Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the properties of the cognitive battery used in the MIND Diet Intervention to Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease. The MIND Diet Intervention is a randomized control trial to determine the relative effectiveness of the MIND diet in slowing cognitive decline and reducing brain atrophy in older adults at risk for Alzheimer’s dementia.

Methods:

The MIND cognitive function battery was administered at baseline to 604 participants of an average age of 70 years, who agreed to participate in the diet intervention study, and was designed to measure change over time. The battery included 12 cognitive tests, measuring the four cognitive domains of executive function, perceptual speed, episodic memory, and semantic memory. We conducted a principal component analysis to examine the consistency between our theoretical domains and the statistical performance of participants in each domain. To further establish the validity of each domain, we regressed the domain scores against a late life cognitive activity score, controlling for age, race, sex, and years of education.

Results:

Four factors emerged in the principal component analyses that were similar to the theoretical domains. In regression equations, we found the expected associations with age, education, and late life cognitive activity with each of the four cognitive domains.

Conclusions:

These results indicate that the MIND cognitive battery is a comprehensive and valid battery of four separate domains of cognitive function that can be used in diet intervention trials for older adults.

Keywords: neuropsychological tests, outcome assessment, episodic memory, executive function, cognition, principal component analysis

INTRODUCTION

Examining the effect of dietary changes on cognitive health has become an important target in the pursuit of brain maintenance strategies. As such, the literature on dietary interventions has grown over the last several years, providing evidence that dietary changes hold promise in improving cognitive function and reducing the risk of cognitive decline. Despite this progress, our ability to draw conclusions may be limited because of the great variability in how the outcome of cognitive function is measured across studies.

A recent systematic review included 56 studies examining the association between diet and cognition (van den Brink et al., 2019) and revealed substantial variability in the measurement of cognitive outcomes across studies. Fewer than half of the observational studies used a cognitive battery with multiple tests (e.g., ≥ 4 tests). Of the remaining studies, outcome measures included cognitive status only (e.g., neurocognitive diagnosis), a single global screener (e.g., Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS): Teng & Chui, 1987), subjective reports of cognitive function, or mortality. Six randomized control studies were described (Knight et al., 2016; Martinez-Lapiscina et al., 2013a; Martinez-Lapiscina et al., 2013b; Smith et al., 2010; Valls-Pedret et al., 2015; Wardle et al., 2000) and all of them, with one exception (Maratinez-Lapiscina et al., 2013a), included batteries of multiple tests. All the studies with batteries of multiple tests included individual tests with established psychometric properties; however, only one of those studies (Knight et al., 2016) assessed properties of the entire battery. Specifically, Knight and colleagues (2016) used a principal components analysis with oblique rotation and found that their battery of 11 tests loaded onto four factors. However, they provided limited information regarding the validity of their battery. Given the importance of cognitive function as an outcome variable, increased knowledge of how cognitive batteries perform in different populations is necessary for accurate association with predictors of interest, such as diet.

In the present study, we evaluated the construct validity of a cognitive function battery that was used in the MIND Diet Intervention. The MIND Diet Intervention is a randomized control trial to determine the relative effectiveness of the MIND diet in reducing markers of underlying biological mechanisms for AD and vascular dementia. The MIND diet, Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay, where DASH stands for Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, can best be described through its component parts of 10 brain healthy food groups (green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, nuts, berries, beans, whole grains, seafood, poultry, olive oil and wine) and 5 unhealthy food groups (red meats, butter and stick margarine, cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried/fast foods) (Morris, et al., 2015). A MIND diet score, defined previously (Morris, et al., 2015), was developed to facilitate the understanding of these nutrients on health outcomes, including cognition. The MIND diet has been associated with less cognitive decline (Morris, et al, 2015) and lower risk of AD in several studies (van den Brink et al., 2019). Additionally, there is evidence that the MIND diet may reduce risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in populations outside the US that are younger and are culturally distinct from the US older adult population (Hosking, et al., 2019).

