Abstract

Background:

Epigenetic changes associated with HPV-driven tumors have been described; however, HPV type-specific alterations are less well understood. We sought to compare HPV16-specific methylation changes to those in virus-unassociated head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC).

Methods:

Within The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), 59 HPV16+ HNSCC, 238 non-viral HNSCC (no detectable HPV or other viruses), and 50 normal head and neck tissues were evaluated. Significant differentially methylated regions (DMR) were selected, and key associated genes identified. Partial Least Squares (PLS) models were generated to predict HPV16 status in additional independent samples.

Results:

HPV infection in HNSCC is associated with type-specific methylomic profiles. Multiple significant DMRs were identified between HPV16+, non-viral and normal samples. The most significant differentially methylated genes, SYCP2, MSX2, HLTF, PITX2 and GRAMD4, demonstrated HPV16-associated methylation patterns with corresponding alterations in gene expression. Phylogenetically related HPV types (alpha-9 species; HPV31, HPV33 and HPV35) demonstrated a similar methylation profile to that of HPV16 but differed from those seen in other types such as HPV18 and 45 (alpha-7).

Conclusions:

HNSCC linked to HPV16 and types from the same alpha species are associated with a distinct methylation profile. This HPV16-associated methylation pattern is also detected in cervical cancer and testicular germ cell tumors. We present insights into both shared and unique methylation alterations associated with HPV16+ tumors and may have implications for understanding the clinical behavior of HPV-associated HNSCC.

Impact:

HPV type-specific methylomic changes may contribute to understanding biologic mechanisms underlying differences in clinical behavior among different HPV+ and HPV− HNSCC.

Keywords: HPV, Methylation

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck cancer is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and accounts for 1-2% of cancer-related deaths (1). Over 90% of head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) and typically arise from the oral cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx. The etiology of HNSCC include tobacco exposure, alcohol consumption and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The incidence of HPV-associated HNSCC has significantly increased over the last 2 decades (2). In addition to HNSCC, high-risk HPV infection, predominately HPV16 and HPV18, has been causally associated with many different cancer types including those of the cervix, penis, anus, vulva, and vagina. HPV16 is the most commonly implicated HPV type in HNSCC (3) and frequently involves the oropharynx (3,4). Of clinical relevance, HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers (OPSCC) expressing wild type p53 and high levels of p16, have better prognosis and response to chemoradiation (2,5,6).

The pathophysiology of HPV-associated HNSCC involves integration of HPV virus into the host genome, upregulation of oncoproteins E6 and E7 (7), and degradation of tumor suppressors p53 and Rb respectively (8). Additional molecular alterations occur at the epigenetic level and include DNA histone modification, chromatin remodeling, modulation of non-coding RNAs and, most notably, aberrant DNA methylation. It has been postulated that these methylation changes may have important contributions to neoplastic progression, treatment response phenotypes and prognosis (5,9). Several studies have demonstrated that HPV+ HNSCCs and cervical cancers have significant overexpression of DNA methyltransferases and higher levels of CpG island hypermethylation (9–11). Indeed, HPV-positive OPSCCs have been shown to express distinct gene methylation profiles as compared to HPV-negative OPSCCs (6,12).

HPV-associated HNSCC (and in particular, oropharyngeal SCC) demonstrates distinct clinical behavior and prognosis, with improved survival and lower risk of recurrence, as compared to their HPV-negative counterparts. (13) Indeed, as a whole, HPV+ HNSCC demonstrate increased response to radiation-based therapy and consequently, there has been substantial interest in treatment de-escalation strategies to optimize the therapeutic ratio for patients affected with this disease. (14) Nonetheless, it is notable that ~20% of HPV-positive HNSCC have poor treatment response and prognosis, and the biologic basis for this disparate behavior remains to be fully elucidated. (15) Beyond treatment, it is important to note that despite the predicted continued increase in incidence particularly of HPV+ HNSCC, there are no established or standardized screening methods for this disease. (16)

Identifying the spectrum of epigenetic changes across the genome may provide clues as to the molecular mechanisms that drive the degree of treatment response and in turn, prognosis. Critical methylation events may contribute to the differences seen between strong and poor treatment responders in both HPV+ and HPV− HNSCC patients. This line of investigation may yield actionable targets or pathways that could be manipulated to enhance treatment response and prognosis. Furthermore, the ability to detect DNA methylation events in patient saliva or plasma may allow the leveraging of epigenetic biomarkers for the purposes of screening, early diagnosis, and surveillance.

Although several studies have examined the genome-wide methylation differences between HPV+ and HPV− HNSCC (17–24), comprehensive analyses that include comparisons to normal head and neck tissues, which allow insight into carcinogenesis-associated epigenetic changes, are lacking. Moreover, the HPV type-specific impact on methylation patterns has not been fully evaluated. The objective of this study is to leverage genome-wide methylation array data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to characterize differential methylation alterations associated with both HPV16+, other non-HPV16 HPV+ and completely non-viral HNSCC in comparison to normal head and neck tissues.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

HPV definition and virus status

Read counts available in the supplementary material from Cao et al (25) and Tang et al (26) were downloaded and merged. TCGA samples with more than 100 reads from a specific virus type were considered positive for that virus type. Samples with no reads from any virus type were labeled as non-viral tumor samples while tumor samples with 1-100 reads were categorized as ‘low counts’ and not used in our analysis.

TCGA Methylation Dataset

The raw Illumina450 IDAT files selected for HNSCCs were downloaded from TCGA and normalized using Control Probes with background correction as implemented in the minfi bioconductor package. Significant differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were selected using the following criteria: FDR corrected p-value < 0.01, mean beta difference > 0.3 for HPV16 vs. Non-viral tumors. The mean beta difference threshold was increased to 0.4 for the Normal vs. HPV16 and Normal vs. Non-viral comparisons, to account for the expected larger number of differences when comparing normal vs. tumor tissue (27). In addition, probes with no significant neighbors, defined as being within 500 base-pairs (28), were not considered to be significant.

TCGA RNA and DNA Copy Number data

All TCGA data were downloaded and processed as we have previous described (29). In short, the normalized and debatched RNAseq data file (EBPlusPlusAdjustPANCAN_IlluminaHiSeq_RNASeqV2.geneExp.tsv) were downloaded from Genomic Data Commons (GDC), https://gdc.cancer.gov/about-data/publications/pancanatlas . Samples listed in the Merged Sample Quality Annotation were removed due to potential quality issues. The expression values were log2 transformed using log2(x+1). For characterization of the tumor immune microenvironment, we used the same genes as previously reported (30).

The PanCancer Atlas DNA copy number data (GISTIC data) were extracted from the Copy Number file (broad.mit.edu_PANCAN_Genome_Wide_SNP_6_whitelisted.seg http://api.gdc.cancer.gov/data/00a32f7a-c85f-4f86-850d-be53973cbc4d). Samples listed in the Merged Sample Quality Annotations spreadsheet (merged_sample_quality_annotations.tsv) were excluded from further analysis. Based on GISTIC2.0 (31) DNA copy number analysis, the following numeric values were assigned with the cBioPortal interpretation presented in parentheses: −2 = Deep Deletion (possibly a homozygous deletion); −1 = Shallow Deletion (possible heterozygous deletion); 0 = Diploid; +1 = Gain (a few additional copies, often broad); +2 = Amplification (more copies, often focal).

Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) Methylation Data

The raw Illumina450 IDAT files were downloaded from GEO (GSE68379) (32) and processed in the same fashion as the TCGA data. Cell lines with missing TCGA “Tumor Type” were removed from the analyses.

GSE38266 HPV+ and HPV− HNSCC Public Dataset

The GSE38266 (33–35) dataset was downloaded from GEO and the processed data were used for validation analyses.

PCA Model

For PCA modeling, tumor samples with known viral type (n=320) and normal samples (n=50) were included. Of note, CpG probes with more than 20% missing values were removed. Each column was centered but not scaled before the PCA model was calculated.

