Abstract

The nitrogen-free diet (NFD) method is widely used to determine the ileal endogenous amino acids (IEAAs) losses in broiler chickens. Starch and dextrose are the main components of NFD, but the effects of their proportion in the NFD on the IEAAs and the digestive physiology of broilers are still unclear. This preliminary study aims to explore the best proportion of glucose and corn starch in NFD to simulate the normal intestinal physiology of broilers, which helps to improve the accuracy of IEAAs determination. For this purpose, 28-day-old broiler chickens were allocated to five treatment groups for a 3-day trial, including a control group and four NFD groups. The ratios of dextrose to corn starch (D/CS) in the four NFD were 1.00, 0.60, 0.33, and 0.14, respectively. Results noted that NFD significantly reduced serum IGF-1, albumin, and uric acid levels compared with the control (P < 0.05), except there was no difference between group D/CS 0.33 and the control for IGF-1. The increased Asp, Thr, Ser, Glu, Gly, Ala, Val, Ile, Leu, His, Tyr, Arg, and Pro contents of IEAAs were detected in broilers fed the NFD with a higher ratio of D/CS (1.00 and 0.60) compared to the lower ratio of D/CS (0.33 and 0.14). Moreover, ileal digestibility of dry matter and activity of digestive enzymes increased as the D/CS elevated (P < 0.001). Further investigation revealed that the number of ileal goblet cells and Mucin-2 expression were higher in the group with D/CS at 1.00 when compared with group D/CS 0.33 and the control (P < 0.05). Microbiota analysis showed that NFD reshaped the gut microbiota, characterized by decreased microbial diversity and lower abundance of Bacteroidetes, and increased Proteobacteria (P < 0.05). Our results indicate that a higher D/CS ratio (1.00 and 0.60) in NFD increases IEAAs by promoting digestive enzymes and mucin secretion. However, the excessive proportion of starch (D/CS = 0.14) in NFD was unsuitable for the chicken to digest. The chickens fed with NFD with the D/CS ratio at 0.33 were closer to the normal digestive physiological state. Thus, the ratio of D/CS in NFD at 0.33 is more appropriate to detect IEAAs of broiler chickens.

Subject terms: Zoology, Gastrointestinal system

Introduction

Determination of amino acid (AA) digestibility of raw materials is the critical foundation of feed formulation in poultry production, contributing to better protein utilization and minimizing nitrogen losses. The apparent ileal amino acid digestibility (AID) is measured based on the net disappearance of ingested dietary amino acid from the proximal digestive tract to the distal ileum1. Dietary formulas based on the AID index have been widely employed in diet formulation. Nevertheless, AID underestimates the actual digestibility of AA in broilers by neglecting the ileal endogenous amino acids (IEAAs) losses, especially for low crude protein (CP) ingredients, such as cereal grains2. The IEAAs are considered an inevitable loss, consisting of salivary and gastric secretions, pancreatic and bile secretions, small intestinal secretions, mucus, sloughed epithelial cells, and microbial protein3,4. The formula based on standardized ileal digestibility (SID) can correct the AID by accounting for IEAAs losses induced by the protein-free ingredients. Undoubtedly, SID reflect the digestibility of feed protein more accurately, thereby measuring IEAAs losses to determine the SID of AA is necessary for accurate diet formulation.

Nitrogen-free diets (NFD) are traditionally used in monogastric animals to calculate SID, where the IEAAs losses are determined by measuring AA excretion in the ileal digesta5. Corn starch and dextrose are the main components of the NFD (approximately 80% of NFD), but the ratio of dextrose to corn starch (D/CS) varies in literature (0.21–3.79)6–9, which may, in turn, affect the flow of IEAAs. Kong et al.10 identified that total IEAAs were significantly higher when dextrose was used as a sole source of energy in NFD than corn starch (17,544 vs. 12,779 mg/kg of dry matter intake). Adedokun et al.11 also found that the IEAAs loss in NFD containing only glucose was significantly higher than that in NFD containing only corn starch (11,080 vs. 6038 mg/kg of dry matter intake). Collectively, varied ratios of corn starch and dextrose significantly altered IEAAs losses, thereby affecting the accuracy of the SID and feed formulation. Nevertheless, the underlying reason of how the content of dextrose and starch in NFD affects IEAA loss has not been clearly identified.

The major factors affecting IEAAs flow include feed intake, mucin turnover rate, gut health status, digestive enzyme secretion, environmental and bacterial influence12, which might be reflected in the changes of digestive physiology status. Taken together, this study suggested that the IEAAs losses evaluated under normal digestive physiology status are the most representative of the actual IEAAs loss, which is also why the chickens fed on corn-soybean meal served as a control group in this study. This preliminary study aims to explore the best proportion of dextrose and corn starch in NFD to simulate the normal intestinal physiology of broilers, which helps to improve the accuracy of IEAAs determination (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Ingredient composition and amino acids levels of NFD and control diets (%).

| Ingredient | D/CS 1.00 | D/CS 0.60 | D/CS 0.33 | D/CS 0.14 | Control1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dextrose | 40.00 | 30.00 | 20.00 | 10.00 | 0.00 |

| Corn starch | 40.00 | 50.00 | 60.00 | 70.00 | 0.00 |

| Zeolite2 | 8.88 | 8.88 | 8.88 | 8.88 | 0.00 |

| Cellulose3 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 |

| Soybean oil | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Limestone | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sodium chloride | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Choline chloride (50%) | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Vitamin premix4 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Trace mineral premix5 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Titanium dioxide | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Corn (7.5% CP) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 54.43 |

| Soybean meal (46% CP) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 38.05 |

| DL-methionine (98%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 |

| L-lysine HCL | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 |

| Analyzed amino acids values (as-fed basis) | |||||

| Aspartic acid | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 2.16 |

| Threonine | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| Serine | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.10 |

| Glutamate | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 3.60 |

| Glycine | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.86 |

| Alanine | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.98 |

| Valine | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.79 |

| Isoleucine | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.80 |

| Leucine | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.60 |

| Tyrosine | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.13 |

| Histidine | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| Lysine | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.28 |

| Arginine | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.38 |

| Proline | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.21 |

1Nutrient level of the control diet: Metabolizable energy 2.95MC/kg, Crude protein 22.50%, Ca 1%, non-phytate phosphorous 0.45%.

