Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells targeting CD19 mediate potent anti-tumor effects in B cell malignancies including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), but antigen loss remains the major cause of treatment failure. To mitigate antigen escape and potentially improve durability of remission, we developed a dual-targeting approach using an optimized, bispecific CAR construct that targets both CD19 and BAFF-R. CD19-BAFF-R dual CAR T cells exhibited antigen-specific cytokine release, degranulation and cytotoxicity against both CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/− variant human ALL cells in vitro. Immunodeficient mice engrafted with mixed CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/− variant ALL cells and treated with a single dose of CD19-BAFF-R dual CAR T cells experienced complete eradication of both CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/− ALL variants, while mice treated with monospecific CD19 or BAFF-R CAR T cells succumbed to outgrowths of CD19-/BAFF-R+ or CD19+/BAFF-R- tumors, respectively. Further, CD19-BAFF-R dual CAR T cells showed prolonged in vivo persistence, raising the possibility that these cells may have potential to promote durable remissions. Together, our data support clinical translation of BAFF-R/CD19 dual CAR T cells to treat ALL.

Keywords: CD19/BAFF-R dual CAR T cells, ALL, chimeric antigen receptor, adoptive cellular therapy

Introduction

Clinical trials evaluating CD19-targeting chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have resulted in overall response rates of up to 90% in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)(1–3) and 50–80% in lymphoma(4–7). Despite initial responses, antigen negative relapse is common following CD19-targeted therapies(8–11), and may occur in up to 39% of patients(9, 12, 13). One approach of addressing this problem is to utilize dual-targeting CAR T cells, a strategy that has recently been applied to CD19/CD22(14) for ALL, CD19/CD20 for B cell malignancies(15, 16) and CD19/BCMA(17), CS1/BCMA(18) and BCMA/GPRC5D(19) for multiple myeloma. Dual-targeting CARs simultaneously target two antigens and, therefore, potentially eradicate heterogenous tumors. Dual-targeted CAR T cells are expected to provide greater tumor coverage than single-targeted therapy, potentially circumventing antigen escape. Moreover, if one tumor antigen becomes downregulated during treatment, the second targeting domain will continue to be reactive to tumors. Therefore, it is critical to identify novel targets that can be combined with CD19 in a dual-targeted immunotherapeutic platform.

We previously developed CAR T cell therapy against a novel target, B-cell activating factor receptor (BAFF-R), based on the remarkable specificity of anti-BAFF-R antibodies that we generated(20). BAFF-R is expressed almost exclusively on B cells, including in patients with CD19-negative relapse(21–25), making it an ideal immunotherapeutic target. Limited studies suggest that BAFF-R is a critical regulator of B-cell function and survival, which may mitigate the tumor’s ability to escape therapy through antigen loss, particularly if a non-redundant role for BAFF-R is confirmed(22, 26, 27). BAFF-R-CAR T cells demonstrate in vitro effector function and in vivo therapeutic efficacy in CD19-negative models, including patient-derived xenograft models(25), and are currently being evaluated clinically for treatment of ALL (NCT04690595). We hypothesized that simultaneous targeting of CD19 and BAFF-R in a bispecific CAR platform could confer a therapeutic advantage and avoid the challenges of sequential administration of CD19 and BAFF-R monospecific CAR T cells.

We leveraged our experience with CD19- and BAFF-R-CAR T cells to develop a dual-targeting, bispecific CAR T cell platform (CD19/BAFF-R dual CAR T cells). We identified the optimal orientation of single chain variable fragment (scFv) domains and tested our optimized dual CAR construct using different populations of T cells. We demonstrated that CD19/BAFF-R dual CAR T cells potently eradicate ALL both in vitro and in a NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull (NSG) mouse model of heterogenous (CD19−/−and BAFF-R−/−) leukemia.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

Nalm-6 and HL-60 cells were obtained in 2015 from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany) and maintained in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Hyclone, Logan, Utah, USA). Nalm-6 cells were transduced with a lentivirus encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein and firefly luciferase (EGFP-ffluc). GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS and single cell clones were expanded. Z138 cells were provided by Dr. Michael Wang (MD Anderson Cancer Center). Cell lines were authenticated for desired antigen/marker expression by flow cytometry before cryopreservation.

Nalm-6-BAFF-R-knockout (KO) and Nalm-6-CD19-KO cell lines were developed previously(25). Briefly, we used CD19-CRISPR/Cas9 or BAFF-R-CRISPR/Cas9 and RFP reporter genes containing homologous directed repair Plasmid Systems (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. We transfected plasmids with Neon Electroporation Transfection System (Thermo Fisher) as follows: Voltage: 1350V, Pulse Width: 35 ms, Pulse Number: 1. CD19- and BAFF-R-negative cells were sorted by FACS and single cell clones were expanded. The same approach was used to generate CD19-KO Z138 cells. Stable CD19- and BAFF-R-deficient clones were verified by flow cytometry and immunoblotting before banking.

Primary ALL cells were obtained from City of Hope (COH) Hematopoietic Tissue Bank under protocols approved by COH Institutional Review Board. Samples were depleted of CD3+ cells using the Human CD3 Positive Selection kit (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada Cat#:17851) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, 5×106 cells were incubated with 10μL selection cocktail/100μL cell suspension for 10 minutes, incubated with 6μL Dextran RapidShere beads for 3 minutes at room temperature and applied to EasySep magnets (Stemcell Technologies Cat#: 18000) for 3 minutes. CD3+ cells were eliminated by negative selection. Unbound cells were evaluated with anti-CD3 antibodies (BD Biosciences Cat#: 563109) using MACSQuant (Miltenyi Biotec) and FCS express flow cytometry software (version 7).

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry

To assess lentiviral transduction, T cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti-EGFR (clone AY13; BioLegend, San Diego, California, USA). To assess degranulation, T cells were incubated with anti-CD107a APC (clone H4A3; BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) at 37°C for 6 hours in medium containing Golgi plug (BD Biosciences). Stimulated cells were washed with buffer and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti-CD4 Pacific Blue (clone PRA-T4), anti-CD8 APC-Cy7 (clone SK1), anti-CD10 PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone HI10a) (BD Biosciences) and anti-EGFR PE (clone AY13) (BioLegend). To detect tumor and CAR T cells in mice, 30–50 μl blood was collected 46–50 days post-tumor engraftment, and red blood cells were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (BD Biosciences). Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti-CD3 Pancific Blue (UCHT1), anti-CD10 PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone HI10a), anti-CD19 APC (clone HIB19), anti-BAFF-R BUV395 (clone 11C1) (BD Biosciences) and anti-EGFR PE (clone AY13) (BioLegend), and stained with fixable viability dye (BD Biosciences). To detect BAFF-R and CD19, cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti-CD19 APC (clone HIB19), anti-BAFF-R APC (clone 11C1) or APC isotype (clone MOPC-21) (BD Biosciences).

