Abstract

Background:

Comparing the course of antipsychotic-naïve psychosis in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) may help to illuminate core pathophysiologies associated with this condition. Previous reviews-primarily from high-income countries (HIC)-identified cognitive deficits in antipsychotic-naïve, first-episode psychosis, but did not examine whether individuals with psychosis with longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP > 5 years) were included, nor whether LMIC were broadly represented.

Method:

A comprehensive search of PUBMED from January 2002-August 2018 identified 36 studies that compared cognitive functioning in antipsychotic-naïve individuals with psychosis (IWP) and healthy controls, 20 from HIC and 16 from LMIC.

Results:

A key gap was identified in that LMIC study samples were primarily shorter DUP (<5 years) and were primarily conducted in urban China. Most studies matched cases and controls for age and gender but only 9 (24%) had sufficient statistical power for cognitive comparisons. Compared with healthy controls, performance of antipsychotic-naïve IWP was significantly worse in 81.3% (230/283) of different tests of cognitive domains assessed (90.1% in LMIC [118/131] and 73.7% [112/152] in HIC).

Conclusions:

Most LMIC studies of cognition in antipsychotic-naïve IWP adopted standardized procedures and, like HIC studies, found broad-based impairments in cognitive functioning. However, these LMIC studies were often underpowered and primarily included samples typical of HIC: primarily male, young-adult, high-school educated IWP, in their first episode of illness with relatively short DUP (<5 years). To enhance understanding of the long-term natural course of cognitive impairments in untreated psychosis, future studies from LMIC should recruit community-dwelling IWP from rural areas where DUP may be longer.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Untreated, Cognition, Low- and middle-income, Countries

1. Introduction

Examining the relationship of untreated psychotic illness to the course of schizophrenia helps to elucidate its natural history and pathophysiology. Longer DUP is associated with poor clinical outcomes (Wyatt and Henter, 1998), more severe positive and negative symptoms, lower rates of remission (e.g. Chang et al., 2013; Penttilä et al., 2014; Cechnicki et al., 2014; Keshavan et al., 2003; Sullivan et al., 2018), greater loss of social function (Aikawa et al., 2018; Chechnicki, et al., 2014), and hippocampal atrophy (Goff et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2014; Rund, 2014). Studies of untreated psychotic illnesses from high-income countries (HIC; using classifications from the World Bank, The World Bank Group, n.d) typically identify individuals with relatively short DUP-usually under 2 years and rarely over 5 years (Torrey, 2002; Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014). Conversely, untreated individuals with psychosis (IWP) living in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) often have much longer DUP, primarily due to limited access to scarce treatment resources (e.g. McCreadie et al., 2002; Mossaheb et al., 2013; Thirthalli et al., 2011). Assessment of cognitive function in untreated IWP with longer DUP would provide invaluable information on the natural course of psychotic illness and could inform the appropriate management of the many IWP in LMIC who remained untreated for years. As a first step in advancing this area, this systematic review compares the results and methodological rigor of studies of cognition in untreated IWP in HIC and LMIC.

1.1. Knowledge gained by examining antipsychotic-naïve psychosis in long-term DUP

Examining the clinical, cognitive and neurophysiological characteristics of IWP with varying DUP illuminates the natural course of psychotic illness unbiased by the effects of antipsychotic medication. The natural trajectory of cognitive decline in schizophrenia is unclear regarding whether there is stabilization after the initial episode of illness, progressive decline, or gradual improvement. Moreover, the effects of treatment at whatever point of intervention are unknown. Clarifying this issue may help illuminate causal pathways for the changes in functional capacity and neuropathology seen in chronic psychosis.

1.2. Cognitive deficits in treated and untreated first-episode IWP: corroboration in LMIC

For both treated and untreated first-episode schizophrenia, cognitive dysfunction is robust, well-established, and presents as both broad cognitive impairments and as more specific impairments in attention, memory, language, motor and executive functioning (e.g. Blanchard and Neale, 1994; Bora et al., 2009; Dickinson et al., 2004; Gold and Harvey, 1993, Green, 1996; Nuechterlein et al., 2004; Schaefer et al., 2013; Stone and Seidman, 2016). Medium-to-large impairments in cognition were reported in Mesholam-Gately and colleagues' meta-analysis of 47 first-episode studies of IWP, 92% (43/47) of which were conducted in HIC, 96% (45/47) in urban locales, and 64% (30/47) with samples who had already initiated medication at time of assessment. The relatively prompt initiation of antipsychotic medication following onset of psychosis in HIC (typically within 2 years) may prevent subsequent deterioration in cognitive functioning in individuals with chronic schizophrenia who remain on antipsychotic medications (Heinrichs and Zakzanis, 1998).

Given that prior antipsychotic medication use may obscure observed cognitive impairments, other studies have assessed cognitive functioning in first-episode, antipsychotic-naïve samples (i.e., individuals who had never received any antipsychotic medications). A first, nonsystematic review of 65 cross-sectional studies by Torrey (2002) identified five studies, all showing poorer cognitive functioning among first-episode, antipsychotic-naïve individuals with schizophrenia compared with healthy controls. Across these five identified studies, one study reported generalized cognitive impairments, and the remaining four studies reported that untreated IWP showed deficits in the domains of verbal memory and learning, attention, spatial memory, language, and attention. All five studies were conducted in urban settings, four of the five studies were conducted in HIC, and mean DUP was relatively short in the 4 HIC studies (2.0–3.3 years). A subsequent meta-analysis of 23 cross-sectional studies (Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014) reported medium-to-large cognitive impairments among antipsychotic-naïve, first-episode IWP compared with healthy controls; all 23 studies were conducted in urban settings, 70% (16/23) were conducted in HIC (with all but one of the seven LMIC studies conducted in urban China), and range in mean DUP in the 16 HIC studies was relatively short (4.9 months-4.6 years). Other meta-analyses of antipsychotic-naïve, first-episode psychosis– primarily limited to HIC studies with relatively shorter DUP –reported no clear relationship between DUP and severity of neuropsychological impairment (Allott et al., 2018; Bora et al., 2018).

In sum, cognitive impairments have been corroborated in cross-sectional, first-episode, antipsychotic-naïve samples with relatively short DUP, nearly all of which are identified in urban settings, and most of which come from HIC. However, it remains unknown whether cognitive impairments identified in these untreated first-episode IWP from urban settings with better access to psychiatric services will be similar to those in rural locales of LMIC, where mental health services are scarce (or non-existent) and many IWP remain untreated for longer periods (well-beyond the first episode of illness). Specifically, it remains unknown whether the natural trajectory of cognitive function in untreated psychosis is stabilization after a first psychotic episode, continued decline as DUP increases or a divergence of cognitive trajectories depending on individual characteristics. Hence, an important step would be to assess to what extent cognition studies in LMIC assess first episode IWP with longer DUP, and to what extent these include a broad representation of LMIC and rural locales, given that prior reviews have identified that LMIC studies have been primarily conducted in urban China (Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014).

1.3. Evaluating study methodology and examining longitudinal comparisons of antipsychotic-naïve IWP

This review will also assess the methodological rigor of identified studies in HIC and LMIC using previously-articulated standards (Harvey and Keefe, 2001), focusing on implementation of matching procedures (e.g., age, gender, and socioeconomic status [SES]) which contribute to heterogeneity in cognitive performance (Mesholam-Gately et al., 2009). We further consider the extent to which current study designs are appropriate to investigate longer-term DUP in rural LMIC.

Moreover, to expand on previous reviews of cross-sectional comparisons of antipsychotic-naïve IWP with healthy controls (e.g. Torrey, 2002; Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014), we searched for studies that: 1) examined before versus after changes in cognitive functioning in untreated IWP following initial treatment with antipsychotic medication, and 2) studies that followed trajectory of cognitive functioning in untreated IWP who remained untreated over time.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

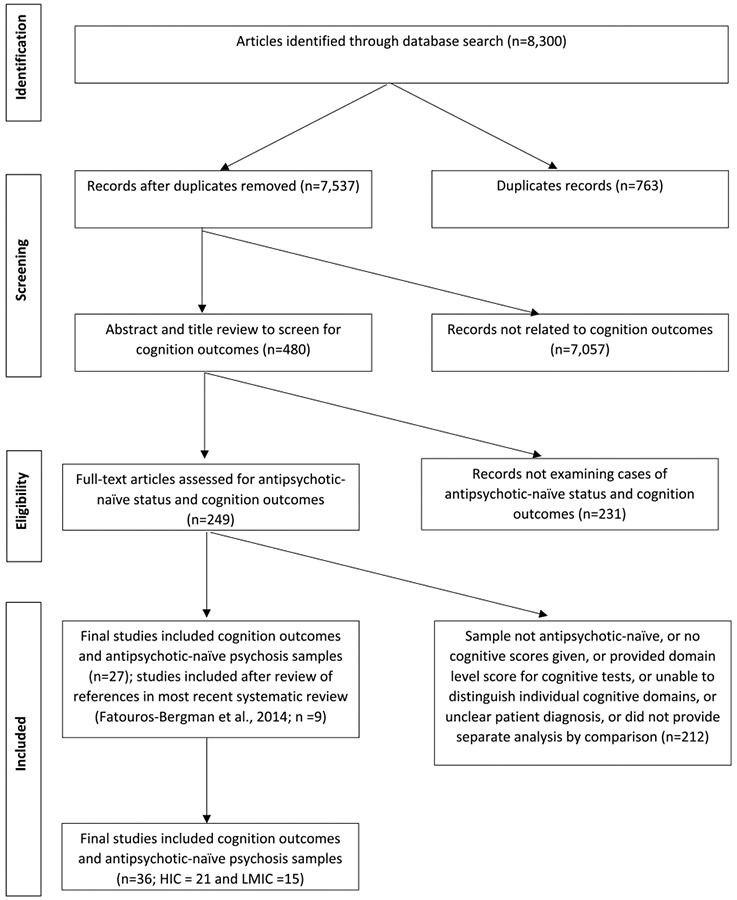

Following a review of studies of cognition functioning of antipsychotic-naïve psychosis up to 2002 (Torrey, 2002), we conducted a systematic literature search via PUBMED using PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) for studies between January 2002–August 2018. We identified additional studies by reviewing the reference list of recent meta-analyses (e.g., Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014). We employed various keywords to capture studies of antipsychotic-naïve IWP, including “untreated”, “first episode”, or “neuroleptic-naïve”; and words including “schizo*”, “psycho*”, “bipolar”, or “delusional” for psychosis (see Supplemental Table A for search terms). To identify HIC and LMIC countries, we conducted an unrestricted search and classified country of study via World Bank economic classifications (The World Bank Group, n.d). After removing duplicates, this strategy yielded 7537 articles (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Systematic literature search for studies comparing antipsychotic naïve IWP vs. healthy controls on cognition outcomes.