Derivation of PLS-DA models

The initial objective was for the selection of specific probes that were uniquely altered when comparing non-viral tumors to HPV16 tumors but not when comparing normal tissue to all tumor tissues. The converse goal was then to identify probes that differed in methylation between normal and all tumor tissues but were not altered in association with viral status. The following criteria were used to select the optimal probes for the Partial Least Squares (PLS) model: Probes with greater than 20% missing values were removed. OF note, the TCGA methylation data were generated using the no longer available Illumina 450K array. To ensure future comparability of our results to the newer Illumina EPIC Chip, we removed probes that are not on this latter platform. HPV16-specific probes: For the HPV16+ PLS model, any probe that was differentially methylated in normal vs. tumor with Δ β-value>0.1 or p<0.05 was removed, thus ensuring that only HPV16+-specific probes were selected. Subsequently, each probe was ranked using the geometric mean of the Δ β-value and the −log10(p-value) for HPV16+ vs non-viral tumors. The top 100 significant probes (p<0.0001 and Δ β-value>0.2) with increased methylation in HPV16+ tumors compared to non-viral tumors and the top 100 probes with decreased methylation in HPV16+ tumors compared to non-viral tumors were selected for the HPV16+ PLS model. Tumor- vs. normal-specific probes: For the tumor vs. normal model, probes that were differentially methylated in HPV16 vs. non-viral tumors with Δ β-value>0.1 or p<0.05 were removed, thus ensuring that only tumor vs. normal-specific probes were selected. Following this selection, each probe was ranked using the geometric mean of the Δ β-value and the −log10(p-value) for tumor vs. normal. The top 100 significant probes (p<0.0001 and Δ β-value>0.2) with increased methylation in tumor compared to normal samples and the top 100 probes with decreased methylation in tumors compared to normal samples were selected for the final PLS model. A binary response variable was used with the designation of “1” for HPV16+ tumors and “0” for non-viral tumors in the HPV16 PLS model, while “1” was used for tumors and “0” for normal in the Tumor vs. Normal PLS model. Samples with a predicted value above 0.5 for the HPV16 PLS model were considered to be HPV16-related and those less than or equal to 0.5 considered to be HPV16-unrelated. Cross-validation was used to estimate the optimal number of PLS components.

Data Analyses

All data analyses and figures were performed/generated using MATLAB R2020a (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States).

RESULTS

HPV status of TCGA HNSCC samples

Using the criteria defined in the Methods section, we identified 59 HPV16+ tumors, 238 non-viral tumors, and 50 normal samples with available methylation data from the TCGA PANCAN HNSCC cohort, listed in Supplementary Table S1. Other virus types detected included: HPV33 n=8, HHV5 n=6, HPV35 n=3, HHV1 n=1, CYMV n=1, HBV n=1, HHV4 n=1 and HPV56 n=1. There were an additional 171 samples with low counts (<100) and 31 with missing information. All eligible head and neck cancers were included in this study. Of this group, a total of 56 of 297 cases could be distinguished as most likely oropharyngeal by TCGA-defined anatomical sites (e.g., base of tongue, tonsil, oropharynx; Supplementary Table S1).

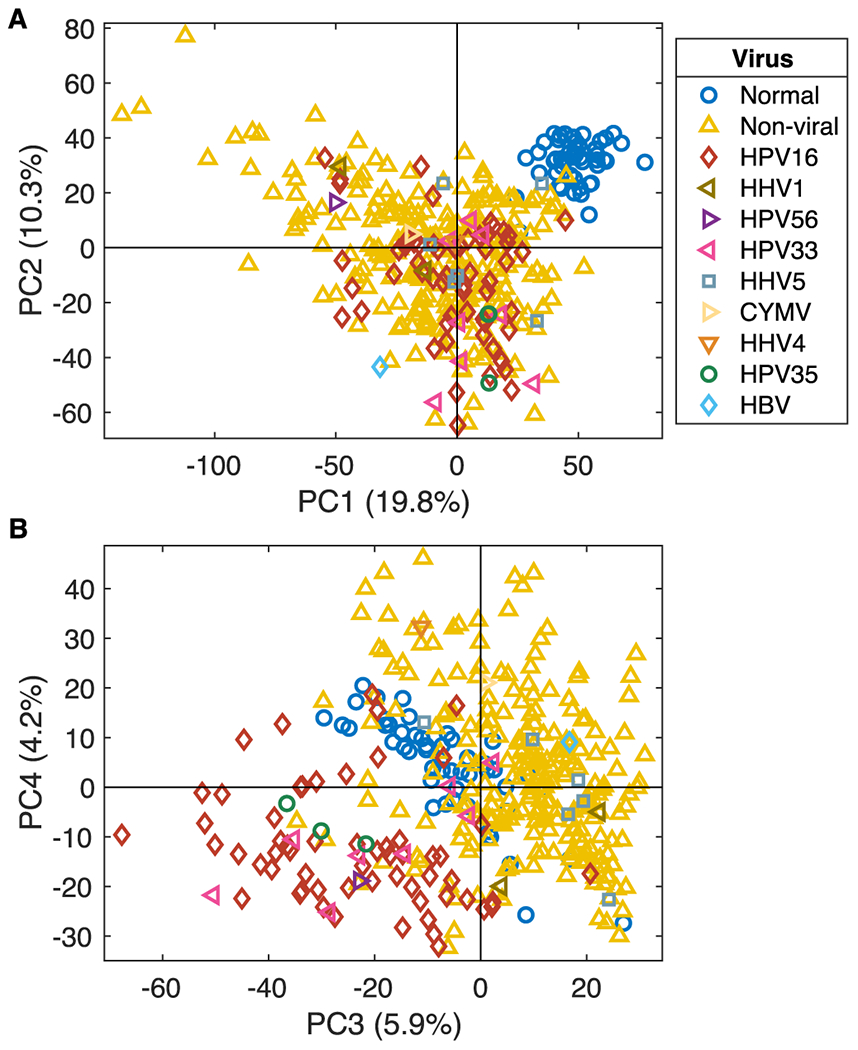

Unbiased Analysis of H&N Methylation Data

A principal component analysis (PCA) model using Illumina 450 methylation array data from all 370 samples with known viral status and all probes with less than 20% missing values (n= 484,933) was performed. The score plot for the first two PCA components (PC1 and PC2), explaining 19.8% and 10.3% of the variation respectively (Figure 1A), revealed a clear separation of the normal samples (blue circles) from all tumor samples. This separation is seen in both PC1 and PC2; suggesting that the largest contribution of change in methylation levels arise from tumor vs. normal differences. A plot of the third and fourth PCA components (Figure 1B), accounting for 5.9% and 4.2% of the variation, demonstrated a separation of the HPV16+ tumor samples (red diamonds). HPV33+ (pink left triangles) and HPV35+ tumor (green circles) samples are noted to overlap with HPV16+ tumors, suggesting that these types all share a similar methylation pattern. That virus type segregations occur in the third and fourth PCA components, indicates that there are major differences in methylation patterns between tumor-associated HPV types.

Figure 1. PCA of Methylation Data.

A PCA model using 572 samples and 484, 933 CpG probes was calculated. The first two PCA components, (A) show that normal samples (blue circles) separate from tumor samples, independent of virus status. PCA components three and four (B) display separation of HPV16+ (red diamonds) from non-viral and normal samples. HPV35+ (green circles), HPV33+ (pink left-triangles), and HPV56+ (purple right-triangle) samples cluster together with HPV16+ samples.

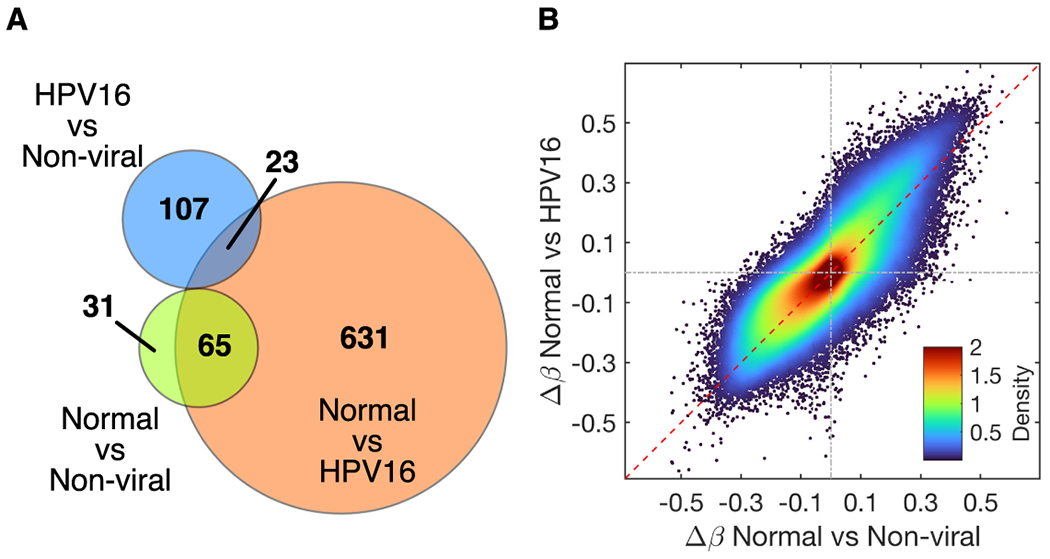

Differential Methylated Regions in HPV16+ vs. non-viral tumors

Using our DMR selection criteria, we identified 130 significant probes (mapping to 57 genes) being differentially methylated between HPV16+ and non-viral tumors. Similar comparisons between normal tissue and non-viral tumors generated 96 significant probes while normal samples versus HPV16+ tumors yielded 719 significant probes. (Figure 2A, probes listed in Supplementary Table S2 A–C). The density scatter plot, Figure 2B, demonstrates a linear relationship between Δ β-value for normal tissue samples vs. HPV16+ tumors and normal tissue samples versus non-viral tumors. There is a clear vertical shift in the upper right quadrant indicating that there is a greater increase in the degree of methylation for HPV16+ tumors as compared to non-viral tumors.

