Abstract

Introduction

Social isolation is detrimental to late-life health outcomes. Although objective social isolation is a major source of perceived loneliness, how different layers of social disconnection systematically constitute the subjective experience of loneliness remains unclear.

Methods

This study focused on older adults who participated in the Korean Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (KSHAP) (n = 1,724; mean age = 72.91 years) and examined how the proximal and distal characteristics of social networks predict loneliness using a hierarchical linear regression model. The study also investigated whether the major loss of social roles (marital and working status) influences perceived loneliness through the proximal and distal aspects of social networks by cross-sectional mediation analysis.

Results

This study found that the proximal (subjective number of connections) and distal (brokerage and embeddedness) aspects of social networks additively explained the frequency of loneliness. Moreover, the loss of late-life social roles (marital and working status) was related to an increase in loneliness, where the distal characteristic of social networks mediated this relationship.

Discussion/Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that the proximal and the distal characteristic of social networks is a social determinant predicting loneliness in late life. Besides, the loss of bridging and cohesive position among community networks may be a critical pathway to psychosocial transition after marital and working status changes.

Keywords: Loneliness, Social network analysis, Marital status, Retirement

Introduction

Evidence suggests that social isolation is detrimental to health. Objective and subjective forms of social disconnectedness are associated with low physical well-being and high mortality rates equivalent to or more significant than other well-known risk factors [1]. Moreover, interest in maintaining an integrated social life increases as older adults experience transition in social life after retirement. The consequence of social disconnection may become increasingly profound with age-related deterioration of health conditions [2]. Previous studies have shown that perceived loneliness increases cardiovascular disease risks [3] and cognitive impairment [4].

Although loneliness is a subjective experience, perceived loneliness is composed of both subjective experience and objective disconnections [5]. The objective social disconnection is categorized across different levels, from proximal to distal levels. For instance, the collective aspect of loneliness, which is associated with group identification and cohesion, can be distinguished from the relational part of loneliness characterized by a feeling of familiarity, closeness, and support [6]. Notably, both disconnections in the personal and collective space can engender feelings of loneliness by triggering a social alarm system [7]. Accordingly, many studies have shown that one's perception of the neighborhood is associated with cardiovascular health risks even when controlling for various psychosocial factors. This result indicates that the distal level of social disconnection also plays an important role in its detrimental effects on psychological and physical outcomes [8].

To date, numerous studies on the relationship between social disconnection and loneliness primarily focused on the proximal aspects of social networks. Although several studies focused on the distal aspect of social networks, most existing approaches mainly rely on rating feelings of collective connectedness (“I feel part of a group of friends,” and “I really feel part of this area”) or assess the number of social relationships with respondent-centered methods due to a practical limitation in examining the outermost layer of social disconnection beyond one's personal space [9]. The operational definition and objective measurement of such disconnectedness has been a challenging issue.

Such methodological challenges can be partly resolved by mapping complete social connections and utilizing social network analysis [10, 11]. Although individual-level measures indicate one's perception of a proximal social connectedness, social network analysis provides distal social connectedness from a globally mapped social network by assessing a social network position or location within a larger community. In contrast to information from respondent-centered social relationships, the global network approach assesses the structural properties of social connectedness. It relies less on endogenous personal factors while reflecting one's distal social network characteristics.

Among various global social network properties, 2 major indicators, namely, brokerage and embeddedness, depict whether an individual can benefit by connecting with diverse network members or staying within a cohesive network group. Such structural characteristics of social networks may represent the outmost layer of one's social network that shapes an individual's loneliness. There is no study that has investigated a direct association between the global social network properties and loneliness yet. However, evidence that emotional loneliness, which is derived from the loss of social connection, is hazardous to health suggests that the distal social disconnection may also affect loneliness and health [3]. In fact, the brokerage position was associated with better cognitive and physical health [12, 13]. Also, it has been known that enough affiliations within cohesive relationships (embeddedness) can benefit an individual with reliable and stable social support via facilitated trust and collaboration [11].

The fact that older adults inevitably undergo significant transitions in the size and composition of social networks raises concern on older adults' mental and physical health [14]. The convoy model suggests that social connections surrounding individuals are frequently embedded within the social convoy context. Late-life situational factors can influence various aspects of social networks [15]. The literature suggested that external social events operate through proximal factors to influence loneliness, where major changes in social roles are crucially associated with late-life loneliness [16]. It is mostly unknown how the external aspects of life events, such as marital status change and retirement, reorganize the size, strength, and structural characteristics of social networks.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the impact of proximal and distal social disconnections on perceived loneliness. The current study examined whether older adults with limited brokerage opportunities and less embedded positions are more likely to experience loneliness. Furthermore, the study hypothesized that low levels of integrity in terms of global characteristics of social networks (brokerage and embeddedness) are associated with higher levels of loneliness even when accounting for the primary sociodemographic, health, and respondent-centered attributes of the social network. By using a cross-validation, the study examined whether the predictors of social networks' global measures (brokerage and embeddedness) can enhance accuracy in predicting loneliness. Additionally, the study scrutinized the association among social roles (marital and working status), proximal to distal social network characteristics, and loneliness using a cross-sectional mediation model. Last, the study hypothesized that the effect of marital and working status on loneliness is mediated by the respondent-centered characteristics of social networks and the global integrity of social networks' features, representing proximal to distal social network characteristics, respectively.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study used data from the Korean Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (KSHAP), which was conducted in 2 rural towns in South Korea, namely, townships K and L. Initially, 841 (township K) and 948 (township L) participants aged 60 years or older and their spouses were administered a social network survey to collect comprehensive data on social networks [17]. Interviews were conducted in the respondents' homes or at community centers. Incomplete health or social network surveys were excluded, which rendered 1,724 valid surveys for analyses (Table 1). Chronological age ranged from 42 to 100 years (mean = 72.91; SD = 7.69). The total years of residence in the township showed a wide range of variability from a few months to 94 years (mean = 47.47; SD = 26.17). The study was approved by and performed in accordance with the relevant the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University's relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants were fully informed and provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| All participants (n = 1,724) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, n (%) | |

