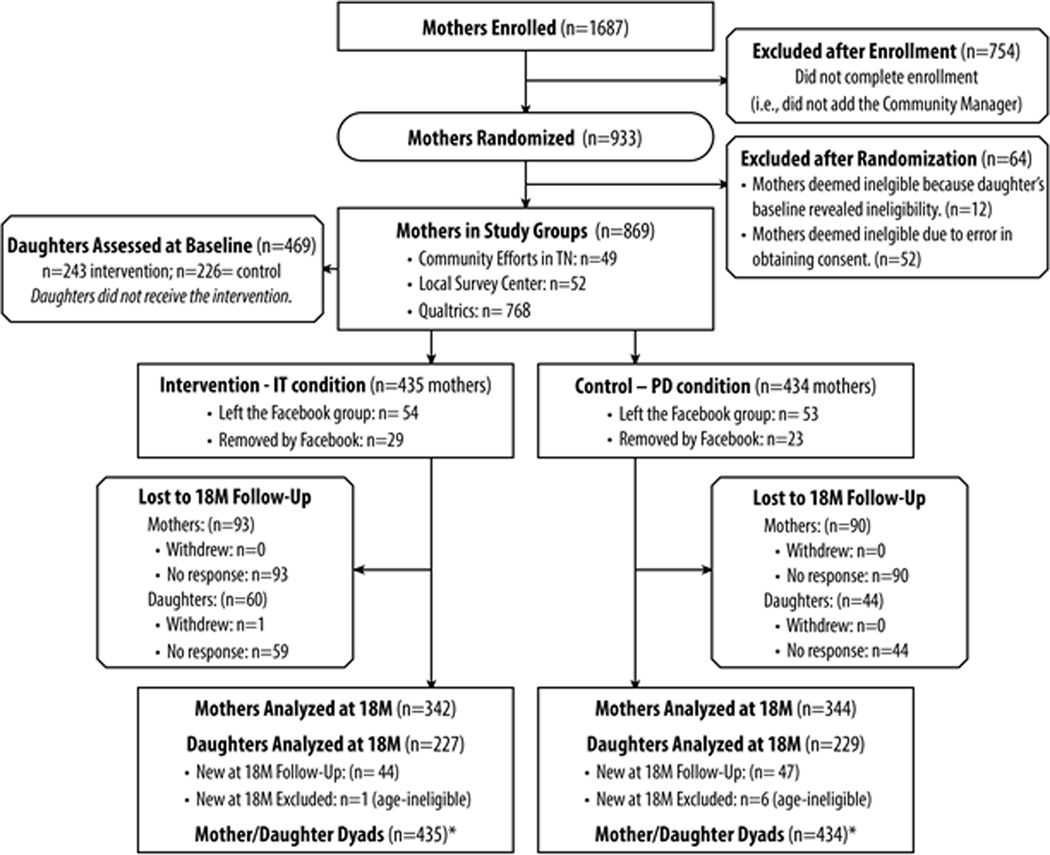

Initially, 869 mothers were enrolled and 469 daughters of participating mothers completed the baseline survey (see Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram) The characteirstics of the mothers and daughters were reported previously.27 As planned, most mothers were non-Hispanic White, the racial group with the highest skin cancer incidence.44 Other ethnic groups were included because public policy requires broad support and skin type does not perfectly align with ethnicity. Mothers were middle aged, 57.8% had a college education, and over half had household incomes of $80,000 or higher. Most mothers said their health was good, very good, or excellent. However, about one in four had skin phenotypes at high risk for melanoma and a one in three had a history of skin cancer in their family. Mothers had diverse political beliefs, but they had a strong belief that government has a responsibility to protect community health. Several of mothers’ health behaviors were similar to national norms. Daughters were similar to mothers on ethnicity, skin type, and many health behaviors, but they reported less use of substances, higher physical activity, and lower obesity.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for randomized trial with 18-month follow-up

*Strutural Equation Models were fit at the level of at the dyad.