Figure 2. Differentially Methylated DMR’s.

The overlaps between the different comparison groups are depicted in a Venn diagram (A). The Δ β-values for normal vs. HPV16+ tumors and normal vs. non-viral tumors demonstrate a linear relationship (B).

Gene Specific Differential Methylation in HNSCC

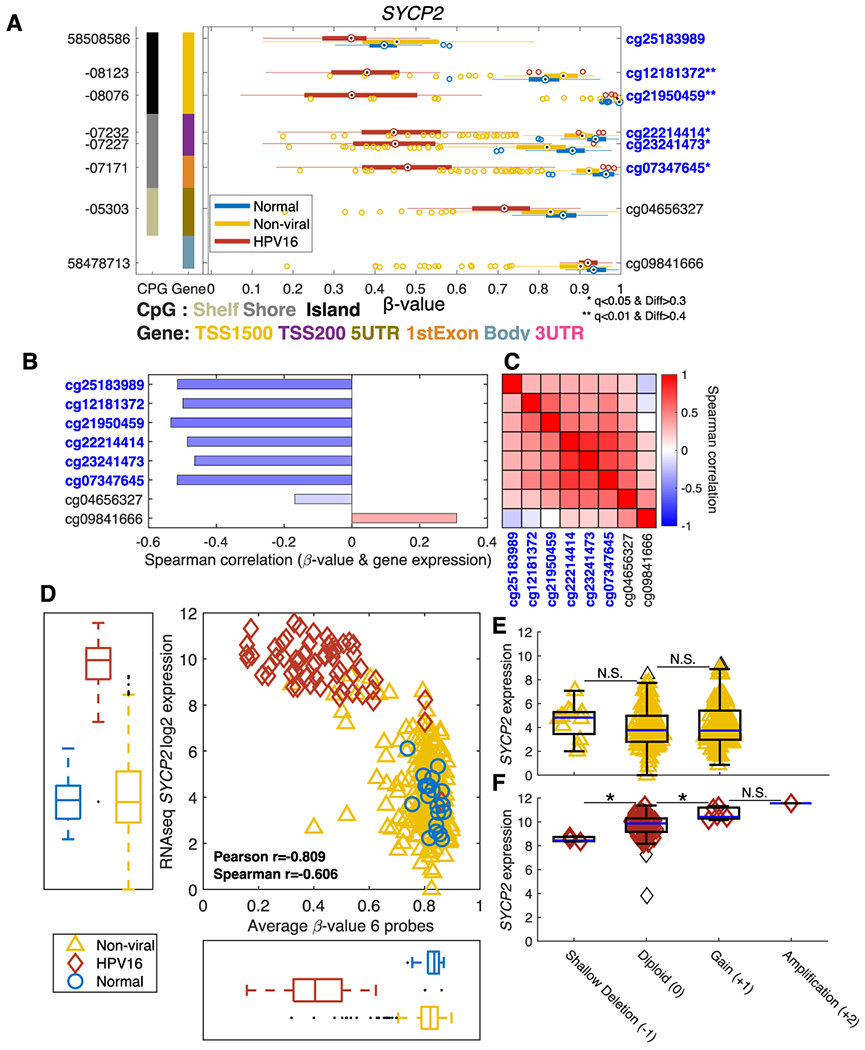

SYCP2

Synaptonemal complex protein 2 (SYCP2, 20q) was among the most significant and representative of genes identified in this analysis that are hypomethylated in HPV16+ as compared to both non-viral tumors and normal samples. Figure 3A clearly demonstrates that HPV16+ samples (red) show a lower degree of methylation in SYCP2 compared to non-viral tumors (yellow) and normal samples (blue). Five of the 8 CpG-probes are significantly differentially methylated and are all located in the TSS1500-1st Exon region and may thus potentially impact the transcription of SYCP2. Each probe’s correlation to corresponding RNAseq gene expression levels is shown in Figure 3B which demonstrates a strong negative correlation (r<−0.4) for six of these probes. Methylation levels are also correlated between these six probes, as shown in the correlation heatmap, Figure 3C. The negative correlation between the average methylation level of SYCP2 and gene expression was very high suggesting that expression of SYCP2 is regulated by methylation (Figure 3D). There is a clear separation of the HPV16+ samples in both the methylation and gene expression spaces. By copy number analysis for SYCP2, non-viral tumors demonstrate some variations falling into Shallow Deletion, Diploid and Gain categories, but they do not seem to be related to overall expression levels (Figure 3E). HPV16+ tumors samples show a progressive trend in association with SYCP2 expression from Shallow Deletions to Amplifications (Figure 3F). These results indicate that the high expression of SYCP2 in HPV16 tumors is very likely to be epigenetically regulated by methylation and not by copy number alteration events. Notably, out of 515 available HSNCC samples from the TCGA PanCancer Atlas HNSC dataset in cBioportal, SYCP2 was found to harbor very few mutations in HNSCC, with only 3 samples showing a truncating mutation and 4 samples harboring a missense mutation, all of unknown significance(36).

Figure 3. Methylation Profile of SYCP2.

The methylation levels for the 8 probes of SYCP2 across all samples are depicted in boxplots with normal tissue (blue), non-viral tumors (yellow) and HPV16+ tumors (red) (A). The β-values are shown on the x-axis where values of “0” and “1” indicate no and 100% methylation, respectively. The genomic positions and the probe-ids are shown on the left and right y-axes, respectively. The left most column represents the type of CpG region while the second column indicates the regional location of the probe within the gene. Significantly differentially methylated probes selected for average SYCP2 methylation are marked in blue * q<0.05 and Δβ>0.3 ** q<0.01 and Δβ>0.4. The correlation between the methylation level for each probe and SYCP2 mRNA expression is demonstrated (B). The pairwise Pearson correlation between the probes for SYCP2 is depicted in a heatmap (C). The average methylation of the six probes with high individual correlation is compared to SYCP2 mRNA expression across all TCGA samples (D). The copy number dependent expression of SYCP2 is shown for non-viral tumor samples in (E) and for HPV16+ tumors in (F). * p<0.05.