| <60 | 349 (20.2) |

| 60–69 | 788 (45.7) |

| 70–79 | 535 (31.0) |

| 80 + | 52 (3.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 1,000 (58.0) |

| Male | 724 (42.0) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| No schooling | 472 (27.3) |

| Elementary school | 739 (42.9) |

| Middle school | 256 (14.8) |

| High school | 185 (10.7) |

| University + | 72 (4.2) |

| Currently working, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1,218 (70.6) |

| No | 506 (29.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Living with spouse | 1,290 (74.8) |

| Not living with spouse | 434 (25.2) |

| Chronic illness (presence), n (%) | |

| Diabetes | 300 (17.4) |

| Coronary heart disease | 94 (5.4) |

| Arthritis | 559 (32.4) |

| Stoke | 64 (3.7) |

| Cancer | 68 (3.9) |

| Self-rated health, n (%) | |

| Excellent | 28 (1.6) |

| Very good | 195 (11.3) |

| Fair | 839 (48.7) |

| Somewhat poor | 525 (30.4) |

| Poor | 137 (7.9) |

| Perceived loneliness, n (%) | |

| Rarely (<1 days per week) | 1,223 (70.9) |

| Sometimes (1–2 days per week) | 376 (21.8) |

| Occasionally (3–4 days per week) | 97 (5.6) |

| Mostly (5–7 days per week) | 28 (1.6) |

Social Network Construction

The social network variables were created using data from the KSHAP, which adopted a name generator from the General Social Survey and National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project [17, 18]. Social connections were constructed from the name generator that identifies social network members, such as a spouse, if any, and up to 5 discussion partners and their real names, gender, and residence. The following question was presented: “from time to time, most people discuss things that are important to them with others. For example, good or bad things that happen to you, problems you are having, or important concerns you may have. Looking back over the last 12 months, who are the people with whom you most often discussed things that were important to you?” In this study, we asked the participants to report the name of their discussion partners up to 5 people based on empirical evidence suggesting that individuals can report 5 discussion partners without significant report bias [19]. In the name generator, we limited the discussion members up to 5 people, in order to acquire additional questionnaires about each discussion members.

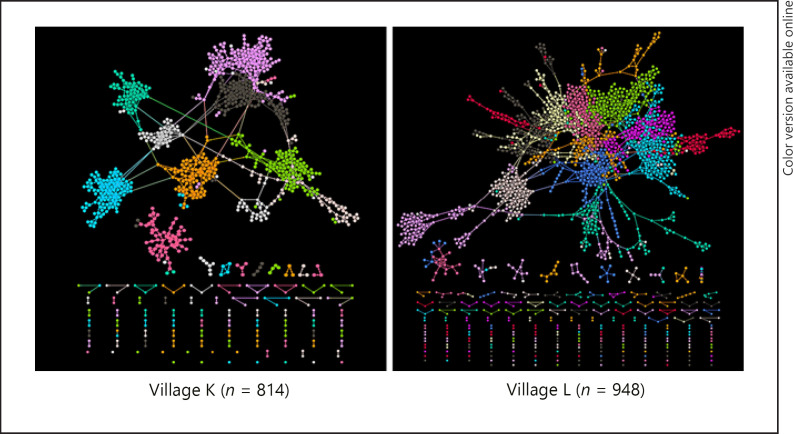

To establish each respondent-centered network as a complete network of township K, people who appeared in the networks of different respondents were identified the same based on the following criteria (1) approximately 2 out of 3 Korean characters in their names match; (2) same gender; (3) age difference of fewer than 5 years; and (4) addresses belonged to the same Ri (the smallest administration unit in South Korea). Those who were not spouses of respondents and lived outside of the township were excluded. Finally, the study identified an extensive network of the township residents and their ties (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Complete social network of townships K and L. Different colors represent different Ri (smallest administration unit).

Characteristics of Personal Social Networks

The study assessed the strength of personal and social connections using the frequency of communication and intimacy within one's discussion members (constructed with a name generator of up to 5 and a spouse, if any). To measure intimacy, the interviewer posed the following question about each member of the social connections: “How close do you consider your relationship with (the network member)?” Respondents selected from 4 possible answers, namely, “not very close,” “slightly close,” “very close,” and “extremely close.” Each answer was coded as an integer from 1 to 4 and averaged across all connections. Communication was measured by rating its frequency as “every day,” “several times a week,” “once a week,” “once every 2 weeks,” “once a month,” “several times a year,” and “less than once a year.” Each answer was coded as an integer from 1 to 8 and averaged across all connections. The following question was used to assess the subjective size of social networks: “Looking back over the last 12 months, how many people did you often discuss things that are important to you?” before constructing individual discussion partners. Although this question is for subjective social network size, it is very similar to the question used for the name generator. The subjective social network size question allows the participants to report >5 discussion partners without providing discussion partner's information, such as their discussion partner's name or address. To adjust a realistic estimate of one's network size, we assigned a maximum of 15 members (3.3%, n = 57) into a sympathy group [20] and adjusted the positive skewness (unadjusted skewness = 18.14; adjusted skewness = 1.80). Thus, the subjective network size ranged from 0 to 15 (adjusted) (mean = 4.29; SD = 3.49).

