Abstract

Background

People with no previous cardiovascular events or cardiovascular disease represent a primary prevention population. The benefits and harms of treating mild hypertension in primary prevention patients are not known at present. This review examines the existing randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence.

Objectives

Primary objective: To quantify the effects of antihypertensive drug therapy on mortality and morbidity in adults with mild hypertension (systolic blood pressure (BP) 140‐159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 90‐99 mmHg) and without cardiovascular disease.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013 Issue 9, MEDLINE (1946 to October 2013), EMBASE (1974 to October 2013), ClinicalTrials.gov (all dates to October 2013), and reference lists of articles. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) were searched for previous reviews and meta‐analyses of anti‐hypertensive drug treatment compared to placebo or no treatment trials until the end of 2011.

Selection criteria

RCTs of at least 1 year duration.

Data collection and analysis

The outcomes assessed were mortality, stroke, coronary heart disease (CHD), total cardiovascular events (CVS), and withdrawals due to adverse effects.

Main results

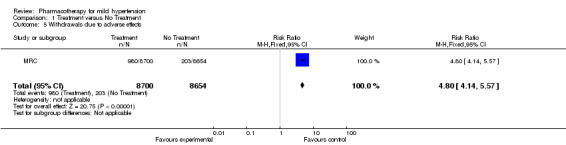

Of 11 RCTs identified 4 were included in this review, with 8,912 participants. Treatment for 4 to 5 years with antihypertensive drugs as compared to placebo did not reduce total mortality (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.63, 1.15). In 7,080 participants treatment with antihypertensive drugs as compared to placebo did not reduce coronary heart disease (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.80, 1.57), stroke (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.24, 1.08), or total cardiovascular events (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.72, 1.32). Withdrawals due to adverse effects were increased by drug therapy (RR 4.80, 95%CI 4.14, 5.57), Absolute risk increase (ARI) 9%.

Authors' conclusions

Antihypertensive drugs used in the treatment of adults (primary prevention) with mild hypertension (systolic BP 140‐159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 90‐99 mmHg) have not been shown to reduce mortality or morbidity in RCTs. Treatment caused 9% of patients to discontinue treatment due to adverse effects. More RCTs are needed in this prevalent population to know whether the benefits of treatment exceed the harms.

Plain language summary

Benefits of antihypertensive drugs for mild hypertension are unclear

Individuals with mildly elevated blood pressures, but no previous cardiovascular events, make up the majority of those considered for and receiving antihypertensive therapy. The decision to treat this population has important consequences for both the patients (e.g. adverse drug effects, lifetime of drug therapy, cost of treatment, etc.) and any third party payer (e.g. high cost of drugs, physician services, laboratory tests, etc.). In this review, existing evidence comparing the health outcomes between treated and untreated individuals are summarized. Available data from the limited number of available trials and participants showed no difference between treated and untreated individuals in heart attack, stroke, and death. About 9% of patients treated with drugs discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. Therefore, the benefits and harms of antihypertensive drug therapy in this population need to be investigated by further research.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Antihypertensive drug therapy compared with placebo for mild hypertension | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Adults with mild hypertension and no cardiovascular disease Settings: ambulatory Intervention: Stepped care antihypertensive drug therapy Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Antihypertensive drugs | |||||

|

Mortality 4 to 5 years |

Low risk population | RR 0.85 (0.63 to 1.15) | 8912 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | More RCTs needed as a significant benefit may have been missed. | |

| 15 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (9 to 17) | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| 30 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (18 to 34) | |||||

|

Total CV events 5 years |

Low risk population | RR 0.97 (0.72 to 1.32) | 7080 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | More RCTs needed as wide confidence intervals are consistent with a significant benefit or a significant harm. | |

| 15 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (11 to 20) | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| 30 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (22 to 40) | |||||

|

Withdrawals due to adverse effects 5 years |

Low risk population | RR 4.80 (4.14 to 5.57) | 17,354 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Withdrawals due to adverse effects are increased. It was downgraded to moderate as it was not limited to a primary prevention population with mild hypertension. | |

| 15 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (62 to 84) | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| 30 per 1000 | 144 per 1000 (124 to 168) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

The median control group risk was derived from the event rate in the control group i.e. 20 per 1000 mortality, 24 per 1000 total CV events and 23 per 1000 withdrawals due to adverse effects.

Background

Previous meta‐analyses have concluded that cardiovascular events and overall mortality are decreased with antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to placebo or no treatment (Collins 1990, Gueyffier 1996, Psaty 1997, Wright 1999, Quan 2000, Psaty 2003, Wright 2009). These meta‐analyses have combined subjects with mild elevations of blood pressure (stage 1), 140‐159/ 90‐99 mmHg, and moderate to severe elevations of blood pressure (> 160/100 mmHg). These meta‐analyses have also combined patients who have had a previous cardiovascular event (secondary prevention) with subjects who have not had a cardiovascular event (primary prevention). It is commonly assumed that the treatment effect expressed as relative risk is the same for primary prevention and secondary prevention populations; however, this is not proven. Furthermore, it is expected that the absolute risk reduction would be larger in secondary prevention populations than in primary prevention populations.

At the present time, individuals with mild elevations of blood pressure and no cardiovascular disease (primary prevention) are commonly treated with antihypertensive drugs despite there being no direct evidence supporting this practice. Furthermore this represents about half of the people presently being treated with antihypertensive drugs since the proportion of patients with mild elevations in blood pressure is about the same as the proportion with moderate to severe elevations in blood pressure (Marchant 2011). Therefore it is evident that there is a need to determine whether there is a proven reduction in mortality and morbidity with antihypertensive treatment in this patient group and if so the magnitude of that reduction. An attempt to do this by limiting to trials where patients were categorized as mild hypertension has been done (Therapeutics Initiative 2007), however in that analysis the average blood pressure at baseline was 160/98 mmHg, making it clear that even in that attempt about half of the individuals had moderate elevations of blood pressure at baseline. In that analysis antihypertensive treatment reduced total cardiovascular events, but not mortality. However, the findings of that analysis cannot be assumed to be extrapolated to the patients (about half of the total) that had mild elevations of blood pressure at baseline. The objective of this review was to assess the mortality and morbidity outcomes in randomized controlled trials using individual patient data whenever possible and limit the analysis to a primary prevention population with mild elevations of blood pressure at baseline.

Objectives

1. To quantify the effects of antihypertensive drug therapy as compared to no treatment on mortality and morbidity in healthy adults with mild elevations of blood pressure (systolic BP 140‐159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 90‐99 mmHg).

2. To quantify withdrawals due to adverse drug effects for antihypertensive drug therapy in healthy adults with mild hypertension.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials of at least 1 year duration.

Types of participants

A primary prevention population of men and non‐pregnant women, greater than 18 years of age with mild hypertension defined as a systolic blood pressure of 140 ‐ 159 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure 90 ‐ 99 mmHg and no evidence of cardiovascular disease at baseline: specifically defined as no myocardial infarction (MI), angina pectoris, coronary bypass surgery, coronary angioplasty, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, carotid endarterectomy, surgery for peripheral vascular disease, intermittent claudication, or renal failure (creatinine > 1.5 times the upper limit of normal). More than 80% of patients in a trial had to have mild hypertension as defined above for the trial to be included unless individual patient data was available allowing specific inclusion of this population as defined.