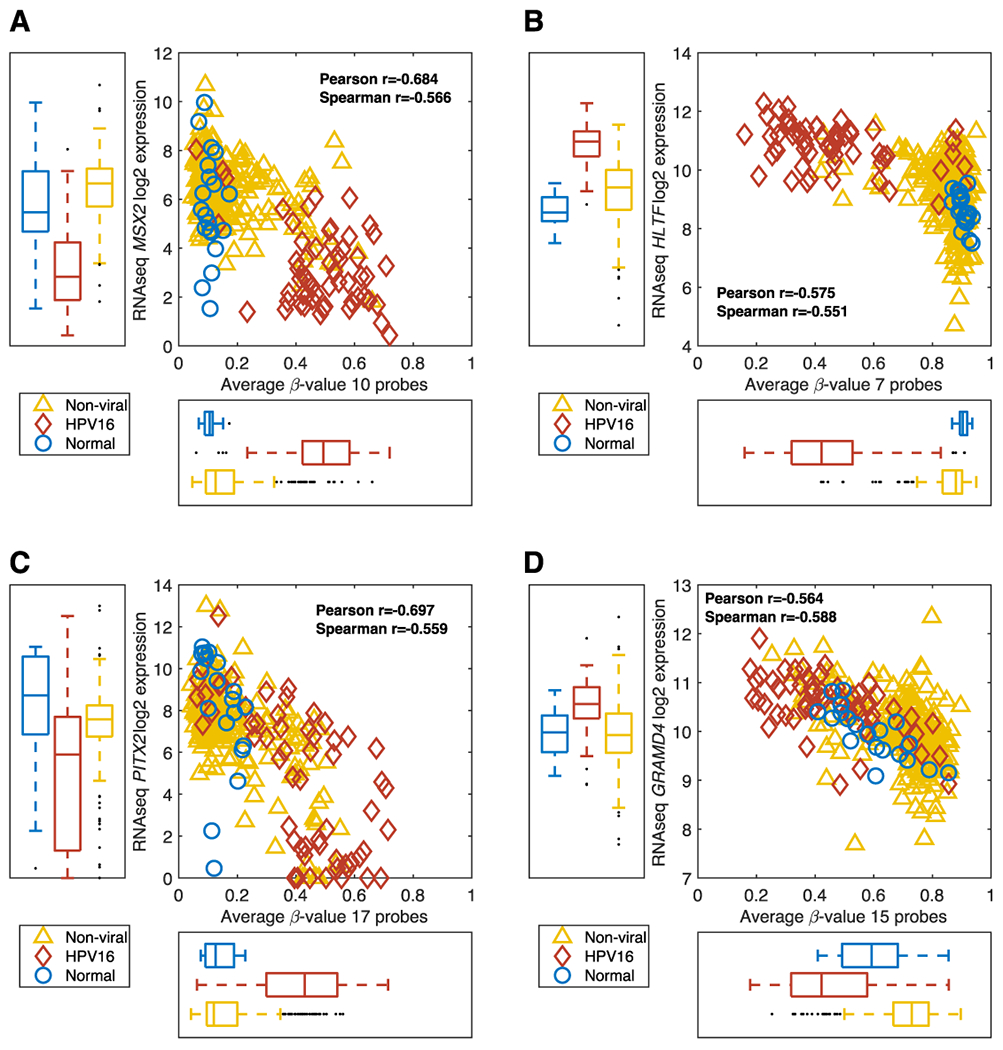

MSX2, HLTF, PITX2 and GRAMD4

Msh homeobox 2 (MSX2, 5q) is an example of a significantly differentially hypermethylated gene in HPV16+ samples as compared to non-viral tumors and normal tissue samples (Figure 4A). Hypermethylation was associated with lower expression of MSX2 in HPV16+ tumors. Differentially methylated probes are located in the TSS1500, TSS200, 5’UTR, 1stExon and in the gene-body regions of MSX2 (Supplementary Figure S1 A–C). Expression was impacted by copy number variation only in non-viral tumor samples (Supplementary Figure S1 D–E).

Figure 4. Genes with HPV16-Associated Methylation.

RNASeq gene expression vs. methylation level is shown for MSX2 (A), HLTF (B), PITX2 (C) and GRAMD4 (D) with HPV16+ tumors in red, non-viral tumors in yellow and normal tissue in blue.

Helicase like transcription factor (HLTF, 2p) exhibited similar methylation characteristics to SYCP2, with hypomethylation in HPV16+ tumors and hypermethylation in non-viral tumors and normal tissues (Figure 4B). All significant probes for HLTF were identified in the TSS1500 region and were negatively correlated with gene expression (Supplementary Figure S2 A–C). The expression of HLTF is also higher in HPV16+ tumors indicating that the expression of HLTF is at least in part regulated by methylation. Copy number variation influenced expression of HTLF in both non-viral and HPV16+ tumors (Supplementary Figure S2 D–E).

Paired like homeodomain 2 (PITX2, 4q) demonstrated hypermethylation in HPV16+ tumors with hypomethylation in normal tissues and most non-viral tumors (Figure 4C). For PITX2, 70 CpG-probes were identified on the Illumina 450K chip of which 17 were used for calculating the average methylation level for PITX2. (Supplementary Figure S3 A–C). Average methylation levels for PITX2 correlated with gene expression which was not impacted by copy number variations (Supplementary Figure S3 D–E).

GRAM domain containing 4 (GRAMD4, 22q) demonstrated hypomethylation in HPV16+ tumors and hypermethylation in non-viral tumors and normal tissues (Figure 4D). 15 probes for GRAMD4 were negatively correlated with gene expression was also correlated to each other (Supplementary Figure S4 A–C). GRAMD4 expression was impacted by copy number variations only in non-viral tumor samples (Supplementary Figure S4 D–E).

Derivation of PLS models

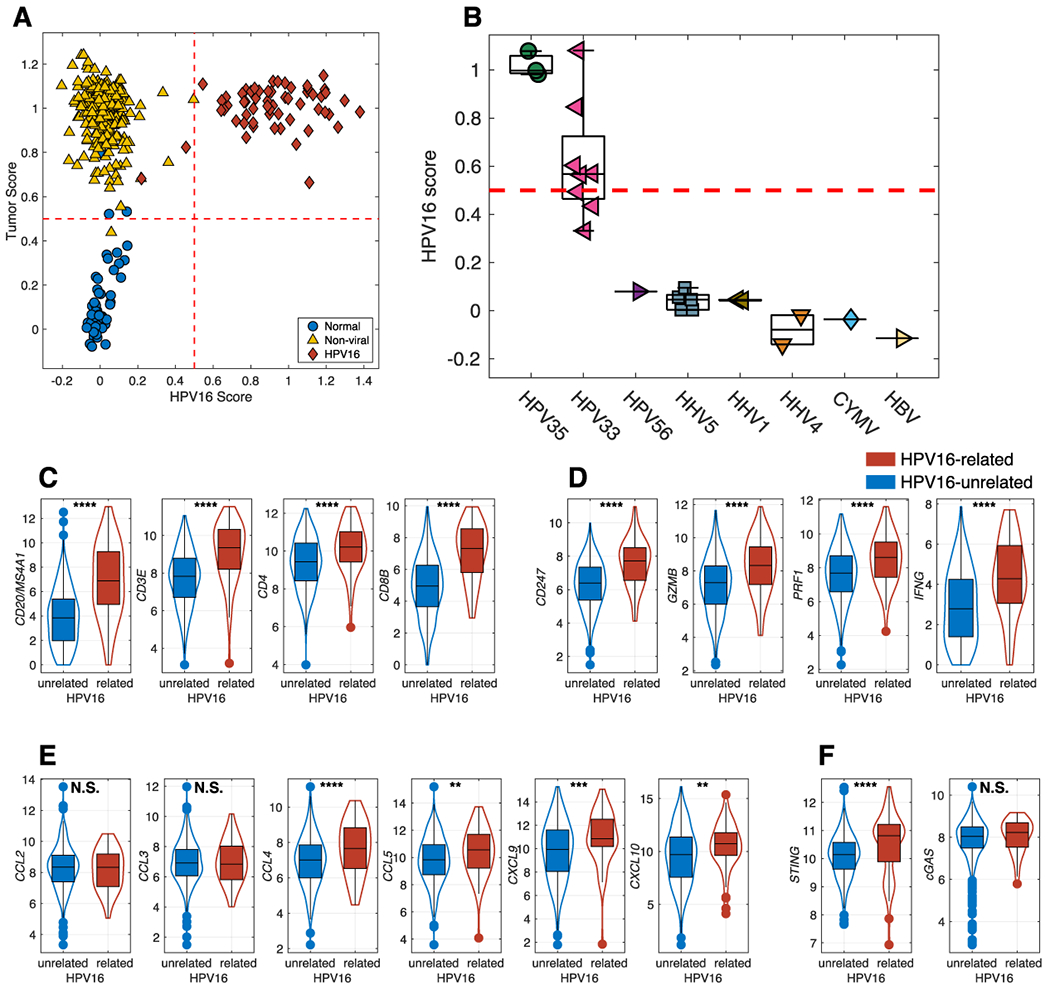

The HPV16+ PLS model (59 HPV16+ tumors and 238 non-viral tumors (all other virus types were excluded) was calculated using the 200 selected probes as described in the Methods section and listed in Supplementary Table S3. Cross-validation yielded two significant PLS components. The tumor vs. normal PLS model (50 normal samples and 297 tumor samples) was also calculated using 200 selected probes, as listed in Supplementary Table S3. Two significant PLS components were identified by cross-validation. The results from the training of these two PLS models are shown in Figure 5A. The HPV16+ PLS model score is plotted on the x-axis whereas the tumor vs. normal PLS score is plotted on the y-axis. In this 2-dimensional representation, normal tissue, HPV16+ tumors and non-viral tumors clearly separated into three quadrants.

Figure 5. HPV16 PLS predictions in HNSC.

The results of the PLS model are shown on the training set and shows a clear separation (A) of normal samples (blue circles), non-viral tumors (yellow up-triangles) and HPV16+ tumors (red diamonds). The HPV16+ PLS model also predicts HPV35 and 5 of the HPV33 tumors as being HPV16-related (B). Comparison of HPV16-related and HPV16-unrelated HNSCC, on T and B cells infiltration (C), T effector functions (D), Chemokines for immune cell trafficking (E) STING and cGAS (F) * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001.

Validation of PLS models in HNSCC.