Global Characteristics of Social Networks

Brokerage

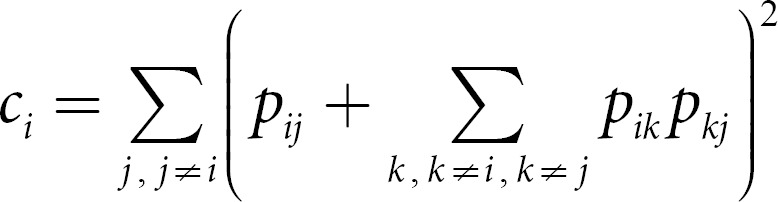

Brokerage indicates a social network position connecting the unconnected others. Previous research investigating the characteristics of brokerage has utilized network constraint to represent the brokerage opportunity of an individual [21]. The network constraint is an inverse measure of brokerage (a smaller value of network constraint indicates more opportunity for brokerage). In other words, the network constraint conceptually refers to how much room an individual has to exploit a potential gap between 2 individuals.

To explain network constraint, let us assume that there are 3 people: person i, person j, and their mutual friend k. The person i is constrained by j as much as (1) the person i invests time and resources into a relationship with j, and (2) i maintains a relationship with k, who has a relationship with j.

In terms of person i, if j accounts for most relationships of the person i has and the other relationship than j, such as k, is also linked to j, i has no opportunity to connect j with others who are unconnected with j. In other words, i is highly constrained in the relationship with j with low brokerage opportunity. An individual's structural constraint increases if an individual's network member is connected with those holding a high proportional connection with the overlapping network members. The following equation was used to calculate the person i's social network constraint within his/her global social network.

In the equation, Pij corresponds to the proportion of i's direct social ties accounted for by his/her tie to actor j. The inner summation approximates the indirect constraint imposed on i by another person, k, who is socially connected to both i and j (mutual friends of i and j). An unweighted, undirected graph was used to estimate constraint, that is, the presence of any social tie, irrespective of its direction, was used to compute the constraint of each node [21].

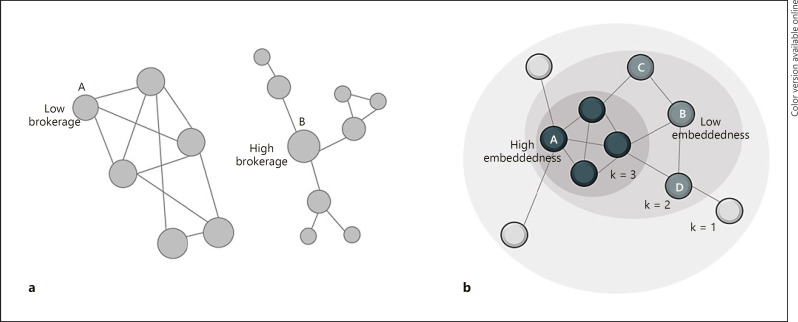

Figure 2a illustrates that individual A has ties with people connected to one another (highly constrained network). In contrast with A, B maintains a relationship with others not connected to one another (A's constraint = 0.75; B's constraint = 0.3). Although A and B have the same number of connections, B presumably has more brokerage potential and benefits from fewer constraints. The participants' structural constraints ranged from 0.08 to 1.14 (mean = 0.56; SD = 0.31). In the absence of calculable structural constraints, participants without social ties within the global social network were excluded from analyses (n = 14).

Fig. 2.

Schematics of global characteristics of social networks. a Example of brokerage position. b has a better opportunity for the bridging role and smaller network constraint than a. In contrast with a, b maintains a relationship with others who are not connected to one another. b Example of structural embeddedness. An individual connected with people who have at least k social connections belongs to the k-core group. Although the number of social connections for a and b is the same (n = 3), only a can be a member of the 3-core group and has a higher k-core score than b (3 vs. 2).

Embeddedness

The k-core score was used to measure structural embeddedness and cohesiveness of an individual's social network position [40]. A k-core group is composed of people with approximately k social connections with others in the same group. This subgraph is unique and can be extracted by iteratively pruning nodes with degrees less than k. For a network of interacting nodes, the k-core pertains to the portion of the network that remains after iteratively removing all nodes linked to <k other nodes from the network [22]. Thus, one takes the highest value of k as the k-core score because one can belong to several nested k-core groups from low k to high k. For example, A in Figure 2b belongs to the 3 types of k-core groups (a 1-core group composed of all 10 people in the graph, a 2-core group of 7 people, and a 3-core group of 4 people). Thus, the k-core score for A is 3, which corresponds to the maximum of k. Conversely, the k-core score for B is 2 because B is a nonmember of the 3-core group. Although B has the same size as A, B cannot hold 3 social connections when C and D (having only 2 social connections in the 2-core group) are excluded from the 3-core group. Compared with B, A is more likely to belong to the core of the social groups and thus deeply embedded in people's networks. The k-core score of the participants ranged from 0 to 5 (mean = 2.33; SD = 0.10).

Loneliness

The study measured perceived loneliness using the single item “I felt lonely as if I were left alone in the world” of the Korean version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [23, 24]. This item asks respondents whether they felt generally lonely over the past week. Four categorized responses (“less than a day,” “1–2 days,” “3–4 days,” and “5–7 days”) were used as continuous outcome variables. Although CES-D is a commonly used scale to assess depressive symptoms in population studies, previous factor analyses have indicated the discriminant validity of the single loneliness item (“I felt lonely”) [25]. The identical question was utilized in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), which is a population-based longitudinal study [26]. In the FHS cohort, the mean number of days feeling lonely per week was 0.85 ± 0.96 (mean age = 63.78 ± 11.85) days. In KSHAP, the mean number of days feeling lonely per week was 0.97 ± 0.99 (mean age = 72.91 ± 7.69) days.