Types of interventions

Treatment with an antihypertensive drug either as monotherapy or with the addition of other drugs in a stepped care approach. Control: placebo or no antihypertensive treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Total mortality Total cardiovascular events (total stroke, total MI and total congestive heart failure CHF)

Secondary outcomes

Total stroke (fatal and nonfatal strokes) Total coronary heart disease (fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarction, sudden death)

Withdrawals due to adverse drug effects

Search methods for identification of studies

The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched to the end of 2011 for related reviews and meta‐analyses of anti‐hypertensive drug treatment compared to placebo or no treatment trials. Reports of relevant trials referred to in these reviews were obtained.

The following electronic databases were searched for primary studies: CENTRAL (2013, Issue 9), MEDLINE (1946 to October 2013), EMBASE (1974 to October 2013), ClinicalTrials.gov (all dates to October 2013), and reference lists of articles.

Electronic databases were searched using a strategy combining the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐maximizing version (2008 revision) with selected MeSH terms and free text terms relating to hypertension. No language restrictions were used. The MEDLINE search strategy (Appendix 1) was translated into EMBASE (Appendix 2), CENTRAL (Appendix 3), and Clinical Trials.gov (Appendix 4) using the appropriate controlled vocabulary as applicable.

Other sources:

a) Reference lists of all papers and relevant reviews identified

b) Authors of relevant papers were contacted regarding any further published or unpublished work

c) Authors of trials reporting incomplete information were contacted to provide the missing information

Data collection and analysis

All abstracts of trials identified by electronic searching or bibliographic scanning were screened. Those studies which appeared to meet the predetermined inclusion criteria stated above were selected on the basis of full text screening. When some trials also included subjects different than those of interest e.g.. secondary prevention, stage 2 hypertension, we attempted to get the data on the subjects with mild hypertension as defined in this review. Such information was available for a large number of subjects in the INDANA database primarily from the Australian trial (ANBP) in mild hypertension and the MRC trial in mild hypertension. Despite all efforts individual subject data were not available for the Oslo study, the USPHSHC study, and the VA‐NHLBI study. Data abstraction was undertaken by 2 independent reviewers who collected information on the following characteristics for each trial: type and dose of antihypertensive drugs used; other interventions used; patient characteristics, including co‐morbid conditions; morbidity and mortality outcomes; and length of trial follow‐up.

Risk of bias was also assessed independently by 2 reviewers using the risk of bias tool and the following criteria: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, Incomplete outcome data, selective reporting or other biases. Disagreements between independent reviewers arising in any of the stages above were resolved by a third reviewer (JMW).

Using the Cochrane software (RevMan) a quantitative analysis was carried out based on the availability of outcome data in the defined population. Individual patient data from 3 trials (ANBP; MRC; SHEP) and all data from 1 trial (VA‐NHLBI) were pooled. Meta‐analysis was performed using the Mantel‐Haenszel statistical method and a fixed effects model. The risk ratio of each outcome comparing treatment versus no treatment or placebo was calculated.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

We retrieved 11 studies where antihypertensive therapy was administered for primary prevention in subjects with mild hypertension, published between 1966 and 2005 (see Figure 1). We excluded 2 trials because they had 2 or fewer subjects who met the criteria outlined in this review (MRC2, COOPE) and 3 trials because they did not have a placebo or no‐treatment study group (HDFP, MRFIT, FEVER 2005). Despite considerable effort we were unable to obtain individual subject data for the Oslo, USPHSHC, and VA‐NHLBI studies (2,186 patients). Based on the baseline blood pressure and standard deviation, we established that more than 20% of the patients in the Oslo Study and the USPHSHC study had moderately elevated blood pressure. Therefore these trials were excluded as they could not be expected to reflect the effects in a primary prevention population with mild hypertension. In the VA‐NHLBI trial, less than 20% of subjects had moderately elevated blood pressure so we included this trial (1,012 patients). Individual subject data was obtained for ANBP, MRC, and SHEP trials and only those subjects who met the above stated criteria at baseline were included in this review (7,900 patients).The characteristics of these 4 included trials (8912 participants) in this review are summarized in the table Characteristics of included studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias from 5 domains was assessed for each of the included studies (see Risk of bias in included studies).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

For the 8912 participants included in this review, treatment with antihypertensive drugs as compared to no treatment did not reduce total mortality (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.63, 1.15). Furthermore, antihypertensive treatment did not significantly reduce total stroke (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.24, 1.08), total coronary heart disease (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.80, 1.57) or total cardiovascular events (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.72, 1.32) (see Data and analyses).

Withdrawals due to adverse effects (WDAEs) was only available from all patients in the MRC trials and not from the subgroup of patients with mild hypertension. Assuming that withdrawals due to adverse effects would be similar in the participants with mild hypertension and those with moderate to severe hypertension, we have calculated this value for the whole trial. This showed an increase in WDAEs with antihypertensive treatment RR 4.80 [4.14, 5.17], ARR 8.9%. The VA‐NHLBI trial reported any adverse symptom 1642/508 in the treatment group and 920/504 in the no treatment group. Chemical abnormalities such as hypokalaemia were also increased in the treatment group, 216 versus the control group, 15.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review demonstrates that antihypertensive drugs used in the treatment of patients without a previous cardiovascular event (primary prevention) with mild hypertension (systolic BP 140‐159 mmHg and / or diastolic BP 90‐99 mmHg) have not been proven to significantly reduce any outcome including total mortality, total cardiovascular events, coronary heart disease, or stroke. This review provides data on >8,000 people followed for 5 years and suggests little or no reduction in total cardiovascular events, RR 0.97 [0.72, 1.32] (see Table 1). The review also shows a non‐significant reduction in stroke, RR 0.51 [0.24, 1.08] and mortality 0.85 [0.63, 1.15] consistent with there being a real benefit of treatment, but that it wasn't demonstrable due to the paucity of events and people. Thus it remains possible, but highly unlikely, that there is an overall significant benefit of treating this group of patients with currently used medications.

