Abstract

Two ampicillin-resistant (Ampr) isolates of Vibrio harveyi, W3B and HB3, were obtained from the coastal waters of the Indonesian island of Java. Strain W3B was isolated from marine water near a shrimp farm in North Java while HB3 was from pristine seawater in South Java. In this study, novel β-lactamase genes from W3B (blaVHW-1) and HB3 (blaVHH-1) were cloned and their nucleotide sequences were determined. An open reading frame (ORF) of 870 bp encoding a deduced protein of 290 amino acids (VHW-1) was revealed for the bla gene of strain W3B while an ORF of 849 bp encoding a 283-amino-acid protein (VHH-1) was deduced for blaVHH-1. At the DNA level, genes for VHW-1 and VHH-1 have a 97% homology, while at the protein level they have a 91% homology of amino acid sequences. Neither gene sequence showed homology to any other β-lactamases in the databases. The deduced proteins were found to be class A β-lactamases bearing low levels of homology (<50%) to other β-lactamases of the same class. The highest level of identity was obtained with β-lactamases from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, i.e., PSE-1, PSE-4, and CARB-3, and Vibrio cholerae CARB-6. Our study showed that both strains W3B and HB3 possess an endogenous plasmid of approximately 60 kb in size. However, Southern hybridization analysis employing blaVHW-1 as a gene probe demonstrated that the bla gene was not located in the plasmid. A total of nine ampicillin-resistant V. harveyi strains, including W3B and HB3, were examined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of NotI-digested genomic DNA. Despite a high level of intrastrain genetic diversity, the blaVHW-1 probe hybridized only to an 80- or 160-kb NotI genomic fragment in different isolates.

The farming of panaeid shrimp is a significant aquaculture activity in many Asian countries, like Thailand, Indonesia, and India (23). The industry is frequently plagued by bacterial infections, particularly vibriosis caused by luminous vibrios, such as Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio splendidus. V. harveyi is recognized as the main causative agent of luminous vibriosis (15, 16), which often results in mass mortality of the affected shrimp, hence leading to extensive farm losses (11). Consequently, antibiotics like streptomycin, erythromycin, and chloramphenicol are used to treat infections while oxytetracycline and penicillin are commonly used as prophylactic agents (32).

Luminous vibrios isolated from shrimp hatcheries on Java island, Indonesia, have demonstrated multiantibiotic resistance to antimicrobials like ampicillin, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and streptomycin (32). Therefore, it is likely that the excessive use of antibiotics has also contributed to increasing numbers of drug-resistant V. harveyi strains (1). On the other hand, antibiotic-resistant isolates of V. harveyi could also be isolated from pristine marine habitats, which might be an indication that the antibiotic-resistant determinants are already widely disseminated in nature. If this is the case, the use of antimicrobials in farming systems may not be responsible for the spread of bacterial resistance (35).

A number of mechanisms are known to operate in mediating bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., ampicillins and cephalosporins), but resistance predominantly results from the hydrolyzing activity of β-lactamases. Four molecular classes (classes A, B, C, and D) of β-lactamases are recognized, with classes A, C, and D having a serine residue at the active site of the enzyme (17). In many gram-negative bacteria, the structural gene for class A β-lactamases is frequently plasmid contained. However, chromosomal genes encoding class A β-lactamases have been described for Yersinia (26), Klebsiella (9), and Serratia (18) spp.

The genetic basis for β-lactam antibiotic resistance in V. harveyi has not been studied. This paper describes the cloning and sequence analysis of two novel chromosomally borne β-lactamase structural genes from two different environmental isolates of ampicillin-resistant V. harveyi cells. The deduced amino acid sequences of these β-lactamases were compared to other class A β-lactamases. The genomic locations and distribution of the β-lactamase genes in other V. harveyi isolates were also investigated.

