Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination produces neutralizing antibody responses that contribute to better clinical outcomes. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the N-terminal domain (NTD) of the spike trimer (S) constitute the two major neutralizing targets for antibodies. Here, we use NTD-specific probes to capture anti-NTD memory B cells in a longitudinal cohort of infected individuals, some of whom were vaccinated. We found 6 complementation groups of neutralizing antibodies. 58% targeted epitopes outside the NTD supersite, 58% neutralized either Gamma or Omicron, and 14% were broad neutralizers that also neutralized Omicron. Structural characterization revealed that broadly active antibodies targeted three epitopes outside the NTD supersite including a class that recognized both the NTD and SD2 domain. Rapid recruitment of memory B cells producing these antibodies into the plasma cell compartment upon re-infection likely contributes to the relatively benign course of subsequent infections with SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Omicron.

Keywords: anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies, SARS-CoV-2

Graphical abstract

Most neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 NTD characterized to date bind a single supersite, but these antibodies were obtained by methods that were not NTD-specific. Wang et al. analyzed SARS-CoV-2 NTD-specific memory B cell responses in a longitudinal cohort of infected individuals, some of whom were vaccinated. Structural analysis revealed neutralizing epitopes conserved among variants of concern outside the NTD supersite.

Introduction

Several independent studies purified anti-SARS-CoV-2 specific B cells from infected or vaccinated individuals using soluble spike (S) protein as a bait. In all cases, the neutralizing antibodies obtained by this method targeted the receptor-binding domain (RBD) most frequently and were generally more potent than those targeting the N-terminal domain (NTD) (Kreer et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Tong et al., 2021; Zost et al., 2020b).

Further characterization of the neutralizing antibodies to RBD showed that infected or vaccinated humans produce a convergent set of neutralizing antibodies dominated by specific immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy-chain variable (IGVH) regions (Barnes et al., 2020b; Brouwer et al., 2020; Robbiani et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021c; Yuan et al., 2020). Structural analysis of the interaction between these antibodies and the RBD revealed four classes of anti-RBD antibodies, each of which can interfere with the interaction between this domain and ACE2, the cellular receptor for the SARS-CoV-2 S protein (Barnes et al., 2020a; Yuan et al., 2020). The most frequently occurring anti-RBD antibodies select for resistance mutations in in vitro experiments that are also found in variants of concern (Baum et al., 2020; Greaney et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021c; Weisblum et al., 2020). These include the K417N, E484A, and N501Y changes that are found in Omicron, the most recently emerging variant of concern (Callaway, 2021). However, anti-RBD antibodies that remain resistant to these changes evolve over time in the memory B cell compartment of both naturally infected and vaccinated individuals over time (Cho et al., 2021; Muecksch et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b).

Less is known about anti-NTD antibody responses. In contrast to RBD, the anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies obtained to date primarily target a single supersite consisting of variable loops flanked by glycans (Amanat et al., 2021; Cerutti et al., 2021b; Chi et al., 2020; Dussupt et al., 2021; Haslwanter et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021a; Planas et al., 2021b; Suryadevara et al., 2021b; Voss et al., 2021). Residues in the supersite are mutated in several variants of concern including Beta, Gamma, and Omicron—the latter of which carries 3 deletions, 4 amino acid substitutions, and an insertion in the NTD that render antibodies to the supersite ineffective (Callaway, 2021; Faria et al., 2021; Tegally et al., 2021). Residues in this site are also mutated in the S protein of PMS20, a synthetic construct that is highly antibody resistant, and chimeric proteins built from WT and PMS20 proteins show that NTD-specific antibodies are an important component of the neutralizing activity in convalescent and vaccine recipient plasma (Schmidt et al., 2021b). NTD supersite mutations are therefore likely to contribute to the poor plasma neutralizing activity against the Omicron variant in individuals that received 2 doses of currently available vaccines or convalescent individuals exposed to pre-Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Nevertheless, boosting with currently available mRNA vaccines elicits high levels of plasma Omicron-neutralizing antibodies (Dejnirattisai et al., 2022; Gruell et al., 2022; Rossler et al., 2022; Schmidt et al., 2021a; Wu et al., 2022), and vaccinated individuals are protected from serious disease following Omicron infection. Whether additional anti-NTD Omicron-neutralizing epitopes exist and how memory B cell anti-NTD neutralizing responses evolve over time remain poorly understood.

To focus on the development and evolution of the human antibody response to NTD, we studied a cohort of SARS-CoV-2 convalescent and/or mRNA vaccinated individuals using the isolated NTD domain as a probe to capture memory B cells producing antibodies specific to this domain. We isolated 275 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) across 6 participants, of which 103 (37.5%) neutralized at least one of three strains, Wuhan-Hu-1, Gamma, or PMS20. Among the 43 neutralizing antibodies that were further characterized, we found 6 complementation groups based on competition binding experiments. Three of the broad neutralizers were characterized structurally. C1520 and C1791 recognize epitopes on opposite faces of the NTD with a distinct binding pose relative to previously described antibodies allowing for greater potency and cross-reactivity with 7 different variants including Beta, Delta, Gamma, and Omicron. Antibody C1717 represents a previously uncharacterized class of NTD-directed antibodies that recognizes the viral membrane proximal side of the NTD and SD2 domain, leading to cross-neutralization of Beta, Gamma, and Omicron. In conclusion, SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or mRNA vaccination produces a diverse collection of memory B cells that produce anti-NTD antibodies some of which can neutralize variants of concern.

Results

Vaccination boosts anti-NTD plasma-binding activity

To examine the development of anti-NTD antibodies, we studied a previously described longitudinal cohort of individuals sampled 1.3 and 12 months after infection, some of whom received an mRNA vaccine approximately 40 days before the 12-month study visit (Wang et al., 2021b; Table S1). All individuals were infected between April 1 and May 8 of 2020, before the emergence of Omicron. Antibody reactivity in plasma to the isolated Wuhan-Hu-1 and Omicron NTD was measured by ELISA (Figure 1 ). There was no association between IgM, IgG, or IgA anti-NTD Wuhan-Hu-1 or Omicron ELISA titers and age, sex, symptom severity, duration of symptoms, persistence of symptoms, or time between symptom onset and the first clinic visit (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Vaccination boosts anti-NTD plasma-binding activity during convalescence

(A and B) Plasma IgG antibody binding to Wuhan-Hu-1 NTD (A) and Omicron NTD protein (B) in unvaccinated and vaccinated (vac) convalescent individuals at 1.3 months (Robbiani et al., 2020) and 12 months (Wang et al., 2021b) after infection (n = 62). Graphs showing ELISA curves from individuals 1.3 months after infection (black lines) and from individuals 12 months after infection unvaccinated (blue lines) and vaccinated (red lines) (left panels). Area under the curve (AUC) over time in non-vaccinated and vaccinated individuals, as indicated (middle panels). Lines connect longitudinal samples. Two outliers who received their first dose of vaccine 24–48 h before sample collection are depicted in purple. Numbers in red indicate geometric mean AUC at the indicated timepoint.

(C and D) Same as (A), shown as IgM (C) and IgA (D) antibody-binding to SARS-CoV-2 NTD 1.3 and 12 months after infection. Statistical significance was determined using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests. Right panel shows combined values as a dot plot for all individuals. Statistical significance was determined through the Kruskal Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

In convalescent individuals that had not been vaccinated, anti-Wuhan-Hu-1 NTD IgG reactivity was not significantly different between the 1.3- and 12-month time points (Figure 1A, p < 0.0001). In contrast, IgG reactivity to the Omicron NTD dropped significantly between the 2 time points (Figure 1B, p < 0.0001). Notably, there was no correlation between NTD and RBD IgG ELISA reactivity or NTD IgG ELISA reactivity and plasma geometric mean half-maximal neutralizing titers (NT50s, see below) in convalescent individuals that had not been vaccinated (Figure S2). Vaccination of convalescent individuals resulted in significantly increased IgG ELISA reactivity to both Wuhan-Hu-1 and Omicron NTDs with a positive correlation between NTD and RBD ELISA, and NTD and plasma NT50 (Figures S2A and S2B; r = 0.70, p < 0.0001 and r = 0.77, p < 0.0001, respectively; Schmidt et al., 2021a). IgM and IgA anti-NTD reactivity in plasma was relatively low in all individuals tested, and only IgA was boosted with vaccination (Figures 1C and 1D). We conclude that anti-NTD ELISA reactivity to both Wuhan-Hu-1 and Omicron is enhanced by vaccination in convalescent individuals.

Memory B cell-derived anti-NTD antibodies evolve over time

Nearly all anti-NTD antibodies characterized to date were obtained using the intact S protein to capture specific memory B cells. Neutralizing anti-NTD antibodies obtained by this method represent a small subset of the total anti-S antibodies, and in most cases, they target a single carbohydrate-flanked epitope that faces away from the cell membrane and is mutated in several variants of concern including Omicron (Amanat et al., 2021; Cerutti et al., 2021b; Chi et al., 2020; Dussupt et al., 2021; Haslwanter et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021a; Planas et al., 2021b; Suryadevara et al., 2021b; Voss et al., 2021). To focus on NTD, we used a combination of soluble Wuhan-Hu-1 and Gamma NTD proteins to identify memory B cells producing antibodies specific for this domain. We reasoned that antibodies that bind both could have increased breadth because they should tolerate mutations in the Gamma NTD that alter its structure relative to Wuhan-Hu-1 (Zhang et al., 2021).

