Abstract

A collagen-rich tumor microenvironment (TME) is associated with worse outcomes in cancer patients and contributes to drug resistance in many cancer types. In melanoma, stiff and fibrillar collagen-abundant tissue is observed after failure of therapeutic treatments with BRAF inhibitors. Increased collagen in the TME can affect properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM), including stiffness, adhesiveness, and interaction of integrins with triple helix forming nanostructures. Decoupling these biochemical and biophysical properties of the ECM can lead to a better understanding of how each of these individual properties affect melanoma cancer behavior and drug efficacy. In addition, as drug treatment can induce cancer cell phenotypic switch, cancer cell responsiveness to the TME can be dynamically changed during therapeutic treatments. To investigate cancer cell phenotype changes and the role of the cancer TME, we utilize poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels functionalized with collagen mimetic peptides (CMPs), or prepared an interpenetrating network (IPN) of type І collagen within the PEG system to culture various melanoma cell lines in the presence or absence of Vemurafenib (PLX4032) drug treatment. Additionally, we explore the potential of using CMP functionalized PEG hydrogels, which can provide better tunability, to replace the existing invadopodia assay platform based on fluorescent gelatin.

Keywords: hydrogels, collagen mimetic peptides, interpenetrating polymer networks, melanoma cells, tumor microenvironments, invadopodia, MMP activity

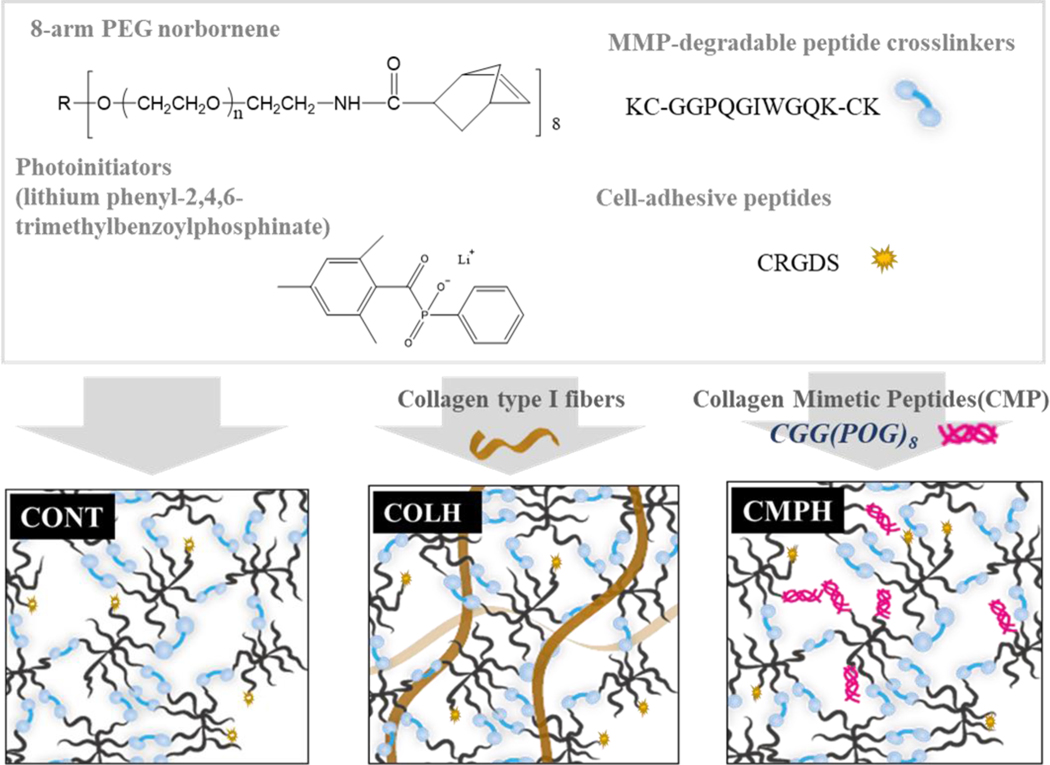

Graphical Abstract

During targeted therapy to treat melanoma cancer with BRAF inhibitors, melanoma cells synthesize more fibrillar collagens. In this work, the effect of the collagen nanostructure on the invasiveness of melanoma cells is investigated. For this, 2D and 3D hydrogels designed to decouple biochemical and biophysical cues of collagen structure are synthesized to culture melanoma cells under BRAF inhibitors treatments.

1. Introduction

During cancer progression, cancer cells encounter a dynamic tumor microenvironment (TME), which include changes in the biochemical and biophysical features of the extracellular matrix (ECM), recruitment of neighboring cell types, and local oxygen concentrations and formation of nutrient gradients.[1–4] Recently, the TME has attracted more attention because it can affect cancer progression as well as cell invasion, apoptosis, proliferation, and even influence treatment strategies used to target cancer cells.[5–9] For example, a highly fibrous collagen rich TME is often related to poor outcomes in cancer patients.[8–12] A few studies have reported that increased fibrillar collagen has been observed in patients with relapsed melanoma after failure of BRAF inhibitor treatment.[13,14] An in vitro study also showed that the COL1A1 gene was upregulated after BRAF or MEK inhibition regardless of BRAFV600E mutation in melanoma.[13] However, it is not clear whether the increased fibrillar collagen contributes to poor outcomes in melanoma patients.

There is still debate over how the collagen fibrils will affect melanoma cell behavior and the efficacy of drug treatments. While collagen can be a physical barrier that prevents cancer cell migration, this ECM component can also reduce drug penetration, increase tumor-initiating potential, alter cell adhesion, and promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in many cancer cell types.[15] Thus, the role of collagen in tumor malignancy is pleiotropic—it possesses both anti-tumor and pro-tumor properties.[16] Additionally, due to the inherent heterogeneous properties of natural collagen fibers, it is hard to decouple and understand how each feature of collagen (i.e., stiffness, fiber structure, adhesiveness, and biochemical properties) may affect cancer cell behavior.