Data was acquired on a BD Fortessa and analyzed using Flowjo Version 10 software. CAR T cells were GFP+ or EGFR+. Activated CD4 and CD8 cells from degranulation assays were CD4+ EGFR+ CD107a+ and CD8+ EGFR+ CD107a+, respectively. CAR T cells in mouse blood were CD3+EGFR+; tumor cells were CD10+ GFP+ CD19+ or CD10+ GFP+ BAFF-R+.

CAR constructs and lentiviral production

We generated monospecific CAR constructs using research and clinical vectors. Research constructs were scFv (BAFF-R: humanized H90 BAFF-R antibody scFv(20); CD19: FMC63 CD19 monoclonal antibody(28)), CD8 transmembrane, 4–1BB co-stimulatory, and CD3ζ intracellular signaling domains. CAR cDNAs were cloned into pLenti7.3 lentiviral vector (pLenti7.3/V5-TOPO Vector Kit, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) under the CMV promoter; constructs contained GFP under the SV40 promoter. Clinical constructs were scFv (BAFF-R: humanized H90 BAFF-R antibody scFv(20); CD19: FMC63 CD19 monoclonal antibody(28)), CD4 transmembrane domain, co-stimulatory domain (BAFF-R: 4–1BB; CD19: CD28), CD3ζ intracellular signaling domains and truncated EGFR (EGFRt)(29), for final constructs of BAFF-RCAR:4–1BB:ζ/EGFRt(30) and CD19CAR:CD28:ζ/EGFRt(31).

BAFF-R/CD19 dual CARs were as follows: for tandem CARs, BAFF-R and CD19 scFvs were fused with G4S linker in one of two orientations (CD19:BAFF-R:4–1BB:ζ/EGFRt [CD19-BAFFR(t)] and BAFF-R:CD19:4–1BB:ζ/EGFRt [BAFF-R-CD19(t)]); for the loop CAR, CD19(VL):BAFF-R(VH):BAFF-R(VL):CD19(VH):4–1BB:ζ/EGFRt [CD19-BAFFR(l) were fused with whitlow linker(32). All constructs included CD4 transmembrane domain, the 229-amino acid, double-mutated IgG4 Fc spacer (L235E; N297Q)(31), 4–1BB co-stimulatory and CD3ζ signaling domains, and EGFRt separated by a T2A ribosomal skip sequence(29). Constructs were cloned into an epHIV7 lentiviral backbone under the EF1a promoter. For lentiviral production, 14×106 293T cells transfected with plasmids encoding CARs and packaging and envelop vectors (PCHGP2, pCMV-Rev, pCMV-G) with 3μg PEI (Polysciences, Warrington, Pennsylvania, USA) per 1μg of DNA in T-225 flasks. Supernatant collected 48–96 hours later was concentrated by centrifuging 6080xg overnight at 4°C.

CAR T cell production protocol (research)

CAR T cells were produced using our research-grade protocol(25) for indicated experiments. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were obtained from the Michael Amini Transfusion Medicine Center at COH (IRB: 15283). CD8 and/or CD8 T naïve cells were isolated from PBMCs with Human Naïve CD8+ or Naive T Cell Isolation Kits, respectively (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). T cells were cultured in vivo-15 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% human serum (Valley biomedical, Winchester, Virginia, USA) and 100U/mL human IL-2, and activated with Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 beads (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA) for 24 hours before transduction with lentivirus at MOI 1. Cultures were maintained at 0.5–1×106 cells/mL in medium containing 100 U/mL IL-2. After 7 days, CD3/CD28 beads were removed by Dynamag-2. GFP-positive single CAR T cells or EGFR-positive dual CAR T cells were enriched by FACS, activated and expanded with CD3/CD28 bead stimulation for another 7 days. CD3/CD28 beads were removed by Dynamag-2 before use. T cells from each donor were used to produce un-transduced T-cell controls (mock) in parallel to CAR T cells.

CAR T cell production protocol (cGMP)

CAR T cells were produced using a cGMP production protocol(30) for indicated experiments. Leukapheresis products were obtained from healthy donors using protocols approved by the COH Institutional Review Board (IRB: 15283). Blood from different healthy donors was used for each experiment as indicated. Naïve and central memory T cells (Tn/mem) were defined as CD62L+CD14-CD25- and isolated by Miltenyi AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Briefly, PBMCs were incubated with anti-CD14 and anti-CD25 microbeads and CD14+and CD25+ cells were immediately depleted. The unlabeled fraction was incubated with anti-CD62L microbeads and CD62L+ cells were purified with positive selection. Isolated Tn/mem or Tn cells were activated, transduced, and expanded for 14 days as described with 50U/mL IL2 and 0.5ng/mL IL15(30, 33).

In vitro functional assays

We measured chromium-51 (51Cr) release to calculate specific lysis of tumor cells as described(25). Briefly, CAR T (105) cells were co-incubated with 51Cr-labeled target cells (104) in 96-well V-bottom tissue culture plates for 4 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. 51Cr was detected in clarified supernatant by gamma counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Specific Lysis(%)=(CPM-SR/MR-SR)x100%, where CPM is sample count per minute, SR is CPM of spontaneous release, and MR is CPM of maximum release(34).

Degranulation was assessed by measuring CD107a-positivity by flow cytometry, as described(25). Briefly, target cells (2×105) were co-incubated with 105 CAR T cells in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing Golgi Stop Protein Transport Inhibitor (BD Bioscience) and anti-CD107a APC (BioLegend) for 6 hours. Cells were analyzed on BD Flow cytometer. To measure INF-γ release, 2×105 CAR T cells were co-cultured in 96-well U-bottom tissue culture plates with 2×105 target cells at 37°C in 5% CO2. Supernatants harvested 24 hours post-stimulation were analyzed in triplicate by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using human IFN-γ uncoated ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher).

In vivo modeling

NSG mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and maintained by the Animal Resource Center at COH. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility according to institutional guidelines. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC: 15020). NSG mice (12–16 week old female; 5/group for statistical power) were challenged (IV) with luciferase-expressing tumor cells followed by treatment with CAR T cells(25). Mock T cell or PBS-treated mice were controls. Tumors were monitored by bioluminescent imagining. Briefly, mice were challenged with 2.5×105 Nalm-6-BAFF-R-KO + 1×105 Nalm-6-CD19-KO or 1×105 Nalm-6-BAFF-R-KO + 1×105 Nalm-6-CD19-KO where indicated. 9–10 days post-tumor challenge, mice were assessed for engraftment and randomly allocated to treatment groups. A single infusion of 2.5×106 CD4 T cells + 1×106 of CD8 T cells of dual-targeting CAR T cells or 1×106 BAFF-R/CD19 dual CAR, CD19 or BAFF-R single CAR-T cells as indicated, were administered intravenously. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and received subcutaneous d-luciferin (150 mg/kg; Life Technologies) 10 minutes before imaging with LagoX imaging systems (Spectral Instruments Imaging, Tucson, Arizona, USA). Investigators were not blinded to group allocation or outcome assessment.