However, even if the assumption is made, as is commonly done, that the relative benefits for a primary prevention population with mild hypertension are the same as for patients with moderate to severe hypertension, mortality RR 0.9 and total CV events RR 0.7 from the review of first‐line treatments of hypertension (Wright 2009) then the absolute benefits would be very small. We have made this estimate from the placebo group in the largest trial in this review (MRC). The estimated absolute risk reduction in this best case scenario is 0.25% for mortality and 0.78% for total cardiovascular events over a 5 year period. This means that 400 people would have to be treated for 5 years to prevent 1 death and 128 people would have to be treated for 5 years to prevent 1 cardiovascular event. It is likely that many such patients given this information would choose non drug treatments for hypertension (e.g. diet, exercise, stress management, etc.) rather than drug therapy. They would be even less likely to choose drug treatment when they were told that these estimated benefits are a best case scenario and uncertain based on the best available evidence at this time from this review. Furthermore they must also be told that they have a 9% chance of having an adverse effect that would require them to withdraw from therapy. Withdrawals may not be that high in practice today as lower doses of thiazides and beta‐blockers are used today than was used in the MRC trial.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The findings of this review are limited by the inability to get individual patient data from all the trials with patients in this subgroup. The number of patients in this review in comparison to the total number of patients in the trials in shown in Table 2. However, even if we had all the data there is a good chance the findings would remain uncertain and inconclusive. This is due to the fact that patients with mild hypertension have a relatively low risk of experiencing an adverse cardiovascular event in keeping with the low number of events that were seen in this review. A 5 year study with 15,000 patients would be required to demonstrate a reduction of 30% in total cardiovascular events and of 45,000 patients to demonstrate a mortality reduction of 10%. Planned subgroup analyses were not conducted due to the paucity of outcomes in the overall data.

1. Patient numbers in this review versus total numbers in the trials.

| Trials | This review | Total | ||

| Treatment | Placebo | Treatment | Placebo | |

| MRC | 3012 | 3049 | 8700 | 8654 |

| ANBP | 958 | 874 | 1721 | 1706 |

| SHEP | 3 | 4 | 2365 | 2371 |

| VA‐NHLBI | 508 | 504 | 508 | 504 |

| Total | 4481 | 4431 | 13294 | 13235 |

Quality of the evidence

The trials contributing to this review were funded by granting agencies. Nevertheless the risk of bias assessment suggests that there is a moderate to high risk of bias (Figure 2) making the magnitude of the non‐significant relative risk reduction more likely to be an overestimate than an underestimate. In particular the Australian trial (ANBP) had a high risk of ascertainment bias. As a result this trial only contributed to mortality data. The RR estimate of effect on mortality with treatment was unaffected by deselecting this trial. Another limitation is that most of the outcome data comes from the MRC trial, which we judged to have a high risk of detection bias and attrition bias. Despite the lack of financial bias in this trial the investigators were more likely to be biased in favour of treatment than against, justifying why the non‐significant benefits are likely to be an overestimate.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Potential biases in the review process

It is unlikely that any large unpublished negative trials have been missed. It is over 20 years now since it has been accepted by the medical community that patients with mild hypertension should be treated. Therefore it is highly unlikely that trials have been conducted in this population in the last 20 years. The inability to obtain individual patient data in all relevant trials could have biased the findings.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

As far as we are aware there have been no previous systematic reviews conducted to answer this question. The findings of this review are however in disagreement with hypertension guideline recommendations in the US, Canada and Europe. These guideline groups have recommended treatment of all adults with a blood pressure > 140/90 mmHg. The European Guidelines specify that the recommendation for pharmacologic treatment in "mild uncomplicated hypertension" is based on the outcomes of these 5 trials (ANBP; MRC; FEVER 2005; HDFP; Oslo). They do note that the evidence in favour of this recommendation is scant because older trials of "mild hypertension" treated patients whose blood pressure could be higher than grade 1 hypertension or included secondary prevention patients (Mancia 2009). We have excluded the latter 3 RCTs, FEVER 2005, HDFP and Oslo, because they had >20% of patients with moderate or higher blood pressure and FEVER 2005 plus HDFP did not have an appropriate control group. The American Society of Hypertension guidelines refers to the European Guidelines to justify this treatment threshold recommendation. The Canadian guidelines are not explicit as to how they come to their recommendations.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Since a large proportion of people treated with antihypertensive therapy are individuals with no previous cardiovascular disease (primary prevention) and mild elevations of blood pressure, the findings of this review have important implications. Most physicians have been treating such patients with false confidence that it was based on RCT evidence. Based on the best available evidence at the present time, this review does not show any significant benefit of antihypertensive drug therapy in reducing mortality, heart attacks, strokes, or overall cardiovascular events. Furthermore drug treatment caused 9% of patients to withdraw due to adverse effects. It is likely that given this evidence many individuals with no cardiovascular disease and mild hypertension would choose non‐drug treatments (diet, exercise, stress management, etc.) rather than drug therapy.

Implications for research.

Evidence based treatment of mild hypertension represents a challenge to the medical and research community. Hypertension, the commonest clinical condition being treated today is being treated with an assumption that it has been established that the benefits of treatment outweigh the harms, when that is not in fact the case for people with no cardiovascular disease (primary prevention) and mild hypertension. In the absence of evidence, it is entirely ethical to conduct a large RCT in primary prevention patients with mild hypertension comparing antihypertensive therapy with placebo. At the present time equipoise exists between the treated and the placebo group. In such an RCT it would be possible to compare the relative and absolute benefits and harms in people at baseline in the higher range 150‐159/95‐99 mmHg and in the lower range 140‐149/90‐94 mmHg. By following such an approach we may finally properly define hypertension as "that BP above which the benefits of treatment outweigh the harms".

Feedback

Should mild hypertension be treated? The possible benefits of angiotensin receptor blockers, 12 September 2012

Summary

We read with interest the manuscript of Diao D et al at about the possible benefits of treating mild hypertensive patients in primary prevention. (Diao 2012) In this study, 4 randomized clinical trials, with a total of 8,912 patients, were included for the analysis. After a follow‐up of 4‐5 years, antihypertensive treatment was not followed with a reduction of total mortality, coronary heart disease, stroke or total cardiovascular events. Even more, antihypertensive treatment was associated with an increased risk of withdrawals due to adverse effects.

Although the implications of this study are of great interest, the fact is it has important limitations that hamper its conclusions to be translated into clinical practice. Firstly, the relative small sample size, with less than 9,000 patients included. Indeed, not many studies have analyzed this population. By contrast, current outstanding clinical trials actually include a greater population to allow attaining clinically relevant conclusions (i.e. in LIFE, 9,193 patients were included (Dahlöf 2002), in ACCOMPLISH, 11,506 patients (Jamerson 2008). This is even more important taking into account that in these studies high risk hypertensive patients were included, with more expected outcomes. As cardiovascular risk lowers, more patients are required to really ascertain whether a treatment is effective or not.

Moreover, follow up was limited to 4 to 5 years in the included studies. However, in general, hypertension‐related organ damage needs time to establish and more time to develop cardiovascular complications. Moreover, this time is even longer in mild hypertension. Thus, to actually establish the real benefits of antihypertensive therapy in this population, longer follow‐up is warranted or at least, intermediate endpoints, such as left ventricular hypertrophy or microalbuminuria, should be analyzed (Mancia 2009).

Finally, it is also important to analyze the antihypertensive therapy used in the studies included in this meta‐analysis (ANBP: chlorothiazide, methyldopa, propranolol, or pindolol added as 2nd‐order treatment, and hydralazine or clonidine added as 3rd‐order treatment; control placebo; MRC: bendrofluazide, propranolol, methyldopa added if required; control placebo; SHEP: chlorthalidone, step 2 atenolol or reserpine; identical placebo; VA‐NHLBI: chlortalidone, reserpine; control placebo) (Diao D 2012). Many of these drugs are not currently being used. In fact, modern antihypertensive agents are more effective or better tolerated than those used in most of these studies.

