Abstract

Objective

Within the fields of anthropology and osteoarcheology, human teeth have long been studied to understand the diet, habits, and diseases of past civilizations. However, no complete review has been published to collect and analyze the extensive available data on caries prevalence in European man (Homo sapiens) over time.

Method

In this current study, the two databases, Scopus and Art, Design, and Architecture Collection, were searched using predefined search terms. The literature was systematically reviewed and assessed by two of the authors.

Results

The findings include a significant nonlinear correlation with increasing caries prevalence in European populations from 9000 BC to 1850 AD, for both the number of carious teeth and the number of affected individuals.

Conclusion

Despite the well-established collective belief that caries rates fluctuate between different locations and time and the general view that caries rates have increased from prehistoric times and onwards, this is to our knowledge the first time this relationship has been proven based on published data.

Keywords: Anthropology, Bioarcheology, Epidemiology, Europe, Systematic review

Introduction

The caries disease has affected Homo sapiens for as long as it has existed, resulting in the development of carious lesions in the teeth. Evidence of the disease has been found not only in Homo sapiens, as reviewed in the current study, but also in Neanderthals [Topić et al., 2012] and humanoids [Fuss et al., 2018], evidently accompanying humanity throughout evolution. In the field of archeology, and in particular bioarcheology, the study of human dentition and its pathologies has long been a subject of major interest and has therefore been extensively studied. Due to their low percentage of organic matter, human jaws and teeth remain well preserved post mortem, enabling these structures to provide important information on human subsistence and mortality throughout history. The highly mineralized tooth and bony tissues can be studied, sometimes epochs after burial, in order to assess age, reconstruct dietary patterns, obtain an understanding of complex social and cultural shifts, and provide an insight into past civilizations [Forshaw, 2004]. More recently, ancient DNA extracted from the well-protected dental pulp tissues has been studied in order to understand migration patterns of populations, cultures, and goods. It is irrefutable that dental tissues possess great research potential and provide valuable accounts of prehistoric life even for times prior to the development of written language.

Dental caries involves complex pathological processes in the dental biofilm (often referred to as dental plaque), including a shift in ecology favoring the microbiological fermentation of dietary carbohydrates into acids [van Houte, 1994]. Acid production may lead to the net demineralization of dental hard tissues, resulting in the formation of carious lesions, which may develop into cavities in the teeth. The disease is as old as man, but its prevalence has varied over time and in different locations. Oral microbiota are not merely able to ferment sucrose, but other carbohydrates, such as fructose and starch, can also be utilized [Kashket et al., 1994; Lingström et al., 2000]. Since the process of dental caries is complex and, in addition to the local oral microbiota, includes intricate interactions between salivary, dietary, genetic, anatomic, and physiologic factors [Chapple et al., 2017], no simple explanatory model is readily available when contemplating caries frequencies in historic man.

Changes in caries frequency recorded in archeological human remains are commonly explained by variations in dietary factors [Larsen, 2002]. During the Neolithic revolution starting around 10,000–8000 BC, with transitions in many human cultures from hunting and gathering to agriculture, the literature has reported a change in caries occurrence with increasing rates [Wittwer-Backofen and Tomo, 2008]. This has been suggested by both studies of human remains [Wittwer-Backofen and Tomo, 2008] and studies of the ancient oral microbiota [Adler et al., 2003]. The increase in caries prevalence is commonly explained by the dietary changes, including preparation techniques and food-crop cultivation this transition involved [Larsen, 2002].

Another well-known shift in the caries burden in human beings occurred with the advancement of industrialization during the 19th century, introducing sugars and processed foodstuffs to the masses, leading to an increase in disease prevalence. Later, the implementation and general adaptation of preventive strategies, such as fluoride dentifrices, as well as the development of and advances in dentistry, have led to improved dental health. No comprehensive systematic review of the literature on the caries prevalence in historic and prehistoric European man has been published, but one meta-analysis of caries prevalence and tooth loss before and after the 19th century in Europe has previously been published [Müller and Hussein, 2017], reporting a small to moderate shift in dental disease. In textbooks, more general and global anthropological overviews of the historical occurrence of dental caries have been published [Lanfranco and Eggers, 2012]. The aim of the current study was to review the literature and present a collected data series on caries prevalence in Homo sapiens populations in the past, as well as commenting on findings from a joint historical, osteological, archeological, and odontological perspective.

Methods

This review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Moher et al., 2009]. The search strategy was reviewed for accuracy using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies criteria [McGowan et al., 2016].

The search strategy was developed by the librarian authors (E.H., H.S.) in collaboration with the other authors. The search was deliberately broad in an effort to include all the relevant articles. One multi-disciplinary database − Scopus − and one archeology specific − Art, Design, and Architecture Collection − were used. The searches were conducted on 27 May 2020 using the following search concepts and their synonyms: caries, archeological remains, Europe. An additional search was performed on 20 June 2021, using the same search strategy. For the full search strategy, see Table 1. No restrictions were applied to years searched or language of publications. The searches resulted in 1,580 results and, after de-duplication, 1,493 references remained. The references were downloaded into the Rayyan web application for systematic reviews to facilitate the review process [Ouzzani et al., 2016].

Table 1.

Search terms

| a. Scopus search | |

|

| |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

|

| |

| #3 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (Andorra* OR Austria OR Austrian OR Balkan OR Belgium OR Belgian OR Albania* OR “Baltic States” OR Estonia* OR Latvia* OR Lithuania* OR Yugoslavia* OR Bosnia* OR Herzegovina* OR Bulgaria* OR Croatia* OR Czech OR Hungary OR Hungarian OR Kosovo OR Kosovar OR Macedonia* OR Moldova* OR Montenegro OR Montenegrin OR Poland OR Polish OR Romania* OR Serbia* OR Slovakia* OR Slovenia* OR France OR French OR Germany OR German OR Greece OR Greek OR Ireland OR irish OR Italy OR Italian OR Liechtenstein* OR Luxembourg* OR Cyprus OR Cypriot OR Malta OR Maltese OR Monaco OR Monegasque OR Netherlands OR Dutch OR Portugal OR Portuguese OR “San Marino” OR Sammarinese OR Scandinavia* OR Denmark OR Danish OR Greenland* OR Finland OR Finnish OR Iceland* OR Norway OR Norwegian OR Svalbard OR Sweden OR Swedish OR Spain OR Spanish OR Switzerland OR Swiss OR “United Kingdom” OR British OR English OR “Channel Islands” OR England OR Ireland OR Irish OR Scotland OR Scottish OR Wales OR Welsh OR Gaelic OR Russia* OR Belarus* OR Ukraine OR Ukranian OR Europe*) |

|

| |

| #2 | TITLE-ABS-KEY (centuries OR century OR medieval OR medieaval OR Viking OR vikings OR hunter-gatherer* OR “grave yard*” OR graveyard OR churchyard* OR “church yard” OR burial OR burials OR exhumed OR exhumination OR excavated OR bio-archaeolog* OR bioarchaeolog* OR Historic* OR history OR Paleolithic OR ancient OR paleontol* OR paleodontol* OR archaeol* OR grave OR graves OR cemetery OR cemeteries OR massgrave*) |

