Abstract

BACKGROUND

Burden due to intellectual disability (ID) is only third to the depressive disorders and anxiety disorders in India. This national burden significantly contributes to the global burden of ID and hence one has to think globally and act locally to reduce this burden. At its best the collective prevalence of ID is in the form of narrative reviews. There is an urgent need to document the summary prevalence of ID to enhance further policymaking, national programs and resource allocation.

AIM

To establish the summary prevalence of ID during the past 60 years in India.

METHODS

Two researchers independently and electronically searched PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane library from January 1961 to December 2020 using appropriate search terms. Two other investigators extracted the study design, setting, participant characteristics, and measures used to identify ID. Two other researchers appraised the quality of the studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal format for Prevalence Studies. Funnel plot and Egger’s regression test were used to ascertain the publication and small study effect on the prevalence. To evaluate the summary prevalence of ID, we used the random effects model with arcsine square-root transformation. Heterogeneity of I2 ≥ 50% was considered substantial and we determined the heterogeneity with meta-regression. The analyses were performed using STATA (version 16).

RESULTS

Nineteen studies were included in the meta-analysis. There was publication bias; the trim-and-fill method was used to further ascertain bias. Concerns with control of confounders and the reliable measure of outcome were noted in the critical appraisal. The summary prevalence of ID was 2% [(95%CI: 2%, 3%); I2 = 98%] and the adjusted summary prevalence was 1.4%. Meta-regression demonstrated that age of the participants was statistically significantly related to the prevalence; other factors did not influence the prevalence or heterogeneity.

CONCLUSION

The summary prevalence of ID in India was established to be 2% taking into consideration the individual prevalence studies over the last six decades. This knowledge should improve the existing disability and mental health policies, national programs and service delivery to reduce the national and global burden associated with ID.

Keywords: India, Intellectual disability, Prevalence, Children and adolescents, Meta-analysis

Core Tip: Intellectual disability (ID) is prevalent in India and earlier epidemiological studies on mental disorders have documented the lifetime prevalence of ID. However, the documented prevalence of ID in the country shows a wide range. The burden posed by ID is only third to the depressive disorders and anxiety disorders among mental disorders. The burden of ID in India significantly contributes to the global burden of ID; to decrease this we need to think globally and act locally in an evidence-based manner. To date, the prevalence of ID in India has been shown in narrative reviews. This suggests that the summary prevalence of ID in India has to be ascertained to help improve the existing disability and mental health policies, national programs and service delivery. This meta-analysis established that the summary lifetime prevalence of ID in India is 2%.

INTRODUCTION

Intellectual disability (ID) contributes to 10.8% of the burden of mental disorders, measured by disability-adjusted life-years, in India. The burden caused by ID in India is only third to the depressive disorders and anxiety disorders[1]. Improving access to evidence-based mental health services for those with mental disorders is the best approach to address the burden of mental disorders in India[2]. However, the evidence based data for ID is difficult to build and most of the prevalence reviews for ID in India are narrative.

In narrative reviews, ID is prevalent in 1%-3.2% of the population in India depending on the definition of prevalence, study population, study design, and measures used to identify ID[3]. Among individual studies, the prevalence of ID in the country varied from 0.28%-20%[4,5]. This variation in prevalence is significant and does not help in planning precise policies, national programs and service delivery models for ID; the best way forward is to determine the summary prevalence of ID in India.

The summary prevalence of ID has not been documented in India and only an attempt to extrapolate from the 2002 Disability data report of the National Sample Survey Organization was made[6]. This meta-analysis documents the summary prevalence of ID in India for policy making and developing nation-wide clinical programs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

Two researchers (Chikkala SM and Earnest R) independently and electronically searched for relevant published studies in PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane library over the past 60 years (January 1961 to December 2020). The search terms were as follows: “prevalence of intellectual disability in India”, combined and included as: ("epidemiology"[MeSH Subheading] OR "epidemiology"[All Fields] OR "prevalence"[All Fields] OR "prevalence"[MeSH Terms] OR "prevalance"[All Fields] OR "prevalences"[All Fields] OR "prevalence s"[All Fields] OR "prevalent"[All Fields] OR "prevalently"[All Fields] OR "prevalents"[All Fields]) AND ("intellectual disability"[MeSH Terms] OR ("intellectual"[All Fields] AND "disability"[All Fields]) OR "intellectual disability"[All Fields]) AND ("india"[MeSH Terms] OR "india"[All Fields] OR "india s"[All Fields] OR "indias"[All Fields]). In addition, a hand-search was conducted for any potential study for inclusion from cross references and conference publications.