The cognitive function battery was chosen to include four relevant domains for measuring change in aging: executive function, perceptual speed, episodic memory, and semantic memory. We hypothesized that the 12 individual tests of the battery would group into four theoretical cognitive domains and would have expected associations with age, education, and late life cognitive activity.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 604 community volunteers enrolled in the MIND Diet Intervention to Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease. The majority of participants was white (89%) and female (65%) and had a mean age of 70 (SD = 4.2). The mean years of education, ascertained with the question “What is the highest grade or year of school you completed”, was 17 (SD = 2.6), as described in Table 2. One-half of the participants (N=302) were randomized to the control arm and the other half to the intervention arm. The inclusion criteria were: 65–84 years old, body mass index > 25 k/m2, family history of dementia but without personal cognitive impairment as measured by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA: Nasreddine et al., 2005) ≥ 22, suboptimal diet as measured by a MIND score (Morris et al. 2015) ≤ 8 out of 14, agree to not take any non-prescribed vitamins or supplements, and live in a household in which they are the only MIND participant.

Table 2.

Characteristics of MIND study population

| N = 604 | |

|---|---|

| Key Demographics | |

| Age (years, mean (SD)) | 70.4 (4.2) |

| Sex (% female) | 65.1 |

| Education (years, mean (SD)) | 16.9 (2.6) |

| Race (% non-Hispanic White) | 89.1 |

| Cognitive activity score (mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.6) |

Data Collection and Randomization

Participants completed a battery of tests at baseline before being randomized into one of two dietary intervention-counselling sessions: the MIND diet plus weight loss group or the standard diet plus weight loss group. The two groups utilized the same multi-pronged strategy for diet compliance, which included: 1. Personalized diet plans and strategies, 2. Multiple compliance aids (e.g. refrigerator charts), 3. Group motivation strategies (e.g. group cooking classes), and 4. Frequent weight monitoring and check-ins. Dieticians lead a similarly structured program for both groups in order to promote equivalent adherence. Trained research assistants administered the battery of cognitive function tests to participants in one of two site locations (Boston or Chicago); all batteries were administered in-person and in a quiet setting, free from major distractions. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Boards of Rush University Medical Center and Harvard School of Public Health.

Designing the Battery

We designed a cognitive battery that would fit several criteria for this randomized control trial in a community-based sample. First, we selected tests that have been shown in previous research to detect changes in cognition of older persons over time. Second, the entire battery had to be administered in 45 minutes or less, to not place an undue burden on participants. Third, we wanted tests to measure a wide range of abilities across different domains of function, in order to minimize possible floor and ceiling effects. Finally, we wanted tests that could be reliably administered by trained research assistants in a standardized manner across the two study sites.

The battery included 12 public domain tests that were categorized into four theoretical domains, as Table 1 demonstrates: executive function, perceptual speed, episodic memory, and semantic memory. Two tests in the battery were chosen to measure executive function: Trail Making Test B (Reitan & Wolfson, 1985) and the Flanker Inhibitory Control test from the NIH Toolbox (Weintraub et al., 2013). Three tests were chosen to assess perceptual speed: the Oral Symbol Digit Modality Test (Smith, 1982), the Pattern Comparison test (Weintraub et al., 2013), and Trail Making Test A (Reitan & Wolfson, 1985). Five tests were administered to assess episodic memory: Word List Memory, Word List Recall, Word List Recognition (Morris et al., 1989), East Boston Story Immediate Recall, and East Boston Story Delayed Recall (Albert et al., 1991). Two tests measured semantic memory: Category Fluency (Animals/Fruits and Vegetables) (Morris et al., 1989) and the Multilingual Naming Test (Ivanova et al., 2013). For each of the tests, we calculated z scores, using the mean and standard deviation of all participants. We then averaged the z scores of the component tests for each domain. Table 2 lists the mean, standard deviation, and range for each of the tests according to their domains.

Table 1.