|

| |

| #1 | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“oral health” OR “dental disease*” OR “dental pathology” OR “oral pathology” OR “Dental Caries” OR caries OR carious) |

|

| |

| b. Art, design and architecture collection (proquest) search | |

|

| |

| #5 | Limit Peer reviewed |

|

| |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

|

| |

| #3 | Andorra* OR Austria OR Austrian OR Balkan OR Belgium OR Belgian OR Albania* OR “Baltic States” OR Estonia* OR Latvia* OR Lithuania* OR Yugoslavia* OR Bosnia* OR Herzegovina* OR Bulgaria* OR Croatia* OR Czech OR Hungary OR Hungarian OR Kosovo OR Kosovar OR Macedonia* OR Moldova* OR Montenegro OR Montenegrin OR Poland OR Polish OR Romania* OR Serbia* OR Slovakia* OR Slovenia* OR France OR French OR Germany OR German OR Greece OR Greek OR Ireland OR Irish OR Italy OR Italian OR Liechtenstein* OR Luxembourg* OR Cyprus OR Cypriot OR Malta OR Maltese OR Monaco OR Monegasque OR Netherlands OR Dutch OR Portugal OR Portuguese OR “San Marino” OR Sammarinese OR Scandinavia* OR Denmark OR Danish OR Greenland* OR Finland OR Finnish OR Iceland* OR Norway OR Norwegian OR Svalbard OR Sweden OR Swedish OR Spain OR Spanish OR Switzerland OR Swiss OR “United Kingdom” OR British OR English OR “Channel Islands” OR England OR Ireland OR Irish OR Scotland OR Scottish OR Wales OR Welsh OR Gaelic OR Russia* OR Belarus* OR Ukraine OR Ukranian OR Europe* |

|

| |

| #2 | Centuries OR century OR medieval OR medieaval OR Viking OR vikings OR hunter-gatherer* OR “grave yard” OR «grave yards» OR graveyard OR churchyard* OR “church yard” OR burial OR burials OR exhumed OR exhumination OR excavated OR bio-archaeolog* OR bioarchaeolog* OR Historic* OR h istory OR Paleolithic OR ancient OR paleontol* OR paleodontol* OR archaeol* OR grave OR graves OR cemetery OR cemeteries OR massgrave* |

|

| |

| #1 | “oral health” OR “dental disease” OR “dental diseases” OR “dental pathology” OR “oral pathology” OR “Dental Caries” OR caries OR carious |

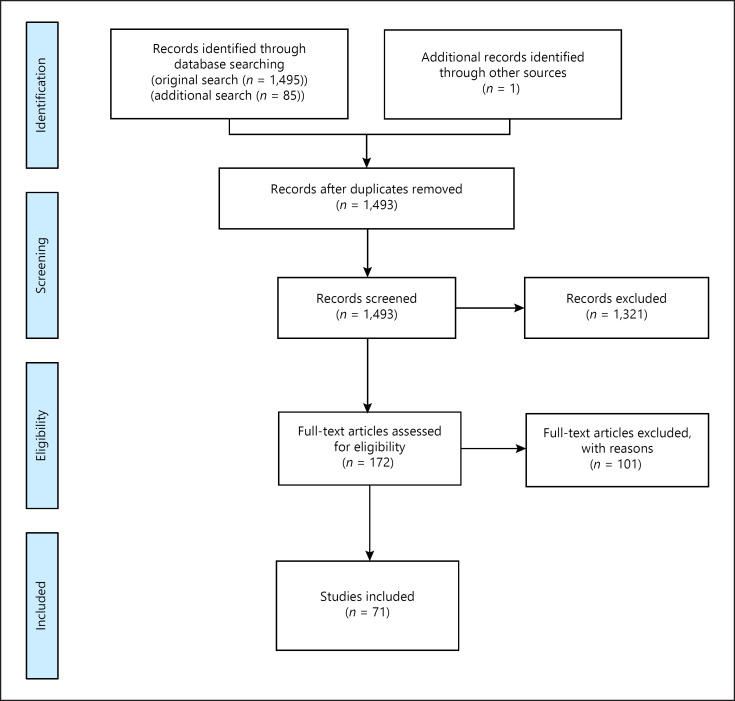

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection and inclusion process. The inclusion criteria were i) English as the publication language, ii) time of death of studied remains no later than 1850, iii) geographic area Europe (current region), iv) cohorts comprising at least 10 individuals, v) permanent dentition, vi) data presented for either carious teeth or individuals with carious lesions, and vii) manifest lesions. Articles not presenting types of teeth recorded, methodology for caries diagnostics, or the stage of recorded carious lesions were excluded from the study, as well as articles that did not present any numerical data. Since only the permanent dentition was studied, only articles presenting data for individuals over the age of 12 were included and mixed dentitions were excluded.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Authors C.B. and E.B. screened all the titles and abstracts independently, resulting in 161 articles from the original search and 10 articles from the updated search, which were included for eligibility assessment in full text. An additional manual search based on the citations and references for included articles resulted in the identification of one additional relevant article. Before starting the screening, the authors calibrated their assessment by assessing 10 abstracts together. When either of the authors was unsure, the other one was consulted. In cases of disparity, a third party (P.L.) was consulted. For the full-text reading, both C.B. and E.B. read the manuscripts and decided on inclusion or exclusion and, in the event of uncertainty, P.L. was consulted. Data extraction (including country, time period, examination type, age at death, teeth studied, gender, number of individuals and teeth, and individuals and/or teeth with caries) and further data work including statistics were performed by C.B. and E.B. supported by P.L.

Risk of bias was generally regarded as low, since special attention was paid to the inclusion criteria and inclusion process. A formal assessment of risk of bias was not performed, due to the nature of the bioarcheological examinations. However, in Table 2, the included articles are presented with the extracted information, which gives a further insight into each included study and its limitations.

Table 2.

