Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to test the behavior of the case fatality rate (CFR) in a mixed population of vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals by illustrating the role of both the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing deaths and the detection of infections among both the vaccinated (breakthrough infections) and unvaccinated individuals.

Methods

We simulated three hypothetical CFR scenarios that resulted from a different combination of vaccine effectiveness in preventing deaths and the efforts in detecting infections among both the vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

Results

In the presence of vaccines, the CFR depends not only on the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing deaths but also on the detection of breakthrough infections. As a result, a decline in the CFR may not imply that vaccines are effective in reducing deaths. Likewise, a constant CFR can still mean that vaccines are effective in reducing deaths.

Conclusions

Unless vaccinated people are also tested for COVID-19 infection, the CFR loses its meaning in tracking the pandemic. This shows that unless efforts are directed at detecting breakthrough infections, it is hard to disentangle the effect of vaccines in reducing deaths from the probability of detecting infections on the CFR.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine effectiveness, Case Fatality Rate, Breakthrough Infections

Introduction

With an increased testing capacity, vaccination could lead to a decline in the case fatality rate (CFR), because vaccinated individuals may still get infected but develop less severe symptoms than nonvaccinated individuals (Hall et al., 2021). Indeed, if the same testing strategy is maintained before and after vaccines are introduced, a declining CFR would imply that vaccines are preventing deaths. However, we show that the CFR depends not only on the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing deaths among the vaccinated but also on detecting infections among both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Thus, the CFR can either increase, decrease, or remain constant, even if the infection fatality rate of the vaccinated is lower than the infection fatality rate of the unvaccinated. This feature highlights the importance of detecting infections among vaccinated individuals or the so-called breakthrough infections. A vaccine breakthrough infection is defined as the detection of SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid or antigen in a respiratory specimen collected from a person ≥14 days after all recommended doses of a United States Food and Drug Administration authorized COVID-19 vaccine (NNDSS, 2021). As of May 1, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stopped monitoring all reported vaccine breakthrough cases to focus on identifying and investigating only symptomatic breakthrough cases that lead to hospitalization or death (CDC, 2021), despite rising cases in breakthrough infections (Hacisuleyman et al., 2021). According to the CDC, the reason for focusing on breakthrough cases that lead to hospitalization or death is to “maximize the quality of the data collected on cases of greatest clinical and public health importance” (CDC, 2021). The CDC maintained that ongoing support would be provided to state health departments to identify SARS-CoV-2 infections among vaccinated individuals and register them at the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS), but the focus has been on health-care workers and local clusters (Britton, 2021; Keehner et al., 2021).

Understandably, the rationale for focusing on lethal outcomes and hospitalizations stems mainly from the burden of severe symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 on health infrastructure, which pushed health systems to the limit globally (Lal et al., 2021). However, studying all breakthrough infections is not only critical for monitoring real-world vaccine effectiveness against variants and whether they are outsmarting vaccines (Cyranoski, 2021; Mina and Andersen, 2021; Lipsitch et al., 2021) but it is also key for accurately measuring vaccine effectiveness in reducing deaths. We illustrate the latter point by showing how the CFR in the presence of vaccines depends both on the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing deaths among the infected and on the ratio of the detection rates between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated.

By illustrating how the CFR is sensitive to both the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing deaths among the infected and the ratio of the detection rates between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated, we derive two important results. First, we show the effect of undetected positive cases among vaccinated individuals, and consequently, the impact of not tracking all breakthrough infections. Second, we illustrate the behavior of the CFR in a mixed population of vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. This is a contribution to the discussion on how policymakers and other stakeholders should be aware of these effects when using or interpreting these values, as the CFR has already been shown to be dependent on demographic factors, delays and timing in reported cases, and consistent testing policies (Dowd et al., 2020; Goldstein and Lee, 2020; Dudel et al., 2020; Harman et al., 2021).

Our results suggest that it is thus crucial to maintain testing efforts to detect cases both among vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, even if those infections do not evolve into severe cases or death (The Rockefeller University, 2021; Mina and Andersen, 2021; Lipsitch et al., 2021). Failing to keep track of all cases properly, irrespective of vaccination status, leads to the same scenario of the beginning of the pandemic, in which governments and researchers were only able to detect a part of the infections, missing key information from the asymptomatic transmission, as testing was restricted to severe and hospitalized cases (Li, 2020; Nishiura, 2020; Wu et al., 2020). This, in turn, leads to imprecise knowledge of the current spread of the virus among the vaccinated and the unvaccinated population, which consequently leads to distorted estimates of vaccine effectiveness at the population level. This also prevents us from accurately identifying the sociodemographic factors associated with breakthrough infections and their long-term consequences on health.