Social Roles

Marital status was binary-coded according to whether one is living with or without a spouse. The reasons for not living with a spouse were the following. Bereavement (93.1%, n = 406), divorced (3.7%, n = 16), separation (1.8%, n = 8), and unmarried (1.4%, n = 6). Working status was binary-coded according to whether the respondents were employed or unemployed. The majority of working participants were involved in farming (88%; n = 1,072) followed by other categories (service industry: 2.7%, n = 34; private business: 2.1%, n = 26; family work: 1.8%, n = 23; and clerical work: 1.1%, n = 13).

Covariates

The study assessed potential covariates that account for or confound the association between the characteristics of social networks and perceived loneliness. The participants rated the level of global health on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: 5 = poor, 4 = slightly poor, 3 = good, 2 = very good, and 1 = excellent; the higher the values, the poorer the self-rated health. The interviewers also instructed the respondents to indicate whether they received a clinical diagnosis of diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and cancer. The study assessed the objective health condition using the total number of diagnosed chronic illnesses. In the multiple regression model, age, sex, formal education level (no schooling, elementary school or traditional school, middle school, and high school or higher), self-rated health, objective health condition, marital status, and working status were included as covariates. In mediation analysis, marital and working statuses were modeled as major independent variables, whereas the aforementioned demographics and health were equally included as covariates. Last, we adapted the ability to function of daily activity as a covariate considering that functional status may limit individuals' social resources. The daily activity level was evaluated using the Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) Scale [27]. Eight items from the K-IADL were used: light tasks around the house, preparing meals, doing laundry, using transportation, shopping, managing money, using the telephone, and taking medication. The K-IADL score ranged from 0 to 8, and the lower scores indicated higher instrumental activity levels.

Statistical Analysis

Hierarchical Regression Analysis

The study conducted hierarchical linear regression to examine whether the characteristics of social networks additionally explain perceived loneliness. The primary model (model 1) consisted of rudimentary sociodemographic (age, education, sex, working status, years of residence, and marital status) and health factors (chronic illnesses and self-rated health). Model 2 added respondent-centered characteristics of social networks, such as subjective network size and strength of social connections. Model 3 added 2 social network measures derived from the global network, namely, brokerage and embeddedness. Although we considered the function of daily activity as a covariate, due to the limited availability of the function of daily activity, which is collected only in township L, n = 948), we conducted a supplementary analysis using the subsampled participants from township L (n = 948). In the supplementary analysis, we tested whether our findings are significant after adjustment for the measure of daily function by adding the covariate representing the function of daily activity to the final model (model 3).

The study tested the χ2 difference between models 1 and 2 and between models 2 and 3. Introducing multiple numbers of predictors can overfit the given data. Thus, the study used 10-fold cross-validation to obtain an unbiased estimate of the predictive accuracy of each hierarchical model. Next, whether the additional predictors from models 1 to 3 led to high predictive accuracy (Spearman's rank correlation and mean absolute error) across the 10-fold cross-validation was examined. The proposed framework attempts to establish the relationship between loneliness and multiple social network levels in a stepwise manner using hierarchical regression. Thus, the research intends to propose a comprehensive framework with the relationship between multiple social network layers and understand their influence on perceived loneliness.

Mediation Analysis

To explore social relationship factors leading to perceived loneliness, the study investigated whether the specific characteristics of the social network mediate the effect of late-life major social roles (marital status and working status) on loneliness. High collinearity was noted between the 2 measures of global social network characteristics (embeddedness and brokerage). Thus, a common principal component variance was extracted and summarized as a composite score with equal weights (77.1% of the common variance explained). The composite score of the global social network and 3 personal social network indicators, namely, communication frequency, intimacy, and subjective network size, were introduced into the paralleled mediation model. The study used PROCESS 2.16 macro for SPSS [28] to produce indirect mediation effects. Paralleled mediation models tested for indirect effects and simultaneously controlled for age, education, sex, years of residence, chronic illnesses, and self-rated health. The bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) of the indirect effects were determined by stratified bootstrap resampling (n = 5,000). Indirect effects with 95% CIs not encompassing zero were accepted as significant mediation effects. Additionally, Sobel's test statistics and the ratio of indirect to the total effect of mediators were calculated.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

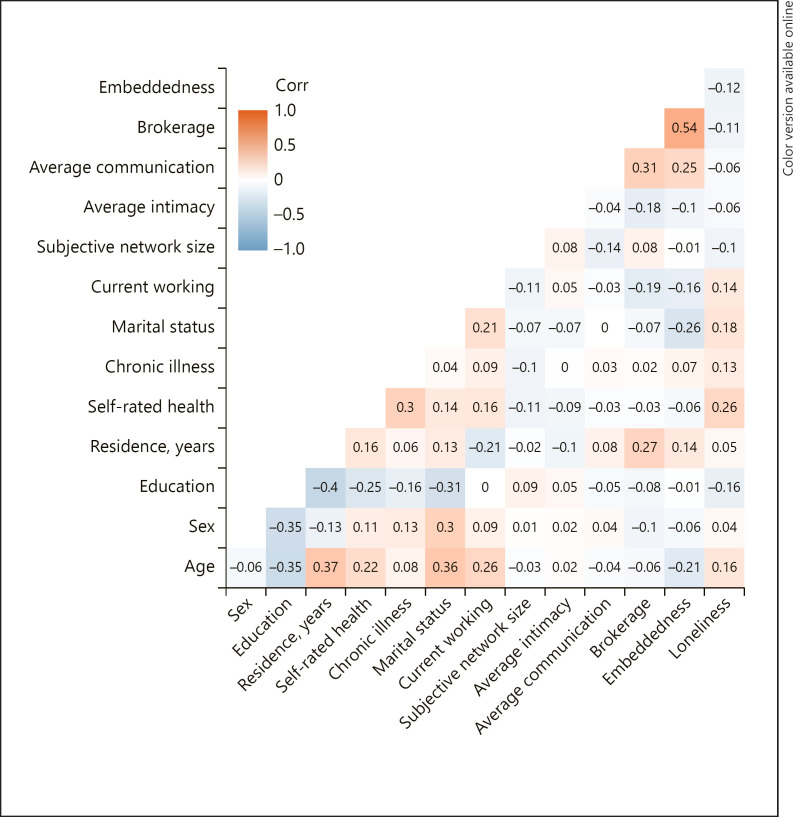

In the pairwise correlational analysis, 2 measures of global social network characteristics indicated a high correlation with average communication frequency and total years of residence (Fig. 3). Brokerage and embeddedness showed a high positive correlation due to the shared basis of the total number of ties in the township. The subjective size of social connections was moderately correlated with a high frequency of communication and brokerage.

