Abstract

There is no previous study that investigated the association between dietary intake of total and individual branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and odds of sarcopenia. The present study aimed to examine the association between dietary intake of BCAAs and sarcopenia and its components among Iranian adults. The data for this cross-sectional study was collected in 2011 among 300 older people (150 men and 150 female) with aged ≥ 55 years. We used a Block-format 117-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to evaluate usual dietary intakes. BCAAs intake was calculated by summing up the amount of valine, leucine and isoleucine intake from all food items in the FFQ. The European Sarcopenia Working Group (EWGSOP) definition was used to determine sarcopenia and its components. Mean age of study participants was 66.8 years and 51% were female. Average intake of BCAAs was 12.8 ± 5.1 g/day. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its components was not significantly different across tertile categories of total and individual BCAAs intake. We found no significant association between total BCAAs intake and odds of sarcopenia (OR for comparison of extreme tertiles 0.48, 95% CI 0.19–1.19, P-trend = 0.10) and its components (For muscle mass 0.83, 95% CI 0.39–1.77, P-trend = 0.63; for hand grip strength 0.81, 95% CI 0.37–1.75, P-trend: 0.59; for gait speed 1.22, 95% CI 0.58–2.57, P-trend = 0.56). After adjusting for potential confounders, this non-significant relationship did not alter. In addition, we did not find any significant association between individual BCAAs intake and odds of sarcopenia or its components. We found no significant association between dietary intakes of BCAAs and sarcopenia in crude model (OR 0.60; 95% CI 0.29–1.26). After controlling for several potential confounders, the result remained insignificant (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.19–1.19). In this cross-sectional study, no significant association was observed between dietary intakes of total and individual BCAAs and odds of sarcopenia and its components.

Subject terms: Nutrition, Quality of life

Introduction

Sarcopenia is a geriatric syndrome determined by a progressive and generalized decline in muscle mass, strength and function that associated reduce physical performance, poor quality of life and increased mortality1–3. As the global population ages, sarcopenia is becoming a crucial global public health problem4. The prevalence of this syndrome is estimated at 1 to 29% in Western countries and 2 to 49% in Asia5–7. Sarcopenia imposes significant costs on health care systems, as Janssen et al. estimated that sarcopenia-related annual health care costs in the United States are approximately $ 18 billion8.

Various factors have been confirmed to be associated with sarcopenia, including hormonal causes9, genetic10, physical activity11, and nutrients such as protein consumption12. In fact, protein affects muscle performance by stimulation and regulation of protein synthesis in muscles, where branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs; leucine, valine, and isoleucine) are metabolized13–15. Prior studies using European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) have shown that sarcopenia is associated with decreased concentrations of BCAAs, leucine and essential amino acids16, 17. In addition, supplementation with BCAAs, leucine and/or essential amino acids, resulted in increased protein synthesis in muscle in the elderly18–21. However, as far as we know, no previous study has investigated the association between dietary intakes of BCAAs and risk of sarcopenia.

As health conditions improve and life expectancy increases, the population around the world tends to age22. The prevalence of sarcopenia is higher in Asian adults than that in westerns7, 23. Importantly, the lifestyle and dietary patterns of people in the Middle East are different from those in Western populations24, 25. Main dishes in these countries contain high amounts of refined grains, including rice and bread, and dietary sources of protein do not contribute so much to total energy intake24, 25. Therefore, dietary intake of BCAAs in this area might be lower than that in western countries. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the association of BCAAs with sarcopenia and its components among Iranian adults.

Study participants and methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Tehran, Iran from May to October 2011. Details of the study design, sampling and data collection process were published previously26. A total of 300 elderly people (150 males and 150 females) aged 50 and older were selected by cluster random sampling method in District 6 of Tehran. The heads of each of the 30 clusters were selected according to a 10-digit postal code. In order to ensure the homogeneity of our sample, we did not include individuals with a predisposing cause of sarcopenia with factors other than aging27. In other words, people with limited mobility and a history of debilitating diseases such as active cancer, organ failure were not included. Also, people who could not walk without crutches, walkers or assistive devices, or had artificial limbs or prostheses were not included in the study because their lower muscle mass was not comparable to the muscle mass of the general population. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. All participants gave their written informed consent form before data collection.

Assessment of dietary intake

We applied a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to gather the information about usual dietary intakes of subjects. Participants were requested to report their usual dietary intakes of all foods included in the questionnaire in the preceding year based on daily, weekly or monthly consumption. The questionnaire was a validated one containing 117-food items in Block format. Consumption of foods and nutrients in the preceding year can reflect long-term usual dietary intake, as shown by nutritional epidemiologists28. Detailed information on this questionnaire has been reported elsewhere25, 26. In addition to the list of food items in the questionnaire, we had included a standard portion size for each item, portion sizes that were generally used by Iranians. Moreover, a frequency response section was also available for food items, in which participants were able to report their consumption of that food item. All the questionnaires were filled in a face-to-face interview by a trained nutritionist. In this interview, the nutritionist was asking the participants to recall and report their consumption of each food item in the questionnaire based on their usual intake in daily, weekly or monthly basis during the last year. Then, all frequencies were changed to daily intake and given the portion sizes of each food item, we converted all the reported foods into grams per day using a booklet of household measures29. In order to estimate mean energy and nutrient intakes for each study subject, a modified version of Nutritionist IV software (version 7.0; N-Squared Computing, Salem, OR, USA) was applied30. The database of this software had been modified based on the nutrient composition for available Iranian food items. Local foods had also been added to that database.

Dietary intake of BCAAs was calculated by summing up valine, leucine, and isoleucine values in 100 g of each food item for each participant. The main dietary sources contained these amino acids were dairy products, meat, and poultry.