2The zeolite (Deheng mineral products Co., Ltd, Shijiazhuang, China) was used as premix carrier in the NFD diets, it contains almost no protein, energy or any other digestible nutrients.

3Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CAS: 9004–32-4, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai China).

4Premix vitamin provides per kg of diet: Vitamin A, 10,800 IU; Vitamin D3, 2160 IU; Vitamin E, 4.6 mg; Vitamin K3, 1.0 mg; Vitamin B1, 0.4 mg; Vitamin B2, 5 mg; Vitamin B12, 6 mg; folic acid, 0.1 mg; niacin, 7 mg; pantothenic acid, 5 mg.

5Trace mineral premix provides per kg of diet: Cu, 6 mg; Zn, 50 mg; Fe, 60 mg; Fe, 0.15 mg; I, 0.35 mg.

Table 2.

Nucleotide sequence of primers for gene expression analysis.

| Target gene | F:forward, R: reverse | Primer sequence (5' → 3') | Accession no. | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | F | TGTTACCAACACCCACACCC | NM_205518 | 110 |

| R | TCCTGAGTCAAGCGCCAAAA | |||

| SGLT-1 | F | CATCTTCCGAGATGCTGTCA | XM_015275173 | 169 |

| R | CAGGTATCCGCACATCACAC | |||

| GLUT-2 | F | CCGCAGAAGGTGATAGAAGC | NM_207178 | 87 |

| R | ATTGTCCCTGGAGGTGTT | |||

| Mucin-2 | F | TCACCCTGCATGGATACTTGCTCA | NM_001318434.1 | 228 |

| R | TGTCCATCTGCCTGAATCACAGGT |

SGLT-1: Na( +)-glucose cotransporter 1;GLUT-2: Glucose transporter type 2.

Results

Serum metabolites

It was found that the serum concentrations of albumin and uric acid were significantly decreased in all NFD groups when compared with the control group (Table 3, P < 0.001). The concentration of IGF-1 was significantly decreased in group D/CS 1.00, group D/CS 0.60, and group D/CS 0.14 when compared to the control (P < 0.05). However, the content of IGF-1was not changed significantly between group D/CS 0.33 and the control. There were no statistical differences in insulin, glucose, glucagon, and TP levels among groups.

Table 3.

The effects of different NFD on serum biochemical parameters of broiler chickens.

| Item | D/CS 1.00 | D/CS 0.60 | D/CS 0.33 | D/CS 0.14 | Control | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 12.59 | 13.59 | 12.19 | 12.58 | 13.20 | 0.930 | 0.548 |

| Insulin (IU/mL) | 5.72 | 6.45 | 7.36 | 6.73 | 6.98 | 0.218 | 0.206 |

| Glucagon (pg/mL) | 159.2 | 151.4 | 156.4 | 143.5 | 133.2 | 5.862 | 0.686 |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | 16.26c | 16.86bc | 19.04ab | 15.47c | 21.04a | 1.019 | 0.008 |

| TP (g/L) | 24.10 | 23.75 | 23.83 | 22.47 | 21.32 | 0.548 | 0.466 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 9.10b | 8.42b | 9.53b | 8.88b | 13.10a | 0.210 | < 0.001 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 143.7b | 134.3b | 154.8b | 130.2b | 254.3a | 7.719 | < 0.001 |

IGF-1: Insulin-like growth factor-1; TP: Total protein.

Values are expressed as the mean and pooled SEM (n = 6 per group). Different superscript letters in the same row mean significant differences (P < 0.05).

IEAAs losses

The results of IEAAs losses indicated that Glu was the most abundant AA in IEAAs flow among all NFD groups, followed by Ser (Table 4). Other AAs present in relatively high concentrations were Thr, Asp, Leu, and His, but ranking differed among groups, indicating the D/CS ratio changed the composition of IEAAs flow to a certain extent. Additionally, a higher ratio of D/CS (1.00 and 0.60) increased the endogenous losses of most AA than that of the lower ratio of D/CS (0.33 and 0.14), including Asp, Thr, Ser, Glu, Gly, Ala, Val, Ile, Leu, His, Tyr, Arg, and Pro (P < 0.05), suggesting that the NFD with higher dextrose content could increase the IEAAs losses of chickens.

Table 4.

The basic IEAAs losses (mg/kg DM intake) in ileum of broiler chickens.

| AA | D/CS 1.00 | D/CS 0.60 | D/CS 0.33 | D/CS 0.14 | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp | 1106a | 1134a | 798.6b | 761.4b | 30.333 | < 0.001 |

| Thr | 1119a | 1030a | 768.2b | 620.0b | 25.183 | < 0.001 |

| Ser | 1223a | 1270a | 930.7b | 826.6b | 33.660 | < 0.001 |

| Glu | 2158a | 2064a | 1447b | 1309b | 69.990 | < 0.001 |

| Gly | 614.3a | 622.3a | 437.9b | 408.6b | 56.650 | < 0.001 |

| Ala | 569.4a | 526.3a | 307.5b | 293.9b | 21.043 | < 0.001 |

| Val | 636.6a | 635.1a | 438.8b | 436.9b | 57.146 | 0.001 |

| Ile | 431.2a | 462.0a | 333.7b | 309.0b | 16.455 | 0.009 |

| Leu | 812.2a | 861.5a | 614.6b | 580.4b | 26.852 | 0.002 |

| Tyr | 479.0a | 491.4a | 342.0b | 330.1b | 14.768 | 0.001 |

| Phe | 455.7ab | 560.7a | 393.4b | 357.6b | 20.619 | 0.013 |

| His | 733.2a | 745.1a | 557.3c | 645.9b | 14.189 | < 0.001 |

| Lys | 596.3 | 580.7 | 427.8 | 411.2 | 49.008 | 0.060 |

| Arg | 558.0a | 549.3a | 379.5b | 323.8b | 59.439 | 0.004 |

| Pro | 690.0a | 656.7a | 459.3b | 476.2b | 30.549 | 0.025 |

Values are expressed as the mean and pooled SEM (n = 6 per group). Different superscript letters in the same row mean significant differences (P < 0.05).