Differences Between Treatment Conditions in Mothers

The SEM testing the hypotheses demonstrated adequate fit (Table 1). Hypothesis 1 was partially supported for mothers (Table 2). Relative to controls at posttest, mothers in the intervention group had lower permissivenesss toward IT by daughters, were more likely to communicate with daughters about IT harms and avoidance, and had higher self-efficacy for refusing daughters’ request to indoor tan. Intervention-group mothers had lower IT intentions and expressed less positive attitudes toward IT than control-group mothers. Mothers in the two groups did not express differences in facilitation of daughters’ IT, giving permission for IT by daughters, negative beliefs about IT, or their own IT behavior. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, the social media campaign significantly increased mothers’ backing for prohibitions on IT by minors (Table 2); however, it did not affect the steps they were willing to take to advocate for a complete ban.

Table 1:

Fit statistics for structural equation models1

| Model | Estimator2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s indoor tanning permissiveness scale (permits and facilitates indoor tanning)3 | MLR | 0.979 | 0.959 | 0.037 |

| Mother provided written permission for daughter to indoor tan3* | WLSMV | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Indoor tanning behavior3* | WLSMV | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Indoor tanning intentions3 | MLR | 0.995 | 0.992 | 0.016 |

| Partner’s report of indoor tanning behavior3* | WLSMV | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mother’s supports for indoor tanning ban for minors (<18 years old)* | WLSMV | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mother’s willingness to take advocacy actions for complete ban of indoor tanning by minors | WLSMV | 0.974 | 0.961 | 0.052 |

| Mother-daughter communication about indoor tanning3 | WLSMV | 0.971 | 0.966 | 0.030 |

| Mother’s self-efficacy to refuse daughter’s request to indoor tan* | MLR | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Daughter’s self-efficacy to refuse friends request to indoor tan | MLR | 0.962 | 0.925 | 0.034 |

| Beliefs about positive and negative aspects of indoor tanning3 | MLR | 0.975 | 0.964 | 0.028 |

| Daughter’s perception of mother’s monitoring of their indoor tanning (mother tries to know and really knows)* | MLR | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Fit statistics included Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

MLR=full-information robust maximum likelihood estimator for continuous outcomes; WLSMV=Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance Adjusted (WLSMV) estimator with a probit link for categorical outcomes.

Analysis of mother and daughter reports at the level of the mother-daughter dyad.

Just identified models (no latent variables) fit the data perfectly.

Differences Between Treatment Conditions in Daughters

Daughters whose mothers were in the IT social media group expressed lower positive attitudes toward IT than daughters whose mothers were in the control condition (Table 3). The remaining daughter-level outcomes, including IT behavior, showed no differences between intervention and control groups.

Table 3:

Means, unstandardized coefficients [95% confidence interval], and standardized estimates for outcomes among daughters by treatment group at posttest

| Indoor Tanning Posts (Intervention) | Prescription Drug Misuse Posts (Control) | Overall | Unstandardized Coefficient | ß3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=227 | n=229 | n=456 | |||

| Daughter’s perception that mother permits daughter to indoor tan | 2.02 (1.16) | 2.09 (1.14) | 2.06 (1.15) | −0.10 (p=0.233) [−0.26, 0.06] | −0.09 |

| Daughter’s perception that mother facilitate daughter indoor tanning | 1.75 (1.11) | 1.82 (1.13) | 1.79 (1.12) | −0.04 (p=0.662) [−0.19, 0.12] | −0.03 |

| Daughter’s report that mother provided written permission for daughter to indoor tan | 4.9% | 5.7% | 5.3% | −0.003 (p=0.991) [−0.49, 0.49] | NA |

| Daughter’s indoor tanning behavior (any use vs. no use) | 12.7% | 12.2% | 12.4% | −0.06 (p=0.868) [−0.75, 0.63] | NA |

| Daughter’s intention to indoor tan in the future | 1.75 (1.62) | 1.71 (1.49) | 1.73 (1.56) | 0.02 (p=0.878) [−0.19, 0.22] | 0.01 |

| Daughter’s perception of mother’s indoor tanning behavior | 11.1% | 9.3% | 10.2% | 0.16 (p=0.643) [−0.52, 0.85] | NA |

| Daughter’s report of mother-daughter communication about indoor tanning1 | 3.70 (2.40) | 3.34 (2.35) | 3.52 (2.38) | 0.11 (p=0.168) [−0.05, 0.27] | 0.13 |