The MIND Cognitive Battery

| Executive Functioning | Trail Making Test B | Trail Making Test B requires participants to alternate between numbers and letters in order. This test is timed and completed on paper. Administrators correct errors during execution of the test. The Trail Making Test measures processing speed and mental flexibility. As such, it is sensitive to detecting cognitive impairment across a wide range of disorders, including cognitive decline in aging. Halstead Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. |

Scoring: time to complete in seconds | Reitan & Wolfson, 1985. | |

| Flanker Inhibitory Control | The Flanker Inhibitory Control tests is a test in the NIH-TB Cognition Battery tests and administered via computer screen to participants. The test requires participants to inhibit visual attention to irrelevant tasks that are presented in congruent and incongruent trials. The scoring algorithm integrates accuracy and reaction time over 40 trials. | Scoring: NIH toolbox Range: 0–10 | Weintraub, Dikmen, Heaton, Tulsky, Zelazo, Bauer, et al., 2013. | ||

| Perceptual Speed | Oral Symbol Digit Modality Test | Participants view a key made up of unique symbols matched with numbers 0–9. They then view the symbols with the numbers missing and their task is to call out the number from the key that corresponds to the symbol. They are given 120 seconds. | Scoring: NIH toolbox 0 – 144 | Smith, 1982. | |

| Pattern Comparison | Pattern Comparison is a test in the NIH-TB Cognition Battery tests and administered via computer screen to participants. Pattern Comparison measures choice reaction time, by having participants compare visual patterns to see if they are the same or different. They are given 90 seconds to complete. | Scoring: NIH toolbox Range: 0–130 | Weintraub, Dikmen, Heaton, Tulsky, Zelazo, Bauer, et al., 2013. | ||

| Trail Making Test A | The Trail Making Test A is a measure of visual attention and processing speed. Trail Making Test A requires participants to connect numbers in order. This test is timed and completed on paper. Administrators correct errors during execution of the test. Halstead Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. |

Scoring: time to complete in seconds | Reitan & Wolfson, 1985. | ||

| Episodic Memory | Word List Memory | The administrator reads a list of 10 words and then requests the participant to repeat all the words they can remember. There are three trials and the score is the total number of words repeated from all 3 trials. The consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD): | Scoring: Trials 1, 2, 3 Range 0–10, for each trial. Performance Range = 0–30 | Morris, Heyman, Mohs, Hughes, van Belle, Fillenbaum, Clark, 1989. | |

| Word List Recall | After a delay, the administrator asks the participant to repeat all of the words from the list they had heard earlier. (CERAD) | Scoring: Range 0–10 | Morris, Heyman, Mohs, Hughes, van Belle, Fillenbaum, Clark, 1989. | ||

| Word List Recognition | Participants are presented with sheets with 4 words on each and asked to identify the correct word from the word list they had previously seen. (CERAD) | Scoring: Range 0–10 | Morris, Heyman, Mohs, Hughes, van Belle, Fillenbaum, Clark, 1989. | ||

| East Boston Story Immediate Recall | The administrator reads a short action story, written in everyday language and then asks participants to repeat as much of the story immediately afterwards. The score is based on the total number of details the participant expresses. | Scoring: Range 0–12 | Albert, Smith, Scherr, Taylor, Evans, Funkenstein,1991. | ||

| East Boston Story Delayed Recall | Participants are prompted to tell as much as they can remember about the short story they had heard earlier. The score is based on the total number of details the participant expresses. | Scoring: Range 0–12 | Albert, Smith, Scherr, Taylor, Evans, Funkenstein,1991. | ||

| Semantic Memory | Verbal Fluency | Verbal fluency is measured by two semantic verbal fluency trials. The administrator instructs participants to say as many words as they can from a given category in 1 minute. The two categories are: 1. Animals and 2. Fruits and Vegetables. | Scoring: Total number of words generated for both trials. 0+ | Morris, Heyman, Mohs, Hughes, van Belle, Fillenbaum, Clark, 1989. | |

| Multilingual Naming Test | The Multilingual Naming Test measures naming skills and detects naming impairments in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Participants provide the name for each of the 32 black and white drawings | Scoring: Range 0–32 | Ivanova, Salmon, Gollan, 2013. |

Late-Life Cognitive Activity Assessment

During the baseline interview, participants reported on the frequency of engagement in late-life cognitive activities. They were asked to rate: 1. How much time they spent reading each day, 2. How often they visited a library in the last year 3. How often they read the newspaper in the past year, 4. How often they read magazines in the past year and 5. How often they read books in the past year, 6. How often they wrote letters in the past year and 7. How often they played games such as checkers, or other board games, cards, puzzles, etc. Participants rated each item on a five-point scale, with higher scores indicating more frequent cognitive activity. We then created a composite cognitive activity score by averaging the 7 items as previously described (Wilson, et al., 2012).