In order to independently validate the PLS models, we applied the PLS model to samples not used in the training sets. We applied the HPV16+ PLS model to HNSCC samples from TCGA that were not used for derivation of the PLS model but with known viral status (Figure 5B). Five of the eight HPV33 tumor samples (pink left triangles) were scored as “HPV16-related” with the remaining 3 closely approaching the 0.5 cut-off value. All three HPV35 tumor samples (green circles) also were scored as HPV16-related. This demonstrates that these specific HPV types are associated with the methylation of a similar set of genes, a concept also suggested by the PCA analysis (Figure 1B). Notably, HPV16, HPV33 and HPV35 are closely related on the viral phylogenetic tree and fall within the alpha-9 species. All other virus types were scored as being unassociated with an HPV16-related profile.

Expression Markers of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

Tumor T-cell infiltration has been associated with favorable prognosis (37), HPV16+ tumors were associated with increased tumor infiltration by T cells (CD3E, CD4, CD8B) and B cells (MS4A1/CD20) with superior effector functions as demonstrated by elevated CD247, Granzyme B, and Perforin and IFNγ (Figure 5C, D). Increased TIL infiltration in HPV16+ tumors was associated with elevated levels of key chemokines that drive T cell recruitment and trafficking (Figure 5E) and a significant increase in STING expression (Figure 5F) which is a crucial molecule implicated in tumor immunogenicity (38)

Validation of PLS Models in Independent Cervical Cancer and HNSCC Datasets

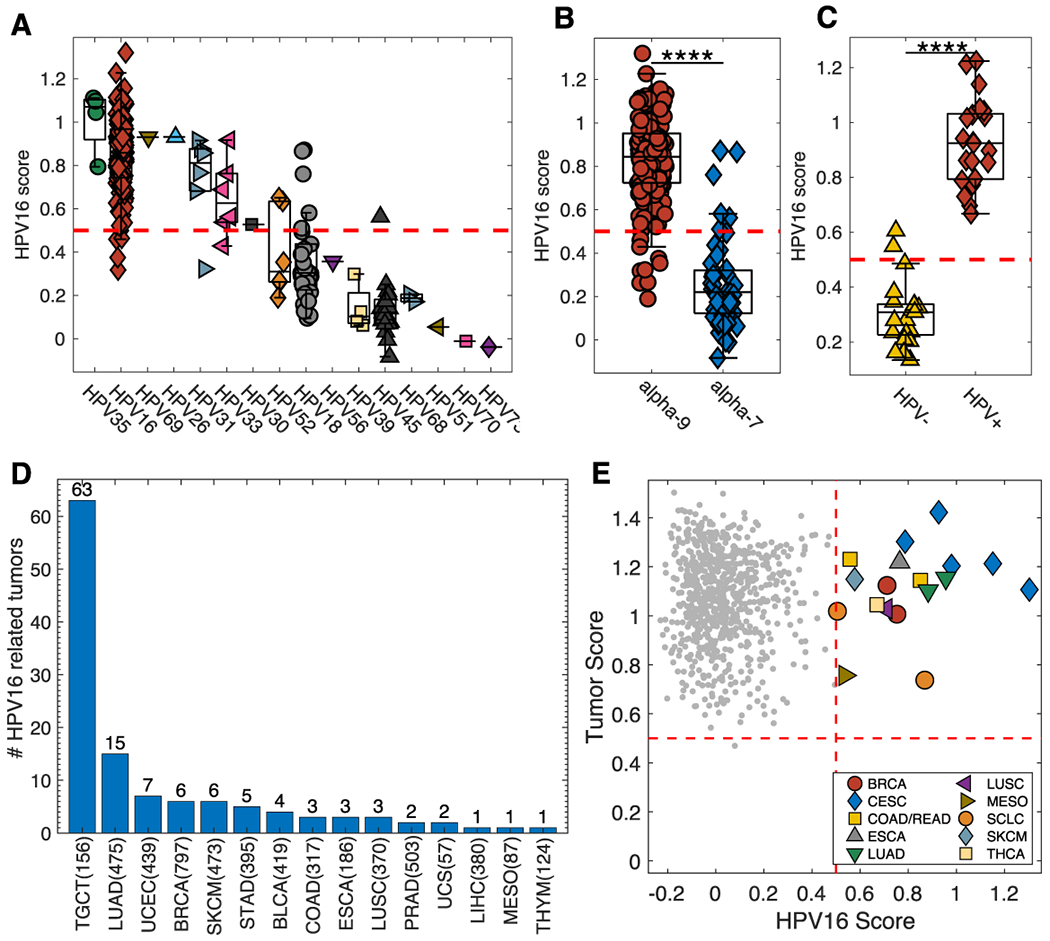

The HPV16+ PLS model was applied to the CESC (Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma) dataset from TCGA with similar annotation of HPV status (Figure 6A). 140 (96.6%) of 145 HPV16+ tumors were correctly scored as HPV16-related (red diamonds). Similar to the TCGA HNSCC data, all HPV35 tumors (n=4) were scored as HPV16-related along with five out of six for both HPV33 (pink left triangles) and HPV31 (blue right triangles) tumors. These three HPV types (HPV35, HPV33 and HPV31) are all alpha-9 viruses. Other virus types that scored predominantly as HPV16-like included: alpha-5 HPV26 1(1), alpha-6 HPV30 1(1), and alpha-5 HPV69 1(1). Interestingly, 25 (80.6%) of the 31 HPV18 tumors and 16 of 16 HPV45+ tumors were scored as HPV16-unrelated. This would indicate that methylation alterations associated with HPV18 and HPV45 (both alpha-7 species) are different from those seen with HPV16 and other alpha-9 counterparts. (Figure 6B). To further validate our HPV16+ PLS model, we applied it to the GSE38266 HNSCC dataset and demonstrate complete segregation between HPV− and HPV+ samples (Figure 6C). All HPV+ samples scored higher than 0.5 while two of the HPV− samples were noted to score slightly above 0.5.

Figure 6. HPV16+ PLS Model Prediction in CESC, HNSCC and Other Tumor Types.

The PLS model was also applied to the TCGA cervical cancer (CESC) dataset (A) demonstrating a general separation between HPV alpha-9 and alpha-7 species (B). Box Plot for HPV16+ PLS model prediction when applied to the GSE38266 HNSCC dataset (C). The HPV16+ PLS model applied to all tumor types from the TCGA Pan-Cancer dataset. (D) and demonstrates that 63 (40.4%) out of 156 testicular germ cell tumors (TCGT) and 15 (3.2%) of 475 lung adenocarcinoma samples (LUAD) are classified as HPV16-related. Applying the PLS models to CCLE shows that all cell lines but one are classified as tumors and that 18 of the cell lines scored as HPV16-related (E). **** p<0.0001; TGCT-Testicular Germ Cell Tumors, LUAD-Lung adenocarcinoma, UCEC-Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma, BRCA-Breast invasive carcinoma, SKCM-Skin Cutaneous Melanoma, STAD-Stomach adenocarcinoma, BLCA-Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma, COAD-Colon adenocarcinoma, ESCA-Esophageal carcinoma, LUSC-Lung squamous cell carcinoma, PRAD-Prostate adenocarcinoma, UCS-Uterine Carcinosarcoma, LIHC-Liver hepatocellular carcinoma, MESO-Mesothelioma, and THYM-Thymoma.

Other TCGA Cancer Samples

We also applied the HPV16+ PLS model to all remaining TCGA samples of all cancer types with available corresponding methylation profiling data (Figure 6D). Most notably, 63 (40.4%) of 156 testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT) were classified as HPV16-related along with 15 (3.2%) of 475 lung adenocarcinomas (LUAD).

PLS Models Applied to Cancer Cell Lines

Our HPV16+ and Tumor vs. Normal PLS models were applied to the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE). All but one sample were scored correctly as “Tumor” (Figure 6E) while 18 of the cell lines were classified as HPV16-related (Supplementary Table S4). These results suggest that the methylation changes in the selected probes are intrinsically associated with the tumor cell and not due to adjacent non-tumor cells (e.g. immune, stromal) in the pathologic specimen. Seven of the HPV16-related cell lines were of cervical cancer origin while six were derived from lung cancers.

DISCUSSION

Genome-wide alterations in methylation play a critical role in the development of numerous malignancies (39). Notably, it has also become increasingly apparent that these epigenetic events also contribute to the process of HPV-associated neoplastic progression, such as in a substantial number of head and neck malignancies (40). Although a number of studies have characterized methylation differences between HPV+ and HPV− head and neck cancers (19–24), a comprehensive evaluation of differences that includes normal head and neck mucosa (allowing for an evaluation of potential epigenetic contributors to carcinogenesis) and HPV16+ (rather than all HPV types together) and non-viral HNSCC has been lacking.