| Daughter’s self-efficacy to refuse friends request to indoor tan | 5.50 (1.72) | 5.42 (1.72) | 5.46 (1.72) | 0.03 (p=0.797) [−0.20, 0.25] | 0.02 |

| Daughter’s beliefs about positive aspects of indoor tanning | 2.14 (1.14) | 2.28 (1.12) | 2.21 (1.13) | −0.16 (p=0.043) [−0.31, −0.01] | −0.14 |

| Daughter’s beliefs about negative consequences of indoor tanning | 4.31 (0.76) | 4.29 (0.79) | 4.30 (0.78) | −0.01 (p=0.925) [−0.15, 0.13] | −0.01 |

| Daughter’s perception of mother’s monitoring of their indoor tanning (mother tries to know) | 2.13 (0.87) | 2.11 (0.84) | 2.12 (0.86) | −0.04 (p=0.609) [−0.19, 0.11] | −0.05 |

| Daughter’s perception of mother’s monitoring of their indoor tanning (mother really knows) | 2.61 (0.69) | 2.59 (0.68) | 2.60 (0.68) | −0.01 (p=0.870) [−0.14, 0.11] | −0.02 |

Number of topics mother discussed with daughter (possible range=0 to 7)

ß=standardized estimate; standardized estimate for binary outcomes are not provided.

p<0.05

Discussion

The social media campaign produced a persisting reduction in mothers’ permissiveness toward IT by their daughters, a primary campaign target, six months after the campaign ended, as it had at the campaign’s immediate conclusion.27 Mothers also felt more confident in refusing requests from daughters to indoor tan (i.e., had greater self-efficacy). The campaign delivered messaging to mothers repeatedly over a year, intermixed with content of high relevance and interest to them. Also, the use of narratives featuring mothers and adolescent and young adult daughters complemented didactic messaging that emphasized evidence connecting IT with skin cancer, especially melanoma. Further, mothers’ opinions may have been stablized through users’ interactions with one another through reactions and comments,45 which could stimulate a social comparison process31,32 and cause them to persist for six months following the campaign.

The changes produced by the campaign may improve effectiveness of public policies requiring parental permission for minors to use IT facilities. Mothers’ less positive attitudes toward IT and their lower intentions to indoor tan should have reinforced their reduced permissiveness. Mothers are important gatekeepers of daughters’ tanning behaviors and appearance-related information. Their reduced permissiveness may help to prevent indoor tanning by reducing daughters’ desire for a tan, keeping them from visiting salons, and/or preventing daughters who do attend a salon from accessing the tanning beds, as long as proprietors follow the laws and require permission. It also may reduce daughters’ use of non-salon, unsupervised tanning beds, such as in gyms, apartment buildings, and homes,46,47 which current policy restrictions might not impact. Empirically-based interventions have had strong effects on adolescents’ tanning behaviors7–10; however, they have suffered from an inability to be disseminated broadly. Social media may have broad reach as mothers can impact their other children and diffuse information on IT harms and avoidance to other mothers through their social networks. The latter, while not tested in this study, would be intriguing to explore in future work.

The campaign did not affect daughters’ IT intentions or behaviors. Daughters had low IT intentions at baseline, which would predict low IT behavior in the future, possibly resulting in less opportunity for mothers’ reduced permissiveness to influence them. There had been no differences by experimental condition in daughters’ IT behavior in the 12-months posttest, too. Daughters also were unaware of mothers’ lower permissiveness toward IT in the intervention group. Intervention-group daughters also did not report that the greater mother-daughter communication about IT continued in the six months after the campaign, even though they had reported more communication at the 12-month follow-up than control-group daughters. 27 Continued efforts may be needed to make mother-daughter conversations on IT persist. In a recent trial, a dating violence intervention affected parent-teen son communication initially but not long-term, except among boys who had started dating.48 Daughters in our study may not have initiated IT yet or engaged in it only sporadically, so they were unlikely to request that mothers give permission to indoor tan following the campaign, giving mothers few chances to talk about and refuse IT. Other skin cancer prevention interventions have increased parent-child communication.49,50 For instance, an intervention intended to improve parent-adolescent communication increased sun protection outcomes, including decreasing sunbathing.51 Increased family discussions and changes in sun protection following genetic counseling were reported in another study.52 Finally, participation by daughters in the study was not optimal which affected the study’s power to detect effects among daughters.

