Abstract

Background: The aim of flexor pollicis longus (FPL) repair is to create a construct that is strong enough to withstand forces encountered during rehabilitation and to achieve an optimal active range of motion. The aim of this study was to: (1) assess factors influencing active thumb interphalangeal (IP) joint flexion; and (2) assess the factors associated with reoperation. Methods: Retrospectively, 104 patients with primary repair of a Zone II FPL laceration from 2000 to 2016 were identified. A medical chart review was performed to collect patient-, injury-, and surgery characteristics as well as the degree of postoperative active IP-flexion and occurrence of reoperation. Bivariate analyses were performed to identify factors influencing active IP-flexion and factors associated with reoperation. Results: The reoperation rate was 17% (n = 18) at a median of 3.4 months (range: 2.3-4.4). Indications for reoperation mainly included adhesion formation (n = 10, 56%) and re-rupture (n = 5, 28%). The median range of active IP-flexion was 30° (interquartile range [IQR]: 20-45) at a median of 12.4 weeks (IQR: 8.1-16.7). Solitary injury to the thumb (β = 17.9, P = .022) and the use of epitendinous suture (β = 10.0, P = .031) were associated with increased active IP-joint flexion. No factors were statistically associated with reoperation. Conclusions: About 1 in 5 patients undergo reoperation following primary repair of a Zone II FPL laceration, mostly within 6 months of initial surgery. The use of epitendinous suture is associated with greater active IP-flexion. Patients with multiple digits injured accompanying a Zone II FPL laceration have inferior IP-joint motion.

Keywords: flexor tendon, flexor pollicis longus, FPL, reoperation, interphalangeal flexion, digits, anatomy, tendon, basic science

Introduction

The aim of flexor pollicis longus (FPL) repair is to create a construct that is strong enough to withstand forces encountered during rehabilitation as the tendon heals. Postoperative complications include adhesion formation and re-rupture.

Several studies report that optimal active motion after digital flexor tendon repair is achieved when using robust multistrand core sutures1,2 and an early active rehabilitation program.2,3 Age above 50 years old 4 and Zone II injuries 2 are associated with diminished range of motion after FPL repair. Reoperation rates after flexor tendon repair range from 6% to 11%.5,6 Notably, Zone II is specifically challenging because it is prone to postoperative adhesions due to the complex pulley system. Several studies have reported factors associated with reoperation specifically after Zone II flexor tendon repair, including age, concomitant injury, and type of repair technique.7,8

However, these previous studies mostly focus on the fingers and not the thumb. There is a limited understanding of factors associated with the interphalangeal (IP)-joint flexion range of motion and reoperation rates after Zone II FPL repairs. We tested the null hypothesis that there are no factors associated with final active IP-joint flexion and reoperation after primary Zone II FPL repairs.

Methods

After institutional review board approval, we retrospectively identified adult patients that underwent primary direct FPL repair in Zone II between January 1,2000 and September 30, 2016 at 3 urban academic medical centers in Northeastern United States using Current Procedural Terminology codes and International Classification of Diseases codes (Supplemental Appendix 1). Zone II tendon injuries were defined as injuries between the A1 pulley and A2 pulley of the thumb. All patients were verified through medical chart review (n = 391). We excluded patients who did not have a direct FPL repair (n = 162), a concomitant thumb phalangeal fracture (n = 64), amputation of the thumb (n = 42), a partial FPL laceration (n = 13), were miscoded (n = 5), or were pregnant (n = 1) (Supplemental Figure 1). A total of 104 patients were included in the analyses.

A medical chart review was performed to collect data regarding patient, injury, and surgery characteristics along with postoperative complications and the degree of active flexion of the IP-joint of the thumb. Reoperation was defined as any unplanned surgical procedure performed on the thumb after the initial surgery. The degree of active flexion of the thumb IP joint was extracted from the medical chart as reported by the treating physician or occupational therapist in 57 (55%) of the patients. The last reported degree of IP-flexion was used, which was after reoperation in 8 patients (14%). Additionally, we recorded postoperative complications that did not lead to a reoperation, including stiffness reported in the medical charts, clinical re-rupture, and sensory abnormalities. Follow-up was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the date of last documented visit at one of our institutions.