2.2. Study selection

Studies were included if they (1) examined cognition; (2) specifically identified IWP as never having taken antipsychotic medications prior to cognition assessment (i.e., had not received any lifetime anti-psychotic treatment, or were explicitly identified as “antipsychotic-naïve”, “drug-naïve” or “neuroleptic naïve”), (3) utilized published cognitive tests, and (4) provided distinct cognition data for the antipsychotic-naïve group. Studies indicating prior antidepressant use were included; those indicating prior anti-anxiolytic (e.g. benzodiazepines) use were excluded given their adverse cognitive effects (Vermeeren and Coenen, 2011). To examine specific cognitive domains, cognitive findings were organized via MATRICS Cognitive Consensus Battery (MCCB) domains (Nuechterlein et al., 2008), including: (1) Speed of processing, (2) Attention/vigilance, (3) Working memory, (4) Verbal learning and memory (5) Visual learning and memory (6) Reasoning and problem solving, and (7) Social cognition.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) included participants with previous exposure to antipsychotic treatment, including medication “washout” periods. Studies where subsamples received antipsychotic medications prior to cognitive assessment were excluded unless distinct data was presented for the antipsychotic-naïve subgroup, (2) solely reported a composite cognition score (i.e., did not report individual tests, because we wished to assess deficits across cognition domains), or (3) were a review/meta-analysis. For article extraction, eight raters examined the first 500 articles, with disagreements resolved via consensus. Subsequently, 4 teams of 2 raters each reviewed the remaining 7537 abstracts and titles for inclusion, with disagreements resolved via discussion with the first (L.Y.) or senior authors (L.S. or W.S.). Screening abstracts and titles for cognition outcomes yielded 480 relevant articles (Fig. 1); full-text was then examined for distinct samples of antipsychotic-naïve IWP, yielding 249 studies. Finally, report of independent cognition domains was confirmed, resulting in 27 studies. Only 6 of our identified studies (Chan et al., 2006; Andersen et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2007; Krieger et al., 2005; Nejad et al., 2011; Van Veelen et al., 2011) overlapped with the Fatouros-Bergman et al. (2014) meta-analysis. Examining the Fatouros-Bergman et al. (2014) meta-analysis yielded nine new studies (likely because our review required direct language signifying “antipsychotic-naïve” status; Brickman et al., 2004; Fagerlund et al., 2004; He et al., 2013; Hill et al., 2004a; Hill et al., 2004b; Hilti et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2012; Salgado-Pineda et al., 2003), resulting in 36 studies examining antipsychotic-naïve IWP vs. healthy controls.

2.3. Data extraction

We primarily examined antipsychotic-naïve IWP compared with healthy controls (n = 36 studies). Additionally, our systematic search identified two studies examining a longitudinal, pre- versus post-antipsychotic medication treatment design; i.e., when antipsychotic-naïve individuals at baseline received antipsychotic medications, with cognition assessed at two time-points (one of which was identified in the n = 36 studies prior). No longitudinal cognition studies were identified with antipsychotic-naïve IWP who remained untreated with antipsychotics.

To characterize study samples, we extracted (Tables 1A and 1B): (1) Sociodemographic and study variables including: a) sample size; b) age; c) gender; d) education; e) parental socioeconomic status; f) country; g) urban vs. rural; h) HIC vs. LMIC; (2) Clinical variables including: a) psychosis diagnosis, b) diagnostic criteria; c) DUP, or the interval between onset of psychotic disorder and receipt of first antipsychotic medication treatment (or alternatively, Duration of Untreated Illness, if DUP was unavailable); d) non-antipsychotic medication use (if present), and f) recruitment setting (e.g. outpatient vs. inpatient). Due to limited reporting, race/ethnicity was not included. Among studies comparing antipsychotic-naïve IWP with healthy controls, we subgrouped results by LMIC (gross national income [GNI] per capita, as defined by the Atlas conversion factor [The World Bank, 2019], between $1026–$12,375) vs. HIC (GNI per capita ≥$12,376; The World Bank Group, n.d). Since all studies (but one) were conducted in urban areas, subgrouping by urban/rural locale was not conducted. (See Tables 1A.)

Table 1A.

Demographic characteristics of study samples.

| Study | Sample Size |

Age; Mean (SD) | Gender | Years of Education | Parental SES | Country of Study |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| APN IWP |

HC | APN IWP | HC | APN IWP (% Male) |

HC (%Male) |

APN IWP | HC | APN IWP | HC | ||

| HIC | |||||||||||

| Arnado and Olié (2006)(study 2) | 12 | 12 | 27 (6.9) | 24.6 (3.5) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | France |

| Andersen et al. (2013) | 48 | 48 | 25.4 (5.3) | 26.6 (5.4) | 35 (73) | 35 (73) | 12.1 (2.7) | 14.8 (2.2) | High = 24 Middle = 20 Low = 3 |

High = 32 Middle = 14 Low = 2 |

Denmark |

| Anhøj et al. (2018) | 47 | 47 | 24.6 | 24.7 | 29 (61.7) | 29 (61.7) | 12.1(2.6) | 14(2.7) | NR | NR | Denmark |

| Anilkumar et al. (2008) | 13 | 13 | 26.1 (9.5) | 28.2 (9.8) | 7 (53.8) | 7 (53.8) | NR | NR | NR | NR | UK |

| Boksman et al. (2005) | 10 | 10 | 22.0 (5.0) | 23.0 (4.0) | 9 (90) | 9 (90) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Canada |

| Brickman et al. (2004) | 29 | 17 | 16.1 (2.0) | 16.9 (2.4) | 15 (51.7) | 9 (52.9) | NR | NR | 3.7 (1.1)a | 2.5 (0.7)a | USA |

| Chan et al. (2006) | 78 | 60 | 28.5 (9.8) | 27.9 (9.1) | 49 (62.8) | 19 (31.7) | 10.8 (2.5) | 10.4 (2.1) | NR | NR | Hong Kong (China) |

| Chan et al. (2014) | 71 | N/A | 26.6 (11.2) | N/A | 39 (54.9) | N/A | 11.2 (2.9) | N/A | NR | N/A | Hong Kong (China) |

| Fagerlund et al. (2004) | 25 | 25 | 27.3 (5.9) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | High SES = 3 Middle SES = 18 Low SES = 4 |

High SES =9 Middle SES =16 |

Denmark |

| Forest et al. (2007) | 8 | 8 | 31.0 (19.9) | 21.4 (4.9) | 6 (75) | 6 (75) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Canada |

| Harris et al. (2009) | 25 | 22 | 25.4 (7.6) | 23.1 (4.2) | 18 (72) | 14 (63.6) | NR | NR | NR | NR | USA |

| Hill et al. (2004a, 2004b) | 86 | 81 | 28.5 (9.6) | 29.8 (10.6) | 53 (61.6) | 45 (55.6) | 13.4 (3.0) | 14.5 (2.1) | 2.9 (1.2)b | 2.8 (1.1)b | USA |

| Hill et al. (2004a, 2004b) | 62 | 67 | 26.3 (8.9) | 28 (9.9) | 36 (58.1) | 36 (55.2) | 13.3(2.9) | 14.3(1.8) | 3.0(1.2)c | 2.7(1.0)c | USA |

| Hilti et al. (2010) | 29 | 33 | 22.0 (4.0) | 23.2 (2.8) | 24 (82.8) | 24 (72.7) | 9.5 (1.3) | 12.7 (1.5) | NR | NR | Switzerland |

| Krieger et al. (2005) | 12 | 12 | 24.6 (5.8) | 25.8 (6.2) | 6 (50) | 6 (50) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Germany |

| Kruiper et al. (2019) | 73 | 93 | 25.4 (5.7) | 25.6 (5.7) | 50 (68.5) | 62 (66.7) | 12.2 (2.4) | 14.8 (2.7) | High =21 Medium =39 Low =8 |

High =36 Medium =43 Low =11 |

Denmark |

| Levitt et al. (2002) | 15 | 14 | 38.5 (11.0) | 38.0 (10.5) | 15 (100) | 14 (100) | 15.2 (3.2) | 14.9 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.1) | USA |

| Nejad et al. (2011) | 23 | 35 | 26.2 (5.0) | 26.8 (5.8) | 18 (78.3) | 24 (68.6) | NR | NR | High = 10 Middle = 10 Low = 3 |

