Abstract

Background

More than 2 billion people are thought to be living with some form of vision impairment worldwide. Yet relatively little is known about the wider impacts of vision loss on individual health and well-being, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This study estimated the associations between all-cause vision impairment and self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression among older adults in Kogi State, Nigeria.

Methods

Individual eyes were examined according to the standard Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness methodology, and anxiety and depression were assessed using the Washington Group Short Set on Functioning–Enhanced. The associations were estimated using multivariable logistic regression models, adding two- and three-way interaction terms to test whether these differed for gender subgroups and with age.

Results

Overall, symptoms of either anxiety or depression, or both, were worse among people with severe visual impairment or blindness compared with those with no impairment (OR=2.72, 95% CI 1.86 to 3.99). Higher levels of anxiety and/or depression were observed among men with severe visual impairment and blindness compared with women, and this gender gap appeared to widen as people got older.

Conclusions

These findings suggest a substantial mental health burden among people with vision impairment in LMICs, particularly older men, underscoring the importance of targeted policies and programmes addressing the preventable causes of vision impairment and blindness.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, disease burden, Nigeria, older adults, vision impairment

Introduction

According to the WHO, >2 billion people are living with some form of vision impairment globally.1 The majority live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with impairments that could have been prevented or have yet to be addressed. Over the next 30 y this number is expected to rise as a result of population ageing and growth.2

The recent Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health concluded that vision impairment has wide ranging impacts on individual health and well-being.3 It highlighted the findings of a systematic review that showed the hazard for all-cause mortality was higher in people with vision impairment compared with those with normal vision or only mild vision impairment.4 Furthermore, the magnitude of this effect increased with the severity of vision loss. Another review underscored the link between vision impairment, eye diseases and quality of life, revealing that 75% of studies of ophthalmic interventions found evidence of improved quality of life.5

The causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between vision impairment and broader health are complex, but three main pathways can be identified: (1) eye conditions and other diseases share common risk factors; (2) some health conditions can lead to vision impairment; and (3) vision impairment can cause or exacerbate other health conditions.3

Evidence for the relationship between vision impairment and mental health is also increasing.6 Two recent meta-analyses of studies of patients receiving eye care services found that the pooled prevalence of depression in patients with vision problems was as high as 25%; the prevalence did not vary by severity of vision impairment but was found in patients visiting both eye clinics and rehabilitation centres.7,8 In China, results from a 16-y longitudinal study also showed unoperated cataract was associated with an increased risk of developing depression over time, and was similar among both males and females, and older and younger patients.9 However, the relationship between vision impairment and mental health in LMICs, and the effect of gender and age on this relationship, is not well explored.

In Nigeria, vision impairment and blindness is a significant public health concern. Blindness is defined as presenting visual acuity (PVA; i.e. with whatever refractive correction the person normally uses) <3/60; severe visual impairment (SVI) is defined as PVA<6/60 but ≥3/60; and moderate visual impairment (MVI) is defined as PVA<6/18 but ≥6/18.10 The National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey conducted in 2005–2007 found that 4.2% of people aged >40 y were blind and 11.5% had MVI to SVI.11 In terms of the burden of mental ill health, the WHO Mental Health Survey published in 2009 estimated that the lifetime prevalence of any mental health disorder in the Nigerian population was 12%, while the prevalence of anxiety disorders was 6.5% and 3% for mood disorders, including depression.12 In 2019, a study conducted in Imo State in Nigeria found that increased levels of vision impairment were associated with a 19% reduction in quality of life in the psychological domain.13 The same study found that increased age, duration of visual impairment, a history of poor near vision, and having a primary diagnosis of cataract or glaucoma compared with unaddressed refractive error, were found to be significantly associated with lower quality of life scores. Overall, however, evidence from LMICs, particularly African settings, is scarce.

This study aimed to respond to this evidence gap, examining the associations between all-cause vision impairment and self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression among people aged ≥50 y in Kogi State in Nigeria. In addition, it tested whether associations differed for gender subgroups and by age.