Study Population

The 104 identified patients had a median age of 34.9 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 26.3-48.2), and the majority (n = 73, 70%) were male. Median follow-up was 2.1 years (IQR: 0.30-7.4). The mechanisms of injury were sharp (n = 83, 80%), saw (n = 20, 19%), and 1 patient (0.96%) had a crush injury. Hand dominance was recorded in the charts for 87 patients (84%), and the dominant hand was affected in 31 patients (36%). In 90 patients (87%), only the thumb was affected, whereas in 14 patients (13%) there was involvement of other digits of the same hand. A digital arterial injury was present in 11 patients (11%) of which 7 (6.7%) were repaired. A digital nerve injury was present in 67 patients (64%), these were all repaired.

Surgical Procedure

Surgery was performed by 38 surgeons of which 5 surgeons performed 10 or more surgeries each, accounting for 52% of the surgeries. In 95 patients, the time of injury was reported in the medical charts and the median time from injury to initial surgery was 7 days (IQR: 2-11). A Kessler repair technique was performed in 69 patients (71%), a Modified Becker repair technique in 14 patients (14%) and other repair techniques including a cruciate repair, a horizontal mattress suture or a Bunnell suture were performed in 14 patients (14%). In most patients, a 4-strand repair was used (n = 72, 82%), followed by a 6-strand repair in 11 patients (13%) and a 2-strand repair in 5 patients (5.7%). An additional epitendinous suture was used in 55 patients (55%). Pulley venting was performed in 24 patients (24%), where mostly the A1-pulley was vented (n = 18, 78%) followed by the A2-pulley (n = 5, 22%). In 32 patients (31%), the FPL was retrieved at the level of the wrist crease necessitating an additional incision. All patients were splinted postoperatively. During rehabilitation, most patients followed the Modified Duran protocol (n = 66, 63%) and others followed the early active motion protocol (n = 3, 2.9%) or a passive motion protocol (n = 1, 0.96%). In 34 patients (33%), the rehabilitation program was unclear from the medical charts.

Statistical Analysis

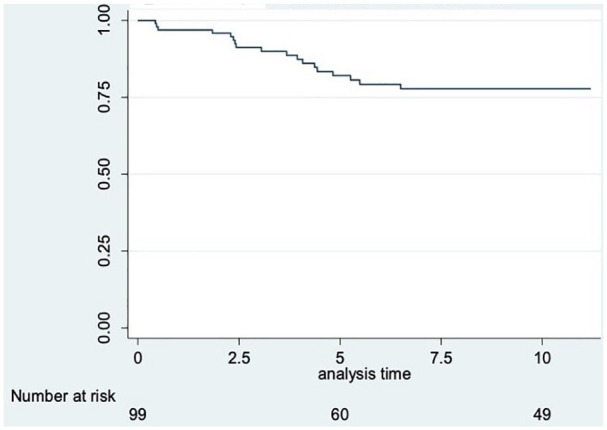

Categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages. Continuous variables were presented as median and IQR. To evaluate the factors associated with reoperation, the Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U-test for nonparametric variables. A Kaplan-Meier curve was plotted to illustrate the survival time to reoperation (Figure 1). We compared patients with and without records of active IP joint flexion, and concluded that these groups were comparable (Supplemental Appendix 2). Bivariate analyses were performed to evaluate what factors influenced the degree of active flexion of the IP joint using the Mann-Whitney U test for dichotomous explanatory variables and the Spearman’s rank for parametric variables. A P-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. We used STATA 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) to perform all analyses.

Figure 1.

Survival time (months) to reoperation.