High = 28 Middle = 6 Low = 1 |

Denmark |

| Salgado-Pineda et al. (2003) | 13 | 13 | 23.8 (5.7) | 23.4 (4.6) | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Spain |

| Schérer et al. (2003) | 11 | 11 | 29.0 (3.7) | 27.0 (7.2) | 8 (72.7) | 9 (81.8) | 12.6 (3.0) | 12.0 (3.3) | NR | NR | Canada |

| Van Veelen et al. (2011) d | 23 | 33 | 25.3 (4.6) | 24.5 (4.7) | 23 (100) | 33 (100) | 11.2 (2.7) | 13.2 (2.4) | NRa | NRa | Netherlands |

| LMIC | |||||||||||

| Chen et al. (2014) | 49 | 57 | 26.7 (7.0) | 29.0 (8.0) | 29 (59.2) | 24 (42.1) | 14.4 (2.8) | 14.1(2.7) | NR | N/A | China |

| Emsley et al. (2015) | 22 | 23 | 24.6 (6.1) | 27.8 (8.9) | 19 (86) | 15 (65) | 19 (86.4% Secondary) 3 (13.6% Tertiary) |

1 (4% Elementary) 20 (87% Secondary) 2 (9% Tertiary) |

NR | NR | South Africa |

| Guo et al. (2014) | 51 | 41 | 22.5 (4.1) | 22.8 (3.9) | 33 (64.7) | 24 (58.5) | 11.4 (3.3) | 11.9 (2.7) | NR | NR | China |

| He et al. (2013) | 115 | 113 | 25.4(8.3) | 26.6(8.9) | 53 (46.1) | 57 (50.4) | 12.1(3.1) | 12.7(3.5) | NR | NR | China |

| Hu et al. (2011) | 56 | 56 | 21.2 (3.4) | 21.9 (2.9) | 37 (66.1) | 37 (66.1) | NR | NR | NR | N/A | China |

| Huang et al. (2016) | 92 | 57 | 22.9 (7.8) | 23.8 (8.7) | 36 (39.1) | 24 (42.1) | 10.8 (3.0) | 11.8 (3.4) | NR | NR | China |

| Huang et al. (2017) | 58 | 43 | 22.7 (7.6) | 23.1 (7.5) | 29 (50.0) | 16 (37.2) | 11.4 (2.7) | 12.7 (3.8) | NR | NR | China |

| Liu et al. (2018) | 48 | 31 | 15.8(1.6) | 15.4(1.5) | 21 (43.7) | 14 (45.2) | 8.9 (2.0) | 8.4 (1.6) | NR | NR | China |

| Lu et al. (2012) | 112 | 63 | 25.2 (4.3) | 26.1 (3.7) | 59 (52.7) | 35 (55.6) | 12.5 (3.6) | 14.8 (2.5) | NR | NR | China |

| Man et al. (2018) | 80 | 80 | 25.7(8.9) | 34.9(8.8) | 43 (53.8) | 46 (57.5) | 8.5(3.0) | 9.5(3.1) | NR | NR | China |

| Wang et al. (2007) | 112 | 452 | 22.6 (7.7) | 34.0 (11.7) | 60 (53.6) | 221 (48.9) | 11.9 (4.6) | 10.3 (3.7) | NR | NR | China |

| Wu et al. (2016) | 79 | 124 | 25.7 (7.8) | 44.7 (8.8) | 43 (54.4) | 65 (52.4) | 12.7 (3.2) | 11.8 (3.4) | NR | NR | China |

| Xiao et al. (2017) | 58 | 55 | 25.0(5.9) | 26.5(6.6) | 31(53.4) | 33 (60.0) | 10.2(3.1) | 11.3(3.2) | NR | NR | China |

| Xiu et al. (2016) | 256 | 540 | 26.4 (9.1) | 27 (11.8) | 150 (58.6) | 300 (55.6) | 9.5 (3.7) | 9.1 (3.9) | NR | NR | China |

| Zhang et al. (2013) | 244 | 256 | Smoker = 29.8 (9.3); Non--smoker = 25.7 (9.2) |

Smoker = 29.1 (7.3); Non--smoker = 25.9 (8.6) |

164 (67.2) | 176 (68.8) | Smoker = 11.1 (3.8) Non-smoker = 11.7 (4.1) |

Smoker = 11.5 (3.9) Non-smoker = 12.4 (3.4) |

NR | NR | China |

| Zhang et al. (2015) | 26 | 28 | 23.0 (6.9) | 26.5 (8.2) | 20 (76.9) | 15 (53.6) | 11.5 (2.6) | 13.5 (3.3) | NR | NR | China |

APN = Antipsychotic-Naive

HC = Healthy Control

IWP = Individual With Psychosis

NR = not reported

Parental SES determined with 5 point-scale from CASH.

Parental SES measured on Hollingshead Index of Social Position.

Unable to ascertain measure of SES.

Only study conducted in a rural setting.

Table 1B.

Clinical characteristics of study samplesb.

| Study | Diagnosis of AP naïve IWP | Diagnostic criteria | DUP/DUI/Age of Onset weeks+/−SD (years +/−SD) |

Non-antipsychotic medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnado and Olié (2006) (study 2) | Schizophrenia | NR | DUIa = 208.6 +/− 104.3 (4 ±2) | NR |

| Andersen et al. (2013) | Schizophrenia: Paranoid = 36 (75%), Hebephrenic = 3 (6%), Undifferentiated = 5 (11%), & Unspecified = 2 (4%); Schizoaffective disorder = 2 (4%) | SCAN for ICD-10 & DSM-IV | DUI = 790.8 ±960.3 (15.2+/− 18.4) | Benzodiazepines = 21 (43.8%) |

| Anhøj et al. (2018) | Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | ICD-10 | DUI = 59 +/− 69 (1.1 +/− 1.3) | NR |

| Anilkumar et al. (2008) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUI = <8.7 weeks | NR |

| Boksman et al. (2005) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUIa = 73.9±43.5 (1.4±0.83) | One patient had received 20 mg of citalopram for 2 months that was stopped 2 weeks before the assessment. Another patient received 0.5 mg lorazepam within the 24 h before the assessment. |

| Brickman et al. (2004) | Schizophrenia = 18 (62%), Schizoaffective disorder = 4 (13.8%), Bipolar disorder = 5 (17.2%), Major depression with psychosism = 1 (3.5%), Psychotic disorder NOS = 1 (3.5%) | Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History for DSM-IV | NR | NR |

| Chan et al. (2006) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUP = 35.5 ±63.1 (0.7±1.2) | NR |

| Chan et al. (2014) | Schizophrenia = 47 (66.2%), Schizoaffective disorder = 15 (21.1%), Schizophreniform disorder = 5 (7.0%), & Brief psychotic disorder = 4 (5.6%) | DSM-IV (did not report clinical interview) | DUP median = 35 (0.7) | NR |

| Fagerlund et al. (2004) | Schizophrenia | SCAN for ICD-10 | DUP = 17.4–338.9, median 60.8 (0.3–6.5, median 1.2) | NR |

| Forest et al. (2007) | Schizophrenia | DSM-IV-R (did not report clinical interview) | NR | NR |

| Harris et al. (2009) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | NR | At 6 week follow up (post-antipsychotic evaluation): 4 received antidepressant medication, 1 received lithium |

| Hill et al. (2004a, 2004b) | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder (schizophrenia [N = 71 (82.6%)] or schizoaffective disorder [N = 15] (17.4%)) | SCID for DSM- III-R or DSM-IV | NR | 21 were on antidepressants prior to assessment (Mean = 6 weeks) |

| Hill et al. (2004a, 2004b) | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder | SCID for DSM-IV | NR | NR |

| Hilti et al. (2010) | Schizophrenic, Schizophreniform, or Schizoaffective disorder | ICD-10 and DSM-IV | NR | NR |

| Krieger et al. (2005) | Schizophrenia or Schizophreniform Disorder | DSM-IV (did not report clinical interview) | NR | NR |

| Kruiper et al. (2019) | Schizophrenia | SCAN for ICD-10 & DSM-IV | NR | NR |

| Levitt et al. (2002) | Schizotypal Personality Disorder & paranoid personality disorders, borderline personality disorders, depression, dysthymia, panic disorder, alcohol abuse, and polysubstance abuse | SCID-P & SCID-II for DSM-IV | NR | no current use of psychotropic medications |

| Nejad et al. (2011) | Schizophrenia | SCAN for DSM-IV | NR | Benzodiazepines = 8, Fluoxetine = 1, & Citalopram =1 |

| Salgado-Pineda et al. (2003) | Schizophrenia (all paranoid subtype) | SCID for DSM-IV | NR | NR |

| Schérer et al. (2003) | Schizophrenia | DSM-IV (did not report clinical interview) | NR | NR |

| van Veelen et al. (2011) | Schizophrenia = 12 (52.2%) & Schizophreniform disorder = 11 (47.8%) | SCID for DSM-IV or CASH | DUI = 21.3±18.7 (0.4±0.4) | Benzodiazepines = 2 (8.7%) |

| LMIC | ||||

| Chen et al. (2014) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUI = 55.3±75.6 (1.06±1.45) DUP = | None |

| Emsley et al. (2015) | 9 (41% Schizophreniform disorder) & 12 (59% Schizophrenia) | SCID for DSM-IV | 40.7±40.3 (0.8±0.7) | NR |

| Guo et al. (2014) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUI = 36.5±29.5 (0.7±0.6) | NR |