Data Analysis

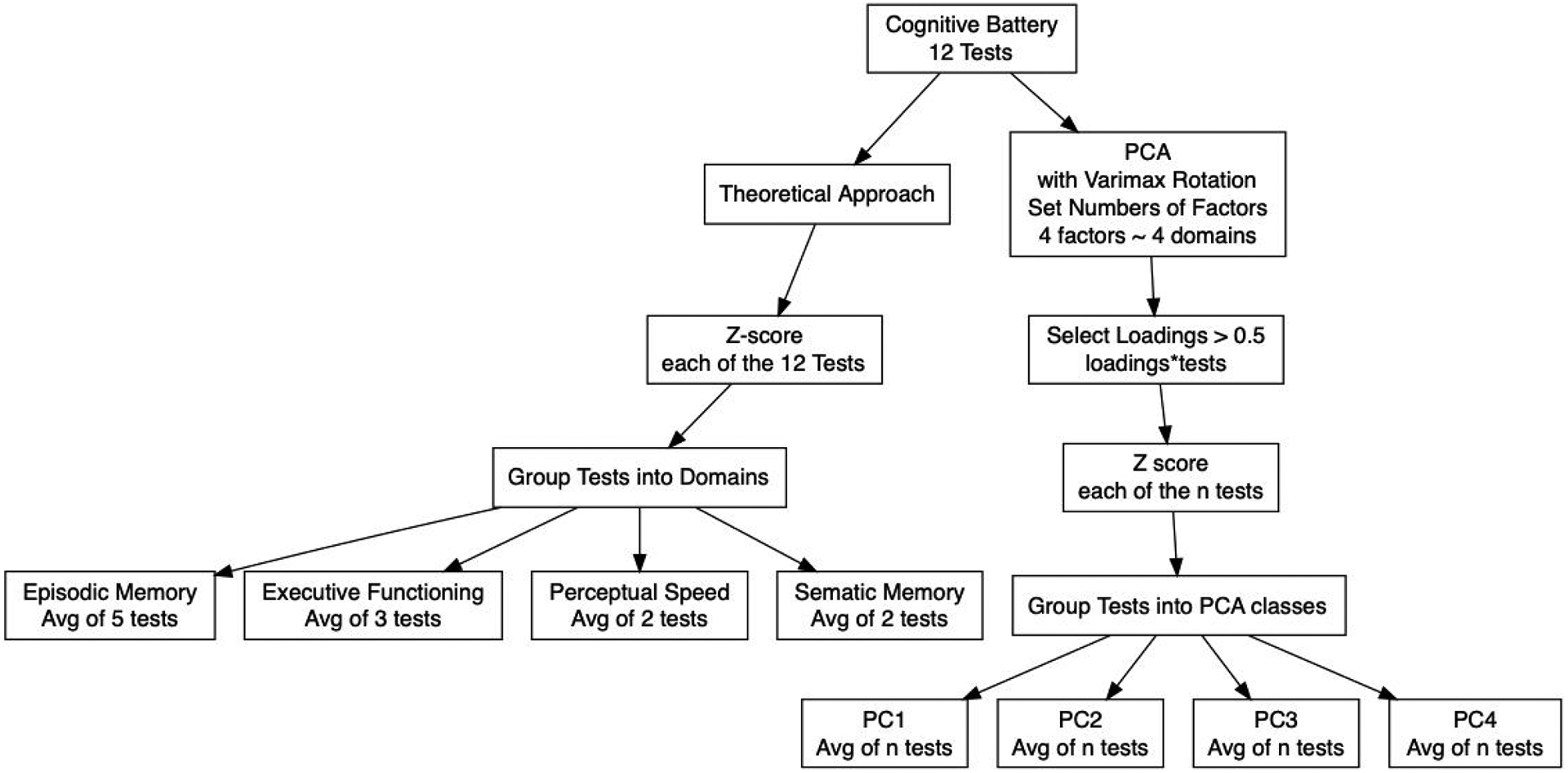

We specified a conceptually based grouping of the tests into functional domains: executive function, perceptual speed, episodic memory, and semantic memory. Next, we conducted a principal-components factor analysis with varimax rotation on the 12 cognitive tests to evaluate whether factor loadings – or empirically based groupings - were consistent with the conceptually based groupings. Tests with loadings of 0.5 or greater were grouped on a common factor, and Rand’s statistic (Rand, 1971) was used to assess the fit between the theoretical and empirically based groupings. Figure 1 displays the steps in the theoretical and statistical processes.

