Abstract

After the COVID-19 pandemic, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) came to a halt, however, we chose to reinvent our study and shifted to a home-based, telehealth format for intervention delivery to support children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and their families. Children with ASD have social communication impairments and perceptuo-motor and cognitive comorbidities. Continued access to care is crucial for their long-term development. We created a general movement intervention to target strength, endurance, executive functioning, and social skills through goal-directed games and activities delivered using a telehealth intervention model. Our family-centered approach allowed for collaboration between trainers and caregivers and made it easy for families to replicate training activities at home. While more studies comparing telehealth and face-to-face interventions are needed, we encourage researchers and clinicians to consider family-centered telehealth to increase the likelihood of carryover of skills into the daily lives of children and ultimately enhance their long-term development.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted healthcare delivery around the world as a result of mandatory lockdowns and virus transmission safety protocols (i.e., social distancing and limited in-person services). At the onset of the pandemic, 74% of children with disabilities in the US lost access to at least 1 therapy or educational service.1 Children with developmental disabilities, such as those with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and their families experienced high levels of stress due to the loss of services. The sudden disruption to routines, transitions in and out of online learning, and lack of one-on-one support have presented significant challenges for children with ASD who lack the cognitive flexibility to easily adapt to changes, thereby exacerbating their negative behaviors2. Parents provided new structure to the daily schedules of their children, managed their problem behaviors, and ensured their continued developmental progress.2,3 Many also experienced the extra burden of managing their child’s needs with their own workload from home.

Clinical researchers and clinicians made similar adaptations to continue offering therapeutic services to children and families. Within a few months, healthcare providers moved to telehealth using privacy-compliant videoconferencing technologies (Zoom, Webex, etc.). They developed instructional materials for parent education in the form of handouts, visuals, and instructional videos. They also offered shorter and more flexible scheduling options to accommodate parent schedules. During telehealth delivery, parents played a more active role in guiding and assisting their childen. Through our experiences conducting intervention research during the pandemic, we learned that there is more than one way of providing care in addition to face-to-face interactions. In this brief report, we describe our experiences of modifying a face-to-face movement intervention for children with ASD into a telehealth format.

Children with ASD have social communication impairments such as poor social reciprocity and impaired verbal and non-verbal communication skills.4,5 They have perceptuo-motor comorbidities including poor motor coordination, balance, strength and endurance, and motor planning and praxis.4–9 They also have impaired executive functioning associated with motor impairments such as response inhibition, cognitive flexibility, and working memory.5,8–10 Our past face-to-face interventions using music, robot interactions, and yoga have shown positive effects in children with ASD including improved verbalization, imitation, and gross motor skills compared to a comparison group receiving standard-of-care seated play.11–15