Intestinal morphology and goblet cells abundance

As shown in Table 5, there were no significant differences in the villus height and crypt depth in the duodenum and jejunum among groups. In the ileum, the villus height had an upward trend in NFD groups when compared with the control (0.05 < P < 0.1), but the opposite trend was observed for crypt depth (0.05 < P < 0.1). All NFD groups showed a significant rise in the ileal villus height/crypt depth ratio (V/C) when compared to the control (P < 0.05). Moreover, the number of goblet cells in jejunal and ileal villi of all NFD groups was significantly increased when compared to the control (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

The effects of NFD on intestinal morphology of broiler chickens.

| Item | D/CS 1.00 | D/CS 0.60 | D/CS 0.33 | D/CS 0.14 | Control | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duodenum | |||||||

| Villus height (μm) | 1632 | 1539 | 1550 | 1573 | 1436 | 36.120 | 0.550 |

| Crypt depth (μm) | 154.3 | 166.3 | 158.2 | 168.7 | 174.3 | 3.828 | 0.497 |

| V/C1 | 10.76 | 9.40 | 9.96 | 9.61 | 8.48 | 0.235 | 0.067 |

| Goblet cells/100 μm2 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 0.930 | 0.331 |

| Jejunum | |||||||

| Villus height (μm) | 1124 | 1211 | 1101 | 1189 | 1106 | 25.040 | 0.534 |

| Crypt depth (μm) | 136.0 | 160.0 | 143.8 | 145.8 | 161.3 | 3.712 | 0.268 |

| V/C | 8.50 | 7.91 | 7.78 | 8.34 | 7.02 | 0.187 | 0.152 |

| Goblet cells /100 μm | 11a | 12a | 10a | 10a | 8b | 0.227 | 0.001 |

| Ileum | |||||||

| Villus height(μm) | 661.0 | 800.8 | 647.6 | 684.6 | 644.4 | 19.992 | 0.097 |

| Crypt depth(μm) | 122.6 | 133.3 | 125.3 | 127.7 | 146.9 | 2.500 | 0.077 |

| V/C | 5.46a | 6.06a | 5.26a | 5.47a | 4.47b | 0.112 | 0.008 |

| Goblet cells/100 μm | 11a | 12a | 12a | 13a | 9b | 0.277 | 0.022 |

1 V/C: The ratio of villus height to crypt depth.

2The number of goblet cells were quantified by counting the number of stained goblet cells per 100 μm length of villus, and present as the average number of goblet cells per 8 intestinal villi.

Values are expressed as the mean and pooled SEM (n = 6 per group). Different superscript letters in the same row mean significant differences (P < 0.05).

Digestive enzymes

As shown in Table 6, the maltase activity was significantly higher in both D/CS 1.00 and D/CS 0.60 groups compared to the control (P < 0.05). The α-amylase activity showed a significant decrease in all NFD groups when compared with the control (P < 0.05). However, the activity of lipase and sucrase in group D/CS 1.00 was significantly higher than control group (P < 0.05). Group D/CS 0.60 and group D/CS 0.14 showed higher chymotrypsin activity than the control (P < 0.05). These results indicated that increasing the D/CS ratio to 1.00 leads to a higher activity of lipase, sucrase, and maltase, but the activity of most digestive enzymes can be similar to the control group by decreasing the D/CS ratio to 0.33.

Table 6.

The effects of NFD on the ileal digestive enzyme activity of broiler chickens.

| Item | D/CS 1.00 | D/CS 0.60 | D/CS 0.33 | D/CS 0.14 | Control | SEM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maltase (U/mg prot) | 112.3a | 105.0ab | 87.31abc | 81.01bc | 77.34c | 3.885 | 0.033 |

| Sucrase (U/mg prot) | 52.37a | 23.70bc | 28.00b | 6.69c | 9.98bc | 2.812 | < 0.001 |

| Lipase (U/g prot) | 138.4a | 50.80b | 43.15b | 33.64b | 79.66b | 6.713 | < 0.001 |

| α-amylase (U/mg prot) | 4.32b | 3.45b | 7.18b | 7.30b | 29.35a | 1.138 | < 0.001 |

| Chymotrypsin (U/mg prot) | 13.99b | 45.61a | 21.30ab | 47.36a | 16.98b | 3.885 | 0.029 |

The enzyme activity of maltase and sucrase were detected in the mucous of ileum, and the enzyme activity of lipase, α-amylase, and chymotrypsin were detected in the digesta of ileum. Values are expressed as the mean and pooled SEM (n = 6 per group). Different superscript letters in the same row mean significant differences (P < 0.05).

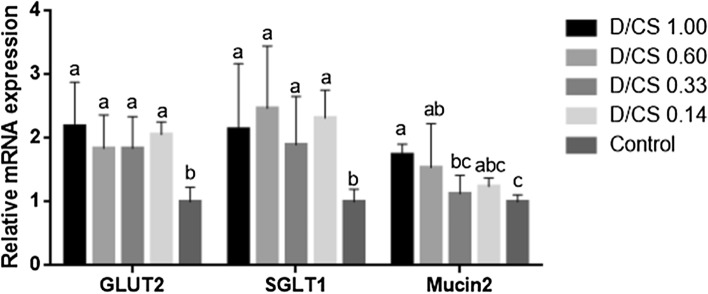

The AID of DM

In addition to increasing enzyme activity, group D/CS 1.00 also showed a significant rise in DM digestibility when compared to the control (Fig. 1, P < 0.05). There was no significant difference among group D/CS 0.60, group D/CS 0.33, and the control group. However, the DM digestibility in group D/CS 0.14 was remarkably lower than that in the control group (P < 0.001), indicating the excess starch is unfavorable for NFD digestion.

