Abstract

Background:

Bereaved family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans are less likely than families of White Veterans to provide favorable overall ratings of end-of-life (EOL) care quality; however, the underlying mechanisms for these differences have not been explored. The objective of this study was to examine whether a set of EOL care process measures mediated the association between Veteran race/ethnicity and bereaved families’ overall rating of the quality of EOL care in VA medical centers (VAMCs).

Methods:

A retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of linked Bereaved Family Survey (BFS), administrative and clinical data was conducted. The sample included 17,911 Veterans (mean age: 73.7; SD: 11.6) who died on an acute or intensive care unit across 121 VAMCs between October 2010 and September 2015. Mediation analyses were used to assess whether five care processes (potentially burdensome transitions, high-intensity EOL treatment, and the BFS factors of Care and Communication, Emotional and Spiritual Support, and Death Benefits) significantly affected the association between Veteran race/ethnicity and a poor/fair BFS overall rating.

Results:

Potentially burdensome transitions, high-intensity EOL treatment, and the three BFS factors of Care and Communication, Emotional and Spiritual Support, and Death Benefits did not substantially mediate the relationship between Veteran race/ethnicity and poor/fair overall ratings of quality of EOL care by bereaved family members.

Conclusions:

The reasons underlying poorer ratings of quality of EOL care among bereaved family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans remain largely unexplained. More research on identifying potential mechanisms, including experiences of racism, and the unique EOL care needs of racial and ethnic minority Veterans and their families is warranted.

Keywords: disparities, end-of-life, Veterans

INTRODUCTION

As the Veteran population grows in age and diversity, the delivery of high-quality and equitable end-of-life (EOL) care is a priority of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 This objective, however, is not without challenges. Since 2012, VA has used the Bereaved Family Survey (BFS) to monitor the quality of EOL care provided to Veterans in VA medical centers (VAMCs), community living centers (i.e., VA nursing homes), and inpatient hospice units. A prior analysis of these data revealed that bereaved family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans were significantly less likely to report excellent overall care during the last month of life than families of White Veterans.2 The largest difference was observed among families of Black Veterans, who were nearly half as likely as their White counterparts to provide an excellent rating. These findings persisted despite the same access and receipt of VA palliative care and inpatient hospice services – two care processes that have been linked to higher ratings of EOL care in culturally diverse samples of Veterans.3,4 Thus, it is critical to explore and identify other care processes that contribute to racial/ethnic differences in bereaved family ratings.

Frequent care transitions and receipt of high-intensity EOL treatment represent two objective care processes that warrant examination. Frequent care transitions at EOL have been deemed “potentially burdensome” to patients and families by researchers.5,6 Potentially burdensome transitions, including hospital admission in the days leading up to death or multiple hospitalizations in the last few months of life, are common, especially among older racial/ethnic minority patients.6,7 Black and Hispanic patients are also more likely to receive life-prolonging treatment near EOL, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation.8 Two large studies have linked these care processes to lower family ratings of EOL care quality. Ersek and colleagues9 found that receipt of aggressive EOL treatment was linked to poorer BFS outcomes in a diverse sample of Veterans with advanced lung cancer. In a separate study of Medicare-enrolled decedents, Makaroun et al.10 documented an association between frequent transitions near EOL with lower overall ratings of care by families. Although both studies were conducted using large representative samples, results were not stratified by race/ethnicity. To our knowledge, only one study has examined the interplay of race/ethnicity, high-intensity EOL treatment, and bereaved family ratings of care. In a study of 15 intensive care units (ICUs), Lee and colleagues11 found that receipt of high intensity treatments at EOL partially mediated the relationship between race/ethnicity and bereaved family ratings of the quality of dying. However, the analysis did not examine race and ethnicity independently, thus limiting opportunities to inform culturally tailored interventions.

In addition to the medical record, the BFS can also be used to measure EOL care processes. These processes are captured on three established BFS factors related to the quality of care and communication, provision of emotional and spiritual support, and receipt of death benefit information.12 Although all three factors are significant predictors of the BFS overall rating,13 racial/ethnic differences on the BFS factor scores have not been assessed. It is plausible that racial/ethnic differences in the perceptions of specific care processes measured by the BFS could explain some of the observed differences on the overall rating.