| He et al. (2013) | Schizophrenia = 94 (81.7%), Schizophreniform psychosis = 21 (18.3%) patients | SCIDfor DSM-IV | DUI = 55.3±78.2 (1.06 ±1.5) | NR |

| Hu et al. (2011) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUI = 44.2±29.4 (0.8±0.6) | None |

| Huang et al. (2016) | schizophrenia | DSM-IV | DUI = 53.3±79.8 (1.1±1.5) | NR |

| Huang et al. (2017) | first episode schizophrenia | ICD-10 and MINI | DUIa: 65.8±108.7 (1.3±2.1) DUI: | NR |

| Liu et al. (2018) | first episode schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | 23.2±26.6 (0.5±0.5) | NR |

| Lu et al. (2012) | first episode schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | NR | NR |

| Man et al. (2018) | Schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUI <260.7(< 5) | None |

| Wang et al. (2007) | first episode schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | DUI = 57.4±71.6 (1.1±1.4) | NR |

| Wu et al. (2016) | first episode schizophrenia | DSM-IV | 1.1+/− 11.03 DUP= | NR |

| Xiao et al. (2017) | first episode schizophrenia | DSM | 26.5±15.6 (0.5±0.3) | None |

| Xiu et al. (2016) | first episode schizophrenia | Chinese version of SCID for DSM-IV | 1.3 +/− 12.7 | None |

| Zhang et al. (2013) | first episode schizophrenia | Chinese version of SCID for DSM-IV | NR | NR |

| Zhang et al. (2015) | first episode schizophrenia | SCID for DSM-IV | First Episode of Psychosis in the past year | NR |

NR = Not Reported.

DUI, calculated by average patient age minus average age of onset of mental illness.

All studies recruited from outpatient or inpatient setting.

To evaluate methodological rigor, we examined implementation of matching procedures among comparisons with healthy control groups only. We noted trends in whether studies accounted for variables of age, gender, and/or parental socioeconomic status via: a) matching, using individual-matching, or group-matching, prior to enrollment or; b) used statistical controls following data collection. We noted the proportion of studies that did not report either matching procedures or statistical controls (See Table 2; “Implementation of Matching Criteria by Studies of Antipsychotic-Naïve Individuals with Psychosis Vs. Healthy Controls”). Results were subgrouped by HIC vs. LMIC. Furthermore, due to consistent cognitive impairments shown in antipsychotic-naïve IWP compared with healthy controls (Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014), we organized studies into subgroups that reported: a) significant impairments for all cognition outcomes for antipsychotic-naïve IWP vs. healthy controls; b) mixed differences (i.e., some significant and some nonsignificant) in cognition outcomes; and c) nonsignificant differences for all cognition outcomes (final column, Table 2). We observed whether matching procedures were applied differently between groups a), b) and c).

Table 2.

Implementation of matching criteria by studies of antipsychotic-naïve individuals with psychosis vs. healthy controls.

HIC = High Income Countries

LMIC = Low- and Middle-Income Countries

SES = Socio-economic Status

- not applicable

significant differences reported by age, gender, or parental SES

✓ matched to the extent possible

unclear = matching unclear, states patient ‘similar by’ gender, age, or parental SES.

1 = IWP worse cognitive function vs Healthy Controls.

2 = some comparisons show IWP worse cognitive function vs. Healthy Controls; and some comparisons show no significant differences between groups.

3 = No comparisons show IWP worse cognitive function vs. Healthy Controls (all findings nonsignificant).

To further evaluate methodological rigor, we examined application of methodological criteria (Table 3-“Implementation of Methodological Criteria by Studies of Antipsychotic-Naïve Individuals with Psychosis vs. Healthy Controls”). While no agreed-upon standard of quality for cognitive studies exists, we assessed implementation of methodological criteria previously used to evaluate studies examining antipsychotic medication effects upon cognition in schizophrenia (Keefe et al., 1999; Harvey and Keefe 2001). For these studies, we evaluated 5 criteria: a) diagnostic tools (e.g. SCID), b) whether sample size was sufficient (n ≥ 64 per group) to detect a medium effect size, the largest cognitive deficit effect size reported by meta-analyses (Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014), c) whether clinical symptoms (i.e. positive, negative, and disorganized) were assessed, which could influence cognitive changes (Mesholam-Gately et al., 2009); d) whether diagnosis of untreated IWP were reported; and e) whether absence of psychosis among healthy controls was verified by structured clinical interview (Table 3). For study quality, we counted how many criteria were met by each study (range 0–5). We organized studies by HIC vs. LMIC, noting any trends for methodology used. We further organized studies into three subgroups that reported differences in cognitive outcomes (final column, Table 3), and observed whether application of methodological criteria differed between subgroups. Finally, because we only identified two pre- vs. post antipsychotic medication treatment studies who were antipsychotic-naïve at baseline (both of which were conducted in HIC), we briefly summarized these study results below.

Table 3.

Implementation of methodological criteria by studies of antipsychotic-naïve individuals with psychosis vs. healthy controls.

| Authors | Diagnostic Interview of APN IWP |

Sufficient sample size |

Assessment

of Clinical Variables |

Diagnosis of APN IWP | Healthy Control Screening Procedure | Criteria Met |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIC | |||||||

| Arnado and Olié (2006) (Study 2) | NR | Untreated (n = 12) Healthy (n = 12) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | NR | 2 | 1 |

| Andersen et al. (2013) | SCAN | Untreated (n = 48) Healthy (n = 48) |

Yes | Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective | Non-standardized screener for psychiatric, neurological, and/or substance use disorder or intellectual disability among: 1) participant; 2) familya | 3 | 1 |

| Boksman et al. (2005) | SCID | Untreated (n = 10) Healthy (n = 10) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | SCID | 4 | 1 |

| Brickman et al. (2004) | CASH | Untreated (n = 29) Healthy (n = 17) |

Yes | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression with psychosis, and psychotic disorder NOS | CASH | 4 | 1 |

| Hill et al. (2004a, 2004b) | SCID | Untreated (n = 86) Healthy (n = 81) |

Yes | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Schizophrenia & schizoaffective disorder) | SCID | 5 | 1 |

| Krieger et al. (2005) | NR | Untreated (n = 12) Healthy (n = 12) |

Yes | First-onset Schizophrenia or Schizophreniform disorder | NR | 3 | 1 |

| Kruiper et al. (2019) | SCAN | Untreated (n = 73) Healthy (n = 93) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | SCAN | 5 | 1 |

| Schérer et al. (2003) | Clinician rating | Untreated (n = 11) Healthy (n = 11) |

Yes | First-Episode Schizophrenia | Non-standardized screener for psychiatric, neurological, and/or substance use disorder among: 1) participant | 2 | 1 |

| van Veelen et al. (2011) | SCID; DSM-IV | n = 35 | Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | MINI | 4 | 1 |

| Anilkumar et al. (2008) | SCID | Untreated (n = 13) Healthy (n = 13) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | SCID | 4 | 2 |

| Anhøj et al. (2018) | SCAN | Untreated (n = 47) Healthy Controls (n = 47) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder | SCAN | 4 | 2 |

| Chan et al. (2006) | SCID | Untreated (n = 78) Healthy (n = 60) |

Yes | First-Onset Schizophrenia | Non-standardized screener for psychiatric and/or neurological disorders & special school attendance among: 1) participant; 2) family | 3 | 2 |

| Fagerlund et al. (2004) | SCAN 2.1 | Untreated (n = 25) Healthy (n = 25) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | SCAN 2.0 | 4 | 2 |

| Harris et al. (2009) | SCID | Untreated (n = 25) Healthy (n = 22) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | SCID | 4 | 2 |

| Hill et al. (2004a, 2004b) | SCID; DSM-IV | Untreated (n = 62) Healthy (n = 67) |

Yes | Schizophrenia & Schizoaffective disorder | SCID | 4 | 2 |

| Hilti et al. (2010) | DIA-X | Untreated (n = 29) Healthy (n = 33) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | DIA-X | 4 | 2 |

| Salgado-Pineda et al. (2003) | BPRS, SAPS, & SANS | Untreated (n = 13) Healthy (n = 13) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | NR | 3 | 2 |

| Forest et al. (2007) | DSM-IV-R criteria by psychiatrist | Untreated (n = 8) Healthy (n = 8) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | Non-standardized screener for psychiatric, neurological, and/or medical disorder among: 1) participant; 2) family | 3 | 3 |

| Levitt et al. (2002) | SCID-P & SCID-II | Untreated (n = 15) Healthy (n = 14) |