Figure 1.

The AID of dry matter in the ileum of broiler chickens (n = 6). Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different, P < 0.05.

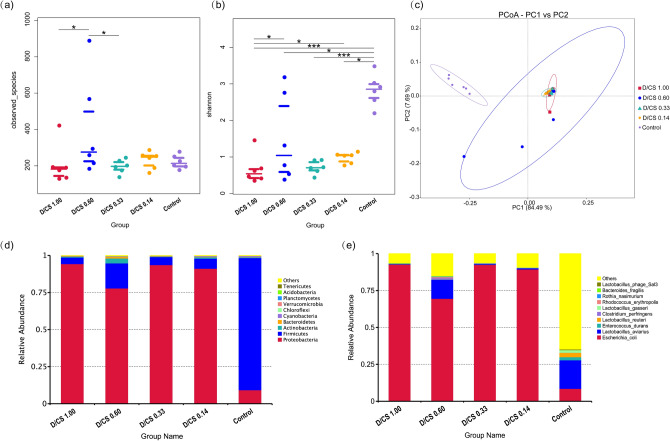

Gene expression

Mucus secreted by goblet cells is an essential component of endogenous amino acids loss. Therefore, the goblet cell marker gene Mucin-2 was detected in this study. As shown in Fig. 2, the relative gene expression of Mucin-2 was significantly higher in the D/CS ratio of 1.00 and 0.60 when compared with the control group (P < 0.05). NFD treatments had an upward expression of mucous glucose transporters, with GLUT-2 and SGLT-1 levels were significantly higher in all NFD groups than in the control group (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

The effects of NFD on the relative gene expression of GLUT-2, SGLT-1 and Mucin-2 (n = 6). Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different, P < 0.05.

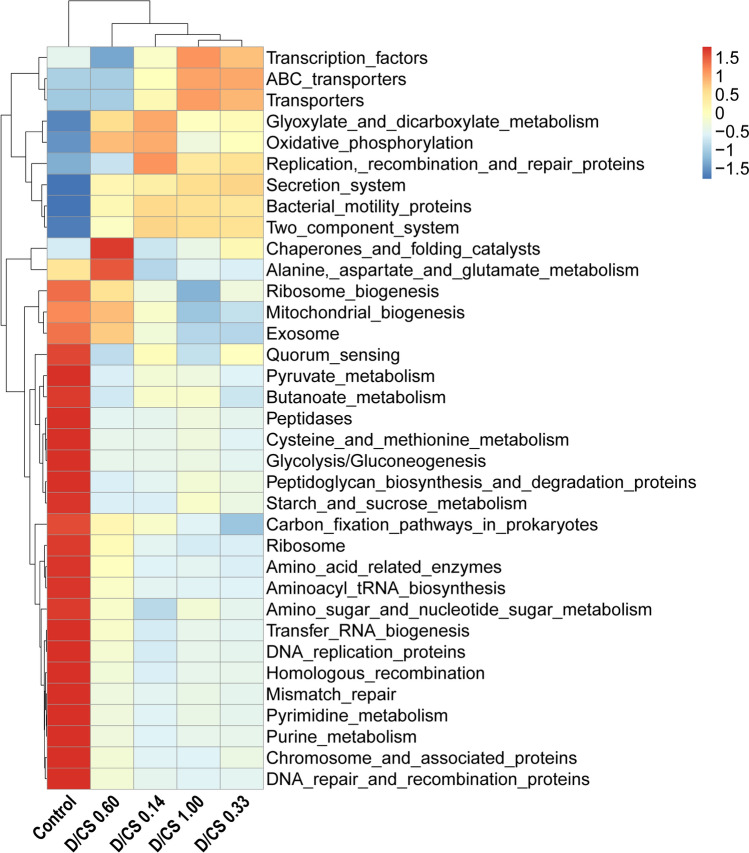

Microflora analysis of ileal digesta

According to the results of 16S sequencing based on operational taxonomic units (OTUs) analysis, the microbiota diversity in the ileum of all NFD treated chickens were reduced markedly at different levels (Fig. 3a, b). The principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the weighted UniFrac distances resulted in significant segregation among groups (Fig. 3c), confirming the presence of compositional microbiota differences in the ileum of NFD treatments and the control. As shown in Fig. 3d, the preponderant bacteria were Proteobacteria (94.29%, 77.87%, 93.63%, 91.18%, respectively) and Firmicutes (4.39%, 16.91%, 5.38%, 6.77%, respectively) in the ileum of four NFD groups at the levels of the phylum. However, Firmicutes (89.11%) was the preponderant bacteria, which was about tenfold higher than Proteobacteria (9.23%) in the control group at the phylum levels. At species level (Fig. 3e), the preponderant bacteria were Escherichia_coli (92.76%, 69.57%, 92.52%, 89.38%, respectively) in the ileum of NFD groups. However, the Lactobacillus_aviarius (19.32%) and Escherichia_coli (8.54%) were the first and second species in ileal microbial communities in the control group, respectively. Considering there were violently disruptive changes of microbiota composition between NFD treatment and the control, it is necessary to analyze the microbial function in this study further. Moreover, the Tax4Fun analysis based on Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) data predicted differentially expressed functional pathways among groups (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

(a) Beeswarm of observed species in the ileal digesta among groups, representing the scatter distribution of the total number of species among different groups. (b) Beeswarm of Shannon index, reflecting the differences of species diversity and evenness among different groups. (c) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the microbial community. The analysis is generally based on the UniFrac distance, each point in the graph represents a sample, the distance between points represents the degree of difference, and the samples of the same group are represented by the same color. (d)The relative abundance of top10 species at phylum level (n = 6). (e) The relative abundance of top10 species at species level (n = 6).