Statistical analysis

Means±SD of triplicate samples are presented. Paired Student’s t-tests were used to compare experimental and control groups. Experiments were repeated with T cells from at least three different donors. Survival data was reported in Kaplan-Meier plots and analyzed by log-rank tests.

Results

Dual CAR T cells showed activity against heterogeneous ALL

To optimize a dual targeting platform, we adapted the BAFF-R and CD19 scFv domains from our single targeting platforms(30, 35) to generate 3 CAR constructs that combine the dual-scFv domains in tandem (t) or loop (l) configurations (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 1A). We transduced naïve CD8+ T cells with single or dual constructs (Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 1B), and evaluated potency of purified GFP+ (≥80%) single or EGFR-enriched (≥92%) dual CAR T cells by chromium-release assays. We chromium-51 labeled the ALL cell line Nalm-6 wildtype (WT), as well as Nalm-6 cells that were deficient of either CD19 (CD19−/−) or BAFF-R(25) (BAFF-R−/−) (Figure 1C), and incubated with CAR T cells or un-transduced (mock) cells at a 10:1 effector-to-target ratio (E:T). As expected, CD19- and BAFF-R single CAR T cells induced cytotoxicity of Nalm-6 WT cells and BAFF-R−/− and CD19−/− cells, respectively, and did not induce cytotoxicity of CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/−, respectively (Figure 1D). CD19-BAFF-R(t) and CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells exhibited specific cytotoxicity against all target cells (P<0.001), suggesting that cytotoxicity was induced from both scFvs (Figure 1D). Specific cytotoxicity was equivalent between dual and single-targeting CAR T cells. BAFF-R-CD19(t) CAR T cells, which differ from CD19-BAFF-R(t) in scFv orientation, exhibited inferior cytotoxicity against Nalm-6 CD19−/− (BAFF-R+) target cells (Supplemental Figure 1C), suggesting that in this orientation the BAFF-R scFv cannot optimally target BAFF-R. Therefore, we subsequently evaluated only CD19-BAFF-R(t) and CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR constructs.

Figure 1. Development of prototype BAFF-R/CD19 dual-targeting CAR T cells.

A. Schematics depict the arrangement of BAFF-R and CD19 targeting scFvs designed for each dual-targeting CAR construct. B. Human CD8 naïve cells from healthy human donors were enriched, activated and transduced with lentiviral vector encoding 4–1BB costimulatory molecules and GFP for single CAR or EGFR for dual CAR. After 7 days in vitro expansion, GFP+ or EGFR+ CAR T cells were enriched and expanded for another 7 days before functional assay. FACS analysis plots show CAR positive T cells following enrichment. CAR reporter genes were gated on T cells: GFP-positive single-targeting CAR T cells (top panel); EGFR positive dual CARs (lower panel). C. FACS histogram show BAFF-R or CD19 expression in Nalm-6 ALL tumor lines, including wild-type, CD19−/−, and BAFF-R−/− variants. Cells were stained by BAFF-R-APC, CD19-APC or isotype control antibodies. D. Calculated specific lysis are plotted from a cytotoxicity assay against Nalm-6 ALL tumor lines, including wild-type (WT), CD19−/−, and BAFF-R−/− at 10:1 of E:T ratios. Effector CAR T cells were CD19-BAFF-R(t) and CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-targeting CARs and BAFF-R and CD19 single-targeting CARs. Mock T cells were used as negative control. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed by a Student’s t-test. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, NS: not statistically significant.

To test the function of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in our dual CAR platform, we transduced naïve CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with lentivirus encoding the dual CAR constructs at MOI of 1. Resulting EGFR+ CAR T cells were purified (Figure 2A) and used in cytotoxicity assays targeting Nalm-6 cell lines (WT, CD19−/− or BAFF-R−/−) as previously described. Both CD4+ and CD8+ dual CAR T cells had significantly superior (P<0.01) cytotoxicity against Nalm-6 WT, Nalm-6 CD19−/−, and Nalm-6 BAFF-R−/− targets compared to mock T cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Functional evaluation of CD19/BAFF-R dual-targeting CAR T cells.

Human CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were enriched, activated and transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding CD19-BAFF-R(t) and CD19-BAFF-R(l) CARs separately. After 7 days in vitro expansion, EGFR+ CAR T cells were enriched and expanded for another 7 days before functional analysis. A. FACS analysis plots show CD4 and CD8 CAR positive T cells following the EGFR enrichment. Purity of CAR T cells is depicted. B. Calculated specific lysis are plotted from a cytotoxicity assay against Nalm-6 CD19−/−and Nalm-6 BAFF-R−/− variants at 10:1 E:T ratio. Effector CARs are CD19-BAFF-R(t) and CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-CARs for both CD4 and CD8 CAR T cells. Mock T cells were used as negative control. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed with a Student’s t-test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. C. Bioluminescent imaging of NSG Mice (n=5/group in one experiment) inoculated with mixed tumor (0.1 ×106 Nalm-6-CD19−/− plus 0.25 ×106 Nalm-6-BAFF-R−/−). Mice were administered with a single infusion of 2.5 ×106 CD4 T cells + 1 ×106of CD8 T cells, either CD19-BAFF-R(t) or CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-targeting CAR T cells on day 10. Mock T cells from the same donor were used as control. D. Flux (photons/sec) was determined by measuring bioluminescence every 10–20 days E. Kaplan-Meier survival curve show the results after monitoring mice for up to 90 days. Log-rank test: **p<0.01.

To evaluate antigen-dependent targeting in vivo, we utilized a mixed B-cell leukemia model that simulates clinical tumor heterogeneity. Mice were inoculated with 2.5:1 Nalm-6 BAFF-R−/− and CD19−/− cells, infused with a single injection of either CD19-BAFF-R(t) or CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells and monitored for tumor growth. Mice treated with dual CAR T cells demonstrated significantly delayed tumor growth at day 20 (Figure 2C–D; P<0.01) and had significantly prolonged survival compared to untreated and mock controls (Figure 2E; P< 0.01). Because we observed a significant survival advantage in mice treated with CD19-BAFF-R(l) versus CD19-BAFFR(t) dual CAR T cells (P<0.01), we focused further development on CD19-BAFFR(l) dual CAR T cells.