Convalescent individuals that had not been vaccinated showed a small but significant decrease (p = 0.0049) in the number of anti-NTD memory B cells between the 1.3- and 12-month time points that was boosted by vaccination (Figures 2A and S3). We obtained 914 anti-NTD antibody sequences from 3 non-vaccinated and 3 vaccinated convalescent individuals assayed at the 2 time points (Figure 2B; Table S2). Like the anti-RBD response, different individuals made closely related antibodies to NTD among which antibodies encoded by VH1-24, VH3-30, VH3-33, VH4-4, and VH4-39 were over-represented (Figures 2C and S4).

Figure 2.

Sequences of anti-NTD memory B cell antibodies suggest evolution

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing dual PE-Wuhan-Hu-1 and AlexaFluor-647-Gamma NTD binding B cells for 6 individuals (vaccinees, n = 3; non-vaccinees, n = 3) at 1.3 months (Robbiani et al., 2020) and 12 months (Wang et al., 2021b). Gating strategy is found in Figure S3. Right panel shows number of NTD/mutant NTD positive B cells per 10 million B cells (also see in Figures S3B and 3C) obtained at 1.3 months and 12 months from 39 randomly selected individuals (vaccinees, n = 18; non-vaccinees, n = 21). Graphs showing dot plots from individuals 1.3 months after infection (black) and non-vaccinated convalescents (blue) or vaccinated convalescents (red) 12 months after infection. Each dot is one individual. Red horizontal bars indicate mean values. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests.

(B) Pie charts show the distribution of antibody sequences from 6 individuals after 1.3 months (upper panel) or 12 months (lower panel). The number in the inner circle indicates the number of sequences analyzed for the individual denoted above the circle. Pie slice size is proportional to the number of clonally related sequences. The black outline indicates the frequency of clonally expanded sequences detected. Colored slices indicate persisting clones (same IGHV and IGLV genes, with highly similar CDR3s) found at both timepoints in the same patient. Gray slices indicate clones specific to the timepoint. The percentage of B cell receptor (BCR) clonality from each individual was summarized in the right panel. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank tests.

(C) Circus plot depicts the relationship between antibodies that share V and J gene segment sequences at both IGH and IGL. Purple, green, and gray lines connect related clones, clones and singles, and singles to each other, respectively. Vaccinees are marked in red.

(D) Number of nucleotide somatic hypermutations (SHM) in IGHV + IGLV in all sequences detected 1.3 months or 12 months after infection, compared with SHM in IGHV + IGLV of sequences from persisting clones, unique clones, and singlets. Statistical significance was determined using Kruskal Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

Expanded clones of memory B cells were found at both time points. On average expanded clones accounted for 22% and 27% of all antibodies at the 1.3- and 12-month time points respectively, and 30 out of 90 such clones were conserved between time points (Figure 1B; Table S2) (Robbiani et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021b). Thus, most of the clones were unique to one of the two time points indicating that the antibody response continued to evolve with persisting clonal expansion. B cell clonal evolution is associated with accumulation of somatic hypermutation (Elsner and Shlomchik, 2020; Victora and Nussenzweig, 2012). Consistent with the notion that the anti-NTD antibody response continues to evolve there was a significant increase in Ig heavy- and/or light-chain somatic mutation between the 2 time points in all 6 individuals examined (Figures 2D and S5A, p < 0.0001). CDR3 length was unchanged over time and hydrophobicity was slightly lower for anti-NTD antibodies than control (Figures S5B and S5C).

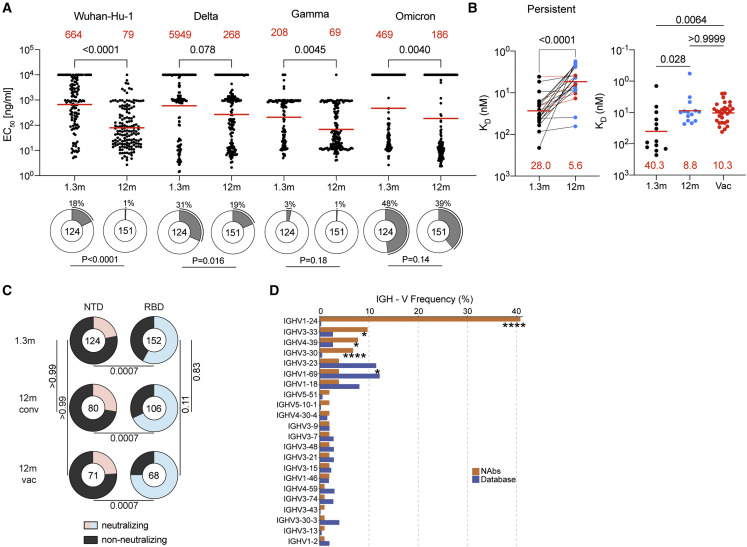

We expressed 275 antibodies from the 6 individuals (124 and 151 from 1.3- and 12-month timepoint, respectively) including: (1) 158 that were randomly selected from those that appeared only once evenly divided between 1.3- and 12-months, (2) 29 that appeared as expanded clones that were conserved at the two time points, and (3) 16 and 43 newly arising expanded clones present at either the 1.3- or 12-month time points (Table S3). Each of the antibodies was tested for binding to Wuhan-Hu-1, Delta, Gamma, and Omicron NTDs by ELISA (Figure 3A). 97% of the antibodies cloned from the 1.3-month time point bound to the Gamma NTD, and 82%, 69% and 52% to Wuhan-Hu-1, Delta, and Omicron respectively. The fraction of binding antibodies to Wuhan-Hu-1 and Delta NTD improved significantly after 12 months (Figure 3A and S6A, Wuhan-Hu-1: p < 0.0001 and Delta: p = 0.016). In addition, the geometric mean ELISA half-maximal concentration (EC50) decreased significantly for all Gamma and Omicron NTDs after 12 months suggesting an increase in overall binding affinity over time (Figure 3A, Gamma NTD: p = 0.0045 and Omicron NTD: p = 0.0040; Table S3).

Figure 3.

Anti-NTD antibodies bind and neutralize SARS-CoV-2

(A) Dot plots show EC50s against SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1-, Delta-, Gamma-, or Omicron-NTD for mAbs isolated from convalescents individuals at 1.3 and 12 months after infection. Each dot represents an individual antibody. Red horizontal bars indicate geometric mean values. Statistical significance was determined through the two-sided Kruskal-Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons. Pie charts illustrate the fraction of binders (EC50 0–10,000 ng/mL, white slices) and non-binders (EC50 = 10,000 ng/mL, gray slices). Inner circle shows the number of antibodies tested per group. The black outline indicates the percentage of non-binders. Statistical significance was determined with two-sided Fisher exact test.

(B) Graphs depict affinity measurements for mAbs obtained 1.3 and 12 months after infection. Left panel shows dissociation constants KD values for 22 clonally paired antibodies. Right panel shows KD values for randomly selected antibodies. Antibodies from individuals 1.3 months after infection are in black, and antibodies from non-vaccinated convalescents 12 months after infection are in blue or vaccinated in red. Statistical significance was determined with two-sided Kruskal-Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons. Horizontal bars indicate geometric mean values. Statistical significance was determined using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests.

(C) Pie charts illustrate the fraction of neutralizing (colored slices) and non-neutralizing (IC50 > 1,000 ng/mL, gray slices) anti-NTD (left) and anti-RBD (Wang et al., 2021b) (right) monoclonal antibodies; inner circle shows the number of antibodies tested per group. Statistical significance was determined with Fisher exact test with subsequent Bonferroni-Dunn correction.

(D) Graph shows comparison of the frequency distributions of human IGHV genes of anti-SARS-CoV-2 NTD neutralizing antibodies from donors at 1.3 months (Robbiani et al., 2020) and 12 months (Wang et al., 2021b) after infection. Statistical significance was determined by two-sided binomial test.

To determine whether antibody affinity increased between the two time points, we performed biolayer interferometry experiments. Between 1.3- and 12-month affinity to the Wuhan-Hu-1 NTD increased among persistent clones (28.0 nM to 5.6 nM) and antibodies found uniquely at one time point (40.3 nM to 8.8 nM in unvaccinated or to 10.3 nM in vaccinated individuals) (Figure 3B). We conclude that anti-NTD antibodies evolve to higher affinity during the 12 months following infection irrespective of subsequent vaccination.