Methods

Study design and sampling

Data were collected as part of a Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB), which is a cross-sectional, population-based survey of vision impairment conducted among adults aged ≥50 y.14 Data were collected from October 2019 to March 2020. The study population was therefore people aged ≥50 y who were ordinarily resident in Kogi State, which is located in the Nigerian Middle Belt and has an estimated total population of about 4.5 million.

The survey adopted a two-stage cluster sampling approach. First, a complete list of villages was obtained from the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics (based on the 2006 census and 2016 projections) and villages were selected at random using probability proportionate to size. Second, each village was visited to identify village boundaries. If the village population was large, a map was developed with the village leader and the village was divided into segments. In this case, ‘large’ was around 500 inhabitants as it assumed that around 10% of the population is aged ≥50 y, and this size of village would therefore include the 50 eligible participants required for enrolment. In larger villages, where the population exceeded 500 total inhabitants, a segment was then selected at random and that segment was surveyed. In small villages where fewer than 50 people aged ≥50 y could be enrolled, the team travelled to the nearest neighbouring village to continue enrolment.

According to calculations made using the parameters—an expected prevalence of blindness of 3.75% (as per the estimate of blindness reported for the North Central geopolitical zone, in which Kogi lies, in the Nigeria National Blindness survey11); 20% precision; 5% alpha; 10% non-response; and a design effect of 1.5—an estimated 4150 people were required for the RAAB survey.

Data collection and tools

Five study teams comprising an ophthalmologist and an ophthalmic nurse were trained on the study protocol and procedures by a certified RAAB trainer. The training included 3 d of training and practice on sampling and ethical procedures, visual assessment, disability and wealth questions, and using the mobile data collection devices. A fourth day was spent in a local outpatient department where an interobserver variation (IOV) test was conducted and a fifth day was spent conducting further practice in a local community. The first IOV test resulted in several scores falling short of the minimum 60% agreement threshold, and so the test was repeated the following week following some additional practice and training. Two teams continued to fall short of the required standard, and so the study proceeded with the three teams that consistently met and surpassed the 60% agreement threshold. Data collection commenced in October 2019 but was paused from November to February 2020 due to local elections and holiday periods. Refresher training was conducted in early March 2020 and data collection was completed by the end of March 2020.

Individual eyes were examined according to the standard RAAB methodology.14 The eye examination was conducted by the trained ophthalmic team and included: (1) measurement of PVA for each eye (all participants); (2) measurement of pinhole visual acuity for each eye with PVA<6/18; (3) lens examination of each eye with a torch in a darkened room (all participants); (4) posterior-segment examination with a torch of each eye with PVA<6/18 where the principal cause could not be attributed to refractive error, cataract or corneal scarring; (5) assessment of the major cause of vision impairment for each eye with PVA<6/18 and in people where both eyes had PVA<6/18 and the causes were not the same; (6) questions regarding cataract surgery (for participants operated for cataract [pseudophakia]); and (7) questions regarding why cataract surgery had not taken place (for participants with operable cataract).

Anxiety and depression (dependent variable)

Self-reported anxiety and depression was measured using questions from the Washington Group Short Set on Functioning–Enhanced (WG-SS Enhanced).15 The WG-SS Enhanced is designed to collect information on difficulties a person may have undertaking basic functioning activities in eight domains: seeing, hearing, walking or climbing stairs, remembering or concentrating, self-care, communication (expressive and receptive), upper body activities and affect (depression and anxiety).

Respondents were asked (1) how often they felt worried, nervous or anxious; (2) how often they felt depressed; and (3) about the severity of their feelings. The binary dependent variable used in this analysis measured moderate to severe anxiety and/or depression, which was defined as self-reported symptoms that were either daily or weekly and were ‘a lot’ or ‘in between (a lot and a little)’ in severity. It equalled one if respondents reported symptoms of either anxiety or depression or both, and zero otherwise.