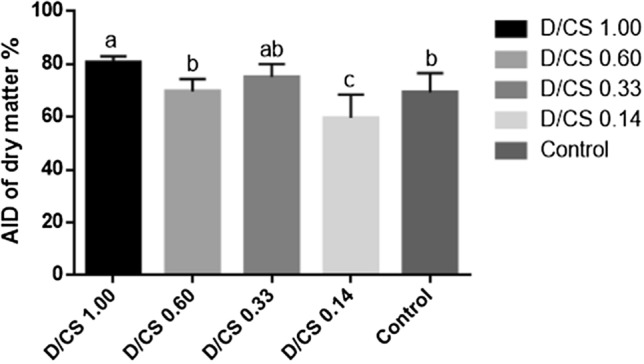

Figure 4.

Cluster analysis of the functional relative abundance of Tax4Fun. According to the functional annotation and abundance information of the samples in the database, the top 35 functions and their abundance information in each sample were selected to draw the thermal map (n = 6).

The four NFD groups harbored very close profiles but differed from those predicted in the control. As shown in Fig. 4, a higher abundance of functions reported for transporters, secretion system, ABC transporters, and two-component system were predicted in NFD groups compared to the control, indicating the microorganism in NFD groups plausibly meets its nutrient requirements for adaption. However, metabolic information related to the DNA repair and recombination protein, the metabolism of amino acids, pyruvate, purine, and pyrimidine appears to be increased in the control group.

Discussion

There are many methods to determine the IEAAs losses in broiler chickens, such as the regression method, the enzymatically hydrolyzed casein method, the NFD method, and the 15N-leucine single-injection method7,13. Among these various methods, the NFD method is most widely used for its simplicity, convenience, and low cost. However, one of the fundamental concerns of NFD is its lack of dietary protein, and the animals can be expected to suffer from malnutrition due to the deficiency of essential amino acids.

This study suggested that the IEAAs losses evaluated under normal digestive physiology status represent the actual IEAAs loss, and chickens offered the control diet represent the normal digestive physiological state. Therefore, some serum biochemical parameters were determined in this study to indicate the basic physiological status and metabolic functions of broiler chickens. We found that the albumin and uric acid levels were decreased in all of the NFD groups as compared with the control, indicating clearly that the protein deficiency led to malnutrition of animals in NFD treatments because low albumin and uric acid levels in serum indicating a poor nutritional status14 and efficiency of protein retention15,16, respectively. Furthermore, serum IGF-1 concentration in these four NFD groups decreased by varying degrees which could reflect some protein restriction because the previous study has shown that serum IGF-1 concentration was reduced in models of severe energy restriction or protein restriction in young growing rats17 . However, the levels of glucose, insulin, and glucagon in serum were not influenced by NDF with different ratios of dextrose to starch, suggesting the normal regulation of blood glucose in NDF treatment.

Although changing the ratio of D/CS in NFD did not alleviate the malnutritions of broiler chickens, it did influence the basic IEAAs of broilers in this study. The most abundant amino acids in the ileal endogenous protein of broilers were Glu, Asp, Thr, Pro, Ser, and Gly18. Previous research showed that the IEAAs flow depends on the ratio of D/CS in NFD, which increased from 12,779 mg/kg to 17,544 mg/kg of DMI as the proportion of corn starch in NFD decreased from 849.1 to 0 g/kg10. Herein, we further narrowed down the ratio of D/CS in the order of 1.00, 0.60, 0.33, and 0.14, and found significant changes when the ratio of D/CS ranged between 0.60 and 0.33, indicating that a higher proportion of dextrose raised ileal IEAAs flow of broiler chickens. These results could be due to the different contributions of sources of endogenous proteins, such as digestive enzyme secretions, mucus, sloughed epithelial cells, and microbial protein.

In the current study, we found that the highest proportion of dextrose (D/CS = 1.00) dramatically increased the activity of lipase, sucrase, and maltase. Excessive digestive enzymes could be reused as either a component of other proteins or recycled after the conservation process19, which might be, in part, result in a high level of IEAAs flow. Glucose absorption was mediated by two kinds of transporters, i.e., co-transportation with sodium ions via SGLT-1 and facilitated diffusion via GLUT-220. In this study, we found that NFD rich in glucose and starch significantly increased the gene expression of these two glucose transporters, indicating that the chickens adapted to the absorption of high carbohydrates in NFD. Notably, the digestive enzymatic activity of group D/CS 0.33 resembled closely with the control group, suggesting that the D/CS at 0.33 was potentially appropriate. However, the digestibility of DM significantly dropped when the D/CS ratio was 0.15, which established its unsuitability for the chicken to digest NFD.

In addition to digestive enzymes, mucins also contribute to the IEAAs loss. The mucus secreted from goblet cells constitutes the interface between the gut lumen and the gut epithelium, which is poorly digested in the small intestine21. We observed no significant difference in villus height and crypt depth among the treatment groups, but the number of goblet cells was increased on the villus of jejunum and ileum in NFD treatment groups. Moreover, the gene expression of ileal Mucin-2 was significantly higher in NFD with D/CS at 1.00 at 0.60 than in control. Dietary composition influences the differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells; for instance, diets rich in carbohydrates or AAs lead to different cell differentiation patterns22. The nourishment of goblet cells to form mucin depends mainly on the absorbed glutamine and glucose, which is easily provided by the prolamines and starch in grain23. Previous in vivo studies indicated that feeding starch increased mucus production in pigs and rats24,25. As NFD is rich in starch and dextrose, these results potentially indicate that NFD could promote mucin secretion by increasing the number of goblet cells.