To decouple the role of the biochemical from the biophysical properties of collagen, collagen mimetic peptides (CMPs) have been used in vitro to tailor the adhesivity, fiber diameters and lengths, and functionality.[17] CMPs have been developed and studied by multiple groups and are typically composed of repeating trimers of glycine, proline and hydroxyproline ((GPO)n or (GPP)n). The short amino acid sequence in CMPs mimics the basic structure of collagen that is responsible for the formation of the triple helix. CMPs are typically around 10 nm in length, depending on the number of repeating units in the peptide, which is usually 5–10.[17] By adding a cell adhesive sequence or photo-responsive moiety, the peptide’s properties can be further modified.[18–22] These highly controllable collagen-mimics allow researchers to ask targeted questions about the role of collagen’s structure on cell-matrix interactions, matrix remodeling, and its effects on cell migration.

Here, we sought to systematically study the role of the melanoma TME on the formation of invadopodia and MMP activity of melanoma cells. PEG hydrogels were used as the base formulation (Cont(d), Figure 1), which was subsequently modified with either CMPs or full-length collagen molecules. Specifically, we functionalized PEG hydrogels with the CMP (CGG(POG)8), (CMPH, Figure 1) or embedded whole collagen fibers as an interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) (Col-IPN, Figure 1) and then used quantitative image analysis and biochemical assays to investigate the role of the collagen triple helix structure on melanoma cell morphology, MMP activity, and invasion. The CMPH formulations allowed us to investigate the specific role of the collagen triple-helix structure on melanoma cells. Unlike type I collagen, which can be heterogenous with fibers of varying lengths and diameters and a range of biologically active component, the CMPH formulations are more homogeneous in their properties. Additionally, a PEG-based hydrogel with an increased modulus (Cont(s)) without any collagen structure was used to decouple the effects of matrix stiffness from the effect of the triple helix structure on melanoma cell-matrix interactions. Both the morphology of melanoma cells cultured in 3D hydrogels or on top of the hydrogels (2D), protease activity, and proliferation were monitored, analyzed, and compared using Cont(d), CMPH, Col-IPN, and Cont(s) hydrogel formulations. Upon quantifying the effects of the TME on cell behavior, we then investigated how the fibrillar collagen architecture might influence the melanoma cells’ response to BRAF inhibition with Vemurafenib (PLX4032). The results in this study show that inhibiting the interactions between melanoma cells and collagen nanostructure could become more important target to prevent drug resistance after therapeutic treatment with BRAF inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the hydrogel formulations used in this study. Hydrogel’s precursors were an 8-arm 40 kDa PEG-norbornene, the cell-adhesive peptide CRGDS, and an MMP-degradable peptide crosslinker KC-GGPQGIWGQK-CK. When the hydrogel precursors were exposed to UV light (365 nm, 4 mW/cm2), polymerization was initiated by the cleavage of the photoinitiator, lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), and the resultant generation of free radicals. The polymer network was formed via thiol-ene reactions between PEG-norbornene and thiol groups located in cysteine residues. To prepare the collagen and PEG interpenetrating network, commercial rat tail type I collagen was added and neutralized to form fibers before photopolymerization. To prepare the collagen mimetic peptide (CMP) hydrogels, CMPs with terminal cysteine were added.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of CMPs and collagen-modified PEG hydrogels

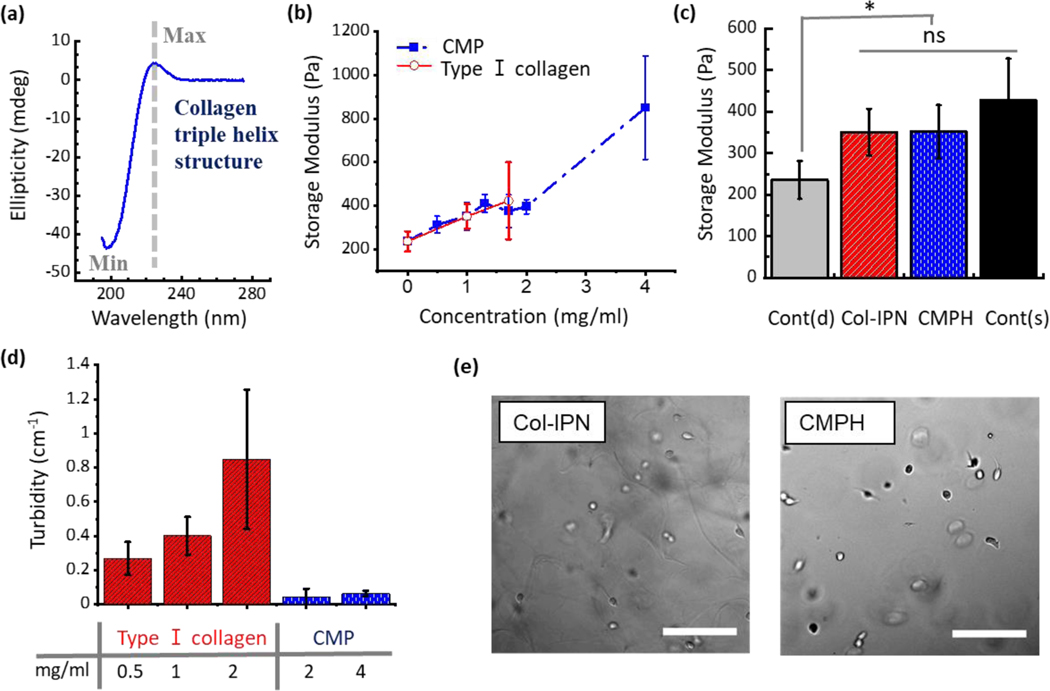

Collagen mimetic peptides (CMPs) with a sequence of CGG(POG)8, were synthesized using a peptide synthesizer based on Fmoc-based solid phase chemistry. To confirm the formation of a collagen-like triple helix, circular dichroism (CD) studies were performed. The maximum peak at ~225 nm and the minimum at ~200 nm (Figure 2a) shows the presence of the characteristic triple helix structure, as reported in the literature; these also correspond to the features found in the CD spectrum of natural collagen.[18,23]

Figure 2.

