Abstract

We report a case of primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma that occurred in a 25-year-old woman. The patient complained of a mass in the right ovary discerned by physical examination 2 months prior. Ultrasound examination indicated that the right ovary was enlarged and abundant blood flow signals were observed. Right salpingo-oophorectomy was subsequently performed. Histology was characterized by diffuse sheets of monotonous medium-sized lymphoid cells with plentiful mitotic figures and apoptosis. Numerous tingible-body macrophages were found in the ovarian tissue, presenting a starry sky pattern. The tumor cells expressed CD20, CD10, BCL6 and MYC in the absence of BCL2. Ki-67 proliferative index was very high with a proliferation rate of near 100%. MYC (8q24) rearrangement was detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with no BCL2 (18q21) and BCL6 (3q37) gene rearrangements. Cumulative evidence established primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma as the final histopathologic diagnosis with clinical stage I (FIGO). The patient received HyperCVAD chemotherapy after surgery and remained complete response (CR) for 18 months. We aim to provide insight into the future treatment of this rare but lethal disease.

Keywords: Primary, ovary, Burkitt lymphoma

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is an aggressive B-cell lymphoma characterized by frequent presence in extranodal sites or as acute leukemia, mostly with high proliferative activity and MYC translocation. All organs of the female genital tract can be involved, and ovarian involvement predominates in a majority of the cases [1,2]. The molecular hallmark of BL is the deregulation of MYC expression due to the translocation of MYC to an IG gene locus. Gene expression profiling has defined patterns of molecular signatures for BL [3,4]. Mutations of TCF3(E2A) and ID3 are seen in 70% of sporadic BL cases documented [5-8]. Mutations of MYC, CCDN3, TP53, RHOA, SMARCA4, AND ARID1A are present in 5-40% of BL cases [9]. About 29 cases of primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma have been reported (Table 1) [10-38]. The present study reports the clinical data, histologic morphology, immunohistochemistry, molecular characteristics, and treatment in this case in order to provide a further reference about this tumor’s diagnosis and treatment.

Table 1.

Clinical features of 26 primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma patients

| Case number | 1st author | Age | Nationality | Symptoms | Ovarian involvement | Stage | Treatment | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baloglu [28] | 24 | Turkey | Secondary amenorrhea, ascites, pleural effusion | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Chemotherapy: Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, Vincristine, L-asparaginase, Prednisolone, plus intrathecal Methotrexate | Remission; autologous bone marrow transplantation; death 35 days after transplantation |

| 2 | Vang [27] | 62 | USA | Constitutional symptoms | Unilateral | I Ann Arbor | Chemotherapy, radiotherapy | Remission |

| 3 | Hui [34] | 13 | USA | Abdominal pain | Unilateral | III Murphy staging | Surgery, chemotherapy (COPADM) | Remission |

| 4 | Liang [26] | 38 | Hong Kong, China | Abdominal pain | Unilateral | I Ann Arbor | Chemotherapy, radiotherapy | Disease-free survival (6 mouths) |

| 5 | Taylor [35] | 33 | USA | Abdominal pain | Bilateral | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy | NA |

| 6 | Miyazaki [25] | 16 | Japan | Abdominal pain, constipation | Unilateral | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy | Died after 171 days |

| 7 | Cyriac [24] | 13 | India | Abdominal pain, fever | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Chemotherapy (LMB 89 protocol) | Disease-free survival (6 mouths) |

| 8 | Crawshaw [23] | 28 | UK | Abdominal pain, pregnancy | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Chemotherapy | NA |

| 9 | Chishima [22] | 25 | Japan | Abdominal pain | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (CHOP) | Disease-free survival (30 mouths) |

| 10 | Monterroso [21] | 21 | USA | Abdominal pain | NA | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy | Died after a year |

| 11 | Ng [20] | 20 | Malaysia | Abdominal pain | Bilateral | 1B FIGO | Surgery, chemotherapy (BFM regime), plus prophylactic intrathecal Methotrexate | Remission |