Vision impairment (independent variable)

Categories of vision impairment were based on presenting vision in the better-seeing eye: (1) MVI (PVA≥6/60 and <6/18); (2) SVI (PVA≥3/60 and <6/60); and (3) blindness (PVA<3/60). To maximise sample size, these categories were used to construct the following independent variables: MVI, which included people who met the definition of moderate visual acuity or worse; SVI, which included people meeting the severe visual acuity or blindness definitions; and a final variable, which used the definition of blindness only.

Other covariates

Additional disability was defined as having at least some difficulties undertaking basic hearing, mobility, communication, cognition or self-care activities in the WG-SS Enhanced. Relative household wealth was measured using the Nigeria Equity Tool, a country-specific asset-based index that has been used widely to evaluate differences between social and economic groups.16 Depending on the ownership of items from a standardised list of assets, households were categorised into one of five quintiles, with the poorest and often most marginalised in the bottom quintile and the wealthiest in the top quintile. The cut-off points are determined using data from the most recent Demographic and Health Survey. If a studied population is similar in their wealth profile to the national population, one would expect 20% of the sample be in each of the five quintiles.

Statistical analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression to analyse the association between vision impairment and self-reported symptoms of either anxiety or depression, or both.

Models were adjusted for individual (gender, age and additional disabilities) and household level (wealth) confounders. Cluster robust standard errors were specified to account for complex survey design. Subgroup analyses examined whether the association between anxiety, depression and vision impairment differed for gender subgroups and with age by adding two-way (vision impairment with gender) and three-way interaction terms (vision impairment with gender with age) to the adjusted regression models. Wald tests were used to determine statistical significance. Stored results from these fitted models were then used to calculate average adjusted probabilities (AAPs) and average marginal effects (AMEs). All analysis was conducted using Stata software version 16 (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Results

Characteristics of the sample

A total of 3926 individuals aged ≥50 y participated in the survey, a response rate of 94.6%. Overall, 12.5% reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety. Symptoms of depression were reported by 7.4%, and 14.8% reported symptoms of either anxiety or depression or both. Sample prevalence in male and female subgroups was similar (Table 1). In terms of vision impairment, 13.6% of respondents had MVI or worse (PVA<6/18); 5.3% had SVI or blindness (PVA<6/60) and 3.4% were blind (PVA<3/60). Vision impairment was slightly higher among men compared with women, although tests indicated differences were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Sample prevalence of anxiety, depression and vision impairment

| Total sample (n=3926) | Male (n=1643) | Female (n=2283) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | |||

| Anxiety | |||

| No | 87.5 (3436) | 87.3 (1435) | 87.6 (2001) |

| Yes | 12.5 (490) | 12.7 (208) | 12.4 (282) |

| Depression | |||

| No | 92.6 (3634) | 92.9 (1526) | 92.3 (2108) |

| Yes | 7.4 (292) | 7.1 (117) | 7.7 (175) |

| Anxiety and/or depression | |||

| No | 85.2 (3346) | 85.3 (1402) | 85.1 (1944) |

| Yes | 14.8 (580) | 14.7 (241) | 14.9 (339) |

| MVI (PVA<6/18) | |||

| No | 86.4 (3391) | 85.5 (1404) | 87.0 (1987) |

| Yes | 13.6 (535) | 14.5 (239) | 13.0 (296) |

| SVI (PVA<6/60) | |||

| No | 94.7 (3717) | 94.1 (1546) | 95.1 (2171) |

| Yes | 5.3 (209) | 5.9 (97) | 4.9 (112) |

| Blind (PVA<3/60) | |||

| No | 96.6 (3794) | 96.1 (1579) | 97.0 (2215) |

| Yes | 3.4 (132) | 3.9 (64) | 3.0 (68) |

Fifty-eight percent were women and two-thirds were aged 50–69 y. Participants lived in households that were relatively poorer compared with the national average, with 27.5% of households belonging in the lowest wealth quintile. Also, 5.4% of participants had additional disabilities (Table 2). Statistically significant differences between the group with vision impairment—measured as MVI or worse (PVA<6/18)—and the group with no vision impairment were observed by age, household wealth and additional disabilities. Specifically, the group with vision impairment were on average older, poorer and more likely to have additional disabilities compared with the group with no vision impairment.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of sample