(Part of this work was presented at the ASM Conference on Microbial Biodiversity, Chicago, Ill., 5 to 9 August 1999.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. V. harveyi strains were isolated from shrimp farms and coastal seawaters of Java island, Indonesia. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) media. Ampicillin-resistant (Ampr) V. harveyi strains were grown routinely in LB media containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source | Geographic location | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||||

| E. coli TOP10 | F−mcrA(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80 lac2 ΔM15 Δlac74 recA1 deoR araD139Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG) | Invitrogen | ||

| V. harveyi isolates | ||||

| W3B | Ampr | Seawater near shrimp hatchery | Besuki, northern coast of East Java | |

| E2 | Ampr | Shrimp egg | Besuki, East Java | |

| GCB | Ampr | Shrimp gut | Besuki, East Java | |

| P1B | Ampr | Shrimp larvae | Besuki, East Java | |

| M1 | Ampr | Mysis (prawn larval stage) | Besuki, East Java | 30 |

| M3.4L | Ampr | Mysis (prawn larval stage) | Labuhan, northern coast of West Java | |

| AP5 | Ampr | Seawater | Pacitan, southern coast of East Java | |

| AP6 | Ampr | Seawater | Pacitan, East Java | |

| HB3 | Ampr | Seawater | Pacitan, East Java | |

| Plasmids | ||||

| pCR 2.1-TOPO | PCR TOPO vector | Invitrogen | ||

| pAS900 | Kmr Amps; derivative of pCR 2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) cloning vector carrying an XmnI-ScaI deletion in ampicillin resistance gene | A. Suwanto (unpublished) | ||

| pVHA1 | pAS900 recombinant plasmid containing a 1.1-kb HindIII chromosomal fragment from W3B | This study | ||

| pVHA4 | pAS900 recombinant plasmid containing a 1.1-kb HindIII chromosomal fragment from HB3 | This study |

Antimicrobial agents and MIC determinations.

Susceptibility to antimicrobial agents was determined by MICs. The antibiotics used were ampicillin, penicillin, carbenicillin, amoxicillin, cephalothin, cefotaxime, chloramphenicol, oxytetracycline, erythromycin, and streptomycin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). MICs were determined by an agar dilution technique on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, England) with an inoculum of 104 CFU/spot. All plates were read after an 18-h incubation at 37°C. The MIC for imipenem was determined by the E-test method (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) following manufacturer's instructions.

Enzymes and chemicals.

All chemicals used were of the highest grade commercially available. All restriction enzymes used were purchased from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.) and used according to manufacturer's recommendations.

DNA cloning and analysis of recombinant plasmids.

Genomic DNA from V. harveyi HB3 and W3B was extracted by using phenol-chloroform (24). The DNA was digested with HindIII, and the resulting fragments were ligated into the HindIII site of the pAS900 vector. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.), and transformants were selected for ampicillin resistance. Recombinant plasmid DNA was prepared by alkaline lysis (24). T4 DNA ligase was purchased from New England Biolabs. Fragment sizes were estimated by comparison to the 1-kb DNA ladder (New England Biolabs) as the molecular size standard.

DNA sequencing.

The 1.1-kb HindIII fragment from pVHA1 and pVHA4 was sequenced on both strands by using the ABI Prism Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit and ABI cycle sequencer A373 (Applied Biosystems/Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). DNA sequencing was performed by using M13 forward and reverse primers. Later, internal sequencing primers were constructed from the available DNA sequences to complete the sequence walk. Sequencing primers were 18-mers chosen from the last 100 nucleotides read on the chromatograms. The oligonucleotides were synthesized by GENSET (Singapore Biotech. Pty., Ltd., Singapore).

DNA sequencing and protein analysis.

DNA sequence analysis was performed with DNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering Co. Ltd., San Bruno, Calif.). Database similarity searches for both the nucleotide sequences and deduced protein sequences were carried out at the National Center of Biotechnology Information website. Multiple sequence alignment of the deduced peptide sequence was carried out by using CLUSTALW over the Internet. A phylogenetic tree was also constructed by using the Treecon for Windows version 1.3b software package (33). Deduced amino acid sequences for pVHA1 and pVHA4 were compared to 13 other class A β-lactamases: PSE-1, PSE-4, CARB-3 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3, 13, 14), CTX-M-5, CTX-M-3 from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (4; M. Gazouli, unpublished data), AER-1 from Aeromonas hydrophila (25), CARB-6 from Vibrio cholerae (6), ROB-1 from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (5), Bacillus thuringiensis β-lactamase (36), Streptomyces fradiae Y59 β-lactamase (20), OXY-2 from Klebsiella oxytoca (8), Serratia marcescens S5 β-lactamase (20), and β-lactamase from Proteus mirabilis N-29 (31). The identification of signal peptides was carried out with the program SignalP V1.1 at the Center for Biological Sequence Analysis over the Internet (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) (19).