Yes | Schizotypal Personality disorder | SCID-P & SCID-II | 4 | 3 |

| Nejad et al. (2011) | SCAN 2.1 | Untreated (n = 20) Healthy (n = 8) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | SCAN-Interview | 4 | 3 |

| Summary (HIC) | |||||||

| Structured: 17 | No: 18 | No: 0 | No: 1 | Structured: 13 | 3.85 (0.81) | ||

| Unstructured: 1 | Yes: 2 | Yes: 20 | Yes: 20 | Unstructured: 4 | |||

| NR: 2 | NR: 3 | ||||||

| LMIC | |||||||

| Chen et al. (2014) | SCID, DSM-IV | Untreated (n = 57) Healthy (n = 49) |

Yes | First episode drug nai’ve schizophrenia | Non-standardized screener for psychiatric disorders among: 1) participant; 2) family | 3 | 1 |

| Guo et al. (2014) | SCID | Untreated (n = 51) Healthy (n = 41) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | Non-standardized screener for medical and/or neurological disorders among: 1) participant; 2) family | 3 | 1 |

| Man et al. (2018) | SCID; DSM-IV | Untreated (n = 80) Healthy (n = 80) |

Yes | Acute schizophrenia | Non-standardized screener for current mental status, psychiatric disorder among: 1) participant; 2) family | 4 | 2 |

| Wang et al. (2007) | SCID; DSM-IV | Untreated (n = 112) Healthy (n = 452) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | SCID-NP | 5 | 1 |

| Wu et al. (2016) | SCID | Untreated (n = 79) Healthy (n = 124) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | Non-standardized Screener: psychiatric disorders among: 1) family | 4 | 1 |

| Xiu et al. (2016) | SCID | Untreated (n = 256) Healthy (540) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | Non-standardized Screener: psychiatric disorders, past mental status among: 1) participant; 2) family | 4 | 1 |

| Zhang et al. (2013) | SCID | Untreated (n = 244) Healthy (256) |

Yes | Schizophrenia | Non-standardized Screener: Psychiatric disorders among 1) participant; 2) family | 4 | 1 |

| Zhang et al. (2015) | SCID | Untreated (n = 26) Healthy (n = 28) |

Yes | First-Episode Schizophrenia | Non-standardized Screener: psychiatric disorders among: 1) family | 3 | 1 |

| Hu et al. (2011) | SCID; DSM-IV | Untreated (n = 56) Healthy (n = 56) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | SCID-IV | 4 | 1 |

| He et al. (2013) | SCID-P; DSM-IV | Untreated (n = 115) Healthy (n = 113) |

Yes | Schizophrenia & Schizophreniform | SCID-NP | 5 | 1 |

| Lu et al. (2012) | NR | Untreated (n = 112) Healthy (n = 394) |

Yes | First Episode Schizophrenia | Non-standardized Screener: Psychiatric disorder among 1) participant; 2) family | 3 | 1 |

| Liu et al. (2018) | SCID | Untreated (n = 48) Healthy (n = 31) |

Yes | First-episode schizophrenia | SCID | 4 | 1 |

| Huang et al. (2017) | MINI, ICD-10 F20 | Untreated (n = 58) Healthy (n = 43) |

Yes | First-episode neuroleptic-naive schizophrenia patients | MINI, ICD-10 | 4 | 1 |

| Emsley et al. (2015) | SCID | Untreated (n = 22) Healthy (n = 23) |

Yes | Schizophreniform disorder or Schizophrenia | SCID | 4 | 2 |

| Huang et al. (2016) | SCID; DSM-IV-TR | Untreated (n = 92) Healthy (n = 57) |

Yes | First-episode schizophrenia | Non-standardized Screener: Psychiatric, medical and/or neurological disorder, intellectual disability and/or MRI evidence of structural brain abnormalities among: 1) family . | 3 | 2 |

| Xiao et al. (2017) | NR; DSM-5 criteria for schizophrenia | Untreated (n = 58) Healthy (n = 55) |

Yes | First episode schizophrenia | Non-standardized Screener: Psychiatric and/or medical disorder among: 1) participant 2) family. | 2 | 2 |

| Summary (LMIC) | |||||||

| Structured: 14 | No: 9 | No: 0 | No: 0 | Structured: 6 | 3.69 (0.79) | ||

| Unstructured: 1 | Yes: 7 | Yes: 16 | Yes: 16 | Unstructured: 10 | |||

| NR: 1 | NR: 0 |

1 = IWP worse cognitive function vs Healthy Controls.

2 = some comparisons show IWP worse cognitive function vs. Healthy Controls.

3 = No comparisons show IWP worse cognitive function vs. Healthy Controls (all findings nonsignificant). HC = Healthy Controls.

SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

SCID-P = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Patient Edition.

SCID-NP = Structured Clinical Interview for Non-Patients.

SCIP-II = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders.

SCAN=Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry.

CASH=Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History.

MINI = Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

DIA-X = Structured Clinical Interview.

APN = Antipsychotic Naive.

“Family” refers to first degree relatives unless otherwise specified.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

We characterized demographic and clinical variables as appropriate for antipsychotic-naïve IWP and healthy controls (Tables 1A and 1B), then by subgrouping HIC vs. LMIC. Regarding locale, 20 studies were conducted in HIC, including the US, Canada, Germany, France, UK, Denmark, Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain and Hong Kong vs. 16 studies conducted in LMIC, including China (n = 15) and South Africa (n = 1). Because we sought to characterize LMIC generally, and conducted an unrestricted search for LMIC studies, we continue to use the term “LMIC” to classify this group of studies (but interpret these studies as primarily applying to urban China—see Discussion). All but one study (Van Veelen et al., 2011) was conducted in an urban setting. Overall, the antipsychotic-naïve IWP group averaged in the low-to-mid 20's in age, 11–13 years of education, and were majority male. Clinically, DUP typically ranged from 6 to 15 months (with a typical average duration of untreated illness of 5–13 months [shortest = 2 months; longest = one outlying study of 15.2 years]), were primarily diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, typically had sample sizes from 10 to 60 (lowest = 8; highest = 256), and were recruited from inpatient or outpatient settings (Tables 1A and 1B). No major differences were noted between HIC and LMIC studies regarding age, education, DUP or duration of illness, diagnosis, or recruitment setting. LMIC studies had larger antipsychotic-naïve IWP samples (HIC largest = 86, LMIC largest = 256). The healthy controls typically averaged in the mid-20's in age, 12–15 years of education, had sample sizes from 10 to 60 (lowest = 8; highest = 540), and were majority male (Table 1A; Healthy Controls). LMIC, healthy control samples were larger than in HIC studies (LMIC largest = 540; HIC largest = 93). No major differences were noted in gender, age, or education between healthy controls in HIC vs. LMIC settings.

3.2. Characterizing cognitive impairment among antipsychotic-naïve IWP

Comparisons of cognition subtests are provided for antipsychotic-naïve IWP versus healthy controls (n = 36 studies, n = 283 distinct comparisons between cognition subtests; for this purpose, we included discrete measures [e.g. Trails A and Trails B] of related subtests).

Studies could contribute more than one comparison in a cognitive domain. Results are provided regarding total number of comparisons, and how many comparisons showed: worse cognitive performance for antipsychotic-naïve IWP; worse cognitive performance for healthy controls; and no significant differences between groups (see Table 4). “Significant differences” were based on statistical significance (i.e., which is based on the sample sizes) reported in each study. We subgrouped results by HIC vs. LMIC. When characterizing cognitive deficits by HIC vs. LMIC, we focused on key domains of executive function (processing speed), verbal declarative learning and memory performance, attention/vigilance, and working memory, which are key, separable deficits in IWP (Nuechterlein et al., 2004; Dickinson et al., 2004; Dickinson et al., 2008; Stone and Seidman, 2016).

Table 4.

Cognitive comparisons between antipsychotic-naïve individuals with psychosis and healthy controls by high vs. low and middle income countries.

| Domain | Number of Studies (N = 36) |

Number of comparisons of untreated IWP with healthy controls |

Comparisons in which untreated IWP significantly worse than healthy controls |

Comparisons in which healthy controls significantly worse than untreated IWP |

Comparisons in which untreated IWP were not significantly different than healthy controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M) Speed of Processing HIC | 10 | 24 | 20 | 0 | 4 |

| (M) Speed of Processing LMIC | 12 | 30 | 29 | 0 | 1 |

| (M) Speed of Processing Total | 22 | 54 | 49 | 0 | 5 |

| (M) Attention & Vigilance HIC | 8 | 21 | 15 | 0 | 6 |

| (M) Attention & Vigilance LMIC | 11 | 17 | 13 | 0 | 4 |

| (M) Attention & Vigilance Total | 19 | 38 | 28 | 0 | 10 |

| (M) Working Memory HIC | 7 | 18 | 17 | 0 | 1 |

| (M) Working Memory LMIC | 7 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 2 |

| (M) Working Memory Total | 14 | 30 | 27 | 0 | 3 |

| (M) Verbal Learning & Memory HIC | 6 | 26 | 16 | 0 | 10 |

| (M) Verbal Learning & Memory LMIC | 11 | 13 | 12 | 0 | 1 |

| (M) Verbal Learning & Memory Total | 17 | 39 | 28 | 0 | 11 |

| (M) Visual Learning & Memory HIC | 5 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| (M) Visual Learning & Memory LMIC | 12 | 16 | 15 | 0 | 1 |

| (M) Visual Learning & Memory Total | 17 | 22 | 20 | 0 | 2 |

| (M) Reason & Problem Solving HIC | 8 | 29 | 21 | 0 | 8 |

| (M) Reason & Problem Solving LMIC | 10 | 30 | 27 | 0 | 3 |

| (M) Reason & Problem Solving Total | 18 | 59 | 48 | 0 | 11 |

| (M) Social Cognition HIC | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| (M) Social Cognition LMIC | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| (M) Social Cognition Total | 5 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Reaction Time & Selective Attention HIC | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Reaction Time & Selective Attention LMIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reaction Time & Selective Attention Total | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Pre-morbid Verbal Estimate HIC | 3 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Pre-morbid Verbal Estimate LMIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pre-morbid Verbal Estimate Total | 3 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Visual-Perceptual Learning HIC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Visual-Perceptual Learning LMIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Visual-Perceptual Learning Total | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Procedural Learning HIC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Procedural Learning LMIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Procedural Learning Total | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Visuospatial HIC | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Visuospatial LMIC | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Visuospatial Total | 6 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| Motor Speed HIC | 4 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Motor Speed LMIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Motor Speed Total | 4 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Composite Score HIC | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Composite Score LMIC | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Composite Score Total | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTALS (Total) | 283 | 230 | 0 | 53 |

(M): MATRICS Domain

3.3. Comparison with healthy controls-main results

Cognitive performance of antipsychotic-naïve IWP was significantly impaired in the great majority (81.3%; 230/283) of comparisons with healthy controls; the remaining comparisons (18.7%; 53/283) showed no significant group differences. In no instance did antipsychotic-naïve IWP perform significantly better than healthy controls (Table 4). Out of seven MATRICS domains, six had >20 comparisons with healthy controls, with each domain showing in >70% of comparisons significantly impaired cognitive performance among antipsychotic-naïve IWP. Social cognition showed a relatively-less impaired performance among antipsychotic-naïve IWP among a limited number of comparisons (55.56%; 5/9); yet interpretation must be made cautiously, as the 4 nonsignificant findings were reported in two studies.