| 12 | Shacham-Abulafia [18] | 39 | Isreal | Night sweats, abdominal pain, dyspnea | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Chemotherapy (R-Hyper-CVAD plus GMALL-BALL/NHL 2002) | Disease-free survival (6 mouths) |

| 13 | Bianchi [19] | 57 | Italy | Neurological symptoms | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (intensive G-mall protocol) | NA |

| 14 | Danby [17] | 11 | USA | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss | Unilateral | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy (Rituximab, Methotrexate, Cytarabine, intrathecal Hydrocortisone, Cytosine arabinoside, Methotrexate and Cyclophosphamide) | NA |

| 15 | Etonyeaku [16] | 18 | Nigeria | Abdominal pain, lower abdominal swelli | Bilateral | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy (Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Methotrexate) | Died after second chemotherapy |

| 16 | Gottwald [15] | 27 | Poland | Abdominal pain, ascites | Bilateral | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy (COP followed by CODOXM + IVAC) | Disease-free survival (3 years) |

| 17 | Gutierrez [14] | 34 | Spain | NA | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor, 3 FIGO | Surgery, chemotherapy | Died after a mouth |

| 18 | Hatami [13] | 58 | USA | Abdominal masses | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (Vincristine, Rituximab, Methotrexate with Leucovorin and intrathecal Methotrexate) | Disease-free survival (42 mouths) |

| 19 | Munoz [12] | 30 | Spain | Abdominal pain | Bilateral | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy (CODOX-M-IVAC plus Rituximab) | NA |

| 20 | Khan [11] | 6 | India | Abdominal pain and masses | Bilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (MCP-842 protocol) | NA |

| 21 | Mondal [10] | 6 | India | Abdominal pain, difficulties with walking | Bilateral | II R Murphy staging | Surgery, chemotherapy (Magrath protocol using CODOX-M regimen) | Remission |

| 22 | Gomez [29] | 13 | Spain | Abdominal pain | Unilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Cytarabine, Dexamethasone, Rituximab) | Remission |

| 23 | Xiao [30] | 19 | China | Chest tightness, asthma | Unilateral | IV Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (HyperCVAD, MTX plus Ara-c) | Deceased |

| 24 | Xiao [30] | 43 | China | Fatigue, bone pain | Unilateral | I Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (R-CHOP, HD-MTX plus VP) | Remission |

| 25 | Gravos [31] | 21 | Greek | Abdominal distension | Unilateral | I Ann Arbor | Chemotherapy | Remission |

| 26 | Al-Maghrabi [32] | 42 | Saudi Arabia | Abdominal pain | Bilateral | I Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy (R-CODOX, R-IVAC) | Remission |

| 27 | Lanjewar [36] | 28 | India | Weight loss, distension and pain | Unilateral | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy, HAART | Died after 7 mouths |

| 28 | Sergi [37] | 24 | Italy | Abdominal tenderess, diffuse pain | Unilateral | NA | Chemotherapy | NA |

| 29 | Steininger [38] | 17 | German | Abdominal pain | Unilateral | III Ann Arbor | Surgery, chemotherapy | Remission |

Abbreviation: FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, NA: Not available.