Preparation of genomic DNA gel inserts for PFGE.

V. harveyi strains W3B and HB3 were grown overnight at 30°C in 10 ml of Luria-Bertani broth. Preparation of genomic DNA inserts in low-melting-point agarose Seaplaque (FMC Bioproducts) and restriction digestion of the inserts were performed as previously described (27). Restriction digestion of the inserts is briefly described as follows. Each gel slice was incubated with 200 μl of the appropriate 1× restriction enzyme buffer supplemented with 100 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml for at least 15 min on ice. The buffer was then removed, and fresh buffer was added together with 20 U of restriction enzyme. This was placed for another 15 min on ice before being left to incubate at 37°C for 4 h. The restriction enzyme NotI was used for digestion of inserts. The DNA fragments were electrophoresed on a 1% Seakem GTG (FMC Bioproducts) gel in a 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer using a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field device (CHEF-DR III; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Running conditions were 6 V cm−1 for 20 h with a ramping time of 20 to 60 s. AseI-digested genomic DNA from Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 was used as the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) molecular size marker (27).

Preparation of large endogenous plasmid for PFGE.

Plasmids were extracted from two isolates, HB3 and W3B, by using a modification of the alkaline lysis method in which phenol extraction was performed with neutralized phenol equilibrated in 3% sodium chloride without chloroform and isoamyl alcohol (28). The dried plasmid pellet was resuspended in an appropriate volume of sterile water for restriction digestion. An equal volume of 1% low-melting-point agarose was added to the digested samples before loading. DNA fragments were electrophoresed in a 1.2% Seakem GTG agarose gel. The PFGE running conditions were 6 V cm−1 for 12 h with a ramping time of 1 to 8 s.

Southern blotting and hybridization for PFGE gels.

The procedure for Southern blotting was according to the instructions given in the ECL Nonradioactive Detection Kit (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England) except that the 15 min depurination was carried out twice. DNA fragments of PFGE gels were capillary blotted onto nylon hybridization membranes (Hybond-N+; Amersham) and fixed by baking at 80°C for 2 h. The hybridization probe was the 1.1-kb HindIII-HindIII fragment from pVHA1. The fragment was excised from Seaplaque (FMC Bioproducts) low-melting-point gel and purified from the gel by using GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Uppsala, Sweden). Hybridization was performed overnight with high-stringency conditions as described by the manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences for blaVHW-1 and blaVHH-1 have been deposited into the GenBank database under the accession numbers AF 217648 and AF 217649, respectively.

RESULTS

Sequence analyses of blaVHW-1, blaVHH-1, and their deduced amino acid sequences.

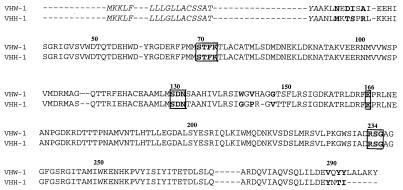

The 1.1-kb DNA inserts present on pVHA1 and pVHA4 were sequenced on both strands. Analysis of the pVHA1 insert revealed the presence of an open reading frame (ORF) of 870 bp which encoded a putative 290-amino-acid (290-aa) preprotein (designated VHW-1). Similarly, the cloned insert in pVH4 was shown to have an ORF of 849 bp with a predicted 283-aa-long preprotein (designated VHH-1). A 19-aa signal peptide was deduced for both VHW-1 and VHH-1 (Fig. 1). Four important structural features found conserved in class A β-lactamases were present in the deduced amino acid sequences of VHW-1 and VHH-1, which included an STFK active site tetrad at position 70 to 73 according to Ambler's standard numbering of class A β-lactamases (2). This Ser-X-X-Lys tetrad is characteristic of penicillin binding proteins (PBPs) and serine β-lactamases (10). An SDN loop characteristic of class A β-lactamases (10) was located at position 130 to 132 on VHW-1 and VHH-1 as well as the unique Glu residue at position 166. Lastly, an RSG triad was established at position 234 to 236 on both β-lactamases (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of VHH-1 and VHW-1. Ambler's standard numbering of β-lactamases was used (2). Dashes indicate gaps that were used to maximize the alignment. Unconserved residues between the two sequences are indicated in bold. Conserved amino acid regions important for catalytic function of β-lactamases are boxed. A 19-aa signal peptide is indicated in italics.