Tn/mem-derived dual CAR T cells eradicated heterogeneous ALL

To test the CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR in a clinically relevant platform, we utilized a defined memory-enriched T cell population (CD62L+CD14-CD25-; [Tn/mem]) that is currently used in multiple ongoing CAR T cell clinical trials at COH(30). We transduced CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells (MOI=2) and achieved 40% CAR+ cells (Figure 3A). We observed similar expansion in CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells and mock Tn/mem cells after 14 days (Figure 3B). To determine in vitro potency, we incubated CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells with Nalm-6 cells (CD19−/− or BAFFR−/−) at 1:1 or 2:1 E:T and measured IFN-γ release (Figure 3C) and degranulation (Figure 3D), respectively. Neither CD19-BAFFR(l) CAR nor mock T cells released IFN-γ when incubated in media or with control CD19−/−BAFF-R−/− HL-60 cells. However, CD19-BAFF-R(l) CAR T cells released IFN-γ following incubation with Nalm-6 CD19−/− or BAFF-R−/− cells (P<0.001) (Figure 3C). Both CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cell populations degranulated upon stimulation with Nalm-6 CD19−/− or BAFF-R−/− cells, but not when incubated in media or with HL-60 cells (Figure 3D). To determine if CD19-BAFF-R(l) CAR T cells were effective in other B cell malignancies, we conducted cytotoxicity assays using the mantle cell lymphoma cell line Z138 and Z138 cells deficient of CD19 (WT and CD19−/−, respectively). While CD19 monospecific CAR T cells killed Z138 WT cells, dual CAR T cells killed both Z138 WT and CD19−/− cells equivalently (Figure 3E). Together, these data suggest that the in vitro functionality of CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells is antigen specific and that the dual scFv domains recognize their respective antigens independently.

Figure 3. Antitumor activity of CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-targeting CAR T cells manufactured in a clinically relevant platform.

A. Naïve and central memory T cells (Tn/mem) were enriched, activated and transduced, and expanded for 14 days. Growth curve plots the expansion of CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells. Non-transduced T cells (Non-CAR) were isolated from the same donor and cultured in parallel. B. FACS analysis of CAR transduction efficiency of CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-CAR T cells at MOI=2. Samples were analyzed at the end of CAR production on day 14 and analyzed with anti-EGFR-APC antibody. C. Bar Graph shows ELISA measurements of IFN-γ released by CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells. Dual CAR T cells were co-cultured for 24 hours with either BAFF-R−/− or CD19−/− Nalm-6 B-ALL cell lines at 10:1 E:T ratio. IFN-γ was measured from sampled supernatant by ELISA. Mock T cells from the same donor and irrelevant HL-60 cell line were used as controls. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed by a Student’s t-test; ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, NS: not statistically significant. D. FACS plots of CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T-cell functional potency as measured by a CD107a degranulation assay. 19-BAFFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells were co-incubated with either BAFF-R−/− or CD19−/− Nalm-6 B-ALL cell lines. Non-transduced T cells from the same donor (Non-CAR) and irrelevant HL-60 cell line were used as controls. Percentages of CD107a from gated CD4 and CD8 CAR are presented. E. Specific lysis induced by CAR T cells against Z138 MCL tumor lines, including wild-type (WT) and CD19−/− at 10:1 of E:T ratios. Effector CAR T cells were CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-targeting and CD19 single-targeting CARs. Mock T cells were used as negative control. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed by a Student’s t-test. ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01. F. Bioluminescent imaging of NSG Mice (n=5/group in one experiment) challenged with mixed tumor (0.1 × 106 Nalm-6-CD19−/− plus 0.1 × 106 Nalm-6-BAFF-R−/−). Mice were administered with a single infusion (1 × 106 CAR T cells) of CD19-BAFF-R (l) dual-targeting CAR T cells on day 9. Mock T cells at the respective total dose levels (Mock, 2.5 × 106 T cells) from the same donor were used as control. G. Flux (photons/sec) was determined by measuring bioluminescence every 10–20 days. H. Kaplan-Meier survival curve show the results after monitoring mice for up to 100 days. Log-rank test: **p<0.01, between CD19-BAFF-R (l) CAR and Mock T cells.

To validate the in vivo functional potency of Tn/mem-derived CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells, we treated mice bearing mixed leukemia (1:1 of Nalm-6 CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/−) with mock T cells, dual CAR T cells or PBS. We decreased the ratio of BAFFR−/− and CD19−/− cells in our mixed leukemia model from 2.5:1 (Figure 2) to 1:1 to assess complete tumor clearance and long-term survival. Consistent with naïve-derived CAR T cells (Figure 2), 1×106 Tn/mem-derived dual CAR T cells completely eradicated tumors and significantly prolonged mouse survival (Figure 3E–G) compared to untreated and mock treated mice (P<0.01). Thus, for subsequent in vivo experiments, we utilized the dosing strategy of 1×106 CAR-positive T cells.

Dual but not monospecific CAR T cells eradicated heterogeneous ALL

To compare dual and monospecific CAR T cells, we engineered single-targeting CARs using our clinical lentiviral vectors (BAFF-R/4–1BB:ζ and CD19/28:ζ) and the dual CAR using the CD19-BAFF-R(l)/41BB:ζ vector. For a direct comparison, we manufactured all CAR T cells in parallel using Tn/mem cells from the same healthy donor (Supplemental Figure 2). We observed that monospecific and dual CAR T cells possessed stronger in vitro effector functions against target cell lines expressing their specific target antigens than mock T cells (P<0.001) (Figure 4A–B). Monospecific CAR T cells possessed stronger effector functions than dual CAR T cells as indicated by increased degranulation (P<0.01; Figure 4A) and IFN-γ secretion (P<0.01; Figure 4B) following target cell stimulation. This difference could result from differential configuration of scFv domains that may lead to different antigen affinity and strength of signaling. To elucidate whether CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells are effective in the context of high disease burden, we conducted cytotoxicity assays using E:T of 10:1, 2:1, and 0.5:1. We observed a dose dependent decrease in cytotoxicity induced by dual and monospecific CAR T cells against target cells expressing their respective target antigen(s) (Figure 4C). Notably, killing by both dual and monospecific constructs was proportional at each E:T, suggesting that dual CAR T cells did not lose potency in the context of high disease burden. When we treated mice engrafted with 1:1 Nalm-6 CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/− with monospecific or dual CAR T cells, we observed superior tumor eradication (P<0.01; Figure 4D–E) and survival (P<0.01; Figure 4F) by dual CAR T cells compared to either single-targeting CAR and mock T cells. Together, these results suggest that dual targeting may improve efficacy and mitigate antigen-escape against heterogeneous leukemia.

Figure 4. Comparison of CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-targeting CAR with CD19 and BAFF-R single CAR in a mixed tumor model.