Case presentation

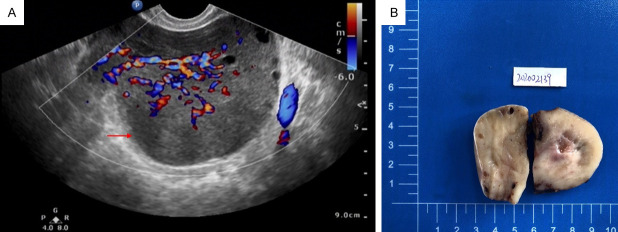

The patient was a 25-year-old married female who complained of a mass in the right ovary detected by physical examination 2 months ago. She had regular menstruation. The preoperative transvaginal ultrasound displayed that the right ovary was enlarged approximately 93 × 83 × 74 mm, and abundant blood flow signals were also observed (Figure 1A). The uterus, cervix, and left ovary were normal. The endometrium measured about 7 mm in thickness. Cervical cytology was negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM). The patient denied additional aberrant symptoms or signs upon admission. A right salpingo-oophorectomy was subsequently performed.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image and gross features of the case. A. Preoperative transvaginal ultrasound showed that the right ovary was enlarged, with abundant blood flow signals in the ovarian tissue (marked by red arrow). B. The tumor originated from the ovary and was well-circumscribed A gray-white tender cut surface and scattered hemorrhage was visible.

Gross examination

The removed right ovary measured 11 × 11 × 5 cm in size. The tumor originated from the ovary and it did not spread to the fallopian tube. It was well-circumscribed with a gray-white tender cut surface and scattered hemorrhage was visible (Figure 1B). The ipsilateral fallopian tube was grossly unremarkable.

Microscopic examination

Microscopically, the tumor obliterated normal ovarian parenchyma. The involved ovarian tissue was diffusely infiltrated by sheets of monotonous medium-sized neoplastic lymphoid cells and the boundary between the tumor tissue and ovary was unclear (Figure 2A). Innumerable neoplastic cells interspersed with scattered reactive tangible-body macrophages engulfing nuclear debris, creating a prominent “starry sky” pattern (Figure 2B). When examined at high magnification, the neoplastic cells showed molding and squaring-off of the nuclear membrane and cell membrane, with relatively uniform round or oval nuclei, coarse chromatin, multiple small nucleoli, and an appreciable rim of basophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were numerous as well as a high rate of apoptosis (Figure 2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

Histology of the ovarian tumor. A. The involved ovarian tissue was diffusely infiltrated by sheets of monotonous medium-sized neoplastic lymphoid cells and the boundary between the tumor tissue and ovary was unclear (magnification: × 40). B. Innumerable neoplastic cells interspersed with scattered reactive tangible-body macrophages engulfing nuclear debris, creating a prominent “starry sky” pattern (magnification: × 100). C and D. The neoplastic cells showed molding and squaring-off of the nuclear membrane and cell membrane, with relatively uniform round or oval nuclei, coarse chromatin, multiple small nucleoli, and an appreciable rim of basophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were numerous as well as a high rate of apoptosis (marked by red arrows). C. Magnification: × 400; D. Magnification: × 1000.

Immunohistochemical findings

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells expressed pan-B-cell antigens (CD20, CD79-a, and PAX5), germinal center markers (CD1 and BCL6), and MYC. BCL2, CD3, CD5, CD138, and TdT were negative. EBV was negative. The proliferation fraction (Ki67 index) was very high, approaching 100% (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 3.

Immunoprofile and FISH examination of tumor cells. A. Positivity for CD20 (magnification: × 400). B. High grade tumor revealed by over 100% cell positivity for Ki67 antibody (magnification: × 400). C. Positivity for BCL-6 (magnification: × 400). D. MYC (8q24) rearrangement positive cells include one fusion signal (yellow), one red signal, and one green signal in nuclei. The ratio of MYC cleavage signal positive abnormal cells per 100 cells is equal to 61%, which meets the positive diagnostic criteria (magnification: × 1000).

FISH examination

The t (8;14) (q24; q32)/IGH-MYC was detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (break-apart probes) (Figure 3D) whereas BCL2 (18q21) and BCL6 (3q37) rearrangements were absent.

The patient underwent bone marrow aspirate evaluation for hematological immunotyping and chromosomes analysis. The results were negative for malignancy and atypical chromosomes. The subsequent PET-CT showed no lesions on other organs. Combined with the clinical visualization, histologic features, immunohistochemical results, cytogenetics, and molecular test, the diagnosis was ascertained as primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma. The patient received the treatment protocol of HyperCVAD chemotherapy after surgery.