Assessment of sarcopenia

We used the criteria recommended by the European Working Group in Older People (EWGSOP) to define sarcopenia. In that guideline, sarcopenia has been defined as the existence of both low muscle mass and low muscular strength or low physical performance27. In order to calculate muscle mass, first we computed lean mass of the legs and hands (named as Appendicular Skeletal Muscle or ASM) and then through dividing this to height squared (ASM/height2), we obtained total muscle mass for each study participant31. ASM was evaluated via DEXA scanner (Discovery W S/N 84430). According to the thresholds defined in the EWGSOP, low muscle mass was considered as < 5.45 (kg/m2) for women and < 7.26 (kg/m2) for men27. Muscle strength was assessed by hand grip strength, which was measured by a squeeze bulb dynamometer (c7489-02 Rolyan) calibrated in pound per square inch (psi). The hand grip strength was measured while subjects were sitting in a straight back seat with the shoulders were abducted in the neutral position of the arms and the elbow angle was approximately 90°. Participants in this position had a neutral arm rotation and their wrists deviated from 0° to 30° flexion and 0 to 15 °C. Participants were requested to squeeze the dynamometer as hard as possible for 10 to 30 s. The hand grip strength was assessed for each right and left hand three times with a 30-s rest between measurements. Mean of these three measurements for each hand was considered eventually. Then, by summing up the mean values for both hands, muscle strength was obtained. Low levels of muscle strength was defined according to the age- and gender-specific cut-off points suggested by Merkies et al.32. To evaluate the muscle function test, each participant was asked to walk at a normal speed until the end of a 4-m straight course. We recorded the time in seconds with a chronometer27. Participants who had gait speeds less than 0.8 m/s were considered as those with low muscle performance27.

Assessment of other variables

Required data on other variables such as demographic characteristics (including age, gender, education and occupation), past medical history and medication use, alcohol intake and smoking status was collected via pretested questionnaires. In order to assess the level of physical activity, the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used, in which the metabolic equivalents-hour per week (MET-h/week) was computed to state the activity level for each study participant. The validity of IPAQ has already been examined in the elderly population33. Weight was measured using a digital scale with light clothing. Height was assessed by a wall-mounted tape-meter in standing position without shoes. We measured waist circumference (WC) at the middle of the lower rib margin and iliac crest while people were standing and breathing normally. Finally, body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by the square of height.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, version 16.0). P values < 0.05 were identified as statistically significant. Initially, the third cut-off points for BCAA, valine, leucine and isoleucine diet were defined in the control group. Then all study participants were classified according to these cut-offs. To compare the general characteristics and dietary intakes across tertiles of BCAAs, we applied one-way ANOVA and chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. In order to find the association between BCAAs and odds of sarcopenia and its components, multivariate logistic regression analysis were applied. First, we adjusted for age (continuous), gender (male/female) and total energy intake (kcal/day). In a second model, we applied further adjustment for physical activity (MET-h/week, continues), smoking status (yes/no), alcohol intake (yes/no), medication use (statin, corticosteroid, estrogen, testosterone), and positive history of chronic disease. All models were applied by treating the first tertile of BCAAs as the reference. In order to determine the trend of odds ratios (ORs) across increasing tertiles of BCAAs, the tertiles were considered as an ordinal variable in the logistic regression models.

Results

In our study population, average intakes of BCAAs, valine, leucine and isoleucine were 12.86 ± 5.18, 4.03 ± 1.65, 5.49 ± 2.25 and 3.33 ± 1.32 g/day, respectively. General characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. We found that participants with sarcopenia had a lower BMI than healthy participants. There were no notable differences in other variables between people with and without sarcopenia.

Table 1.

General characteristics of people with and without sarcopenia.

| Sarcopeniaa | P‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 54) | No (n = 246) | ||

| Age (year) | 68.50 ± 7.99 | 66.42 ± 7.61 | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.11 ± 2.59 | 28.10 ± 4.15 | < 0.001 |

| Physical activity (MET-h/w) | 19.24 ± 20.47 | 22.08 ± 24.50 | 0.42 |

| Female (%) | 40.7 | 53.3 | 0.09 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 13 | 13.4 | 0.93 |

| Smoking (%) | 14.8 | 12.2 | 0.60 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes (%) | 11 | 23 | 0.06 |

| MI (%) | 13 | 12 | 0.81 |

| CVA (%) | 5.6 | 2.0 | 0.14 |

| Asthma (%) | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.93 |

| Arthritis (%) | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0.91 |

| Drug history | |||

| Sexual hormone use (%) | 5.6 | 2.4 | 0.22 |

| Statin use (%) | 44.4 | 35.0 | 0.19 |

| Corticosteroid use (%) | 5.6 | 2.0 | 0.14 |

All values are mean ± SD, unless indicated. aSarcopenia was defined based on European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition27. ‡ANOVA for continuous variables and Chi-squared test for categorical variables. BMI body mass index, MI myocardial infarction, CVA cerebrovascular accident.

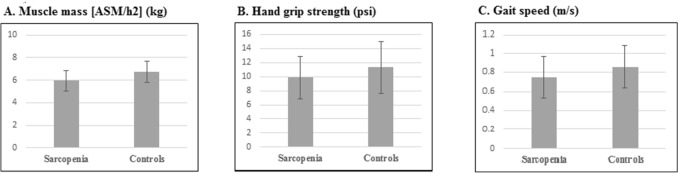

Comparison of cases and controls in terms of components of sarcopenia is shown in Fig. 1. As expected, individuals with sarcopenia had significantly lower mean values of muscle mass (6.75 ± 0.95 vs. 5.95 ± 0.88, P < 0.001, Fig. 1A), hand grip strength (11.30 ± 3.64 vs. 9.85 ± 2.96, P = 0.007, Fig. 1B) and gait speed (0.86 ± 0.22 vs. 0.75 ± 0.22, P = 0.001, Fig. 1B) Fig. 1C, compared with healthy individuals.

Figure 1.

Mean muscle mass, hand grip strength and gait speed between cases and controls. A. Comparison of cases and controls in mean muscle mass, B. Comparison of cases and controls in hand grip strength. C. Comparison of cases and controls in gait speed.