Sequence homology with other β-lactamases.

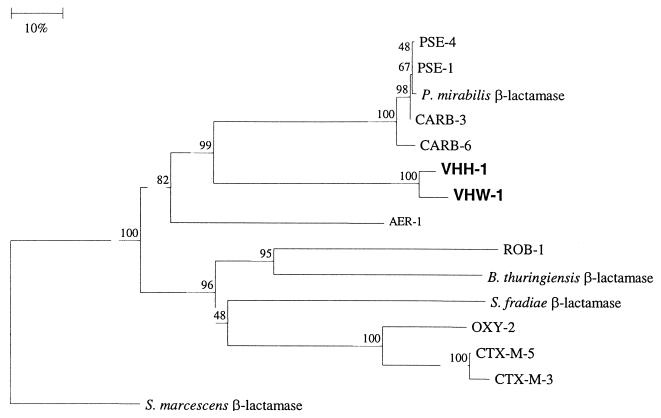

Database searches of VHW-1 and VHH-1 β-lactamase genes generated no homology with any other class A β-lactamases in the databases, but they have a 97% homology between themselves. The deduced amino acid sequence of both VHW-1 and VHH-1 had less than 50% identity with other class A β-lactamases. VHW-1 had the highest level of identity (45%) with P. aeruginosa β-lactamases PSE-4 and CARB-3 and V. cholerae CARB-6. VHH-1 had the highest percentage identity with PSE-1, PSE-4, CARB-3, and CARB-6, at 46% (Table 2). The phylogenetic tree constructed for VHW-1 and VHH-1 shows that only these two enzymes clustered together and had a 91% amino acid sequence identity. Therefore, VHW-1 and VHH-1 β-lactamases are novel and distinctly different from the other known β-lactamases (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Amino acid identity of VHW-1 and VHH-1 with several related class A β-lactamases

| β-Lactamase | % Identity

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSE-1 | PSE-4 | CARB-3 | CARB-6 | AER-1 | VHW-1 | |

| PSE-4 | 99 | |||||

| CARB-3 | 99 | 99 | ||||

| CARB-6 | 94 | 94 | 43 | |||

| AER-1 | 41 | 43 | 43 | 42 | ||

| VHW-1 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 40 | |

| VHH-1 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 41 | 91 |

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of 15 class A β-lactamases. Branch lengths are drawn to scale and proportional to the number of amino acid changes. The bootstrap values are indicated at each node. The β-lactamases used for comparison were PSE-1, PSE-4, and CARB-3 from P. aeruginosa (3, 13, 14), CTX-M-5, CTX-M-3 from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (4; Gazouli, unpublished), AER-1 from A. hydrophila (25), CARB-6 from V. cholerae (6), ROB-1 from A. pleuropneumoniae (5), B. thuringiensis β-lactamase (36), S. fradiae Y59 β-lactamase (20), OXY-2 from K. oxytoca (8), S. marcescens S5 β-lactamase (20), and β-lactamase from P. mirabilis N-29 (31).

Antibiotic susceptibility.