Included studies and their characteristics

| First author/year | Country | Time period | Examination type | Age at death, yr or teeth studied | Gender | Total number of individuals | Total number of teeth | Individuals with caries, % | Teeth with caries, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Characteristics of included studies dated before 2000 BC | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Beck et al. [2018] | Spain | 2800–2100 cal BC | Clinical | 13–61+ | Mixed | 17 | 485 | − | 9.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Spain | 2800–2100 cal BC | Clinical | 31–61+ | Mixed | 51 | 3,085 | − | 7.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Frayer [2004] | Czech Republic/Slovakia | 5300–5260 BC | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 108 | 2,597 | 50.0 | 6.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Formicola [1987] | Italy | 4th millennium BC | Clinical | 18+ | Males | 10 | 225 | 60 | - | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Garłowska [2001] | Poland | 4300–4000 BC | Clinical | 20+ | Mixed | 54 | 1,187 | 42.5 | 4.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Karsten et al. [2015] | Ukraine | 3951–2620 cal BC | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Mixed | 35 | 231 | 31.4 | 9.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lillie [2008] | Czeh Republic | 10000–4500 BC | Clinical | 18–50+ | Mixed | 59 | 1,219 | 46.9 | 3.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lunt [1974] | Scotland | 3000–1800 BC | Clinical | 6+, permanent teeth | Unknown | 100 | 656 | − | 1.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Masotti et al. [2019] | Italy | Approx. 3000 BC | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Mixed | At least 18 | 354 | − | 16.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Radović and Stefanović [2013] | Serbia | Neolithic | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Mixed | 32 | 500 | − | 1.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Silvana et al. [1985] | Italy, Sicily | 9030–9300 BC | Clinical | Young mature adults | Mixed | 10 | 167 | − | 13.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| b. Characteristics of included studies dated year 2000 BC-0 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Gualandi [1992] | Italy | 500–300 BC | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 71 | 1,201 | − | 11.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Keenleyside [2008] | Greece/Bulgaria | 5th–2nd centuries BC | Clinical | 18–50+ | Mixed | 162 | 2,939 | 53.8 | 7.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lunt [1974] | Scotland | 300 BC to 0 | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Unknown | 20 | 301 | − | 6.6 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Michael and Manolis [2014] | Greece | 7th century BC to 2nd century AD | Clinical | 20–51+ | Mixed | 32 | 381 | 46.9 | 7.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Michael et al. [2017] | Greece | 900 BC to 400 AD | Clinical | 20–51+ | Mixed | 46 | 727 | − | 6.1 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Masotti et al. [2013] | Italy | 600–300 BC | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Mixed | 80 | 680 | 26.2 | 5.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Šikanjić [2006] | Croatia | 9th–10th century | Clinical | 18–45+ | Mixed | 30 | 292 | − | 4.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| c. Characteristics of included studies dated year 1–999 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Arnold et al. [2007] | Ukraine | 8th–10th century | Clinical | 18–40 | Unknown | 14 | Unknown | − | 1.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Ukraine | 8th–10th century | Clinical | 18–40 | Unknown | 11 | Unknown | − | 4.2 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Bennike [1994] | Denmark | 800–1000 | Clinical | 20–55+ | Mixed | 31 | 456 | 29 | 4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Denmark | 800–1000 | Clinical | 20–55+ | Mixed | 39 | 621 | − | 4.2 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Bertilsson et al. [2020] | Sweden | 10th century | Clinical | 20–55 | Mixed | 18 | 370 | 77.8 | 11.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Bonsall [2014] | England | 270–410 | Clinical | 18–50+ | Mixed | Unknown | 3,227 | 59.0 | 9.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Chazel et al. [2005] | France | 4th–10th century | Clinical | 12–36+ | Unknown | 36 | 355 | − | 9.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Cucina et al. [2006] | Italy | 2nd–3rd century | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 77 | 1,408 | − | 2.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Djurić Srejić [2001] | Serbia | 10th century | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 105 | 1,680 | 55.7 | 8.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Fernandez-Martinez et al. [2020] | Spain | 300–600 | Clinical | 18–41 | Mixed | 21 | Unknown | 42.9 | 18.8 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Jílková et al. [2019] | Czeh Republic | 9th–10th century | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 91 | Unknown | 78.0 | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Liebe-Harkort [2012] | Sweden | 0–260 | Clinical | 21–60+ | Mixed | 96 | 1,794 | 92.6 | 44.2 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lunt [1974] | Scotland | 400–1000 | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Unknown | 64 | 1,041 | − | 4.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Scotland | 800–1000 | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Unknown | 22 | 307 | − | 2.9 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Scotland | 1200–1500 | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Unknown | 29 | 400 | − | 6.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Manzi et al. [1999] | Italy | 1st–3rd century | Clinical | 20–50+ | Mixed | 64 | 872 | 35.9 | 4.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Italy | 1st–3rd century | Clinical | 20–50+ | Mixed | 50 | 942 | 52.0 | 6.1 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Italy | 7th century | Clinical | 20–50+ | Mixed | 48 | 912 | 70.8 | 12.6 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Marin et al. [2005] | Croatia | 10th–11th century | Clinical | 13–46+ | Unknown | 74 | 923 | 50.0 | 9.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Meinl et al. [2010] | Austria | 700–800 | Clinical | 20–61+ | Mixed | 136 | 2,215 | 54.7 | 14.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Miclon et al. [2019] | France | 7th–18th century | Clinical | 15+ | Mixed | 37 | Unknown | − | 9.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Novak [2015] | Ireland | 5th–11th century | Clinical | 18–50+ | Mixed | 167 | 3,233 | − | 3.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Peko and Vodanović [2016] | Croatia | 3rd–5th century | Clinical | 15–45+ | Mixed | 100 | 2,041 | 53.5 | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Šlaus et al. [2011] | Croatia | 3rd–6th century | Clinical | 18–35+ | Mixed | 103 | 1,992 | − | 9.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Croatia | 7th–11th century | Clinical | 18–35+ | Mixed | 151 | 1,590 | − | 11.7 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Swales [2019] | England | 8th–12th century | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 248 | 5,618 | 39.0 | 4.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Thornton [1991] | England | 4th century | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 91 | Unknown | 70.0 | 14.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Walter et al. [2016] | England | 120–1539 AD | Clinical | 13–36+ | Mixed | 371 | Unknown | 63.0 | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Yanko et al. [2021] | Ukraine | 400 | Clinical + radiographic | 18+ | Mixed | 25 | 647 | 28.0 | 1.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| d. Characteristics of included studies dated year 1000–1499 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Adamic and Šlaus [2017] | Croatia | 13th–16th century | Clinical | 18+ | Mixed | 30 | 768 | − | 6.2 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Esclassan et al. [2009] | France | 12th–14th century | Clinical | 20–30+ | Mixed | 58 | 1,395 | − | 18.6 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Chazel et al. [2005] | France | 11th–15th century | Clinical | 12–36+ | Unknown | 107 | 1,183 | − | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Gawlikowska-Sroka et al. [2013] | Poland | 12th–15th century | Clinical | 22–55 | Mixed | 58 | Unknown | 54.0 | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kerr et al. [1988] | Scotland | 1300–1600 | Clinical | 6–45+ permanent teeth | Unknown | 68 | 1,088 | 29.4 | 5.1 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kerr et al. [1990] | Scotland | 13th–17th century | Clinical | 6–45+ permanent teeth | Unknown | 101 | 1,869 | 43.6 | 7.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lopez et al. [2012] | Spain | 11th–15th century | Clinical | Adults and mature | Mixed | At least 19 | 1,012 | − | 4.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| López-Morago et al. [2020] | Spain | 1000–1400 | Clinical | 16–60 | Mixed | 60 | 961 | 50 | 5.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lucas et al. [2010] | France | 11th–12th century | Clinical + radiographic | 20+ | Mixed | 60 | 788 | 80.0 | 17.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lunt [1974] | Scotland | 1200–1500 | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Unknown | 29 | 400 | − | 6.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| McKenzie et al. [2020] | Ireland | 1200–1600 | Clinical | Adults 18+ | Mixed | 356 | 6,238 | 37.6 | 5.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Michael et al. [2017] | Greece | 13th–14th century | Clinical | 20–51+ | Mixed | 16 | 126 | − | 16.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Olsson and Sagne [1976] | Sweden | 1060–1160 | Clinical | 14–60+ | Mixed | 51 | Unknown | 43.8 | 4.2 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Sweden | 1160–1200 | Clinical | 20–60+ | Mainly men | 10 | Unknown | 60.0 | 5.5 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Sweden | 1200–1536 | Clinical | 14–60+ | Mixed | 36 | Unknown | 55.8 | 8.1 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Šlaus et al. [1997] | Croatia | 14th to 17th century | Clinical | 15+ | Mixed | 68 | 420 | − | 9.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Šlaus [2000] | Croatia | 14th–18th century | Clinical | 16–60+ | Mixed | 68 | 765 | − | 10.9 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Šlaus et al. [2018] | Croatia | 1100–1400 | Clinical | 18–36+ | Mixed | 112 | 2,131 | − | 17.1 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Trombley [2019] | Italy | 1300–1500 | Clinical | 18–50+ | Mixed | 75 | 1,534 | − | 20.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Ubelaker and Pap [2008] | Hungary | 11th century | Clinical | Permanent teeth | Mixed | Unknown | 2,067 | − | 3.8 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Watt et al. [1997] | Scotland | 1240–1440 | Clinical | Juvenile-elderly adults | Unknown | 734 | 3,706 | − | 6.7 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| e. Characteristics of included studies dated year 1500–1699 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Adamic and Šlaus 2017 | Croatia | 15th–18th century | Clinical | 18+ | Mixed | 30 | 678 | − | 6.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Arcini et al. [2020] | Sweden | 17th–19th century | Clinical | 20–59 | Mainly men | 220 | Unknown | 37.0 | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Bertilsson et al. [2021] | Sweden | 1500–1620 | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 205 | 4,951 | 68.0 | 13.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Bonsall and Pickard [2015] | England | 1500 | Clinical | 18–50+ | Mixed | 200 | 2,037 | 55.5 | 8.1 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Chazel et al. [2005] | France | 16th–17th century | Clinical + radiographic | 12–36+ | Unknown | 109 | 1,267 | − | 18.8 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Giuffra et al. [2020] | Italy | 1583 | Clinical | Adults 18+/permanent teeth | Mixed | 81 | 868 | 50.7 | 5.2 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lopez et al. [2012] | Spain | 16th–18th century | Clinical | Adults and mature | Mixed | At least 77 | 1210 | − | 12.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lingström and Borrman [1999] | Sweden | 1621–1640 | Clinical + radiographic | 16–45+ | Unknown | 65 | 943 | 60.3 | 11.6 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Miliauskiene and Jankauskas [2015] | Lithuania | 16th–17th century | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 150 | 3,015 | 80.0 | 20.8 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lithuania | 16th–17th century | Clinical | Adults | Mixed | 39 | 981 | 64.0 | 11.4 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Petersone-Gordina et al. [2018] | Latvia | 15th–17th century | Clinical | 18–31+ | Mixed | 225 | 4,591 | 55.2 | 6.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Šlaus et al. [2018] | Croatia | 1400–1700 | Clinical | 18–36+ | Mixed | 161 | 2,655 | − | 14.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Smith [2019] | England | 1570–1740 | Clinical | 18+ | Mixed | 224 | 5,191 | 87.0 | 14.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Varrela [1991] | Finland | Late medieval to 1600 | Clinical | 17–45+ | Mixed | 288 | 3,697 | 54.1 | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Vilkama et al. [2016] | Finland | 17th–18th century | Clinical | 20+ | Mixed | 176 | 1,388 | 43.0 | 23.2 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Wells [1968] | England | 17th–19th century | Clinical | 13+ | Unknown | 192 | 622 | 0 | 17.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| f. Characteristics of included studies dated year 1700–1850 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Geber and Murphy [2018] | Ireland | 1847–1851 | Clinical | 18–46+ | Mixed | 363 | 6,860 | 79.9 | 19.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Malčić et al. [2011] | Croatia | 18th century | Clinical | 15–45+ | Mixed | 104 | 1,610 | 74.4 | 18.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Quade and Binder [2018] | Austria | 1809 | Clinical | 14–45 | Mixed | 30 | 591 | 83.8 | − | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Seiler et al. [2017] | Italy, Sicily | 18th–19th century | Clinical | Juvenile–elder | Mixed | 111 | Unknown | − | 58.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Ubelaker et al. [2009] | Spain | 19th century | Clinical | 18–90 | Mixed | 133 | 346 | − | 27.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Whittaker and Molleson [1996] | England | 18th century | Clinical + radiographic | 17–55+ | Mixed | 66 | 1,576 | 94.0 | 13.1 | |