Figure 1.

Validation Process of the MIND Cognitive Battery

We ran multiple linear regression models in two-steps in order to examine the associations of the composite measures of each cognitive domain with late-life cognitive activity. We first regressed each domain against the demographic variables of age, sex, race, and education. In a second step we included cognitive activity in the same model. Statistical analyses were conducted using R programming version 3.6.

RESULTS

Psychometric Properties of the Cognitive Battery

The means and standard deviations of each of the 12 cognitive function tests used in the analyses are shown in Table 3. We included all 12 tests in a principal component factor analysis with a varimax rotation to examine the empirically based groupings of these tests and compared them with the theoretical groupings referred to in Table 1: executive function, perceptual speed, episodic memory, and semantic memory. Rand’s statistic was 0.82 (p<0.001), indicating a good fit between the factor analytic results and the hypothesized grouping.

Table 3.

Psychometric information on 12 cognitive tests

| Cognitive Tests | Means of Raw Scores | SD | Hypothesized Domain | Rotated Factor Loadings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA1 | PCA2 | PCA3 | PCA4 | ||||

| Word list Memory | 22.2 | 3.4 | Episodic memory | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.14 | 0.24 |

| Word list Recall | 7.1 | 1.9 | Episodic memory | −0.01 | 0.84 | 0.9 | 0.05 |

| Word list Recognition | 9.9 | 0.5 | Episodic memory | 0.19 | 0.7 | −0.03 | −0.14 |

| East Boston Immediate | 10.4 | 1.6 | Episodic memory | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.9 | 0.05 |

| East Boston Delayed | 10.0 | 1.6 | Episodic memory | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.89 | 0.1 |

| Flanker Inhibitory | 7.9 | 0.7 | Executive Functioning | 0.76 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Trails A | 33.9 | 12.7 | Executive Functioning | 0.67 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.32 |

| Trails B | 84.8 | 42.4 | Executive Functioning | 0.57 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.46 |

| Pattern Comparison | 46.1 | 10.8 | Perceptual Speed | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.1 | −0.09 |

| Oral Digit Symbol Test | 70.3 | 13.4 | Perceptual Speed | 0.57 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.45 |

| Multilingual Naming Test | 30.3 | 2.1 | Semantic Memory | 0.26 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.52 |

| −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.81 | ||||

The empirically based groupings revealed four factors, as demonstrated in Table 3. Four factors emerged that were generally consistent with the theoretical groupings but were different in minor ways. The first factor that emerged included all tests from the theoretical domains of executive function (Trail Making Test B, Flanker Inhibitory Control) and perceptual speed (Oral Digit Symbol Modality Test, Pattern Comparison, Trail Making Test A). A second factor emerged that included the word list tests (Word list memory, word list delayed recall, word list recognition) from the episodic memory domain. A third factor contained the two tests from the episodic memory domain (East Boston Immediate Recall, East Boston Delayed Recall), and the fourth factor contained the two tests in the semantic memory domain, consistent with the theoretical conceptualization.