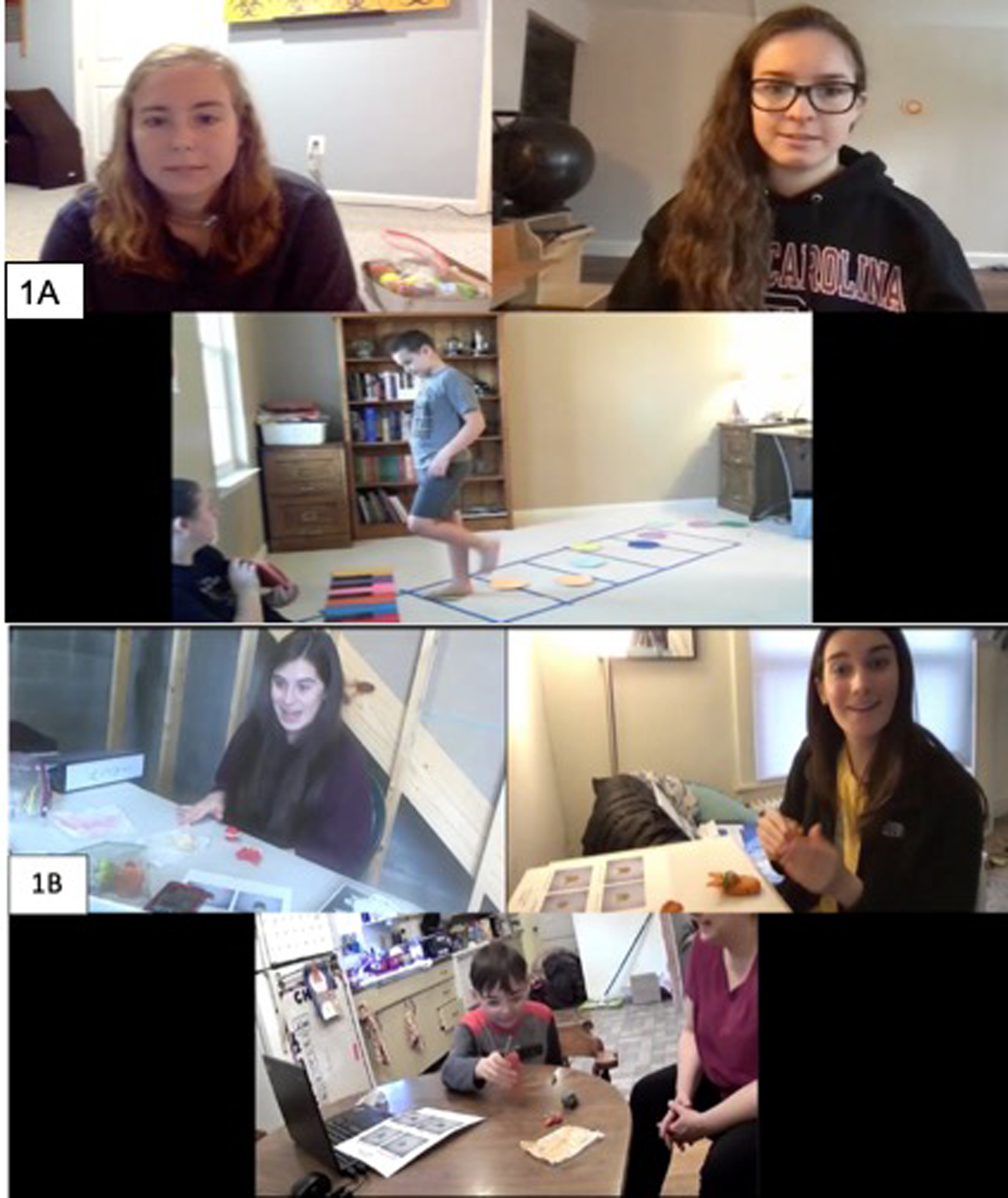

In our ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT) we compared the effects of a general movement intervention devoid of creative/musical activities to a standard-of-care, seated play intervention (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 2). The standard of care for children with ASD involves facilitating academic and communication skills during contexts such as book reading or naturalistic seated play during special education and speech therapy as well as fine-motor skills (e.g., hand dexterity games, building, arts and crafts, writing practice, etc.) during occupational therapy (Table 2). The general movement intervention developed in this study targets gross-motor abilities (i.e., strength, endurance, agility and coordination), cognitive skills (i.e., executive functioning), and social communication skills (i.e., turn taking, spontaneous and responsive communication, and relationship building) through a variety of goal-oriented games and exercises (Table 1). For instance, strength is targeted through whole-body exercises such as pushups, lunges, etc., endurance is built through timed locomotor games involving jumping, hopping, running, etc., while agility and coordination are practiced during object control games and obstacle courses. The games are played between children and trainers using a turn taking model to encourage continuous social monitoring and back and forth communication and imitation. Executive functioning skills are challenged by incorporating task shifting, object sorting, directional changes, multistep movement sequences, and movement inhibition within a variety of goal-oriented games. One exemple game is the “triathlon” that uses 3 different props, each associated with a unique gross motor skill that changes after each round of play. During the different practice rounds, the trainer, parent, and child take turns hopping across a line of yoga spots, lateral jumping over plastic cups, and leaping over beanbags on the floor. The use of different props associated with different motor skills promotes executive functioning skills such as response inhibition, task shifting, and working memory. The children are motivated by friendly competition with social partners which in turn improves the child’s confidence in their own ability to participate in socially-embedded motor games. Testing measures include subtests of the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOT) and the Test of Gross Motor Development (TGMD) for motor skills, computerized Flanker and Reverse Flanker tests of executive functioning for cognitive skills, and video coding of verbalization and affective states during training sessions for social communication skills. Although originally planned as a face-to-face intervention study, with the onset of the pandemic, we were forced to rethink our study’s method to enable continued research through the lockdown and limited social contact periods.