Statistical work was performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science) software. Reported means were extracted from the articles. Analyses of correlations between caries prevalence and time, for both teeth and individuals, were performed using Spearman's rank correlation test (2-tailed) for each cohort and significance was set at 0.05*.

Results

The data search and exclusion process resulted in 71 articles published between 1968 and 2021, presenting a total of 90 cohorts. Table 2 summarizes the characterizations of included studies.

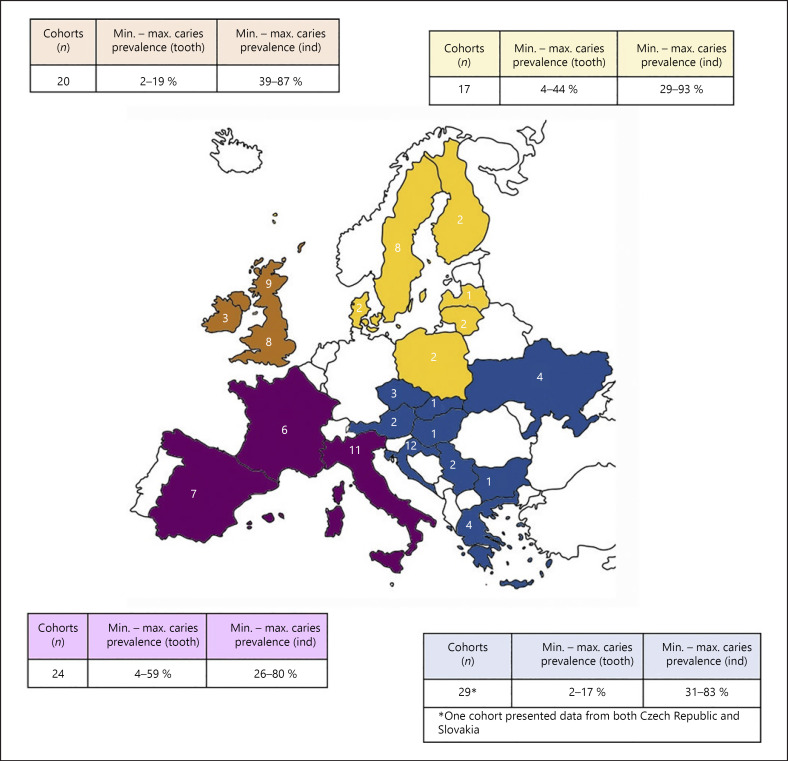

In order to visualize the results, cohorts were, as specified in present-day geography, arranged into four regions; the Baltic Sea countries including Denmark, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Sweden (n = 16), North-western Europe including Ireland and the United Kingdom, comprising England, Scotland, and Wales (n = 20), South-western Europe including France, Spain, and Italy (n = 25), and South-eastern and Central Europe including Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Serbia, Slovakia, and Ukraine (n = 29) (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, several countries were not represented in the data. The minimum and maximum caries prevalence for teeth varied between 2 and 59% and, for individuals, between 26 and 93% in the four geographic areas. The Baltic Sea and south-west regions had a numerically higher maximum value for carious teeth compared with the other two regions. No caries-free populations were found.