Study selection and data extraction

The studies retrieved during the searches were screened for relevance, and those identified as being potentially eligible were fully assessed for inclusion/exclusion from the titles. Two researchers (Russell S and Shankar SR) individually extracted the required data from the studies selected from inclusion. Any difference in the data extracted between the researchers was resolved through consultation with a third researcher (Mammen PM). Details on the prevalence of ID, sampling method, sample size, participant characteristics; setting of the study, definition of ID (borderline intelligence was excluded) measures/criteria used for diagnosis of ID, from each study were extracted. To be included in the final analysis, the studies required all these details available for extraction. Those studies with age of participant above 18 years, hospital setting and participants with borderline intelligence but not ID, and studies carried out on special illness populations were excluded.

Quality appraisal and risk of bias

Two researchers (Nagaraj S and Vengadavaradan A) independently appraised the studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data for the quality of the studies included in the final analysis[7]; and any discrepancies in the critical appraisal was resolved by consensus through discussion with another researcher (Mammen PM). A contour-enhanced funnel plot was developed for publication bias and Egger’s regression analysis was performed for the analysis of small study bias[8].

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the summary prevalence, we used the random effects model with arcsine square-root transformation; heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50%) was expected to be substantial in this prevalence meta-analysis and hence the transformation was used. As the contour-enhanced funnel plot and Egger’s regression test demonstrated significant publication bias, as a post hoc test, the trim-and-fill technique was used to explore the nature of the bias[9]. We determined the heterogeneity with meta-regression. The analyses were carried out using the STATA (version 16) software package.