Table 2 indicates comparison of dietary nutrients intakes between sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic subjects. There were no significant differences in terms of energy, total BCAAs, leucine, isoleucine, valine, proteins, carbohydrates, proteins, fats, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxin, folate, B12, biotin, iron, calcium, magnesium, zinc and tryptophan between the two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of dietary intakes of participants with and without sarcopenia.

| Sarcopeniaa | P‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 54) | No (n = 246) | ||

| Energy (kcal/day) | 2323 ± 1331 | 2249 ± 819 | 0.59 |

| Total BCAAs (g/day) | 12.78 ± 5.70 | 12.88 ± 5.08 | 0.90 |

| Leucine (g/day) | 5.48 ± 2.48 | 5.50 ± 2.20 | 0.95 |

| Isoleucine (g/day) | 3.30 ± 1.50 | 3.33 ± 1.27 | 0.86 |

| Valine (g/day) | 3.99 ± 1.72 | 4.04 ± 1.64 | 0.85 |

| Protein (g/day) | 85.5 ± 39.38 | 86.18 ± 30.87 | 0.89 |

| Fat (g/day) | 58.94 ± 43.08 | 59.36 ± 24.49 | 0.47 |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) | 381 ± 242 | 363 ± 159 | 0.92 |

| Dietary fiber (g/day) | 29.10 ± 15.54 | 30.18 ± 13.94 | 0.61 |

| Thiamin (mg/day) | 2.29 ± 1.19 | 2.21 ± 0.95 | 0.59 |

| Riboflavin (mg/day) | 2.32 ± 0.95 | 2.40 ± 0.90 | 0.60 |

| Niacin (mg/day) | 21.27 ± 4.03 | 21.06 ± 7.55 | 0.90 |

| Pantothenic acid (mg/day) | 7.43 ± 2.62 | 7.85 ± 2.91 | 0.33 |

| Pyridoxin (mg/day) | 2.90 ± 3.45 | 2.54 ± 1.05 | 0.16 |

| Folate (μg/day) | 515 ± 228 | 550 ± 182 | 0.22 |

| Cobalamin (μg/day) | 4.49 ± 2.42 | 4.57 ± 2.67 | 0.83 |

| Biotin(μg/day) | 23.75 ± 9.82 | 24.08 ± 14.52 | 0.87 |

| Fe (mg/day) | 20.48 ± 11.80 | 19.93 ± 6.95 | 0.65 |

| Ca (mg/day) | 1308 ± 555 | 1346 ± 583 | 0.66 |

| Zn (mg/day) | 12.28 ± 6.44 | 12.30 ± 4.40 | 0.97 |

| Magnesium (mg/day) | 449 ± 305 | 438 ± 144 | 0.68 |

| Tryptophan (mg/day) | 724 ± 349 | 729 ± 259 | 0.90 |

All values are mean ± SD; energy intake is adjusted for age and sex, all other values are adjusted for age, sex and energy intake. aSarcopenia was defined based on European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition27. ‡ANOVA for all variables. BCAAs branched-chain amino acids.

General characteristics of study population across tertiles of total and individual BCAAs are summarized Table 3. Patients in the top tertile of leucine intake were more likely to be younger than those in the lowest tertile (P = 0.01). Moreover, participants in the third tertile of isoleucine intake were more physically active than those in the first tertile (P = 0.03). No other significant differences were found comparing extreme tertiles of total and individual BCAAs intake.

Table 3.

General characteristics of study participants across tertile categories of BCAAs.

| BCAAs | P† | Valine | P† | Leucine | P† | Isoleucine | P† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 96) | T1 (n = 106) | T3 (n = 95) | T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 96) | T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 97) | |||||

| Age (year) | 67.04 ± 7.76 | 65.42 ± 7.64 | 0.08 | 66.75 ± 7.76 | 66.55 ± 7.72 | 0.08 | 66.77 ± 7.63 | 65.21 ± 7.64 | 0.01 | 67.38 ± 8.02 | 65.36 ± 7.79 | 0.08 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.55 ± 3.89 | 27.40 ± 4.33 | 0.81 | 27.65 ± 4.30 | 27.65 ± 4.32 | 0.28 | 27.49 ± 3.87 | 27.55 ± 4.72 | 0.72 | 27.43 ± 3.86 | 27.64 ± 4.82 | 0.62 |

| Physical activity (MET-h/w) | 17.95 ± 17.05 | 25.26 ± 25.45 | 0.09 | 118.21 ± 17.01 | 24.80 ± 24.13 | 0.14 | 18.15 ± 67.86 | 25.60 ± 25.38 | 0.08 | 17.61 ± 17.11 | 26.20 ± 25.71 | 0.03 |

| Female (%) | 53.3 | 44.8 | 0.33 | 53.8 | 48.4 | 0.74 | 53.3 | 44.8 | 0.33 | 54.3 | 46.4 | 0.51 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 11.4 | 17.7 | 0.31 | 11.3 | 15.8 | 0.64 | 11.4 | 17.7 | 0.31 | 10.5 | 16.5 | 0.45 |

| Smoking (%) | 13.3 | 14.6 | 0.62 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 0.85 | 13.3 | 14.6 | 0.62 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 0.97 |

| Medical history | ||||||||||||

| Diabetes (%) | 40.3 | 30.6 | 0.59 | 38.7 | 27.4 | 0.69 | 41.9 | 30.6 | 0.39 | 43.5 | 29 | 0.27 |

| MI (%) | 33.3 | 25 | 0.45 | 30.6 | 27.8 | 0.49 | 30.6 | 25 | 0.28 | 30.6 | 27.8 | 0.47 |

| CVA (%) | 50 | 25 | 0.66 | 50 | 12.5 | 0.47 | 50 | 25 | 0.66 | 62.5 | 25 | 0.23 |

| Asthma (%) | 33.3 | 33.3 | 0.99 | 16.7 | 50 | 0.53 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 0.99 | 33.3 | 50 | 0.58 |

| Arthritis (%) | 20 | 60 | 0.40 | 20 | 40 | 0.76 | 20 | 60 | 0.40 | 20 | 60 | 0.41 |

| Drug history | ||||||||||||

| Sexual hormone use (%) | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.66 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 0.66 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.66 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.66 |

| Statin use (%) | 40 | 31.3 | 0.39 | 39.6 | 32.6 | 0.58 | 39 | 31.3 | 0.40 | 40 | 32 | 0.47 |

| Corticosteroid use (%) | 2.9 | 4.2 | 0.38 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 0.38 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 0.38 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 0.40 |

All values are mean ± SD, unless indicated; †ANOVA for continuous variables and Chi-squared test for categorical variables.