On the other hand, beta blockers (present in all the analyzed studies) are commonly withdrawn due to side effects in a significant proportion of patients. This fact occurs even in secondary prevention (Gislason 2006). Medication adherence is important to assure the benefits of therapy during follow‐up. In fact, when the efficacy of 2 drugs is similar, the agent with lesser rates of side effects should be chosen. For example, in the ONTARGET trial, although telmisartan and ramipril similarly reduced cardiovascular outcomes, when discontinuation of study medication was included in the analysis, a trend to lesser outcomes was observed with telmisartan (Barrios 2008). If using drugs with lower side effects is important in secondary prevention, this is even more relevant in primary prevention where patients do not have symptoms. With regard to first‐line current antihypertensive drugs (diuretics, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers), it seems that angiotensin receptor blockers could be the better tolerated agents.

Although specific and appropriate clinical trials are needed to ascertain the benefits of antihypertensive therapy in patients with mild hypertension, it should be currently recommended to reduce blood pressure values to established targets in patients with mild hypertension, but with those drugs better tolerated.

References

Barrios V, Escobar C, Prieto L, Herranz I. Adverse events in clinical trials: is a new approach needed? Lancet. 2008;372(9638):535‐6.

Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 2002;359(9311):995–1003.

Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, Gueyffier F. Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD006742.

Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrøm SZ, Gadsbøll N, Buch P, Friberg J, Rasmussen S, Køber L, Stender S, Madsen M, Torp‐Pedersen C. Long‐term compliance with beta‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(10):1153‐8.

Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlöf B, Pitt B, Shi V, Hester A, Gupte J, Gatlin M, Velazquez EJ; ACCOMPLISH Trial Investigators. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2417‐28.

Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti‐Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Burnier M, Caulfield MJ, Cifkova R, Clément D, Coca A, Dominiczak A, Erdine S, Fagard R, Farsang C, Grassi G, Haller H, Heagerty A, Kjeldsen SE, Kiowski W, Mallion JM, Manolis A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson P, Olsen MH, Rahn KH, Redon J, Rodicio J, Ruilope L, Schmieder RE, Struijker‐Boudier HA, van Zwieten PA, Viigimaa M, Zanchetti A; European Society of Hypertension. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens. 2009;27(11):2121‐58.

We agree with the conflict of interest statement below: We certify that we have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of our feedback.

Reply

We thank Drs. Barrios and Escobar for their comments.

Regarding the number of RCT participants included in this systematic review (n=8,912), we agree that it would be good if there were more data, however, this review does represent all the participants and data that are available at this time. Thus at the present time we do not have proof that the benefits of drug treatment outweigh the harms for primary prevention patients with mild elevations in blood pressure, a group that represents half of the hypertensive population.

We agree with Barrios and Escobar's conclusions that "specific and appropriate clinical trials are needed to ascertain the benefits of antihypertensive therapy in patients with mild hypertension". However, we disagree with their conclusions that "it should be currently recommended to reduce blood pressure values to established targets in patients with mild hypertension, but with those drugs better tolerated". Widespread treatment in the absence of evidence is never a good approach. Patients who are offered drug treatment need to be told that drug treatment has not been proven to be beneficial.

Contributors

Vivencio Barrios <vbarriosa@medynet.com> and Carlos Escobar Affiliation: Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, Spain and Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain Role: Cardiologists

The results of this review should be interpreted (appropriately) as subgroup analyses, 15 November 2013

Summary

The review authors have addressed an important question: Do the benefits of antihypertensive drugs outweigh the downsides for healthy individuals with mild hypertension? To answer this question, the authors have conducted subgroup analyses. Their implicit question is whether the relative effects for mild hypertension are different from the relative effects for moderate and severe hypertension. However, they do not present or interpret their findings as subgroup analyses – we think they should. They also do not provide a biological rationale or indirect evidence to support an assumption that the relative effects are different. For example, only one trial in the review contributed data on strokes as an outcome. The effect estimate in that trial was a 50% relative risk reduction (RR 0.51) with a 95% confidence interval that included no effect (95% CI 0.24 to 1.08). The review authors interpret this as meaning “treatment with antihypertensive drugs as compared to placebo did not reduce” stroke. We disagree with this interpretation, which in our view confuses inconclusive evidence (from this subgroup analysis) with evidence of no effect (1). Given overlapping confidence intervals for the subgroup effects and the overall effects across people with different degrees of hypertension (a high likelihood that chance explains any apparent subgroup differences), and taking into consideration other criteria for assessing the credibility of subgroup effects (2), a reasonable conclusion is that the relative effectiveness of blood pressure lowering medication is likely the same across patients with different degrees of hypertension. Indirect evidence from observational studies of hypertension as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease also support this interpretation, since the risk seems to be proportional with the level of blood pressure, with no clear lower threshold (3). The absolute effects on cardiovascular outcomes, and therefore the net benefit from treating hypertension with medication is less for patients with mild hypertension than it is for patients with moderate or severe hypertension. On that basis there are good reasons to question the value of drug treatment for patients with mild hypertension. However, this is because of a lower baseline risk for cardiovascular events, not because of a smaller relative effect. Our interpretation of the subgroup analyses presented in this review is that treatment decisions should be based on the overall estimate of the relative effect, not on the estimates from these subgroup analyses (4). 1.Results should not be reported as statistically significant or statistically non‐significant. Oslo: Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC), Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2013. 2.Sun X, Briel M, Walter SD, Guyatt GH. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. Bmj. 2010;340:c117. PubMed PMID: 20354011. 3.MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990 Mar 31;335(8692):765‐74. PubMed PMID: 1969518. 4.Oxman AD. Subgroup analyses. Bmj. 2012;344:e2022. PubMed PMID: 22422834. We agree with the conflict of interest statement below: We certify that we have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of our feedback.

Reply

We thank Fretheim and Oxman for their comments on our review.

Historically, the benefit from drug treatment of hypertension has been demonstrated in predominantly moderate to severe hypertensive populations. Despite that recommendations have progressively extended the population to be treated from severe hypertension to moderate hypertension and then to mild hypertension (140‐159/90‐99 mmHg). Mild hypertension represents a very large group of people, approximately half of the people labeled as having hypertension. It is thus vitally important to look at the level of evidence within that sub‐group. The conclusion of the review is that there is a lack of evidence in this sub‐group, despite its numerical importance.

The interpretation proposed by Fretheim and Oxman is focused on the question whether there is evidence of differences between relative risk in mild hypertension compared to moderate to severe hypertension, i.e. the usual way to look at sub‐group analyses. They limit their comments to the case of stroke, which we agree does not suggest evidence for a difference. However, other outcomes such as MI or total cardiovascular disease events display different results with average effect estimates in mild hypertension outside of the CI of the average effects in more severe hypertension.

We agree with the conclusion of Fretheim and Oxman: "The absolute effects on cardiovascular outcomes, and therefore the net benefit from treating hypertension with medication is less for patients with mild hypertension than it is for patients with moderate or severe hypertension. On that basis there are good reasons to question the value of drug treatment for patients with mild hypertension." We would change the rationale for that statement to: “This is because of a lower baseline risk for cardiovascular events, and also because of important uncertainties regarding the specific relative effect of treatment in this subgroup.”