Results

The median active IP-flexion was 30° (IQR: 20-45) last measured at a median of 12.4 weeks (IQR: 8.1-16.7) postoperatively. In the bivariate analysis, reduced IP joint flexion was associated with older age (β = 0.29, P = .03) and with injuries involving multiple digits (30° [IQR: 20-45] vs. 10° [IQR: 10-20], P = .01). Epitendinous suture use was associated with improved active IP-flexion (32.5° [IQR: 20-45] vs. 27.5° [IQR: 17.5-31.5], P = .04) (Tables 1 and 2). Of the patients with available IP joint flexion data, 30 (53%) had an epitendinous suture of which 5 patients underwent a tenolysis (17%). Of the other 27 (47%) patients who did not have an epitendinous suture, 5 (19%) patients underwent tenolysis and were able to achieve postoperative IP flexion of 45° (range: °30-70°). When comparing pre-operative to postoperative active IP-flexion of the patients that underwent tenolysis, this improved by a median of 20° (preoperative: 27.5° (IQR: 10-30) vs. postoperative: 45° (IQR: 45-45) (Table 5).

Table 1.

The Association Between Patient and Injury Characteristics and Active IP-Flexion.

| All patients (n = 57) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Active flexion ROM IP-joint | P value | |

| Age in years, coefficient | −0.29 | .03 a |

| Sex, median (IQR) | .07 b | |

| Female | 40 (20-45) | |

| Male | 30 (20-37.5) | |

| Race, median (IQR)* | .97 b | |

| White | 30 (20-40) | |

| Other | 30 (20-45) | |

| Smoke, median (IQR)** | .88 b | |

| Yes | 30 (20-44) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Diabetes, median (IQR) | .45 b | |

| Yes | 22.5 (10-45) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Worker’s compensation, median (IQR) | .10 b | |

| Yes | 43 (40-60) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Time to surgery in months***, coefficient | 0.02 | .88 a |

| Mechanism of injury, median (IQR) | .17 b | |

| Sharp | 30 (20-45) | |

| Saw | 20 (10-30) | |

| Number of injured digits, median (IQR) | .01 b | |

| Thumb only | 30 (20-45) | |

| > 1 | 10 (10-20) | |

| Dominant hand affected^, median (IQR) | .14 b | |

| Yes | 20 (20-45) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Nerve injury, median (IQR) | .53 b | |

| Yes | 30 (20-45) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Arterial injury, median (IQR) | .28 b | |

| Yes | 20 (10-30) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

Note. ROM = range of motion; IP = interphalangeal; IQR = interquartile range.

Bold= p<0.05.

Spearman’s rank.

Mann-Whitney U-test; *n = 51; **n = 53; ***n = 48; ^n = 52.

Table 2.

The Association Between Surgery Characteristics and Active IP-Flexion.

| All patients (n = 57) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Active flexion ROM in IP-joint | P value | |

| Repair technique, median (IQR)* | .51 a | |

| Kessler | 30 (20-45) | |

| MGH | 35 (20-45) | |

| Other | 20 (15-30) | |

| Number of strands, median (IQR)** | .57 a | |

| 2 | 20 (10-30) | |

| 4 | 30 (20-45) | |

| 6 | 30 (15-40) | |

| Epitendinous suture, median (IQR)*** | .04 b | |

| Yes | 32.5 (20-45) | |

| No | 27.5 (17.5-31.5) | |

| Nerve repair, median (IQR) | .53 b | |

| Yes | 30 (20-45) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Arterial repair, median (IQR) | .16 b | |

| Yes | 20 (10-30) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Suture material, median (IQR)^ | .42 a | |

| Braided | 30 (20-45) | |

| Monofilament | 20 (20-20) | |

| Pulley venting, median (IQR) | .90 b | |

| Yes | 30 (15-45) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

| Tendon retrieval at wrist crease, median (IQR) | .80 b | |

| Yes | 30 (20-45) | |

| No | 30 (20-45) | |

Note. IP = interphalangeal; IQR = interquartile range; ROM = range of motion; MGH = Massachusetts general hospital.

Bold= p<0.05.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Mann-Whitney U-test; *n = 51; **n = 48; ***n = 54; ^n = 45.