BCAAs branched-chain amino acids, BMI Body mass index.

Dietary and nutrient intakes of study population across tertiles categories of exposure variables are displayed in Table 4. Compared to those in the bottom tertile, individuals in the top tertile of both total and individual BCAAs intake had significantly higher intakes of energy, carbohydrates, proteins, fats, dietary fiber, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxin, folate, B12, biotin, iron, calcium, magnesium, zinc and tryptophan (P < 0.001 for all).

Table 4.

Dietary intakes of study participants across categories of BCAAs, valine, leucine and isoleucine intake.

| Variables | BCAAs intake | P† | Valine intake | P† | Leucine intake | P† | Isoleucine intake | P† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 96) | T1 (n = 106) | T3 (n = 95) | T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 96) | T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 97) | |||||

| Energy (kcal/day) | 1722. ± 388 | 2915 ± 1236 | < 0.001 | 1718 ± 387 | 2889 ± 1250 | < 0.001 | 1726 ± 394 | 2906 ± 1238 | < 0.001 | 1717 ± 386 | 2838 ± 1111 | < 0.001 |

| Protein (g/day) | 59.93 ± 10.21 | 117.33 ± 35.75 | < 0.001 | 60.41 ± 10.91 | 117.08 ± 36.26 | < 0.001 | 60.42 ± 11.50 | 117.20 ± 35.80 | < 0.001 | 59.80 ± 10.09 | 116.51 ± 35.79 | < 0.001 |

| Fat (g/day) | 45.38 ± 13.90 | 75.91 ± 30.56 | < 0.001 | 45.20 ± 13.95 | 74.02 ± 30.51 | < 0.001 | 45.20 ± 13.94 | 75.72 ± 30.72 | < 0.001 | 45.19 ± 13.89 | 75.53 ± 30.76 | < 0.001 |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) | 284 ± 78.95 | 465 ± 255 | < 0.001 | 283 ± 78.78 | 463 ± 258 | < 0.001 | 285 ± 79.74 | 483 ± 255 | < 0.001 | 283 ± 78.74 | 445 ± 202 | < 0.001 |

| Dietary fiber (g/day) | 23.49 ± 7.12 | 37.32 ± 19.32 | < 0.001 | 23.62 ± 7.36 | 37.31 ± 19.83 | < 0.001 | 23.71 ± 7.44 | 37.44 ± 19.33 | < 0.001 | 23.53 ± 7.10 | 35.99 ± 13.43 | < 0.001 |

| Thiamin (mg/day) | 1.67 ± 0.45 | 2.86 ± 1.24 | < 0.001 | 1.67 ± 0.45 | 2.85 ± 1.26 | < 0.001 | 1.68 ± 0.46 | 2.85 ± 1.24 | < 0.001 | 1.66 ± 0.45 | 2.75 ± 0.98 | < 0.001 |

| Riboflavin (mg/day) | 1.65 ± 0.29 | 3.25 ± 0.98 | < 0.001 | 1.66 ± 0.29 | 3.27 ± 0.98 | < 0.001 | 1.67 ± 0.36 | 3.24 ± 0.98 | < 0.001 | 1.66 ± 0.29 | 3.18 ± 0.90 | < 0.001 |

| Niacin (mg/day) | 16.38 ± 3.98 | 26.46 ± 9.63 | < 0.001 | 16.38 ± 4.03 | 26.15 ± 9.79 | < 0.001 | 16.49 ± 4.07 | 26.37 ± 9.64 | < 0.001 | 16.27 ± 3.99 | 26.20 ± 9.40 | < 0.001 |

| Pantothenic acid (mg/day) | 5.59 ± 1.15 | 10.38 ± 3.14 | < 0.001 | 5.59 ± 1.15 | 10.45 ± 3.13 | < 0.001 | 5.65 ± 1.28 | 10.35 ± 3.15 | < 0.001 | 5.60 ± 1.15 | 10.27 ± 3.20 | < 0.001 |

| Pyridoxin (mg/day) | 1.91 ± 0.50 | 3.22 ± 1.50 | < 0.001 | 1.90 ± 0.50 | 3.21 ± 1.53 | < 0.001 | 1.92 ± 0.53 | 3.21 ± 1.50 | < 0.001 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| Folate (μg/day) | 421 ± 104 | 673 ± 206 | < 0.001 | 421 ± 106 | 671 ± 209 | < 0.001 | 425 ± 110 | 672 ± 206 | < 0.001 | 419 ± 104 | 663 ± 210 | < 0.001 |

| Cobalamin (μg/day) | 2.80 ± 0.93 | 6.85 ± 3.25 | < 0.001 | 2.80 ± 0.95 | 6.91 ± 3.24 | < 0.001 | 2.81 ± 0.97 | 6.83 ± 3.27 | < 0.001 | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 3.2 | < 0.001 |

| Biotin (μg/day) | 17.21 ± 4.83 | 32.15 ± 19.84 | < 0.001 | 17.38 ± 4.99 | 32.40 ± 19.97 | < 0.001 | 17.40 ± 5.21 | 32.15 ± 19.84 | < 0.001 | 17.14 ± 4.77 | 30.10 ± 8.79 | < 0.001 |

| Fe (mg/day) | 15.53 ± 3.79 | 25.27 ± 9.99 | < 0.001 | 15.55 ± 3.91 | 25.04 ± 10.19 | < 0.001 | 15.55 ± 3.82 | 25.32 ± 9.99 | < 0.001 | 15.47 ± 3.80 | 25.00 ± 9.83 | < 0.001 |

| Ca (mg/day) | 893 ± 197 | 1854 ± 626 | < 0.001 | 891 ± 200 | 1883 ± 620 | < 0.001 | 907 ± 248 | 1849 ± 628 | < 0.001 | 902 ± 202 | 1823 ± 642 | < 0.001 |

| Zn (mg/day) | 8.70 ± 1.54 | 16.53 ± 4.96 | < 0.001 | 8.71 ± 1.60 | 16.51 ± 5.00 | < 0.001 | 8.78 ± 1.74 | 16.49 ± 4.97 | < 0.001 | 8.69 ± 1.53 | 16.39 ± 5.02 | < 0.001 |

| Magnesium (mg/day) | 322 ± 73.16 | 568 ± 187 | < 0.001 | 324 ± 76.27 | 565 ± 189 | < 0.001 | 324 ± 77.17 | 568 ± 187 | < 0.001 | 322 ± 72.77 | 560 ± 185 | < 0.001 |

| Tryptophan (mg/day) | 497 ± 85.11 | 1009 ± 297 | < 0.001 | 504.69 ± 97.50 | 1002 ± 305 | < 0.001 | 500 ± 92.25 | 1012 ± 294 | < 0.001 | 494 ± 80.66 | 1014 ± 290 | < 0.001 |

All values are mean ± SD; †ANOVA for all variables.