| Total sample (n=3926) | No vision impairment (n=3391) | Vision impairment1 (n=535) | p-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 41.9 (1643) | 41.4 (1404) | 44.7 (239) | - |

| Female | 58.1 (2283) | 58.6 (1987) | 55.3 (296) | 0.154 |

| Age (y) | ||||

| 50–59 | 46.8 (1838) | 51.6 (1748) | 16.8 (90) | - |

| 60–69 | 28.9 (1136) | 29.6 (1004) | 24.7 (132) | - |

| 70–79 | 14.5 (571) | 13.4 (455) | 21.7 (116) | - |

| ≥80 | 9.7 (381) | 5.4 (184) | 36.8 (197) | <0.001 |

| Wealth | ||||

| 1st quintile | 27.5 (1078) | 27.0 (916) | 30.3 (162) | - |

| 2nd quintile | 16.2 (636) | 16.0 (542) | 17.6 (94) | - |

| 3rd quintile | 20.4 (801) | 20.1 (683) | 22.1 (118) | - |

| 4th quintile | 20.9 (820) | 21.1 (717) | 19.3 (103) | - |

| 5th quintile | 15.1 (591) | 15.7 (533) | 10.8 (58) | 0.022 |

| Disability3 | ||||

| No | 94.6 (3714) | 97.2 (3297) | 77.9 (417) | - |

| Yes | 5.4 (212) | 2.8 (94) | 22.1 (118) | <0.001 |

MVI (PVA<6/18).

p-values are based on Pearson's χ2 test.

Additional disabilities (hearing, walking/climbing, remembering/concentrating, upper body, communication).

Associations between vision impairment and anxiety and/or depression

Results from multivariable logistic regression models showed that the likelihood of reported symptoms of either anxiety or depression or both was higher in the group of people with vision impairment compared with those with no impairment (Table 3). The odds that individuals with MVI or worse experienced symptoms of anxiety and/or depression were twice as high as individuals with no vision impairment, after adjusting for potential confounding from gender, age, additional disabilities and household wealth (OR=1.99, 95% CI 1.48 to 2.70, p<0.001). For people with SVI or worse, the odds of anxiety and/or depression were almost threefold higher than for people with no vision impairment (OR=2.72, 95% CI 1.86 to 3.99, p<0.001). Among people who were blind the odds were 3.97-fold higher (OR=3.97, 95% CI 2.56 to 6.21, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Results from multivariable logistic regression models estimating the association between all-cause vision impairment and self-reported anxiety and/or depression

| MVI (PVA<6/18) | SVI (PVA<6/60) | Blind (PVA<3/60) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Anxiety/depression | |||||||||

| No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 1.999 | 1.48 to 2.70 | <0.001 | 2.723 | 1.86 to 3.99 | <0.001 | 3.973 | 2.54 to 6.21 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 1.042 | 0.84 to 1.30 | 0.713 | 1.047 | 0.84 to 1.30 | 0.677 | 1.052 | 0.85 to 1.31 | 0.645 |

| Age (y) | |||||||||

| 50–59 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 60–69 | 0.851 | 0.67 to 1.09 | 0.199 | 0.866 | 0.68 to 1.10 | 0.237 | 0.874 | 0.69 to 1.11 | 0.269 |

| 70–79 | 0.878 | 0.57 to 1.36 | 0.560 | 0.931 | 0.61 to 1.42 | 0.741 | 0.957 | 0.63 to 1.45 | 0.838 |

| ≥80 | 0.929 | 0.59 to 1.46 | 0.750 | 1.037 | 0.67 to 1.61 | 0.872 | 1.074 | 0.69 to 1.67 | 0.751 |

| Wealth | |||||||||

| 1st quintile | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2nd quintile | 0.639 | 0.41 to 1.01 | 0.054 | 0.628 | 0.40 to 0.99 | 0.046 | 0.611 | 0.38 to 0.97 | 0.038 |