(a) Circular dichroism spectrum of CMP. Ellipticity as a function of wavelength. (b) Storage modulus of hydrogels increases with increasing concentration of CMPs and type I collagen. (c) Storage modulus of the four hydrogels used in this study. Cont(d) (PEG hydrogel without any addition of CMPs or collagen, G’ = 235.7 ± 45.6 Pa), Col-IPN (Interpenetrating polymer network of PEG hydrogels and 1 mg/ml type I collagen, G’ = 350.7 ± 56.3 Pa), CMPH (PEG hydrogels functionalized with 2 mg/ml CMPs, G’ = 395 ± 32.8 Pa), and Cont(s) (PEG hydrogel without any addition of CMPs or collagen, G’ = 427 ± 100 Pa). One-way ANOVA with Turkey’s Multiple Comparison Test was performed to compare the results between groups and single asterisk [*] denotes p < 0.05. (d) Turbidity of neutralized type I collagen and CMPs in PBS solutions. (e) Bright-field microscopy images of melanoma cells (WM35) encapsulated in Col-IPN and CMPH hydrogels. Scale bar: 200 μm.

CMP–functionalized hydrogels (CMPHs) were synthesized using thiol-ene photo-click chemistry. An 8-arm 40kDa PEG-norbornene and MMP degradable crosslinker, cell adhesive moiety CRGDS, and CMPs were all reacted under ultraviolet (UV) light using a radical mediated thiol-ene polymerization (Figure 1). Ellman’s assay was performed to characterize the concentration of free thiols before and after the polymerization reaction (Figure S1a). No thiol was detected after UV exposure to the pre-polymer solution, and this result show that all thiol-containing peptides (MMP degradable crosslinker and collagen mimetic peptides) were reacted and bound into the polymer backbone. An increase in storage modulus was observed with a higher concentration of CMPs functionalized into PEG hydrogels (CMPH). A similar trend was observed in collagen interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) PEG hydrogels (Col-IPN).

In this work, we used the Col-IPN (1 mg/ml type I collagen, G’ = 350.7 ± 56.3 Pa) and CMPH (2 mg/ml CMP, G’ = 395 ± 32.8 Pa) formulations for the melanoma cell studies. Because we could observe more morphology changes in WM35 cells when cultured in the hydrogels functionalized with a higher concentration of CMPs, we chose to use 2 mg/ml CMPs instead of 1 mg/ml CMPs. Two control groups were included that comprised the PEG hydrogel without any addition of CMPs or collagen. In the control group labelled Cont(d) (G = 235.7 ± 45.6 Pa), the MMP concentration was kept at the same level as the experimental groups. The second control group, labelled Cont(s) (G’ = 427 ± 100.5 Pa) was used to account for the increased stiffness observed with the increased concentration of CMPs and type I collagen (Figure 2b). The modulus of the Col-IPN, CMPH, and Cont(s) hydrogels were not statistically different from each other, although all three groups were increased from the Cont(d) group (Figure 2c). The loss tangent was also measured since CMPH and Col-IPN mimic or contain collagen, which is a known viscoelastic biomaterial. Tan delta (tan δ = G”/G’) tended to be higher in Col-IPN and CMPH hydrogels (Figure S1b, Supporting Information). However, no significant difference in the tan δ data was detected between the tested hydrogels.

The turbidity of collagen strand dispersion and CMP was measured in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to gauge the effect on optical characterization methods, such as fluorescence (Figure 2d and 2e). This is potentially due to collagen forming structures, which are more heterogeneous than CMP, and which may grow to reach a scale comparable to visible light wavelength (Figure 2e, Col-IPN). Therefore, CMP hydrogels may have advantages with colorimetric and fluorometric assay because of their lower turbidity while still providing a homogeneous, collagen-like microenvironment for cell studies. Furthermore, one can retain control over the microenvironment from the tunability on fiber length, thickness, and adhesiveness by chemistry.

2.2. The formation of invadopodia in melanoma cell spheroids depends on the hydrogel microenvironment and BRAF inhibition

Next, we sought to determine cancer cell migration throughout the CMP and collagen type I hydrogel systems by encapsulating WM35 melanoma cells within the conditions and compared invadopodia formations relative to the controls. When the WM35 cell spheroids were cultured in the four different hydrogel miroenvironments, the fastest growth occurred in the Cont(d) hydrogels (6238 ± 2885 μm2), while the spheroids cultured in the other hydrogel systems (Cont(s), CMPH, and Col-IPN) were significantly smaller (2885 ± 1786 μm2, 4430 ± 2580 μm2, 3224 ± 1323 μm2 respectively, p < 0.001) (Figure S2, Supporting Information). The difference in growth rate might be explained by the fact that a higher level of compressive forces can build up in the stiffer hydrogel environment, which is known to inhibit cell proliferation. When cancer cells proliferate under confinement, it has been shown that nuclear p21 levels are elevated, and cell cycle progression and spheroid growth can be delayed.[24] At the interface between the matrix materials and the spheroids (pericellular region), no invasive cell phenotypes were observed. This finding suggested to us that the presence of fibrillar collagen or CMPs in the non-drug treated periods primarily resulted in reducing the spheroid size, as the surrounding TME is stiffer.

However, when the WM35 cell spheroids were treated with 100 nM of the BRAF inhibitor PLX4032, growth was inhibited, and a more invasive cell phenotype was observed (Figure 3). We speculate that with continuous BRAF inhibition, some of the WM35 cells undergo an epithelial to mesenchymal transition-like (EMT-like) phenotypic switch, as reported in other studies.[25,26] Both WM35 and WM115 cell spheroids cultured in the collagen-like microenvironments (CMPH or Col-IPN) became more invasive than either of the control hydrogels, Cont(d) and Cont(s) (Figure 3a). When the spheroids were stained for phalloidin and DAPI to visualize actin and the cell nuclei, respectively, most of the spheroids cultured in the CMPF (~88%) or Col-IPN (~95%) hydrogels formed invadopodia structures, which are highly degradative, actin-rich protrusions. In contrast, a smaller number of spheroids cultured in Cont(d) (~63%) and Cont(s) (~33%) had invadopodia (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Representative bright-field and fluorescence images of melanoma cell spheroids (WM35) embedded in hydrogels (3D culture): Cont(d), Cont(s), Col-IPN, and CMPH with continuous 100 nM PLX4032 drug exposure. More invasive phenotypes with actin-abundant protruding structures are observed from the WM35 spheroids cultured in Col-IPN and CMPH, implying the formation of more invadopodia in comparison to Cont(d) and Cont(s) conditions. Images in the top row (a) are bright-field micrographs (greyscale). Images presented in the bottom row of (a) are confocal fluorescence micrographs. Nuclei are stained in blue (DAPI) and F-actin filaments are stained in red (phalloidin). Scale bars in both the bright-field and confocal fluorescence micrographs are 100 μm. (b,c,d) Analysis of the percentage of WM35 spheroids with invadopodia (b) and the number of invadopodia per spheroid formed in Cont(d) (n=41), Cont(s) (n=40), CMPH (n=45), and Col-IPN (n=42) (c) Lengths of the invadopodia (d) formed in Cont(d) (n=278), Cont(s) (n=68), CMPH (n=281), and Col-IPN(n=283). One-way ANOVA with Turkey’s Multiple Comparison Test was performed to compare the results between groups. The box graph extends from the 25th to the 75th percentile. Single asterisk [*] denotes p < 0.05; double asterisks [**] denote p < 0.01; triple asterisks [***] denote p < 0.001 and quadruple asterisks [****] denote p < 0.0001.