The prevalence of sarcopenia and its components across tertile categories of BCAAS, valine, leucin and isoleucine intakes are showed in Fig. 2. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its components were not significantly different across tertile categories of total and individual BCAAs intake.

Figure 2.

The prevalence of sarcopenia and its components across tertile categories of BCAAS, valine, leucin and isoleucine intakes. A) The prevalence of sarcopenia and its components across tertile categories of BCAAS intake, B) The prevalence of sarcopenia and its components across tertile categories of valine intakes, C) The prevalence of sarcopenia and its components across tertile categories of leucin intake, D) The prevalence of sarcopenia and its components across tertile categories isoleucine intake.

Comparing means of muscle mass (kg), hand grip strength (psi), and gait speed (m/s) across tertile categories of total and individual BCAAs, we failed to find any significant differences (Table 5).

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted means of components of sarcopenia across tertiles of total and individual BCAAs intake.

| Variables | BCAAs intake | P† | Valine intake | P† | Leucine intake | P† | Isoleucine intake | P† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 96) | T1 (n = 106) | T3 (n = 95) | T1 (n = 105) | T3 (n = 96) | T1 (n = 106) | T3 (n = 95) | |||||

| Muscle mass [ASM/h2] (kg) | ||||||||||||

| Crude | 6.53 ± 0.09 | 6.70 ± 0.09 | 0.48 | 6.56 ± 0.10 | 6.67 ± 0.09 | 0.72 | 6.53 ± 0.09 | 6.73 ± 0.10 | 0.32 | 6.54 ± 0.09 | 6.71 ± 0.09 | 0.44 |

| Modela | 6.56 ± 0.08 | 6.62 ± 0.09 | 0.77 | 6.58 ± 0.08 | 6.63 ± 0.09 | 0.94 | 6.55 ± 0.08 | 6.65 ± 0.09 | 0.73 | 6.58 ± 0.08 | 6.64 ± 0.09 | 0.88 |

| Hand grip strength (psi) | ||||||||||||

| Crude | 10.79 ± 0.34 | 11.78 ± 0.38 | 0.04 | 10.74 ± 0.34 | 11.48 ± 0.38 | 0.31 | 10.80 ± 0.34 | 11.7 ± 0.39 | 0.05 | 10.77 ± 0.34 | 11.65 ± 3.84 | 0.12 |

| Modela | 10.84 ± 0.24 | 11.39 ± 0.26 | 0.30 | 10.79 ± 0.24 | 11.28 ± 0.26 | 0.44 | 10.83 ± 0.24 | 11.34 ± 0.26 | 0.42 | 10.95 ± 0.24 | 11.29 ± 0.26 | 0.51 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | ||||||||||||

| Crude | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.84 ± 0.21 | 0.85 ± 0.21 | 0.81 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.53 |

| Modela | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.95 |

Obtained from ANOVA (P < 0.05 significant).

Modela: Adjusted for energy, age and sex.

Findings from linear regression analysis of the association between BCAAs and components of sarcopenia revealed no significant association between BCAAs intake and components of sarcopenia (data not shown).

Crude and multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for sarcopenia and its components by tertiles of BCAAs intake are indicated in Table 6. In the crude model, no significant associations were seen between total BCAAs intake and odds of sarcopenia (OR for comparison of extreme tertiles 0.48, 95% CI 0.19–1.19, P-trend = 0.10) and its components (For muscle mass 0.83, 95% CI 0.39–1.77, P-trend = 0.63; for hand grip strength 0.81, 95% CI 0.37–1.75, P-trend: 0.59; for gait speed 1.22, 95% CI 0.58–2.57, P-trend = 0.56). After adjusting for some potential confounders including age, sex and energy intake, this non-significant relationship did not alter. Further adjustment for other potential confounders did not affect the findings.

Table 6.

Crude and multivariable-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for sarcopenia and its components across tertiles of BCAAs intake.

| Tertiles of BCAAs intake | P trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Sarcopenia | ||||

| n (case) | 105 | 99 | 96 | |

| Crude | 1 | 0.73(0.36–1.48) | 0.60(0.29–1.26) | 0.17 |

| Model 1a | 1 | 0.65(0.31–1.35) | 0.47(0.19–1.13) | 0.08 |

| Model 2b | 1 | 0.66(0.31–1.38) | 0.48(0.19–1.19) | 0.10 |

| Lower muscle massc | ||||

| Crude | 1 | 0.89(0.51–1.57) | 0.86(0.49–1.52) | 0.61 |

| Model 1a | 1 | 1.21(0.58–2.50) | 1.05(0.548–2.06) | 0.59 |

| Model 2b | 1 | 0.90(0.47–1.70) | 0.83(0.39–1.77) | 0.63 |

| Lower hand grip strengthd | ||||

| Crude | 1 | 0.91(0.50–1.64) | 0.90(0.50–1.64) | 0.74 |

| Model 1a | 1 | 0.88(0.46–1.68) | 0.88(0.41–1.87) | 0.73 |

| Model 2b | 1 | 0.89(0.45–1.75) | 0.81(0.37–1.75) | 0.59 |

| Lower gait speede | ||||

| Crude | 1 | 1.15(0.66–2.0) | 0.82(0.46–1.46) | 0.53 |

| Model 1a | 1 | 1.14(0.62–1.14) | 1.06(0.52–2.14) | 0.84 |

| Model 2b | 1 | 1.23(0.6–2.30) | 1.22(0.58–2.57) | 0.56 |

Data are OR (95% CI).

aModel 1: Adjusted for age, sex and energy intake. bModel 2: Further adjusted for physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, medication use (statin, corticosteroid, estrogen, testosterone), and positive history of disease. cMuscle mass lower than 5.5 (kg/m2) for women and 7.0 (kg/m2) for men27. dLower muscle strength was defined according previous study32. eGait speeds equal or slower than 0.8 m/s27.