Association of the Cognitive Battery with Other Variables

Table 4 shows the associations of demographic variables and frequency of cognitive activity with the theoretical cognitive domains. In the multivariable-adjusted model, age was associated with lower cognitive scores in all domains. Compared to women, men had a significantly lower cognitive score in episodic memory β = −0.269, SE 0.056, p< 0.001) and perceptual speed (β =−0.182, SE 0.060, p=0.003). No significant sex differences were noted in executive function (p=0.076) and semantic memory (p=0.663). Education was associated with higher scores for episodic memory (β = 0.024, SE 0.011, p=0.028) and semantic memory (= 0.029, SE0.053, p<0.001), whereas frequency of cognitive activity was associated with executive function (β = 0.144, SE 0.055, p=0.009), perceptual speed (β = 0.208, SE 0.051, p<0.001), and semantic memory (β = 0.196, SE 0.053, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Association of theoretical cognitive domain with demographic variables.

| Cognitive Domain | Model Terms | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | ||

| Executive Functioning | Age | −0.055 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | −0.056 | 0.007 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, Men | 0.105 | 0.065 | 0.107 | 0.115 | 0.065 | 0.076 | |

| Race, African Am | −0.822 | 0.099 | < 0.001 | −0.781 | 0.100 | < 0.001 | |

| Education | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.251 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.902 | |

| Cog Activity | 0.144 | 0.055 | 0.009 | ||||

| Perceptual Speed | Age | −0.050 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | −0.052 | 0.007 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, Men | −0.196 | 0.061 | 0.001 | −0.182 | 0.060 | 0.003 | |

| Race, African Am | −0.644 | 0.093 | < 0.001 | −0.584 | 0.093 | < 0.001 | |

| Education | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.454 | −0.009 | 0.012 | 0.443 | |

| Cog Activity | 0.208 | 0.051 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Episodic Memory | Age | −0.025 | 0.006 | < 0.001 | −0.025 | 0.006 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, Men | −0.273 | 0.056 | < 0.001 | −0.269 | 0.056 | < 0.001 | |

| Race, African Am | −0.075 | 0.085 | 0.380 | −0.061 | 0.086 | 0.482 | |

| Education | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.011 | 0.028 | |

| Cog Activity | 0.049 | 0.047 | 0.299 | ||||

| Semantic Memory | Age | −0.030 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | −0.032 | 0.007 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, Men | −0.041 | 0.063 | 0.516 | −0.027 | 0062 | 0.663 | |

| Race, African Am | −0.700 | 0.096 | < 0.001 | −0.643 | 0.096 | < 0.001 | |

| Education | 0.045 | 0.011 | < 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.012 | 0.018 | |

| Cog Activity | 0.196 | 0.053 | < 0.001 | ||||

Age was centered to 75 years and education was centered to 12 years.

DISCUSSION

We validated a cognitive function battery that is being used in a clinical trial examining the effect of diet on cognition in older adults. Twelve individual tests were included and grouped into four theoretical domains: executive function, perceptual speed, episodic memory, and semantic memory. We then conducted a principal component analysis of all tests and found that our theoretical groupings were similar to the results from the principal component analysis, strengthening our confidence that the measures are capturing the cognitive domains of interest. Similarly, we found that the battery was associated with age, education, and late-life cognitive activity in the expected directions, further demonstrating the validity of our battery.

Although highly concordant, the domains that emerged from the principal component analysis varied in minor but important ways from our theoretical domains. First, the tests that represented our theoretical episodic memory domain were classified into two groups in the PCA, with the word list learning, recall, and recognition loading on one factor and the immediate and delayed story recall loading on a separate factor. Word lists, stories, or both are commonly used to measure memory and are commonly recognized as tasks that tap different abilities within episodic memory. Specifically, deficits on a word-list task presume higher order encoding and retrieval deficits, associated with subcortical deficiency, whereas poor performance on a story memory task implies underlying deficits in encoding and storage with mesial temporal implications (Zahonde et al., 2011). Studies comparing wordlist tasks with story tasks have also provided evidence that the two tasks are distinct in terms of practice effects (Gavett et al., 2016), performance of non-demented persons with Parkinson’s disease (Zahonde et al., 2011), and their ability to distinguish causes of dementia in certain samples (Perri et al., 2013). Given substantial evidence that these two memory tasks perform differently, it is not unexpected that they would load on different factors in our study.