Figure 1:

A telehealth-based, general movement (1A) or standard of care, seated play (1B) intervention.

Table 1:

Conditions and Skills Promoted In Each Session

| General Movement Group - Exemplar Session | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Training Activities | Props & Materials | Targeted Skills | |

| 1 | Hello Game | Introductions and social bids:

|

Movement dice with each face suggesting different actions and related questions to elicit conversations |

|

| 2 | Warmup | Dynamic Stretches:

|

None |

|

| 3 | Grow Strong | Strength Exercises:

|

Water bottles as weights, yoga mat, pool noodle |

|

| 4 | Speed Up | Endurance & Ball Games:

|

Balls, beanbags, boxes, yoga spots |

|

| 5 | Cool down | Static Stretches:

|

none |

|

| 6 | Breathing | Deep Breathing Practice:

|

none |

|

| 7 | Goodbye | Cleanup & Farewell:

|

none |

|

Table 2:

Conditions and Skills Promoted in Each Standard of Care, Seated Play Session

| Standard of Care, Seated Play Group - Exemplar Session (Space theme) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Training Activities | Props & Materials | Targeted Skills | |

| 1 | Hello Game | Introductions and social bids:

|

Alphabet movement chart |

|

| 2 | Reading | Child-appropriate books:

|

Book chosen based on child’s reading level (based on parent input) |

|

| 3 | Hand & Finger Warmup | Quick/Coordinated Hands Movements:

|

String, beads; Peg, pegboard |

|

| 4 | Building | Playdoh, Lego, or Zoob:

|

Playdoh |

|

| 5 | Free Build | Playdoh, Lego, or Zoob:

|

Playdoh moon and stars |

|

| 6 | Arts & Crafts | Coloring, Cutting, Pasting:

|

Planet coloring sheet, crayons, glue-stick, glitter glue, construction paper, scissors |

|

| 7 | Goodbye | Story Book & Farewell:

|

Storybook binder, construction paper, pen/marker, glue |

|

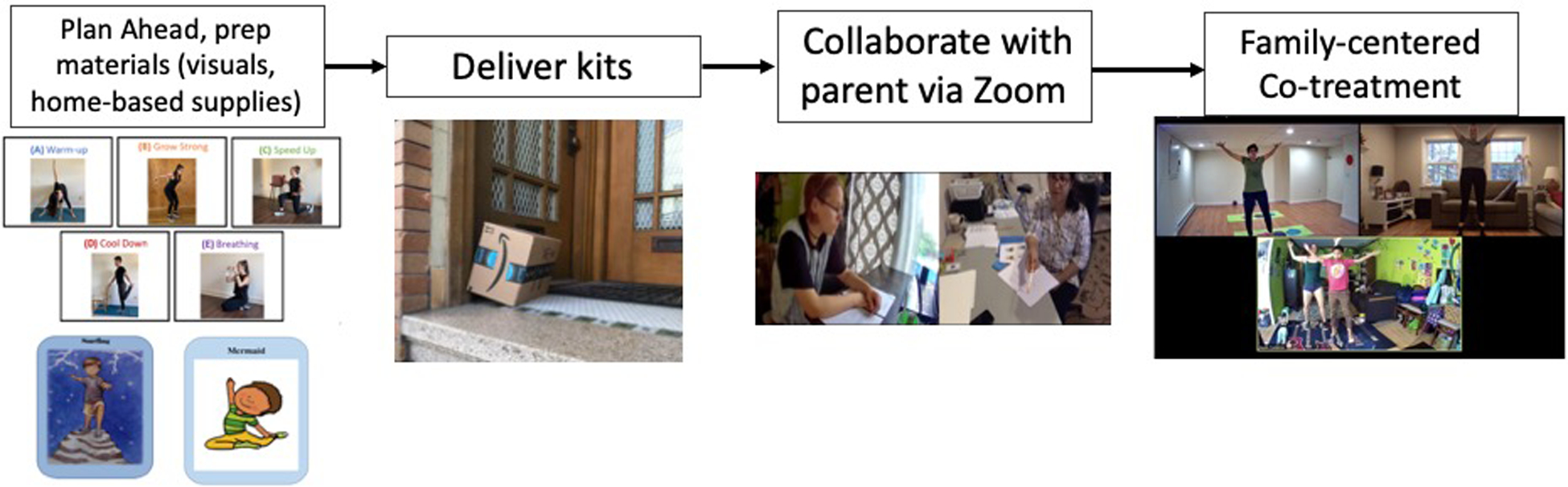

Reinventing our research approach during COVID-19

While many RCTs came to a halt, we chose to reinvent our study by shifting to a home-based, telehealth format using Zoom videoconferencing (Figure 1).16–18. Given that families were concerned about lack of optimal learning experiences for their children1, it was crucial for our research team to create materials and strategies that would best support children in our study. Similarly, some families had financial difficulties during the pandemic.19 By providing intervention materials to families, we reduced the participation-related burden associated with travel and obtaining intervention supplies.2,16–18 Additional steps to make the intervention feasible, meaningful, and easy-to-implement for families included designing of exercise picture cards, development of activities utilizing household objects (i.e., baking sheets and water bottles), creation of instructional videos and visuals for the games, caregiver input to tailor activities appropriately, and additional meetings with caregivers to promote a researcher-caregiver team-based approach (Figure 2). A change in our re-invented intervention is the addition of family involvement that provides an opportunity for multiple family members (caregivers and siblings) to remain physically active and socially connected during the pandemic. Family members take on various roles as the child’s peer, facilitator, and teacher or co-therapist while also developing rapport with the remote expert trainer. The trainers demonstrate the activity on the screen. The parent and/or child view the demonstrated activity (note that some children required additional trainer and caregiver prompting to initiate and sustain attention towards the screen). In some cases, the parent participates by taking a turn and modeling the activities to provide an additional demonstration to the child. Parents are encouraged to provide additional visual, verbal, or gestural prompts/feedback as needed by the child as well as affirmations/reinforcement. The parent and trainers work together to facilitate both spontaneous and responsive, verbal and nonverbal communication. For example, the hello and goodbye conditions typically involve interactive games where the child is encouraged to talk about their daily routines, favorite things or every day challenges. Throughout the other session activities, the child is asked to choose exercises based on visuals shown (Figure 2), asked to come up with own exercises/games and show them to the trainer, setup and cleanup the supplies (spots, beanbag, etc.) for games based on visuals or trainer demonstration. Each session includes helping bids, regular check-ins with virtual participants to ensure breaks as needed, and time for reflections about /session activities. All of these strategies help elicit a natural back and forth communication between the child and the parents and help build relationships between the child and adults involved across training sessions. We find that this family-centered, collaborative effort has been invaluable in creating positive experiences for the children in our study.

Figure 2:

Telehealth-based, family centered-interventions by developing and delivering kits to families in their homes and meeting remotely to deliver the training activities.