Crude and multivariable-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for sarcopenia and its components by tertiles of valine, leucine and isoleucine intake are shown in Table 7. Similar to total BCAAs intake, we did not find any significant association between individual BCAAs intake and odds of sarcopenia or its components. This was the case when all potential confounders were taken into account.

Table 7.

Crude and multivariable-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for sarcopenia and its components across categories of valine, leucine and isoleucine intake.

| Tertile of valine | P† | Tertile of leucine | P† | Tertile of isoleucine | P† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | ||||

| n (case) | 105 | 99 | 96 | 106 | 99 | 95 | 105 | 99 | 96 | |||

| Sarcopenia | ||||||||||||

| Crude | 1 | 0.65(0.32–1.32) | 0.59(0.28–1.22) | 0.14 | 1 | 0.73(0.36–1.48) | 0.60(0.29–1.26) | 0.17 | 1 | 0.69(0.34–1.41) | 0.65(0.31–1.33) | 0.23 |

| Model 1† | 1 | 0.55(0.26–1.16) | 0.46(0.19–1.09) | 0.06 | 1 | 0.63(0.30–1.32) | 0.47(0.19–1.13) | 0.08 | 1 | 1.82(0.79–4.18) | 1.12(0.50–2.52) | 0.14 |

| Model 2‡ | 1 | 0.55(0.26–1.17) | 0.46(0.18–1.13) | 0.07 | 1 | 0.63(0.30–1.33) | 0.48(0.19–1.18) | 0.09 | 1 | 0.61(0.28–1.31) | 0.57(0.24–1.34) | 0.18 |

| Lower muscle mass | ||||||||||||

| Crude | 1 | 0.91(0.52–1.60) | 0.78(0.44–1.38) | 0.40 | 1 | 0.97(0.55–1.70) | 0.90(0.51–1.58) | 0.71 | 1 | 0.99(0.56–1.74) | 0.88(0.50–1.56) | 0.67 |

| Model 1† | 1 | 0.81(0.43–1.51) | 0.72(0.35–1.49) | 0.38 | 1 | 0.93(0.50–1.74) | 0.86(0.42–1.77) | 0.68 | 1 | 0.96(0.51–1.80) | 0.87(0.43–1.76) | 0.70 |

| Model 2‡ | 1 | 1.31(0.62–2.75) | 1.04(0.52–2.05) | 0.46 | 1 | 0.96(0.51–1.83) | 0.89(0.42–1.87) | 0.76 | 1 | 0.96(0.50–1.83) | 0.91(0.43–1.88) | 0.80 |

| Lower hand grip strength | ||||||||||||

| Crude | 1 | 0.73(0.40–1.33) | 0.90(0.50–1.62) | 0.70 | 1 | 0.87(0.48–1.56) | 0.95(0.52–1.72) | 0.86 | 1 | 1.00(0.55–1.82) | 1.07(0.59–1.93) | 0.81 |

| Model 1† | 1 | 0.75(0.39–1.44) | 0.84(0.40–1.76) | 0.62 | 1 | 0.86(0.45–1.66) | 0.95(0.45–2.00) | 0.88 | 1 | 1.03(0.53–1.99) | 1.09(0.52–2.28) | 0.80 |

| Model 2‡ | 1 | 0.77(0.39–1.52) | 0.77(0.36–1.66) | 0.50 | 1 | 0.87(0.44–1.70) | 0.88(0.41–1.89) | 0.73 | 1 | 0.95(0.44–2.05) | 1.02(0.51–2.04) | 0.90 |

| Lower gait speed | ||||||||||||

| Crude | 1 | 1.08(0.62–1.88) | 0.82(0.46–1.45) | 0.51 | 1 | 1.06(0.61–1.85) | 0.79(0.45–1.40) | 0.44 | 1 | 0.84(0.48–1.48) | 0.79(0.45–1.38) | 0.41 |

| Model 1† | 1 | 1.06(0.58–1.94) | 0.97(0.48–1.95) | 0.95 | 1 | 0.99(0.54–1.80) | 0.99(0.49–2.01) | 0.99 | 1 | 0.87(0.47–1.60) | 1.01(0.51–2.01) | 0.97 |

| Model 2‡ | 1 | 1.14(0.61–2.13) | 1.09(0.52–2.27) | 0.79 | 1 | 1.03(0.55–1.92) | 1.15(0.55–2.40) | 0.71 | 1 | 0.94(0.50–1.77) | 1.21(0.59–2.49) | 0.61 |

Data are OR (95% CI).

†Model 1: Adjusted for age, sex and energy intake. ‡Model 2: Further adjusted for physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, medication use (statin, corticosteroid, estrogen, testosterone), and positive history of disease. †Muscle mass lower than 5.5 (kg/m2) for women and 7.0 (kg/m2) for men27. ‡Lower muscle strength was defined according previous study32. §Gait speeds equal or slower than 0.8 m/s27.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study among 300 adults including 150 men and 150 women, we failed to find any significant association between dietary intakes of total and individual BCAAs and odds of sarcopenia. The results remained non-significant even after controlling for several potential confounders. To our knowledge, the current investigation is the first reporting the association between dietary intakes of BCAAs and risk of sarcopenia.