RESULTS

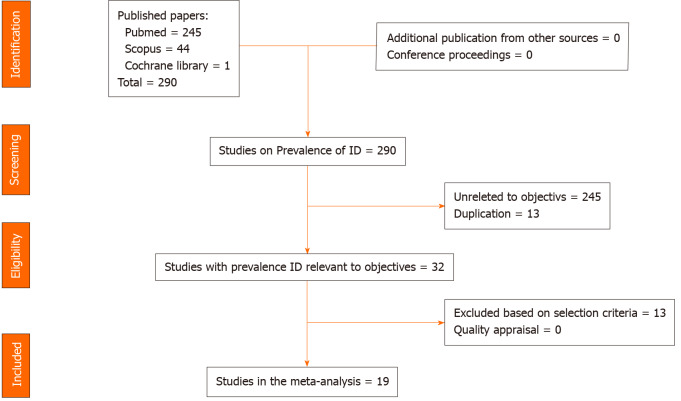

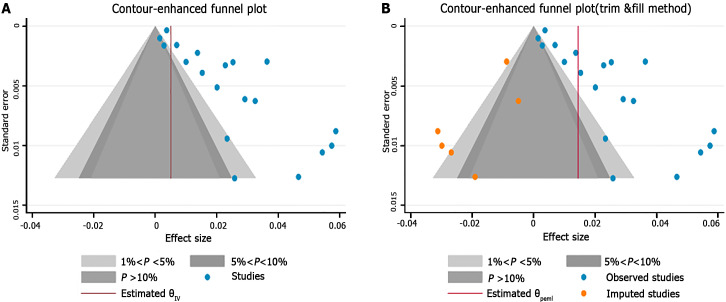

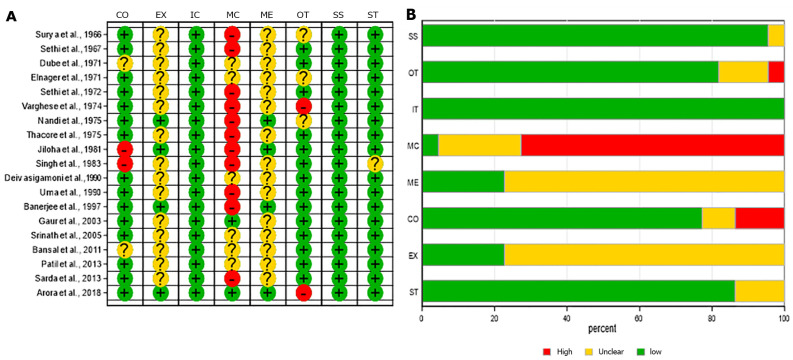

In total, we identified 290 studies from all the databases and 19 studies[10-28] were included in the final meta-analysis. Thirteen studies were excluded as they had either age group above 18 years and ID prevalence could not be calculated, a setting other than community or school, or the prevalence was studied in specific disease populations. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) details regarding the selection of studies for the final analysis are presented in Figure 1; the methodology and prevalence data are given in Table 1. The visual examination of the contour-enhanced funnel plot (Figure 2A) and the Egger’s test [coefficient = 5.92 (standard error = 1.19), t = -5.0; P = 0.0001] revealed publication bias or a small study effect, respectively, on the prevalence of ID in India. The trim-and-fill method demonstrated that four more studies were required on the left side of the funnel to overcome this bias (Figure 2B). The JBI critical appraisal for each study and the average quality included in the final analysis are depicted in Figure 3. Concerns with control of confounders and reliable measurement of outcome were noted in the critical appraisal as common biases.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow-chart for studies in the final meta-analysis.

Table 1.

The methodological and prevalence details of included studies

|

Ref.

|

Area; setting

|

Age(yr)

|

Sampling, diagnostic method

|

Prevalence of ID (%)

|

Sample size

|

| Surya et al[10] | Urban; community | 0-15 | Screening schedule + CI | 0.7 | 2731 |

| Sethi et al[11] | Urban; community | 0-10 | Comprehensive questionnaire + CI | 5.74 | 541 |

| Dube et al[12] | Mixed; community | 44693 | CI | 0.37 | 8035 |

| Elnagar et al[11] | Rural; community | 0-14 | CI + WHO ECH | 0.86 | 635 |

| Sethi et al[14] | Rural; community | 0-10 | Comprehensive questionnaire, CI | 6.84 | 877 |

| Verghese et al[15] | Urban; community | 44663 | Comprehensive questionnaire + ICD-9 | 2.01 | 747 |

| Nandi et al[16] | Rural; community | 0-11 | Comprehensive questionnaire + WHO ECH | 0.28 | 462 |

| Thacore et al[17] | Urban; community | 0-15 | CI + DSM II | 2.94 | 2696 |

| Jiloha et al[18] | Rural; school | 44693 | Comprehensive questionnaire + ICD-9 | 5.87 | 715 |

| Singh et al[19] | Urban; community | 44575 | CI + ICD-9 | 4.7 | 279 |

| Deivasigamani et al[20] | Urban; school | 44785 | Rutter B + ICD 9 | 2.9 | 755 |

| Uma et al[21] | Mixed; School | 44624 | PBCL (parent version) | 2.91 | 155 |

| Banerjee et al[22] | Urban; school | 44783 | CI + CBQ + ICD-9 | 5.4 | 460 |

| Gaur et al[23] | Mixed; community | 44726 | CPMS + DISC + ICD-10 schedule | 3.25 | 800 |

| SriP-Editornath et al[24] | Mixed; community | 0-16 | CBCL + DISC + VSMS + CGAS + ICD-10 | 2.3 | 2064 |

| Bansal et al[25] | Rural; community | 44849 | CPMS +ICD-10 | ||

| Patil et al[26] | Urban; community | 44695 | CI + DSM-IV | 2.4 | 257 |

| Sarda et al[27] | Mixed; school | 44667 | CBS + CBCL + DISC + ICD-10 | 0.99 | 1110 |

| Arora et al[28] | Mixed; community | INCLEN Measures + DSM-IV-TR | 3.6 | 3964 |

CI: Clinical Interview; CBQ: Children’s Behaviour Questionnaire; CBCL: Child Behaviour Check List; CPMS: Indian Adaptation of CBCL; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (edition IV and IV-TR); CGAS: Children’s Global Assessment Scale; DISC: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; ECH: WHO expert committee on mental health criteria; ICD: International Classification of Diseases (edition 9 and 10); INCLEN: The International Clinical Epidemiology Network; PBCL: Preschool Behaviour Check List; VSMS: Vineland Social Maturity Scale.

Figure 2.

The contour-enhanced funnel plot (A) and trim-and-fill plot (B) for publication bias.

Figure 3.