Table 5.

Reoperation Details After Direct Zone II FPL Repair.

| Patient | Age | Gender | Race | Mechanism of injury | Number of injured digits | Time to surgery (in days) | Type of reoperation | Indication for reoperation | Time to reoperation (in months) | Active flexion IP-joint before reoperation (in degrees) | Active flexion IP-joint after reoperation (in degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26 | Male | White | Sharp laceration | 1 | 34 | Re-rupture repair | Re-rupture | 0.5 | Missing | Missing |

| 2 | 39 | Male | White | Glass accident | 1 | 1 | Re-rupture repair | Re-rupture | 3.1 | Missing | Missing |

| 3 | 26 | Female | White | Knife accident | 1 | 10 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 1.8 | 30 | 70 |

| 4 | 41 | Male | White | Glass accident | 1 | 0 | Tenolysis | IP-joint stiffness | 5.5 | 10 | 30 |

| 5 | 29 | Male | White | Sharp laceration | 1 | 7 | Granuloma excision | Granuloma | 4.1 | Missing | Missing |

| 6 | 55 | Male | White | Circular saw accident | 1 | 9 | Debridement and skin closure | Closure of lasting open wound | 2.3 | Missing | Missing |

| 7 | 27 | Female | White | Knife accident | 1 | 3 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 5.3 | Missing | 60 |

| 8 | 20 | Male | Other | Knife altercation | 1 | 13 | Re-rupture repair | Re-rupture | 0.43 | Missing | Missing |

| 9 | 34 | Male | White | Knife accident | 1 | 14 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 2.4 | Missing | Missing |

| 10 | 29 | Male | White | Glass accident | 1 | 1 | Re-rupture repair | Re-rupture | 2.4 | Missing | 10 |

| 11 | 71 | Male | White | Glass accident | 1 | 11 | IP-fusion | IP-joint instability | 4.4 | Missing | Missing |

| 12 | 32 | Female | Black | Glass accident | 1 | 2 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 4.4 | 25 | Missing |

| 13 | 44 | Male | White | Circular saw accident | 4 | 0 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 4.8 | Missing | Missing |

| 14 | 25 | Male | White | Glass accident | 1 | 11 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 2.4 | 10 | 45 |

| 15 | 30 | Male | Hispanic | Sharp metal accident | 1 | 7 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 6.5 | 30 | 45 |

| 16 | 54 | Female | Unknown | Knife accident | 1 | 34 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 3.7 | 30 | 45 |

| 17 | 25 | Female | Asian | Knife accident | 1 | 8 | Tenolysis | Adhesion | 3.9 | 25 | 45 |

| 18 | 29 | Male | White | Knife accident | 1 | 6 | Re-rupture repair | Re-rupture | 0.5 | Missing | Missing |

Note. FPL = flexor pollicis longus; IP = interphalangeal.

The reoperation rate was 17% (n = 18) and reoperation occurred at a median of 3.4 months (IQR: 2.3-4.4) after the primary surgery (Figure 1). Indications for reoperation included adhesion formation (n = 10, 56%), re-rupture (n = 5, 28%), IP joint instability (n = 1, 5.6%), granuloma formation (n = 1, 5.6%), or wound healing problems (n = 1, 5.6%) (Table 3). No factors that were statistically associated with reoperation were identified (Table 4). A detailed description of the patients that underwent reoperation is shown in Table 5.

Table 3.

Indications for Reoperation.

| All reoperations (n = 18) | |

|---|---|

| Adhesion, n (%) | 10 (56) |

| Re-rupture, n (%) | 5 (28) |

| IP-joint instability, n (%) | 1 (5.6) |

| Granuloma with abscess formation n (%) | 1 (5.6) |

| Lasting open wound n (%) | 1 (5.6) |

Note. IP = interphalangeal.

Table 4.

The Association Between Patient, Injury and Surgery Characteristics and Reoperation After Direct Zone II FPL Repair.