The objective of this study was to examine whether racial/ethnic differences in a set of EOL care process measures identified via the Veteran’s medical record (i.e., potentially burdensome transitions, high-intensity EOL treatment) and BFS evaluations (i.e., Care and Communication, Emotional and Spiritual Support, and Death Benefits factors) were present, and if so, whether they mediated the relationship between Veteran race/ethnicity and bereaved families’ overall rating of care. Our overarching hypothesis was that these EOL care processes would mediate the relationship between Veteran race/ethnicity and a poor/fair BFS overall rating. We focused our analysis on deaths occurring in acute care settings (i.e., medical/surgical units and ICU) because these venues may pose the highest risk to racial/ethnic minority patients of receiving care not consistent with their preferences.14,15

METHODS

Data sources

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of three linked data sources from October 2010 through September 2015. VA’s Clinical Data Warehouse (CDW), a repository of clinical, administrative, and financial data, was used to obtain information on Veteran demographics, clinical conditions and procedures, consultations, unit type, dates of admission/discharge, and death. The Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center files provided information about facility characteristics. Finally, BFS data were collected by the Veteran Experience Center as part of their operational mission. The BFS instrument has strong psychometric properties12,16,17 and includes 17 forced-choice items that ask the Veteran’s next-of-kin (NOK) to report on the care experienced by the Veteran and family during the last month of life. Between 4 and 6 weeks following the Veteran’s death, the NOK is contacted and asked to participate in the BFS via mail, online, or phone.18 Measurement invariance has been established across survey modes.12 The average response rate across the study period was 56% and ranged from 50% to 65% across years. Prior work by Smith et al.19 found that nonresponse was more likely among NOK of younger and racial/ethnic minority Veterans; therefore, we applied adjustments for nonresponse bias in our models. Hotdeck imputation procedures were used to complete missing BFS items that ranged from 2% to 14%.20 This study was approved by the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Sample

The sample included Veterans who died on a medical/surgical unit or ICU in any VAMC nationally during the study period and whose NOK completed a BFS. We further limited our sample to Veterans who were identified in the medical record as one of three racial/ethnic categories based on data provided in CDW: non-Hispanic White (i.e., White), non-Hispanic Black (i.e., Black), and Hispanic. Other racial/ethnic groups were excluded from this analysis due to small sample sizes and poor data reliability.21

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome was the BFS global item that asks the respondent to rate the overall quality of care received by the Veteran in the last month of life. The item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “poor” to “excellent” care received. Responses were dichotomized as “poor” or “fair” versus all other responses for the analysis.

Potential mediator variables

Five potential mediator variables measuring EOL care processes were selected a-priori for examination: burdensome transitions; high-intensity EOL treatment; Care and Communication; Emotional and Spiritual Support; and Death Benefits. Each mediator construct is described in further detail below. Variables required to create the potentially burdensome transition and high-intensity EOL treatment measures were obtained from CDW. A transition was considered potentially burdensome (yes/no) if: (1) the Veteran’s final hospital admission (during which the patient died) occurred three or fewer days prior to death, or (2) the Veteran was hospitalized three or more times during the last 90 days of life.5,6 High-intensity EOL treatment (yes/no) was defined as receipt of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, indicated by the presence of ICD-9 codes 99.60 or 99.63, and/or mechanical ventilation, indicated by ICD-9 codes 96.04, 96.05, or 96.7×, within the last week of life followed by death in the ICU.22

Other potential mediators included the three psychometrically established BFS factors: Care and Communication (5 items, i.e., staff listened to concerns; staff provided medical treatment that the Veteran wanted; staff were kind, caring, and respectful; staff kept family members informed about Veteran’s condition; staff attended to personal care needs), Emotional and Spiritual Support (3 items, i.e., staff gave enough emotional support before death; staff gave enough emotional support after death; staff gave enough spiritual support), and Death Benefits (3 items, i.e., staff gave enough information about survivor’s benefits; staff gave enough information about burial and memorial benefits; staff gave enough help with funeral arrangements). Items composing the Care and Communication and Emotional and Spiritual Support factors were scored on 4-point Likert-type scales ranging from “always” (scored as 3) to “never” (scored as 0). The Death Benefits factor items were scored as dichotomous (yes/no) responses. The three factor scores were calculated as the sum of the individual item scores composing each factor. Each factor score was dichotomized as above/below the median for ease of interpretation in the mediation analysis.