The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal for prevalence meta-analysis for individual studies (A) and average quality across studies (B). IC: Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? SS: Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? EX: Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? ME: Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? CO: Were confounding factors identified? MC: were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? OT: Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? ST: Was appropriate statistical analysis used? High: High bias; No: Low bias; Unclear: Unclear bias; NA: Not applicable.

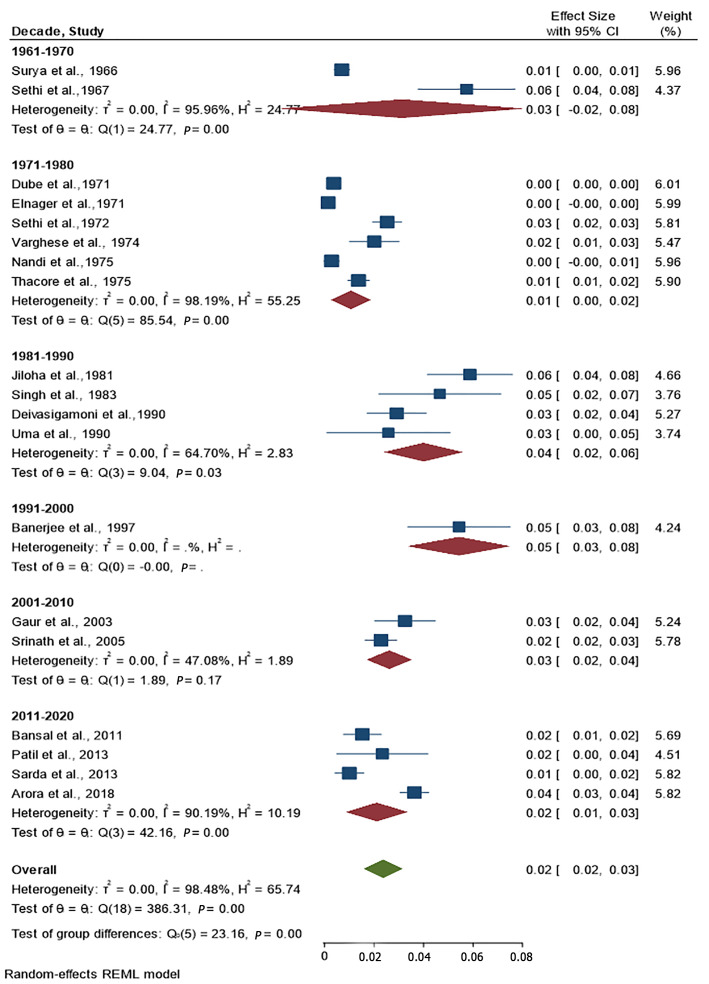

The summary prevalence of ID among children and adolescents in India was 2% [0.02 (95%CI: 0.02%, 0.03%); I2 = 98%] and is presented as a forest plot (Figure 4). When the required six studies were included using the trim-and-fill method, the imputed prevalence of ID in India was 1.4%. The prevalence of ID has changed over the last 60-year period in India from 5% to 2%.

Figure 4.

The forest plot for summary prevalence of intellectual disability in India.

There was substantial heterogeneity in the meta-analysis; our meta-regression demonstrated that the heterogeneity between the prevalence studies was statistically significantly related to the age of the participants (children vs adolescents; coefficient =-0.019 (s.e) =0.009; P = 0.03), the area of residence or school, setting of the study in the community or school, and the diagnostic assessment used was not significantly related to the prevalence of ID.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis documents that the summary life-time prevalence of ID is 2% and the adjusted summary life-time prevalence is 1.4% in India. This prevalence is, thus, within the range of 1%-3% in the narrative review[3] and the extrapolated data of 1.5% from the National Sample Survey Organization by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India[6]. With the above epidemiological insights, it is important to mitigate the burden with prevention and effective habilitation.

The lifetime prevalence of ID despite being small when compared with many other development disabilities of childhood[28], the burden caused by this disability is a significant 10.8% among mental disorders in India. The population size of India is so huge this burden adds to the global burden of ID; therefore, it has been suggested to enhance the disability programs to have sustainable burden reduction practices at the national level[29].

This meta-analysis was based on only published studies in the English language. Our funnel plot and test for the influence of small studies was significant and six more studies were required to prevent the publication and small study bias. However, we used the trim and fill method to impute the number of studies required to improve this meta-analysis and adjust the prevalence in our study. Thus, in this meta-analysis, the impact of four missing studies was simulated, and the original prevalence of 2% was revised to an adjusted prevalence of 1.4%.