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 104) | Reoperation |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 18) | No (n = 86) | |||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 34.9 (26.3-48.2) | 29.7 (26.4-41.1) | 38.0 (25.5-48.3) | .50 a |

| Male sex, n (%) | 73 (70) | 13 (18) | 60 (82) | >.99 b |

| Race*, n (%) | >.99 b | |||

| Caucasian | 72 (73) | 13 (18) | 59 (82) | |

| Other | 26 (27) | 4 (15) | 22 (85) | |

| Smoking**, n (%) | 34 (36) | 7 (21) | 27 (79) | .78 b |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 6 (5.8) | 1 (17) | 5 (83) | >.99 b |

| Workers’ compensation, n (%) | 8 (7.7) | 1 (13) | 7 (87) | >.99 b |

| Mechanism of injury, n (%) | .60 b | |||

| Sharp | 83 (80) | 16 (19) | 67 (81) | |

| Saw | 20 (19) | 2 (10) | 18 (90) | |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | |

| Concomitant injury, n (%) | ||||

| Nerve | 67 (64) | 9 (13) | 58 (87) | .18 b |

| Arterial | 11 (11) | 1 (9.1) | 10 (91) | .69 b |

| Dominant hand affected***, n (%) | 31 (36) | 8 (26) | 23 (74) | .25 b |

| Number of injured digits, n (%) | .46 b | |||

| Thumb only | 90 (87) | 17 (19) | 73 (81) | |

| > 1 | 14 (13) | 1 (7.1) | 13 (93) | |

| Repair technique^, n (%) | .90 b | |||

| Kessler | 69 (71) | 10 (14) | 59 (86) | |

| MGH | 14 (14) | 3 (21) | 11 (79) | |

| Other | 14 (14) | 2 (14) | 12 (86) | |

| Epitendinous suture^^, n (%) | 55 (55) | 10 (18) | 45 (82) | .79 b |

| Number of strands^^^, n (%) | .87 b | |||

| 2 | 5 (5.7) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | |

| 4 | 72 (82) | 14 (19) | 58 (81) | |

| 6 | 11 (13) | 1 (9.1) | 10 (91) | |

| Suture material, n (%)ˣ | >.99 b | |||

| Braided | 79 (91) | 15 (19) | 64 (81) | |

| Monofilament | 8 (9.2) | 1 (13) | 7 (87) | |

| Concomitant repair, n (%) | ||||

| Nerve | 67 (64) | 9 (13) | 58 (87) | .18 b |

| Arterial | 7 (6.7) | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | >.99 b |

| Pulley venting, n (%)ˣˣ | 24 (24) | 3 (13) | 21 (87) | .76 b |

| Proximal incision, n (%) | 32 (31) | 7 (22) | 25 (78) | .41 b |

Note. FPL = flexor pollicis longus; IQR = interquartile range; MGH = Massachusetts general hospital.

Mann-Whitney U-test.

Fisher’s exact test; *n = 98; **n = 94; ***n = 87; ^n = 97; ^^n = 100; ^^^n = 88; ˣn = 97; ˣˣn = 102.

Stiffness was the most common complication (n = 27, 26%) of which 10 patients (37%) underwent reoperation. Other complications included diminished sensation (n = 18, 17%), a contracture of the first web space (n = 2, 1.9%), cold intolerance (n = 1, 0.96%), infection (n = 1, 0.96%), neuroma (n = 1, 0.96%), paresthesias (n = 1, 0.96%), a positive Tinel’s sign (n = 1, 0.96%), seroma (n = 1, 0.96%), trigger thumb (n = 1, 0.96%), and wound healing problems (n = 1, 0.96%) (Table 6). There were no clinical re-ruptures that did not undergo revision surgery.

Table 6.

Complications After Zone II FPL Repair.

| Complication | All patients (n = 104) | Reoperation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 18) | No (n = 86) | ||

| Stiffness, n (%) | 27 (26) | 10 (37) | 17 (63) |

| Diminished sensation, n (%) | 18 (17) | 0 (0) | 18 (100) |

| First webspace contracture, n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Cold intolerance, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Infection, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Neuroma, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Paresthesias, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Positive Tinel’s sign, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Seroma, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Trigger thumb, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Wound healing problems, n (%) | 1 (0.96) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

Note. FPL = flexor pollicis longus.