Covariates

Covariates included Veteran age, sex, primary diagnosis for final admission using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software23 categories, medical comorbidities as defined by Elixhauser24 for the year prior to death, and relationship of the BFS respondent to the Veteran (e.g., spouse). We also accounted for whether a palliative care consult was received in the last 90 days of life. Facility-level structural characteristics included: location (rural/urban); region (Northeast, South, Midwest, Mountain, West) based on the Veteran Integrated Service Network classification system; and facility complexity (high, moderate, low). VA facility complexity is an administrative categorization based on factors such as patient volume, clinical services, and teaching affiliations. We included these variables as covariates to account for their independent effects on BFS ratings.2,25 Inverse probability weights were used in models to account for BFS nonresponse.19

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for sample characteristics, potential mediators and the BFS overall EOL care rating outcome by race/ethnicity. χ2 tests and ANOVA were used to test for statistically significant differences in categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

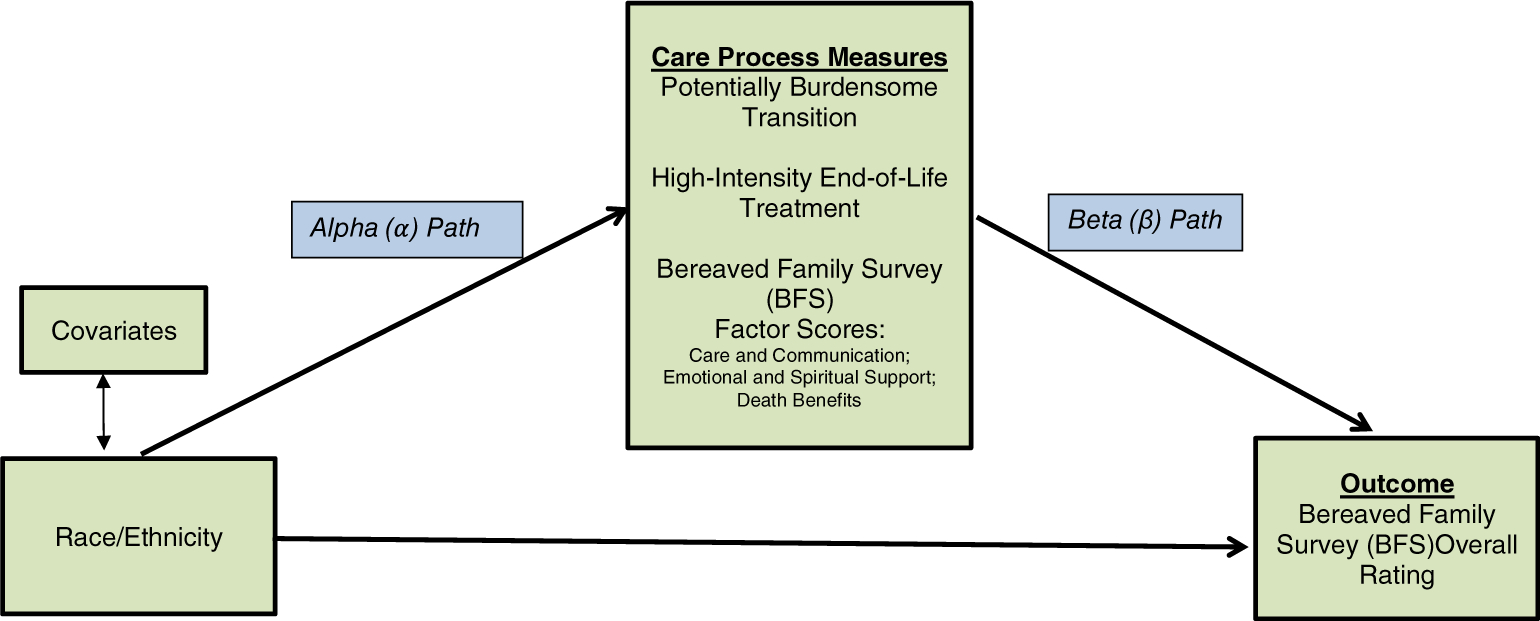

A “product of coefficients” approach26 was used to assess whether any potential mediator significantly affected the association between Veteran race/ethnicity and the BFS overall rating (see Figure 1). Separate mediation analyses were conducted for Veteran race (i.e., comparing White to Black Veterans) and ethnicity (i.e., comparing White to Hispanic Veterans). Broadly, for any observed association between the overall rating and race/ethnicity, our mediation analysis was conducted to investigate and quantify which, if any, mediator might explain those observed associations. We employed a logistic (e.g., logit link) generalized linear mixed modeling approach to separately estimate two direct effects: the α path (i.e., the effect of race/ethnicity on the mediator variable) and the β path (i.e., the effect of the mediator variable on a poor/fair overall rating). Additionally, models included adjustment for covariates (to control for potential confounding) and random intercepts for each VAMC (to control for clustering). The indirect, or mediated, effect was calculated by taking the product of the log odds coefficients (αβ) obtained from the α and β paths and bootstrapping was used to calculate 95% asymmetric confidence limits (ACLs).27,28 We then quantified the portion of the total effect of race/ethnicity on an overall poor/fair rating that was attributed to each mediator (i.e., the proportion mediated). The proportion mediated was calculated as the ratio of (1) the indirect/mediated effect to (2) the total effect of race/ethnicity on an overall poor/fair rating that was calculated from a simple model with these constructs. For ease of interpretation, we expressed the resulting proportion as a positive or negative percentage (%). Positive % mediated estimates reflect instances where the mediators enhanced the impact of race/ethnicity on overall poor/fair ratings and negative % mediated estimates reflect instances where the mediators diminished the impact. Estimated model coefficients were converted to average predicted probabilities and associated 95% CIs for each level of the independent variables in the α (i.e., race/ethnicity) and β (i.e., mediator variables) path models to aid in assessing the mediator effects.