Discussion

Although primary extranodal invasive lymphoma of the ovary is a rare disease, ovarian lymphoma is typically secondary to diffuse systemic disorder. In extranodal lymphoma, primary ovarian lymphoma accounts for 0.5% of extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and 1% of all ovarian tumors [39]. Several perspectives regarding the origin of primary ovarian lymphoma have been documented: 1. Primary ovarian lymphoma originates from the lymphoid tissues that already exist in the ovary [23]; 2. The blood vessels around the hilum of the ovary or the corpus luteum cells may be tumor-derived cells [10]; 3. Reactive lymphocytes may be secondary to ovarian inflammation (pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis) or autoimmune diseases, and following processes of malignant transformation into ovarian primary lymphoma [40]. No specific association was described with EBV. Sporadic BL may coexist with EBV infection [41]. However, tests for EBV infections are also recommended. As reported in this case, the patient has no EBV infection.

Weekes first discovered primary bilateral ovarian Burkitt lymphoma in a 15-year-old girl from Guatemala in 1986 [42]. To our knowledge, about 29 cases of primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma have been reported in the literature. Among the described cases, 15 were bilateral and 10 were unilateral (1 unavailable). The age of the patients ranged from 6 to 62 years (average, 27 years old). The clinical manifestations of ovarian primary Burkitt lymphoma are unique [43]. Most patients complained of abnormal pain accompanied by additional symptoms including fever, abnormal mass, lower abdominal swelling, ascites, and vaginal bleeding [44,45]. As for our patient, the young married woman was diagnosed with a mass in the right ovary by physical examination due to infertility. Staging plays an important role in accessing disease progression and determine the individualized treatment of patients. Ann Arbor classification is mostly used in adult BL patients, while St. Jude/Murphy applies to pediatric patients. Seven of them are stage I (1 stage 1B, FIGO), 2 are stage II, 11 are stage IV, 6 unavailable. This case presented a primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma of FIGO staging 1A. The histologic findings of the present case were identical to Burkitt’s lymphoma that occurred in other organs, which are characterized by diffuse growth of medium-sized lymphoid cells with round nuclei and agglomerated chromatin [46]. Necrotic debris could be seen in the background, which was swallowed by many tissue cells, forming a typical pattern of the “starry sky”.

Primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma originates from B cells and expresses B cell markers such as CD20, CD79a, PAX5. Cytokeratin and T cell markers are negative. MYC represents a family of regulator genes and proto-oncogenes that codes for transcription factors. The MYC family consists of three related human genes c-MYC (MYC), l-MYC (MYCL), and n-MYC (MYCN). c-MYC (also sometimes referred to as MYC) is the first gene discovered in this family due to its homology with a viral gene v-MYC. In cancer, c-MYC is often expressed constitutively (persistently), which leads to an increase in the expression of multiple genes. Additionally, some of them are even involved in cell proliferation and contribute to the formation of cancer cells. Common human translocations involving c-MYC are critical to the development of most Burkitt lymphomas [13,47], and the mutation is usually t (8;14) (q24; q32) translocation. In this case, CD20 was strongly positive, the result of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was MYC (8q24) rearrangement, the morphology combined with immunohistochemical results and molecular pathologic features were consistent with the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma.