Fig. 3.

Pearson's correlation coefficient between demographic, health, and social network predictors. Marital status: 0 = living with spouse; 1 = not living with spouse. Working status: 0 = currently working; 1 = not working. High self-rated health indicates poor status.

Stepwise Hierarchical Regression Model

Three stepwise models were compared in hierarchical linear regression analysis (Table 2). The first model (model 1) showed that older adults with better health, ongoing occupation, and living with a spouse reported low loneliness levels. In the following models examining the effect of proximal to distal social network characteristics in predicting loneliness, personal and global social network characteristics provided an additive explanation on the frequency of loneliness among older adults. Older adults positioned at the high possibility of brokerage indicated low levels of loneliness. The effects of communication frequency, marital status, and working status observed in model 2 revealed a relative decrease with the introduction of global social network measures. This finding indicates shared predictive information between structural position and other predictors of social relationships. Adding the predictors of social network characteristics explained the added variance of loneliness (model 1/2: R2 change = 0.006, p = 0.004; model 2/3: R2 change = 0.007, p = 0.003). In model 3, the collinearity statistics of the variance inflation factor ranged from 1.09 (average intimacy) to 1.66 (network constraint).

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear regression model predicting loneliness

| Model 1 (without social network) |

Model 2 (with personal social network) |

Model 3 (with global social network) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | p value | B | 95% CI | p value | B | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age, years | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.01 | 0.296 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.01 | 0.254 | 0.00 | −0.00 to 0.01 | 0.547 |

| Sex | −0.09 | −0.16 to −0.02 | 0.012 | −0.08 | −0.15 to −0.01 | 0.032 | −0.09 | −0.16 to −0.02 | 0.017 |

| Education | −0.06 | −0.09 to −0.02 | 0.002 | −0.05 | −0.09 to −0.02 | 0.003 | −0.06 | −0.09 to −0.02 | 0.001 |

| Years of residence | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | 0.159 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | 0.215 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | 0.650 |

| Self-rated health | 0.16 | 0.12 to 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.11 to 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.11 to 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Chronic illness | 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.09 | 0.019 | 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.09 | 0.023 | 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.10 | 0.013 |

| Marital status | 0.18 | 0.11 to 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.09 to 0.25 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.08 to 0.24 | <0.001 |

| Currently working | 0.10 | 0.03 to 0.18 | 0.007 | 0.10 | 0.02 to 0.17 | 0.011 | 0.09 | 0.02 to 0.16 | 0.017 |

| Subjective network size | −0.01 | −0.02 to 0.00 | 0.009 | −0.01 | −0.02 to 0.00 | 0.028 | |||

| Average intimacy | −0.03 | −0.08 to 0.02 | 0.195 | −0.05 | −0.10 to 0.00 | 0.072 | |||

| Average communication frequency | −0.04 | −0.07 to −0.01 | 0.008 | −0.02 | −0.05 to 0.01 | 0.144 | |||

| Brokerage (structural constraint) | −0.14 | 0.02 to 0.27 | 0.026 | ||||||

| Embeddedness (k-core) | −0.02 | −0.06 to 0.02 | 0.261 | ||||||

CI, confidence interval.