Contributors

Name: Atle Fretheim and Andrew D. Oxman Email Address: atle.fretheim@nokc.no Affiliation: Global Health Unit, Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 December 2013 | Feedback has been incorporated | Comment: The results of this review should be interpreted (appropriately) as subgroup analyses |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2007 Review first published: Issue 8, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 September 2012 | Feedback has been incorporated | Comment: Should mild hypertension be treated? |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Doug Salzwedel for helping with the search strategy used in this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present with Daily Update Search Date: 16 October 2013 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp thiazides/ 2 exp sodium potassium chloride symporter inhibitors/ 3 ((loop or ceiling) adj diuretic?).tw. 4 (amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide?).tw. 5 (chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide).tw. 6 or/1‐5 7 exp angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors/ 8 ((angiotensin$ or kininase ii or dipeptidyl$) adj3 (convert$ or enzyme or inhibit$ or recept$)).tw. 9 (ace adj3 inhibit$).tw. 10 acei.tw. 11 exp enalapril/ 12 (alacepril or altiopril or benazepril or captopril or ceronapril or cilazapril or delapril or enalapril or fosinopril or idapril or imidapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or pentopril or perindopril or quinapril or ramipril or spirapril or temocapril or trandolapril or zofenopril or aliskiren or enalkire or remikiren).tw. 13 or/7‐12 14 exp Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Blockers/ 15 exp losartan/ 16 (KT3‐671 or candesartan or eprosartan or irbesartan or losartan or olmesartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan).tw. 17 (angiotensin$ adj4 receptor$ adj3 (antagon$ or block$)).tw. 18 or/14‐17 19 exp calcium channel blockers/ 20 (calcium channel block$ or amlodipine or amrinone or bencyclane or bepridil or cinnarizine or conotoxins or diltiazem or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lidoflazine or magnesium sulfate or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or verapamil or omega‐agatoxin iva or omega‐conotoxin gvia or omega‐conotoxins).tw. 21 (calcium adj2 (inhibit$ or antagonist? or block$)).tw. 22 or/19‐21 23 (methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa).mp. 24 (reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil).mp. 25 (clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets).mp. 26 exp hydralazine/ 27 (hydralazin$ or hydrallazin$ or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat).tw. 28 or/23‐27 29 exp adrenergic beta‐antagonists/ 30 adrenergic beta antagonist?.tw. 31 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw. 32 (beta adj2 (antagonist? or receptor? or adrenergic? block$)).tw. 33 or/29‐32 [BBs] 34 exp adrenergic alpha antagonists/ 35 (alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin).tw. 36 (andrenergic adj2 (alpha or antagonist?)).tw. 37 ((andrenergic or alpha or receptor?) adj2 block$).tw. 38 or/34‐37 39 hypertension/ 40 hypertens$.tw. 41 ((high or elevat$ or rais$) adj2 blood pressure).tw. 42 or/39‐41 43 randomized controlled trial.pt. 44 controlled clinical trial.pt. 45 randomized.ab. 46 placebo.ab. 47 dt.fs. 48 randomly.ab. 49 trial.ab. 50 groups.ab. 51 or/43‐50 52 animals/ not (humans/ and animals/) 53 Pregnancy/ or Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced/ or Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular/ or exp Ocular Hypertension/ 54 (pregnancy‐induced or ocular hypertens$ or preeclampsia or pre‐eclampsia).ti. 55 51 not (52 or 53 or 54)

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

Database: Embase <1974 to 2013 Week 41> Search Date: 16 October 2013 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp thiazide diuretic agent/ 2 exp loop diuretic agent/ 3 ((loop or ceiling) adj diuretic?).tw. 4 (amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide?).tw. 5 (chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide).tw. 6 or/1‐5 7 exp dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase inhibitor/ 8 angiotensin converting enzyme inhibit$.tw. 9 (ace adj2 inhibit$).tw. 10 acei.tw. 11 (alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceranapril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or derapril or enalapril or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fosinopril or foroxymithine or gemopatrilat or idapril or imidapril or indolapril or libenzapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or omapatrilat or pentopril$ or perindopril$ or pivopril or quinapril$ or ramipril$ or rentiapril or saralasin or s nitrosocaptopril or spirapril$ or temocapril$ or teprotide or trandolapril$ or utibapril$ or zabicipril$ or zofenopril$).tw. 12 or/7‐11 13 exp angiotensin receptor antagonist/ 14 (angiotensin adj3 (receptor antagon$ or recetor block$)).tw. 15 arb?.tw. 16 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan).tw. 17 or/13‐16 18 calcium channel blocking agent/ 19 (amlodipine or amrinone or aranidipine or barnidipine or bencyclane or benidipine or bepridil or cilnidipine or cinnarizine or clentiazem or darodipine or diltiazem or efonidipine or elgodipine or etafenone or fantofarone or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lacidipine or lercanidipine or lidoflazine or lomerizine or manidipine or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or niguldipine or nilvadipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or semotiadil or terodiline or tiapamil or verapamil).tw. 20 (calcium adj2 (antagonist? or block$ or inhibit$)).tw. 21 or/18‐20 22 (methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa).mp. 23 (reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil).mp. 24 (clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets).mp. 25 hydralazine/ 26 (hydralazin$ or hydrallazin$ or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat).tw. 27 or/22‐26 28 exp beta adrenergic receptor blocking agent/ 29 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol).tw. 30 (beta adj2 (adrenergic? or antagonist? or block$ or receptor?)).tw. 31 or/28‐30 32 exp alpha adrenergic receptor blocking agent/ 33 (alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin).tw. 34 (andrenergic adj2 (alpha or antagonist?)).tw. 35 ((andrenergic or alpha or receptor?) adj2 block$).tw. 36 or/32‐35 37 exp hypertension/ 38 (hypertens$ or antihypertens$).tw. 39 ((high or elevat$ or rais$) adj2 blood pressure).tw. 40 or/37‐39 41 double blind$.mp. 42 placebo$.tw. 43 blind$.tw. 44 or/41‐43 45 (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) 46 Pregnancy/ or Hypertension, Pregnancy‐Induced/ or Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular/ or exp Ocular Hypertension/ 47 (pregnancy‐induced or ocular hypertens$ or preeclampsia or pre‐eclampsia).ti. 48 44 not (45 or 46 or 47) 49 (6 or 12 or 17 or 21 or 27 or 31 or 36) and 40 and 48