| 3rd quintile | 0.846 | 0.57 to 1.26 | 0.410 | 0.827 | 0.55 to 1.23 | 0.351 | 0.814 | 0.55 to 1.21 | 0.313 |

| 4th quintile | 1.114 | 0.69 to 1.79 | 0.655 | 1.111 | 0.69 to 1.78 | 0.662 | 1.100 | 0.68 to 1.77 | 0.696 |

| 5th quintile | 1.169 | 0.71 to 1.91 | 0.534 | 1.142 | 0.69 to 1.88 | 0.601 | 1.118 | 0.68 to 1.85 | 0.664 |

| Disability1 | |||||||||

| No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 4.818 | 3.19 to 7.28 | <0.001 | 4.298 | 2.87 to 6.44 | <0.001 | 3.873 | 2.59 to 5.78 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 0.148 | 0.10 to 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.153 | 0.10 to 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.155 | 0.11 to 0.23 | <0.001 |

Dependent variable=moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression.

Additional disabilities (hearing, walking/climbing, remembering/concentrating, upper body, communication).

Subgroup analysis

AAPs and AMEs calculated using stored results from multivariable logistic regression models including a two-way interaction term (vision impairment with gender) show that the association between vision impairment and self-reported symptoms differed in gender subgroups (Table 4). Specifically, 28.4% of men with SVI or worse reported experiencing moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, compared with just 6.1% of women with the same vision impairment (AME = –22.3, 95% CI –33.8 to –10.8, p<0.001). Levels of anxiety and/or depression were higher for both men and women with blindness, and the observed gender gap increased slightly (AME = –24.5, 95% CI –38.3 to –10.7, p<0.001). Wald tests confirmed that interactions between SVI and gender and blindness and gender were statistically significant (p<0.001). No significant subgroup differences in the association between MVI and symptoms of either anxiety or depression or both were observed.

Table 4.

Average adjusted predictions (AAPs) and average marginal effects (AMEs) for all-cause vision impairment by gender subgroup1

| MVI (PVA<6/18) | SVI (PVA<6/60) | Blind (PVA<3/60) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (%) | 95% CI | p-value | Estimate (%) | 95% CI | p-value | Estimate (%) | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 13.5 | 7.5 to 19.6 | <0.001 | 28.4 | 17.6 to 39.2 | <0.001 | 37.6 | 24.3 to 50.9 | <0.001 |

| Female | 6.6 | 1.2 to 12.0 | 0.017 | 6.1 | –1.4 to 13.6 | 0.113 | 13.2 | 2.7 to 23.6 | 0.013 |

| Female vs Male | –6.9 | –14.0 to 0.1 | 0.054 | –22.3 | –33.8 to –10.8 | <0.001 | –24.5 | –38.3 to –10.7 | <0.001 |

Dependent variable=moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression.

AAPs and AMEs were calculated using results from a multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for gender, age, household wealth and additional disabilities and fitted with a two-way interaction term (vision impairment with gender).

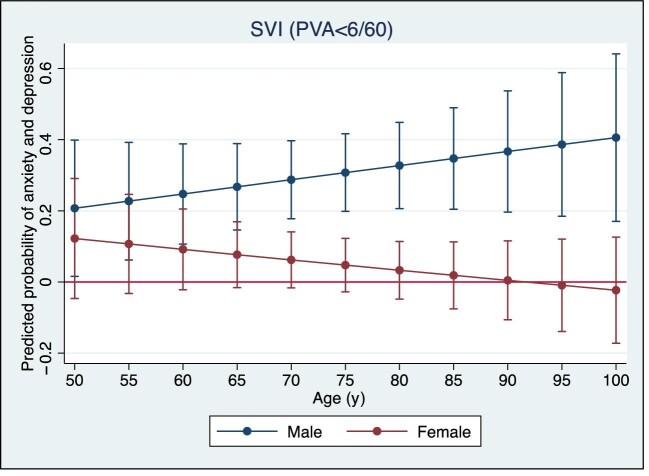

Figures 1 and 2 present AMEs calculated using results from adjusted regression models fitted with a three-way interaction term (vision impairment with gender with age). In Figure 1 the gender gap in the association between SVI and self-reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depression was greater among older individuals.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of anxiety and depression for males and females with SVI (PVA<6/60) by age.