E. coli TOP10 cells harboring recombinant plasmids pVHA1 and pVHA4 had elevated levels of resistance to penicillins compared to those of the host strain alone, indicating that the cloned insert did contain the bla gene which conferred β-lactam resistance (Table 3). MICs for imipenem, cephalothin, and cefotaxime were similar to those of TOP10 cells alone, thus revealing there was no resistance to these antibiotics. All the environmental isolates of V. harveyi showed a fairly high level of resistance to penicillins (Table 3). All the strains were, however, susceptible to streptomycin, erythromycin, oxytetracycline, and chloramphenicol with the exception of strain M3.4L, which had a significant level of resistance to oxytetracycline (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

MICs of β-lactams for E. coli TOP10 cells harboring recombinant plasmids pVHA-1 and pVHA-4 and environmental isolates of V. harveyi

| β-Lactam | MIC (μg/ml) of drug:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli

|

V. harveyi

|

|||||||||||

| TOP10 | TOP10(pVHA1) | TOP10(pVHA4) | W3B | HB3 | M1 | E2 | GCB | P1B | AP5 | AP6 | M3.4L | |

| Ampicillin | 1 | 256 | 256 | 128 | 256 | 64 | 32 | >512 | 256 | >512 | 256 | 256 |

| Penicillin | 0.12 | >512 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | >512 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 |

| Carbenicillin | 4 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 128 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 |

| Amoxicillin | 8 | >512 | >512 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| Oxacillin | 128 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | 128 | 128 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 |

| Imipenem | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125 | —a | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cephalothin | 8 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cefotaxime | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

—, not determined.

TABLE 4.

MICs of antibiotics for environmental strains of V. harveyi

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) for V. harveyi strains

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB3 | W3B | M1 | E2 | GCB | P1B | AP5 | AP6 | M3.4L | |

| Streptomycin | 4 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 8 |

| Erythromycin | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Oxytetracycline | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 128 |

| Chloramphenicol | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

DNA profiling analysis employing PFGE.

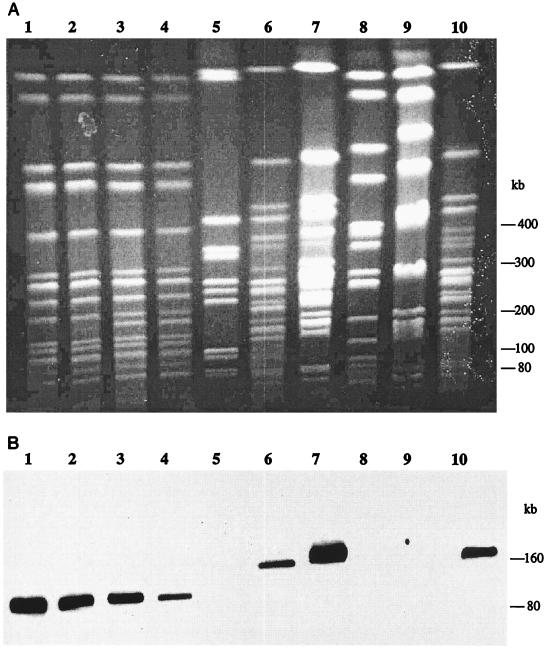

PFGE was employed to reveal the genetic diversity of V. harveyi isolated from various geographic locations. Six different restriction patterns or schizotypes (29) were obtained when digested with NotI (Fig. 3). This result indicated a high level of genetic diversity among the isolates. Strain W3B is genetically different from strain HB3, as shown from the PFGE data (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 4). Strains AP5 and HB3, both isolated from the southern coast of East Java, demonstrated identical NotI schizotypes or distribution of restriction fragments (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4). The PFGE profile of strain W3B was found to be identical to that of strain GCB (both were isolated from the northern coast of East Java) (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 2), and AP6 was identical to P1B (Fig. 3, lanes 6 and 7). The remaining strains M3.4L, E2, and M1 had unique NotI restriction patterns.

FIG. 3.

(A) PFGE of NotI-digested DNA from nine environmental isolates of V. harveyi. (B) Southern hybridization analysis of DNA. The probe used was the 1.1-kb HindIII fragment containing blaVHW-1. Lanes: 1, W3B; 2, GCB; 3, AP5; 4, HB3; 5, R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 DNA digested with AseI (molecular size standard); 6, AP6; 7, P1B; 8, M1; 9, E2; 10, M3.4L.

Distribution of blaVHW-1 gene in other V. harveyi isolates.