Our analyses provide greater insight with respect to the contribution of methylation events in the process of general tumorigenesis as opposed to those that are uniquely associated with HPV-related carcinogenesis. In this study, we leveraged TCGA genome-wide methylation data for normal tissue and HNSCC to generate a PLS model that uniquely classifies: 1) tumor vs. normal and 2) HPV16+ tumors vs. non-viral tumors. The PLS models provide insights into both shared and unique methylation alterations associated with normal tissue, HPV16+ and non-viral tumors in HNSCC. The HPV status and tumor versus normal PLS models were further validated in cervical squamous cell carcinoma (HPV+) from additional external datasets.

Our analysis also highlights variable patterns of epigenetic alterations between cancers associated with different HPV types. It is clear from both our PCA and PLS models that tumors infected with HPV16 have similar methylation patterns to tumors infected with HPV31, HPV33 and HPV35 (all alpha-9 species members) as compared to tumors infected with HPV18 and HPV45 (both alpha-7 species). (41)

When comparing HPV16+ and non-viral HNSCC, we identified 130 significant probes mapping to 57 genes, of which 4 (SYCP2, MXS2, HLTF and PITX2) have previously been reported to be associated with HNSCC.

SYCP2 is a testis-specific human gene with a protein product that is involved in chromosomal recombination during meiosis. We observed it to be differentially hypomethylated (with corresponding increase in gene expression) in HPV16+ versus non-viral HNSCC. This finding is concordant with several previous studies which have shown higher expression of SYCP2 in HPV-positive HNSCC as compared to pre-malignant/normal matched tissue samples, and HPV-negative HNSCC (42,43). SYCP2, along with another testis-specific gene testicular cell adhesion molecule 1 TCAM1, has been found to be upregulated in HPV-positive HNSCC by E6 and E7, the viral oncogenes of high-risk HPV (4,42). In a recent study, Tripathi et al. found that higher levels of SYCP2 expression were associated with improved survival in HNSCC (43). SYCP2 hypomethylation has been observed among numerous other cancers and may represent a candidate epigenetically-mediated driver of malignancy (43,44).

The MSX2 (MSH homeobox 2) protein is a transcription factor that plays a role in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival during development. Expression of this gene is low in most normal adult tissues but was found to be high in several human tumor cell lines (45). In colorectal cancer, MSX2 has been shown to have higher expression in tumor compared to normal colorectal tissue, and higher expression in tumor tissue was also negatively associated with prognosis (46). Studies of malignant melanoma and breast cancer tissues, however, demonstrated a positive association between increased MSX2 expression and prognosis (47). In HNSCC, MSX2 has been shown to be differentially hypermethylated in HPV-positive versus HPV-negative tumors (34). Our findings are consistent with these previous studies, with MSX2 being hypermethylated in HPV16+ tumors (with a corresponding reduction in gene expression) compared to non-viral HNSCC and normal tissues.

Supplementary Figure 1A illustrates that not all probes for MSX2 were significantly differentially methylated, especially those in non-promoter regions. Genes with significant differential methylation in non-promoter regions, such as the gene body, often showed no gene expression differences in HPV16+ versus non-viral HPV tumors. This exemplifies the importance of using gene-level information when examining the location of differential methylation, as this may influence the selection of biologically significant epigenetically-mediated biomarkers.

HLTF (Helicase-like Transcription Factor), which belongs to the SWI/SNF family of proteins, is a DNA helicase involved with chromatin remodeling and DNA-damage repair. Hypermethylation of the HLTF gene promoter has been reported in more than 40% of colon cancers, as well as in gastric and esophageal cancers (48–50). In colon cancers, HLTF hypermethylation and decreased expression has been associated with increased tumor growth and genomic instability, as well as with poor prognosis (49,50). In HNSCC, Capouillez et al. found that HLTF expression was associated with neoplastic progression (48). HLFT expression was also found to predict recurrence in hypopharyngeal (although not laryngeal) SCC (48). Our study appears to be the first to show that HLTF is differentially hypomethylated (with increased expression) in HPV16+ versus non-viral HNSCC and normal tissue.

PITX2 (Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2) is a transcription factor that plays an essential role in embryonic development, with involvement in tissue-specific cell proliferation, morphogenesis and development of left-right asymmetry. High PITX2 expression has been found in colorectal cancers and other WNT/beta-catenin aberrant pathway tumors such as esophageal SCC (51). Low methylation/overexpression of PITX2 has been associated with tumor progression in thyroid and ovarian cancer, while hypermethylation has been found in AML (acute myeloid leukemia) and is associated with increased risk of disease in non-small cell lung cancer. Hypermethylation of PITX2 has been correlated with HPV-positive status, lower tumor grade and improved overall survival in HNSCC (51). Differential hypermethylation of PITX2 in HPV-positive versus HPV-negative HNSCC was demonstrated by Lechner et al (34). Our findings that PITX2 is hypermethylated in HPV16+ HNSCC vs non-viral HNSCC and normal tissue, are congruent with these previous studies.

GRAMD4 (Gram domain-containing protein 4), has not been previously reported to be associated with HNSCC. Also known as death-inducing protein (DIP), this gene is involved in apoptosis. We found that GRAMD4 is hypomethylated in HPV16+ HNSCC compared to non-viral HNSCC and normal tissue. This gene has previously been found to mimic the tumor-suppressive function of p53. However, it has also been found to have higher expression in hepatocellular cancer cell lines compared to normal liver cell lines (52), as well as in lung squamous cell carcinoma vs normal lung tissue (53). Our identification of this gene provides impetus for further investigation of its associations with HPV-associated HNSCC and its oncogenic mechanisms of action.

The effects of HPV in HNSCC including response to immunotherapy was recently reviewed by Lechien et al.(54). Our observations of signals of increased immune activation in this setting are concordant with previous reports of increased activation of T-cells and chemokines (55). Decreased expression levels of CXCL10, CXCL9, GZMB, PRF1, IFNG, CD8A have been linked to worse outcomes (56). The overexpression of both gene and protein levels of STING in HPV+ tumors, as compared to HPV− tumors, is well established (57,58)

The role of HPV16 in testicular germ cell tumorigenesis remains debatable. Studies investigating the association of HPV and testicular cancer have been sparse. Two meta-analyses by Garolla et al. and Heidegger I et al. (59,60) reviewed HPV− and TGCT-related publications and their findings were inconclusive due to the small number of available studies. A total of five studies focused on investigating the association of HPV and TGCTs have been reported. An epidemiologic study by Strickler et al. demonstrated that only 5% of testicular cancers were positive for HPV16 (61). Garolla et al. demonstrated that in 155 testicular cancer patients there was a significantly higher prevalence of HPV-infected semen as compared to controls (9.5% and 2.4% respectively), however, the HPV status of these tumors were not directly investigated (62). Animal studies by Kondoh et al. using transgenic mice carrying HPV16 E6 and E7 open reading frames demonstrated a high incidence of TGCT that were invariably HPV16-positive (63). In contrast to these findings, in a study of in testicular seminomas (n=61) and normal tissues (n=23), HPV16 and HPV18 genotypes were not detected (64). Concordantly, Rajpert-De Meyts et al. demonstrated that HPV was not detected in a cohort of 22 TGCTs (65). reviewed HPV− and TGCT-related publications and their findings were inconclusive due to the small number of available studies. A total of five studies focused on investigating the association of HPV and TGCTs have been reported. An epidemiologic study by Strickler et al. demonstrated that only 5% of testicular cancers were positive for HPV16 (61). Garolla et al. demonstrated that in 155 testicular cancer patients there was a significantly higher prevalence of HPV infected semen as compared to controls (9.5% and 2.4% respectively), however, the HPV status of these tumors were not directly investigated (62). Animal studies by Kondoh et al. using transgenic mice carrying HPV16 E6 and E7 open reading frames demonstrated a high incidence of TGCT that were invariably HPV16-positive (63). In contrast to these findings, in a study of in testicular seminomas (n=61) and normal tissues (n=23), HPV16 and HPV18 genotypes were not detected (64). Concordantly, Rajpert-De Meyts et al. demonstrated that HPV was not detected in a cohort of 22 TGCTs (65). By application of our PLS model to the TGCT specimens from TCGA, we demonstrated that 40% of TGCTs displayed a clear HPV16-related methylation profile (Figure 6C). The role of HPV in testicular cancer tumorigenesis remains controversial due to the limited number of studies. Further investigations are clearly warranted to better elucidate this association.