Apart from mucins, microbial protein in the gut also contributes to IEAAs. A high-glucose diet has been linked to gut microbial diversity losses where the proportion of Bacteroidetes decreased, while the proportion of Proteobacteria was markedly increased26. Consistently, in this study, NFD groups with high sugar directly modulate the gut microbiota, characterized by a lower level of Bacteroidetes and a higher level of Proteobacteria. Since Proteobacteria with adherent and invasive properties are considered to be a rich source of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease and metabolic syndrome27,28, we speculate that gut microbiome may be one variable influencing nutrition metabolism function for animals. Therefore, we used Tax4Fun to predict the functional profile of a microbial community and found that NFD increased pathways corresponding to transporters, secretion system, and two-component system, which were closely associated with bacterial adaptation. The adaptation of bacterial species not only relies on the surrounding microenvironment, such as siderophores, exopolysaccharides, protein toxins but also on the two-component system, which allows a pathogen to adapt its gene expression in response to environmental stimuli29. Besides, the “secretion systems” facilitate protein toxins transport through the physical barriers that the membranes represent30. In this study, the functional prediction of Tax4Fun was consistent with the microbial community changes, indicating that NFD enriched the pathogenic bacteria survival, which represented a considerable health threat to the chicken.

Results of the present study showed that chickens fed with NFD had physiological abnormalities, represented by malnutrition and accumulation of Proteobacteria in the gut, which cannot be effectively ameliorated just by adjusting the proportion of starch and dextrose in NFD. To overcome the limitations of NFD, Moughan et al.31 proposed an approach that the animal is fed a purified diet containing enzyme-hydrolyzed casein (EHC) as the sole N source to maintain physiologically normal levels of endogenous N flow throughout the intestinal tract. However, the IEAAs losses obtained by this EHC method might be unstable since Ravindran et al.32 found that increasing dietary EHC concentrations increased the flow of IEAAs at the terminal ileum of broiler chickens in a dose-dependent manner. Due to the restricted scope of the present study, we did not investigate the effects of supplementing EHC or casein to NFD on the IEAAs of broiler chickens. However, it is worth performing more investigations on combining the advantages of different methods to optimize the detection method of IEAAs in the future.

Conclusion

Taken together, the present results demonstrated that a higher proportion of dextrose (D/CS = 1 and 0.6) in NFD increases IEAAs by promoting digestive enzymes and mucin secretion. However, the excessive proportion of starch was unsuitable for the chicken to digest NFD (D/CS = 0.14). The broilers in D/CS 0.33 group were closer to the normal digestive physiological state. Thus, the D/CS in NFD at 0.33 might be more appropriate to detect IEAAs of broiler chickens.

Methods

Experimental design, animals, and animal care

The animal care and experimental procedures described in this experiment were conducted according to the Animal Welfare Committee guidelines and had the approval of Ethics committee of Animal Science and Technology College of China Agricultural University (No.AW11059102-1, Beijing, China). And the experiments were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

A total of 210,1-d-old broiler chickens were fed the starter diet up to 27 d. At 28-d-old, chickens with similar body weight were allocated to 5 treatment groups with 6 replicate cages (7 chickens per cage) in each group for a 3-day trial period to estimate IEAAs losses. The five treatment groups comprised a control group (corn-soybean meal), and four NFD groups with different ratios of dextrose to corn starch (D/CS), designated as D/CS 1.00, D/CS 0.60, D/CS 0.33, and D/CS 0.14. We found that the starch content in the control diet was 38.76%, and it was challenging to make a pelleted diet with starch content less than 30% in NFD after the pretest. Therefore, the variation of starch content in NFD was based on 40% in this study to make it feasible to prepare the experimental diet.

The content of starch in the feed was measured according to the instruction of a commercial kit for starch content detection (A148-1–1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). All the diets were pelleted and contained 0.5% titanium dioxide as an indigestible marker for calculating the IEAAs. The reason why 8.88% zeolite was added to NFD is that the zeolite effectively reduces the viscosity of feed during granulation and prevents molten glucose and starch from sticking together and blocking the granulator. In addition, zeolite does not contain nutrients such as protein, which can meet the experimental requirements.

The dextrose and corn starch were purchased from Qinhuangdao Lihua starch Co., Ltd (Qinhuangdao, China), satisfying the corresponding China National Standard GB/T 8885 and GB/T 20,880, respectively. The ingredient composition and AA levels of NFD and control diets are shown in Table 1.

All chickens were raised in conventional cages, and each group was composed of 6 cages, with 7 chickens in each cage (0.7 m2/per cage). The brooding temperature was maintained at 33–35 °C from 1 to 2d, and then the temperature dropped by one degree every two days until 21 °C. The relative humidity was maintained at 65–70% from 1 to 7d, 50–65% from 8 to 31d. The lighting schedule consisted of 24 h from 1 to 2d, 23 h for 3d, 22 h for 4d, 21 h for 5d, and 20 h from 6 to 31d. All birds had free access to feed and water. No animal deaths occurred during the 3-day trial period.

Sample collection

On day 31, one chicken from each replicate was randomly selected to collect blood from the brachial vein and subsequently centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min to harvest serum. Afterward, these chickens were euthanatized by injecting pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body weight). The intestine was immediately removed and demarcated by the end of the duodenal loop, Meckel’s diverticulum, and the ileocecal junction. Approximately 1 cm intestinal segment was excised from the middle portion of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum and then carefully collected in carnoy fixative (G2312, Solarbio, Japan) for Alcian blue-periodic acid-schiff stain (AB-PAS). Another 1 cm ileum segment was collected after washing with ice-cold PBS, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80℃ for subsequent analysis of gene expression. The ileal digesta was gently squeezed from the distal ileum and homogenized using a spatula before being collected in two bacteria-free tubes, and then snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for further analysis of gut microbiota and digestive enzyme activity, respectively. After the digesta was flushed out with ice-cold PBS, the entire ileal mucosa was scraped off using sterilized microscope slides, collected in tubes, nap-freezing in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C for the further analysis of disaccharidase activity. The remaining six chickens in each cage were euthanatized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg BW), intestine removed, and the digesta of terminal ileum (lower half of the ileum) was collected and pooled within a cage, immediately stored in − 80 °C overnight and then freeze-dried using a vacuum freeze dryer (FD-2, Biocool, Beijing, China).