Fig. 2.

Caries prevalence in different geographical areas and number of cohorts per country and region.

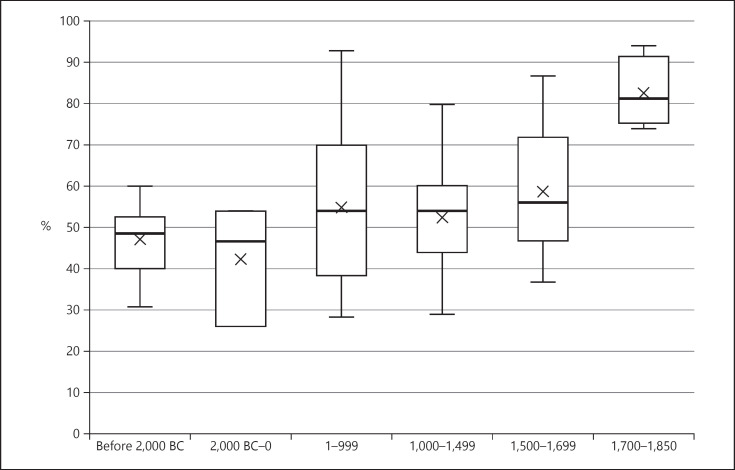

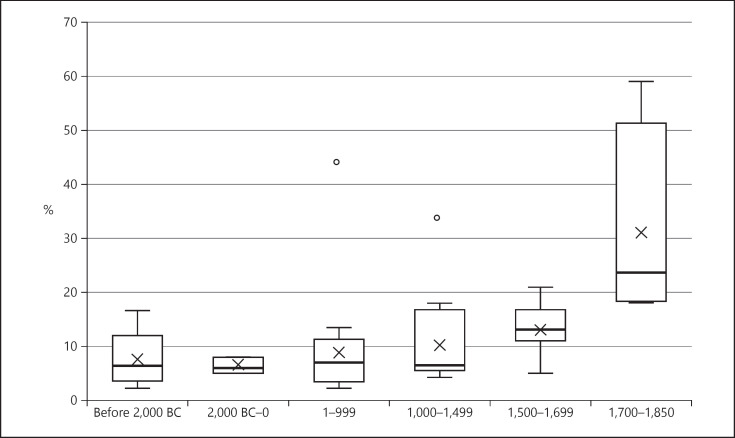

The time periods of populations in the included studies ranged from 9000 BC to 1850 AD. In data presentation, the cohorts were grouped as follows: before 2000 BC (n = 11), 2000 BC to year 0 (n = 7), 1–999 (n = 29), 1000–1499 (n = 21), 1500–1699 (n = 16) and 1700–1850 (n = 6). A large variation in caries prevalence was found within each time period (Fig. 3,4). A steady increase in the number of both affected individuals and carious teeth was seen from prehistoric times to 1850.

Fig. 3.

Manifest carious lesions in groups ordered by chronological time of death. The line indicates the median, the box the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles. The mean is shown as x and the line indicates the median.

Fig. 4.

Number of teeth with manifest carious lesions in groups ordered by chronological time of death. The line indicates the median, the box the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers the 10th and 90th percentiles. The mean is shown as x and the line indicates the median. Dots indicate outliers.

Cohorts ranged from 10 to 734 individuals and the number of examined teeth ranged from 126 to 6,860. Information on the number of individuals in the studied cohort and the number of teeth examined was presented for the majority of the cohorts (n = 89, n = 80) and no cohort lacked information on both variables. The individuals' biological age at the time of death ranged from 13 to more than 60 years of age, although some articles merely stated that “adults” were studied, without any further specification regarding age, and others stated that permanent teeth had been studied, with no further declaration of age at the time of death. In 68 of the cohorts, the biological sex of the subjects was specified in the article. The majority of publications studied cohorts of mixed gender populations, but two publications included only male subjects [Lucas et al., 2010; Quade and Binder, 2018].

Already during Neolithic times, around 10% of teeth and almost half the individuals in included populations were affected by caries. The prevalence for both individuals and teeth was lower during the prehistoric and historic time periods than in the early modern period cohorts. A dramatic increase in caries prevalence could be seen during the early modern period, where up to 95% of individuals and 60% of teeth were affected. A significant positive nonlinear correlation was found between time and caries prevalence, for both individuals and teeth with caries (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistical work

| Cohorts, n | Correlation coefficient | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of teeth with manifest caries over time | 80 | 0.425 | <0.001 |

| Prevalence of individuals with manifest caries over time | 50 | 0.336 | 0.017 |

The correlation between time and caries prevalence for teeth and individuals, using Spearman's rank correlation test (two-tailed).

Discussion

The findings in the current study indicate a general nonlinear increase in caries prevalence in Europe over time, from 9000 BC to 1850 AD, which correlates well with previous knowledge of the disease and its main risk factors [Selwitz et al., 2007]. This trend is explained by a successive increase in the access to and consumption of carbohydrates, which is related to the domestication of crops, the development of agriculture and the use of different food preparation processes. Around 10% of the teeth and almost half the individuals in the included cohorts already suffered from dental caries during Neolithic times. This relatively high occurrence of dental caries is explained by dietary changes following the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture. The caries prevalence increased during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Early Middle Ages, explained by the continuous domination and development of agriculture. During the late Middle Ages and early modern period, a dramatic increase in caries prevalence was seen, explained by the introduction of sucrose and other, for the oral microbiota, fermentable carbohydrates in the diet. This change, with increasing rates of dental caries over time, confirms the previously assumed relationship between disease burden and chronological time.

The findings also included variations in caries prevalence within time periods and regions, which must be attributed and related to the circumstances of each cohort regarding nutrition, technology, societal context, socioeconomics, genetics, geology, and geography. Unknown factors may also play a role in the caries development within these cohorts. Throughout history, Europe has shown large-scale heterogeneity regarding resources, culture, and populations, which probably influences the data, as well as time variations in societal and industrial development for the different cohorts. However, all these factors appear to be overridden by the time aspect reflected in the results of the current study. In the light of contemporary epidemiological data, it is interesting to consider that, in spite of an overall reduction in caries prevalence, large variations remain in modern man, both within and between countries [Kassebaum et al., 2015; Norderyd et al., 2015].

Variations in the collected data highlight the difficulty involved in predicting caries prevalence based merely on the geographic location or chronologic time, without considering the contextual differences in the studied population. However, in spite of the influence of multiple complex factors, a clear positive trend for dental caries can be seen in Europe from prehistoric times to the end of the industrial revolution.

Since research data within the field of archeology have traditionally been presented in a wide range of ways and a proportion of the studies are written in non-English languages, articles are commonly found in local journals rather than global databases. It is therefore probable that a number of cohorts were not identified in the literature search since they were not eligible for the search terms used in the current study. Importantly, many articles on the topic were published at a time when scientific standards for data collection and presentation were different and not comparable to current standards. Consequently, a number of articles detected in the original search were unfortunately excluded due to these shortcomings.