The number of invadopodia per spheroid was significantly higher for the WM35 spheroids cultured in Col-IPN (6.72 ± 4.30) and CMPH (6.29 ± 4.04) compared to the spheroids cultured in Cont(d) (3.756± 3.76) or Cont(s) (2.17 ± 3.78) (Figure 3c). In addition, the length of invadopodia for the WM35 spheroids also varied significantly with the hydrogel composition. The length in CMPH was 10.7 ± 4.3 μm, and the length in Col-IPN was 9.9±2.8 μm, which were significantly longer than the lengths of the invadopodia grown in Cont(d) (3.5 ± 0.9 μm) or Cont(s) (7.8 ± 1.2 μm) (Figure 3d). Together, these results show that although PLX4032 treatment inhibited the growth of melanoma spheroids, BRAF inhibition with PLX4032 (100 nM) increases the invasiveness of WM35 cells. Additionally, the invasive protrusions were not observed when the hydrogels were synthesized without the CRGDS peptides. Thus, both the present of cell-adhesion motifs (CRGDS) and the collagen triple helix structure can affect the formation of invadopodia in WM35 cells, a radial growth phase human melanoma cell line.

2.3. 2D-cultured WM35 melanoma cells are more responsive to collagen or collagen mimetic structures under BRAF inhibition

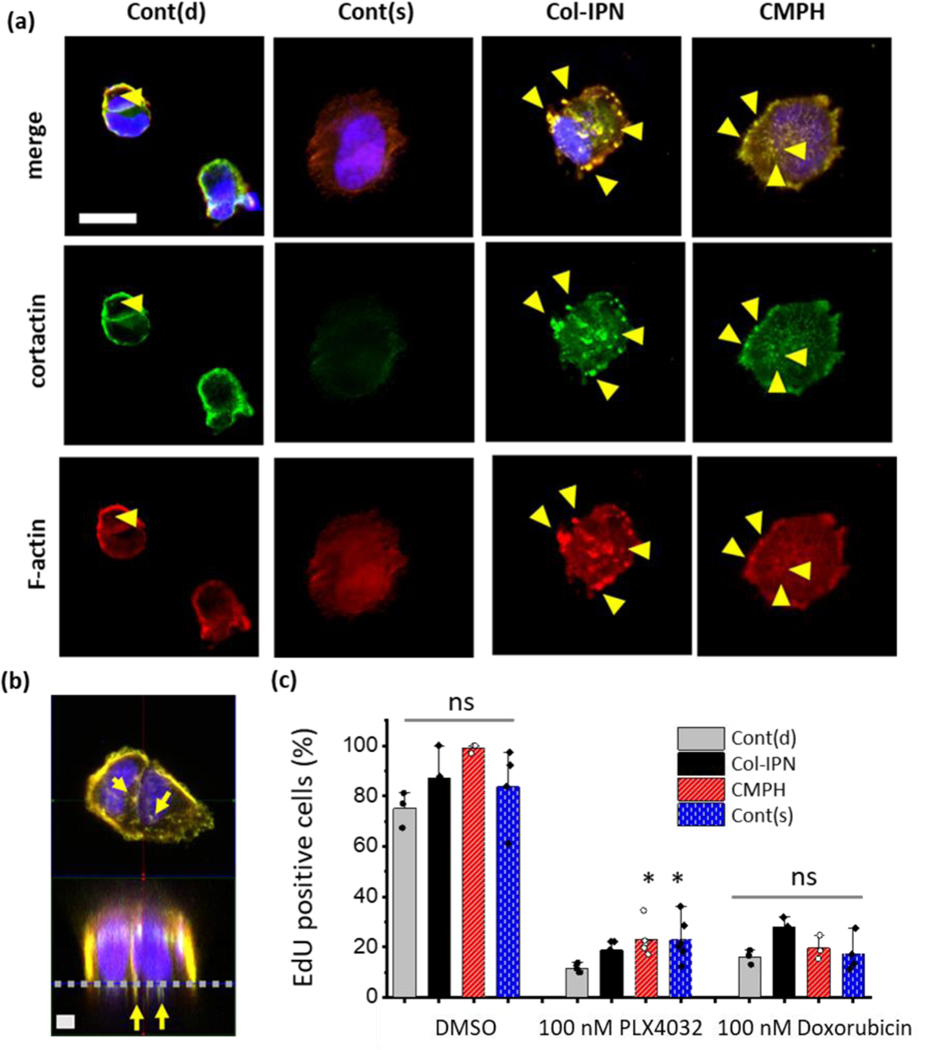

To further verify that the actin-rich migratory protrusions observed in three-dimensional (3D) cultures (Figure 3) are indeed invadopodia, WM35 cells were cultured as single cells on the surfaces of the same hydrogel formulations (2D) and immunostained for cortactin and actin to better visualize the invadopodia structures. Figure 4a is a representative image of the WM35 melanoma cells when seeded on the 2D hydrogel surfaces of Cont(d), Cont(s), Col-IPN, or CMPH for 5 hours under normal culture conditions and then for another 10 hours in the presence of 100 nM of PLX4032 treatment. Since invadopodia are defined as protrusions in which actin and cortactin are colocalized, the cells were immunostained with cortactin antibody, phalloidin, and DAPI, and the z-plane right beneath the nucleus was imaged and analyzed. Figure 4b shows the xz plane of a z-stacked image for the WM115 cells when cultured on Col-IPN. Here, invadopodia, which show positive stains for both cortactin (green) and actin (red), are observed right underneath the hydrogel’s surface.