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on Wiley <Issue 9, 2013> Search Date: 16 October 2013 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on Wiley <Issue 9, 2013> Search Date: 16 October 2013 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ID Search #1 MeSH descriptor: [Thiazides] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Sodium Chloride Symporter Inhibitors] explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor: [Sodium Potassium Chloride Symporter Inhibitors] explode all trees #4 (loop or ceiling) next diuretic*:ti,ab #5 (amiloride or benzothiadiazine or bendroflumethiazide or bumetanide or chlorothiazide or cyclopenthiazide or furosemide or hydrochlorothiazide or hydroflumethiazide or methyclothiazide or metolazone or polythiazide or trichlormethiazide or veratide or thiazide*):ti,ab #6 (chlorthalidone or chlortalidone or phthalamudine or chlorphthalidolone or oxodoline or thalitone or hygroton or indapamide or metindamide):ti,ab #7 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 #8 MeSH descriptor: [Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibitors] explode all trees #9 "angiotensin converting enzyme" NEXT inhibit*:ti,ab #10 ace near/3 inhibit*:ti,ab #11 acei:ti,ab #12 (alacepril or altiopril or ancovenin or benazepril or captopril or ceranapril or ceronapril or cilazapril or deacetylalacepril or delapril or derapril or enalapril or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fosinopril or foroxymithine or gemopatrilat or idapril or imidapril or indolapril or libenzapril or lisinopril or moexipril or moveltipril or omapatrilat or pentopril* or perindopril* or pivopril or quinapril* or ramipril* or rentiapril or saralasin or s nitrosocaptopril or spirapril* or temocapril* or teprotide or trandolapril* or utibapril* or zabicipril* or zofenopril*):ti,ab #13 #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 #14 MeSH descriptor: [Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists] explode all trees #15 angiotensin near/3 (receptor NEXT antagon* or receptor NEXT block*):ti,ab #16 arb*:ti,ab #17 (abitesartan or azilsartan or candesartan or elisartan or embusartan or eprosartan or forasartan or irbesartan or losartan or milfasartan or olmesartan or saprisartan or tasosartan or telmisartan or valsartan or zolasartan):ti,ab #18 #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 #19 MeSH descriptor: [Calcium Channel Blockers] explode all trees #20 (amlodipine or amrinone or aranidipine or barnidipine or bencyclane or benidipine or bepridil or cilnidipine or cinnarizine or clentiazem or darodipine or diltiazem or efonidipine or elgodipine or etafenone or fantofarone or felodipine or fendiline or flunarizine or gallopamil or isradipine or lacidipine or lercanidipine or lidoflazine or lomerizine or manidipine or mibefradil or nicardipine or nifedipine or niguldipine or nilvadipine or nimodipine or nisoldipine or nitrendipine or perhexiline or prenylamine or semotiadil or terodiline or tiapamil or verapamil):ti,ab #21 calcium near/2 (antagonist* or block* or inhibit*):ti,ab #22 #19 or #20 or #21 #23 (methyldopa or alphamethyldopa or amodopa or dopamet or dopegyt or dopegit or dopegite or emdopa or hyperpax or hyperpaxa or methylpropionic acid or dopergit or meldopa or methyldopate or medopa or medomet or sembrina or aldomet or aldometil or aldomin or hydopa or methyldihydroxyphenylalanine or methyl dopa or mulfasin or presinol or presolisin or sedometil or sembrina or taquinil or dihydroxyphenylalanine or methylphenylalanine or methylalanine or alpha methyl dopa):ti,ab,kw #24 (reserpine or serpentina or rauwolfia or serpasil):ti,ab,kw #25 (clonidine or adesipress or arkamin or caprysin or catapres$ or catasan or chlofazolin or chlophazolin or clinidine or clofelin$ or clofenil or clomidine or clondine or clonistada or clonnirit or clophelin$ or dichlorophenylaminoimidazoline or dixarit or duraclon or gemiton or haemiton or hemiton or imidazoline or isoglaucon or klofelin or klofenil or m‐5041t or normopresan or paracefan or st‐155 or st 155 or tesno timelets):ti,ab,kw #26 MeSH descriptor: [Hydralazine] explode all trees #27 (hydralazin* or hydrallazin* or hydralizine or hydrazinophtalazine or hydrazinophthalazine or hydrazinophtalizine or dralzine or hydralacin or hydrolazine or hypophthalin or hypoftalin or hydrazinophthalazine or idralazina or 1‐hydrazinophthalazine or apressin or nepresol or apressoline or apresoline or apresolin or alphapress or alazine or idralazina or lopress or plethorit or praeparat):ti,ab,kw #28 #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 #29 MeSH descriptor: [Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists] explode all trees #30 (acebutolol or adimolol or afurolol or alprenolol or amosulalol or arotinolol or atenolol or befunolol or betaxolol or bevantolol or bisoprolol or bopindolol or bornaprolol or brefonalol or bucindolol or bucumolol or bufetolol or bufuralol or bunitrolol or bunolol or bupranolol or butofilolol or butoxamine or carazolol or carteolol or carvedilol or celiprolol or cetamolol or chlortalidone cloranolol or cyanoiodopindolol or cyanopindolol or deacetylmetipranolol or diacetolol or dihydroalprenolol or dilevalol or epanolol or esmolol or exaprolol or falintolol or flestolol or flusoxolol or hydroxybenzylpinodolol or hydroxycarteolol or hydroxymetoprolol or indenolol or iodocyanopindolol or iodopindolol or iprocrolol or isoxaprolol or labetalol or landiolol or levobunolol or levomoprolol or medroxalol or mepindolol or methylthiopropranolol or metipranolol or metoprolol or moprolol or nadolol or oxprenolol or penbutolol or pindolol or nadolol or nebivolol or nifenalol or nipradilol or oxprenolol or pafenolol or pamatolol or penbutolol or pindolol or practolol or primidolol or prizidilol or procinolol or pronetalol or propranolol or proxodolol or ridazolol or salcardolol or soquinolol or sotalol or spirendolol or talinolol or tertatolol or tienoxolol or tilisolol or timolol or tolamolol or toliprolol or tribendilol or xibenolol):ti,ab #31 beta near/2 (adrenergic* or antagonist* or block* or receptor*):ti,ab #32 #29 or #30 or #31 #33 MeSH descriptor: [Adrenergic alpha‐Antagonists] explode all trees #34 (alfuzosin or bunazosin or doxazosin or metazosin or neldazosin or prazosin or silodosin or tamsulosin or terazosin or tiodazosin or trimazosin):ti,ab #35 adrenergic near/2 (alpha or antagonist*):ti,ab #36 (adrenergic or alpha or receptor*) near/2 block*:ti,ab #37 #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 #38 MeSH descriptor: [Hypertension] this term only #39 hypertens*:ti,ab #40 (elevat* or high* or raise*) near/2 "blood pressure":ti,ab #41 #38 or #39 or #40 #42 (#7 or #13 or #18 or #22 or #28 or #32 or #37) and #41

Appendix 4. ClinicalTrials.gov

Database: ClinicalTrials.gov Search Date: 16 October 2013 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Search terms: randomized Study type: Interventional Studies Conditions: hypertension Interventions: antihypertensive Outcome Measures: blood pressure