3.3.1. HIC vs. LMIC findings

HIC vs. LMIC comparisons are listed (Table 4). In HIC studies, cognitive performance of antipsychotic-naïve IWP was significantly impaired in >70% (73.7%; 112/152) of comparisons, with the corresponding figure in LMIC countries of >90% (90.1%; 118/131) of comparisons; remaining comparisons in HIC (26.3%; 40/152) or LMIC (9.9%; 13/131) showed no significant group differences. When examining the seven MATRICS domains, significantly impaired cognitive performance in HIC studies was found among antipsychotic-naïve IWP in 74.2% of comparisons; in LMIC studies, the corresponding figure was 89.4% of comparisons. When comparing HIC vs. LMIC studies respectively, consistent deficits appeared among IWP in the key cognitive domains of processing speed (HIC = 83.3% [20/24] vs. LMIC = 96.7% [29/30]), verbal declarative memory performance (HIC = 61.5% [16/26] vs. LMIC = 92.4% [12/13]), attention/vigilance (HIC = 71.4% [15/21] vs. LMIC = 76.5% [13/17]) and working memory (HIC = 94.4% [17/18] vs. LMIC = 83.3% [10/12]). In sum, the frequency of cognitive impairments shown among antipsychotic-naïve IWP appears to be at least as (if not slightly more) consistent in LMIC studies versus HIC studies.

3.3.2. Pre- vs. post antipsychotic medication comparisons

Overall, when examining the two pre vs. post-antipsychotic medication treatment studies (Chan et al., 2014 & Fagerlund et al., 2004), cognitive performance was significantly better post-treatment in 57% (8/14 of distinct comparisons between cognition subtests; remaining comparisons (6/14; 43%) showed no significant differences following treatment (not shown in Tables). No comparisons showed significant worsening of cognition post-treatment.

3.4. Evaluation of study methodologies

3.4.1. Application of matching procedures and methodological criteria

3.4.1.1. Comparison with healthy controls

3.4.1.1.1. Matching procedures-main results.

Overall, matching for age (54%; 20/37), gender (56%; 21/37) and in particular parental SES (16%; 6/37) were inconsistently implemented across studies comparing antipsychotic-naïve IWP vs. healthy controls (Table 2). Similarly, statistical control procedures were inconsistently utilized for age (32%; 12/37), gender (27%; 10/36), and especially parental SES (5%; 2/37) across studies. Overall, the proportion of studies not utilizing matching or statistical controls was relatively low for age (13%; 5/37) and gender (16%; 6/37); however, 78% (29/37) of studies did not utilize matching or statistical controls for parental SES.

3.4.1.2.1. HIC vs. LMIC findings.

When comparing HIC vs. LMIC studies respectively (Table 2), matching appeared comparable for age (HIC = 55% [11/20] vs. LMIC = 56.3% [9/16]) and gender (HIC = 60% [12/20] vs. LMIC = 56.3% [9/16]), with matching for parental SES appearing somewhat higher in HIC (30%; 6/20) vs. LMIC (0%; 0/16). Regarding statistical control procedures, when comparing HIC vs. LMIC studies respectively, statistical control procedures were utilized at similar or lower rates in LMIC for age (HIC = 45% [9/20] vs. LMIC = 18.8% [3/16]), gender (HIC = 25% [5/20] vs. LMIC = 31.3% [5/16]), and parental SES (HIC = 10% [2/20] vs. LMIC = 0% [0/16]). Accordingly, when comparing HIC vs. LMIC studies respectively, the proportion of studies that did not report matching procedures or statistical controls was generally at similar or higher rates for LMIC for age (HIC = 5% [1/20] vs. LMIC = 25% [4/16]), gender (HIC = 15% [3/20] vs. LMIC = 12.5% [2/16]), and for parental SES (HIC = 60% [12/20] vs. LMIC = 100% [16/16]) of studies. Hence, one trend is that while some HIC studies matched or statistically controlled for parental SES in 40% (8/20) of studies, such matching did not occur in LMIC studies (0%; 0/16).

When examining matching criteria across the three subgroups of outcomes in HIC and LMIC, studies that showed expected significant impairments in all cognition outcomes among antipsychotic-naïve IWP, as well as those that showed mixed significant and nonsignificant differences in cognition outcomes, inconsistently implemented matching criterion for age (range = 50–100%) and gender (range = 33.3%–66.7%) (Table 2). Notably, studies that failed to show any significant differences for cognition outcomes (in HIC only) did not implement matching criterion for age (0%, 0/3) or gender (0%, 0/3).

3.4.1.2. Application of methodological criteria-main results.

When examining comparisons of antipsychotic-naïve IWP versus healthy controls (Table 3), studies on average met 76% (or 3.78/5 [SD = 0.79]) of methodological criterion. Two criteria appeared problematic: most (27/36; 75%) studies used inadequate sample sizes and a substantial proportion (17/36; 47%) did not use a structured clinical interview when ascertaining healthy controls. The remaining criteria were less problematic; ≥80% studies used a structured clinical interview to identify antipsychotic-naïve IWP, nearly all studies followed either DSM-IV/TR or ICD-10 criteria, and all studies assessed clinical symptoms that might influence cognitive changes.

3.4.1.2.1. HIC vs. LMIC findings.

Among HIC, when examining comparisons of antipsychotic-naïve IWP versus healthy controls (n = 20 studies; Table 3), studies on average met 77% (or 3.85/5 [SD = 0.81]) of methodological criteria, with LMIC studies (n = 16 studies) showing a highly similar, corresponding figure of 73.8% (3.69/5 [SD = 0.79]). In both HIC and LMIC respectively, a majority of studies used inadequate sample sizes (HIC = 18/20 [90%] vs. LMIC = 9/16 [56.3%]), and a size-able proportion did not use a structured clinical interview when ascertaining healthy controls (HIC = 7/20 [35%] vs. LMIC = 10/16 [62.5%]). In contrast, in both HIC and LMIC respectively, the vast majority of studies used a structured clinical interview to identify antipsychotic-naïve IWP (HIC = 17/20 [85%] vs. LMIC = 14/16 [87.5%]) followed either DSM-IV/TR or ICD-10 criteria (HIC = 19/20 [95%] vs. LMIC = 16/16 [100%]), and assessed clinical symptoms that could influence cognitive changes (HIC = 20/20 [100%] vs. LMIC = 16/16 [100%]).

When examining methodology across the three subgroups of outcomes in HIC and LMIC, one notable finding emerged (Table 3). Studies that did not utilize adequate sample sizes (i.e., were underpowered) were most common in studies with nonsignificant differences (HIC only = 3/3, 100%) or mixed significant and nonsignificant differences (HIC = 8/8, 100%; LMIC = 3/4, 75%) in cognition outcomes, when compared with studies that showed significant impairments for antipsychotic-naïve IWP across all cognition outcomes (HIC = 7/9, 78%; LMIC = 6/12, 50%).

4. Discussion

In seeking to examine whether cognition studies in LMIC assessed first episode IWP with longer DUP and whether LMIC were broadly represented, we identified two key gaps: that LMIC study samples were primarily shorter DUP (i.e., DUP < 5 years) and were primarily conducted in urban China. Striking similarities in characteristics were exhibited in the HIC and LMIC study samples. The latter studies, like the HIC studies, were nearly all conducted in urban locales, with samples ascertained in clinic-based settings (inpatient and outpatient). Hence, while IWP with longer-term DUP are presumably accessible within LMIC and China, these studies' recruitment from urban, clinic-based settings led to sampling of typically male, young-adult, high-school educated IWP who showed shorter-term DUP, which are typical of HIC, IWP samples. This may partly be driven by urban areas of China having made recent advances in improving access to psychiatric services, and thus shortening DUP, for urban residents (although this may be less applicable to urban migrants, and to rural residents) (Phillips, 2013). Notably, both LMIC and HIC samples of IWP exhibited shorter-term DUP (typically ranging from 6 to 15 months) and DUI (typically ranging from 5 to 13 months). One difference in LMIC studies was that sample sizes of IWP and healthy controls tended to be larger when compared with HIC studies, which is reflected in the implementation of methodological criterion in LMIC studies (below). Yet similarities between LMIC and HIC samples may contribute to the overall concordance of cognitive deficits for anti-psychotic naïve IWP found in both settings. Samples of untreated IWP from urban China have shown comparable cognition deficits in other reviews (Fatorous-Bergman et al. 2014), thus suggesting that broad-based deficits are a core feature of the early course of untreated psychosis that could reflect structural brain changes reported in imaging studies (Sprooten et al., 2013), at least in these samples ascertained in urban China.