Figure 4.

(a) Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of WM35 cells cultured on Cont(d), Cont(s), Col-IPN and CMPH 2D hydrogels. The cells are stained for F-actin (red), cortactin (green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue). WM 35 cells (1 ml of 20,000 cells/ml) were cultured on 2D hydrogels for 5 hours and then treated with 100-nM PLX4032 for an additional 10 hours. Scale bar: 20 μm. (b) Representative xy-plane and xz-plane images of WM115 cells cultured on Col-IPN 2D hydrogels. The grey dashed line indicates the surface of a hydrogel. Yellow arrows indicate invadopodia location. Scale bar: 5 μm. (c) The percentage of EdU-positive WM35 cells after culture on Cont(d), Cont(s), Col-IPN, and CMPH 2D hydrogels for 1 day and 12 hours with or without drug treatments. The data were acquired from at least three images of different samples. One-way ANOVA with Turkey’s Multiple Comparison Test was performed to compare the results between groups and single asterisk [*] denotes p < 0.05. A significantly higher number of CMPH or Col-IPN cultured cells are EdU positive when treated with 100 nM PLX4032.

When the WM35 cells were cultured on Cont(d), the cells remained rounded and did not spread. The cortactin and actin colocalized areas were only detected at the periphery of the cells. When the WM35 cells were cultured on the other control hydrogel with a stiffness (Cont(s)) more similar to the CMPH and Col-IPN, the cells tended to spread more, but only weak cortactin staining signals were observed. On the contrary, when the cells were seeded on CMPH or Col-IPN, an invadopodia or podosome-like structure was observed. The invadopodia structure was confirmed with cortactin and actin colocalized areas and shown to be yellow, as given in Figure 4a and 4b. However, the cells cultured on Col-IPN formed bigger, albeit fewer, invadopodia structures. than cells cultured on CMPH, where the invadopodia were smaller in size but higher in number. Our results from melanoma cells cultured in both 2D and 3D show that both CMP and type I collagen can induce the formation of invadopodia, but their length and diameter are affected differently by the peptide (CMP) versus full protein (type I collagen).

Beyond measurements of matrix invasiveness, the proliferation of melanoma cells was also studied using 2D hydrogel cultures (Figure 4c). S-phase cells in the population were fluorescently labelled according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Click‐iT EdU assay kit after culturing for a day. When the WM35 cells were cultured on each hydrogel without drug treatment, 75 ± 7% of the cells were EdU positive on Cont(d), 88 ± 13% of the cells were EdU positive on Cont(s), 100 ± 1% of the cells were EdU positive on Col-IPN, and 84 ± 16% of the cells were EdU positive on CMPH. With BRAF inhibition (100 nM PLX4032), proliferation was significantly reduced in all experimental conditions. There were 12 ± 2% EdU positive WM35 cells on Cont(d), 19 ± 4% on Cont(s), 23 ± 7% on Col-IPN, and 23 ± 9% on CMPH. However, this observation was dependent on cell type. Notably, when A375 cells, human metastatic melanoma cell line, were treated with 100 nM PLX4032, no significant differences in proliferation were observed across the hydrogel formulations (Figure S3. Supporting Information). While the percentage of proliferating cells cultured on Col-IPN and CMPH was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than the cells cultured on Cont(d) with the BRAF inhibition, treatment with a chemotherapy drug (100 nM doxorubicin treatment) led to no differences. Specifically, neither the Col-IPN nor CMP affected the proliferation of WM35 cells, as no significant changes in the EdU-positive cells were observed.

Together, we observed that the WM35 radial growth phase melanoma cell lines become more responsive to collagen or collagen mimetic structures under BRAF inhibition. WM35 cells with BRAF inhibition showed significantly more invadopodia structures and higher proliferation on 2D Col-IPN and CMPH. However, for the metastatic melanoma cell line (A375), no significant changes were observed in proliferation. The possible reasons for this are the EMT transition of melanoma cells upon BRAF inhibition, and the collagen-rich TME involved in the process.[25,26] Although this has not been covered in this study, exploring whether a collagen-rich microenvironment is involved in the EMT process during BRAF inhibition can make for an interesting future study.

2.4. Fluorescent assays of matrix degradation and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity shows accelerated matrix degradation of WM35 cells on CMPH

As a practical method to visualize cell-mediated matrix degradation of the ECM substrate, a commercially available fluorescent gelatin-based assay has been widely used.[27,28] However, the materials used in this assay is restricted to natural hydrogels, which usually have micrometer-scale pore size, and has not been applied to synthetic ECM hydrogel mimics.[29] In the latter, the mesh size of the materials are often nano-scale, which renders them unsuitable for short-term (~24 hours) matrix degradation assays.[30] For instance, Nelson et al. reported that the ECM rigidity contributes to invadopodia formation of CA1d breast carcinoma cells using soft or hard polyacrylamide gels; however, the authors needed to coat synthetic polyacrylamide hydrogels with gelatin and fluorescent fibronectin to visualize degradation.[31]

As a complementary approach that adds versatility, WM35 were cultured on the 2D hydrogel surfaces (Cont(d), CMPH, Col-IPN, Cont(s)) which are fluorescently labelled with Fluorescein-SSSS-C peptides during polymerization. After 4 hours of culture, the cell laden matrices were treated with or without 100 nM PLX4032 for an additional 4 hours. At that time, matrix degradation was observed beneath the cells along with a lower fluorescent intensity of the matrix materials compared to the regions that were more distal to the WM35 cells (Figure 5a). The brightest areas appeared around the cell periphery, likely due to charge interactions between the positively charged lysine residues of the MMP degradable crosslinker (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) and the negatively charged cell membranes. When the fluorescence intensity beneath the WM35 cells (F) was normalized to the fluorescence of the hydrogel in regions without cells (F0), we observed a decreased fluorescence in all hydrogel conditions, but a significantly lower fluorescence fold change (F/F0) was noted in the CMPH samples (Figure 5b, 5c). Regardless of the 100 nM PLX4032 treatment, WM35 degraded the hydrogel substrate significantly more on CMPH during this period (4 hours incubation and 4 hours drug treatment). This result confirms that substrate degradation is significantly faster when cells are cultured on collagen mimetic hydrogels (i.e., CMP functionalization of PEG hydrogels).