Anti-NTD antibodies neutralize SARS-CoV-2 variants

Antibodies that showed binding to NTD by ELISA were tested for neutralizing activity in a SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay using pseudotyped viruses encoding Wuhan-Hu-1, Gamma, and PMS20 S proteins (Table S3). Among 275 NTD-binding antibodies, 103 neutralized at least one of the pseudoviruses with an IC50 of less than 1,000 ng/mL (Table S3). The fraction of Wuhan-Hu-1-neutralizers among the anti-NTD antibodies obtained from convalescent individuals was 22%, 28%, and 24% at 1.3-month, 12-month, and 12-month vaccinated individuals, respectively. In contrast, the overall neutralizing activity among anti-RBD antibodies obtained from the same time points from this cohort was significantly higher in all cases (58%, 68%, and 75% respectively) (Figure 3C, p = 0.0007; Robbiani et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021b). Anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies were significantly enriched in IGVH1-24, IGVH3-33, and IGVH3-30, all of which are enriched among neutralizing antibodies that target the NTD supersite (Figure 3D, p < 0.0001: Table S4) (Amanat et al., 2021; Cerutti et al., 2021b; Chi et al., 2020; Dussupt et al., 2021; Haslwanter et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021a; Planas et al., 2021b; Suryadevara et al., 2021b; Voss et al., 2021). IGVH1-24 was frequently associated with IGVL1-51, which is also over-represented among neutralizers compared with the database (Table S4). The neutralizers obtained by this method were also enriched in VH4-39, which has not been associated with NTD supersite neutralizing activity (Figure 3D).

Among the antibodies tested, the geometric mean IC50 against Wuhan-Hu-1, Gamma, and PMS20 was similar at 1.3- and 12-months (Figures 4A and S6C; Table S3). Vaccination was associated with increased neutralizing activity at 12 months against Gamma but not the other two pseudoviruses tested (Figure 4A). There was also no change in geometric mean IC50 when only the conserved clones were considered (Figure S6D). Therefore, there is no general increase in anti-NTD antibody neutralizing activity over time despite the relative increase in affinity.

Figure 4.

Anti-NTD antibodies exhibit potency and breath against SARS-CoV-2 variants

(A) Graph shows anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing activity of monoclonal antibodies measured by a SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assay(Robbiani et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020). Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for antibodies isolated at 1.3 and 12 months after infection in non-vaccinated (1.3m/12m conv) and convalescent vaccinated (12m vac) participants. IC50s against Wuhan-Hu-1, Gamma, and PMS20 (Schmidt et al., 2021b) SARS-CoV-2. Spike plasmids are based on Wuhan-Hu-1 strain containing the R683G substitution. Each dot represents one antibody from individuals 1.3 months after infection (black) and non-vaccinated convalescents (blue) or vaccinated convalescents (red) 12 months after infection. Statistical significance was determined by two-sided Kruskal-Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons. Horizontal bars and red numbers indicate geometric mean values.

(B) Heatmap showing neutralizing activity and VH groups of 103 neutralizing antibodies against Wuhan-Hu-1, Gamma, and PMS20 SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus. IC50 values are indicated by color (from blue to red, most potent to least potent).

(C) IC50 values for n = 6 broadly neutralizing NTD antibodies against the indicated variant SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses, PMS20 (Schmidt et al., 2021b) and SARS-CoV pseudovirus (Muecksch et al., 2021) (left) as well as wild-type (WT) (WA1/2020) (Robbiani et al., 2020) and Beta (B.1.351) authentic virus.

(D) Neutralization curves for the antibodies in (C) against Wuhan-Hu-1 pseudovirus.

(E) Neutralization curves for the antibodies in (D), against WT (WA1/2020) and Beta (B.1.351) authentic virus.

Although the neutralizing activity of the NTD antibodies was generally lower than RBD antibodies cloned from the same time points from this cohort (Figures 4A and S6C) (Robbiani et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021b), some anti-NTD antibodies were very potent with IC50 values as low as 0.17 ng per milliliter (Figure 4A). Of the 103 neutralizing anti-NTD antibodies with demonstrable neutralizing activity, 14 were specific for Wuhan-Hu-1, 20 were limited to Gamma, and 13 were PMS20- specific (Figure 4B). The remaining 56 antibodies neutralized two or more viruses (Figure 4B). Antibodies targeting the NTD supersite are enriched in VH1-24, VH3-30, and VH3-33, and these three VH genes account for 59 of the 103 antibodies tested (Figures 3D, 4B, and S6E; Table S4). Notably, despite its mutations in the NTD supersite, 24 antibodies neutralized PMS20 and six neutralized all three viruses, suggesting that some of these antibodies might bind to epitopes outside of the supersite.

To document the neutralizing breadth of the six broadest antibodies, we tested them against viruses pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2 Alpha, Beta, Delta, Iota, and Omicron and SARS-CoV S proteins (Figure 4C). Although none of the antibodies neutralized SARS-CoV, four of the six antibodies neutralized all strains tested albeit at relatively high neutralizing concentrations. However, pseudovirus neutralization was incomplete even at very high antibody concentrations for two of the more potent antibodies tested (Figure 4D).

To determine whether intact virus neutralization resembles pseudovirus neutralization, we performed microneutralization experiments using authentic SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020 (Robbiani et al., 2020) and SARS-CoV-2 Beta. In contrast to the pseudovirus, the two antibodies that showed the most incomplete neutralization profiles against pseudovirus, C1520 and C1565, reached complete neutralization and were exquisitely potent with IC50s in the low nanogram per milliliter range against both strains (Figures 4C and 4E). We conclude that some naturally arising memory anti-NTD antibodies produced in response to Wuhan-Hu-1 infection and immunization are insensitive to the mutations found in Omicron and other variants of concern.

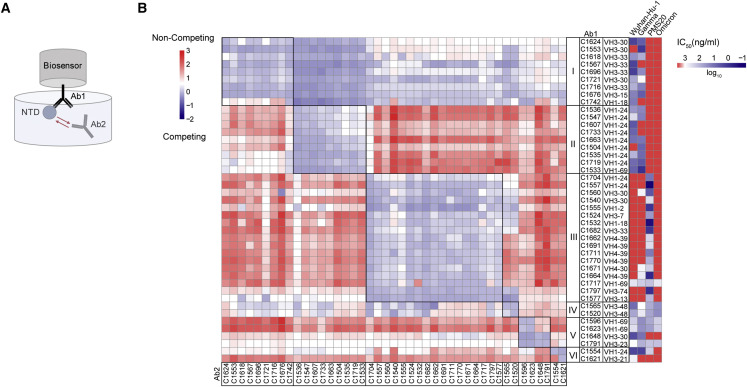

Anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies form six complementation groups

To determine whether our collection of anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies target overlapping epitopes, we performed biolayer interferometry competition experiments (Figure 5 ). Among the 43 antibodies with the highest neutralizing activity tested, there were 6 discernible complementation groups. Groups I and II were overlapping and highly enriched in VH3-30, VH3-33, and VH1-24, respectively, which accounted for nearly 90% of the antibodies in these two groups (Figure 5B). These antibodies neutralized either or both Wuhan-Hu-1 and Gamma, but none neutralized PMS20 or omicron that are mutated in the NTD supersite. Thus, these 2 groups of antibodies appear to target the previously defined supersite on NTD (Amanat et al., 2021; Cerutti et al., 2021b; Chi et al., 2020; Dussupt et al., 2021; Haslwanter et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021a; Planas et al., 2021b; Suryadevara et al., 2021b; Voss et al., 2021). Group III and IV are also overlapping, but in contrast, in groups III and IV, only 3 of the 19 neutralize Wuhan-Hu-1, and those that do are broad. Notably, the remaining antibodies fail to measurably neutralize Wuhan-Hu-1 but neutralize PMS20 and/or Omicron (Figure 5B; Table S4). Unlike other VH1-24-encoded antibodies that fall into complementation group II, C1704 and C1557 in group III only neutralize PMS20 but no other strains, suggesting the mechanism of their neutralization might be unusual. Group V contains four members, three of which are broad. The final group VI contains 2 members, C1621 only neutralizes Wuhan-Hu-1, and C1554 neutralized broadly but not potently. The broadest neutralizing anti-NTD antibodies appear to recognize sites outside of the supersite and are not dominated by VH1-24 and VH3-30/3–33. Altogether, 16 out of the 43 anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies tested neutralized PMS20 and/or Omicron but not Wuhan-Hu-1. Thus, the B cell memory compartment produced in response to infection with Wuhan-Hu-1 contains antibodies that bind to this strain with high affinity but do not neutralize it and instead neutralize PMS20 and/or Omicron.

Figure 5.

Epitope mapping of anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies reveals six complementation groups

(A) Diagram of the biolayer interferometry experiment.

(B) Biolayer interferometry results presented as a heat-map of relative inhibition of Ab2 binding to the preformed Ab1-NTD complexes (from red to blue, non-competing to competing). Values are normalized through the subtraction of the autologous antibody control. VH gene usage and IC50 values of Wuhan-Hu-1, Gamma, PMS20, and Omicron (heat map, from blue to red, most potent to least potent) for each antibody are shown. The average of two experiments is shown.