From the utility perspective of this meta-analysis, it is important that the systematic survey we carried out as part of the meta-analysis shows there is a significant paucity of studies on the prevalence of ID in certain states of India. Moreover, the mental health programs at the national and state levels in India have to bridge the gap between identification and management need of those with ID, with focused polices, programs and capacity building. Although there has been noticeable progress in the policy, national program, and service programs, most of them are focused on the secondary and tertiary prevention of ID[3]. It has been documented that up to 25% of ID is preventable in India and 305 are acquired forms of ID[30]; this underscores the need for approaches such as the modified Finnish method in the context of identifying the aetiology of ID in India[31].

The findings of this study should be interpreted from the perspective of the lifetime prevalence of ID. We decided on this definition to build the systematic-survey, as ID is a lifetime condition, where the condition can be improved but cannot be reversed[32]. Secondly, although we searched for grey literature we did not search for unpublished data and thus could have limited the national data on this disorder.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the lifetime prevalence of ID in India is consistent with narrative reviews. Addressing the ID burden requires delivery of integrated disability and mental health care services at the community level. This summary lifetime prevalence should further enhance policymaking and resource allocation for ID in India.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

India has a population of more than one billion with a significant disability burden similar to other low- and middle-income countries. The summary prevalence of intellectual disability (ID) in India has not been established.

Research motivation

ID contributes to 10.8% of the burden due to mental disorders in India. This national burden significantly contributes to the global burden of ID and hence one has to think globally and act locally to reduce this burden. At its best the collective prevalence of ID is in the form of narrative reviews. There is an urgent need to document the summary prevalence of ID to enhance further policymaking, national programs and resource allocation.

Research objectives

The aim of the meta-analysis was to establish the summary prevalence of ID in India over the past 60 years.

Research methods

Nineteen studies were included in the meta-analysis following the PRISMA guidelines. To analyse the summary prevalence of ID, we used the random effects model with arcsine square-root transformation. Heterogeneity of I2 ≥ 50% was considered substantial and we determined the heterogeneity with meta-regression.

Research results

The summary prevalence of ID was 2% [(95%CI: 2%, 3%); I2 = 98%] and the adjusted summary prevalence was 1.4%. Meta-regression demonstrated that age of the participants was statistically significantly related to the prevalence; other factors did not influence the prevalence or heterogeneity.

Research conclusions

The authors established the summary prevalence of ID in India as 2% taking into consideration the individual prevalence studies over the last 6 decades. This knowledge should improve the existing disability and mental health policies, national programs and service delivery models to mitigate the burden related to ID.

Research perspectives

Future research should focus on the role of the summary prevalence of ID in the reduction of burden due to this disability in India and globally.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 21, 2021

First decision: May 6, 2021

Article in press: February 11, 2022

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Swai JD S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Cai YX

Contributor Information

Paul Swamidhas Sudhakar Russell, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India. russell@cmcvellore.ac.in.

Sahana Nagaraj, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Ashvini Vengadavaradan, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Sushila Russell, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Priya Mary Mammen, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Satya Raj Shankar, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Shonima Aynipully Viswanathan, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Richa Earnest, Department of Psychiatry, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Swetha Madhuri Chikkala, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

Grace Rebekah, Department of Biostatistic, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 002, Tamil Nadu, India.