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of anxiety and depression for males and females with blindness (PVA<3/60) by age.

Figure 2 also shows statistically significant gender differences between blindness and symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, which increased with age. In other words, older men who were blind were more likely to experience moderate to severe symptoms compared with blind women of a similar age.

Discussion

Using cross-sectional data from a population-based survey conducted in Kogi State, Nigeria, this study estimated the associations between all-cause vision impairment and self-reported symptoms of either anxiety or depression, or both, in a sample of adults aged ≥50 y. After adjusting for individual and household level confounders, the odds of anxiety and/or depression were higher among people with vision impairment compared with those with normal vision, and the odds were greatest for people with the most severe vision loss. The study also tested whether the association between vision impairment and symptoms of anxiety and/or depression differed in gender subgroups and with age. It revealed that the probability of symptoms was more than fourfold higher among men with SVI or blindness compared with women with the same vision impairment, and that for respondents who were blind, the likelihood of symptoms was also higher for men than for women. This gender gap was found to widen with age.

This study's main finding is consistent with evidence from high-income country settings that suggests vision impairment contributes to the burden of mental illness.5 However, only a small number of studies have examined the association between vision impairment and symptoms of anxiety and depression among older adults in LMICs, where the impacts of vision loss may be exacerbated by poverty and inadequate healthcare services.

Causality cannot be directly inferred from cross-sectional data, but there are several possible factors contributing to the association between vision impairment and anxiety and/or depression observed in this study. For example, previous studies have found that vision loss can lead to difficulties with daily activities, including instrumental activities of daily living that allow an individual to live independently in their community.17,18 Limited physical activity could also increase the risk from social isolation and loneliness.4 In addition, mental health and poverty are closely connected, and people in LMICs who are vision impaired are known to have fewer opportunities to engage in economically productive activities.19,20

Notably, this study found that symptoms of anxiety and/or depression were higher among men with vision impairment and blindness than among similar women, and that this gender gap widened with age. This suggests that although women are well known to be at a greater risk of developing anxiety and depression, older men may be more vulnerable to the psychosocial impacts of vision loss and related economic and social inactivity. Relatively little is understood about the relationship between gender, age and mental health, but high-income country studies have found higher levels of depression among older men compared with women, potentially explained by their covarying physical health status,21 and gender-dependent differences in the relationship between late-life depression and activity limitations.22 Social and cultural norms, differences in gender roles, as well as differences in the coping styles of men, may also account for this study's finding.23 Evidence around labour force participation in Nigeria suggests that men are more likely to be economically active outside of the home than females and may feel a greater impact of limitations imposed by later-life development of visual impairments.24

There are several important limitations that must be considered along with these findings. First, potentially unobserved confounding of the associations between vision impairment, anxiety and depression. For example, information on individual history of mental health was unavailable in the data. Second, this study relied on self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression, which are not equivalent to physician-diagnosed illness. Third, the cross-sectional design of the study prevented identification of the direction of the relationship between vision impairment and symptoms of either anxiety or depression, or both. Finally, the study did not collect data about age of onset of different conditions, making analyses of early/later life impairments impossible. Future cohort studies that could test both the causal directionality underlying the observed associations, and identify specific issues associated with age of onset of different conditions, would therefore be valuable.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study showed that the mental health burden among people with vision impairment in LMICs may be substantial, particularly among older men, underscoring the importance of targeted policies and programmes addressing the preventable causes of vision impairment and blindness.

Contributor Information

Ben Gascoyne, Sightsavers, 35 Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, RH16 3BW, UK.

Emma Jolley, Sightsavers, 35 Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, RH16 3BW, UK.

Selben Penzin, Sightsavers, 1 Golf Course Road, Kaduna, Nigeria.

Kola Ogundimu, Sightsavers, 1 Golf Course Road, Kaduna, Nigeria.

Foluso Owoeye, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Jebba Road, Ilorin, Nigeria.