The differential diagnosis of primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma includes secondary ovarian lymphoma, High-grade B-cell lymphoma with double-hit or triple-hit, adult granular cell tumor of the ovary, and small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNEC). Fox et al. proposed the diagnostic criteria for primary ovarian lymphoma in 1988 including: 1. Lymphoma should be confined to the ovary or adjacent lymph nodes or structures at the time of diagnosis; 2. There is no evidence showing the presence of blood or bone marrow disease; 3. Distal involvement should occur at least a few months after ovarian involvement [48]. High-grade B-cell lymphoma with double-hit or triple-hit is a general term for morphologically aggressive B-cell lymphoma with MYC rearrangement and additional rearrangement of BCL2 (double-hit lymphoma, DHL) and/or BCL6 (triple-hit lymphoma, THL). Adult granular cell tumor of the ovary is frequently encountered in postmenopausal women, with the peak age of onset at 50-55 years old, which represents the most typical clinical ovarian tumor related to estrogen secretion. The nuclei are round, oval, or polygonal, lightly stained, less cytoplasm, and a nuclear groove is visible. Immunohistochemical expression of sex cord-stromal markers is seen such as α-inhibin, calretinin, FOXL2, and CD99. The epithelial markers are negative. Differential diagnosis of the disease also requires an ruling out SCNEC. SCNEC is a high-grade carcinoma composed of small to medium-sized cells with scant cytoplasm and neuroendocrine differentiation. The cytoplasm of the tumor is sparse with a small cell nucleus. Single small nucleolus can be visible and mitotic images are common. Tumor cells can be in a nested pattern, string-shaped and irregular cell clusters, and express neuroendocrine markers such as CgA, Syn, and CD56.

As Burkitt lymphoma is an aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a short and active proliferation cycle, multi-drug combination chemotherapy is considered an optimal treatment protocol for patients with Burkitt lymphoma [49,50]. The 29 cases previously reported were mostly (20/29) treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy. Surgical treatment plays an important role in providing clinical information, staging, and diagnosis, and patients with confirmed diagnosis should start chemotherapy as early as possible. Although Burkitt lymphoma is highly malignant, combined treatment with multiple chemotherapy regimens can substantially improve the survival rate of Burkitt lymphoma patients [13]. The follow-ups ranged from 0.5 to 3.5 years (average 1.6 years). Four deaths were reported, giving an overall survival rate of 15/19 (78.95%) (7 unavailable). In our case, the patient underwent right salpingo-oophorectomy and accepted HyperCVAD chemotherapy after surgery. The patient developed complete response (CR) 18 months following the completion of the therapy.

Conclusion

We report a case of a primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma that occurred in a young woman, confirmed by histological morphology, immunohistochemistry, and FISH. Further studies are of great significance to characterize clinical features of this rare disease, for differential diagnosis and effective therapy.

The reporting of this study conforms to CARE guidelines [51].

Acknowledgements

Supported by Anhui Medical University Funding Project (2020xkj066).