The campaign persisted in elevating backing for state bans on minors using IT facilities. Bans have reduced prevalence of IT behavior.2,53,54 It is estimated that bans would avert 240,000 melanoma and 7.3 million keratinocyte skin cancers in North America, saving US$31.1 billion in health care and productivity costs, and 204,000 melanomas and 2.4 million keratinocyte skin cancers in Europe, saving €21.1 billion (US$15.9 billion).55 Social media has been used by citizens to facilitate collective action,56,57 heightening awareness of and framing issues, developing advocacy networks, and motivating online and offline collective actions.56–58 This trial suggested that a social media campaign delivering theory-based messages on preventing IT by adolescent daughters to mothers can obtain their support for prohibitions on IT by minors in the U.S. policy context.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had both strengths and limitations. The prospective randomized controlled design, use of theories, low burden of a private Facebook group which prevented treatment contamination, and diverse samples of mothers and daughters from 34 states were strengths. Limitations include reliance on an Internet-based survey panel, when community-based recruitment had limited success. Such panels can be biased toward more affluent, educated adults and those with Internet access. However, Qualtrics panel samples may have fewer biases than samples from other online panels.59 Just over half of the daughters completed assessments, which reduced power for daughter-level outcomes. Private Facebook groups do not allow users to share posts with their Facebook friends network. Self-report measures might be considered a limitation, but they were practical with a remotely-recruited sample and are appropriate for assessing internal cognitions, which may not be measurable in other ways.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Social media occupy an prominent place in parents’ media diet. Well-crafted social media posts embedded in a general newsfeed on adolescent health may affect parents and possibly their children. Parents can play an essential role in public policies on child health. Often, policy enforcement is limited and profit motives or negligence of businesses cause them to flout the policy. Social media messaging that convinces parents to be less permissive toward IT could make parental permission laws more successful by setting expectations that teens will not use tanning beds or convince mothers to withhold permission for IT when teens request it. Social media also may garner support for further restrictions to decrease melanoma in young adult women.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01CA192652 received by D.B. Buller, S. Pagoto, K.L. Henry, K. Baker, B.J. Walkosz, and J. Hillhouse. All of the total project costs (100%; $3,282,739) were financed with Federal money. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Buller receives a salary from Klein Buendel, Inc., and his spouse is an owner of Klein Buendel, Inc. Dr. Walkosz, Ms. Berteletti, and Ms. Kinsey receive a salary from Klein Buendel, Inc. Dr. Pagoto, Dr. Henry, Dr. Baker, Dr. Hillhouse, and Ms. Bibeau have nothing to declare.

Clinical Trials Registration Information: The ClinicalTrials.gov registration number is NCT02835807.

References

- 1.Holman DM, Jones SE, Qin J, Richardson LC. Prevalence of indoor tanning among U.S. high school students from 2009 to 2017. J Community Health. 2019;44(6):1086–1089. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00685-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez-Acevedo AJ, Green AC, Sinclair C, van Deventer E, Gordon LG. Indoor tanning prevalence after the International Agency for Research on Cancer statement on carcinogenicity of artificial tanning devices: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(4):849–859. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgard B, Schope J, Holzschuh I, et al. Solarium Use and Risk for Malignant Melanoma: Meta-analysis and Evidence-based Medicine Systematic Review. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(2):1187–1199. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandini S, Dore JF, Autier P, Greinert R, Boniol M. Epidemiological evidence of carcinogenicity of sunbed use and of efficacy of preventive measures. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33 Suppl 2:57–62. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho H, Yu B, Cannon J, Zhu YM. Efficacy of a media literacy intervention for indoor tanning prevention. J Health Commun. 2018;23(7):643–651. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1500659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blashill AJ, Rooney BM, Luberto CM, Gonzales Mt, Grogan S. A brief facial morphing intervention to reduce skin cancer risk behaviors: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Body Image. 2018;25:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Scaglione NM, Cleveland MJ, Baker K, Florence LC. A web-based intervention to reduce indoor tanning motivations in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci. 2017;18(2):131–140. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0698-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stapleton J, Turrisi R, Hillhouse J, Robinson JK, Abar B. A comparison of the efficacy of an appearance-focused skin cancer intervention within indoor tanner subgroups identified by latent profile analysis. J Behav Med. 2010;33(3):181–190. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9246-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, Robinson J. A randomized controlled trial of an appearance-focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3257–3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillhouse JJ, Turrisi R. Examination of the efficacy of an appearance-focused intervention to reduce UV exposure. J Behav Med. 2002;25(4):395–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pew Research Center. Social Media Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/. Published June 12 2019. Accessed October 1, 2021.