A. Naïve and central memory T cells (Tn/mem) cells were enriched, activated, transduced, and expanded for 13 days. FACS analysis plots CD107a positive CD4 or CD8 CAR T cells (CAR gated) comparing CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR, BAFF-R single CAR, and CD19 single CAR degranulation against Nalm-6 CD19−/−BAFF-R+/+ and Nalm-6 CD19+/+BAFF-R−/− B-ALL lines. Mock T cells from the same donor were used as a control. B. Graph shows ELISA measurements of IFN-γ released by CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells compared to BAFF-R and CD19 single CAR T cells. CAR T cells were co-incubated with either BAFF-R−/− or CD19−/− Nalm-6 B-ALL lines. IFN-γ was measured from sampled supernatant. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed by a Student’s t-test; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, NS: not statistically significant. C. Specific lysis induced by CAR T cells against Nalm-6 WT, BAFF-R−/− or CD19−/− Nalm-6 B-ALL cell lines. Effector CAR T cells were CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-targeting CARs and BAFF-R and CD19 single-targeting CARs at 10:1, 2:1, and 0.5:1 E:T ratios. Mock T cells were used as negative control. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed by a Student’s t-test. ****P<0.0001, ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, NS: not statistically significant. D. Bioluminescent imaging of NSG Mice (n=5/group in one experiment) challenged with mixed tumor (0.1 ×106 Nalm-6-CD19−/− plus 0.1 ×106 Nalm-6-BAFF-R−/−). Mice were administered a single infusion of (1 × 106 CAR T cells), BAFF-R, CD19 single-targeting CAR T cells or CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual-targeting CAR T cells on day 9. Mock T cells from the same donor were used as control. E. Flux (photons/sec) was determined by measuring bioluminescence every two weeks. F. Kaplan-Meier survival curve show the results after monitoring mice for up to 100 days. Log-rank test: **p<0.01, between dual CAR and CD19, BAFF-R single CAR.

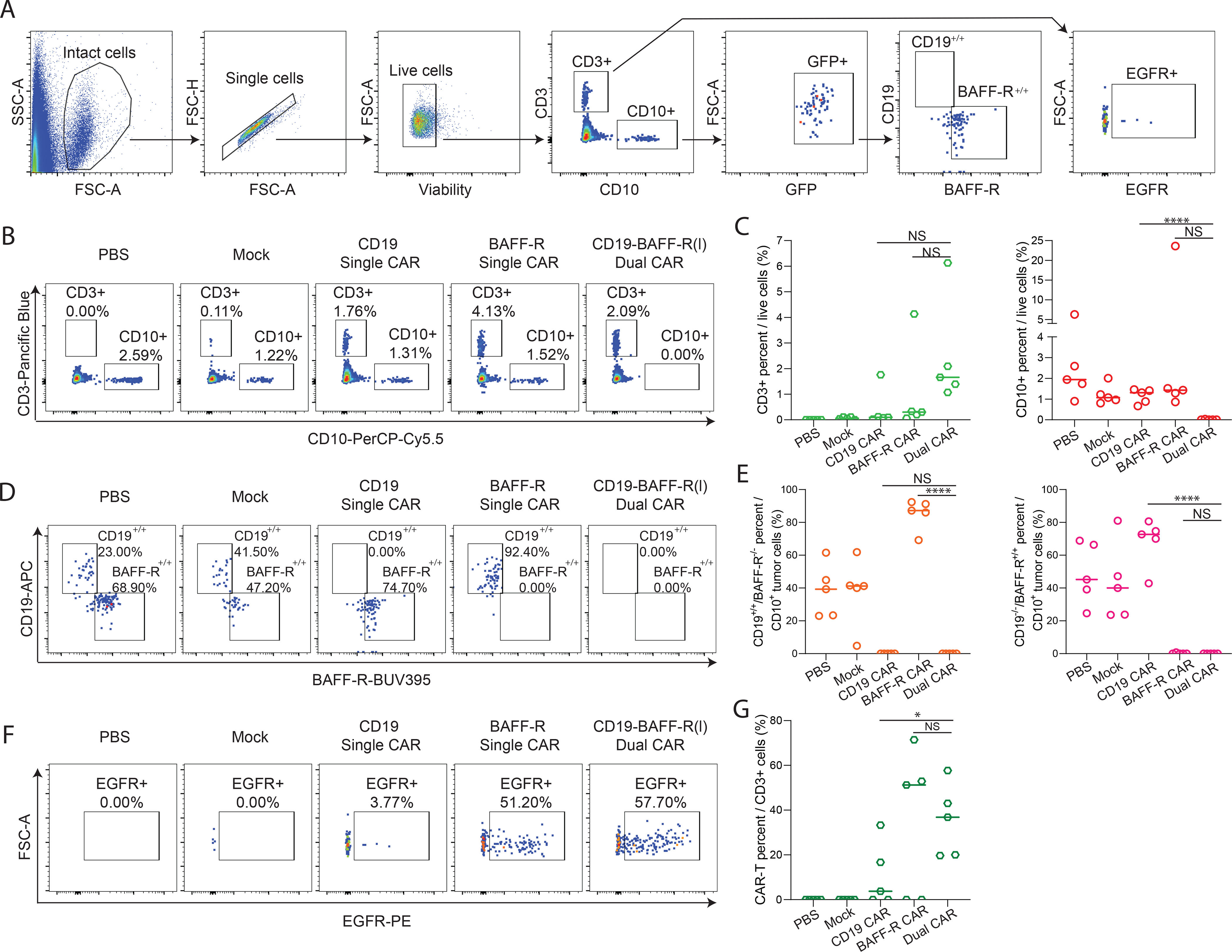

To characterize tumors post-CAR T cell therapy, we analyzed blood from mice 46–50 days post tumor inoculation. We observed a significant reduction in CD10+ leukemic cells in mice treated with dual versus monospecific CD19CAR T cells (P<0.0001) (Figure 5A–C). Tumor cells isolated from mice treated with CD19 or BAFF-R single CAR T cells were negative for CD19 or BAFF-R, respectively, demonstrating effective tumor elimination in a target-dependent manner (Figure 5D). CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells completely eradicated both CD19+ and BAFF-R+ tumors (P<0.001) (Figure 5D–E), supporting the dual targeting feature of these cells. We detected equivalent levels of CAR T cells in mice treated with BAFF-R CAR T cells and CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells, but significantly more in mice treated with CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells than in CD19 CAR T cell-treated mice (P<0.05), despite full tumor clearance in dual CAR T cell-treated mice (Figure 5F–G). Overall, this data suggests that CD19-BAFFR(l) dual CAR T cells have potential for long-term in vivo persistence and expansion.

Figure 5. Analysis of residual tumor and CAR T cells in mouse peripheral blood.

Blood was collected 46–50 days post tumor challenge and analyzed with multicolor flow cytometry. A. FACS plots depict the gating strategy used to identify CAR-T and tumor cells in mouse peripheral blood. Viable singlets were gated for CD3+ EGFR+ CAR-T cells and CD10+ tumor cells. B. FACS plots of CD3+ T cell or CD10+ tumor cells in PBS, Mock, CD19 Single CAR, BAFF-R Single CAR and CD19-BAFF-R (l) Dual CAR treated mouse blood. One mouse is displayed as representative of each cohort. C. The dot graph shows the cumulative data of CD3+ T cell or CD10+ tumor cells from five mice in each cohort. Data were analyzed by a Student’s t-test; ****P<0.0001, NS, not significant. D. Lineage analysis of tumor cells for CD19 and BAFF-R expression based off CD10 gating in PBS, Mock, BAFF-R single CAR, CD-19 single CAR, and CD19-BAFF-R(l) Dual CAR groups. E. Cumulative data of CD19 and BAFF-R expression from five mice in each cohort are presented. Data were analyzed by a Student’s t-test; ****P<0.0001, NS, not significant. F. Percentages of CAR (EGFR) T cells from CD3 gate are depicted from one representative mouse. FACS analysis plots from one representative mouse are displayed for each cohort. E. Cumulative data of CAR T cells from 5 mice per cohort are presented. Data were analyzed by a Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, NS: not statistically significant.