Anti-NTD antibodies define neutralizing epitopes outside of the supersite

To delineate the structural basis for broad-recognition of NTD-directed antibodies, we determined structures of WT SARS-CoV-2 S 6P (Hsieh et al., 2020) bound to the fragment antigen-binding (Fab) regions of C1717 (group III), C1520 (group IV), and C1791 (group V) using single-particle cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) (Figure S7; Table S5). Global refinements yielded maps at 2.8 Å (C1520-S), 3.5 Å (C1717-S), and 4.5 Å (C1791-S) resolutions, revealing Fabs bound to NTD epitopes on all three protomers within a trimer irrespective of “up”/”down” RBD conformations for all three Fab-S complexes. C1520 and C1791 Fabs recognize epitopes on opposite faces of the NTD, with binding poses orthogonal to the site i antigenic supersite and distinct from C1717 pose, consistent with BLI mapping data (Figures 5B and S7J). A 4.5 Å resolution structure of antibody C1791 (VH3-23∗01/VK1-17∗01) bound to an S trimer revealed a glycopeptidic NTD epitope wedged between the N61NTD- and N234NTD-glycans, engaging several N-terminal regions including the N1-, N2-, and b8-b9 hairpin loops (Figure S7K). The binding pose of C1791 is similar to the cross-reactive antibody S2L20, which was shown to maintain binding against single NTD mutations and several VOCs but was non-neutralizing (McCallum et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Antibody C1520 (VH3-48∗03/VL4-68∗02) recognizes the NTD beta-sandwich fold, with a distinct pose relative to similar cross-reactive NTD mAbs (Figures 6A–6C) (Cerutti et al., 2021a; McCallum et al., 2021b). The C1520 epitope comprises residues along the supersite beta-hairpin (residues 152–158), the b8-strand (residue 97–102), N4-loop (residues 178–188), and N-linked glycans at positions N122 and N149 (Figure 6D). Targeting of the NTD epitope was driven primarily by heavy chain contacts (the buried surface area [BSA] of NTD epitope on the C1520 HC represented ∼915 Å2 of ∼1,150 Å2 total BSA), mediated by the 20-residue long CDRH3 that contributed 55% of the antibody paratope (Figures 6D and 6E). Previous studies have shown that CDRH3 loops of antibodies targeting this face of the NTD disrupt a conserved binding pocket that accommodates hydrophobic ligands, including polysorbate 80 and biliverdin, which have the potential to prevent binding of supersite antibodies (Cerutti et al., 2021a; Rosa et al., 2021). The 20-residue-long CDRH3 of C1520 displaces the supersite beta-hairpin and N4 loops, which acts as a gate for the hydrophobic pocket (Figure 6F), in a manner similar to antibody P008-056 (Figure 6G). This contrasts Ab5-7 that directly buries the tip of its CDRH3 into the hydrophobic pocket, and S2X303 that maintains a closed gate and partially overlaps with the supersite beta-hairpin (Figure 6G). Thus, C1520’s increased cross-reactivity and neutralization breadth relative to Ab5-7 and S2X303 is likely mediated by displacement of the supersite beta-hairpin and N4-loops, which harbor escape mutations found in several SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and can undergo structural remodeling to escape antibody pressure (Figure 6F) (McCallum et al., 2021b).

Figure 6.

Structures of C1520 binds to the SARS-CoV-2 S 6P ectodomain

(A) 2.8 Å cryo-EM density for C1520-S 6P trimer complex. Inset: 3.1 Å locally refined cryo-EM density for C1520 variable domains (shades of green) bound to NTD (wheat).

(B) Close-up view of C1520 variable domains (green ribbon) binding to NTD (surface rendering, wheat). Site i antigenic supersite is highlighted on NTD for reference (salmon).

(C) Overlay of VH and VL domains of C1520 (green), S2X303 (PDB: 7SOF; powder blue), Ab5-7 (PDB: 7RW2; gold), and P008-056 (PDB: 7NTC; orange) after alignment on NTD residues 27–303, illustrating distinct binding poses to NTD epitopes adjacent to the site i supersite (coral).

(D) Surface rendering of C1520 epitope (green) with CDR loops shown (inset). NTD epitope residues (defined as residues containing atom[s] within 4 Å of a Fab atom) are shown as sticks.

(E) CDRH3-mediated contacts on the NTD. Potential hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines.

(F) Overlay of WT (WA1/2020) NTD (this study) and unliganded Omicron NTD (PDB: 7TB4) with mutations and loop conformational changes highlighted in red.

(G) Comparison of CDRH3 loop position, the NTD supersite beta-hairpin (coral), and NTD N4-loop (orchid) for antibodies shown in (C).

We next investigated the group III antibody, C1717, that showed neutralization breadth against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and distinct binding properties from group IV and V antibodies (Figures 4C, 5B, and S7J). Antibody C1717 (VH1-69∗04/VL1-44∗01) recognizes the viral membrane proximal side of the NTD (Figure 7A), similar to S2M24 (McCallum et al., 2021a), DH1052 (Li et al., 2021), and polyclonal Fabs from donor COV57 (Barnes et al., 2020b). However, C1717’s pose represents an antigenic site that recognizes a glycopeptide epitope flanked by the N282NTD- and N603SD2-glycans and is positioned in closeness, proximity (<12 Å) to the S2-fusion peptide region (Figures 7A and 7B). All six CDR loops contribute to an epitope that spans both the NTD and SD2 regions (residues 600–606) with a S epitope BSA of ∼1325 Å2 (Figure 7B). CDRH1 and CDRH3 loops mediate extensive hydrogen bond and van der Waals contacts with the C terminus of the NTD (residues 286–303) and SD2 loop (residues 600–606), whereas CDRH2 engages N-terminal regions (residues 27–32, 57–60) and NTD loop residues 210–218 (Figure 7C–7F). C1717 light chain CDRL2 and CDRL3 loops contact the C terminus of the NTD (residues 286–303) and the NTD loop 210–218, respectively (Figures 7D and 7E). In addition, light-chain framework region (FWR) 3 buries against the N282NTD-glycan, a complex-type N-glycan (Wang et al., 2021a) that wedges against the SD1 domain of the adjacent protomer (Figures 7A, 7B, and 7D). Modeling of Omicron mutations found in NTD loop 210–218 shows accommodation of the 214-insertion and potential establishment of backbone contacts with the NTD loop and R95LC in CDRL3 (Figure 7F). We speculate that the stabilization of the N282NTD-glycan against the adjacent protomer and the proximity of the C1717 LC to the S2 fusion machinery could potentially contribute to C1717’s neutralization mechanism by preventing access to the S2′ cleavage site or destabilization of S1. Such a mechanism could explain the lack of Delta neutralization, as this variant has been shown to have enhanced cell-cell fusion activity relative to all other variants of concern (McCallum et al., 2021b; Zhang et al., 2021). However, future experiments to test this hypothesis are needed.

Figure 7.

Structure of C1717 reveals an antigenic site situated in closeness, proximity to S2 fusion machinery

(A) 3.5 Å cryo-EM density for C1717-S 6P trimer complex. Inset: C1717 variable domains (shades of purple) binding to an S1 protomer (surface rendering). The fusion peptide (FP, red) in the S2 domain is shown.

(B) Surface rendering of C1717 epitope (thistle) with C1717 CDR loops shown as ribbon.

(C–E) Residue-level contacts between the SARS-CoV-2 S NTD (wheat) and the SD2 domains (gray) with (C) C1717 CDRH1 and CDRH3 loops, (D) CDRL2 loop, (E) CDRL3 and CDRH2 loops. In all panels C1717 residues are colored purple.

(F) Residue-level contacts between C1717 (purple) and NTD (wheat) as shown in (E). Modeled Omicron mutations in the N5 loop are shown as red spheres.

Discussion

In animal models, passive antibody infusion early in the course of infection accelerates viral clearance and protects against disease (Hansen et al., 2020; Hassan et al., 2020; McMahan et al., 2021; Rogers et al., 2020; Schmitz et al., 2021; Tortorici et al., 2020; Zost et al., 2020a). In humans, rapid development of neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 is associated with better clinical outcomes (Khoury et al., 2021). Although there was initial concern that antibodies might enhance disease, and some NTD antibodies were found to enhance infection in vitro, they were protective in vivo (Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021). Finally, early passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies to high-risk individuals alters the course of the infection and can prevent hospitalization and death (Dougan et al., 2021; Gupta et al., 2021; Weinreich et al., 2021). Thus, antibodies play an essential role in both protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and serious disease.

The RBD and the NTD are the two dominant targets of neutralizing antibodies on the SARS-CoV-2 S protein. When the memory B cell compartment is probed using intact S, the majority of the neutralizing antibodies obtained target the RBD and only a small number that are usually less potent or broad target the NTD (Kreer et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Zost et al., 2020b). Consistent with previous reports, many of the mAbs isolated that target the most solvent-accessible surfaces of the NTD are non-neutralizing (Amanat et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020, 2021; McCallum et al., 2021a, 2021b). Among the neutralizers that recognize the NTD, the majority target the site i supersite, and these antibodies are enriched in IGVH3-33 and IGVH1-24 (Amanat et al., 2021; Cerutti et al., 2021b; Chi et al., 2020; Dussupt et al., 2021; Haslwanter et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021a; Planas et al., 2021b; Suryadevara et al., 2021b; Voss et al., 2021). The few existing exceptions target a region orthogonal to the supersite featuring a pocket that accommodates hydrophobic ligands, such as polysorbate 80 and biliverdin (Cerutti et al., 2021a; Rosa et al., 2021). Focusing on the NTD and using complementary probes revealed six partially overlapping complementary groups of NTD neutralizing antibodies.