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model of the relationships between race/ethnicity, EOL care processes, and BFS outcomes

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine whether the tested mediators exerted different effects among older and younger adults given that Veterans of all ages were included in our sample. Specifically, we stratified each racial and ethnic mediation analysis by age, first examining the relationships among Veterans aged 65 years and older at the time of death, and then among those younger than age 65. SAS Enterprise Guide v.7.14 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for the analysis.

RESULTS

The sample included 17,911 Veterans who died in one of 121 VAMCs, of whom 77.0% were White, 19.2% were Black, and 3.8% were Hispanic. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of Veterans for the full sample and by racial/ethnic group. Average age at time of death was 73.7 years. Statistically significant differences were noted by race/ethnicity in all characteristics except for sex.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sample by veteran race/ethnicity

| Total sample, n = 17,911 | Non-Hispanic, White n = 13,792 | Non-Hispanic Black, n = 3445 | Hispanic, n = 674 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 73.7 ± 11.6 | 74.5 ± 11.3 | 71.0 ± 12.0 | 71.4 ± 12.5 | <0.001 |

| ≥ age 65, n (%) | 13,399 (74.8) | 10,731 (77.9) | 2227 (64.4) | 441 (65.4) | <0.001 |

| < age 65, n (%) | 4512 (25.2) | 3061 (22.2) | 1218 (35.4) | 233 (34.6) | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 17,555 (98.0) | 13,527 (98.1) | 3365 (97.7) | 663 (98.4) | 0.26 |

| Next of kin relationship, n (%) | |||||

| Spouse | 8513 (47.5) | 6731 (48.8) | 1446 (42.0) | 336 (49.9) | <0.001 |

| Child | 4923 (27.5) | 3860 (28.0) | 885 (25.7) | 178 (26.4) | |

| Sibling | 2245 (12.5) | 1566 (11.4) | 599 (17.4) | 80(11.9) | |

| Other family | 1385 (7.7) | 957 (6.9) | 372 (10.8) | 56 (8.3) | |

| Other non-family | 845 (4.7) | 678 (4.9) | 143 (4.2) | 24 (3.6) | |

| Primary diagnosis (most common), n (%) | |||||

| Respiratory | 4003 (22.4) | 3288 (23.8) | 591 (17.2) | 124 (18.4) | <0.001 |

| Circulatory | 3258 (18.2) | 2520 (18.3) | 611 (17.7) | 127 (18.8) | 0.69 |

| Cancer | 2792 (15.6) | 2080 (15.1) | 632 (18.4) | 80(11.9) | <0.001 |

| Infection | 2508 (14.0) | 1840 (13.3) | 554(16.1) | 114(16.9) | <0.001 |

| Digestive | 1562 (8.7) | 1195 (8.7) | 276 (8.0) | 91 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Palliative care consult within 90 days of death, n (%) | 6900 (38.5) | 5255 (38.1) | 1403 (40.7) | 242 (35.9) | 0.01 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, mean ± SD | 8.0 ± 3.0 | 7.9 ± 3.0 | 8.2 ± 3.0 | 8.2 ± 3.1 | <0.001 |