Dual CAR T cells can target heterogeneous primary ALL cells

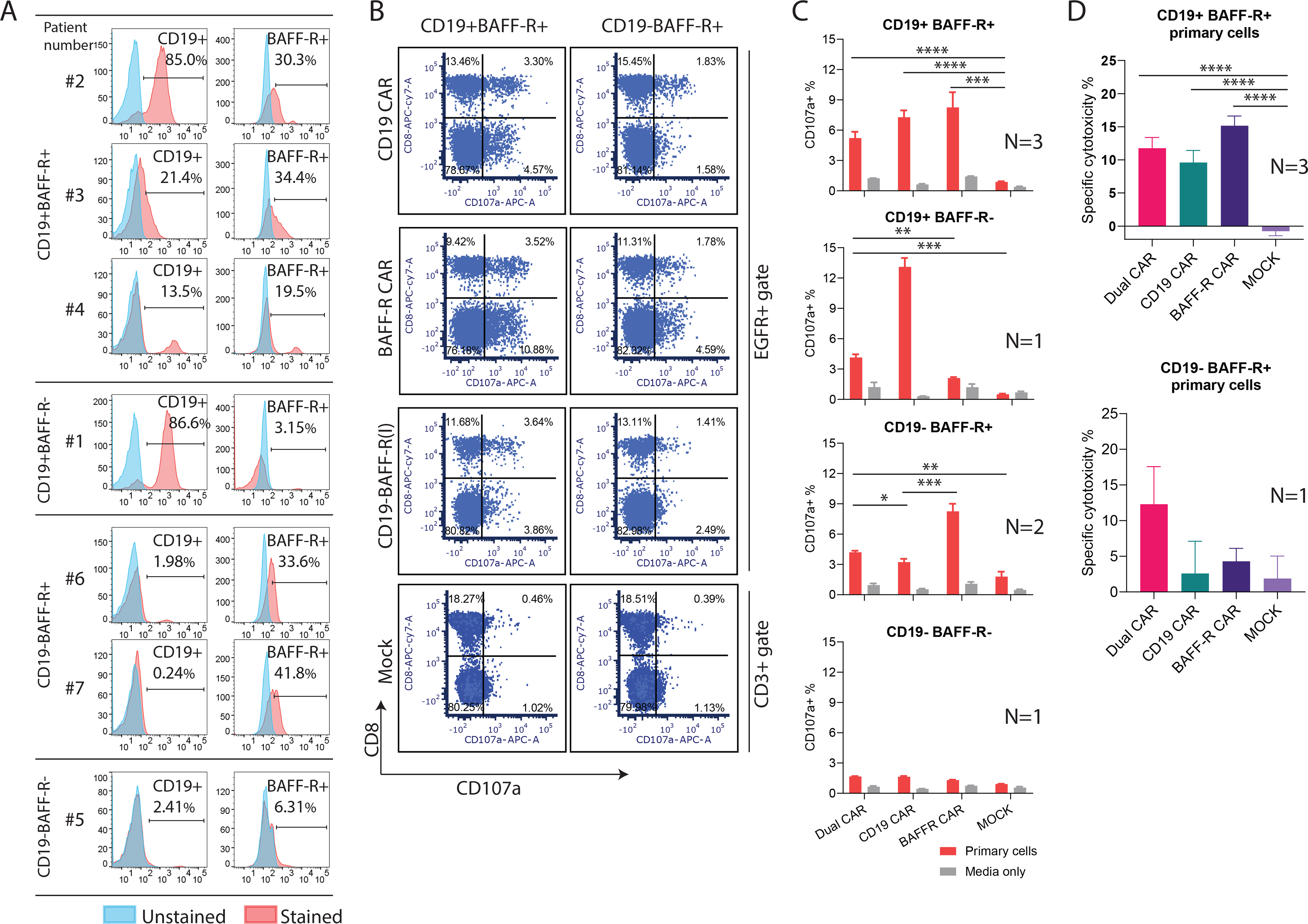

To evaluate targeting of primary ALL cells by dual CAR T cells, we performed cytotoxicity (51Cr) and degranulation as in Figures 2 and 4, respectively, using CD19+ and CD19 primary ALL samples (Figure 6A) as targets. We depleted T cells from patient samples before performing the assays to avoid any reaction of patient-derived T cells and healthy donor-derived CAR T cells (Supplemental Figure 3). Dual and monospecific CAR T cells degranulated (Figure 6B–C) and induced cytotoxicity (Figure 6D) against primary ALL cells that express their target antigen.

Figure 6. Dual CAR T cells exhibited efficient cytotoxicity against primary ALL cells.

A. Seven blood samples from patients with ALL were collected and CD19 and BAFF-R expression were analyzed with flow cytometry. N=3 for CD19+BAFF-R+; N=1 for CD19+BAFF-R-; N=2 CD19-BAFF-R+; N=1 for CD19+BAFF-R+. B-C. T cell-depleted patient samples were co-cultured with BAFF-R and CD19 monospecific or CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells at 1:2 ratio for 6 hours. CD107a expression was analyzed with flow cytometry. Representative data of CD107a expression under EGFR (CAR) gated population and accumulative data are presented. Experiments were conducted in triplicate for each patient specimen. D. Specific lysis of CAR T cells against primary ALL cells. Effector CAR T cells were CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual or BAFF-R and CD19 monospecific CAR T cells at 10:1 E:T. Mock T cells were used as negative control. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed by a Student’s t-test. ****P<0.0001, ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05, NS: not statistically significant.

Discussion

CD19 CAR T cell therapy has achieved high response rates in ALL(1–3) and lymphoma(4–7), but CD19-negative relapse compromises its potential success(3, 36, 37). We optimized a dual-targeting CAR T cell platform with potential to mitigate antigen escape and increase durability of remission. We leveraged our experience targeting BAFF-R(20, 22, 23, 25) to design CD19-BAFF-R dual CAR T cells (Figure 1), which showed potent effector function against heterogeneous target cells in vitro (Figure 1–4) and extended survival in our mouse model of heterogeneous ALL (Figure 2–4). Furthermore, CD19-BAFF-R dual CAR T cells persisted in mice following tumor elimination (Figure 5), suggesting that they may hold potential for inducing long term remissions.