Background

It has been widely acknowledged that the CFR is an indicator that is sensitive to demographic factors, delays in reported cases, and testing policies. (Dowd et al., 2020; Rajgor et al., 2020; Goldstein and Lee, 2020; Green et al., 2020; Harman et al., 2021; Smith, 2021; Luo et al., 2021; Undurraga et al., 2021). The CFR is defined as the ratio between the number of confirmed deaths from a disease and the number of reported cases in a given time. Hence, any factor that impacts these numbers will affect the CFR (Rajgor et al., 2020; Green et al., 2020). Of particular importance is the ability to detect cases through testing. Because testing availability may be limited and testing strategies may change over time, not every case is reported. This leads to an artificially high CFR, overestimating the risk of death. In contrast, vital registration systems may experience delays in reporting deaths or face underreporting issues. In that case, the CFR can be artificially low, underestimating the risk. Hence, because these variations in the CFR may not reflect the true mortality risk, its interpretation requires caution and awareness.

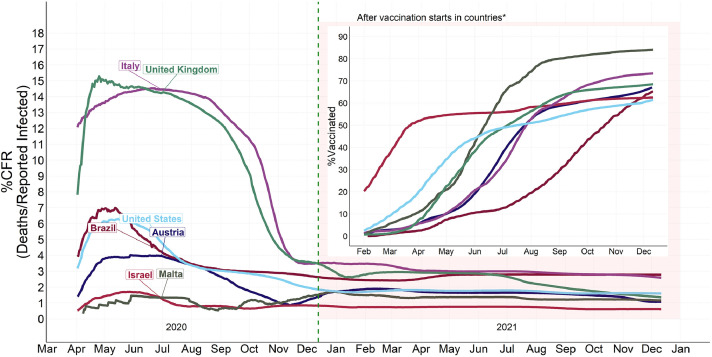

In the presence of vaccines, there is an added complexity to the CFR, as it will also depend on the detection of infections among vaccinated individuals and on the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing deaths. With increased testing capacity, vaccination is supposed to lead to a decline in the CFR because vaccinated individuals may still get infected but develop less severe symptoms than nonvaccinated individuals (Hall et al., 2021). Nonetheless, that is not what happens necessarily in the observed CFR, at least not for several months after vaccination uptake, as shown in Figure 1 . Israel was the first country to have strong vaccine uptake, with the country fully vaccinating half of its total population in just two months after the rollout began (December 19, 2021). This trend was overturned by Malta, that despite a slower pace at the beginning of the vaccination rollout (January 24, 2021), they had already 80% of its total population fully vaccinated by August 2021. The United States started a few days before Israel but had a slower initial reaction and reached higher vaccination levels only by the end of 2021 (∼60%). Austria increased its vaccination pace starting June 2021 and by September of the same year had slightly more than 60% of its population fully vaccinated. For most of the countries selected, the trajectories of the percentage vaccinated follow a similar S-shaped curve, with a sharper increase at the beginning followed by some months of stability. Brazil is an exception with a slower initial uptake that lasted almost 6 months, followed by an almost linear increase from August 2021 to December 2021. However, despite the country-specific differences in the timing and pace of vaccination, the respective CFRs remained relatively stable through most of the observed time period (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The left part of the graph refers to 2020, before vaccination, and shows the % case fatality rate (CFR) in selected countries (from April 2020 to mid-Dec 2021). The right part of the graph includes the percentage of fully vaccinated persons (%), with the * dashed line starting with the first vaccine uptake country (United States, December 13, 2020, followed, in order, by Israel = December. 19, 2020; United Kingdom = December. 20, 2020, Austria = December. 27, 2020; Italy = December. 27, 2020; Brazil = January 16, 2021; Malta = January 24, 2021). We end in mid-December, considering most cases before the Omicron variant becomes the most cases. Before February 2021, most countries had not started to mass vaccinate and were amidst the 2020 winter lockdowns; therefore, we considered the vaccination trajectory after February 2021. Source: Our World in Data (Mathieu et al., 2021).