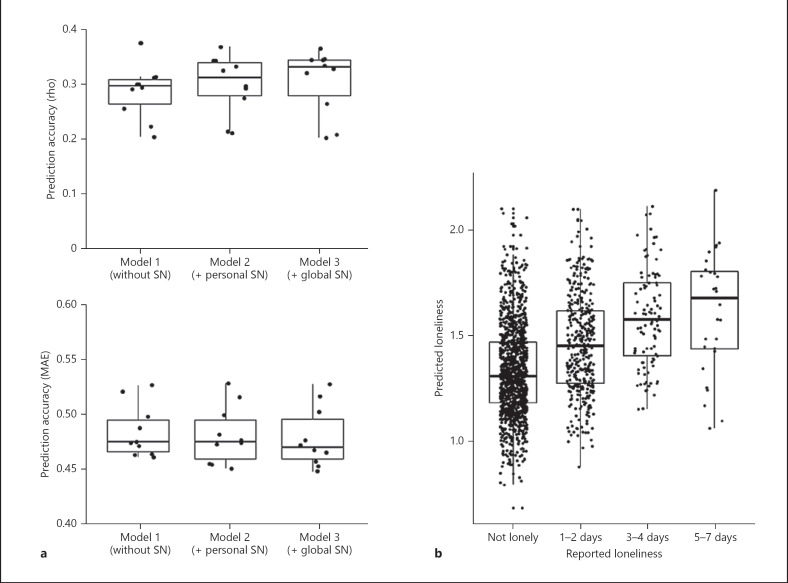

To assess increased predictive accuracy when combining the characteristics of social networks in predicting loneliness, the study conducted 10-fold cross-validation. The correlation between predicted and actual loneliness in a social network showed a moderate increase from 0.287 to 0.306 (Spearman's rho) with the addition of the personal and global predictors of social networks (Fig. 4a). Results ranged from rho = 0.20 to 0.37 across 10-folds. In addition, the error metrics between predicted and actual loneliness highlighted a moderate decrease from 0.484 to 0.479 (mean absolute error) with the introduction of social network predictors. In the final model (model 3 + personal and global measures of social networks), the value for predicted loneliness moderately tracked actual loneliness in novel individuals (rho = 0.30 and mean absolute error = 0.480) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Prediction result of cross-validation of loneliness. a Comparison of predictive accuracy (Spearman's rank correlation and mean absolute error) between predicted and actual loneliness across 3 linear regression models. Each dot denotes predicted results of the 10-times folded test dataset. Three models were composed of hierarchically added predictors (model 1 = demographics + health condition + marital status + work, model 2 = model 1 + personal social network characteristics, and model 3 = model 2 + global social network characteristics). b 10-fold cross-validated prediction result of model 3. The predicted values of the actual report of loneliness (CES-D item 14) and model-predicted loneliness are plotted. Reported loneliness was coded from 1 to 4. CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

To describe the result of supplementary analysis, including the function of daily activity as a covariate in the final model (model 3) using the subsample (n = 948), no personal social network variables were significant in the prediction of loneliness. However, the brokerage variable as a global social network measure significantly predicted loneliness (B = −0.192, p = 0.021) in the model accounting for the function of daily activity. However, embeddedness was not significant in this model (B = −0.008, p = 0.78).

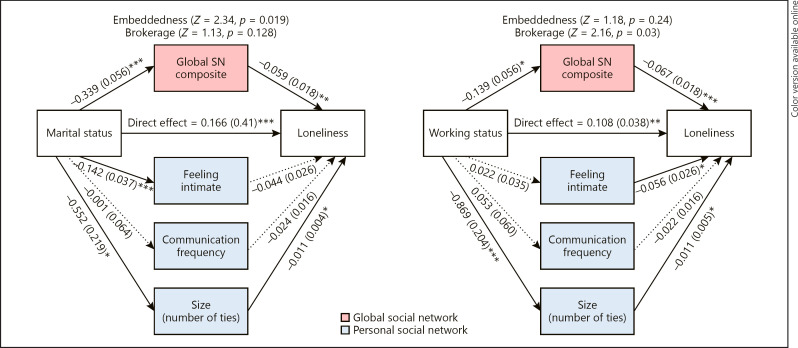

Cross-Sectional Mediation Model

The study examined the role of proximal to distal social networks in the relationship between a social role (working and marital status) and loneliness. The 2 cross-sectional mediation models specifically explored whether personal or global social network measures mediate the effect of marital status or working status. Older adults who do not live with spouses showed high levels of perceived loneliness, and global social network composite and a subjective number of social relationships mediated such a relationship (Fig. 5). In other words, marital status (mostly due to widowhood) was associated with loneliness, as evidenced by a small subjective number of social connections, and decreased structural integrity within the entire township. Although marital status was associated with average intimacy among social relationships, this effect did not lead to loneliness.

Fig. 5.

Parallel mediation path model of the personal and global characteristics of the social network. Coefficient (standard error) and p values of the regression coefficients are indicated. Effects of age, education, sex, and years of residence, chronic illnesses, and self-rated health were controlled. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

The study observed a similar mediating relationship between working status and loneliness. Older adults maintaining a working status showed low levels of loneliness. The subjective number of social connections and structural integrity within the social network mediated the effect of working status on perceived loneliness (Fig. 5). Comparing the indirect effects of mediators, the global characteristics of the social network indicated a relatively substantial mediating effect in explaining perceived loneliness (Table 3). The 95% CIs of the indirect effects of the structural integrity in the global social network and subjective network size did not encompass zero, thus indicating significant mediating effects.

Table 3.

Indirect effect of mediators (global and personal social network characteristics)

| Beta (CI) | Indirect/total effect ratio | Sobel test |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | p value | |||

| (A) Marital status → social network → loneliness Global SN composite | 0.020 (0.008, 0.038) | 0.10 | 2.86 | 0.005 |

| Personal SN | ||||

| Feeling intimate | 0.006 (−0.001, 0.018) | 0.03 | 1.50 | 0.134 |

| Communication frequency | 0.000 (−0.004, 0.005) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.993 |

| Size (subjective) | 0.006 (0.001, 0.015) | 0.03 | 1.72 | 0.086 |

|

| ||||

| (B) Working status → social network → loneliness Global SN composite | 0.009 (0.002, −0.022) | 0.07 | 2.06 | 0.040 |

| Personal SN | ||||

| Feeling intimate | −0.001 (−0.008, 0.002) | −0.01 | −0.55 | 0.582 |

| Communication frequency | −0.001 (−0.008, 0.001) | −0.01 | −0.64 | 0.524 |

| Size (subjective) | 0.009 (0.003, 0.019) | 0.08 | 2.05 | 0.041 |

CI, confidence interval.

When the mediation effects of the 2 global social network indicators (brokerage and embeddedness) were individually tested, brokerage mediated the effect of working status (B = 0.010, CI = [0.003–0.020], Z = 2.16), whereas embeddedness pointed to a nonsignificant mediating effect (B = 0.004, CI = [−0.001 to 0.013], Z = 1.18). Conversely, embeddedness (B = 0.022, CI = [0.004–0.043], Z = 2.34) mediated the effect of marital status but not brokerage (B = 0.004, CI = [−0.001 to 0.014], Z = 1.12).

Discussion/Conclusion

The study examined the proximal (subjective number of connections) and distal (brokerage and embeddedness) aspects of the social network and discovered its impacts on the frequency of perceived loneliness. Findings supported the hypothesis that late-life loneliness is composed of proximal and distal characteristics of social connectedness. Moreover, changes in marital and working status may affect late-life loneliness, specifically through the effects of shrinkage and reorganization of the social network. The current study found that brokerage uniquely explained whether or not individuals perceived loneliness. Moreover, losing a spouse or job increases loneliness through a reduction in the self-reported social network size and structural changes in the social network, such as embeddedness and brokerage.