Discussion

Following Zone II FPL repair, the final median active IP-flexion was 30 degrees (IQR: 20-45) at a median of 12.4 weeks. Older age and having multiple injured digits were associated with less IP-flexion, whereas the use of an epitendinous suture was associated with increased active IP-flexion (32.5 degrees vs. 27.5 degrees). The reoperation rate was 17% and adhesion formation (9.6%) and re-rupture (4.8%) were the most common indication for reoperation. Postoperative complications mainly included stiffness or diminished sensation.

The results of this study should be interpreted in context of its limitations. First, this was a retrospective study relying on correct coding. We tried to mitigate this error through manual chart review. Second, there were missing data for the IP-flexion in 45% of the total cohort, therefore only 55% of the total cohort was included in the IP-flexion analysis. However, the patient groups with and without available IP-flexion data were comparable in demographics and injury characteristics and can therefore be considered representative (Supplemental Appendix 2). IP flexion data regarding the contralateral thumb were not reported in most of the medical charts. Additionally, ROM measurements were not reported at each final clinical visit and were last measured at a median of 12.4 weeks (IQR: 8.1-16.7) postoperatively, despite the longer median follow-up time of 2.1 years (IQR: 0.30-7.4). Furthermore, the decision to perform reoperation is a clinical decision made at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Multiple factors, including compliance with occupational therapy, may influence the decision to perform reoperation. Lastly, as we specifically focused on FPL injuries in Zone II only, the final number of included patients was relatively small. This may have led to an insufficient power to detect factors that may be associated with reoperation in a larger cohort.

Previous animal and in vitro studies have shown the benefits of an epitendinous suture related to the functional outcome after flexor tendon repair.9,10 After repair, the quality of tendon gliding depends on multiple factors including the degree of tendon gapping, bulkiness and exposure of suture material at the repair site. 11 By reducing tendon gap formation9,12 and smoothening the tendon stumps, 1 epitendinous sutures improve the quality of tendon gliding after repair leading to greater ranges of motion. Furthermore, multiple animal/ biomechanical analyses9,12 as well as cadaveric studies 10 demonstrate that the addition of an epitendinous suture increases the tensile strength. Even though most studies encourage the use of epitendinous sutures, others suggest they are unnecessary when used accompanying a strong multistrand core suture. 1 Other studies suggest that additional epitendinous suture may lead to greater bulk at the repair site along with an increased inflammatory response increasing the risk of adhesion formation.13,14 However, these findings are not consistent among all studies. 15 Our clinical data are in line with studies supporting epitendinous suture, as greater IP motion implies fewer adhesions.

In this study, active IP-flexion was reduced when multiple digits were injured. A previous clinical study by Starnes et al 8 reported that in patients who had more severe injuries with multiple injured digits, concomitant arterial injury, and concomitant nerve injury, the postoperative range of motion was reduced. Usually in injuries involving multiple digits, the larger zone of injury limits rehabilitation.

To conclude, about 1 in 5 patients undergo reoperation following primary direct repair of a Zone II FPL laceration, mostly within 6 months of initial surgery. Our data provide a clinical correlation to prior animal and biomechanical studies supporting epitendinous repair.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, appendix1_and_2a_and_b for Zone II Flexor Pollicis Longus Repair: Thumb Flexion and Complications by Luca L. Bruin, Jonathan Lans, Kyle R. Eberlin and Neal C. Chen in HAND

Supplemental material, supplemental_figure1 for Zone II Flexor Pollicis Longus Repair: Thumb Flexion and Complications by Luca L. Bruin, Jonathan Lans, Kyle R. Eberlin and Neal C. Chen in HAND

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available in the online version of the article.