The 1.1-kb HindIII fragment from the recombinant plasmid pVHA1 containing the blaVHW-1 gene was used to probe against NotI-digested DNA from eight other isolates (Fig. 3). Hybridization occurred at the 80-kb NotI chromosomal band in strains W3B, AP5, GCB, and HB3 and the 160-kb NotI chromosomal band in strains P1B, AP6, and M3.4L. No hybridization was detected for strains M1 and E2, indicating the absence of blaVHW-1 or a homologue in these strains. Using PFGE, a 60-kb plasmid with an identical plasmid profile was detected for strains HB3 and W3B (data not shown). Southern blot analysis employing blaVHW-1 as a probe demonstrated that the bla gene was not located in this large endogenous plasmid.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have cloned novel bla genes from two environmental isolates of V. harveyi. The blaVHW-1 gene was derived from strain W3B isolated from seawater around a shrimp hatchery in the northern coast of East Java while blaVHH-1 was isolated from strain HB3, a pristine seawater isolate from the southern coast of East Java. Sequence analysis of the bla genes demonstrated that they did not have homology to any other β-lactamase genes. At the amino acid level, VHW-1 and VHH-1 possess low levels of homology to other class A β-lactamases, and regions which are strongly conserved are implicated in enzyme catalysis. These results reflect the extensive diversity of β-lactamase genes.

Southern blot analysis using blaVHW-1 as a probe revealed that the β-lactamase was chromosomally encoded and apparently present as a single copy. The gene blaVHW-1 and its highly homologous counterpart (blaVHH-1) was also present in other ampicillin-resistant strains of V. harveyi, suggesting that this bla gene is widely disseminated. Since the gene is also present in isolates obtained from the pristine marine water environment (strains HB3, AP5, and AP6), this bla gene is likely not to have been a consequence of antibiotic selection pressure imposed by shrimp farming. In the marine habitat, cyanobacteria are known to naturally excrete antibiotics and possibly β-lactams (22). Hence, β-lactamase production in V. harveyi cells might have been maintained in response to natural environmental selection.

Southern hybridization and PFGE analysis of several other ampicillin-resistant V. harveyi isolates indicated that blaVHW-1- like genes are located on either 80- or 160-kb NotI genomic fragments. These results suggests that the gene is present in a conserved segment surrounded by a variable genetic environment as demonstrated by the high genetic diversity of the isolates.

Resistance to β-lactams is often the result of β-lactamases that inactivate the antibiotics. In addition to class A β-lactamases, three other molecular classes of β-lactamases (B, C, and D) are recognized. The blaVHW-1 gene probe failed to hybridize to two ampicillin-resistant V. harveyi strains (M1 and E2); therefore, the ampicillin-resistant determinants of strains HB3 and W3B might not account entirely for β-lactam resistance in some other strains. It seems likely that β-lactamases belonging to the other molecular classes, such as B, C, or D, are also responsible for ampicillin resistance. Some gram-negative bacteria acquire resistance by changing the permeability of outer membrane porin channels, consequently leading to reduced drug influx into the bacterial cell. In addition, PBP-mediated resistance arises when PBPs failed to bind or exhibited reduced affinity to β-lactams (7). It is plausible that the latter two mechanisms are also contributing to β-lactam resistance in ampicillin-resistant strains.

A single, large 60-kb plasmid could be isolated from strain W3B or HB3. Although no hybridization to the blaVHW-1 probe could be detected, the plasmid might encode virulence factors, resistance determinants to other classes of antibiotics or factors required for survival and fitness in their natural environment. We are currently characterizing the plasmid and determining its ubiquity in V. harveyi isolates.