Dual targeting may prevent antigen loss post-CAR T cell therapy. Bispecific CAR constructs have advantages over sequential or simultaneous co-administration of monospecific CAR T cells, which can be inefficient and costly. Designing a dual CAR is challenging, and a panel of constructs is typically needed to systemically evaluate the effects of orientation of the two scFv domains relative to each other on function of resulting dual CAR T cells; the best candidate construct will equivalently execute effector function in vitro and in vivo against both targets. We evaluated 3 CD19/BAFF-R dual CAR constructs that differed in scFv orientation (Figure 1; Supplemental Figure 1). When transduced into T cells, only CD19-BAFFR(t) and CAR CD19-BAFFR(l) yielded effective dual targeting in vitro (Figure 1; Supplemental Figure 1). This data agrees with previous studies showing that scFv orientation can alter antigen binding and targeting(38). However, in other reports, modification of linker/spacers within the CAR construct(39) or generating a biscistronic structure(40) are also necessary to achieve dual targeting.

CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells exhibited the best anti-ALL activity in our in vivo mixed leukemia mouse model (Figure 2), and were successfully manufactured using current clinical and research platforms that use Tn/mem cells(30, 33). We confirmed that dual CAR engineering did not compromise cell expansion as indicated by comparable growth to mock T cells (Figure 3A). CD19-BAFF-R(t) and CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CARs conferred both CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells the capability to induce cytotoxicity against target cells. Although they exhibited similar effector function in vitro (Figure 3D), CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells exhibited better antitumor activity in vivo (Figure 3E–F). It is possible that in our model CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells may meet the higher requirement for antigen-induced activation that is influenced by antigen and receptor density and affinity of interaction(41–44).

We compared the anti-ALL activity of dual and monospecific CAR T cells (Figures 4–5). As expected, we observed superior antitumor activity of CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells over monospecific CD19 and BAFF-R CAR T cells, which led to significantly improved mouse survival. These data suggest that CD19-BAFF-R(l) dual CAR T cells eradicate both CD19+ and BAFFR+ tumors, while monospecific CD19 and BAFF-R CAR T cells can only target their respective antigens. Monospecific CD19 CAR T cells were not able to control CD19-negative tumors, indicating that CD19 CAR T cells would not be capable of controlling CD19-negative relapsed ALL. Therefore, we hypothesize that dual targeting may prevent relapse of ALL by superior clearance of heterogeneous tumors.

Tissue harvests confirmed that dual CAR T cells completely eradicated CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/− ALL cells while monospecific CD19 and BAFF-R CAR T cells only controlled respective CD19+ or BAFF-R+ tumors (Figure 5). Dual CAR T cells exhibited better persistence in vivo than monospecific CD19 CAR T cells, possibly due to difference in co-stimulatory domains, which may contribute to durable response after infusion. If CD19 is lost, any persisting dual CAR T cells retain tumor targeting capabilities and may potentially prevent antigen escape-driven relapse. While this data is encouraging, the conclusions we can draw are limited by our immunodeficient mouse model and, therefore, will need to be validated in an immunocompetent model.

Our unique CD19-BAFF-R dual-targeting CAR T cells will be the first to target this combination of tumor associated antigens. Our study demonstrated the reliability of bispecific CD19-BAFF-R CAR T cell therapy in inducing remission in ALL consisting of CD19−/− and BAFF-R−/− cell lines and primary ALL cells (Figure 6). Moreover, we anticipate that our CD19-BAFF-R dual-targeting strategy will be applicable to other B cell malignancies. We hypothesize that simultaneous targeting of heterogeneous cancer cell populations may diminish the likelihood of antigen escape and may have significant impact on cancer treatment by improving the therapeutic benefits of CAR T cell therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Small Animal Imaging Core is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (P30CA033572); National Cancer Institute Lymphoma SPORE (PI: L.W.K. and S.J.F.); Toni Stephenson Lymphoma Center (PI: L.W.K.); Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Mantle cell lymphoma Research Initiative (SCOR 7000-18; PI: L.W.K.; Project Leaders: S.J.F.; X.W.; E.L.B.); Department of Defense (CA170783, PI: L.W.K.).

Competing Interests:

Sources of support include the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (P30CA033572) supporting the Small Animal Imaging Core, National Cancer Institute Lymphoma SPORE (PI: L.W.K.), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Mantle cell lymphoma Research Initiative (SCOR 7000-18; PI: L.W.K.; Project Leaders: S.J.F.; X.W.), Department of Defense (CA170783, PI: L.W.K.). X.W. is a paid consultant for Pepromene Bio, Inc.; L.W.K. and H.Q. are paid consultants and have equity in Pepromene Bio, Inc. The other authors report no disclosures.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: X.W. is a paid consultant for Pepromene Bio, Inc.; L.W.K. and H.Q. are paid consultants and have equity in Pepromene Bio, Inc. The other authors report no disclosures.