Author Contributions: Study design was by L.L.B., J.L., and N.C/C.; data assembly was done by L.L.B. and J.L.; data analysis was performed by L.L.B., J.L., and N.C.C.; and initial drafting was by L.L.B., J.L., K.R.E., and N.C.C.; and final approval of the manuscript was by L.L.B., J.L., K.R.E., and NCC

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained when necessary.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: L.L.B. and J.L. declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. N.C.C. is a consultant for Flexion Medical, Miami Device Solutions and a lecturer for DePuy Synthes. KRE is a consultant for AxoGen and Integra.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Luca L. Bruin  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5680-0344

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5680-0344

Jonathan Lans  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6159-4645

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6159-4645

Kyle R. Eberlin  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5397-8147

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5397-8147

Neal C. Chen  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7527-1110

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7527-1110

References

- 1. Tang JB. Flexor tendon injuries. Clin Plast Surg. Jul. 2019;46(3):295-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pan ZJ, Qin J, Zhou X, et al. Robust thumb flexor tendon repairs with a six-strand M-Tang method, pulley venting, and early active motion. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2017;42(9):909-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rappaport PO, Thoreson AR, Yang TH, et al. Effect of wrist and interphalangeal thumb movement on zone T2 flexor pollicis longus tendon tension in a human cadaver model. J Hand Ther. 2015;28(4):347-354; quiz 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edsfeldt S, Eklund M, Wiig M. Prognostic factors for digital range of motion after intrasynovial flexor tendon injury and repair: long-term follow-up on 273 patients treated with active extension-passive flexion with rubber bands. J Hand Ther. 2019;32(3):328-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dy CJ, Hernandez-Soria A, Ma Y, et al. Complications after flexor tendon repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(3):543-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoffmann GL, Buchler U, Vogelin E. Clinical results of flexor tendon repair in zone II using a six-strand double-loop technique compared with a two-strand technique. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33(4):418-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dy CJ, Daluiski A, Do HT, et al. The epidemiology of reoperation after flexor tendon repair. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(5):919-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Starnes T, Saunders RJ, Means KR., Jr. Clinical outcomes of zone II flexor tendon repair depending on mechanism of injury. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(12):2532-2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Putterman AB, Duffy DJ, Kersh ME, et al. Effect of a continuous epitendinous suture as adjunct to three-loop pulley and locking-loop patterns for flexor tendon repair in a canine model. Vet Surg. 2019;48(7):1229-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diao E, Hariharan JS, Soejima O, et al. Effect of peripheral suture depth on strength of tendon repairs. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(2):234-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mehling IM, Arsalan-Werner A, Sauerbier M. Evidence-based flexor tendon repair. Clin Plast Surg. 2014;41:513-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cocca CJ, Duffy DJ, Kersh ME, et al. Biomechanical comparison of three epitendinous suture patterns as adjuncts to a core locking loop suture for repair of canine flexor tendon injuries. Vet Surg. 2019;48(7):1245-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanders DW, Milne AD, Johnson JA, et al. The effect of flexor tendon repair bulk on tendon gliding during simulated active motion: an in vitro comparison of two-strand and six-strand techniques. J Hand Surg Am. 2001;26(5):833-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wichelhaus A, Beyersdoerfer ST, Vollmar B, et al. Four-strand core suture improves flexor tendon repair compared to two-strand technique in a rabbit model. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4063137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Strick MJ, Filan SL, Hile M, et al. Adhesion formation after flexor tendon repair: comparison of two- and four-strand repair without epitendinous suture. Hand Surg. 2005;10(2-3):193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, appendix1_and_2a_and_b for Zone II Flexor Pollicis Longus Repair: Thumb Flexion and Complications by Luca L. Bruin, Jonathan Lans, Kyle R. Eberlin and Neal C. Chen in HAND

Supplemental material, supplemental_figure1 for Zone II Flexor Pollicis Longus Repair: Thumb Flexion and Complications by Luca L. Bruin, Jonathan Lans, Kyle R. Eberlin and Neal C. Chen in HAND