In recent decades, sarcopenia, defined as the gradual decline in skeletal muscle mass and function with age, has become a global public health issue as the population ages34–36. The prevalence of sarcopenia in developing countries such as the Middle East is higher than that in developed countries7, 37, which may be due to the differences in dietary patterns and other non-genetic factors24, 38. Numerous studies have explored the role of diet in the prevention of this condition39–41. Most have highlighted the role of protein intakes. Proteins can stimulate and regulate muscle protein anabolism, albeit in the presence of BCAAs15, 42. In the current study, we failed to find any significant relationship between dietary intakes of total and individual BCAAs and odds of sarcopenia or its components. In a cross-sectional study, plasma concentrations of leucine, isoleucine and valine in sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic individuals were not significantly different43. In addition, in the BIOSPHERE study on 68 community dwelling subjects aged 70 and over, individuals with physical disabilities and sarcopenia, as defined by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health criteria (FNIH), had no significant difference with those who were robust in terms of circulating BCAAs levels44. In contrast, in a cross-sectional study, it was found that reduced concentrations of BCAAs were associated with sarcopenia and its components; such that participants in the lowest quartile of BCAA concentrations, whom mean BCAA levels were 453 µmol/L, had a worse sarcopenic indices than those in the highest quartile with a mean serum concentrations of 571 µmol/L16. Ottado et al. showed that mean plasma levels of non-fasting BCAAs, valine, leucine and isoleucine in patients with sarcopenia (0.28, 0.16, 0.06 and 0.05 mmol/L, respectively) were lower than those in healthy individuals (0.31, 0.17, 0.07 and 0.06 mmol/L, respectively)17. However, they did not consider the protein content of the last meal before blood sampling which might affect their findings45. Some studies have shown that there is no significant agreement between dietary intakes and plasma BCAA levels46. Others have examined the effect of BCAAs supplementation on muscle health and strength. Hung-Ko et al. conducted a clinical trial to investigate the effect of BCAAs supplementation on 33 sarcopenic and pre-sarcopenic individuals and found that supplementation for five weeks in both groups improved muscle performance including skeletal mass index, gait speed and muscle strength, but these positive effects were lost after a few months18. Another study on older malnourished participants reported that a mixture of amino acids including BCAAs for two months improved muscle mass and performance in this population47. Overall, based on earlier findings and considering the current study, it seems that BCAAs might have a beneficial effect on muscle strength in a short term but their contribution to sarcopenia and maintaining muscle performance in long term is still questionable. Currently, there is no information about the optimum plasma BCAA levels to prevent sarcopenia. Further studies are needed to examine the optimal plasma levels of BCAA to prevent muscle loss as well as the minimum threshold concentrations of these amino acids required to prevent excessive muscle loss.

Lack of a clear link between dietary intakes of BCAAs and odds of sarcopenia in the current study might be partly explained by the small number of patients with sarcopenia; such that when we categorized study participants based on tertiles of BCAAs intake, we had only 14 individuals with sarcopenia in the highest tertile. Such a small population of sarcopenic patients in the top category resulted in a wide range of confidence intervals forcing the association toward null. Further, in this study, a squeeze bulb dynamometer was used to evaluate and grip strength instead of the gold standard, the Jamar handheld dynamometer42, which might have led to misdiagnosis of sarcopenia in some participants.

While we did not find any association between BCAAs intake and sarcopenia, some possible mechanisms may help explaining our hypothesis about existence of the association between BCAAs intake and muscle health and performance. BCAAs especially leucine, have specific positive effects on signaling pathways for muscle protein anabolism by activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and the downstream phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase (p70S6k) and 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and relevant signaling pathways18, 48. BCAAs also decrease muscle protein breakdown by mTOR signaling pathway49. However, some studies have shown a potential link between BCAAs and the development of insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes50–52. In animal models, decreasing dietary BCAAs resulted in increased energy expenditure and decreased insulin resistance53. In fact, BCAAs reduce FEGF-21 by altering fat metabolism and have an adverse effect on insulin sensitivity. Insulin resistance, through the mTor pathway, might affect proteolysis and reduce predominantly oxidative type I fibers that can further decrease glycolytic type II fibers and affect muscle health53–55. Therefore, given a positive link between BCAAs and insulin resistance on one hand and the link between insulin resistance and sarcopenia55 on the other hand, lack of finding a significant association in the current study might be explained by this mechanism.

The major strengths of the current study are using a reproducible and valid FFQ for assessment of usual dietary intakes, considering several potential confounders in the analysis and being the first study on dietary intakes of BCAAs and sarcopenia. Our investigation had also some limitations. First, lack of data on plasma levels of BCAAs might limit the interpretability of our findings. Second, the sarcopenic individuals in the study might have changed their dietary intakes after observing reduced muscle strength and muscle mass, which the cross-sectional nature of the study did not let us to know these changes. Third, although the dietary evaluation was done by a validated FFQ, these measurements have always measurement errors which might further affect our findings. Finally, due to financial constraints and low access to the only DEXA device available in Tehran (maximum 300 cases), the sample size was small and sampling was limited to the area where the device was located.

In conclusion, we found no significant association between dietary intakes of total and individual BCAAs and odds of sarcopenia and its components after adjusting for potential confounders in this cross-sectional study among Iranian adults. Additional studies, especially with a larger sample size and prospective design, are required to further examine the association between dietary intakes of BCAAs and sarcopenia.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all persons who kindly participated in the study.

Abbreviations

- BCAAs

Branched-chain amino acids

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- SD

Standard deviation

- FFQ

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- IPAQ

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- MET-h/week

Metabolic equivalents-hours per week

- BMI

Body mass index

- SFA

Saturated fatty acid

- MUFAs

Mono-unsaturated fatty acids

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- EWGSOP

European Working Group on Sarcopenia

- ASM

Appendicular skeletal muscle

- PSI

Pound per square inch

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

Author contributions

S.E.M., R.H., A.B., R.H., A.D.M. and A.E. contributed to the conception, design, data collection, statistical analyses, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, approval of the final version of the manuscript and agreed for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The financial support for this study comes from the Tehran Endocrine and Metabolism Research Center and the Tehran University of Medical Science.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Sara Ebrahimi-Mousavi and Rezvan Hashemi.