The second finding that varied from our theoretical conceptualization was the collapsing of the domains of executive function and perceptual speed onto one factor. This finding was somewhat unexpected, given the last 20 years of research that has examined executive function following the influential article by Miyake and colleagues (2000). They revealed a model in which the three factors of “shifting,” updating,” and “inhibition” emerged as separable factors, but had moderate correlations with each other (Miyake et al., 2000). A recent systematic review of this body of executive function literature revealed that the unity and diversity in how the domain of executive function abilities manifest themselves may change across the lifespan (Karr et al., 2018). Perhaps most importantly, the results from this systematic review reinforced our imperfect understanding of executive function as a domain. In our study, we examined tasks that tap inhibition (Flanker Inhibitory Control) and shifting (Trail Making Test B), but not updating and these tests loaded on one factor along with other tests, all of which were timed. As such, it is possible that the loadings on this factor reflect a time element that may override the influence of the individual tasks and underlying latent variables. The empirical findings regarding the domain of semantic memory were consistent with the conceptual groupings. Thus, despite minor discrepancies between conceptual and empirical findings, our study provides evidence that this cognitive battery is measuring distinct domains that are comparable to our theoretical understanding of these abilities.

We found several important associations of our battery with variables of interest in aging. We found an interesting interplay in the relationship between cognitive activity, education and cognitive performance. Specifically, we found that frequency of cognitive activity in late life, compared with education, was more strongly associated with cognitive performance in all domains, with the exception of episodic memory. Finding a stronger association with late-life cognitive activities compared to years of education is not surprising, given the implication from recent research that years of formal education have been found to contribute less to cognitive function than late-life cognitive activities (Wilson, et al, 2019). However, it is not clear why episodic memory would have a stronger association with education and further research is needed to understand this finding. We also found sex differences, consistent with previous research. The most outstanding finding was that women outperformed men in episodic memory, a finding that is consistent with sex differences found earlier in life and has also been observed in the oldest old (Golchert, et al., 2019).

Important progress has been made in examining cognitive batteries or cognitive composites in studies examining the preclinical stage of dementia (Weintraub et al., 2017). To measure the effect of treatments to reduce risk or prevent cognitive decline, cognitive batteries must be able to detect small changes before a diagnosis of dementia. Thus far, there is evidence that it is feasible to detect cognitive change in the preclinical stage (Mortamais et al., 2017), and researchers in the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia project have developed guidelines for cognitive outcomes to be used in future studies on preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (Ritchie et al., 2017). Future directions of dietary studies may benefit from heeding recommendations from the studies on preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, in addition to examining the validity of their study-specific battery.

Our study has important limitations. Our sample was predominantly white with an average of 17 years of education and was ethnically and linguistically homogenous. As such, these results will need to be validated in more diverse groups of people to generalize the results. Additionally, we did not compare the performance of this battery to an objective sample or control group. Nor did we evaluate the battery over time, in a population with disease progression, from cognitively normal to dementia. Future longitudinal studies are needed to assess the ability of this battery to measure change over time.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest Disclosures. We have no conflicts of interest to report.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging, RO1AG052583

We would like to acknowledge all the participants and staff who dedicated time, goodwill, and energy to this study. We acknowledge the astute insight provided by Dr. Martha Clare Morris that led to this work and express our utmost gratitude for her direction and support, which has allowed us to continue advancing the field of diet and cognitive aging.

Contributor Information

Kristin R. Krueger, Rush Institute for Healthy Aging, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

Klodian Dhana, Rush Institute for Healthy Aging, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL.

Neelum T. Aggarwal, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

Konstantinos Arfanakis, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL.

Vincent J. Carey, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Frank M. Sacks, Nutrition Department, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA

Lisa L. Barnes, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

References

- Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH (1991). Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Neuroscience; 57: 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavett BE, Gurnani AS, Saurman JL, Chapman KR, Steinberg EG, Martin B,…Stern RA (2016). Practice effects on story memory and list learning tests in the neuropsychological assessment of older adults. PLoS ONE; 11(10): 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golchert J, Roehr S, Luck T, Wagner M, Fuchs A, Wiese B…..Riedel-Heller S (2019). Women outperform men in verbal episodic memory even in oldest-old: 13-yar longitudinal results of the AgeCoDe/AgeQualiDe Study. Journal of Alzheimers Disease: 69(3): 857–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking DE, Eramudugolla R, Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ (2019). MIND, not Mediterranean diet related to 12-year incidence of cognitive impairment in an Australian longitudinal cohort study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia; 15(4): 581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova I, Salmon DP, Gollan TH (2013). The Multilingual Naming Test in Alzheimer’s Disease: Clues to the origin of Naming Impairments. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2013; 19(3): 272–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karr JE, Areshenkoff CN, Rast P, Hofer SM, Iverson GL, Garcia-Barrera MA (2018). The unity and diversity of executive functions: A systematic review and re-analysis of latent variable studies. Psychological Bulletin: 144(11): 1147–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight A, Bryan J, Wilson C, Hodgson J, Davis C, Murphy K (2016). The Mediterranean diet and cognitive function among healthy older adults in a 6-month randomised controlled trial: the MedLey Study. Nutrients; 8:579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Clavero P, Toledo E, Estruch R, Salas-Salvado J, San Julian B, Sanchez-Tainta,…Martinez-Gonzalez MA (2013a). Mediterranean diet improves cognition: the PREDIMED-Navarra randomised trial. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry; 84:1318–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Clavero P, Toledo E, San Julian B, Sanchez-Tainta A, Corella D,…Martinez-Gonzalez MA (2013b). Virgin olive oil supplementation and long-term cognition: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomized trial. Journal of Nutritional Health and Aging; 17:544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson M,J, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology; 41 (1): 49–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Clark C (1989). The consortium to establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD): I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology; 39:1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT (2015). MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dementia. 11(9). 1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortamais M, Ash JA, Harrison J, Kaye J, Kramer J, Randolph C, Pose C,…Ritchie K (2017). Detecting cognitive changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A review of its feasibility. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 13, 468–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips N,A, Bedirian B, Charbonneua S, Whitehead V, Collin I,…Chertkow H (2005). The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of American Geriatric Society; 53(4): 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri R, Fadda., Caltagirone C, Carlesimo GA (2013). Word list and story recall elicit different patterns of memory deficit in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, subcortical ischemic vascular disease, and Lewy body dementia. Journal of Alzheimers Disease. 37 (1): 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand MW (1971). Objective criteria for the evaluation of clustering methods. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 66: 846–850. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM & Wolfson D (1985). The Halstead Reitan neuropsychological test battery. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie K, Ropacki M, Albala B, Harrison J, Kaye J, Kramer J,…Ritchie CW (2017). Recommended cognitive outcomes in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: Consensus statement from the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia project. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 13, 186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Craighead L, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Browndyke JN,… Sherwood A (2010). Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, exercise, and caloric restriction on neurocognition in overweight adults with high blood pressure. Hypertension; 55: 1331–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A (1982). Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual – Revised. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, Chui HC (1987). The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) Examination. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 48(43), 314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M, Corella D, de la Torre R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA,…Ros E (2015). Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175: 1094–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink AC., Brouwer-Brolsma EM, AM Berendsen A, & van de Rest O (2019). The Mediterranean, dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) Intervention for neurodegenerative delay (MIND) diets are associated with less cognitive decline and a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease – a review. Advances in Nutrition: 10:1040–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Rogers P, Judd P, Taylor MA, Rapoport L, Green M, Nicholson Perry K (2000). Randomized trial of the effects of cholesterol-lowering dietary treatment on psychological function. American Journal of Medicine; 108: 547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Carrillo MC, Tomaszewski Farias S, Goldberg TE, Hendrix JA, Jaeger J,…Randolph C (2017). Measuring cognition and function in the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 4, 64–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ,…Gershon RC (2013). Cognition Assessment using the NIH toolbox. Neurology; 80: S54–S64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Yu L, Lamar M, Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Bennett DA (2019). Education and cognitive reserve in old age. Neurology:92(10): 1041–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Segawa E, Boyle PA, Bennett DA (2012). Influence of late-life cognitive activity on cognitive health. Neurology;Apr 10; 7(15): 1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahonde LB, Bowers D, Price CC, Bauer RM, Nisenzon A, Foote KD, Okun MS (2011). The case for measuring memory with both word lists and stories prior to DBS in Parkinson’s disease. Clinical Neuropsychology; 25(3): 348–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]