Figure 5.

(a) Representative images of WM35 cells cultured on 2D fluorescently labeled Cont(d), Col-IPN, and CMPH substrates. Scale bar: 20 μm. (b) Relative fluorescence (F/F0) of the FITC-conjugated hydrogels underneath the WM35 cells compared to bulk hydrogels cultured (for 8 hours) on Cont(d) (n=207), Cont(s) (n=196), Col-IPN (n=104), and CMPH (n=107) with continuous 100 nM PLX4032 drug exposure. (c) Relative fluorescence (F/F0) of the FITC-conjugated hydrogels underneath the WM35 cells compared to bulk hydrogels cultured (for 8 hours) on Cont(d) (n=79), Cont(s) (n=169), Col-IPN (n=141) and CMPH (n=181) without any drug exposure. (d) MMP activity of WM35 cells cultured on 2D Cont(d), Col-IPN, and CMPH substrates. Data are obtained from at least three biologically independent replicates. One-way ANOVA with Turkey’s Multiple Comparison Test was performed to compare the results between the groups. The box graphs in (b) and (c) extend from the 25th to the 75th percentile. Single asterisk [*] denotes p < 0.05; double asterisks [**] denote p < 0.01; triple asterisks [***] denote p < 0.001 and quadruple asterisks [****] denote p < 0.0001.

As malignant cancer cells must degrade the surrounding matrix and invade the ECM, upregulated protease activity is another marker that correlates with the invasiveness of cancer cells. Among the various proteases, MMP (including MMP-2, MMP-9, and MT1-MMP) has been a significant prognostic marker of cancer.[32–35] To measure MMP activity, we developed FRET-based sensor peptides in a previous study.[36,37] Using this method, the MMP activity of WM35 cells was monitored after being cultured on each type of hydrogel for 2 days (Figure 5d). The highest MMP activity (F/F0 = 1.75 ± 0.19) was measured in the cells cultured on Col-IPN with 1μM PLX4032 treatment, and the lowest MMP activity (F/F0 = 1.33 ± 0.03) was recorded for the cells cultured on Cont(d) without drug treatment (p < 0.05). As shown in Figure 5d, MMP activity of WM35 cells increases with drug treatment in the presence of collagen structure (CMPH and Col-IPN), although it is not statistically significant because of the high standard deviation between the samples and the low cell number used in this study. When using a highly concentrated (106 cells/ml) WM35 cell suspension instead of culturing cells on 2D hydrogels that only contained below 105 cells/ml, the immediate increase in MMP activity could be detected, and that was proportional to the amount of soluble CMPs added (F = 1878 ± 54 without CMP, F = 2532 ± 39 with 2 mg/ml of soluble CMPs) (Figure S4, Supporting Information). This result shows that CMPs can upregulate WM35’s overall MMP activity regardless of whether CMPs are bound to hydrogels.

3. Conclusions

In this work, we employed PEG-based hydrogels with type I collagen in IPN or functionalized with CMP to study how collagen’s triple helix structure affects the invasiveness of melanoma cancer cells (human melanoma cell line WM35). In a non-drug treated normal culture condition, collagen suppressed the spheroid growth by decreasing the degradability of the extracellular matrix and increasing the stiffness for the cell to migrate through. WM35 cells cultured in 3D hydrogels formed solid spheroidal cellular aggregates after 5 days of culture. However, many spheroids formed an actin-rich invadopodia structure under treatment with PLX4032 and showed EMT-like phenotypic switch. Especially in the presence of fibrillar collagen or CMP, WM35 cells formed a longer and more invadopodia structure. Higher proliferation and MMP secretion were also observed in the presence of the collagen structure. Together, the results show that the WM35 cells become more responsive to the fibrillar collagen TME after the BRAF inhibition. Based on tumor size, type I collagen showed more anti-tumor behavior in a normal culture condition, but it exhibited pro-tumor behavior after treatment with PLX4032.

CMP functionalized hydrogels can be a potential alternative to fibrillar collagen for the in vitro study of cancer cell invasion and invadopodia formation. CMPH could recapitulate TME niches, and the cancer cells behaved similarly to when they were cultured in Col-IPN. CMPH is optically clearer and easier to manipulate than collagen. Previous studies using synthetic hydrogels were limited in their ability to observe cancer cell invasion in a short time period due to the small mesh size of nanometer scale. This work improves on this point by reducing the time to observe such change by functionalizing PEG with CMP. This shows the potential of using CMP functionalized hydrogels to replace the existing invadopodia assays platform based on fluorescent gelatin.

4. Experimental Section

Synthesis and characterization of hydrogel precursors:

Eight-arm-PEG-norbornene (MW: 40,000 Da) was synthesized from eight-arm-PEG-amine (tripentaerythritol core) and 5-norbornene-2-carboxylic acid catalyzed by O-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU) N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), as previously reported.[36] The synthesized product was precipitated in diethyl ether and dialyzed against deionized water, after which coupling was confirmed with 1H NMR. The photoinitiator, lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), was synthesized as previously described.[38] Cell-adhesive CRGDS peptides and MMP-degradable peptide crosslinker, KCGPQG↓IWGQCK, were purchased from Bachem. The collagen mimetic peptides, CGG(POG)8, were synthesized using a Tribute Peptide Synthesizer (Gyros Protein Technologies) on Rink-amide MBHA resin with Fmoc-protected solid-phase peptide synthesis methods. After the synthesis, the peptides were dialyzed against the de-ionized water using a dialysis membrane with molecular weight cut-off of 8 kDa for 2 days and lyophilized. Peptides were confirmed using matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). A triple-helix formation of CMPs was confirmed using a circular dichroism (CD) spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics Chirascan Plus). A CD spectrum of 200 μM CMPs in PBS was taken between 180 and 280 nm with a 1 nm step size at room temperature.

Microscopic imaging and analysis:

Bright field images and non-confocal fluorescence images were acquired using an Operetta High-Content Screening System with a x 10 objective. Spheroid size was analyzed using Harmony software. To analyze the spheroids, the collected bright field images were inversed to change the dark spheroids to appear bright and further processed using the “analyze particle” function in the software. To analyze cellular migration, bright field images and Fiji software were utilized to manually track each cell. Confocal fluorescence images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 710 laser-scanning microscope using a 10× water immersion objective. Collected images were processed with Fiji software. The length and number of invadopodia were manually analyzed using Fiji software.