Compared with healthy controls, cognitive performance of antipsychotic-naïve IWP was significantly impaired in the great majority (81.3%; 230/283) of comparisons, with deficits among antipsychotic-naïve IWP appearing to be at least as (if not slightly more) consistent in LMIC (90.1%; 118/131]) vs. HIC studies (73.7%; 112/152]).In six of seven MATRICS domains, significant cognitive impairments appeared among antipsychotic-naïve IWP in >70% of comparisons overall, with impairments among antipsychotic-naïve IWP appearing to be at least as (if not slightly more) consistent in LMIC (89.4%) vs. HIC (74.2%) studies. The results support the presence of broadly-impaired cognitive performance among antipsychotic-naïve IWP in LMIC, corroborating prior reviews that primarily included HIC studies (Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014; Mesholam-Gately et al., 2009). Studies examining pre- vs. post-antipsychotic medication treatment on cognitive performance were rare and were conducted in HIC settings only (n = 2). Results were inconsistent, with 57% (8/14) of comparisons showing that antipsychotic-naïve participants' cognition improved after receiving medication treatment. The paucity of studies that longitudinally followed-up antipsychotic-naïve IWP (either while treated with medication, or who continued in an antipsychotic-naïve state) limited understanding of the natural trajectory of cognitive function in untreated psychosis after a first psychotic episode (below).

Regarding studies' implementation of matching procedures, a majority matched for age and gender, but a much smaller proportion (16.7%; 6/36) matched for parental SES. Further, over three-quarters of studies did not employ either matching or statistical controls for parental SES, particularly among LMIC studies (0%; 0/15). While some contradictory findings exist (Bilder et al., 2000; Galderisi et al., 2009), parental SES has been found to be associated with cognitive performance in FEP patients (Cuesta et al., 2015), and higher SES in the general population has been linked with economic resources and enriched environments, thus facilitating better brain development (Jefferson et al., 2011). We thus recommend that matching, including on parental SES, should be regularly implemented to help control for sources of variability in cognitive outcomes. On average, application of methodological criteria among comparisons with healthy controls was relatively high (76%). However, nearly 50% of studies did not use a structured clinical interview when ascertaining healthy controls, and 75% of studies used inadequate sample sizes, although this appeared less frequently in LMIC (60%; 9/15) vs. HIC (85.7%; 18/21) studies. Nearly all studies that showed “mixed” and/or “nonsignificant differences” in cognition outcomes were statistically underpowered. Hence, one key recommendation for future studies is to enroll sufficiently-powered samples of antipsychotic-naïve IWP (i.e., n ≥ 64 per group) to detect effect sizes of cognitive deficits reported by meta-analyses (Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014).

4.1. Advancing studies of antipsychotic-naïve psychosis in long-term DUP

This review characterizes, and highlights the nascent nature of, studies of cognitive deficits in antipsychotic-naïve IWP in LMIC. While most studies of antipsychotic-naïve IWP implemented basic matching (for age and gender) and methodological criterion, they frequently utilized underpowered samples of convenience. Despite these key shortcomings, we can extend to LMIC settings (albeit predominantly in urban, Chinese settings) the conclusion that antipsychotic-naïve IWP show consistent cognitive deficits compared with healthy controls. To advance understanding of the longer-term antipsychotic-naïve trajectory of cognitive decline in chronic psychotic illness (i.e., DUP > 5 years), the next generation of studies should ascertain these groups, who are more prevalent in LMIC. This requires implementing naturalistic study designs and identifying IWP within isolated rural, community settings where DUP may be longer (for notable examples, see Molina et al. (2016) in Argentina, and Ran et al., 2001, in rural China).

Longitudinal procedures should also be implemented to examine: 1) medication treatment effects upon previously antipsychotic-naïve groups, and/or; 2) the subgroups of IWP who may continue to refuse treatment due to geographic isolation or other barriers. By extending DUP past the typical shorter range shown in studies, we can examine whether the natural course of cognitive deficits in antipsychotic-naïve psychosis stabilizes after a first psychotic episode or progressively declines as DUP increases. Naturally, ethical issues including providing adequate treatment must be carefully addressed when initiating engagement with antipsychotic-naïve IWP (e.g., via free medication treatment for IWP offered by some national treatment programs, such as the “686 Program” in China (Phillips, 2013).

4.2. Limitations and future directions

First, while identified as a key finding of our systematic review, most studies in the LMIC category, as in the Fatouros-Bergman et al. (2014) meta-analysis, were predominantly conducted in urban China. While limiting representation of LMIC countries, this highlights the need to broaden cognition studies conducted in LMIC beyond China. Another limitation is the exclusion of foreign language articles, which may have underestimated the number of studies conducted within non-English-speaking LMICs. While we utilized previously-developed standards for treatment trials for cognition studies with IWP to assess study methodology (Harvey and Keefe, 2001), our review highlights the need to establish agreed-upon standards to evaluate cognition studies. Our count of number of methodological criteria met by studies served as a proxy measure of study quality. Although we sought to examine cognition of IWP in diverse LMIC regions, our search strategy only yielded studies from urban, LMIC areas. While we could have identified more LMIC studies by including studies that only assessed composite cognition scores, we did not do so because examining domain-specific cognitive deficits comprised a central aim. Some notable cognition studies in rural LMIC (e.g., Molina et al., 2016) were excluded because we did not have access to the original data and could not statistically verify pre- vs. post antipsychotic treatment differences. Because identified studies ascertained clinic-based samples of convenience, findings were specific to younger, educated, urban IWP in LMIC. Lastly, it would be important for future studies to assess measures of subjective outcomes in relation to cognitive deficits (e.g., quality of life).

Methodologically advancing future studies of antipsychotic-naïve IWP could enhance understanding of the core pathophysiologies associated with functional decline in psychosis. Hence, understanding potential cognitive decline associated with longer-term DUP, and its potential response to medication treatment, remains crucial. We hope this review spurs innovations in future studies to address questions relevant to antipsychotic-naïve IWP in rural LMIC settings, who are likely to comprise the majority of untreated IWP worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Pinky Li, Marianne Broeker, and Sandy Liu for their assistance in formatting the tables and manuscript. Dr.'s Yang, Phillips, Susser, Keshavan, Stone and Seidman were supported by funds from NIMH R01-MH108385 (PI: Yang, mPI: Phillips, mPI: Keshavan) entitled “Characterizing Cognition across the Lifespan in Untreated Psychosis in China.” Dr. Lieberman was supported by funds from NIMH 1U01MH121766-01 and NIMH 1R01 MH113861-01. We also dedicate this manuscript posthumously to beloved friend and collaborator, Larry Seidman.

Role of funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the design of the review, collection of articles, synthesis of articles, interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all articles in the review and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.01.026.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study. We declare that no authors have support from any company for the submitted work. Dr.'s Yang, Phillips, Susser, Keshavan, Stone and Seidman were supported by funds from NIMH R01-MH108385 (PI: Yang) entitled “Characterizing Cognition across the Lifespan in Untreated Psychosis in China.”