References

- 1.Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, Bartido S, Park J, Curran K, et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19–28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Sustained Remissions in Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(16):1507–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):517–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maus MV, Grupp SA, Porter DL, June CH. Antibody-modified T cells: CARs take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2014;123(17):2625–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, Somerville RP, Carpenter RO, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):540–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochenderfer JN, Somerville R, Lu L, Iwamoto A, Yang JC, Klebanoff C, et al. Anti-CD19 CAR T Cells Administered after Low-Dose Chemotherapy Can Induce Remissions of Chemotherapy-Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Blood. 2014;124(21):550–. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruella M, Maus MV. Catch me if you can: Leukemia Escape after CD19-Directed T Cell Immunotherapies. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016;14:357–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sotillo E, Barrett DM, Black KL, Bagashev A, Oldridge D, Wu G, et al. Convergence of Acquired Mutations and Alternative Splicing of CD19 Enables Resistance to CART-19 Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(12):1282–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlando EJ, Han X, Tribouley C, Wood PA, Leary RJ, Riester M, et al. Genetic mechanisms of target antigen loss in CAR19 therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1504–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Aldoss I, Qu C, Crawford JC, Gu Z, Allen EK, et al. Tumor-intrinsic and -extrinsic determinants of response to blinatumomab in adults with B-ALL. Blood. 2021;137(4):471–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner R, Wu D, Cherian S, Fang M, Hanafi LA, Finney O, et al. Acquisition of a CD19-negative myeloid phenotype allows immune escape of MLL-rearranged B-ALL from CD19 CAR-T-cell therapy. Blood. 2016;127(20):2406–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagel I, Bartels M, Duell J, Oberg HH, Ussat S, Bruckmueller H, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell involvement in BCR-ABL1-positive ALL as a potential mechanism of resistance to blinatumomab therapy. Blood. 2017;130(18):2027–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin H, Ramakrishna S, Nguyen S, Fountaine TJ, Ponduri A, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Preclinical Development of Bivalent Chimeric Antigen Receptors Targeting Both CD19 and CD22. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2018;11:127–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah NN, Johnson BD, Schneider D, Zhu F, Szabo A, Keever-Taylor CA, et al. Bispecific anti-CD20, anti-CD19 CAR T cells for relapsed B cell malignancies: a phase 1 dose escalation and expansion trial. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong C, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Ji X, Zhang W, Guo Y, et al. Optimized tandem CD19/CD20 CAR-engineered T cells in refractory/relapsed B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2020;136(14):1632–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang L, Zhang J, Li M, Xu N, Qi W, Tan J, et al. Characterization of novel dual tandem CD19/BCMA chimeric antigen receptor T cells to potentially treat multiple myeloma. Biomarker Research. 2020;8(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zah E, Nam E, Bhuvan V, Tran U, Ji BY, Gosliner SB, et al. Systematically optimized BCMA/CS1 bispecific CAR-T cells robustly control heterogeneous multiple myeloma. Nature Communications. 2020;11(1):2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Larrea CF, Staehr M, Lopez AV, Ng KY, Chen Y, Godfrey WD, et al. Defining an Optimal Dual-Targeted CAR T-cell Therapy Approach Simultaneously Targeting BCMA and GPRC5D to Prevent BCMA Escape-Driven Relapse in Multiple Myeloma. Blood Cancer Discov. 2020;1(2):146–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin H, Wei G, Sakamaki I, Dong Z, Cheng WA, Smith DL, et al. Novel BAFF-Receptor Antibody to Natively Folded Recombinant Protein Eliminates Drug-Resistant Human B-cell Malignancies In Vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(5):1114–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodig SJ, Shahsafaei A, Li B, Mackay CR, Dorfman DM. BAFF-R, the major B cell-activating factor receptor, is expressed on most mature B cells and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Hum Pathol. 2005;36(10):1113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hildebrand JM, Luo Z, Manske MK, Price-Troska T, Ziesmer SC, Lin W, et al. A BAFF-R mutation associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma alters TRAF recruitment and reveals new insights into BAFF-R signaling. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207(12):2569–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson JS, Bixler SA, Qian F, Vora K, Scott ML, Cachero TG, et al. BAFF-R, a Newly Identified TNF Receptor That Specifically Interacts with BAFF. Science. 2001;293(5537):2108–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parameswaran R, Lim M, Fei F, Abdel-Azim H, Arutyunyan A, Schiffer I, et al. Effector-mediated eradication of precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a novel Fc-engineered monoclonal antibody targeting the BAFF-R. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(6):1567–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin H, Dong Z, Wang X, Cheng WA, Wen F, Xue W, et al. CAR T cells targeting BAFF-R can overcome CD19 antigen loss in B cell malignancies. Science Translational Medicine. 2019;11(511):eaaw9414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smulski CR, Eibel H. BAFF and BAFF-Receptor in B Cell Selection and Survival. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018;9(2285). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maia S, Pelletier M, Ding J, Hsu YM, Sallan SE, Rao SP, et al. Aberrant expression of functional BAFF-system receptors by malignant B-cell precursors impacts leukemia cell survival. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowolik CM, Topp MS, Gonzalez S, Pfeiffer T, Olivares S, Gonzalez N, et al. CD28 Costimulation Provided through a CD19-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor Enhances In vivo Persistence and Antitumor Efficacy of Adoptively Transferred T Cells. Cancer Research. 2006;66(22):10995–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Chang WC, Wong CW, Colcher D, Sherman M, Ostberg JR, et al. A transgene-encoded cell surface polypeptide for selection, in vivo tracking, and ablation of engineered cells. Blood. 2011;118(5):1255–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Z, Cheng WA, Smith DL, Huang B, Zhang T, Chang W-C, et al. Antitumor efficacy of BAFF-R targeting CAR T cells manufactured under clinic-ready conditions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69(10):2139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonnalagadda M, Mardiros A, Urak R, Wang X, Hoffman LJ, Bernanke A, et al. Chimeric antigen receptors with mutated IgG4 Fc spacer avoid fc receptor binding and improve T cell persistence and antitumor efficacy. Mol Ther. 2015;23(4):757–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fry TJ, Shah NN, Orentas RJ, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan CM, Ramakrishna S, et al. CD22-targeted CAR T cells induce remission in B-ALL that is naive or resistant to CD19-targeted CAR immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2018;24(1):20–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Huynh C, Urak R, Weng L, Walter M, Lim L, et al. The Cerebroventricular Environment Modifies CAR T Cells for Potent Activity against Both Central Nervous System and Systemic Lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9(1):75–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stastny MJ, Brown CE, Ruel C, Jensen MC. Medulloblastomas expressing IL13Ralpha2 are targets for IL13-zetakine+ cytolytic T cells. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;29(10):669–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Popplewell LL, Wagner JR, Naranjo A, Blanchard MS, Mott MR, et al. Phase 1 studies of central memory-derived CD19 CAR T-cell therapy following autologous HSCT in patients with B-cell NHL. Blood. 2016;127(24):2980–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, Aplenc R, Porter DL, Rheingold SR, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor–Modified T Cells for Acute Lymphoid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(16):1509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gökbuget N, Goebeler M, Klinger M, Neumann S, et al. Targeted Therapy With the T-Cell–Engaging Antibody Blinatumomab of Chemotherapy-Refractory Minimal Residual Disease in B-Lineage Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Patients Results in High Response Rate and Prolonged Leukemia-Free Survival. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(18):2493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang K, Geddie ML, Kohli N, Kornaga T, Kirpotin DB, Jiao Y, et al. Comprehensive optimization of a single-chain variable domain antibody fragment as a targeting ligand for a cytotoxic nanoparticle. MAbs. 2015;7(1):42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zah E, Lin MY, Silva-Benedict A, Jensen MC, Chen YY. T Cells Expressing CD19/CD20 Bispecific Chimeric Antigen Receptors Prevent Antigen Escape by Malignant B Cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(6):498–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah NN, Maatman T, Hari P, Johnson B. Multi Targeted CAR-T Cell Therapies for B-Cell Malignancies. Front Oncol. 2019;9:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker AJ, Majzner RG, Zhang L, Wanhainen K, Long AH, Nguyen SM, et al. Tumor Antigen and Receptor Densities Regulate Efficacy of a Chimeric Antigen Receptor Targeting Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase. Mol Ther. 2017;25(9):2189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe K, Terakura S, Martens AC, van Meerten T, Uchiyama S, Imai M, et al. Target Antigen Density Governs the Efficacy of Anti–CD20-CD28-CD3 ζ Chimeric Antigen Receptor–Modified Effector CD8+ T Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2015;194(3):911–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caruso HG, Hurton LV, Najjar A, Rushworth D, Ang S, Olivares S, et al. Tuning Sensitivity of CAR to EGFR Density Limits Recognition of Normal Tissue While Maintaining Potent Antitumor Activity. Cancer Research. 2015;75(17):3505–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turatti F, Figini M, Balladore E, Alberti P, Casalini P, Marks JD, et al. Redirected activity of human antitumor chimeric immune receptors is governed by antigen and receptor expression levels and affinity of interaction. J Immunother. 2007;30(7):684–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.