This may lead to questioning whether vaccines are not being effective in reducing deaths in most of these countries. For instance, can one conclude that declines in the CFR observed in the United Kingdom after July 2021 imply that vaccines are more effective in preventing deaths there, whereas, in Malta,Israel and Austria, they are not? To shed light on what is driving those patterns, we look into how the CFR behaves in the presence of vaccines for a specific age group.

Methods

In the presence of vaccines, additional factors affect the CFR because we have a mixed population of vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Considering a population that is not yet 100% vaccinated, which is the case for most global populations currently, we can define the total CFR as the weighted sum of the CFR of the unvaccinated () and the CFR of the vaccinated ():

| (1) |

where the weight is the ratio between the total number of vaccine breakthroughs and the total number of ever infected and detected cases (see Supplementary Material for a full derivation of ). Previous studies showed that the CFR of the unvaccinated can be expressed as the ratio of the fatality rate at age among the unvaccinated () to the probability of detecting persons ever infected until time at age among the unvaccinated () (Sánchez-Romero et al., 2021). The CFR of the vaccinated can be expressed in the same manner, with the difference that the fatality rate pertains to deaths among the vaccinated, whereas the detected refers to infections among the vaccinated. If we consider that the probability of dying for the vaccinated is times lower than for the unvaccinated, we can express the fatality rate of the vaccinated as . Hence, the CFR in the presence of vaccines is:

| (2) |

with , being the ratio of the probability of detecting cases among vaccinated to detecting cases among unvaccinated. This result shows that the CFR depends not only on how effective vaccines are in preventing deaths () (refer to the Supplementary Material for an extension on the vaccine effectiveness definition considering prevention of transmission) but also on the probability of detecting both infected persons among the vaccinated - breakthrough infections -, and infected persons among the unvaccinated . This relationship indicates that the lower (respectively higher) the effectiveness of vaccination preventing deaths (i.e. a higher value of ), the more (respectively less) we have to detect among the vaccinated (i.e. a higher value of ), to keep the CFR constant. In other words, a scenario of constant CFR can indicate a low (respectively highly) effective vaccine with high (respectively. limited) detection among the vaccinated compared with the unvaccinated. Ideally, the best scenario is a high vaccine effectiveness coupled with high detection rate among vaccinated individuals.

To illustrate the sensitivity of the CFR to the interaction between vaccine effectiveness in preventing deaths and the efforts in detecting infections among both the vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, we simulate three hypothetical CFR scenarios that result from a different combination of and values. To better illustrate the sensitivity of the CFR, we will focus on the oldest age group that has the highest risk of death and was the first group to be vaccinated. We avoid the potential bias produced by the different vaccination strategies by age by using the oldest age group. Because age-specific data on deaths, vaccination rates, and testing are not standardized across countries, we will illustrate with the case of Austria, for which we have detailed data on deaths, infections, vaccination status, and testing by age (See data on Supplementary Material for more details). In addition, not only is Austria the second country in the world with the highest level of testing as of August 15, 2020 (Hasell et al., 2020) but it also has mandatory molecular reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction testing for in-person services, entering bars and restaurants, as well as engaging in some indoor activities like gyms and public pools. The observed CFR is calculated using data from the Federal Ministry for Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection (BMSGPK), Austrian COVID-19 Open Data Information Portal (2021) BMSGPK, Österreichisches COVID-19 Open Data Informationsportal (2021), whereas the simulated CFR values are calculated using data from Richter et al., 2020a, b. Following Hall et al., 2021, the value of vaccine effectiveness in reducing deaths for ages above 84 is set at 0.85. The initial simulated CFR value is assumed to equal the average CFR value observed between February 2021 and November 2021. For details on the simulation and key relationships between vaccine effectiveness, detection rates, and the CFR, we refer the reader to the Supplementary Material. Total CFR for selected countries and their percentage of fully vaccinated persons are from Our World in Data (Mathieu et al., 2021). In addition, all data, codes, and methods used in this study are provided by the authors in https://osf.io/uvwdj/?view_only=517e735ca10848adacd73b93a40eb9c0.