Groups I and II are partially overlapping and appear to target the supersite on the target cell facing surface of the NTD. Group I is enriched in IGVH3-33 and IGVH3-30, while group II is enriched in IGVH1-24. Together, these two groups make up 42% of all the neutralizers characterized, none of which are broad or able to neutralize Omicron or PMS20 that carry extensive site i supersite mutations. Groups I and II differ in their ability to inhibit each other’s binding to the NTD likely because they assume different binding poses. Group III is enriched in IGVH4-39 and is unusual in that all the antibodies in this group neutralize the synthetic PMS20 variant, but only 24% neutralize Gamma, and only 1 of 18 tested is broad. The antibodies in this group target a site of neutralization on the membrane proximal side of the NTD, bridging the SD2 domain on the same protomer, and potentially infringe on the S2 domain to impede S function in viral-host membrane fusion (Suryadevara et al., 2021a). Groups IV, V, and VI comprise only 19% of all the NTD neutralizers tested but are highly enriched in the broad neutralizers, which have the potential to provide universal protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants infection. Group IV and V antibodies target opposite sides of the NTD orthogonal to the site i supersite, recognizing epitopes that are non- or only partially overlapping with variant-of-concern mutations and are not significantly impacted by conformational changes in the supersite beta-hairpin (McCallum et al., 2021b). While structurally unique in their binding pose, group IV and V antibodies likely fail to inhibit ACE2 interactions, suggesting a potent neutralization mechanism that stabilizes the prefusion S glycoprotein. Such mechanisms have been suggested for similar NTD-directed antibodies (Cerutti et al., 2021a; McCallum et al., 2021a; Suryadevara et al., 2021b) and remain to be explored.

Although a great number of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies have been identified, Omicron escapes the majority, including most antibodies in clinical use (Cameroni et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2021; Planas et al., 2021a). There is an urgent need to identify broad neutralizers that recognize epitopes that are conserved among SARS-CoV-2 variants, especially those that are heavily mutated, like PMS20 and Omicron. The conserved epitopes would be ideal targets for future development of broadly active sarbecovirus vaccines and antibody drugs to overcome antigenic drift.

Immune responses selectively expand two independent groups of B lymphocytes, plasma cells, and memory B cells. Plasma cells are end-stage cells that are selected based on affinity. They are home to the bone marrow where they reside for variable periods of time and secrete specific antibodies found in plasma. An initial contraction in the number of these cells in the first 6 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination likely accounts for the decrease in plasma neutralizing activity and subsequent loss of protection from infection (Cho et al., 2021; Gaebler et al., 2021).

Memory cells are found in circulation and in lymphoid organs where they are relatively quiescent. B cells selected into this compartment are far more diverse than those that become plasma cells and include cells with somatically mutated receptors that have variable affinities for the immunogen (Viant et al., 2020, 2021). This includes cells producing antibodies with relatively high affinities that are highly specific for the antigen as well as cells producing antibodies with affinity for the initial immunogen and the ability to bind to closely related antigens. Production of a pool of long lived but quiescent memory cells expressing a diverse collection of closely related antibodies, some of which can recognize pathogen variants, favors rapid secondary responses upon SARS-CoV-2 variant exposure in pre-exposed and vaccinated individuals.

Both RBD- and NTD-specific memory B cells continue to evolve, as evidenced by increasing levels of somatic hypermutations and emergence of clones found at single timepoint (Wang et al., 2021b). However, NTD-elicited memory monoclonal antibodies show more modest neutralizing potency than those that are elicited by RBD (Wang et al., 2021b). There are innumerable differences between NTD protein and RBD protein that could account for these differences. These include, but are not limited to, (1) the physical nature of the antigen (Zhang et al., 2021), (2) different neutralizing mechanisms, and (3) mutations in NTD that lead to conformational remodeling.

SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination with Wuhan-Hu-1 produces plasma antibody responses that are relatively specific for Wuhan-Hu-1 and are sub-optimally protective against infection with variant strains such as Omicron. In contrast, memory B cell populations produced in response to infection or vaccination are sufficiently diversified to contain high-affinity antibodies that can potently neutralize numerous different variants including Omicron. This diverse collection of memory cells and their cognate memory T cells are likely to make a major contribution to the generally milder course of infection in individuals that have been infected and/or vaccinated with SARS-CoV-2.

Limitations of the study

This study has the following limitations. First, the cohort is limited in size and does not include infection naive individuals that received mRNA or vector-based vaccines or breakthrough infections. Second, whether the neutralizing antibodies isolated from this study are protective or therapeutic has not been determined.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-CD20-PECy7 | BD Biosciences | Cat#335811; RRID:AB_399985 |

| anti-CD3-APC-eFluro 780 | Invitrogen | Cat# 47-0037-41; RRID:AB_2573935 |

| anti-CD8-APC-eFluor 780 | Invitrogen | Cat# 47-0086-42; RRID:AB_2573945 |

| anti-CD16-APC-eFluor 780 | Invitrogen | Cat# 47-0168-41; RRID:AB_11219083 |

| anti-CD14-APC-eFluor 780 | Invitrogen | Cat# 47-0149-42; RRID:AB_1834358 |

| Zombie NIR | BioLegend | Cat# 423105 |

| anti-human IgG HRP | Jackson Immuno Research | Cat# 109-036-088; RRID:AB_2337594 |

| anti-human IgM HRP | Jackson Immuno Research | Cat# 109-035-129; RRID:AB_2337588 |

| anti-human IgA HRP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A0295; RRID:AB_257876 |

| anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibody | GeneTex | Cat# GTX135357; RRID:AB_2868464 |

| goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 | Life Technologies | Cat# A-11012; RRID:AB_2534079 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 USA-WA1/2020 | BEI Resources | Cat# NR-52281 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant | BEI Resources | Cat# NR-54008 |

| Biological samples | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 convalescent human subjects | Robbiani et al. (2020); Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03696-9 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | GIBCO | Cat#11995-065 |

| FCS | Sigma | Cat#F0926 |

| Polyethylenimine | Polysciences | Cat#23966-1; CAS: 9002-98-6, 26913-06-4 |

| Gentamicin solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#G1397. CAS:1405-41-0 |

| Blasticidin S HCl | GIBCO | Cat#A1113902; CAS: 3513-03-9 |

| Expi293 Expression medium | GIBCO | Cat#A1435101 |

| Tween-20 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P1379 |

| TMB Substrates | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#34021 |

| Opti-MEM | GIBCO | Cat#31985070 |

| TRIzol Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#15596026 |

| Triton X-100 | Thermo Scientific | Cat#HFH10 |

| Hoechst 33342 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#62249 |

| Ovalbumin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A5503-1G |

| Streptavidin-BV711 | BD biosciences | Cat#563262 |

| Streptavidin-PE | BD biosciences | Cat#554061 |

| Streptavidin-AF647 | BD biosciences | Cat#405237 |

| RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitors | Promega | Cat# N2615 |

| SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase | Invitrogen | Cat#18080-044 |

| Wuhan-Hu-1 NTD | This manuscript | N/A |

| Gamma NTD | This manuscript | N/A |

| Delta NTD | This manuscript | N/A |

| Omicron NTD | This manuscript | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis 5× Reagent | Promega | Cat#E1531 |

| Protein A biosensor | ForteBio | Cat#18-5010 |

| Bio-Layer Interferometer | ForteBio | Octet RED96e |

| ImageXpress Micro XLS | Molecular Devices | The ImageXpress Micro 4 |

| Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat#N1110 |

| ELISA microplate reader | FluoStar Omega | BMG Labtech |

| RNeasy Mini Kit column | QIAGEN | Cat# 74014 |

| EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotinylation kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Car# 21435 |

| Quantifoil grid | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Q3100AR1.3 |

| fluorinated octyl-maltoside | Anatrace | Cat# O310F |

| Mark IV Vitrobot | Thermo Fisher Scientific | https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/MSD/Datasheets/Thermo-Scientific-Vitrobot-Datasheet.pdf |

| Deposited data | ||

| Antibody sequences | Zenodo | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.6380908 |

| C1520 Fab – SARS-CoV-2 S 6P (global) | This manuscript | PDB: 7UAP EMDB: 26429 |

| C1520 Fab – SARS-CoV-2 S 6P NTD (local refinement) | This manuscript | PDB: 7UAQ EMDB: 26430 |

| C1717 Fab – SARS-CoV-2 S 6P | This manuscript | PDB: 7UAR EMDB: 26431 |

| C1791 Fab – SARS-CoV-2 S 6P | This manuscript | EMDB: 26432 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| 293T cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| 293TAce2 cells | Robbiani et al. (2020) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9 |

| HT1080Ace2 cells cl.14 | Schmidt et al. (2020) | https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201181 |

| VeroE6 cells | ATCC | Cat#CRL-1586 |

| Caco-2 cells | ATCC | Cat#HTB-37 |

| Expi293F cells | GIBCO | Cat#A14527 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Human immunoglobulin (Ig) genes primer | Robbiani et al. (2020) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pNL4-3DEnv-nanoluc | Robbiani et al. (2020) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9 |

| pCR3.1_GA_S2_Wuhan-Hu-1 (pSARS-CoV2-Strunc |

Robbiani et al. (2020) Schmidt et al. (2020) |

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9 https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201181 |