- 12.Reimann J, McWhirter JE, Papadopoulos A, Dewey C. A systematic review of compliance with indoor tanning legislation. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1096. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5994-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stryker JE, Lazovich D, Forster JL, Emmons KM, Sorensen G, Demierre MF. Maternal/female caregiver influences on adolescent indoor tanning. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):528-525e521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magee KH, Poorsattar S, Seidel KD, Hornung RL. Tanning device usage: what are parents thinking? Pediatric Dermatol. 2007;24(3):216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cokkinides V, Weinstock M, Lazovich D, Ward E, Thun M. Indoor tanning use among adolescents in the US, 1998 to 2004. Cancer. 2009;115(1):190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker MK, Hillhouse JJ, Liu X. The effect of initial indoor tanning with mother on current tanning patterns. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(12):1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazovich D, Choi K, Rolnick C, Jackson JM, Forster J, Southwell B. An intervention to decrease adolescent indoor tanning: a multi-method pilot study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):S76–S82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Dittus P, Bouris AM. Parental expertise, trustworthiness, and accessibility: Parent-adolescent communication and adolescent risk behavior. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68(5):1229–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00325.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luk JW, Farhat T, Iannotti RJ, Simons-Morton BG. Parent-child communication and substance use among adolescents: do father and mother communication play a different role for sons and daughters? Addict Behav. 2010;35(5):426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson HW, Donenberg G. Quality of parent communication about sex and its relationship to risky sexual behavior among youth in psychiatric care: a pilot study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):387–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00229.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson S, Bijstra J, Oostra L, Bosma H. Adolescents’ perceptions of communication with parents relative to specific aspects of relationships with parents and personal development. J Adolesc. 1998;21(3):305–322. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: the extended parallel process model. Commun Monogr. 1992;59(4):329–349. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18(3):203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carcioppolo N, Peng W, Lun D, Occa A. Can a social norms appeal reduce indoor tanning? Preliminary findings from a tailored messaging intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(5):818–823. doi: 10.1177/1090198119839105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carcioppolo N, Orrego Dunleavy V, Myrick JG. A closer look at descriptive norms and indoor tanning: Investigating the intermediary role of positive and negative outcome expectations. Health Commun. 2019;34(13):1619–1627. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1517632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carcioppolo N, Orrego Dunleavy V, Yang Q. How do perceived descriptive norms influence indoor tanning intentions? An application of the theory of normative social behavior. Health Commun. 2017;32(2):230–239. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2015.1120697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buller DB, Pagoto S, Baker K, et al. Results of a social media campaign to prevent indoor tanning by teens: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med Rep. 2021;22:101382. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pagoto S, Baker K, Griffith J, et al. Engaging moms on teen indoor tanning through social media: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e228. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green MC. Narratives and cancer communication. J Commun. 2006;56(1):S163–S183. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suls JM, Miller RL. Social Comparison Processes. New York, NY: Hemisphere; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker K, Pagato S, Buller D, et al. A mixed methods approach to designing a social media intervention for mothers of adolescent girls in Tennessee. Paper presented at: Society of Behavioral Medicine 38th Annual Meeting & Scientific Sessions; March 29 - April 1, 2017; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Oleski J, Bodenlos JS, Ma Y. The sunless study: a beach randomized trial of a skin cancer prevention intervention promoting sunless tanning. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(9):979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker MK. Preventing skin cancer in adolescent girls through intervention with their mothers. Dissertation. Johnson City, TN: Department of Public Health, East Tennessee State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Cleveland MJ, Scaglione NM, Baker K, Florence LC. Theory-driven longitudinal study exploring indoor tanning initiation in teens using a person-centered approach. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(1):48–57. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9731-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mays D, Zhao X. The influence of framed messages and self-affirmation on indoor tanning behavioral intentions in 18- to 30-year-old women. Health Psychol. 2016;35(2):123–130. doi: 10.1037/hea0000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hillhouse J, Stapleton J, Turrisi R. Association of frequent indoor UV tanning with seasonal affective disorder. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(11):1465–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visser P, King L, Hillhouse J. Accuracy of one- and three-month recalls for indoor tanning. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine; March 26–29, 2008; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berwick M, Armstrong BK, Ben-Porat L, et al. Sun exposure and mortality from melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(3):195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child Dev. 1985;56(2):438–447. doi: 10.2307/1129732 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borsboom D. Latent variable theory. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives. 2008;6(1–2):25–53. doi: 10.1080/15366360802035497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rate of new cancers: melanomas of the skin. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Web site. Available at: https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html. Published 2019. Accessed October 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Himelboim I, Xiao X, Lee DKL, Wang MY, Borah P. A social networks approach to understanding vaccine conversations on Twitter: network clusters, sentiment, and certainty in hpv social networks. Health Commun. 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1573446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pagoto SL, Conroy DE, Arroyo K, et al. Assessment of tanning beds in 3 popular gym chains. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1918058. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18058.PMC6991224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hillhouse J, Stapleton JL, Florence LC, Pagoto S. Prevalence and correlates of indoor tanning in nonsalon locations among a national sample of young women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1134–1136. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizzo CJ, Houck C, Barker D, Collibee C, Hood E, Bala K. Project STRONG: an online, parent–son intervention for the prevention of dating violence among early adolescent boys. Prev Sci. 20201;22:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01168-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards T, Mkwanazi N, Mitchell J, Bland RM, Rochat TJ. Empowering parents for human immunodeficiency virus prevention: Health and sex education at home. South Afr J HIV Med. 2020;21(1):970. doi: 10.4102/sajhivmed.v21i1.970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sutton MY, Lasswell SM, Lanier Y, Miller KS. Impact of parent-child communication interventions on sex behaviors and cognitive outcomes for black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino youth: a systematic review, 1988–2012. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(4):369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turrisi R, Hillhouse J, Heavin S, Robinson J, Adams M, Berry J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent-based intervention to prevent skin cancer. J Behav Med. 2004;27(4):393–412. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBM.0000042412.53765.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu YP, Aspinwall LG, Parsons B, et al. Parent and child perspectives on family interactions related to melanoma risk and prevention after CDKN2A/p16 testing of minor children. J Community Genet. 2020;11(3):321–329. doi: 10.1007/s12687-020-00453-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reimann J, McWhirter JE, Cimino A, Papadopoulos A, Dewey C. Impact of legislation on youth indoor tanning behaviour: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2019;123:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qin J, Holman DM, Jones SE, Berkowitz Z, Guy GP Jr. State Indoor Tanning Laws and Prevalence of Indoor Tanning Among US High School Students, 2009–2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(7):951–956. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gordon LG, Rodriguez-Acevedo AJ, Køster B, et al. Association of indoor tanning regulations with health and economic outcomes in North America and Europe. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(4):401–410. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCaughey M, Ayers MD. Cyberactivism: Online Activism in Theory and Practice. Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hefler M, Freeman B, Chapman S. Tobacco control advocacy in the age of social media: using Facebook, Twitter and Change. Tob Control. 2013;22(3):210–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo C, Saxton GD. Tweeting social change: how social media are changing nonprofit advocacy. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 2014;43(1):57–79. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boas TC, Christenson DP, Glick DM. Recruiting large online samples in the United States and India: Facebook, Mechanical Turk, and Qualtrics. Political Sci Res Methods. 2020:8(2):232–250. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2018.28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]