The study suggested that multiple factors, such as demographics, health status, social roles, and social network characteristics, were associated with loneliness. Although the proximal aspects of social networks partially explained loneliness, the distal aspect provided additive information in the final model when all predictors are included. As it presented in subsampled analysis (village L; n = 948), the levels of daily living activity, which may prevent individuals from active social participation, did not change the effects of distal social network characteristics in predicting loneliness.

By applying the cross-validation scheme, the study confirmed that the final model, which included global network measures, predicted loneliness more accurately than other simple models that included demographics and personal social network measures. Notably, basic demographics and health factors were accountable for the majority of individual differences in loneliness, and a limited amount of predictive accuracy was enhanced when social network measures were hierarchically added. This finding indicates that loneliness is typically reported by older adults with shared features, such as low levels of education, poor physical health, and loss of major social roles.

Notably, findings provide a multilevel explanation of the constitution of the subjective experience of loneliness. An individual's social connectedness is characterized by close connections and influenced by emergent properties engendered by social network structures [10]. Despite the similar number and strength of the social network, benefits from the social relationships may vary depending on one's position within the surrounding social network. Consistent with the previous literature, the distal aspect of a social network may be a significant factor in physical and psychological health. For instance, people holding a brokerage position or integrated within a structured social network tend to maintain better health [29, 30]. Benefits from the brokerage position may be associated with abundant social capital gained from increased opportunities for interacting with diverse relationships. In addition, a previous study reported the advantages of deeply embedded positions in social networks in terms of late-life health and highlighted the benefits of being located within a cohesive core group [31]. Individuals integrated into such cohesive groups may share similar values and attitudes and benefit from reliable support [32].

The study conceptualized social networks' characteristics as a predictor of loneliness and an intermediating outcome of changes in social roles. According to the result of mediation analysis, the loss of a spouse leads to loneliness partially through social network changes. The finding indicates that individuals who lost a spouse diminish a single important social relationship and underwent significant changes in the social network structure, especially embeddedness. Accordingly, partner betweenness, that is, one's dependence on the spouse's social relationship, can influence the psychological function of older adults [33], whereas position in the social network can be indirectly dependent on the social network of the spouse. If older adults maintained diverse and embedded social connections via spouses, they might subsequently lose embeddedness after bereavement.

The study observed a similar mediating role for the social network on the relationship between occupational status and loneliness. Older adults who lost their occupation or by job activities may lose social connections apart from the family members [14]. In the current study, occupational status was associated with the subjective size and structural position of the social network, while it was not associated with strength and intimacy of a personal social network. In other words, older adults who did not maintain their working status gained less personal networks and received fewer opportunities for brokerage. This notion may lead to an individual's perceived loneliness. A possibility exists that working activity has entailed one's social interactions with diverse community members, which may comprise a major pathway toward late-life social connectedness.

The convoy model proposes that an individual's social relationships are reorganized in line with changes in social roles over the life span [15]. Although older adults focus on social relationships to preserve emotionally close ties, preserving relationships outside of the family network is beneficial to late-life health outcomes [34]. Accumulating evidence suggests that maintaining diverse nonfamily relationships is crucial for late-life psychological health [35]. Findings indicated that loss of working activity might restrict social interactions with diverse community members, and such loss of social interactions may influence the subjective experience of social connectedness.

These results provide several implications for public health. Although loneliness and related psychosocial constructs have received much attention from public health and epidemiological researchers due to their robust predictability in late-life health outcomes, evidence supporting loneliness as an individualized outcome of external factors remains lacking. If loneliness is merely reflective of an internal psychological factor (trait sensitivity to social disconnection), then assuming the efficacy of community- and population-level intervention will be brutal [36]. In contrast, the study provides evidence that levels of perceived loneliness are partially composed of the external properties of social networks, which can be a target of community-level intervention.

The study has certain limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the study diminished our ability to infer the direction of causality. Although we utilized a cross-sectional mediation model, which heavily relies on the theoretical background, a longitudinal design is required to conclusively support that shrinkage in the global social network is responsible for the link between a social role (working and marital status) and loneliness. A recent study notes that a cross-sectional mediation possibly shows a significant indirect effect when there is no actual longitudinal indirect effect [37] and therefore the result of cross-sectional mediation analysis. Thus, clarifying whether unexamined factors (social relationship sensitivity and general cognitive ability) influenced social network characteristics and loneliness is difficult. For example, loneliness can result from the perceptual capacity in processing necessary social information, and global social network measurements may reflect the attributes of individuals who maintained significant social interactions [38]. Second, although the study noted that loneliness is conceptually distinct from depressive symptoms, the analysis only partially ruled out the possibility that the influence of social disconnection on loneliness may activate loneliness and other depressive symptoms. Loneliness is positively correlated with various symptoms of depression. As such, a further systematic examination is required to clarify whether the observed outcome of increased loneliness is reflective of the dynamic spread of symptom networks [39]. Third, the point that most participants with an occupation were involved in farming (88% of the working participants) may limit the generalizability of the result. Since the KSHAP study only surveyed older adults in a rural Korean township, most participants were involved in farming. Thus, the study findings and contributions should be carefully evaluated. According to other study findings including respondent-centered network data of older Korean adults in an urban area, there was no substantial difference between the KSHAP sample and urban Korean older adults in terms of their social network characteristics [40]. Last, although the study summarized 2 attributes of the global social network, an a priori hypothesis on the mechanism by which each measure explains loneliness is missing. Therefore, future investigation is necessary to develop the association between a specific structural position and psychological functioning.