Calculations of IEAAs and AID

After freeze-drying, the diet and digesta were ground and sifted through a 40-mesh sieve to ensure homogeneity. The DM concentration of feed and digesta samples was analyzed based on the methods illustrated in AOAC International33. The feed and digesta samples were hydrolyzed using 6 mol/L HCl at 105 °C for 24 h under N atmosphere, and then the AA concentration was measured by Amino Acid Analyzer (A-300, Membrapure, Germany). TiO2 was determined using the procedure described by Myers et al. 34. Briefly, the homogenized ileal digesta samples were ashed, and then digested using sulphuric acid (7.4 M) and subjected to react with hydrogen peroxide, and the absorbance was measured at 410 nm using a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 2100 pro, Amersham Biosciences, USA).

The IEAAs were calculated as milligrams of amino acid flow per 1 kg of DM intake using the Eq. (1) by Moughan et al.35 The apparent digestibility of DM was calculated using Eq. (2). All the data was expressed on DM basis for calculations.

| 1 |

| 2 |

where: AA ileal digesta represented the AA concentration in terminal ileal digesta (mg/kg of DM); TiO2 diet and TiO2 ileal digesta represented the TiO2 concentrations (%) in the diets and terminal ileal digesta, respectively; DM diet and DM ileal digesta represented the DM concentrations (%) in the diets and terminal ileal digesta, respectively.

Serum metabolites

The glucose, total protein (TP), albumin, and uric acid levels were determined by an automated biochemical analyzer (TBA-120FR, TOSHIBA, Japan). The insulin-like growth factor-1(IGF-1) was detected by IGF-1 600 ELISA kit (DRG, ELA-4140, Germany). The glucagon (GLUN) and insulin (INS) were detected by automatic radioimmunocounter (XH-6080, Xi'an Nuclear instrument Factory, China).

Intestinal morphology

The tissue sections and AB-PAS stain of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum of broiler chickens were prepared by Servicebio Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). The intestinal morphology was measured based on eight representative complete villi in the same AB-PAS stained slide. Mucosal villus height was defined as the length from the tip of the villus to the crypt opening, and the associated crypt depth was determined from the crypt opening to the crypt base. The number of goblet cells was quantified by counting the number of stained goblet cells per 100 um length of villus and present as the average number of goblet cells per 10 villus.

Digestive enzymes

The mucosal tissue (0.2 g) was homogenized (4000 rpm, 10 min) with an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (JIUPIN-92, JIUPIN, WuXi, China) in 6 volumes of saline (4 °C) to collect the homogenate. According to the instructions, the activities of sucrase and maltase were measured (n = 6) using commercial assay kits (A082-21, A082-31, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Furthermore, the data were collected by optical density (all 505 nm) measurement on a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices, LLC, USA).

The intestinal digesta and mucosal samples were immediately snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen. The intestinal digesta (0.2 g) was homogenized (3500 rpm, 10 min) with an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (JIUPIN-92, JIUPIN, WuXi, China) in 9 volumes of saline (4 °C) to collect the homogenate. And then, the amylase, chymotrypsin, lipase activity was determined according to the instruction of the kit (C016-1–1, A080-3–1, A054-2–1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). And the data were collected using a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 2100 pro, Amersham Biosciences, USA).

Microflora analysis of ileal digesta

DNA extraction was performed using a QIAampTM Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagene, No. 51604). High-throughput sequencing of 16S rDNA gene amplicons was performed by Novogene Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) using a NovaSeq PE250 platform (Novogene Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China). The high-quality sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity level, and a total of 1808 OTUs were obtained. And then, the OTUs sequences were annotated with Silva132 database. According to the species annotation, the α diversity and β diversity were further calculated, and the differences between groups were compared to reveal the different characteristics of microbial community structure under different treatments.

Gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from ileum using RNA Easy Fast Tissue/Cell Kit (DP451, Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China), and the concentration and purity of each sample were determined at 260/280 nm. After that, 1ug of total RNA was reversed into the first-strand cDNA using a kit (RR047A, Takara, Kyoto, Japan). Real-time PCR of mRNA was conducted using the ABI 7500 Fluorescent Quantitative PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA). Each RT reaction was carried out by an SYBR Premix ExTaq kit (RR420A, Takara, Kyoto, Japan). The gene-specific primers were commercially manufactured (Table 2; Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and β-actin was chosen as the house-keeping gene. The relative gene expression levels were calculated by the method36. In addition, the protocol of melting curve analysis was set as follows: 95 °C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 34 s; 15 s for 95 °C, 1 min for 60 °C and 15 s for 95 °C.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by SPSS, version 20.0 (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Data distribution was checked by Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA for comparisons among groups and then followed by the Dunnett’s post hoc test. Values are expressed as the mean and pooled SEM (n = 6 per group). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and P values less than 0.01 indicates extremely significant differences.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ping Lu, Kejun Cao, and Zuquan Pi for technical advice and the assistance with animal experiments.