2D hydrogel synthesis and cell culture:

2D hydrogels were synthesized on 22 mm round glass coverslips. The surfaces of the coverslips were functionalized with a thiol group to improve the adhesion of the hydrogels. The coverslips were treated with oxygen plasma for 45 seconds, and the surface Si-OH group was made to react with vapor-deposited (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxysilane (MPTMS) to form an SiO2-MPTMS surface. Then 15 μl of a prepolymer solution was put on a sigmacote-treated glass slide and then covered with the prepared thiolated coverslips. The polymerization was carried out after 3 min of 4 mW/cm2 UV light exposure. The synthesized 2D hydrogels were washed with 5% IPA in a PBS solution and washed two more times with PBS. Each prepolymer solution was prepared as follows. To synthesize Cont(d), the control hydrogels, 1 mM 40K 8-arm ene, 1.3 mM MMP-degradable peptide crosslinkers, and 1 mM LAP in PBS were used. To prepare the Col-IPN 2D hydrogel, 1 mg/ml of rat-tail-type Ⅰ collagen was added and neutralized with 100 mM NaOH. The prepolymer solution of Col-IPN was incubated for 30 minutes in a 37°C CO2 incubator before it was photopolymerized. The prepolymer solution of CMPH had the same components as Cont(d) but with additional 2 mg/ml CMPs (0.8 mM). Cont(s) hydrogels were prepared from a 1 mM 40K 8-arm norbornene, 1.5 mM MMP-degradable peptide crosslinkers, and 1 mM LAP in PBS. After the photopolymerization, 1 ml of 20,000 cells/ml of WM35 was added in each well of a 24-well plate and incubated in a CO2 incubator for further experiments.

3D hydrogel synthesis and cell culture:

To incubate the cells in 3D hydrogels, a prepolymer solution was used with the same composition as that utilized in the 2D hydrogel preparation, and a concentrated WM35 melanoma cell suspension was added to produce a final cell concentration of 105 cells/ml. On top of the thiolated coverslips, a silicone o-ring gasket with a 6 mm inner diameter was attached, and 15 μl of each type of the prepared prepolymer solutions was added inside the ring-shaped silicone o-ring. After this was exposed to 4 mW/cm2 UV light for 3 minutes, a 3D hydrogel was formed. The 3D cultured cells were incubated in cell culture media [an RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin] for 1 day, and then further incubated with or without drug treatments (100 nM PLX4032) until day 5 or day 10. The culture medium that contained 100 nM PLX4032 or 0.1% DMSO was changed every other day.

Rheological characterizations of the hydrogels:

The shear storage modulus of the hydrogels was measured with a Discovery Hybrid Rheometer (TA Instruments) equipped with an 8mm parallel plate. Cylindrical hydrogels with an 8 mm diameter were prepared in a silicon mold and swollen in PBS overnight before the measurements were taken. The temperature was kept at 25°C. All storage moduli were measured in the ambient conditions of 25°C, and the real value could have been slightly different in the tissue culture condition of 37°C temperature and 95% relative humidity. The hydrogels were loaded onto a Peltier plate, and frequency sweep tests were performed from 0.1 rad/s to 10 rad/s. The storage and loss modulus value obtained at 1 rad/s was used in this study.

Turbidity measurement:

The turbidity of the PBS solution with type Ⅰ collagen and CMP added was measured based on the absorbance at 570 nm of the solution. To measure the absorbance of the type Ⅰ collagen, 0.5 mg/ml, 1 mg/ml, and 2 mg/ml collagen solutions in PBS were prepared using Rat-tail-type Ⅰ collagen (3.3 mg/ml), and the solutions were neutralized using a 100 mM NaOH solution. The neutralized pH was confirmed with pH paper, and the fiber formation of the collagen was awaited for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance values of the 2 mg/ml and 4 mg/ml CMP peptides were measured in the PBS solution. Then the turbidity (τ) of the solution was calculated using the following equation, where A is the absorbance and l is the path length in cm.[39]

| (1) |

Microscopic imaging and analysis:

Bright field images and non-confocal fluorescence images were acquired using an Operetta High-Content Screening System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with a x 10 objective. Spheroids size was analyzed using Harmony software (PerkinElmer). To analyze the spheroids, collected bright field images were inversed to change the dark spheroids to appear bright and further processed. To analyze cellular migration, bright field images and Fiji software were utilized to manually track each cell. Confocal fluorescence images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 710 laser-scanning microscope and collected images were processed with Fiji software.

Invadopodia analysis and immunofluorescence assay:

The number and length of the invadopodia of the 3D cultured WM35 cells were measured after 5 days or 10 days of culture with BRAF inhibition with 100 nM PLX4032 or with 0.1% DMSO. Bright field images of the 3D cultured spheroids were taken at z = 300 μm. From the brightfield images, the number and length of the invadopodia-like structure were analyzed using Fiji software. To acquire immunofluorescence images of the invadopodia of the cells cultured in 2D hydrogels or in 3D hydrogels, the WM35 cells that were 2D cultured after a day of PLX4032 treatment and the 3D encapsulated cells cultured in a normal culture medium for 1 day and then treated with 100nM PLX4032 for 4 days were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. The fixed samples were washed twice with PBS, permeabilized with PBST (0.1% TWEEN-20 in PBS) for 1 hour, incubated with 1% BSA in PBST for another 1 hour, and then incubated with a primary antibody of cortactin (sc-55579, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Finally, the F-actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin, and the nuclear DNA was stained with 4’−6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Proliferation assay of the 2D cultured cells:

For the proliferation assay, the cells were cultured on the 2D hydrogels for a day and then further cultured with EdU for 12 hours. The proliferating cells were determined with the Click-iT™ EdU Proliferation Assay following the manufacturer’s protocol. For the MMP activity assay, a day after the cell seeding, PLX4032 or DMSO was added to the cells.