Similarly, although to a lesser degree, we observed that handful of lung adenocarcinoma samples (3.2%) were classified as HPV16-related by our PLS model. Notably Cao et al. examined RNASeq data from TCGA and did not detect any HPV16 or other HPV types in any lung adenocarcinoma samples (25). To examine whether smoking status could be a potential confounder in our TCGA HNSCC cohort, we did examine HPV16 PLS scoring in smokers vs. non-smokers and demonstrated no differences. As such, it remains unclear as to the significance of an HPV16-like methylation profile among lung adenocarcinomas.

As previously noted, it is well established that HPV+ HNSCC have more favorable clinical outcomes and response to treatment as compared to HPV− counterparts; however, there remains a small but significant subset of approximately 20% of HPV+ cancers that appear more treatment-resistant and with a worse prognosis. (15) Our observations suggest that differences in the HPV-driven epigenotype may provide some underlying molecular explanations to the differences in clinical behavior. Furthermore, there is still nonetheless, heterogeneity among HPV+ HNSCC (which are frequently defined by p16-positivity rather than genotyping). Variable HPV type-related methylomic changes may at least, in part, contribute to such differences. Nakagawa et al. have reported a high-DNA methylation subtype in HPV+ oropharyngeal SCC that was associated with good prognosis. (20) Our findings support the notion that HPV infection results in type-specific biologically significant methylomic changes that may account for observed differences in response to treatment and prognosis in HNSCC.

The emerging importance of DNA methylation changes in the development of HNSCC has also led the recognition of their potential as biomarkers for a number of translational clinical applications. From a screening standpoint, there has been significant interest in developing novel/efficient methods of detecting pre-malignant head and neck or HNSCC at the earliest of stages. There has been evidence to suggest that strategies such as the identification of molecular alterations in oral gargle specimens may hold promise. Indeed, methylation in selected genes have been detectable in such specimens from HPV+ HNSCC patients.(66). More recently, the emergence of reliable circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection techniques has also allowed for the identification of methylation changes in patient blood. As an example, Misawa et al. demonstrated that a panel of 3 methylated genes were detectable in the plasma of patients with HPV+ HNSCC. (67) As noted, previous studies have suggested that there are important differences in methylation changes between HPV− and HPV+ HNSCC that could allow for etiology-specific detection panels for various platforms. However, our findings are relevant in highlighting that such changes actually vary depending on not only HPV infection in general but also, the underlying HPV type and have implications for more accurate detection panels. In addition to applications in screening, specific DNA methylation signatures (e.g.., HPV-type-specific) may serve as more refined biomarkers for treatment strategies such as de-escalation and patient prognosis. Broad de-methylating treatment agents such as 5azaDC have been long used in hematologic malignancies and are the subject of HNSCC-related clinical trials. However, further understanding of epigenetically-mediated carcinogenic elements and pathways may yield novel targeted strategies for therapy and/or enhancement of treatment sensitivity.

Translational development of such findings will require further both mechanistic/biologic and broader validating investigations related to the differential methylation in HPV− and HPV+ type-specific HNSCC which may in turn, lead to the identification of novel strategies for prevention, early diagnosis, surveillance and personalized treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This project has been supported in part, by grant R21-CA185921 (DS/ES) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The results generated are in part, based upon data available from the TCGA Research Network: https://www.cancer.gov/tcga. This work has been supported in part, by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Abbreviations in Manuscript:

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas

- OPSCC

oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- PCA

Principal Component Analysis

- PLS

Partial Least Squares

- CpG

5’-C-phosphate-G-3’

- DMR

Differently Methylated Region

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- CESC

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- CCLE

Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia

- FDR

False Discovery Rate

- TGCT

Testicular Germ Cell Tumors

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HHV

Human Herpes virus

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE:

The authors declare no potential conflict in interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Head and Neck Cancer v1; 2017. Available from: . https://wwwnccnorg/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelinesasp#site.