Informed consent has been obtained from patients included in this study.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kosari F, Daneshbod Y, Parwaresch R, Krams M, Wacker HH. Lymphomas of the female genital tract: a study of 186 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1512–1520. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000178089.77018.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasioudis D, Kampaktsis PN, Frey M, Witkin SS, Holcomb K. Primary lymphoma of the female genital tract: an analysis of 697 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dave SS, Fu K, Wright GW, Lam LT, Kluin P, Boerma EJ, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Müller-Hermelink HK, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Rimsza LM, Braziel RM, Grogan TM, Campo E, Jaffe ES, Dave BJ, Sanger W, Bast M, Vose JM, Armitage JO, Connors JM, Smeland EB, Kvaloy S, Holte H, Fisher RI, Miller TP, Montserrat E, Wilson WH, Bahl M, Zhao H, Yang L, Powell J, Simon R, Chan WC, Staudt LM Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project. Molecular diagnosis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2431–2442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hummel M, Bentink S, Berger H, Klapper W, Wessendorf S, Barth TF, Bernd HW, Cogliatti SB, Dierlamm J, Feller AC, Hansmann ML, Haralambieva E, Harder L, Hasenclever D, Kühn M, Lenze D, Lichter P, Martin-Subero JI, Möller P, Müller-Hermelink HK, Ott G, Parwaresch RM, Pott C, Rosenwald A, Rosolowski M, Schwaenen C, Stürzenhofecker B, Szczepanowski M, Trautmann H, Wacker HH, Spang R, Loeffler M, Trümper L, Stein H, Siebert R Molecular Mechanisms in Malignant Lymphomas Network Project of the Deutsche Krebshilfe. A biologic definition of Burkitt’s lymphoma from transcriptional and genomic profiling. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2419–2430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Love C, Sun Z, Jima D, Li G, Zhang J, Miles R, Richards KL, Dunphy CH, Choi WW, Srivastava G, Lugar PL, Rizzieri DA, Lagoo AS, Bernal-Mizrachi L, Mann KP, Flowers CR, Naresh KN, Evens AM, Chadburn A, Gordon LI, Czader MB, Gill JI, Hsi ED, Greenough A, Moffitt AB, McKinney M, Banerjee A, Grubor V, Levy S, Dunson DB, Dave SS. The genetic landscape of mutations in Burkitt lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1321–1325. doi: 10.1038/ng.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter J, Schlesner M, Hoffmann S, Kreuz M, Leich E, Burkhardt B, Rosolowski M, Ammerpohl O, Wagener R, Bernhart SH, Lenze D, Szczepanowski M, Paulsen M, Lipinski S, Russell RB, Adam-Klages S, Apic G, Claviez A, Hasenclever D, Hovestadt V, Hornig N, Korbel JO, Kube D, Langenberger D, Lawerenz C, Lisfeld J, Meyer K, Picelli S, Pischimarov J, Radlwimmer B, Rausch T, Rohde M, Schilhabel M, Scholtysik R, Spang R, Trautmann H, Zenz T, Borkhardt A, Drexler HG, Möller P, MacLeod RA, Pott C, Schreiber S, Trümper L, Loeffler M, Stadler PF, Lichter P, Eils R, Küppers R, Hummel M, Klapper W, Rosenstiel P, Rosenwald A, Brors B, Siebert R ICGC MMML-Seq Project. Recurrent mutation of the ID3 gene in Burkitt lymphoma identified by integrated genome, exome and transcriptome sequencing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1316–1320. doi: 10.1038/ng.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sander S, Calado DP, Srinivasan L, Kochert K, Zhang B, Rosolowski M, Rodig SJ, Holzmann K, Stilgenbauer S, Siebert R, Bullinger L, Rajewsky K. Synergy between PI3K signaling and MYC in Burkitt lymphomagenesis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitz R, Young RM, Ceribelli M, Jhavar S, Xiao W, Zhang M, Wright G, Shaffer AL, Hodson DJ, Buras E, Liu X, Powell J, Yang Y, Xu W, Zhao H, Kohlhammer H, Rosenwald A, Kluin P, Muller-Hermelink HK, Ott G, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Rimsza LM, Campo E, Jaffe ES, Delabie J, Smeland EB, Ogwang MD, Reynolds SJ, Fisher RI, Braziel RM, Tubbs RR, Cook JR, Weisenburger DD, Chan WC, Pittaluga S, Wilson W, Waldmann TA, Rowe M, Mbulaiteye SM, Rickinson AB, Staudt LM. Burkitt lymphoma pathogenesis and therapeutic targets from structural and functional genomics. Nature. 2012;490:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giulino-Roth L, Wang K, MacDonald TY, Mathew S, Tam Y, Cronin MT, Palmer G, Lucena-Silva N, Pedrosa F, Pedrosa M, Teruya-Feldstein J, Bhagat G, Alobeid B, Leoncini L, Bellan C, Rogena E, Pinkney KA, Rubin MA, Ribeiro RC, Yelensky R, Tam W, Stephens PJ, Cesarman E. Targeted genomic sequencing of pediatric Burkitt lymphoma identifies recurrent alterations in antiapoptotic and chromatin-remodeling genes. Blood. 2012;120:5181–5184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mondal SK, Bera H, Mondal S, Samanta TK. Primary bilateral ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma in a six-year-old child: report of a rare malignancy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10:755–757. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.136026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan WA, Deshpande KA, Kurdukar M, Patil P, Mahure H, Pawar V. Primary Burkitt’s lymphoma of endometrium and bilateral ovaries in a 6-year-old female: report of a rare entity and review of the published work. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:1484–1487. doi: 10.1111/jog.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz Martin AJ, Perez Fernandez R, Vinuela Beneitez MC, Martinez Marin V, Marquez-Rodas I, Sabin Dominguez P, Garcia Alfonso P. Primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2008;10:673–675. doi: 10.1007/s12094-008-0270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatami M, Whitney K, Goldberg GL. Primary bilateral ovarian and uterine Burkitt’s lymphoma following chemotherapy for breast cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281:697–702. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez-Garcia L, Medina Ramos N, Garcia Rodriguez R, Barber MA, Arias MD, Garcia JA. Bilateral ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30:231–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottwald L, Korczynski J, Gora E, Pasz-Walczak G, Jesionek-Kupnicka D, Bienkiewicz A. Abdominal Burkitt lymphoma mimicking the ovarian cancer. Case report and review of the literature. Ginekol Pol. 2008;79:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etonyeaku AC, Akinsanya OO, Ariyibi O, Aiyeyemi AJ. Chylothorax from bilateral primary Burkitt’s lymphoma of the ovaries: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:635121. doi: 10.1155/2012/635121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danby CS, Allen L, Moharir MD, Weitzman S, Dumont T. Non-hodgkin B-cell lymphoma of the ovary in a child with Ataxia-telangiectasia. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:e43–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shacham-Abulafia A, Nagar R, Eitan R, Levavi H, Sabah G, Vidal L, Shpilberg O, Raanani P. Burkitt’s lymphoma of the ovary: case report and review of the literature. Acta Haematol. 2013;129:169–174. doi: 10.1159/000345248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bianchi P, Torcia F, Vitali M, Cozza G, Matteoli M, Giovanale V. An atypical presentation of sporadic ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma: case report and review of the literature. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng SP, Leong CF, Nurismah MI, Shahila T, Jamil MA. Primary Burkitt lymphoma of the ovary. Med J Malaysia. 2006;61:363–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monterroso V, Jaffe ES, Merino MJ, Medeiros LJ. Malignant lymphomas involving the ovary. A clinicopathologic analysis of 39 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:154–170. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chishima F, Hayakawa S, Ohta Y, Sugita K, Yamazaki T, Sugitani M, Yamamoto T. Ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma diagnosed by a combination of clinical features, morphology, immunophenotype, and molecular findings and successfully managed with surgery and chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(Suppl 1):337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawshaw J, Sohaib SA, Wotherspoon A, Shepherd JH. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the ovaries: imaging findings. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:e155–158. doi: 10.1259/bjr/35049074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cyriac S, Srinivas L, Mahajan V, Sundersingh S, Sagar TG. Primary Burkitt’s lymphoma of the ovary. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7:120–121. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.62850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyazaki N, Kobayashi Y, Nishigaya Y, Momomura M, Matsumoto H, Iwashita M. Burkitt lymphoma of the ovary: a case report and literature review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:1363–1366. doi: 10.1111/jog.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang R, Chiu E, Loke SL. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas involving the female genital tract. Hematol Oncol. 1990;8:295–299. doi: 10.1002/hon.2900080507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vang R, Medeiros LJ, Warnke RA, Higgins JP, Deavers MT. Ovarian non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of eight primary cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:1093–1099. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baloglu H, Turken O, Tutuncu L, Kizilkaya E. 24-year-old female with amenorhea: bilateral primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:449–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomez Alarcon A, Quesada Fernandez MN, Parras Onrubia F, Diaz Serrano MD, Quesada Villar J, Hernandez Aznar JF. Ovarian Burkitt lymphoma as the primary manifestation: a case report and literature review. Medwave. 2019;19:e7674. doi: 10.5867/medwave.2019.07.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao C, Chen SR, Wang CC, Shen MH, Cao D, Lyu JH. Clinicopathological analysis of bilateral ovarian Burkitt lymphoma. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:1180–1182. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200227-00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gravos A, Sakellaridis K, Tselioti P, Katsifa K, Grammatikopoulou V, Nodarou A, Sarantos K, Tourtoglou A, Tsovolou E, Tsapas C, Prekates A. Burkitt lymphoma of the ovaries mimicking sepsis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:285. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1828-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Maghrabi H, Meliti A. Primary bilateral ovarian Burkitt lymphoma; a rare issue in gynecologic oncology. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy113. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjy113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aldoss IT, Weisenburger DD, Fu K, Chan WC, Vose JM, Bierman PJ, Bociek RG, Armitage JO. Adult Burkitt lymphoma: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22:1508–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui D, Rewerska J, Slater BJ. Appendiceal and ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma presenting as acute appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2018;32:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor JS, Frey MK, Fatemi D, Robinson S. Burkitt’s lymphoma presenting as ovarian torsion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:e4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanjewar DN, Dongaonkar DD. HIV-associated primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of ovary: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:590–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sergi W, Marchese TRL, Botrugno I, Baglivo A, Spampinato M. Primary ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma presentation in a young woman: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;83:105904. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.105904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steininger H, Gruden J, Muller H. Primary Burkitt’s lymphoma of the ovary in early weeks of pregnancy - a case report. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2012;72:949–952. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu SC, Shen WL, Cheng YM, Chou CY, Kuo PL. Burkitt’s lymphoma mimicking a primary gynecologic tumor. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;45:162–166. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crasta JA, Vallikad E. Ovarian lymphoma. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2009;30:28–30. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.56333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurzu S, Bara T, Bara TJ, Turcu M, Mardare CV, Jung I. Gastric Burkitt lymphoma: a case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8954. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weekes LR. Burkitt’s lymphoma of the ovaries. J Natl Med Assoc. 1986;78:609–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferry JA. Burkitt’s lymphoma: clinicopathologic features and differential diagnosis. Oncologist. 2006;11:375–383. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-4-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao C, Liu T, Lou S, Liu W, Shen K, Xiang B. Unusual presentation of duodenal plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompetent patient: a case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2539–2542. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhartiya R, Kumari N, Mallik M, Singh RV. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the ovary - a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ED10–11. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19346.7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenwald A, Ott G. Burkitt lymphoma versus diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl 4):iv67–69. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hecht JL, Aster JC. Molecular biology of Burkitt’s lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:3707–3721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.21.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fox H, Langley FA, Govan AD, Hill AS, Bennett MH. Malignant lymphoma presenting as an ovarian tumour: a clinicopathological analysis of 34 cases. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;95:386–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbasoglu L, Gun F, Salman FT, Celik A, Unuvar A, Gorgun O. The role of surgery in intraabdominal Burkitt’s lymphoma in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:236–239. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evens AM, Danilov A, Jagadeesh D, Sperling A, Kim SH, Vaca R, Wei C, Rector D, Sundaram S, Reddy N, Lin Y, Farooq U, D’Angelo C, Bond DA, Berg S, Churnetski MC, Godara A, Khan N, Choi YK, Yazdy M, Rabinovich E, Varma G, Karmali R, Mian A, Savani M, Burkart M, Martin P, Ren A, Chauhan A, Diefenbach C, Straker-Edwards A, Klein AK, Blum KA, Boughan KM, Smith SE, Haverkos BM, Orellana-Noia VM, Kenkre VP, Zayac A, Ramdial J, Maliske SM, Epperla N, Venugopal P, Feldman TA, Smith SD, Stadnik A, David KA, Naik S, Lossos IS, Lunning MA, Caimi P, Kamdar M, Palmisiano N, Bachanova V, Portell CA, Phillips T, Olszewski AJ, Alderuccio JP. Burkitt lymphoma in the modern era: real-world outcomes and prognostication across 30 US cancer centers. Blood. 2021;137:374–386. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2:38–43. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]