Possible uncertainties in analyzed data must be considered, such as examinations only being performed by a single individual and a fairly large proportion of examiners in the included studies not being dentists or specialists in odontology. The lack of radiographic imaging in the majority of the included articles is a probable source of bias, as it is well known that radiographic imaging can provide additional information on caries diagnostics, especially proximal lesions [Lucas et al., 2010]. In ancient human remains, teeth can rarely be associated with specific individuals due to fragmentation or damage, burial practices, and ground conditions, which creates uncertainty in the data. Several of the included studies presented data for only either teeth or individuals with caries but not both. It is also important to note that the wide range in the number of subjects and teeth reviewed in included articles, extending from 10 to over 700 individuals and 126 to more than 6,000 teeth, poses a limitation in the current study. Unfortunately, some geographic regions were not represented in the collected data and, in the current study, they must be regarded as terra incognita regarding the historical burden of dental caries. To provide a more comprehensive depiction, additional research is needed in several regions and time periods. Due to the nature of archeological methodology, bias assessment was not regarded as realistic in the present study.

Lost teeth were not considered in the current analysis, which can be regarded as a source of bias, since the lost teeth contain valuable information that cannot be considered [Hillson, 2001]. The etiology of tooth loss in archeological remains varies and is represented by both ante-mortem tooth loss, due to causes including dental caries, periodontology, trauma, extractions, and infections, and additionally tooth loss occurring post mortem. Because of the unclear etiology and the aim of this study only to study dental caries, this factor was not included in the current work but must be regarded as a potential source of error.

An additional risk of bias is the variation in biological age at death. In the current review, this factor has not been included simply because age determination is not precise enough in the majority of the included cohorts (see Table 2). Archeological age assessment is frequently based on osteological analysis, which is more difficult for adults compared with younger individuals [Mays, 2015]. The risk of caries correlates with age, due to increased exposure to the oral environment and associated risk factors. Carious lesions should thus accumulate during the life span in populations without access to dental treatment [Hillson, 2001]. Since the life expectancy of Homo sapiens has fluctuated from prehistoric to modern times [Angel, 1969], but with a general increase in life expectancy during the modern period, it is tempting to draw the conclusion that the probability of finding carious lesions increases with time as well. However, the risk of tooth loss, both ante- and post mortem, also increases with increasing biological age at death [Durić et al., 2004]. It is also well known that life expectancy is related to a number of factors such as biological sex, socioeconomics, genetics, environment, and geography and is not linear through history. The relationship is therefore complex. Because of this, the current study has not included lost teeth and biological age at death in the analysis of the data, but future research should aim to include both factors, even though this would substantially limit the number of included cohorts.

In the future, the authors would like to highlight the importance of quality assurance in dental examinations of archeological remains, together with the need for an increase in the international accessibility of published data, as the large number of articles that had to be excluded from this study due to limitations in publication language, methodology, and/or data presentation is truly a lost opportunity. To improve the quality of published data, the authors suggest using systematic examination protocols, including (1) recordings of the age, number, distribution, biological sex, and age at death of the studied remains, as well as the number of studied teeth and lost teeth, (2) defining the stage of carious lesions examined, included and recorded, (3) using a caries index for recording and comparing the occurrence of dental caries, (4) utilizing radiographic imaging for diagnostics or at least for the reliability control of the clinical diagnostics, and (5) examiner standardization and calibration to improve intra- and inter-examiner reliability. These aspects have previously been highlighted in a study by Liebe-Harkort et al. [2010]. It must be remembered that the opportunity to study these fascinating historical populations, and thereby obtain an insight into sustenance and life and death in ancient times, becomes rarer as time passes.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first time an attempt has been made to summarize the occurrence of dental caries in Europe based on data from Neolithic times to 1850 AD. In spite of its limitations, the current study conclusively identifies a general trend towards increasing caries prevalence for both individuals and teeth in past European populations, from 9000 BC to 1850 AD. Increasing caries rates are mainly explained by dietary changes related to agriculture and industrialization, even though various other risk factors influencing and adversely affecting the oral microbiota and dental hard tissues must be considered when contemplating the historical caries burden of specific cohorts.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no competing interests to report.

Funding Sources

No funding.

Author Contributions

C.B. wrote the original draft, performed article analysis together with E.B., curated data, and conducted the formal statistical analysis. She was also responsible for visualization, together with E.B. and P.L. E.B. contributed to the analysis, writing, and curating of the data. S.S. contributed archeological expertise and participated in editing the manuscript. E.H. and H.S. performed the search and formulated the search terms together with C.B. and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. P.L. conceptualized the study, supported the analysis and data visualization, was the main supervisor, and participated in writing and editing the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author in response to a reasonable request.