Author contributions

The experimental scheme was designed by Z,HJ. and Y.JM. Besides, W.W., X,YW., C,YH. and W,YL. participated in the experiment process and assisted in sampling. Z,HJ. analyzed data and wrote the paper, Y,JM. and T.M. provided the necessary experimental equipment and key guidance during the experiment process. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. (No. 31772620) and the System for Poultry Production Technology, Beijing Agriculture Innovation Consortium (Project Number: BAIC04–2019).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stein HH, Sève B, Fuller MF, Moughan PJ, de Lange CF. Amino acid bioavailability and digestibility in pig feed ingredients: Terminology and application. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:172–180. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kong C, Adeola O. Comparative amino acid digestibility for broiler chickens and White Pekin ducks. Poult. Sci. 2013;92:2367–2374. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansman AJM, Smink W, van Leeuwen P, Rademacher M. Evaluation through literature data of the amount and amino acid composition of basal endogenous crude protein at the terminal ileum of pigs. Anim. Feed. Sci. Tech. 2002;98:49–60. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(02)00015-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moughan PJ, Rutherfurd SM. Gut luminal endogenous protein: Implications for the determination of ileal amino acid digestibility in humans. Br. J. Nutr. 2012;108:258–263. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512002474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park CS, Ragland D, Helmbrecht A, Htoo JK, Adeola O. Digestibility of amino acid in full-fat canola seeds, canola meal, and canola expellers fed to broiler chickens and pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2019;97:803–812. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adedokun SA, Parsons CM, Lilburn MS, Adeola O, Applegate TJ. Comparison of ileal endogenous amino acid flows in broiler chicks and turkey poults. Poult. Sci. 2007;86:1682–1689. doi: 10.1093/ps/86.8.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golian A, Guenter W, Hoehler D, Jahanian H, Nyachoti CM. Comparison of various methods for endogenous ileal amino acid flow determination in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2008;87:706–712. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adedokun SA, Jaynes P, El-Hack MEA, Payne RL, Applegate TJ. Standardized ileal amino acid digestibility of meat and bone meal and soybean meal in laying hens and broilers. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:420–428. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu PY, Wang J, Wu SG, Gao J, Dong Y, Zhang HJ, Qi GH. Standardized ileal digestible amino acid and metabolizable energy content of wheat from different origins and the effect of exogenous xylanase on their determination in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong C, Adeola O. Ileal endogenous amino acid flow response to nitrogen-free diets with differing ratios of corn starch to dextrose in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013;92:1276–1282. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adedokun SA, Pescatore AJ, Ford MJ, Jacob JP, Helmbrecht A. Examining the effect of dietary electrolyte balance, energy source, and length of feeding of nitrogen-free diets on ileal endogenous amino acid losses in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:3351–3360. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adedokun SA, Adeola O, Parsons CM, Lilburn MS, Applegate TJ. Factors affecting endogenous amino acid flow in chickens and the need for consistency in methodology. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:1737–1748. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-01245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu R, Li J, Soomro RN, Wang F, Feng Y, Yang X, Yao JH. The 15N-leucine single-injection method allows for determining endogenous losses and true digestibility of amino acids in cecectomized roosters. Plos One. 2017;12:e188525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, McClave SA, Martindale RG, Miller KR, Hurt RT. Hypoalbuminemia and clinical outcomes: What is the mechanism behind the relationship? Am. Surg. 2017;83:1220–1227. doi: 10.1177/000313481708301123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey CJ. Uric acid and the cardio-renal effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes. Obes. Metab. 2019;21:1291–1298. doi: 10.1111/dom.13670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swennen Q, Janssens GP, Millet S, Vansant G, Decuypere E, Buyse J. Effects of substitution between fat and protein on feed intake and its regulatory mechanisms in broiler chickens: endocrine functioning and intermediary metabolism. Poult. Sci. 2005;84:1051–1057. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.7.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prewitt TE, D'Ercole AJ, Switzer BR, Van Wyk JJ. Relationship of serum immunoreactive somatomedin-C to dietary protein and energy in growing rats. J. Nutr. 1982;112:144–150. doi: 10.1093/jn/112.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravindran V. Progress in ileal endogenous amino acid flow research in poultry. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechno. 2021;12:5. doi: 10.1186/s40104-020-00526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman S, Liebow C, Isenman L. Conservation of digestive enzymes. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:1–18. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi X, Tester RF. Fructose, galactose and glucose–In health and disease. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2019;33:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montagne L, Piel C, Lallès JP. Effect of diet on mucin kinetics and composition: Nutrition and health implications. Nutr. Rev. 2004;62:105–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moor AE, Itzkovitz S. Spatial transcriptomics: paving the way for tissue-level systems biology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017;46:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moran ET. Gastric digestion of protein through pancreozyme action optimizes intestinal forms for absorption, mucin formation and villus integrity. Anim. Feed. Sci. Tech. 2016;221:284–303. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mentschel J, Claus R. Increased butyrate formation in the pig colon by feeding raw potato starch leads to a reduction of colonocyte apoptosis and a shift to the stem cell compartment. Metabolism. 2003;52:1400–1405. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0495(03)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita T, Tanabe H, Takahashi K, Sugiyama K. Ingestion of resistant starch protects endotoxin influx from the intestinal tract and reduces D-galactosamine-induced liver injury in rats. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004;19:303–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon HD, Lee E, Oh MJ, Kim Y, Park HY. High-glucose or -fructose diet cause changes of the gut microbiota and metabolic disorders in mice without body weight change. Nutrients. 2018;10:761. doi: 10.3390/nu10121829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukhopadhya I, Hansen R, El-Omar EM, Hold GL. IBD-what role do Proteobacteria play? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:219–230. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin NR, Whon TW, Bae JW. Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends. Biotechnol. 2015;33:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahyot S, Oxaran V, Niepceron M, Dupart E, Legris S, Destruel L, Didi J, Clamens T, Lesouhaitier O, Zerdoumi Y, Flaman JM, Martine PC. Role of the LytSR two-component regulatory system in staphylococcus lugdunensis biofilm formation and pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:39. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Journet L, Cascales E. The type VI secretion system in Escherichia coli and related species. EcoSal Plus. 2016;7:1–20. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0009-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moughan PJ, Darragh AJ, Smith WC, Butts CA. Perchloric and trichloraacetic acids as precipitants of protein in endogenous ileal digesta from the rat. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 1990;52:13–21. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740520103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravindran V, Morel PC, Rutherfurd SM, Thomas DV. Endogenous flow of amino acids in the avian ileum as influenced by increasing dietary peptide concentrations. Br. J. Nutr. 2009;101:822–828. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508039974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horwitz, W. & Latimer, G. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 18th ed. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: AOAC International (2005).

- 34.Myers WD, Ludden PA, Nayigihugu V, Hess BW. Technical note: A procedure for the preparation and quantitative analysis of samples for titanium dioxide1. J. Anim. Sci. 2004;82:179–183. doi: 10.2527/2004.821179x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moughan PJ, Marlies Leenaars GS. Endogenous amino acid flow in the stomach and small intestine of the young growing pig. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1992;60:437–442. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740600406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]