Results

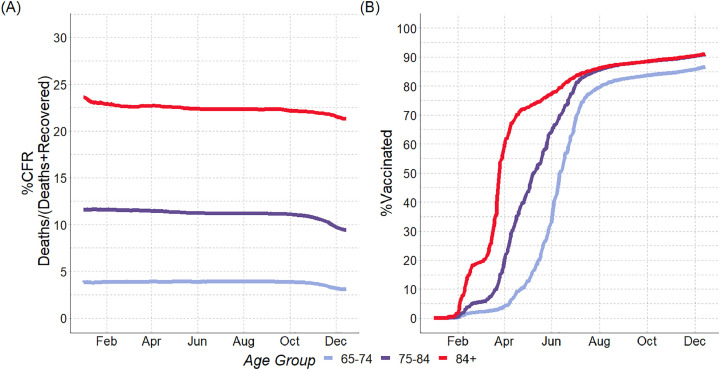

We will illustrate with the case of Austria, focusing on the oldest age group (aged 84+ years) that has the highest risk of death and was the first to be vaccinated. By the end of December 2021, a little over 90% of persons aged >84 were fully vaccinated, as shown in panel (B), in Figure 2 . Nonetheless, similar to several countries depicted in Figure 1, the CFR for the group aged 84+ years in Austria also remained stable across time (Figure 2., panel A). If the detection rate of the unvaccinated does not change over time, the observed constant CFR occurs because the effort in detecting the infected among the vaccinated relative to the unvaccinated is equal to effectiveness of vaccination in preventing deaths.

Figure 2.

Panel (A) % Case Fatality Rate (CFR); Panel (B) Percentage of fully vaccinated persons (%). Austria, by age, from January 2021 to December 2021. Source: The number of people vaccinated in each group is taken from Federal Ministry for Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection (BMSGPK), Austrian COVID-19 Open Data Information Portal (2021).

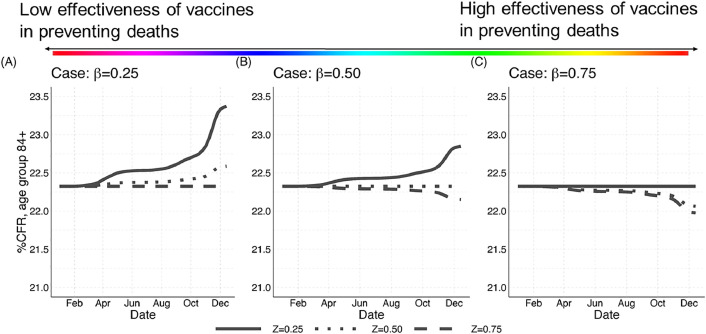

To illustrate this point, we simulate three hypothetical CFR scenarios that result from a different combination of vaccine effectiveness in reducing deaths, which we call , and the detection rate of infections among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated persons, which we call – or to what extent are governments willing to detect both breakthrough infections and infections among unvaccinated persons (for a full derivation of the CFR in the presence of vaccines and the parameters used for the simulation we refer the reader to the Supplementary Material). First, Figure 3 presents how different combinations of and values can yield constant CFRs, going from the lowest value of vaccine effectiveness to the highest (Panels A to C, respectively). The black lines are estimated CFR trajectories conditional on and values. Notably, Figure 3 is a zoomed-in version of panel A in Figure 2. Although the % CFR in panel A in Figure 2 ranges from 0% to 23%, in Figure 3, it varies between 21% and 23%. Panel A shows that the CFR remains constant when detecting breakthrough infections relative to nonvaccinated individuals is high (), despite low vaccine effectiveness. Conversely, when the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing deaths is high, and thus a decline in the CFR should necessarily be observed, the CFR can remain constant when the ability to detect infections among the vaccinated is low (Panel C, for ). Second, when the efforts of detecting the infected among the vaccinated, relative to the unvaccinated (), is lower than the ability of vaccines in preventing deaths , the CFR will increase.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the % Case Fatality Rate (CFR) for the age group 84+ in Austria (January 2921 to Dec 2021) by three different parameter values of and . Source: Simulated CFR values are calculated using data from (Richter et al., 2020b, a) and BMSGPK, COVID-19 Open Data Informationsportal (2021). Note: The initial value of the simulated CFR is assumed to be equal to the average CFR value observed between February 2021 and November 2021. For more details, refer to the Supplementary Material.

This latter scenario may happen, for instance, in a context where governments only track breakthrough infections among those who present severe symptoms (which leads to a high CFR among the vaccinated). Does that mean that vaccines are not effective in reducing deaths among Austrians aged 84+ years? Not necessarily, because the CFR also depends on testing policies and the capacity of countries in detecting both breakthrough infections and infections among unvaccinated individuals. This shows that unless efforts are directed at detecting infections among vaccinated (i.e., all breakthrough cases) and unvaccinated individuals, it is hard to disentangle the effect of vaccines in reducing deaths from the probability of detecting infections on the CFR.