Elena Schmidt, Sightsavers, 35 Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, RH16 3BW, UK.

Authors’ contributions

BG and EJ conceived the study; all authors were involved in implementation; BG, EJ, SP, KO and ES carried out analysis and interpretation of data; BG drafted the manuscript; BG, EJ and ES reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office [contract award DFID 8219].

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Before research began, data collection was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee, Kogi State of Nigeria Ministry of Health [ref. MOH/PRS/465/V.1/007] and satisfied all legal and regulatory requirements pertaining to research in Kogi State. All data used in this study were fully anonymised and contained no personal or identifying information. All study participants were given information about the study in their preferred language and an opportunity to ask questions; and participants provided individual written (or fingerprinted) consent. In addition, the head of each household or their representative gave consent for their household to participate. Minor ocular conditions identified were treated by the team. Other conditions were referred to the nearest health centre or hospital.

Data Availability

The anonymised dataset is availble from the authors on reasonable request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . World report on vision. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bourne R, Steinmetz JD, Flaxman Set al. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(2):e130–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burton MJ, Ramke J, Marques APet al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020. Lancet Global Health . 2021;9(4):e489–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ehrlich JR, Ramke J, Macleod Det al. Association between vision impairment and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(4):e418–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Assi L, Chamseddine F, Ibrahim Pet al. A global assessment of eye health and quality of life: a systematic review of systematic reviews. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(5):526–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Demmin DL, Silverstein SM. Visual impairment and mental health: unmet needs and treatment options. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parravano M, Petri D, Maurutto Eet al. Association between visual impairment and depression in patients attending eye clinics: a meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(7):753–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng Y, Wu X, Lin Xet al. The prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among eye disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen P-W, Liu PP-S, Lin S-Met al. Cataract and the increased risk of depression in general population: a 16-year nationwide population-based longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organisation (WHO) . ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Available at: https://icd.who.int/browse11/ [accessed July 31, 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kyari F, Gudlavalleti MV, Sivsubramaniam Set al. Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: The national blindness and visual impairment survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(5):2033–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso Jet al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psych Sci. 2009;18(1):23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ejiakor I, Achigbu E, Onyia Oet al. Impact of visual impairment and blindness on quality of life of patients in Owerri, IMO state, Nigeria. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2019;26(3):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuper H, Polack S, Limburg H. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness. Comm Eye Health. 2006;19(60):68–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Washington Group on Disability Statistics . The Washington Group Short Set on Functioning – Enhanced (WG-SS Enhanced). Available at: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-short-set-on-functioning—enhanced-wg-ss-enhanced [accessed July 31, 2021].

- 16. Metrics for Management . Nigeria Equity Tool. Available at: https://www.equitytool.org/nigeria/ [accessed July 31, 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lam BL, Christ SL, Zheng DDet al. Longitudinal relationships among visual acuity and tasks of everyday life: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(1):193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pérès K, Matharan F, Daien Vet al. Visual loss and subsequent activity limitations in the elderly: The French three-city cohort. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):564–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Danquah L, Kuper H, Eusebio Cet al. The long term impact of cataract surgery on quality of life, activities and poverty: results from a six year longitudinal study in Bangladesh and the Philippines. PloS One. 2014;9(4):e94140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Polack S, Kuper H, Wadud Zet al. Quality of life and visual impairment from cataract in Satkhira district, Bangladesh. Brit J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(8):1026–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burns RA, Luszcz MA, Kiely KMet al. Gender differences in the trajectories of late-life depressive symptomology and probable depression in the years prior to death. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(11):1765–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carrière I, Gutierrez LA, Pérès Ket al. Late life depression and incident activity limitations: influence of gender and symptom severity. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(1-2):42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kiely KM, Brady B, Byles J. Gender, mental health and ageing. Maturitas. 2019;129:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Enfield S. Gender roles and inequalities in the Nigerian labour market. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5d9b5c88e5274a5a148b40e5/597_Gender_Roles_in_Nigerian_Labour_Market.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymised dataset is availble from the authors on reasonable request.