MMP activity assay and substrate degradation assay:

For the MMP activity analysis, a FRET-based peptide synthesizer was used. The FRET based peptide sensor was synthesized as previously reported.[36] Briefly, an MMP-cleavable sequence with Dabcyl and Fluorescein dye at each end of the peptide was synthesized using the Fmoc protected peptide synthesis method with a Tribute peptide synthesizer (Gyros Protein Technologies). After the cleavage from an MBHA resin, the peptide was precipitated twice in diethyl ether and lyophilized and purified with HPLC. The peptide activity was confirmed as previously reported. After 1-day culture in normal culture conditions and further 1-day culture with PLX4032 (100 nM or 1 μM) or 0.1% DMSO treatment, the cells were incubated with the 100 μM MMP sensor peptide for 3 hours, and the fold fluorescence change at 488 nm was measured by dividing the fluorescence signal by the initial average fluorescence signal of the sensor peptide in the PBS (t0). For the 2D substrate degradation assay, the 2D hydrogels were synthesized with additional 500 μM Fluorescein-SSSS-C peptides. WM35cells were cultured on fluorescent hydrogels for 8 hours (4 hours in a normal culture solution plus 4 hours with 100 nM PLX4032 treatment or 0.1% DMSO treatment). The fluorescence at 480 nm was monitored using confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Statistical analysis:

Data are statistically analyzed using Origin 2020b Software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) or Graph Pad Prism (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). One-way ANOVA with Turkey’s Multiple Comparison Test was performed to compare the results between groups. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Single asterisk [*] denotes p < 0.05; double asterisks [**] denote p < 0.01; triple asterisks [***] denote p < 0.001 and quadruple asterisks [****] denote p < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Institutes of Health for support of this work through a research grant (NIH R01 DE016523 and NIH RO1 HL132353). MES acknowledges support from (NIH T32 HL007822).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Della S. Shin, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 80303

Dr. Megan E. Schroeder, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 80303

Prof. Kristi S. Anseth, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 80303 BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA 80303.

References

- [1].Quail DF, Joyce JA, Nat. Med 2013, 19, 1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sun Y, Cancer Lett. 2016, 380, 205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Trédan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF, JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst 2007, 99, 1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Emon B, Bauer J, Jain Y, Jung B, Saif T, Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J 2018, 16, 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chung M, Ahn J, Son K, Kim S, Jeon NL, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 1700196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wang L, Huo M, Chen Y, Shi J, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2018, 7, 1701156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu B, Liang S, Wang Z, Sun Q, He F, Gai S, Yang P, Cheng Z, Lin J, Adv. Mater 2021, n/a, 2101223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Najafi M, Goradel NH, Farhood B, Salehi E, Solhjoo S, Toolee H, Kharazinejad E, Mortezaee K, J. Cell. Physiol 2019, 234, 5700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dolor A, Szoka FC, Mol. Pharm 2018, 15, 2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Conklin MW, Eickhoff JC, Riching KM, Pehlke CA, Eliceiri KW, Provenzano PP, Friedl A, Keely PJ, Am. J. Pathol 2011, 178, 1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cox TR, Bird D, Baker A-M, Barker HE, Ho MW-Y, Lang G, Erler JT, Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1721 LP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].van Kempen LCLT, Rijntjes J, Mamor-Cornelissen I, Vincent-Naulleau S, Gerritsen M-JP, Ruiter DJ, van Dijk MCRF, Geffrotin C, van Muijen GNP, Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jenkins MH, Croteau W, Mullins DW, Brinckerhoff CE, Matrix Biol. 2015, 48, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hirata E, Girotti MR, Viros A, Hooper S, Spencer-Dene B, Matsuda M, Larkin J, Marais R, Sahai E, Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nallanthighal S, Heiserman JP, Cheon D-J, Front. Cell Dev. Biol 2019, 7, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fang M, Yuan J, Peng C, Li Y, Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].He L, Theato P, Eur. Polym. J 2013, 49, 2986. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu SQ, Tian Q, Hedrick JL, Po Hui JH, Rachel Ee PL, Yang YY, Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li Y, Foss CA, Summerfield DD, Doyle JJ, Torok CM, Dietz HC, Pomper MG, Yu SM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2012, 109, 14767 LP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Santos JL, Li Y, Culver HR, Michael SY, Herrera-Alonso M, Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 15045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].San BH, Li Y, Tarbet EB, Yu SM, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 19907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stahl PJ, Romano NH, Wirtz D, Yu SM, Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee HJ, Lee J-S, Chansakul T, Yu C, Elisseeff JH, Yu SM, Biomaterials 2006, 27, 5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].V Taubenberger A, Girardo S, Träber N, Fischer-Friedrich E, Kräter M, Wagner K, Kurth T, Richter I, Haller B, Binner M, et al. , Adv. Biosyst 2019, 3, 1900128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ramsdale R, Jorissen RN, Li FZ, Al-Obaidi S, Ward T, Sheppard KE, Bukczynska PE, Young RJ, Boyle SE, Shackleton M, et al. , Sci. Signal 2015, 8, ra82 LP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Villanueva J, Vultur A, Lee JT, Somasundaram R, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, Cipolla AK, Wubbenhorst B, Xu X, Gimotty PA, Kee D, et al. , Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Díaz B, Bio-protocol 2013, 3, e997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bowden ET, Coopman PJ, in C SCBT-M. Mueller B, in Cytometry, Academic Press, 2001, pp. 613–627. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arevalo RC, Urbach JS, Blair DL, Biophys. J 2010, 99, L65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang Y, Zhang S, Benoit DSW, J. Control. Release 2018, 287, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Alexander NR, Branch KM, Parekh A, Clark ES, Iwueke IC, Guelcher SA, Weaver AM, Curr. Biol 2008, 18, 1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Talvensaari-Mattila A, Pääkkö P, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Br. J. Cancer 2003, 89, 1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nikkola J, Vihinen P, Vuoristo M-S, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P, Kähäri V-M, Pyrhönen S, Clin. Cancer Res 2005, 11, 5158 LP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Overall CM, Kleifeld O, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vasala K, Pääkkö P, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Urology 2003, 62, 952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shin DS, Tokuda EY, Leight JL, Miksch CE, Brown TE, Anseth KS, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2018, 4, 378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Leight JL, Tokuda EY, Jones CE, Lin AJ, Anseth KS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2015, 112, 5366 LP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Bowman CN, Anseth KS, Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhu J, Kaufman LJ, Biophys. J 2014, 106, 1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.