References

- Aikawa S, Kobayashi H, Nemoto T, Matsuo S, Wada Y, Mamiya N, … Mizuno M, 2018. Social anxiety and risk factors in patients with schizophrenia: relationship with duration of untreated psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 263, 94–100. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allott K, Fraguas D, Bartholomeusz CF, Díaz-Caneja CM, Wannan C, Parrish EM, Amminger GP, Pantelis C, Arango C, McGorry PD, Rapado-Castro M, 2018. Duration of untreated psychosis and neurocognitive functioning in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological medicine 48 (10), 1592–1607. 10.1017/S0033291717003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R, Fagerlund B, Rasmussen H, Ebdrup BH, Aggernæs B, Gade A, Glenthoj B, 2013. The influence of impaired processing speed on cognition in first-episode antipsychotic-naive schizophrenic patients. Eur. Psychiatry 28 (6), 332–339. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anhøj S, Ødegaard Nielsen M, Jensen MH, Ford K, Fagerlund B, Williamson P, Rostrup E, 2018. Alterations of intrinsic connectivity networks in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 44 (6), 1332–1340. 10.1093/schbul/sbx171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anilkumar AP, Kumari V, Mehrotra R, Aasen I, Mitterschiffthaler MT, Sharma T, 2008. An fMRI study of face encoding and recognition in first-episode schizophrenia. Acta neuropsychiatrica 20 (3), 129–138. 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2008.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnado I, Olié JP, 2006. Effects of disorganization on choice reaction time and visual orientation in untreated schizophrenics. Dialogues in clinical neurosci. 8 (1), 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, Reiter G, Bell L, Bates JA, … Geisler S, 2000. Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: initial characterization and clinical correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry 157 (4), 549–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Neale JM, 1994. The neuropsychological signature of schizophrenia: generalized or differential deficit? Am. J. Psychiatry 151 (1), 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boksman K, Théberge J, Williamson P, Drost DJ, Malla A, Densmore M, Neufeld RW, 2005. A 4.0-T fMRI study of brain connectivity during word fluency in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 75 (2–3), 247–263. 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yücel M, Pantelis C, 2009. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia and affective psychoses: implications for DSM-V criteria and beyond. Schizophr. Bull sbp094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yalincetin B, Akdede BB, Alptekin K, 2018. Duration of untreated psychosis and neurocognition in first-episode psychosis: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research 193, 3–10. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Buchsbaum MS, Bloom R, Bokhoven P, Paul-Odouard R, Haznedar MM, Shihabuddin L, 2004. Neuropsychological functioning in first-break, never-medicated adolescents with psychosis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 192 (9), 615–622. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138229.29157.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cechnicki A, Cichocki Ł, Kalisz A, Błądziński P, Adamczyk P, Franczyk-Glita J, 2014. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the course of schizophrenia in a 20-year follow-up study. Psychiatry research 219 (3), 420–425. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RC, Chen EY, Law CW, 2006. Specific executive dysfunction in patients with first-episode medication-naive schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 82 (1), 51–64. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SKW, Chan KKS, Hui CL, Wong GHY, Chang WC, Lee EHM, Chen EYH, 2014. Correlates of insight with symptomatology and executive function in patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorder: a longitudinal perspective. Psychiatry Res. 216 (2), 177–184. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WC, Hui CLM, Tang JYM, Wong GHY, Chan SKW, Lee EHM, Chen EYH, 2013. Impacts of duration of untreated psychosis on cognition and negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia: a 3-year prospective follow-up study. Psychological. Medicine 43 (9), 1883–1893. 10.1017/S0033291712002838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Jiang W, Zhong N, Wu J, Jiang H, Du J, … & Gao C (2014). Impaired processing speed and attention in first-episode drug naive schizophrenia with deficit syndrome. Schizophr. Res, 159(2–3), 478–484. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta MJ, Sánchez-Torres AM, Cabrera B, Bioque M, Merchán-Naranjo J, Corripio I, Sanjuan J, 2015. Premorbid adjustment and clinical correlates of cognitive impairment in first-episode psychosis. The PEPsCog study. Schizophr. Res. 164 (1–3), 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Iannone VN, Wilk CM, Gold JM, 2004. General and specific cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 55 (8), 826–833. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Ragland JD, Gold JM, Gur RC, 2008. General and Specific Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia: Goliath Defeats David? Biological Psychiatry 64, 823–827. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R, Asmal L, du Plessis S, Chiliza B, Kidd M, Carr J, Vink M, 2015. Dorsal striatal volumes in never-treated patients with first-episode schizophrenia before and during acute treatment. Schizophr. Res 169 (1–3), 89–94. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerlund B, Mackeprang T, Gade A, Hemmingsen R, Glenthøj BY, 2004. Effects of low-dose risperidone and low-dose zuclopenthixol on cognitive functions in first-episode drug-naive schizophrenic patients. CNS spectrums 9 (5), 364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatouros-Bergman H, Cervenka S, Flyckt L, Edman G, Farde L, 2014. Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 158 (1), 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forest G, Poulin J, Daoust AM, Lussier I, Stip E, Godbout R, 2007. Attention and non-REM sleep in neuroleptic-naive persons with schizophrenia and control participants. Psychiatry Res. 149 (1–3), 33–40. 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galderisi S, Davidson M, Kahn RS, Mucci A, Boter H, Gheorghe MD, Rybakowski JK, Libiger J, Dollfus S, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Peuskens J, Hranov LG, Fleischhacker WW, 2009. Correlates of cognitive impairment in first episode schizophrenia: the EUFEST study. Schizophr. Res. 115 (2–3), 104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Zeng B, Ardekani BA, Diminich ED, Tang Y, Fan X, Wang J, 2018. Association of hippocampal atrophy with duration of untreated psychosis and molecular biomarkers during initial antipsychotic treatment of first-episode psychosis. JAMA Psychiat. 75 (4), 370–378. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Harvey PD, 1993. Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Clin. 16 (2), 295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, 1996. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am. J. Psychiatry 153 (3), 321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Li J, Wang J, Fan X, Hu M, Shen Y, Zhao J, 2014. Hippocampal and orbital inferior frontal gray matter volume abnormalities and cognitive deficit in treatment-naive, first-episode patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 152 (2–3), 339–343. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, Wiseman CL, Reilly JL, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA, 2009. Effects of risperidone on procedural learning in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 34 (2), 468. 10.1038/npp.2008.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Keefe RS, 2001. Studies of cognitive change in patients with schizophrenia following novel antipsychotic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 158 (2), 176–184. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Deng W, Li M, Chen Z, Jiang L, Wang Q, Zhang N, 2013. Aberrant intrinsic brain activity and cognitive deficit in first-episode treatment-naive patients with schizophrenia. Psychol. Med 43 (4), 769–780. 10.1017/S0033291712001638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK, 1998. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology 12 (3), 426. 10.1037/0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SK, Beers SR, Kmiec JA, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA, 2004a. Impairment of verbal memory and learning in antipsychotic-naıve patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 68 (2–3), 127–136. 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SK, Keshavan MS, Thase ME, Sweeney JA, 2004b. Neuropsychological dysfunction in antipsychotic-naive first-episode unipolar psychotic depression. Am. J. Psychiatr 161 (6), 996–1003. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilti CC, Delko T, Orosz AT, Thomann K, Ludewig S, Geyer MA, Cattapan-Ludewig K, 2010. Sustained attention and planning deficits but intact attentional set-shifting in neuroleptic-naïve first-episode schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychobiology 61 (2), 79–86. 10.1159/000265133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Chen J, Li L, Zheng Y, Wang J, Guo X, Zhao J, 2011. Semantic fluency and executive functions as candidate endophenotypes for the early diagnosis of schizophrenia in Han Chinese. Neurosci. Lett 502 (3), 173–177. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Huang Y, Yu L, Hu J, Chen J, Jin P, … Xu Y, 2016. Relationship between negative symptoms and neurocognitive functions in adolescent and adult patients with first-episode schizophrenia. BMC psychiatry 16 (1), 344. 10.1186/s12888-016-1052-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ML, Khoh TT, Lu SJ, Pan F, Chen JK, Hu JB, Qi HL, 2017. Relationships between dorsolateral prefrontal cortex metabolic change and cognitive impairment in first-episode neuroleptic-naive schizophrenia patients. Medicine 96 (25). 10.1097/MD.0000000000007228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson AL, Gibbons LE, Rentz DM, Carvalho JO, Manly J, Bennett DA, Jones RN, 2011. A life course model of cognitive activities, socioeconomic status, education, reading ability, and cognition. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 59 (8), 1403–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Silva SG, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA, 1999. The effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull 25 (2), 201–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Haas G, Miewald J, Montrose DM, Reddy R, Schooler NR, Sweeney JA, 2003. Prolonged untreated illness duration from prodromal onset predicts outcome in first episode psychoses. Schizophr. Bull 29 (4), 757–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger S, Lis S, Cetin T, Gallhofer B, Meyer-Lindenberg A, 2005. Executive function and cognitive subprocesses in first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenia: an analysis of N-back performance. Am. J. Psychiatr 162 (6), 1206–1208. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruiper C, Fagerlund B, Nielsen MØ, Düring S, Jensen MH, Ebdrup BH, Oranje B, 2019. Associations between P3a and P3b amplitudes and cognition in antipsychotic-naïve first-episode schizophrenia patients. Psychol. Med 49 (5), 868–875. 10.1017/S0033291718001575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt JJ, McCarley RW, Dickey CC, Voglmaier MM, Niznikiewicz MA, Seidman LJ, … & Shenton ME (2002). MRI study of caudate nucleus volume and its cognitive correlates in neuroleptic-naive patients with schizotypal personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatr, 159(7), 1190–1197. doi.org/ 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Guo W, Zhang Y, Lv L, Hu F, Wu R, Zhao J, 2018. Decreased resting-state interhemispheric functional connectivity correlated with neurocognitive deficits in drug-naive first-episode adolescent-onset schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21 (1), 33–41. 10.1093/ijnp/pyx095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Zhang C, Yi Z, Li Z, Wu Z, Fang Y, 2012. Association between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and cognitive performance in antipsychotic-naive patients with schizophrenia. J. Mol. Neurosci 47 (3), 505–510. 10.1007/s12031-012-9750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man L, Lv X, Du XD, Yin G, Zhu X, Zhang Y, Zhang XY, 2018. Cognitive impairments and low BDNF serum levels in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 263, 1–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreadie RG, Thara R, Padmavati R, Srinivasan TN, Jaipurkar SD, 2002. Structural brain differences between never-treated patients with schizophrenia, with and without dyskinesia, and normal control subjects: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59 (4), 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, 2009. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology 23 (3), 315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med 151 (4), 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina JL, González Alemán G, Florenzano N, Padilla E, Calvó M, Guerrero G, Hernández Cuervo H, 2016. Prediction of neurocognitive deficits by parkinsonian motor impairment in schizophrenia: a study in neuroleptic-naïve subjects, unaffected first-degree relatives and healthy controls from an indigenous population. Schizophr. Bull 42 (6), 1486–1495. 10.1093/schbul/sbw023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossaheb N, Schäfer MR, Schlögelhofer M, Klier CM, Cotton SM, McGorry PD, Amminger GP, 2013. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of young patients at risk for psychosis: when do they begin to be effective? Schizophrenia Research 148 (1–3), 163–167. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejad AB, Ebdrup BH, Siebner HR, Rasmussen H, Aggernæs B, Glenthøj BY, Baaré WF, 2011. Impaired temporoparietal deactivation with working memory load in antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 12 (4), 271–281. 10.3109/15622975.2010.556199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK, 2004. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 72 (1), 29–39. 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Goldberg T, 2008. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am. J. Psychiatr 165 (2), 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttilä M, Jääskeläinen E, Hirvonen N, Isohanni M, Miettunen J, 2014. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 205 (2), 88–94. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.127753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MR, 2013. Can China’s new mental health law substantially reduce the burden of illness attributable to mental disorders ? Lancet 381 (9882), 1964–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]