References

- 1.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Low relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002;50:889–896. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzoli R, et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013;93:101–120. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9758-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang SF, Lin PL. Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the association of sarcopenia with mortality. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016;13:153–162. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shafiee G, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis of general population studies. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2017;16:21. doi: 10.1186/s40200-017-0302-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher D, et al. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass: Effects of age, gender, and ethnicity. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997;83:229–239. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: A systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS) Age Ageing. 2014;43:748–759. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L-K, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: Consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014;15:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004;52:80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamel HK, Maas D, Duthie EH. Role of hormones in the pathogenesis and management of sarcopenia. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:865–877. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan L-J, Liu S-L, Lei S-F, Papasian CJ, Deng H-W. Molecular genetic studies of gene identification for sarcopenia. Hum. Genet. 2012;131:1–31. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillard F, et al. Physical activity and sarcopenia. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2011;27:449–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beasley JM, Shikany JM, Thomson CA. The role of dietary protein intake in the prevention of sarcopenia of aging. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2013;28:684–690. doi: 10.1177/0884533613507607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volpi E, Kobayashi H, Sheffield-Moore M, Mittendorfer B, Wolfe RR. Essential amino acids are primarily responsible for the amino acid stimulation of muscle protein anabolism in healthy elderly adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78:250–258. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker DK, et al. Exercise, amino acids and aging in the control of human muscle protein synthesis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011;43:2249. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318223b037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis. J. Nutr. 2006;136:227S–231S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.227S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ter Borg S, et al. Low levels of branched chain amino acids, eicosapentaenoic acid and micronutrients are associated with low muscle mass, strength and function in community-dwelling older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2019;23:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottestad I, et al. Reduced plasma concentration of branched-chain amino acids in sarcopenic older subjects: A cross-sectional study. Br. J. Nutr. 2018;120:445–453. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko C-H, et al. Effects of enriched branched-chain amino acid supplementation on sarcopenia. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:15091. doi: 10.18632/aging.103576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komar B, Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Effects of leucine-rich protein supplements on anthropometric parameter and muscle strength in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2015;19:437–446. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy CH, et al. Leucine supplementation enhances integrative myofibrillar protein synthesis in free-living older men consuming lower-and higher-protein diets: A parallel-group crossover study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016;104:1594–1606. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.136424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paddon-Jones D, et al. Essential amino acid and carbohydrate supplementation ameliorates muscle protein loss in humans during 28 days bedrest. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:4351–4358. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashemi R, et al. Diet and its relationship to sarcopenia in community dwelling Iranian elderly: A cross sectional study. Nutrition. 2015;31:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arai H, Akishita M, Chen LK. Growing research on sarcopenia in Asia. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2014;14:1–7. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Food intake patterns may explain the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among Iranian women. J. Nutr. 2008;138:1469–1475. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.8.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esmaillzadeh A, et al. Dietary patterns, insulin resistance, and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;85:910–918. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashemi R, et al. Sarcopenia and its determinants among Iranian elderly (SARIR): Study protocol. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2012;11:23. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willett WC, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985;122:51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghaffarpour M, Houshiar-Rad A, Kianfar H. The manual for household measures, cooking yields factors and edible portion of foods. Tehran Nashre Olume Keshavarzy. 1999;7:213. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haytowitz, D. et al.USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 24. (US Department of Agriculture, 2011).

- 31.Heymsfield SB, et al. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass: Measurement by dual-photon absorptiometry. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990;52:214–218. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merkies I, et al. Assessing grip strength in healthy individuals and patients with immune-mediated polyneuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1393–1401. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200009)23:9<1393::aid-mus10>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirmiran P, Esfahani FH, Mehrabi Y, Hedayati M, Azizi F. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:654–662. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beaudart C, Rizzoli R, Bruyère O, Reginster J-Y, Biver E. Sarcopenia: Burden and challenges for public health. Arch. Public Health. 2014;72:45. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dodds RM, Roberts HC, Cooper C, Sayer AA. The epidemiology of sarcopenia. J. Clin. Densitom. 2015;18:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao L, Morley JE. Sarcopenia is recognized as an independent condition by an international classification of disease, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM) code. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016;17:675–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashemi R, et al. Sarcopenia and its associated factors in Iranian older individuals: Results of SARIR study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016;66:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rush EC, Freitas I, Plank LD. Body size, body composition and fat distribution: Comparative analysis of European, Maori, Pacific Island and Asian Indian adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2009;102:632–641. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508207221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanai H. Nutrition for sarcopenia. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2015;7:926. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2361w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson SM, et al. Does nutrition play a role in the prevention and management of sarcopenia? Clin. Nutr. 2018;37:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morley JE, et al. Nutritional recommendations for the management of sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2010;11:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts HC, et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: Towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing. 2011;40:423–429. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toyoshima K, et al. Increased plasma proline concentrations are associated with sarcopenia in the elderly. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calvani R, et al. A distinct pattern of circulating amino acids characterizes older persons with physical frailty and sarcopenia: Results from the BIOSPHERE study. Nutrients. 2018;10:1691. doi: 10.3390/nu10111691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carayol M, et al. Reliability of serum metabolites over a two-year period: A targeted metabolomic approach in fasting and non-fasting samples from EPIC. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwasaki M, et al. Validity of a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire for assessing amino acid intake in Japan: Comparison with intake from 4-day weighed dietary records and plasma levels. J. Epidemiol. 2016;26:36–44. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20150044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buondonno I, et al. From mitochondria to healthy aging: The role of branched-chain amino acids treatment: MATeR a randomized study. Clin. Nutr. 2020;39:2080–2091. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anthony JC, et al. Leucine stimulates translation initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. J. Nutr. 2000;130:2413–2419. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.10.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pasiakos SM, McClung JP. Supplemental dietary leucine and the skeletal muscle anabolic response to essential amino acids. Nutr. Rev. 2011;69:550–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bloomgarden Z. Diabetes and branched-chain amino acids: What is the link? J. Diabetes. 2018;10:350–352. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng Y, et al. Cumulative consumption of branched-chain amino acids and incidence of type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016;45:1482–1492. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Isanejad M, et al. Branched-chain amino acid, meat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Women’s Health Initiative. Br. J. Nutr. 2017;117:1523–1530. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517001568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cummings NE, et al. Restoration of metabolic health by decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids. J. Physiol. 2018;596:623–645. doi: 10.1113/JP275075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berglund ED, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 controls glycemia via regulation of hepatic glucose flux and insulin sensitivity. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4084–4093. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cleasby ME, Jamieson PM, Atherton PJ. Insulin resistance and sarcopenia: Mechanistic links between common co-morbidities. J. Endocrinol. 2016;229:R67–R81. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]