Discussion

The CFR is an indicator that is sensitive to demographic factors, case reporting and testing strategies, which have been widely acknowledged in the literature. This has led specialists to argue that the CFR needs to be interpreted with caution, as it may not accurately reflect the true mortality risk. Our contribution to this debate is to additionally demonstratehow the CFR behaves in the presence of vaccines. We show that the CFR also depends on whether breakthrough cases are accurately detected. Thus, in the absence of information on infections among both the vaccinated and the unvaccinated, the CFR may be misleading, especially when used to assess the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing deaths or the spread of the virus. A declining CFR like that observed in the United Kingdom starting July 2021 could either indicate that the virus is reducing the mortality rate or that young unvaccinated individuals are infected at higher rates than vaccinated older age groups. With no knowledge of the positivity rate among the vaccinated and unvaccinated, it becomes very difficult to disentangle those factors. We observe, for most countries, that despite a high proportion of vaccinated individuals, the CFR does not significantly decline for almost a year after vaccine uptake. That was even more remarkable for cases like Austria, which has an exceptional and consistent testing strategy throughout time. This reinforces that widespread testing is still a key policy strategy to detect asymptomatic or mild infections among both the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations (The Rockefeller University, 2021). Efforts to properly detect those cases are important for assessing immunity duration (Seow et al., 2020) and if extra booster shots will be needed, especially with new, more contagious variants spreading quickly throughout the world and more breakthrough infections recorded (Kupferschmidt, 2021; Barda et al., 2021; Arbel et al., 2021; Andrews et al., 2022; Watson, 2022). This may be a decisive factor in informing governments on the different set of strategies they may need to employ throughout the pandemic, including a mixture of vaccines and nonpharmaceutical measures (Dagan et al., 2021), as immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection may progressively wane with time (Haghpanah et al., 2021; Reynolds, 2021; Stamatatos, 2021). In addition, the availability or logistics of subsequent phases of mass vaccination may not take place as fast as needed or for all age groups simultaneously.

Furthermore, although most people who develop COVID-19 and survive can recover within weeks or a few months, depending on the level of disease severity, some individuals suffer from chronic damage to their lungs, heart, kidneys, or brain, whereas others will develop long COVID – a different subset of chronic illnesses and extreme lingering effect (Carfì et al., 2020; NIH, 2021; Vaes et al., 2021). If we do not keep track of the characteristics of vaccinated individuals who have mild breakthrough infections, we not only hamper a proper estimation of vaccine failure rates based on age, gender, ethnicity, medication use, or immune function but also miss important information on factors that aggravate long COVID symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank José Euclides da Silva Goncalves and Vitor Sommavilla de Souza Barros for their insightful comments and constructive feedback.

Ethical Approval statement

This study did not perform an analysis of human subjects and/or animals. All data used are publicly available and noted in the main text and supplementary materials. In addition, the authors provide the codes and data to replicate the study at https://osf.io/uvwdj/?view_only=517e735ca10848adacd73b93a40eb9c0.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.03.059.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 booster vaccines against covid-19 related symptoms, hospitalisation and death in England. Nature Medicine. 2022 doi: 10.1038/S41591-022-01699-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbel R, Hammerman A, Sergienko R, et al. BNT162b2 Vaccine Booster and Mortality Due to Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;385:2413–2420. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2115624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. The Lancet. 2021;398:2093–2100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02249-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton A. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Among Residents of Two Skilled Nursing Facilities Experiencing COVID-19 Outbreaks — Connecticut, December 2020–February 2021. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70:396–401. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM7011E3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020;324:603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) COVID-19 Breakthrough Case Investigations and Reporting. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/health-departments/breakthrough-cases.html. Accessed 8 Jun 2021.

- Cyranoski D. Alarming COVID variants show vital role of genomic surveillance. Nature. 2021;589:337–338. doi: 10.1038/D41586-021-00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384:1412–1423. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd JB, Andriano L, Brazel DM, et al. Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117:9696–9698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004911117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudel C, Riffe T, Acosta E, et al. Monitoring trends and differences in COVID-19 case-fatality rates using decomposition methods: Contributions of age structure and age-specific fatality. PLOS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry for Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection (BMSGPK), (2021) Österreichisches COVID-19 Open Data Informationsportal. https://www.data.gv.at/covid-19/. Accessed 7 Sep 2021.