Even if the current study has several limitations, we utilized individuals' global social network characteristics to go beyond the self-report assessment of social relationship information. We found that the social network's proximal characteristics and distal aspects of the social network affect late-life loneliness. The current research is a pioneer work revealing the relationship between multilayered social network characteristics and loneliness with empirical evidence. Also, this study showed the impact of late-life marital status and occupational status on loneliness and a mediating role of social network characteristics between the social roles and loneliness. It suggests that transition in late-life after retirement makes older adults vulnerable to loneliness by affecting their proximal to distal social relationships.

In conclusion, the current study characterized the multilayered aspect of social disconnection predicting late-life loneliness. Specifically, the distal aspects of social disconnection also affect individuals' perceived loneliness. Moreover, the loss of bridging and cohesive position among community networks may be a critical pathway to psychosocial transition after marital and working status changes.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by and performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University (YUIRB-2011-012-01, 7001988-201612-SB-307-03). All participants provided written informed consent prior to the research procedure.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea, the National Research Foundation of Korea (Grant No. NRF-2017S1A3A2067165).

Author Contributions

J.C., H.K., and S.Y. designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and outlined the manuscript. Y.Y., as the PI of the Korean Social Life, Health and Aging Project, laid and collected the survey dataset that produced the comprehensive data on the social networks of an entire village in South Korea.

References

- 1.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110((15)):5797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong AD, Uchino BN, Wethington E. Loneliness and health in older adults: a mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology. 2016;62((62)):443–9. doi: 10.1159/000441651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30((4)):377–85. doi: 10.1037/a0022826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Terracciano A. Loneliness and risk of dementia. Journals Gerontol Ser B. 2018:1–9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahr HM, Peplau LA, Perlman D. Loneliness a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Contemp Sociol. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkley LC, Browne MW, Cacioppo JT. How can i connect with thee? Let me count the ways. Psychol Sci. 2005 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66((1)):733–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diez Roux AV. Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Feb;1186((1)):125–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39((3)):472–80. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith KP, Christakis NA. Social networks and health. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008 Aug;34((1)):405–29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burt RS, Kilduff M, Tasselli S. Social network analysis: foundations and frontiers on advantage. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64((January 2016)):527–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burt RS. Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornwell B. Network bridging potential in later life: life-course experiences and social network position. J Aging Health. 2009;21((21)):129–54. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrzus C, Hänel M, Wagner J, Neyer FJ. Social network changes and life events across the life span: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2013;139((1)):53–80. doi: 10.1037/a0028601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, Birditt KS. The convoy model: explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. Gerontologist. 2014;54((54)):82–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkley LC, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Masi CM, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63((6)):S375–84. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.s375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Youm Y, Laumann EO, Ferraro KF, Waite LJ, Kim HC, Park YR, et al. Social network properties and self-rated health in later life: comparisons from the Korean social life, health, and aging project and the national social life, health and aging project. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14((14)):102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornwell B, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Graber J. Social networks in the nshap study: rationale, measurement, and preliminary findings. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64((Suppl 1)):i47–55. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burt RS. Network items and the general social survey. Social Networks. 1984;6((4)):293–339. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunbar RIM. The social brain. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23((2)):109–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkinson C, Kleinbaum AM, Wheatley T. Spontaneous neural encoding of social network position. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1((5)):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morone F, Del Ferraro G, Makse HA. The k-core as a predictor of structural collapse in mutualistic ecosystems. Nat Phys. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cacioppo JT, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Alone in the crowd: the structure and spread of loneliness in a large social network. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97((97)):977–91. doi: 10.1037/a0016076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho MJ, Kim KH. The diagnostic validity of the CES-D (Korean version) in the assessment of DSM-III-R major depression. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1993;32((3)):381–99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, Burleson M, Berntson GG, Nouriani B, et al. Loneliness within a nomological net: an evolutionary perspective. J Res Pers. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schafer MH. Structural advantages of good health in old age: investigating the health-begets-position hypothesis with a full social network. Res Aging. 2013;35((3)):348–370. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang S, Choi SH, Lee B, Kwon J, Na D, Han SH. The reliability and validity of the Korean instrumental activities of daily living (K-IADL) J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schafer MH. Structural advantages of good health in old age: investigating the health-begets-position hypothesis with a full social network. Res Aging. 2013;35((3)):348–370. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornwell B. Good health and the bridging of structural holes. Soc Networks. 2009;31((1)):92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burt RS. Neighbor networks. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkinson C, Kleinbaum AM, Wheatley T. Spontaneous neural encoding of social network position. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1((5)):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cornwell B, Laumann EO. Network position and sexual dysfunction: implications of partner betweenness for men. Am J Sociol. 2011;117((1)):172–208. doi: 10.1086/661079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharifian N, Manly JJ, Brickman AM, Zahodne LB. Social network characteristics and cognitive functioning in ethnically diverse older adults: the role of network size and composition. Neuropsychology. 2019 doi: 10.1037/neu0000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiori KL, Antonucci TC, Cortina KS. Social network typologies and mental health among older adults. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61((1)):P25–32. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holt-lunstad J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. 2018 doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maxwell SE, Cole DA, Mitchell MA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011 doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.606716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanai R, Bahrami B, Duchaine B, Janik A, Banissy MJ, Rees G. Brain structure links loneliness to social perception. Curr Biol. 2012;22((22)):1975–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried EI, Bockting C, Arjadi R, Borsboom D, Amshoff M, Cramer AOJ, et al. From loss to loneliness: the relationship between bereavement and depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015 May;124((2)):256–65. doi: 10.1037/abn0000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee EY, Kim HC, Rhee Y, Youm Y, Kim KM, Lee JM, et al. The Korean urban rural elderly cohort study: Study design and protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]