The value of the telehealth approach to intervention research

As clinical research and practice models change, it is important to identify critical challenges, collaborate with families and healthcare professionals, be open to new ideas, and continue to innovate and learn from past experiences. Previously, telehealth interventions were considered an option for families in rural areas who had difficulty traveling to the clinical site; however, telehealth interventions may also provide opportunities to better engage families across rural and urban settings by following a family-centered approach when caring for children with ASD. The telehealth approach allows researchers to expand participation over a larger geographic area, reduce commuting costs, and offer more flexible schedules to families. Children with ASD learn in their natural environment, while expanding their social network. Similarly, parents and children interact as they learn together and explore creative ways to spend time together engaged in therapeutic games/activities. Our family-centered, collaborative approach using household supplies is much more pragmatic and replicable for families to continue independently beyond the research study, thereby increasing the likelihood of long-term carryover of skills into daily life.

Limitations and Future Recommendations

The transition to a telehealth format has not come without its limitations including establishing comfort navigating videoconferencing platforms, issues with unstable internet connections, audio and visual synchronicity delays, and audio override that only allows one person to speak clearly at a time. We provide parents with easy-to-follow instructional videos and documents to assist in troubleshooting, if necessary. Outside the realm of technology, caregivers are struggling with the increased workload brought on by the pandemic,3,16–18 and an additional responsibility of participating in training sessions may not be feasible in all households. Researchers should work with caregivers directly to set reasonable expectations given family constraints. Similarly, maintaining child engagement during online interactions is challenging and children with significant communication and behavioral challenges may not frequently attend to the computer screen. We recommend teaching the caregiver first such that the child can follow an in-person model when doing the activities.

We continue to learn and constantly make changes to best support our participants with varied abilities. Although findings from previous research are promising,20–21 the effects of telehealth interventions in comparison to face-to-face interventions remain to be studied. We plan to recruit equal number of children across face-to-face and telehealth intervention delivery methods in both our experimental and comparison groups to systematically examine the effects of telehealth versus face-to-face models of intervention delivery. Finally, we encourage researchers to consider the value of family involvement and individualized interventions to support skill carryover into daily life and promote children’s long-term, multisystem development through the use of telehealth-based interventions.

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to the SPARK children and families who participated in this study. We also thank the SPARK clinical sites and SPARK research participant match service staff for their help with participant recruitment. Researchers may contact SPARK study research participant match service here: https://wp-qa.sparkforautism.org/spark-research-match/. We would like to thank all the children and families who have participated in this intervention study, and the undergraduate students, Marissa Heino, Sarah Williams, Emily Longenecker, Emma Fallon, Jill Dolan, and Hannah Laue from the University of Delaware and Catherine Myers from the University of Connecticut for their help with data collections and data analysis.

Grant support:

AB’s research was supported by a Clinical Neuroscience Award from the Dana Foundation and multiple National Institutes of Health grants (Grant #: 1S10OD021534–01, P20 GM103446, 1R01-MH125823-01). SS’s research was supported by a seed grant from the Institute of Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (inCHIP) and a Research Excellence Program grant from the University of Connecticut. The funders had no role in study design, data collection/analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement: The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jeste S, Hyde C, Distefano C, et al. Changes in access to educational and healthcare services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during COVID-19 restrictions [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 17]. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020;10.1111/jir.12776. 10.1111/jir.12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aishworiya R, Kang YQ. Including Children with Developmental Disabilities in the Equation During this COVID-19 Pandemic. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(6):2155–2158. 10.1007/s10803-020-04670-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ameis SH, Lai MC, Mulsant BH, Szatmari P. Coping, fostering resilience, and driving care innovation for autistic people and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):61. Published 2020 Jul 22. 10.1186/s13229-020-00365-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat AN, Landa RJ, Galloway JC. Current perspectives on motor functioning in infants, children, and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Phys Ther. 2011;91(7):1116–1129. 10.2522/ptj.20100294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhat AN. Motor Impairment Increases in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder as a Function of Social Communication, Cognitive and Functional Impairment, Repetitive Behavior Severity, and Comorbid Diagnoses: A SPARK Study Report. Autism Res. 2021;14(1):202–219. 10.1002/aur.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivasan S, Kaur M, Bhat A. (2018) Comparing motor performance, praxis, coordination, and interpersonal synchrony between children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Res. Devtl. Disab 72: 79–95. 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhat AN. Is Motor Impairment in Autism Spectrum Disorder Distinct From Developmental Coordination Disorder? A Report From the SPARK Study. Phys Ther. 2020;100(4):633–644. 10.1093/ptj/pzz190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shield A, Knape K, Henry M, Srinivasan S, & Bhat A. Impaired praxis in gesture imitation by deaf children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism & Devtl. Lang. Impairments 2017; Vol. 2(Jan issue). 10.1177/2396941517745674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhat A, Srinivasan S, Woxholdt C., Shield A. Differences in praxis performance and receptive language during fingerspelling between deaf children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016; 22(3):271–282. 10.1177/136236131667217.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman LM, Locke J, Rotheram-Fuller E, Mandell D. Brief Report: Examining Executive and Social Functioning in Elementary-Aged Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(6):1890–1895. 10.1007/s10803-017-3079-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srinivasan SM, Bhat AN. A review of “music and movement” therapies for children with autism: embodied interventions for multisystem development. Front. Integr. Neurosci 2013;7:22. Published 2013 Apr 9. 10.3389/fnint.2013.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivasan SM, Kaur M, Park IK, Gifford TD, Marsh KL, Bhat AN. The Effects of Rhythm and Robotic Interventions on the Imitation/Praxis, Interpersonal Synchrony, and Motor Performance of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Autism Res Treat. 2015;2015:736516. 10.1155/2015/736516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaur M, Bhat A. Creative Yoga Intervention Improves Motor and Imitation Skills of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Phys. Ther 2019;99(11):1520–1534. 10.1093/ptj/pzz115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan S, Lynch K, Gifford T, Bubela D, Bhat A. The effects of robot-child interactions on imitation and praxis skills of children with and without autism between 4 to 7 years of age. Percep. and Mot. Skills, 2013; 116 (3), 889–906. 10.2466/15.10.PMS.116.3.885-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur M, Gifford T, Marsh K, Bhat A. Effect of Robot–Child Interactions on Bilateral Coordination Skills of Typically Developing Children and a Child With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Preliminary Study. J Mot Learn Dev. 2013;1(2):31–37. 10.1123/jmld.1.2.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhat A, Su W, Cleffi C, Srinivasan S. A Hybrid Clinical Trial Delivery Model in the COVID-19 era. Phys. Ther 2021; 101:1–5. 10.1093/ptj/pzab116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srinivasan S, Su W, Cleffi C, Bhat A. (2021) From Social distancing to Social connections: Insights from the Delivery of a Clinician-Caregiver co-mediated Telehealth-based Intervention in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front in Psychiatr. 2021, 12:700247. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.700247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su W, Srinivasan S, Cleffi C, Bhat A. Short Report on Research Trends in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Use of Telehealth Interventions and Remote Brain Research in Children with ASD. Autism. 2021; (6):1816–1822. 10.1177/13623613211004795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholas DB, Belletrutti M, Dimitropoulos G, et al. Perceived Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Pediatric Care in Canada: A Roundtable Discussion. Glob Pediatr Health. 2020;7:2333794X20957652. Published 2020 Sep 30. 10.1177/2333794X20957652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallisch A, Little L, Pope E, Dunn W. Parent Perspectives of an Occupational Therapy Telehealth Intervention. Int J Telerehabil. 2019;11(1):15–22. Published 2019 Jun 12. 10.5195/ijt.2019.6274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wainer AL, Ingersoll BR. Increasing Access to an ASD Imitation Intervention Via a Telehealth Parent Training Program. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(12):3877–3890. 10.1007/s10803-014-2186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]