References

- 1.India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Mental Disorders Collaborators. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:148–161. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shidhaye R. Unburden mental health in India: it's time to act now. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:111–112. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girimaji SC, Srinath S. Perspectives of intellectual disability in India: epidemiology, policy, services for children and adults. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:441–446. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833ad95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nandi DN, Banerjee G, Mukherjee SP, Sarkar S, Boral GC, Mukherjee A, Mishra DC. A study of psychiatric morbidity of a rural community at an interval of ten years. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:179–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lal N, Sethi BB. Estimate of mental ill health in children of an urban community. Indian J Pediatr. 1977;44:55–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02753627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakhan R, Ekúndayò OT, Shahbazi M. An estimation of the prevalence of intellectual disabilities and its association with age in rural and urban populations in India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015;6:523–528. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.165392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, Stephenson M, Aromataris E. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2127–2133. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surya NC, Datta SP, Gopalakrishnan R, Sundaram D, Kutty J. Mental morbidity in Pondicherry (1962-63) Trans All India Institute . 4:50– 61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Kumar R. Three hundred urban families - a psychiatric study. Indian J Psychiatry . 1967;9:280. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dube KC. A study of prevalence and biosocial variables in mental illness in a rural and an urban community in Uttar Pradesh--India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;46:327–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elnagar MN, Maitra P, Rao MN. Mental health in an Indian rural community. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;118:499–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.118.546.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Kumar R, Kumarr P. A psychiatric survey of 500 rural families. Indian J Psychiatry. 1972;14:183–196. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verghese A, Beig A. Psychiatric disturbance in children--an epidemiological study. Indian J Med Res. 1974;62:1538–1542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nandi N, Aimany S, Ganguly H, Banerjee G, Boral GC, Ghosh A, Sarkar S. Psychiatric disorder in a rural community in West Bengal: An epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thacore VR, Gupta SC, Suraiya M. Psychiatric morbidity in a north Indian community. Br J Psychiatry. 1975;126:365–369. doi: 10.1192/bjp.126.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiloha RC, Murthy RS. An epidemiological study of psychiatric problems in primary school children. Child Psychiatry Quarterly. 1981;14:108–119. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh AJ, ShuWaj D, Verma BI, Kumar A, Srivastava N. An epidemiological study in childhood psychiatric disorders. Indian Pediatr. 1983;20:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deivasigamani TR. Psychiatric morbidity in primary school children - an epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32:235–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uma H, Kapur M. A Study of Behaviour Problems in Pre-School Children. NIMHANS J. 1990;8:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee T. Psychiatric morbidity among rural primary school children in west bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:130–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaur DR, Vohra AK, Subhash S and Khurana H. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among 6-14 years old children. Indian J Community Med. 2003;28:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srinath S, Girimaji SC, Gururaj G, Seshadri S, Subbakrishna DK, Bhola P, Kumar N. Epidemiological study of child & adolescent psychiatric disorders in urban & rural areas of Bangalore, India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bansal PD, Barman R. Psychopathology of school going children in the age group of 10-15 years. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2011;1:43–47. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.81980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil RN, Nagaonkar SN, Shah NB, Bhat TS. A Cross-sectional Study of Common Psychiatric Morbidity in Children Aged 5 to 14 Years in an Urban Slum. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2:164–168. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.117413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarda R, Kimmatkar N, Hemnani JT, Hemnani TJ, Mishra P, Jain SK. Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in Western U.P. Region- A School Based Study. Int J Sci Study . 2013;1:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arora NK, Nair MKC, Gulati S, Deshmukh V, Mohapatra A, Mishra D, Patel V, Pandey RM, Das BC, Divan G, Murthy GVS, Sharma TD, Sapra S, Aneja S, Juneja M, Reddy SK, Suman P, Mukherjee SB, Dasgupta R, Tudu P, Das MK, Bhutani VK, Durkin MS, Pinto-Martin J, Silberberg DH, Sagar R, Ahmed F, Babu N, Bavdekar S, Chandra V, Chaudhuri Z, Dada T, Dass R, Gourie-Devi M, Remadevi S, Gupta JC, Handa KK, Kalra V, Karande S, Konanki R, Kulkarni M, Kumar R, Maria A, Masoodi MA, Mehta M, Mohanty SK, Nair H, Natarajan P, Niswade AK, Prasad A, Rai SK, Russell PSS, Saxena R, Sharma S, Singh AK, Singh GB, Sumaraj L, Suresh S, Thakar A, Parthasarathy S, Vyas B, Panigrahi A, Saroch MK, Shukla R, Rao KVR, Silveira MP, Singh S, Vajaratkar V. Neurodevelopmental disorders in children aged 2-9 years: Population-based burden estimates across five regions in India. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dandona R, Pandey A, George S, Kumar GA, Dandona L. India's disability estimates: Limitations and way forward. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0222159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinath S, Girimaji SC. Epidemiology of child and adolescent mental health problems and mental retardation. NIMHANS J . 1999;17:355–366. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kishore MT, Udipi GA, Seshadri SP. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Assessment and Management of intellectual disability. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:194–210. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_507_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Streiner DL, Patten SB, Anthony JC, Cairney J. Has 'lifetime prevalence' reached the end of its life? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18:221–228. doi: 10.1002/mpr.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]