| pCR3.1_GA_S2_R683G (pSARS-CoV2-S-SΔ19(R683G)) | Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.15.426911 |

| PMS20 spike | Schmidt et al. (2021a, 2021b) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04005-0 |

| pCR3.1 SARS-CoV SΔ19 | Schmidt et al., (2020) | https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201181 |

| pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G)_Alpha | Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03696-9 |

| pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G)_Beta | Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03696-9 |

| pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G)_Gamma | Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03696-9 |

| pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G)_Delta | Cho et al. (2021) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04060-7 |

| pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G)_Iota | Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03696-9 |

| pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G)_Omicron BA.1 | Schmidt et al. (2021a) | https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2119641 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism 8 or V9.1 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/; RRID: SCR_002798 |

| Geneious Prime Version 2020.1.2 |

https://www.geneious.com/ | RRID:SCR_010519 |

| Python programming language version 3.7 | https://www.python.org/ | RRID:SCR_008394 |

| Omega MARS software | Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.07.443175 |

| ForteBio | Wang et al. (2021a, 2021b, 2021c) | https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.07.443175 |

| Macvector 18.2.2 | MacVector Assembler | https://macvector.com/Assembler/assembler.html |

| Titan Krios transmission electron microscope | Thermo Fisher Scientific | https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/electron-microscopy/products/transmission-electron-microscopes/krios-g4-cryo-tem.html |

| SerialEM 3.7 | Mastronarde (2005) |

https://bio3d.colorado.edu/SerialEM/ RRID:SCR_017293 |

| cryoSPARC 2.14 and 2.15 | Punjani et al. (2017) |

https://www.cryosparc.com RRID:SCR_016501 |

| UCSF Chimera |

Pettersen et al. (2004) Goddard et al. (2007) |

http://plato.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ RRID:SCR_004097 |

| Phenix | Adams et al. (2010) |

https://www.phenix-online.org/ RRID:SCR_014224 |

| Coot | Emsley et al. (2010) |

https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ RRID:SCR_014222 |

| MolProbity | Chen et al. (2010) |

http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu RRID:SCR_014226 |

| Other | ||

| HisTrap FF | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Cat# 17-5255-01 |

| HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Cat# 28-9893-35 |

| Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Cat# 29-0915-96 |

| HiTrap MabSelect SuRe column, 5 mL | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Cat# 11-0034-95 |

| Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Cat# 28-9909-44 |

| Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Devices | Millipore | Cat# UFC903096 |

| 300 Mesh Pure C carbon-coated copper grids | EM Sciences | Cat# Q350AR13A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Requests for further information and or reagents should be addressed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact Michel Nussenzweig: nussen@rockefeller.edu.

Materials availability

All expression plasmids generated in this study for CoV proteins, CoV pseudoviruses, human Fabs and IgGs are available upon request through a Materials Transfer Agreement (MTA).

Experimental model and subject details

Samples were obtained from 62 individuals under a study protocol approved by the Rockefeller University in New York from February 8, 2020 to March 26, 2021. Eligible participants were adults with a history of participation in both prior study visits of our longitudinal cohort study of COVID-19 recovered individuals(Gaebler et al., 2021; Robbiani et al., 2020). All participants had a confirmed history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, either diagnosed during the acute infection by RT-PCR or retrospectively confirmed by seroconversion. Exclusion criteria included presence of symptoms suggestive of active SARS-CoV-2 infection. Study participants who had received COVID-19 vaccinations, were exclusively recipients of one of the two currently EUA-approved mRNA vaccines, Moderna (mRNA-1273) or Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2), and individuals who received both doses did so according to current interval guidelines, namely 28 days (range 28–30 days) for Moderna and 21 days (range 21–23 days) for Pfizer-BioNtech. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in the study, and the study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice. For detailed participant characteristics see Table S1.

Cell lines

293T cells (Homo sapiens; sex: female, embryonic kidney) obtained from the ATCC (CRL-3216) and HT1080Ace2 cl14 cells (parental HT1080: homo sapiens; sex: male, fibrosarcoma) (Schmidt et al., 2020) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C and 5% CO2. VeroE6 cells (Chlorocebus sabaeus; sex: female, kidney epithelial) obtained from the ATCC (CRL-1586™) and from Ralph Baric (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), and Caco-2 cells (Homo sapiens; sex: male, colon epithelial) obtained from the ATCC (HTB-37™) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1% nonessential amino acids (NEAA) and 10% FBS at 37°C and 5% CO2. Expi293F cells (GIBCO) for protein expression were maintained at 37°C and 8% CO2 in Expi293 Expression medium (GIBCO), transfected using Expi293 Expression System Kit (GIBCO) and maintained under shaking at 130 rpm. All cell lines have been tested negative for contamination with mycoplasma.

Viruses

SARS-CoV-2 strains USA-WA1/2020 and the South African beta variant B.1.351 were obtained from BEI Resources (catalog no. NR-52281 and NR-54008, respectively).

Method details

Blood samples processing and storage

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) obtained from samples collected at Rockefeller University were purified by gradient centrifugation and stored in liquid nitrogen in the presence of FCS and DMSO. Heparinized plasma and serum samples were aliquoted and stored at −20°C or less. Prior to experiments, aliquots of plasma samples were heat-inactivated (56°C for 1 h) and then stored at 4°C.

ELISAs

ELISAs(Amanat et al., 2020; Grifoni et al., 2020) to evaluate antibodies binding to SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1-, Delta-, Gamma and Omicron-NTD were performed by coating of high-binding 96-half-well plates (Corning 3690) with 50 μL per well of a 1 μg/mL protein solution in PBS overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed 6 times with washing buffer (1× PBS with 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich)) and incubated with 170 μL per well blocking buffer (1× PBS with 2% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma)) for 1 h at room temperature. Immediately after blocking, monoclonal antibodies or plasma samples were added in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Plasma samples were assayed at a 1:66 starting dilution and 7 additional threefold serial dilutions. Monoclonal antibodies were tested at 10 μg/mL starting concentration and 10 additional fourfold serial dilutions. Plates were washed 6 times with washing buffer and then incubated with anti-human IgG, IgM or IgA secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Jackson Immuno Research 109-036-088 109-035-129 and Sigma A0295) in blocking buffer at a 1:5,000 dilution (IgM and IgG) or 1:3,000 dilution (IgA). Plates were developed by addition of the HRP substrate, TMB (ThermoFisher) for 10 min (plasma samples) or 4 min (monoclonal antibodies), then the developing reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL 1 M H2SO4 and absorbance was measured at 450 nm with an ELISA microplate reader (FluoStar Omega, BMG Labtech) with Omega and Omega MARS software for analysis(Wang et al., 2021b). For plasma samples, a positive control (plasma from participant COV57, diluted 66.6-fold and seven additional threefold serial dilutions in PBS) was added to every assay plate for validation. The average of its signal was used for normalization of all of the other values on the same plate with Excel software before calculating the area under the curve using Prism V9.1(GraphPad). For monoclonal antibodies, the EC50 was determined using four-parameter nonlinear regression (GraphPad Prism V9.1).

Expression of NTD proteins

Mammalian expression vectors encoding the SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1- NTD (GenBank MN985325.1; S protein residues 14–307), or Delta, Gamma and Omicron NTD mutants with an N-terminal human IL-2 or Mu phosphatase signal peptide and a C-terminal polyhistidine tag followed by an AviTag were used to express soluble NTD proteins by transiently-transfecting Expi293F cells (GIBCO). After four days, NTD proteins were purified from the supernatants by nickel affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. Peak fractions were identified by SDS-PAGE, and fractions corresponding to monomeric NTDs were pooled and stored at 4°C.

SARS-CoV-2 and sarbecovirus spike protein pseudotyped reporter virus

Plasmids pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G) and pSARS-CoV-SΔ19 expressing C-terminally truncated SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV spike proteins and the polymutant PMS20 spike were as described before (Schmidt et al., 2021b). A panel of plasmids expressing spike proteins from SARS-CoV-2 variants were based on pSARS-CoV-2-SΔ19(R683G) and contain the following substitutions/deletions: Alpha (B.1.1.7): ΔH69/V70, ΔY144, N501Y, A470D, D614G, P681H, T761I, S982A, D118H; Beta (B.1.351): D80A, D215G, L242H, R246I, K417N, E484K, N501Y, D614G, A701V; Gamma (P.1): L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, E484K, N501Y, D614G, H655Y, T1027I, V1167F; Delta (B.1.617.2): T19R, Δ156–158, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N; Iota (B.1.526): L5F, T95I, D253G, E484K, D614G, A701V (Cho et al., 2021); Omicron (B.1.1.529) 8: A67V, Δ69–70, T95I, G142D, Δ143-145, Δ211, L212I, ins214EPE, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493K, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, H679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969H, N969K, L981F. All SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins including variants and the polymutant spike protein PMS20 included the R683G substitution, which disrupts the furin cleavage site and generates higher titer virus stocks without significant effects on pseudotyped virus neutralization sensitivity (Schmidt et al., 2021b). An env-inactivated HIV-1 reporter construct (pNL4-3ΔEnv-nanoluc) was generated from pNL4-332 by introducing a 940-bp deletion 3′ in the vpu stop codon, resulting in a frameshift in env. The human codon-optimized nanoluc Luciferase reporter gene (Nluc, Promega) was inserted in place of nucleotides 1–100 of the nef gene. To generate pseudotyped viral stocks, 293T cells were transfected with pNL4-3ΔEnv-nanoluc and pSARS-CoV-2-Strunc using polyethylenimine. Co-transfection of pNL4-3ΔEnv-nanoluc and S-expression plasmids leads to production of HIV-1-based virions that carried either the SARS-CoV-2 S protein on the surface. After transfection for 8 h, cells were washed twice with PBS and fresh medium was added. Supernatants containing virions were collected 48 h after transfection, filtered and stored at −80 °C (Cho et al., 2021; Robbiani et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021b).