- 2.Pytynia KB, Dahlstrom KR, Sturgis EM. Epidemiology of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Oral oncology 2014;50(5):380–6 doi 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman TA, Schiller JT. Human papillomavirus in cervical cancer and oropharyngeal cancer: One cause, two diseases. Cancer 2017;123(12):2219–29 doi 10.1002/cncr.30588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pannone G, Santoro A, Papagerakis S, Lo Muzio L, De Rosa G, Bufo P. The role of human papillomavirus in the pathogenesis of head & neck squamous cell carcinoma: an overview. Infectious agents and cancer 2011;6:4 doi 10.1186/1750-9378-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pai SI, Westra WH. Molecular pathology of head and neck cancer: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Annual review of pathology 2009;4:49–70 doi 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirghani H, Amen F, Tao Y, Deutsch E, Levy A. Increased radiosensitivity of HPV-positive head and neck cancers: Molecular basis and therapeutic perspectives. Cancer treatment reviews 2015;41(10):844–52 doi 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson GA, Lechner M, Koferle A, Caren H, Butcher LM, Feber A, et al. Integrated virus-host methylome analysis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Epigenetics 2013;8(9):953–61 doi 10.4161/epi.25614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dok R, Nuyts S. HPV Positive Head and Neck Cancers: Molecular Pathogenesis and Evolving Treatment Strategies. Cancers 2016;8(4) doi 10.3390/cancers8040041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soto D, Song C, McLaughlin-Drubin ME. Epigenetic Alterations in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers. Viruses 2017;9(9) doi 10.3390/v9090248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durzynska J, Lesniewicz K, Poreba E. Human papillomaviruses in epigenetic regulations. Mutation research Reviews in mutation research 2017;772:36–50 doi 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsay C, Seikaly H, Biron VL. Epigenetics of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: opportunities for novel chemotherapeutic targets. Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = Le Journal d’oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale 2017;46(1):9 doi 10.1186/s40463-017-0185-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sartor MA, Dolinoy DC, Jones TR, Colacino JA, Prince ME, Carey TE, et al. Genome-wide methylation and expression differences in HPV(+) and HPV(−) squamous cell carcinoma cell lines are consistent with divergent mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Epigenetics 2011;6(6):777–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2007;121(8):1813–20 doi 10.1002/ijc.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taberna M, Mena M, Pavon MA, Alemany L, Gillison ML, Mesia R. Human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol 2017;28(10):2386–98 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdx304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363(1):24–35 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2015;33(29):3235–42 doi 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephen JK, Worsham MJ. Human papilloma virus (HPV) modulation of the HNSCC epigenome. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2015;1238:369–79 doi 10.1007/978-1-4939-1804-1_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Kempen PM, Noorlag R, Braunius WW, Stegeman I, Willems SM, Grolman W. Differences in methylation profiles between HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Epigenetics 2014;9(2):194–203 doi 10.4161/epi.26881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer Genome Atlas N Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature 2015;517(7536):576–82 doi 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa T, Matsusaka K, Misawa K, Ota S, Fukuyo M, Rahmutulla B, et al. Stratification of HPV-associated and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas based on DNA methylation epigenotypes. Int J Cancer 2020;146(9):2460–74 doi 10.1002/ijc.32890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degli Esposti D, Sklias A, Lima SC, Beghelli-de la Forest Divonne S, Cahais V, Fernandez-Jimenez N, et al. Unique DNA methylation signature in HPV-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Genome Med 2017;9(1):33 doi 10.1186/s13073-017-0419-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papillon-Cavanagh S, Lu C, Gayden T, Mikael LG, Bechet D, Karamboulas C, et al. Impaired H3K36 methylation defines a subset of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet 2017;49(2):180–5 doi 10.1038/ng.3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ando M, Saito Y, Xu G, Bui NQ, Medetgul-Ernar K, Pu M, et al. Chromatin dysregulation and DNA methylation at transcription start sites associated with transcriptional repression in cancers. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):2188 doi 10.1038/s41467-019-09937-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parfenov M, Pedamallu CS, Gehlenborg N, Freeman SS, Danilova L, Bristow CA, et al. Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(43):15544–9 doi 10.1073/pnas.1416074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao S, Wendl MC, Wyczalkowski MA, Wylie K, Ye K, Jayasinghe R, et al. Divergent viral presentation among human tumors and adjacent normal tissues. Sci Rep 2016;6:28294 doi 10.1038/srep28294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang KW, Alaei-Mahabadi B, Samuelsson T, Lindh M, Larsson E. The landscape of viral expression and host gene fusion and adaptation in human cancer. Nat Commun 2013;4:2513 doi 10.1038/ncomms3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Koestler DC, Karagas MR, Flanagan JM, Christensen BC, Kelsey KT, et al. Review of processing and analysis methods for DNA methylation array data. Br J Cancer 2013;109(6):1394–402 doi 10.1038/bjc.2013.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99(6):3740–5 doi 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berglund AE, Putney RM, Creed JH, Aden-Buie G, Gerke TA, Rounbehler RJ. Accessible Pipeline for Translational Research Using TCGA: Examples of Relating Gene Mechanism to Disease-Specific Outcomes. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2021;2194:127–42 doi 10.1007/978-1-0716-0849-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berglund A, Mills M, Putney RM, Hamaidi I, Mule J, Kim S. Methylation of immune synapse genes modulates tumor immunogenicity. J Clin Invest 2020;130(2):974–80 doi 10.1172/JCI131234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol 2011;12(4):R41 doi 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iorio F, Knijnenburg TA, Vis DJ, Bignell GR, Menden MP, Schubert M, et al. A Landscape of Pharmacogenomic Interactions in Cancer. Cell 2016;166(3):740–54 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feber A, Arya M, de Winter P, Saqib M, Nigam R, Malone PR, et al. Epigenetics markers of metastasis and HPV-induced tumorigenesis in penile cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21(5):1196–206 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lechner M, Fenton T, West J, Wilson G, Feber A, Henderson S, et al. Identification and functional validation of HPV-mediated hypermethylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Genome Med 2013;5(2):15 doi 10.1186/gm419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lechner M, Frampton GM, Fenton T, Feber A, Palmer G, Jay A, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma identifies novel genetic alterations in HPV+ and HPV-tumors. Genome Med 2013;5(5):49 doi 10.1186/gm453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2012;2(5):401–4 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vassilakopoulou M, Avgeris M, Velcheti V, Kotoula V, Rampias T, Chatzopoulos K, et al. Evaluation of PD-L1 Expression and Associated Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22(3):704–13 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konno H, Yamauchi S, Berglund A, Putney RM, Mule JJ, Barber GN. Suppression of STING signaling through epigenetic silencing and missense mutation impedes DNA damage mediated cytokine production. Oncogene 2018;37(15):2037–51 doi 10.1038/s41388-017-0120-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Youn A, Kim KI, Rabadan R, Tycko B, Shen Y, Wang S. A pan-cancer analysis of driver gene mutations, DNA methylation and gene expressions reveals that chromatin remodeling is a major mechanism inducing global changes in cancer epigenomes. BMC Med Genomics 2018;11(1):98 doi 10.1186/s12920-018-0425-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colacino JA, Dolinoy DC, Duffy SA, Sartor MA, Chepeha DB, Bradford CR, et al. Comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma indicates differences by survival and clinicopathologic characteristics. PloS one 2013;8(1):e54742 doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0054742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 2004;324(1):17–27 doi 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pyeon D, Newton MA, Lambert PF, den Boon JA, Sengupta S, Marsit CJ, et al. Fundamental differences in cell cycle deregulation in human papillomavirus-positive and human papillomavirus-negative head/neck and cervical cancers. Cancer Res 2007;67(10):4605–19 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tripathi N, Keshari S, Shahi P, Maurya P, Bhattacharjee A, Gupta K, et al. Human papillomavirus elevated genetic biomarker signature by statistical algorithm. J Cell Physiol 2020;235(12):9922–32 doi 10.1002/jcp.29807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saghafinia S, Mina M, Riggi N, Hanahan D, Ciriello G. Pan-Cancer Landscape of Aberrant DNA Methylation across Human Tumors. Cell Rep 2018;25(4):1066–80 e8 doi 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi C, Akiyama N, Matsuzaki T, Takai S, Kitayama H, Noda M. Characterization of a human MSX-2 cDNA and its fragment isolated as a transformation suppressor gene against v-Ki-ras oncogene. Oncogene 1996;12(10):2137–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu JC, An HY, Yuan W, Feng Q, Chen LZ, Ma J. Prognostic Relevance and Function of MSX2 in Colorectal Cancer. J Diabetes Res 2017;2017. doi Artn 3827037 10.1155/2017/3827037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gremel G, Ryan D, Rafferty M, Lanigan F, Hegarty S, Lavelle M, et al. Functional and prognostic relevance of the homeobox protein MSX2 in malignant melanoma. Br J Cancer 2011;105(4):565–74 doi 10.1038/bjc.2011.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capouillez A, Debauve G, Decaestecker C, Filleul O, Chevalier D, Mortuaire G, et al. The helicase-like transcription factor is a strong predictor of recurrence in hypopharyngeal but not in laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Histopathology 2009;55(1):77–90 doi 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasmussen SL, Krarup HB, Sunesen KG, Pedersen IS, Madsen PH, Thorlacius-Ussing O. Hypermethylated DNA as a biomarker for colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2016;18(6):549–61 doi 10.1111/codi.13336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandhu S, Wu X, Nabi Z, Rastegar M, Kung S, Mai S, et al. Loss of HLTF function promotes intestinal carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer 2012;11:18 doi 10.1186/1476-4598-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sailer V, Holmes EE, Gevensleben H, Goltz D, Droge F, de Vos L, et al. PITX2 and PANCR DNA methylation predicts overall survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016;7(46):75827–38 doi 10.18632/oncotarget.12417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Tu K, Zhou Z, Zheng X, Gao J, Yao Y, et al. [Expression and clinicopathological significance of GRAMD4 in hepatocellular carcinoma]. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013;29(2):190–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sen S, Ateeq B, Sharma H, Datta P, Gupta SD, Bal S, et al. Molecular profiling of genes in squamous cell lung carcinoma in Asian Indians. Life Sci 2008;82(13-14):772–9 doi 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lechien JR, Descamps G, Seminerio I, Furgiuele S, Dequanter D, Mouawad F, et al. HPV Involvement in the Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Treatment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Cancers 2020;12(5) doi 10.3390/cancers12051060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng H, Song X, Ji J, Chen L, Liao Q, Ma X. HPV infection related immune infiltration gene associated therapeutic strategy and clinical outcome in HNSCC. BMC Cancer 2020;20(1):796 doi 10.1186/s12885-020-07298-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huo M, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Zhang S, Bao Y, Li T. Tumor microenvironment characterization in head and neck cancer identifies prognostic and immunotherapeutically relevant gene signatures. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):11163 doi 10.1038/s41598-020-68074-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saulters E, Woolley JF, Varadarajan S, Jones TM, Dahal LN. STINGing Viral Tumors: What We Know from Head and Neck Cancers. Cancer Res 2021;81(15):3945–52 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu S, Concha-Benavente F, Shayan G, Srivastava RM, Gibson SP, Wang L, et al. STING activation enhances cetuximab-mediated NK cell activation and DC maturation and correlates with HPV(+) status in head and neck cancer. Oral oncology 2018;78:186–93 doi 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garolla A, Vitagliano A, Muscianisi F, Valente U, Ghezzi M, Andrisani A, et al. Role of Viral Infections in Testicular Cancer Etiology: Evidence From a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:355 doi 10.3389/fendo.2019.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heidegger I, Borena W, Pichler R. The role of human papilloma virus in urological malignancies. Anticancer Res 2015;35(5):2513–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strickler HD, Schiffman MH, Shah KV, Rabkin CS, Schiller JT, Wacholder S, et al. A survey of human papillomavirus 16 antibodies in patients with epithelial cancers. Eur J Cancer Prev 1998;7(4):305–13 doi 10.1097/00008469-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garolla A, Pizzol D, Bertoldo A, Ghezzi M, Carraro U, Ferlin A, et al. Testicular cancer and HPV semen infection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:172 doi 10.3389/fendo.2012.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kondoh G, Murata Y, Aozasa K, Yutsudo M, Hakura A. Very high incidence of germ cell tumorigenesis (seminomagenesis) in human papillomavirus type 16 transgenic mice. J Virol 1991;65(6):3335–9 doi 10.1128/JVI.65.6.3335-3339.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bertazzoni G, Sgambato A, Migaldi M, Grottola A, Sabbatini AM, Nanni N, et al. Lack of evidence for an association between seminoma and human papillomavirus infection using GP5+/GP6+ consensus primers. J Med Virol 2013;85(1):105–9 doi 10.1002/jmv.23431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajpert-De Meyts E, Hording U, Nielsen HW, Skakkebaek NE. Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus in the etiology of testicular germ cell tumours. Apmis 1994;102(1):38–42 doi 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1994.tb04842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eggersmann TK, Baumeister P, Kumbrink J, Mayr D, Schmoeckel E, Thaler CJ, et al. Oropharyngeal HPV Detection Techniques in HPV-associated Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res 2020;40(4):2117–23 doi 10.21873/anticanres.14170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Misawa K, Imai A, Matsui H, Kanai A, Misawa Y, Mochizuki D, et al. Identification of novel methylation markers in HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: genome-wide discovery, tissue verification and validation testing in ctDNA. Oncogene 2020;39(24):4741–55 doi 10.1038/s41388-020-1327-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.