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Treatment versus No Treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mortality | 4 | 8912 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.63, 1.15] |

| 2 Stroke | 3 | 7080 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.24, 1.08] |

| 3 Coronary Heart Disease | 3 | 7080 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.80, 1.57] |

| 4 Total CV events | 3 | 7080 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.72, 1.32] |

| 5 Withdrawals due to adverse effects | 1 | 17354 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.80 [4.14, 5.57] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus No Treatment, Outcome 1 Mortality.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus No Treatment, Outcome 2 Stroke.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus No Treatment, Outcome 3 Coronary Heart Disease.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus No Treatment, Outcome 4 Total CV events.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus No Treatment, Outcome 5 Withdrawals due to adverse effects.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

ANBP.

| Methods | Randomised single‐blind, comparing treatment with placebo. Trial conducted in Australia | |

| Participants | Ambulatory young patients, with mean age 50 years, range (30‐59 years). Australian (White) or European born, the former predominating. Male (63%). Baseline mean SBP/DBP was 157.4/100.4 mmHg. The inclusion criteria was SBP < 200 mmHg and DBP 90‐110 mmHg. Patients were followed for 4 years | |

| Interventions | Chlorothiazide 500mg once or twice daily, methyldopa, propranolol, or pindolol added as 2nd‐order treatment, and hydralazine or clonidine added as 3rd‐order treatment. Control: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Mortality, CHD, stroke, other CV events, systolic BP and diastolic BP | |

| Notes | Attrition bias for ANBPS trial : All components from the composite outcome were terminating events, without complementary mortality survey. All analyses regarding these separated components are subject to a censoring bias. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "patients randomly allocated, with stratification by age and sex" Not enough detail to know how this was done. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Trial was single blind so investigators physicians caring for the patient were not blinded as to treatment allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | All components from the composite outcome were terminating events, without complementary mortality survey. All analyses regarding these separated components are subject to a censoring bias |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified in report. |

MRC.

| Methods | Randomised single‐blind comparing 2 treatments and placebo | |

| Participants | Ambulatory patients, with mean age 52 years, range (35‐64 years). Ethnicity not reported. Male (52%). Baseline mean SBP/DBP was 161.4/98.2 mmHg and pulse pressure was 63 mmHg. The inclusion criteria was SBP < 200 mmHg and DBP 90‐109 mmHg. Patients were followed for 5 years | |

| Interventions | Bendrofluazide 10 mg daily (71% mono), Propranolol 80‐240 mg daily (78% mono), methyldopa added if required. Control: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Mortality, stroke, CHD, systolic BP and diastolic BP | |

| Notes | No CHF data | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomisation was in stratified blocks of eight within each sex, 10 year age group, and clinic." Sufficient detail provided to consider low risk. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Trial was single blind. Investigators knew what treatment the patients were receiving. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Myocardial infarction and stroke were reasons for terminating the study follow‐up, except for death flagging. This induces a censoring attrition bias, limited to the occurrence non‐fatal events myocardial infarction or stroke. In the original paper : TERMINATION OF PARTICIPATION IN TRIAL Events terminating a patient's participation were: stroke, whether fatal or non‐fatal; coronary events, including sudden death thought to be due to a coronary cause, death known to be due to myocardial infarction, and non‐fatal myocardial infarction; other cardiovascular events, including deaths due to hypertension (ICD 400‐404) and to rupture or dissection of an aortic aneurysm; and death from any other cause. Clinic staff reported these events to the coordinating centre. The records of all patients who suffered non‐fatal terminating events and of any others who lapsed from the trial, whatever the reason, were "flagged" at the Southport NHS central register to ensure notification of death.) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not described in report |

SHEP.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo controlled. Trial conducted in USA | |

| Participants | Ambulatory patients, with mean age 72 years, range (> 60 years). 13.9% of patients were African‐Americans. Male (43%). Baseline mean SBP/DBP was 170/77 mmHg and pulse pressure was 93 mmHg. The inclusion criteria was SBP 160‐219 mmHg and DBP <90 mmHg. Patients were followed for 4.5 years | |

| Interventions | Chlorthalidone 12.5‐25 mg (69%), Step 2. atenolol 25‐50 mg (23%) or reserpine 0.05‐0.1 mg. Identical placebo | |

| Outcomes | Mortality, stroke, CHD, CHF, systolic BP and diastolic BP | |

| Notes | Total CVS verified remains same | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Screenees were randomly allocated by the coordinating center to one of two treatment groups. Randomization was stratified by clinical center and by antihypertensive medication status at initial contact." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinding of patients and investigators was achieved. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients with non‐fatal outcomes were not censored. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified in report. |

VA‐NHLBI.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo controlled. Trial conducted in USA | |

| Participants | Ambulatory patients, with mean age 37.5 years, range (21‐50 years). 25% patients were African‐Americans. Male (100%). Baseline mean DBP was 93.3 mmHg. The inclusion criteria was DBP 85‐105 mmHg. Patients were followed for 2 years. Target < 85 mmHg | |

| Interventions | CHTD 50 mg, 100 mg, (53% CHTD alone). Reserpine 0.25 mg. Control: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Mortality, stroke, CHD, CHF, and diastolic BP | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Use of randomization number and subjects were "randomized in double‐blind fashion into active drug therapy and placebo groups". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Blinding of investigators and patients was achieved. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| COOPE | Only 2 subjects met criteria defined in this review. |

| FEVER 2005 | Not a placebo or no treatment controlled trial. |

| HDFP | No untreated control group. |

| MRC2 | Only 2 subjects met criteria defined in this review. |

| MRFIT | No untreated / placebo control group. |

| Oslo | Approximately half of the subjects had moderately elevated BP and data was not available for the subjects with mild elevation of BP separately. |

| USPHSHC | Approximately half of the subjects had moderately elevated BP and data was not available for the subjects with mild elevation of BP separately. |

Contributions of authors

FG provided the data from the INDANA database for the specific population of interest. JMW, DD, FG were responsible for deciding trials to be included. DD and JMW were responsible for data entry and DD wrote the initial draft. DKC suggested the topic for the review and edited the manuscript. All authors were responsible for interpreting the data and reviewing the final draft.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Department of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology & Therapeutics, University of British Columbia, Canada.

Clinical Pharmacology Department, Hospices Civils de Lyon, France.

UMR5558, CNRS, France.

Claude Bernard University Lyon I, France.

BIMBO project, SYSCOMM 2008 Nr 002, ANR‐ www.agence‐nationale‐recherche.fr, France.

External sources

CIHR Grant to the Hypertension Review Group, Canada.