Pseudotyped virus neutralization assay

Monoclonal antibodies were initially screened at a at a concentration of 1000 ng/mL to identify those that show >40% neutralization at this concentration. Antibodies were incubated with SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1(Robbiani et al., 2020) or SARS-CoV pseudotyped virus for 1 h at 37°C. The mixture was subsequently incubated with HT1080Ace2 cl14 cells (Schmidt et al., 2020) for 48 h after which cells were washed with PBS and lysed with Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis 5× reagent (Promega). Nanoluc Luciferase activity in lysates was measured using the Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) with the Glomax Navigator (Promega). The obtained relative luminescence units were normalized to those derived from cells infected with pseudotyped virus in the absence of monoclonal antibodies. Antibodies that showed >40% neutralization at a concentration of 1000 ng/mL were subjected to further titration experiments to determine their IC50s. Antibodies were 4-fold serially diluted and tested against pseudoviruses as detailed above. IC50s were determined using four-parameter nonlinear regression (least squares regression method without weighting; constraints: top = 1, bottom = 0) (GraphPad Prism).

Virus titration

The original WT virus was amplified in Caco-2 cells, which were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.05 plaque forming units (PFU)/cell and incubated for 6 days at 37°C. The B.1.351 variant was amplified in VeroE6 cells obtained from the ATCC that were engineered to stably express TMPRSS2 (VeroE6TMPRSS2). VeroE6TMPRSS2 cells were infected at a MOI = 0.1 PFU/cell and incubated for 4 days at 33°C. Virus-containing supernatants were subsequently harvested, clarified by centrifugation (3,000 g × 10 min), filtered using a disposable vacuum filter system with a 0.22 μm membrane and stored at −80°C. Virus stock titers were measured by standard plaque assay (PA) on VeroE6 cells obtained from Ralph Baric (referred to as VeroE6UNC). Briefly, 500 μL of serial 10-fold virus dilutions in Opti-MEM were used to infect 4 × 105 cells seeded the day prior into wells of a 6-well plate. After 1.5 h adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed, and cells were overlayed with DMEM containing 10% FBS with 1.2% microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel). Cells were incubated for 4 days at 33°C, followed by fixation with 7% formaldehyde and crystal violet staining for plaque enumeration. All SARS-CoV-2 experiments were performed in a biosafety level 3 laboratory.

To confirm virus identity and evaluate for unwanted mutations that were acquired during the amplification process, RNA from virus stocks was purified using TRIzol Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog no. 15596026). Brief, 200 μL of each virus stock was added to 800 μL TRIzol Reagent, followed by 200 μL chloroform, which was then centrifuged at 12,000 g × 5 min. The upper aqueous phase was moved to a new tube, mixed with an equal volume of isopropanol, and then added to a RNeasy Mini Kit column (QIAGEN, catalog no. 74014) to be further purified following the manufacturer’s instructions. Viral stocks were subsequently confirmed via next generation sequencing using libraries for Illumina MiSeq.

Microscopy-based authentic SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay

The day prior to infection VeroE6UNC cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well into 96-well plates. Antibodies were serially diluted (4-fold) in cell culture medium, consisting of medium 199 (Lonza, Inc.) supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1× penicillin/streptomycin. Next, the diluted samples were mixed with a constant amount of SARS-CoV-2 and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The antibody-virus-mix was then directly applied to each well (n = 3 per dilution) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The infectious dose for each virus was pre-determined on VeroE6UNC cells to yield 50–60% antigen-positive cells upon this incubation period (USA-WA1/2020: 1,250 PFU/well and B.1.351: 175 PFU/well). Cells were subsequently fixed by adding an equal volume of 7% formaldehyde to the wells, followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After extensive washing, cells were incubated for 1h at RT with blocking solution of 5% goat serum in PBS (Jackson ImmunoResearch, catalog no. 005–000-121). A rabbit polyclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibody (GeneTex, catalog no. GTX135357) was added to the cells at 1:1,000 dilution in blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C. Next, goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 594 (Life Technologies, catalog no. A-11012) was used as a secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:2,000 and incubated overnight at 4°C. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog no. 62249) at a 1 μg/mL. Images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope and analyzed using ImageXpress Micro XLS (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All statistical analyses were done using Prism 8 software (Graphpad).

Biotinylation of viral protein for use in flow cytometry

Purified and Avi-tagged SARS-CoV-2 NTD was biotinylated using the Biotin-Protein Ligase-BIRA kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Avidity) as described before (Robbiani et al., 2020). Ovalbumin (Sigma, A5503-1G) was biotinylated using the EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotinylation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific). Biotinylated ovalbumin was conjugated to streptavidin-BV711 (BD biosciences, 563262), Gamma NTD to streptavidin-PE (BD Biosciences, 554061) and Wuhan-Hu-1 NTD to streptavidin-AF647 (Biolegend, 405237).

Flow cytometry and single cell sorting

Single cell sorting by flow cytometry was performed as described (Robbiani et al., 2020). Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were enriched for B cells by negative selection using a pan-B-cell isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-101-638). The enriched B cells were incubated in FACS buffer (1× PBS, 2% FCS, 1 mM EDTA) with the following anti-human antibodies (all at 1:200 dilution): anti-CD20-PECy7 (BD Biosciences, 335793), anti-CD3-APC-eFluro 780 (Invitrogen, 47-0037-41), anti-CD8-APC-eFluor 780 (Invitrogen, 47-0086-42), anti-CD16-APC-eFluor 780 (Invitrogen, 47-0168-41), anti-CD14-APC-eFluor 780 (Invitrogen, 47-0149-42), as well as Zombie NIR (BioLegend, 423105) and fluorophore-labelled RBD and ovalbumin (Ova) for 30 min on ice. Single CD3−CD8−CD14−CD16−CD20+Ova−Gamma NTD-PE+Wuhan-Hu-1 NTD-AF647+ B cells were sorted into individual wells of 96-well plates containing 4 μL of lysis buffer (0.5× PBS, 10 mM DTT, 3,000 units/mL RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitors (Promega, N2615) per well using a FACS Aria III and FACSDiva software (Becton Dickinson) for acquisition and FlowJo for analysis. The sorted cells were frozen on dry ice, and then stored at −80 °C or immediately used for subsequent RNA reverse transcription.

Antibody sequencing, cloning and expression

Antibodies were identified and sequenced as described previously (Robbiani et al., 2020). In brief, RNA from single cells was reverse-transcribed (SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase, Invitrogen, 18080-044) and the cDNA stored at −20 °C or used for subsequent amplification of the variable IGH, IGL and IGK genes by nested PCR and Sanger sequencing. Sequence analysis was performed using MacVector. Amplicons from the first PCR reaction were used as templates for sequence- and ligation-independent cloning into antibody expression vectors. Recombinant monoclonal antibodies and Fabs were produced and purified as previously described (Robbiani et al., 2020).

Biolayer interferometry

BLI assays were performed on the Octet Red instrument (ForteBio) at 30 °C with shaking at 1,000 r.p.m. Epitope binding assays were performed with protein A biosensor (ForteBio 18–5010), following the manufacturer’s protocol “classical sandwich assay” as follows: (1) Sensor check: sensors immersed 30 s in buffer alone (buffer ForteBio 18–1105), (2) Capture 1st Ab: sensors immersed 10 min with Ab1 at 10 μg/mL, (3) Baseline: sensors immersed 30 s in buffer alone, (4) Blocking: sensors immersed 5 min with IgG isotype control at 10 μg/mL. (5) Baseline: sensors immersed 30 s in buffer alone, (6) Antigen association: sensors immersed 5 min with NTD at 10 μg/mL. (7) Baseline: sensors immersed 30 s in buffer alone. (8) Association Ab2: sensors immersed 5 min with Ab2 at 10 μg/mL. Curve fitting was performed using the Fortebio Octet Data analysis software (ForteBio). Affinity measurement of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgGs binding were corrected by subtracting the signal obtained from traces performed with IgGs in the absence of WT NTD. The kinetic analysis using protein A biosensor (ForteBio 18–5010) was performed as follows: (1) baseline: 60s immersion in buffer. (2) loading: 200s immersion in a solution with IgGs 10 μg/mL (3) baseline: 200s immersion in buffer. (4) Association: 300s immersion in solution with WT NTD at 200, 100, 50 or 25 μg/mL (5) dissociation: 600s immersion in buffer. Curve fitting was performed using a fast 1:1 binding model and the Data analysis software (ForteBio). Mean K D values were determined by averaging all binding curves that matched the theoretical fit with an R2 value ≥ 0.8.