Class A β-lactamases of gram-negative bacteria can be divided into two subgroups (26). The first subgroup is the chromosomal branch and the second is the transposon branch. Members of each subgroup share distinctive residues. Nine out of 11 bases of the transposon branch are conserved in VHW-1 and VHH-1, suggesting that it is possible that bla genes might have been carried in a transposon or integron before being integrated into the chromosome. Often, antibiotic resistance genes encoding resistance to a variety of antibiotics, such as β-lactams, chloramphenicol, and aminoglycosides, are found integrated in a site-specific manner in a mobile gene cassette or integron (21). Both the 5′ and the 3′ ends of integrons are conserved. The 5′ conserved region encodes an integrase while the 3′ segment often carries qacEΔ1 and sulI genes, which determine resistance to ethidium bromide and quaternary ammonium compounds and to sulfonamides, respectively. Another conserved feature is the presence of an imperfect inverted repeat consensus of 59 bp located downstream of the inserted resistance genes. Integrons are found commonly in gram-negative pathogenic bacteria, especially from the Enterobacteriaceae and the pseudomonads. These mobile genetic elements are capable of interspecies transfer. The amino acid sequence homology of VHW-1 and VHH-1 indicates that the highest levels of homology are obtained with β-lactamases from Pseudomonas, i.e., PSE-1, PSE-4, and CARB-3, and a β-lactamase from V. cholerae CARB-6. These PSE- and CARB-type enzymes have structural genes that are part of a transposon or an integron (3). Currently, the lack of flanking upstream and downstream sequences of the blaVHW-1 and blaVHH-1 genes makes it difficult to ascertain their genetic context and whether the genes are integron or transposon borne.

A large, conjugative, chromosomally integrating transposon named the SXT element has been discovered in V. cholerae O139 (34). This 62-kb element is not only self-transmissible but can also be transferred into E. coli strains and its integration into the host genome is site specific. The transposon encodes multiantibiotic resistance against streptomycin, furazolidone, and trimethoprim. It can be envisaged that such conjugative elements might also exist in V. harveyi organisms, and the presence of the bla gene on either a transposon or an integron might help to explain the wide dissemination of the ampicillin resistance gene as well as the specific localization of the β-lactamase genes on either the 60- or 160-kb NotI fragment in various ampicillin-resistant isolates.