British Columbia Ministry of Health Grant to the Therapeutics Initiative, Canada.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions), comment added to review

References

References to studies included in this review

ANBP {published data only}

- A report by the Management Committee of the Australian Theraputic Trial in Mild Hypertension. Untreated mild hypertension. Lancet 1982;1(8265):185‐91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abernethy JD. The Australian Therapeutic Trial in Mild Hypertension. Hypertension 1984;6(5):774‐6 1984;6(5):774‐776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abernethy JD. The need to treat mild hypertension. Misinterpretation of results from the Australian trial. JAMA 1986;256(22):3134‐37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Australian Therapeutic Trial in Mild Hypertension. Report by the management committee. Lancet 1980;1:1261‐1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AE. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in mild hypertension: The Australian Trial. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 1985;7(Suppl 2):S10‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AE. The Australian Therapeutic Trial in Mild Hypertension. Nephron 1987;47(Suppl 1):115‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Foundation of Australia. Treatment of mild hypertension in the elderly. Med J Aust 1981;2:398‐402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CA. Australian Therapeutic Trial in Mild Hypertension. [Letter]. Lancet 1980;2(8191):425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reader R. Australian Therapeutic Trial in Mild Hypertension. Medical Journal of Australia 1984;140(13):752‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Report by Management committee of the ATTMH. Initial results of the Australian Therapeutic Trial in mild hypertension (ATTMH). Clinical Science 1979;57:449s‐452s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MRC {published data only}

- Anonymous. Adverse reactions to bendrofluazide and propanolol for the treatment of mild hypertension. Report of Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild to Moderate Hypertension. Lancet 1981;2(8246):539‐43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Coronary heart disease in Medical Research Council trial of mild hypertension. Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild Hypertension. British Heart Journal 1988;59(3):364‐378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Course of blood pressure in mild hypertension after withdrawal of long term antihypertensive treatment. Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild Hypertension. Brit Med J 1986;293(6553):988‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Randomised controlled trial of treatment of mild hypertension: design and pilot trial. Report of the Medical Research Council Working party on mild to Moderate Hypertension. Brit Med J 1977;1(6074):1437‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Stroke and coronary heart disease in mild hypertension: risk factors and the value of treatment. Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild Hypertension. Brit Med J 1988;296(6636):1565‐70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Research council Working Party. MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br Med J 1985;291:97‐104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miall WE. Brennan PJ, Mann AH. Medical research Council's Treatment Trial for mild hypertension: an interim report. Clinical Science and Molecular Medicine 1976;51:563s‐565s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peart S. Results of the MRC (UK) trial of drug therapy for mild hypertension. Clinical and Investigative Medicine 1987;10(6):616‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peart S. Barnes GR. Briughton PMG. Dollery CT, et al. Comparison of the antihypertensive efficacy and adverse reactions to two doses of bendrofluazide and hydrochlorothiazide and the effect of potassium supplementation on the hypotensive action of bendrofluazide: substudies of the Medical Research Council's trials of treatment of hypertension. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1987;27(4):271‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SHEP {published data only}

- Applegate WB. Davis BR. Black HR, et al. Prevalence of postural hypotension at baseline in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP) cohort. Journal of American Geriatric Society 1991;39:1057‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden D. Allman R. McDonald R, et al. Age, race, and gender variation in the utilization of coronary artery bypass surgery and angioplasty in SHEP. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 1994;42:1143‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black HR. Unger D. Burlando A, et al. Part 6: Baseline physical examination findings.. Hypertension 1991;17(3 (Suppl II)):II‐77‐II‐101. 1991;17(Suppl II):77‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borhani NO. Applegate WB. Cutler JA, et al. Part 1: rationale and design. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):2‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain E. Palensky J. Blood J and Wittes J. Blinded subjective rankings as a method of assessing treatment effect: a large sample example from the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP). Statistics in Medicine 1997;16:681‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curb JD. Lee M. Jensen J, Applegate W. Part 4: baseline medical history findings. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):35‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curb JD. Pressel SL. Cutler JA, et al. Effect of diuretic based antihypertensive treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in older diabetic patients with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA 1996;276:1886‐92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BR. Wittes J. Pressel S, et al. Statistical considerations in monitoring the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP). Controlled Clinical Trials 1993;14:350‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franse LV. Pahor M. Di Bari M, et al. Serum uric acid, diuretic treatment and risk of cardiovascular events in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. Journal of Hypertension 2000;18:1149‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost PH. Davis BR. Burlando AJ, et al. Serum lipids and incidence of coronary heart disease. Findings from the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. Circulation 1996;94:2381‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WD. Davis BR. Frost P, et al. Part 7: Baseline laboratory characteristics. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):102‐122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins CM. Isolated systolic hypertension, morbidity and mortality: The SHEP experience. American Journal of Geriatric Cardiology 1993;2(5):25‐27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostis JB. Allen R. Berkson DM, et al. Correlates of ventricular ectopic activity in isolated systolic hypertension. American Heart Journal 1994;127:112‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostis JB. Davis BR. Cutler J, et al. Prevention of heart failure by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA 1997;278(3):212‐216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostis JB. Lacy CR. Hall D, et al. The effect of chlorthalidone on ventricular ectopic activity in patients with isolated systolic hypertension. American Journal of Cardiology 1994;74:464‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostis JB. Prineas R. Curb JD, et al. Part 8: Electrocardiographic characteristics.. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):123‐151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard J. Day M. Chatellier G, Laragh JH. Some lessons from systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP). American Journal of Hypertension 1992;5:325‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB. Tyrrell KS, Kuller LH. Mortality over four years in SHEP participants with a low ankle‐arm index. Journal of American Geriatric Society 1997;45:1472‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry HM. Davis BR. Price TR, et al. Effect of treating isolated systolic hypertension on the risk of developing various types and subtypes of stroke. JAMA 2000;284(4):465‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich H. Byington R. Bailey G, et al. Part 2: screening and recruitment. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):17‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probstfield JL. Applegate WB. Borhani NO, et al. The systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP): an intervention trial on isolated systolic hypertension. Clinc and Exper Hypertension‐Theory and Practice 1989;A11(5 & 6):973‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEP cooperative Research Group. Rationale and design of a randomized clinical trial on prevention of stroke in isolated systolic hypertension. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1988;41(12):1197‐1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEP cooperative research group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the SHEP. ACP Journal Club 1991;115(3):65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEP cooperative research group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 1991;265(24):3255‐64. [PUBMED: 2046107] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage PJ. Pressel SL. Curb D, et al. Influence of long‐term, low‐dose, diuretic‐based, antihypertensive therapy on glucose, lipid, uric acid, and potassium levels in older men and women with isolated systolic hypertension. Archives of Internal Medicine 1998;158:741‐751. 1998;158:741‐751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt TM. Schron E. Pressel S, et al. Part 3: Sociodemographic characteristics. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):24‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassertheil S. Applegate WB. Berge K, et al. Change in depression as a precursor of cardiovascular events. Archives of Internal Medicine 1996;156:553‐561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserthell‐Smoller S. FannC. Allman RM, et al. Relation of low body mass to death and stroke in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. Archives of Internal Medicine 2000;160:494‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler PG. Camel GH. Chiappini M, et al. Part 9: Behavorial characteristics. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):152‐161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittes J. Davis B. Berge K, et al. Part 10: Analysis. Hypertension 1991;17(Suppl II):162‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

VA‐NHLBI {published data only}

- Perry HM Jr, Goldman AI, Lavin MA, Schnaper HW, Fitz AE, et al. Evaluation of drug treatment in mild hypertension: VA‐NHLBI feasibility trial. Plan and preliminary results of a two‐year feasibility trial for a multicenter intervention study to evaluate the benefits versus the disadvantages of treating mild hypertension. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1978;304:267‐92. [PUBMED: 360921] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]