| VAMC complexity level, n (%) | |||||

| Level 1a, 1b, 1c | 15,815 (88.3) | 11,876 (86.1) | 3323 (96.5) | 616 (91.4) | <0.001 |

| Level 2, 3 | 2096 (11.7) | 1916 (13.9) | 122 (3.5) | 58 (8.6) | |

| VAMC urban/rural classification, n (%) | |||||

| Urban | 17,063 (95.3) | 12,973 (94.1) | 3421 (99.3) | 669 (99.3) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 848 (4.7) | 819 (5.9) | 24 (0.7) | 5 (0.7) | |

| Region, n (%) | |||||

| Northeast | 2889 (16.1) | 2346 (17.0) | 456 (13.2) | 87 (12.9) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 3380 (18.9) | 2814 (20.4) | 533 (15.5) | 33 (4.9) | |

| South | 8772 (49.0) | 6345 (46.0) | 2178 (63.2) | 249 (36.9) | |

| West | 2870 (16.0) | 2287 (16.6) | 278(8.1) | 305 (45.3) |

Note: p-values determined using χ2 for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Abbreviation: VAMC, Veterans Affairs medical center.

Table 2 describes the primary outcome of the poor/fair overall rating and tested mediators by Veteran race/ethnicity. Significantly higher percentages of bereaved families of Black (14.2%) and Hispanic (13.8%) Veterans gave a poor/fair overall rating compared with families of White Veterans (9.0%, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences by race/ethnicity in frequency of potentially burdensome transitions. Hispanic (26.1%) and Black (22.4%) Veterans were significantly more likely than White Veterans (18.2%) to receive high-intensity EOL treatment (p < 0.001). Bereaved family members of Black and Hispanic Veterans had significantly lower mean scores and were less likely to score above the median on the BFS factors of Emotional and Spiritual Support and Death Benefits compared with families of White Veterans.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of BFS outcome and tested process of care mediators by veteran race/ethnicity

| Total sample, n = 17,911 | Non-Hispanic White, n = 13,792 | Non-Hispanic Black, n = 3445 | Hispanic, n = 674 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | |||||

| Poor/fair overall BFS rating, n (%) | 1824 (10.2) | 1241 (9.0) | 490 (14.2) | 93 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Tested mediators | |||||

| EOL care processes | |||||

| Potentially burdensome transition, n (%) | 6438 (35.9) | 4989 (36.2) | 1189 (34.5) | 260 (38.6) | 0.07 |

| High-intensity EOL treatment, n (%) | 3459 (19.3) | 2512 (18.2) | 771 (22.4) | 176 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| BFS factors | |||||

| Care and Communication, mean ± SD | 13.0 ± 2.8 | 13.0 ± 2.7 | 12.8 ± 3.0 | 12.9 ± 2.9 | <0.001 |

| Score ≥ median (14), n (%) | 10,568 (59.0) | 8195 (59.4) | 1970 (57.2) | 403 (59.8) | 0.05 |

| Emotional and Spiritual Support, mean ± SD | 6.8 ± 2.6 | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 6.3 ± 2.8 | 6.6 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Score ≥ median (8), % | 9602 (53.6) | 7743 (56.1) | 1510 (43.8) | 349 (51.8) | <0.001 |

| Death Benefits, mean ± SD | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Score ≥ median (2), % | 9725 (54.3) | 7981 (57.9) | 1441 (41.8) | 303 (45.0) | <0.001 |

Note: p values determined using χ2 for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. Theoretical range for BFS subscales: Care and Communication (0–15); Emotional and Spiritual Support (0–9), and Benefits (0–3).

Abbreviation: EOL, end-of-life.