- Goldstein JR, Lee RD. Demographic perspectives on the mortality of COVID-19 and other epidemics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117:22035–22041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006392117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MS, Peer V, Schwartz N, Nitzan D. The confounded crude case-fatality rates (CFR) for COVID-19 hide more than they reveal—a comparison of age-specific and age-adjusted CFRs between seven countries. PLOS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacisuleyman E, Hale C, Saito Y, et al. Vaccine Breakthrough Infections with SARS-CoV-2 Variants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384:2212–2218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2105000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghpanah F, Lin G, Levin SA, Klein E. Analysis of the potential impact of durability, timing, and transmission blocking of COVID-19 vaccine on morbidity and mortality. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35 doi: 10.1016/J.ECLINM.2021.100863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Saei A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine coverage in health-care workers in England and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection (SIREN): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. The Lancet. 2021;397:1725–1735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00790-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman K, Allen H, Kall M, Dabrera G. Interpretation of COVID-19 case fatality risk measures in England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75:415–416. doi: 10.1136/JECH-2020-216140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasell J, Mathieu E, Beltekian D, et al. A cross-country database of COVID-19 testing. Scientific Data. 2020;7 doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-00688-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keehner J, Horton LE, Pfeffer MA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection after Vaccination in Health Care Workers in California. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384:1774–1775. doi: 10.1056/nejmc2101927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt K. New mutations raise specter of ‘immune escape’: SARS-CoV-2 variants found in Brazil and South Africa may evade human antibodies. Science (80-) 2021;371:329–330. doi: 10.1126/science.371.6527.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, et al. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. The Lancet. 2021;397:61–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) Science. 2020;368:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M, Krammer F, Regev-Yochay G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals: measurement, causes and impact. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2021;22(1):57–65. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00662-4. 202122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G, Zhang X, Zheng H, He D. Infection fatality ratio and case fatality ratio of covid-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature Human Behaviour. 2021 doi: 10.1038/S41562-021-01122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina MJ, Andersen KG. COVID-19 testing: One size does not fit all. Science. 2021;371:126–127. doi: 10.1126/SCIENCE.ABE9187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (2021) NIH launches new initiative to study “Long COVID” | National Institutes of Health (NIH). https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/nih-launches-new-initiative-study-long-covid. Accessed 7 Jun 2021.

- Nishiura H. Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19) Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:154–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NNDSS (2021) NNDSS | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Rajgor DD, Lee MH, Archuleta S, et al. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20:776–777. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CJ. Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection rescues B and T cell responses to variants after first vaccine dose. Science. 2021;372:1418–1423. doi: 10.1126/science.abh1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Schmid D, Chakeri A, et al (2020a) Epidemiologische Parameter des COVID19 Ausbruchs-Update.

- Richter L, Schmid D, Stadlober E. Methodenbeschreibung für die Schätzung von epidemiologischen Parametern des COVID19 Ausbruchs. Österreich Einleitung. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Romero M, di Lego V, Prskawetz A, Queiroz BL. An indirect method to monitor the fraction of people ever infected with COVID-19: An application to the United States. PLoS ONE. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow J, Graham C, Merrick B, et al. Longitudinal evaluation and decline of antibody responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature Microbiology. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.09.20148429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MP. Role of Ascertainment Bias in Determining Case Fatality Rate of COVID-19. Journal of epidemiology and global health. 2021;11:143–145. doi: 10.2991/JEGH.K.210401.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatatos L. mRNA vaccination boosts cross-variant neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science. 2021;372:1413–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.abg9175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Rockefeller University . 2021. Study of “breakthrough” cases suggests COVID testing may be here to stay.https://www.rockefeller.edu/news/30404-covid-variant-infection-after-vaccination/ Accessed 28 Jul 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga EA, Chowell G, Mizumoto K. COVID-19 case fatality risk by age and gender in a high testing setting in Latin America: Chile, March–August 2020. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2021;10 doi: 10.1186/S40249-020-00785-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaes AW, Goërtz YMJ, Van Herck M, et al. Recovery from COVID-19: a sprint or marathon? 6-month follow-up data from online long COVID-19 support group members. ERJ open research. 2021;7:00141–02021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00141-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson C. Three, four or more: what's the magic number for booster shots? Nature. 2022;602:17–18. doi: 10.1038/D41586-022-00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SL, Mertens AN, Crider YS, et al. Substantial underestimation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the United States. Nature Communications. 2020;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18272-4. 202011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.