Recombinant protein expression for structural studies

Expression and purification of stabilized SARS-CoV-2 6P ectodomain was conducted as previously described (Barnes et al., 2020a). Briefly, constructs encoding the SARS-CoV-2 S ectodomain (residues 16–1206 with 6P stabilizing mutations (Hsieh et al., 2020), a mutated furin cleavage site, and C-terminal foldon trimerization motif followed by hexa-His tag) were used to transiently transfect Expi293F cells (Gibco). Four days after transfection, supernatants were harvested and S 6P proteins were purified by nickel affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. Peak fractions from size-exclusion chromatography were identified by SDS-PAGE, and fractions corresponding to spike trimers were pooled and stored at 4°C. Fabs and IgGs were expressed, purified, and stored as previously described (Barnes et al., 2020a).

Cryo-EM sample preparation

Purified Fabs were mixed with SARS-CoV-2 S 6P trimer at a 1.1:1 M ratio of Fab-to-protomer for 30 min at room temperature. Fab-S complexes were concentrated to 3–4 mg/mL prior to deposition on a freshly glow-discharged 300 mesh, 1.2/1.3 Quantifoil grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Immediately prior to deposition of 3 μL of complex onto grid, fluorinated octyl-maltoside (Anatrace) was added to the sample to a final concentration of 0.02% w/v. Samples were vitrified in 100% liquid ethane using a Mark IV Vitrobot (Thermo Fisher) after blotting at 22°C and 100% humidity for 3s with Whatman No. 1 filter paper.

Cryo-EM data collection and processing

Single-particle cryo-EM data were collected on a Titan Krios transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher) equipped with a Gatan K3 direct detector, operating at 300 kV and controlled using SerialEM automated data collection software (Mastronarde, 2005). A total dose of ∼60 e−/Å2 was accumulated on each movie comprising 40 frames with a pixel size of 0.515 Å (C1520-S dataset) or 0.852 Å (C1717-S and C1791-S) and a defocus range of −1.0 and −2.5 μm. Further data collection parameters are summarized in Table S5.

Movie frame alignment, CTF estimation, particle-picking and extraction were carried out using cryoSPARC v3.1 (Punjani et al., 2017). Reference-free particle picking and extraction were performed on dose-weighted micrographs curated to remove images with poor CTF fits or signs of crystalline ice. A subset of 4x-downsampled particles were used to generate ab initio models, which were then used for heterogeneous refinement of the entire dataset in cryoSPARC. Particles belonging to classes that resembled Fab-S structures were extracted, downsampled x2 and subjected to 2D classification to select well-defined particle images. 3D classifications (k = 6, tau_fudge = 4) were carried out using Relion v3.1.1 (Fernandez-Leiro and Scheres, 2017) without imposing symmetry and a soft mask. Particles corresponding to selected classes were re-extracted without binning and 3D refinements were carried out using non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. Particle stacks were split into individual exposure groups based on the beamtilt angle used for data collection and subjected to per particle CTF refinement and aberration corrections. Another round of non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC was then performed. For focused classification and local refinements of the Fab VHVL-NTD interface, particles were 3D classified in Relion without alignment using a mask that encompassed the Fab-NTD region. Particles in good 3D classes were then used for local refinement in cryoSPARC. Details of overall resolution and locally-refined resolutions according to the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation of 0.143 criterion (Bell et al., 2016) can be found in Table S5.

Cryo-EM structure modeling, refinement, and analyses

Coordinates for initial complexes were generated by docking individual chains from reference structures (see Table S5) into cryo-EM density using UCSF Chimera (Goddard et al., 2007; Pettersen et al., 2004). Initial models for Fabs were generated from coordinates from PDB 6RCO (for C1717 Fab) or PDB 7RKS (for C1520). Models were refined using one round of rigid body refinement followed by real space refinement in Phenix (Adams et al., 2010). Sequence-updated models were built manually in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and then refined using iterative rounds of refinement in Coot and Phenix. Glycans were modeled at potential N-linked glycosylation sites (PNGSs) in Coot. Validation of model coordinates was performed using MolProbity(Chen et al., 2010).

Structure figures were made with UCSF ChimeraX (Goddard et al., 2018). Local resolution maps were calculated using cryoSPARC v3.1(Punjani et al., 2017). Buried surface areas were calculated using PDBePISA (Krissinel and Henrick, 2007) and a 1.4 Å probe. Potential hydrogen bonds were assigned as interactions that were <4.0 Å and with A-D-H angle >90°. Potential van der Waals interactions between atoms were assigned as interactions that were <4.0 Å. Hydrogen bond and van der Waals interaction assignments are tentative due to resolution limitations. Spike epitope residues were defined as residues containing atom(s) within 4 Å of a Fab atom for the C1520-S and C1717-S complexes, and defined as spike Cα atom within 7 Å of a Fab Cα atom for the C1791-S complex.

Computational analyses of antibody sequences

Antibody sequences were trimmed based on quality and annotated using Igblastn v.1.14. with IMGT domain delineation system. Annotation was performed systematically using Change-O toolkit v.0.4.540 (Gupta et al., 2015). Heavy and light chains derived from the same cell were paired, and clonotypes were assigned based on their V and J genes using in-house R and Perl scripts (Figure S3). All scripts and the data used to process antibody sequences are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/stratust/igpipeline/tree/igpipeline2_timepoint_v2).

The frequency distributions of human V genes in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies from this study was compared to 131,284,220 IgH and IgL sequences generated by (Soto et al., 2019) and downloaded from cAb-Rep (Guo et al., 2019), a database of human shared BCR clonotypes available at https://cab-rep.c2b2.columbia.edu/. Based on the 174 distinct V genes that make up the 3085 analyzed sequences from Ig repertoire of the 6 participants present in this study, we selected the IgH and IgL sequences from the database that are partially coded by the same V genes and counted them according to the constant region. The frequencies shown in (Figures 3D and S4) are relative to the source and isotype analyzed. We used the two-sided binomial test to check whether the number of sequences belonging to a specific IgHV or IgLV gene in the repertoire is different according to the frequency of the same IgV gene in the database. Adjusted p values were calculated using the false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Significant differences are denoted with stars.

Nucleotide somatic hypermutation and CDR3 length were determined using in-house R and Perl scripts. For somatic hypermutations, IGHV and IGLV nucleotide sequences were aligned against their closest germlines using Igblastn and the number of differences were considered nucleotide mutations. The average mutations for V genes were calculated by dividing the sum of all nucleotide mutations across all participants by the number of sequences used for the analysis. To calculate the GRAVY scores of hydrophobicity (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982) we used Guy H.R. Hydrophobicity scale based on free energy of transfer (kcal/mole) (Guy, 1985) implemented by the R package Peptides (the Comprehensive R Archive Network repository; https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2015/RJ-2015-001/RJ-2015-001.pdf). We used heavy chain CDR3 amino acid sequences from this study and 22,654,256 IGH CDR3 sequences from the public database of memory B cell receptor sequences (DeWitt et al., 2016). The two-tailed Wilcoxon nonparametric test was used to test whether there is a difference in hydrophobicity distribution.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Numbers of replicates and experiments and statistical tests for each experiment are indicated in in the respective figure legends. For statistical analysis, data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests, two tailed-Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests, two-sided Kruskal Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons, Fisher exact test, four-parameter nonlinear regression (least-squares regression method without weighting) were used for statistical analysis as indicated in figure legends. Unless otherwise indicated, the data in figures were displayed as the Geometric mean.

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants who devoted time to our research, The Rockefeller University Hospital nursing staff, and Clinical Research Support Office. Thanks to all members of the M.C.N. laboratory for helpful discussions, Maša Jankovic for laboratory support, and Kristie Gordon for technical assistance with cell-sorting experiments. We thank the laboratory of Dr. Pamela Bjorkman at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) for SARS-CoV-2 spike expression constructs. We thank Dr. Jost Vielmetter and other members of the Protein Expression Center in the Beckman Institute at Caltech for expression assistance. Cryo-EM data for this work was collected at the Stanford-SLAC cryo-EM center with support from Dr. Elizabeth Montabana and the Evelyn Gruss Lipper cryo-EM resource center (Rockefeller University) with support from Mark Ebrahim, Johanna Sotiris, and Honkit Ng. This work was supported by NIH grants P01-AI138398-S1 and 2U19AI111825 to M.C.N., R37-AI64003 to P.D.B., and R01AI78788 to T.H. C.O.B. is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Hanna Gray Fellowship and is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub investigator. C.G. was supported by the Robert S. Wennett Post-Doctoral Fellowship and the Shapiro-Silverberg Fund for the Advancement of Translational Research. C.G. and Z.W. were supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program, grant UL1 TR001866). P.D.B. and M.C.N. are Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigators. This article is subject to HHMI’s Open Access to Publications policy. HHMI lab heads have previously granted a nonexclusive CC BY 4.0 license to the public and a sublicensable license to HHMI in their research articles. Pursuant to those licenses, the author-accepted manuscript of this article can be made freely available under a CC BY 4.0 license immediately upon publication.

Author contributions