References

- 1.Adamić A, Šlaus M. Comparative analysis of dental health in two archaeological populations from Croatia: The late medieval Dugopolje and early modern Vlach population from Koprivno. Bull Int Ass Paleodont. 2017;11((1)):11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler C, Dobney K, Weyrich LS, Kaidonis J, Walker AW, Haak W, Bradshaw CJ, et al. Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the neolithic and industrial revolutions. Nature Genetics. 2003;45((4)):450–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angel JL. The bases of paleodemography. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1969;30((3)):427–37. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330300314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arcini C, Plura CB, Nordin P. A garrison cemetery. Int J Histor Archaeol. 2020;24((1)):203–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold WH, Naumova EA, Koloda VV, Gaengler P. Tooth wear in two ancient populations of the Khazar Kaganat region in the Ukraine. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2007;17((1)):52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck J, Díaz-Zorita Bonilla M, Bocherens H, Díaz-del-Río P. Feeding a third millennium BC mega-site: bioarchaeological analyses of palaeodiet and dental disease at Marroquíes (Jaén, Spain) J Anthropol Archaeol. 2018;52:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennike P. An anthropological study of the skeletal remains of vikings from Langeland. In: Grøn O, EH Krag, Bennike P, editors. Vikingetidsgravpladser på Langeland. Rudkøbing: Langelands museum; 1994. pp. p. 168–83. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertilsson C, Sten S, Andersson J, Lundberg B, Lingström P. Dental health of vikings from kopparsvik on gotland. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2020;30((4)):551–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertilsson C, Nylund L, Vretemark M, Lingstrom P. Dental markers of biocultural sex differences in an early modern population from Gothenburg, Sweden: caries and other oral pathologies. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21((1)):304. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01667-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonsall LA. Comparison of female and male oral health in skeletal populations from late Roman Britain: implications for diet. Arch Oral Biol. 2014;59((12)):1279–300. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonsall LA, Pickard C. Stable isotope and dental pathology evidence for diet in late Roman Winchester, England. J Archaeological Sci Rep. 2015;2:128–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapple IL, Bouchard P, Cagetti MG, Campus G, Carra MC, Cocco F, et al. Interaction of lifestyle, behaviour or systemic diseases with dental caries and periodontal diseases: consensus report of group 2 of the joint EFP/orCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:39–51. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chazel JC, Valcarcel J, Tramini P, Pelissier B, Mafart B. Coronal and apical lesions, environmental factors: Study in a modern and an archeological population. Clin Oral Investig. 2005;9((3)):197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00784-005-0318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cucina A, Vargiu R, Mancinelli D, Ricci R, Santandrea E, Catalano P, et al. The necropolis of Vallerano (Rome, 2nd-3rd century AD): an anthropological perspective on the ancient Romans in the Suburbium. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2006;16((2)):104–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Djurić Srejić M. Dental paleopathology in a Serbian Medieval population. Anthropol Anz. 2001;59((2)):113–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durić M, Rakocević Z, Tuller H. Factors affecting postmortem tooth loss. J Forensic Sci. 2004;49((6)):1313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esclassan R, Grimoud AM, Ruas MP, Donat R, Sevin A, Astie F, et al. Dental caries, tooth wear and diet in an adult medieval (12th-14th century) population from mediterranean France. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54((3)):287–97. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez-Martinez P, Maurer AF, Jiménez-Morillo NT, Botella M, Lopez B, Dias CB. Bone stable isotope data of the late Roman population: a dietary reconstruction in a Roman villa context of South-Eastern Spain. J Archaeol Sci, Reports. 2020;33 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Formicola V. Neolithic transition and dental changes: the case of an Italian site. J Hum Evol. 1987;16((2)):231–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forshaw R. Dental indicators of ancient dietary patterns: dental analysis in archaeology. Br Dent J. 2004;216:529–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frayer DW. The dental remains from Krskany (Slovakia) and Vedrovice (Czech Republic) Anthropologie. 2004;42((1)):71–103. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuss J, Uhlig G, Böhme M. Earliest evidence of caries lesion in hominids reveal sugar-rich diet for a middle miocene dryopithecine from europe. PLoS One. 2018;13((8)):E0203307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garłowska E. Disease in the neolithic population of the Lengyel culture (4300–4000 B.C.) from the Kujawy region in north-central Poland. Z Morphol Anthrop. 2001;83((1)):43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gawlikowska-Sroka A, Dąbrowski P, Szczurowski J, Staniowski T. Analysis of interaction between nutritional and developmental instability in mediaeval population in Wrocław. Anthropol Rev. 2013;76((1)):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geber J, Murphy E. Dental markers of poverty: Biocultural deliberations on oral health of the poor in mid-nineteenth-century Ireland. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2018;167((4)):840–55. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giuffra V, Milanese M, Minozzi S. Dental health in adults and subadults from the 16th-century plague cemetery of Alghero (Sardinia, Italy) Arch Oral Biol. 2020;120:104928. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gualandi PB. Food habits and dental disease in an iron-age population. Anthropol Anz. 1992;50((1-2)):67–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hillson S. Recording dental caries in archaeological human remains. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2001;11((4)):249–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jílková M, Jílková M, Butenko T, Loboda T, Golli T, Fuchsová P, et al. Early medieval diet in childhood and adulthood and its reflection in the dental health of a Central European population (Mikulčice, 9th–10th centuries, Czech Republic) Arch Oral Biol. 2019;107:104526. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.104526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karsten JK, Heins SE, Madden GD, Sokhatskyi MP. Dental health and the transition to agriculture in prehistoric Ukraine: a Study of Dental Caries. Eur J. Archaeol. 2015;18((4)):562–79. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kashket S, Yaskell T, Murphy JE. Delayed effect of wheat starch in foods on the intraoral demineralization of enamel. Caries Res. 1994;28((4)):291–6. doi: 10.1159/000261988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W, et al. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94((5)):650–8. doi: 10.1177/0022034515573272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keenleyside A. Dental pathology and diet at apollonia, a Greek colony on the black Sea. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2008;18((3)):262–79. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerr NW, Bruce MF, Cross JF. Caries experience in the permanent dentition of late Mediaeval Scots (1300-1600 A.D.) Arch Oral Biol. 1988;33((3)):143–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(88)90038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr NW, Bruce MF, Cross JF. Caries experience in Mediaeval Scots. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1990;83((1)):69–76. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330830108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanfranco L, Eggers S. Caries Through Time: An Anthropological Overview. In: Li MY, editor. Contemporary Approach to Dental Caries. London: IntechOpen; 2012. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/32161. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen CS. Bioarchaeology: the lives and lifestyles of past people. J Archaeol Res. 2002;10((2)):119–66. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liebe-Harkort C. Exceptional rates of dental caries in a Scandinavian early iron age population: a Study of Dental Pathology at Alvastra, Östergötland, Sweden. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2012;22((2)):168–84. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liebe-Harkort C, Astvaldsdottir A, Tranaeus S. Quantification of dental caries by osteologists and odontologists: a Validity and Reliability Study. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2010;20((5)):525–39. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lillie M. Vedrovice: demography and palaeopathology in an early farming population. Anthropologie. 2008;46((2)):135–52. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lingström P, Borrman H. Distribution of dental caries in an early 17th century Swedish population with special reference to diet. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 1999;9((6)):395–403. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lingström P, van Houte J, Kashket S. Food starches and dental caries. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2000;11:366–80. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez B, Pardiñas AF, Garcia-Vazquez E, Dopico E. Socio-cultural factors in dental diseases in the medieval and early modern age of northern Spain. Homo. 2012;63((1)):21–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jchb.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.López-Morago C, José Estévez E, Alemán I, Bottela M. Dental health and diet in a medieval Muslim population from southern Spain. Anthropologie. 2020;58((1)):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lucas S, Sevin A, Passarius O, Esclassan R, Crubezy E, Grimoud AM. Study of Dental Caries and Periapical Lesions in a mediaeval population of the southwest France: differences in visual and radiographic inspections. HOMO. 2010;61((5)):359–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jchb.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lunt DA. The prevalence of dental caries in the permanent dentition of Scottish prehistoric and mediaeval populations. Arch Oral Biol. 1974;19((6)):431–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(74)90148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malčić AI, Vodanović M, Matijević J, Mihelić D, Mehičić GP, Krmek SJ. Caries prevalence and periodontal status in 18th century population of Požega-Croatia. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56((12)):1592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manzi G, Salvadei L, Vienna A, Passarello P. Discontinuity of life conditions at the transition from the roman imperial age to the early middle ages: Example from central Italy evaluated by pathological dento-alveolar lesions. Am J Hum Biol. 1999;11((3)):327–41. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(1999)11:3<327::AID-AJHB5>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marin V, Hrvoje B, Mario S, Željko D. The frequency and distribution of caries in the mediaeval population of Bijelo Brdo in Croatia (10th-11th century) Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50((7)):669–80. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masotti S, Onisto N, Marzi M, Gualdi-Russo E. Dento-alveolar features and diet in an Etruscan population (6th-3rd c. B.C.) from northeast Italy. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58((4)):416–26. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masotti S, Varalli A, Goude G, Moggi-Cecchi J, Gualdi-Russo E. A combined analysis of dietary habits in the Bronze Age site of Ballabio (northern Italy) Archaeol Anthropol Sci. 2019;11((3)):1029–47. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mays S. The effect of factors other than age upon skeletal age indicators in the adult. Ann Hum Biol. 2015;42((4)):332–41. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2015.1044470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McKenzie J, Murphy EM, Guiry E, Donnelly CJ, Beglanef F. Diet in medieval gaelic Ireland: a Multiproxy Study of the human remains from Ballyhanna, Co. Donegal. J Archaeol Sci. 2020;121:105203. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meinl A, Rottensteiner GM, Huber CD, Tangl S, Watzak G, Watzek G. Caries frequency and distribution in an early medieval Avar population from Austria. Oral Dis. 2010;16((1)):108–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michael DE, Manolis SK. Using dental caries as a nutritional indicator, in order to explore potential dietary differences between sexes in an ancient Greek population. Mediterr Archaeol Archaeom. 2014;14((2)):237–48. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michael DE, Eliopoulos C, Manolis SK. Exploring sex differences in diets and activity patterns through dental and skeletal studies in populations from ancient Corinth, Greece. Homo. 2017;68((5)):378–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jchb.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michael DE, Iliadis E, Manolis SK. Using dental and activity indicators in order to explore possible sex differences in an adult rural medieval population from Thebes (Greece) Anthropol Rev. 2017;80((4)):427–47. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miclon V, Gaultier M, Genies C, Cotté O, Yvernault F, Herrscher E. Social characterization of the medieval and modern population from Joué-lès-Tours (France): Contribution of oral health and diet. Bull Mem Soc Anthropol Paris. 2019;31((1)):77–92. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miliauskienė R, Jankauskas R. Social differences in oral health: dental status of individuals buried in and around Trakai Church in Lithuania (16th–17th c.c.) Anthropol Anz. 2015;72((1)):89–106. doi: 10.1127/anthranz/2014/0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;21:6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Müller A, Hussein K. Meta-analysis of teeth from European populations before and after the 18th century reveals a shift towards increased prevalence of caries and tooth loss. Arch Oral Biol. 2017;73:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Norderyd O, Kochi G, Papias A, Köhler AA, Helkimo AN, Brahm CO, et al. Oral health of individuals aged 3–80 years in Jönköping, Sweden during 40 years (1973–2013) Swed Dent J. 2015;39:69–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Novak M. Dental health and diet in early medieval Ireland. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60((9)):1299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olsson G, Sagne S. Studies of caries prevalence in a medieval population. Dentomaxillofac radiol. 1976;5((1–2)):12–8. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.1976.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peko D, Vodanović M. Acta Med-Hist Adriat. 2016;14((1)):41–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petersone-Gordina E, Roberts C, Millard AR, Montgomery J, Gerhards G. Dental disease and dietary isotopes of individuals from St Gertrude Church cemetery, Riga, Latvia. PLoS One. 2018;13((1)):e0191757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quade L, Binder M. Life on a Napoleonic battlefield: a bioarchaeological analysis of soldiers from the Battle of Aspern, Austria. Int J Paleopathol. 2018;22:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpp.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Radović M, Stefanović S. The bioarchaeology of the Neolithic transition: evidence of dental pathologies at Lepenski Vir (Serbia) Documenta Praehistorica. 2013;40((1)):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seiler R, Piombino-Mascali D, Rühli F. Dental investigation of mummies from the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo (circa 18th–19th century CE) HOMO. 2017;68((4)):274–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jchb.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369((9555)):51–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Šikanjić PR. Analysis of human skeletal remains from Nadin iron age burial mound. Coll Antropol. 2006;30((4)):795–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silvana M, Borgognini T, Elena R. Dietary patterns in the mesolithic samples from Uzzo and Molara caves (Sicily): the evidence of teeth. J Hum Evol. 1985;14((3)):241–54. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Šlaus M. Biocultural analysis of sex differences in mortality profiles and stress levels in the late medieval population from Nova Raca, Croatia. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2000;111((2)):193–209. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200002)111:2<193::AID-AJPA6>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Šlaus M, Pećina-Hrncević A, Jakovljević G. Dental disease in the late Medieval population from Nova Raca, Croatia. Coll Antropol. 1997;21((2)):561–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Šlaus M, Bedić Z, Rajić Šikanjić P, Vodanović M, Domić Kunić A. Dental health at the transition from the late antique to the early medieval period on Croatia's eastern Adriatic coast. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2011;21((5)):577–90. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Šlaus M, Bedić Ž, Bačić A, Bradić J, Vodanović M, Brkić H. Endemic warfare and dental health in historic period archaeological series from Croatia. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2018;28((1)):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith JS. Archaeological oral health: a comparison of post-medieval and modern-day dental caries exposure of adults in East London. Br Dent J. 2019;227((8)):721–5. doi: 10.1038/s41415-019-0737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Swales DM. A biocultural analysis of mortuary practices in the later anglo‐saxon to anglo‐norman black gate cemetery, newcastle-upon-tyne, England. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2019;29((2)):198–219. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thornton F. Dental disease in a Romano-British skeletal population from Baldock, Hertfordshire. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 1991;1((3)):273–7. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Topić B, Raščić-Konjhodžić H, Cižek Sajko M. Periodontal disease and dental caries from Krapina Neanderthal to contemporary man: Skeletal Studies. Acta Med Acad. 2012;41((2)):119–30. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trombley TM, Agarwal SC, Beauchesne PD, Goodson C, Candilio F, Coppa A, et al. Making sense of medieval mouths: Investigating sex differences of dental pathological lesions in a late medieval Italian community. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2019;169((2)):253–69. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ubelaker DH, Pap I. Human skeletal biology from the arpádian age of Northeastern Hungary. Anthropologie. 2008;46((1)):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ubelaker DH, Ross AH, Zarenko KM. Dental disease in nineteenth century Spain. Anthropologie. 2009;47((3)):273–82. [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Houte J. Role of micro-organisms in caries etiology. J Dent Res. 1994;73:672–81. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730031301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Varrela TM. Prevalence and distribution of dental caries in a late medieval population in Finland. Arch Oral Biol. 1991;36((8)):553–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(91)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vilkama R, Kylli R, Salmi A-K. Sugar consumption, dental health and foodways in late medieval iin hamina and early modern oulu, northern Finland. Scand J Hist. 2016;41((1)):2–31. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Walter BS, DeWitte SN, Redfern RC. Sex differentials in caries frequencies in Medieval London. Arch Oral Biol. 2016;63:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Watt ME, Lunt DA, Gilmour WH. Caries prevalence in the permanent dentition of a mediaeval population from the south-west of Scotland. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42((9)):601–20. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(97)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wells C. Dental pathology from a Norwich, Norfolk, Burial ground. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1968;23((4)):372–9. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/xxiii.4.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whittaker DK, Molleson T. Caries prevalence in the dentition of a late eighteenth century population. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41((1)):55–61. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(95)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wittwer-Backofen U, Tomo N. In: The neolithic demographic transition and its consequences. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2008. From health to civilization stress? In search for (of?) traces of a health transition during the warly neolithic (age?) in Europe; pp. p. 501–38. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yanko NV, Artemyev AV, Kaskova LF. Dental health indicators of the chernyakhov population from shyshaki (Ukraine) Anthropol Rev. 2021;84((1)):17–28. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author in response to a reasonable request.