Future work will involve determining the flanking sequences of the β-lactamase gene, mechanisms of transfer, and distribution of ampicillin resistance, as well as the biochemical characterization of the protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National University of Singapore Academic Research grant RP3991315, to C. L. Poh and the International Foundation for Science, Sweden, grant A/2207-2 to A. Suwanto.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham T J, Manley R, Palaniappan R, Dhevendaran K. Pathogenicity and antibiotic sensitivity of luminous Vibrio harveyi isolated from diseased penaeid shrimp. J Aquacult Trop. 1997;12:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambler R P. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980;289:321–331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boissinot M, Levesque R C. Nucleotide sequence of the PSE-4 carbenicillinase gene and correlations with the Staphylococcus aureus PC-1 β-lactamase crystal structure. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1225–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford P A, Yang Y, Sahm D, Grope I, Gardovska D, Storch G. CTX-M-5, a novel cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from an outbreak of Salmonella typhimurium in Latvia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1980–1984. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Y F, Shi J, Shin S J, Lein D H. Sequence analysis of the ROB-1 β-lactamase gene from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Vet Microbiol. 1992;32:319–325. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90154-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choury D, Aubert G, Szajnert M F, Azibi K, Delpech M, Paul G. Characterization and nucleotide sequence of CARB-6, a new carbenicillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from Vibrio cholerae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:297–301. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dever L A, Dermody T S. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:886–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farzaneh S, Peduzzi J, Sofer L, Reynaud A, Barthélémy M, Labia R. Characterization and amino acid sequence of the OXY-2 group β-lactamase of pI 5.7 isolated from aztreonam-resistant Klebsiella oxytoca strain HB60. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:789–795. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haeggman S, Löfdahl S, Burman L G. An allelic variant of the chromosomal gene for class A β-lactamase K2, specific for Klebsiella pneumoniae, is the ancestor of SHV-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2705–2709. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joris B, Ledent P, Dideberg O, Fonzé E, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Kelly J A, Ghuysen J M, Frère J M. Comparison of the sequences of class A β-lactamases and of the secondary structure elements of penicillin-recognizing proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2294–2301. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karunasagar I, Pai R, Malathi G R, Karunasagar I. Mass mortality of Panaeus monodon larvae due to antibiotic-resistant Vibrio harveyi infection. Aquaculture. 1994;128:203–209. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurai S, Urabe H, Ogawara H. Cloning, sequencing, and site-directed mutagenesis of β-lactamase gene from Streptomyces fradiae Y59. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:260–263. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labia R, Guionie M, Barthélémy M. Properties of three carbenicillin-hydrolysing β-lactamases (CARB) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of a new enzyme. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981;7:49–56. doi: 10.1093/jac/7.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lachapelle J, Dufresnes J, Levesque R C. Characterization of the blaCARB-3 gene encoding the carbenicillinase-3 β-lactamase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1991;102:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90530-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavilla-Pitogo C R, Leaño E M, Paner M G. Mortalities of pond-cultured juvenile shrimp, Panaeus monodon, associated with dominance of luminescent vibrios in the rearing environment. Aquaculture. 1998;164:337–349. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavilla-Pitogo C R, Barticados M C L, Cruz-Lacierda E R, de la Peña L D. Occurrence of luminous bacterial disease of Panaeus monodon larvae in the Philippines. Aquaculture. 1990;91:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massova I, Mobashery S. Kinship and diversification of bacterial penicillin-binding proteins and β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1–17. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naas T, Vandel L, Sougakoff W, Livermore D M, Nordman P. Cloning and sequence analysis of the gene for a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase, Sme-1, from Serratia marcescens S6. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1262–1270. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.6.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, Heijne G V. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perilli M, Felici A, Franceschini N, De Santis A, Pagani L, Luzzaro F, Oratore A, Rossolini G M, Knox J R, Amicosante G. Characterization of a new TEM-derived β-lactamase produced in a Serratia marcescens strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2374–2382. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reccchia G D, Hall R M. Origins of the mobile gene cassettes found in integrons. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:389–394. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rheinheimer G. Aquatic microbiology. Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruangpan L. Luminous bacteria associated with shrimp mortality. In: Flegel T W, editor. Advances in shrimp biotechnology. Bangkok, Thailand: National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology; 1998. pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanschagrin F, Bejaoui N, Levesque R C. Structure of CARB-4 and AER-1 carbenicillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1966–1972. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seoane A, Garcia Lobo J M. Nucleotide sequence of a new class A β-lactamase gene from the chromosome of Yersinia enterocolitica: implications for the evolution of class A β-lactamases. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;228:215–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00282468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suwanto A, Kaplan S. Physical and genetic mapping of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 genome: genome size, fragment identification, and gene localization. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5840–5849. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5840-5849.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suwanto A, Kaplan S. A self-transmissible, narrow-host-range endogenous plasmid of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: physical structure, incompatibility determinants, origin of replication, and transfer functions. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1124–1134. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1124-1134.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suwanto A, Kaplan S. Chromosome transfer in Rhodobacter sphaeroides: Hfr formation and genetic evidence for two unique circular chromosomes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1135–1145. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1135-1145.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suwanto A, Yuhana M, Herawaty E, Angka S L. Genetic diversity of luminous Vibrio isolated from shrimp larvae. In: Flegel T W, editor. Advances in shrimp biotechnology. Bangkok, Thailand: National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology; 1998. pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi I, Tsukamoto K, Harada M, Sawai T. Carbenicillin-hydrolyzing penicillinases of Proteus mirabilis and the PSE-type penicillinase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Immunol. 1983;27:995–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1983.tb02934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tjahjadi M R, Angka S L, Suwanto A. Isolation and evaluation of marine bacteria for biocontrol of luminous bacterial disease in tiger shrimp larvae (Panaeus monodon, Fab.) Asia Pac J Mol Biol Biotechnol. 1994;2:347–352. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van de peer Y. Treecon for Windows version 1.3b software package. Antwerp, Belgium: Department of Biochemistry, University of Antwerp; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waldor M K, Tschäpe H, Mekalanos J J. A new type of conjugative transposon encodes resistance to sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and streptomycin in Vibrio cholerae O139. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4157–4165. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4157-4165.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witte W. Impact of antibiotic use in animal feeding on resistance of bacterial pathogens in humans. In: Chadwick D J, Goode J, editors. Antibiotic resistance: origins, evolution, selection and spread. Ciba Foundation Symposium 207. Chichester, N.Y: Wiley; 1997. pp. 61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang M Y, Lovgren A. Cloning and sequencing of a β-lactamase-encoding gene from the insect pathogen Bacillus thuringiensis. Gene. 1995;158:83–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00089-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]