Table 3 displays the results of the mediation analysis for Black Veteran race. In adjusted models assessing the relationship between race and each potential mediator (alpha [α] path), significant associations were observed between Black race and receipt of high-intensity EOL treatment as well as the three BFS factor scores. The fitted models indicated a higher predicted probability of Black Veterans receiving high-intensity EOL treatment (0.22, 95% CI = 0.15, 0.29) compared with their White counterparts (0.18, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.25). Compared with White Veterans, bereaved family members of Black Veterans scored below the median on all three BFS factors, with estimated differences in predicted probabilities of 0.02 for Care and Communication, 0.12 for Emotional and Spiritual Support, and 0.16 for Death Benefits. Although potentially burdensome transitions did not mediate the relationship between race and the BFS overall rating, a small but statistically significant mediation effect was detected for high-intensity EOL treatment (αβ = 0.03, 95% ACL = 0.01, 0.05, % mediated effect = 0.1%). Slightly larger mediation effects were noted for all three BFS factors: Care and Communication (αβ = −0.26, 95% ACL = −0.47, −0.06, % mediated effect = −0.8%), Emotional and Spiritual Support (αβ = 1.11, 95% ACL = 0.95, 1.27, % mediated effect = 3.5%), and Death Benefits (αβ = 0.52, 95% ACL = 0.46, 0.59, % mediated effect = 1.7%). In summary, Care and Communication slightly diminished the effect of race on a poor/fair overall rating, whereas high intensity EOL treatment, Emotional and Spiritual Support, and Death Benefits slightly amplified the effect.

TABLE 3.

Assessing mediation effects of care processes on the relationship between race and overall poor/fair rating on BFS (n = 17,217)

| Alpha path (α): Effect of race on mediator |

Beta path (β): Effect of mediator on poor/fair overall rating |

Mediated effect (αβ) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | α (SE) | Predicted probability (95% CI) | β (SE) | Predicted probability (95% CI) | αβ (95% ACL) | % Mediated effect | |

| Potentially burdensome transition | −0.01 (0.03) |

0.07 (0.04) |

−0.001 (−0.01 to 0.00) | 0 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.35 (0.29 to 0.40) | Burdensome transition | 0.11(0.03 to 0.18) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.36 (0.30 to 0.42) | No burdensome transition | 0.10(0.03 to 0.17) | ||||

| High-intensity EOL treatment | 0.17 (0.04)*** |

0.16 (0.04)*** |

0.03 (0.01 to 0.05)** | 0.1 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.29) | Intense EOL treatment | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.21) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.18(0.11 to 0.25) | No intense EOL treatment | 0.09 (0.01 to 0.18) | ||||

| BFS Factor: Care and Communication score (≥median) | 0.07 (0.03)** |

−3.66 (0.08)*** |

−0.26 (−0.47 to −0.06)** | −0.8 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.57 (0.52 to 0.63) | High Care and Communication score | 0.01(0.00 to 0.17) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.59 (0.54 to 0.65) | Low Care and Communication score | 0.23 (0.08 to 0.39) | ||||

| BFS factor: Emotional and Spiritual Support score (≥median) | −0.40 (0.03)*** |

−2.79 (0.06)*** |

1.11 (0.95 to 1.27)*** | 3.5 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.44 (0.39 to 0.50) | High Emotional and Spiritual Support score | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.14) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.56 (0.51 to 0.62) | Low Emotional and Spiritual Support score | 0.20 (0.08 to 0.32) | ||||

| BFS Factor: Death Benefits score (≥median) | −0.55 (0.03)*** |

−0.94 (0.04)*** |

0.52 (0.46 to 0.59)*** | 1.7 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.42 (0.36 to 0.47) | High Death Benefits score | 0.06 (0.00 to 0.13) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.58 (0.52 to 0.63) | Low Death Benefits score | 0.15 (0.08 to 0.22) | ||||

Note: Negative predicted probabilities have been truncated to 0. High/low BFS factor scores (Care and Communication; Emotional and Spiritual Support, Death Benefits) determined in relation to median (high=≥median; low=<median).

p ≤ 0.01

p ≤ 0.001.

Table 4 presents the results of the mediation analysis for Veteran ethnicity. Compared with White Veterans, Hispanic Veterans had a higher predicted probability of experiencing a potentially burdensome transition (0.36, 95% CI = 0.25, 0.47 vs 0.39, 95% CI = 0.27, 0.50) and of receiving high-intensity EOL treatment (0.18, 95% CI = 0.05, 0.32 vs 0.26, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.39). Compared with families of White Veterans, families of Hispanic Veterans had lower predicted probabilities of scoring above the median on the Care and Communication (0.58, 95% CI = 0.47, 0.70 vs 0.60, 95% CI = 0.48, 0.71) and Death Benefits (0.45, 95% CI = 0.34, 0.56 vs 0.58, 95% CI = 0.47, 0.69) factors. Three tested process variables exhibited small, but statistically significant, mediation effects on the relationship between Hispanic Veteran ethnicity and a poor/fair overall BFS rating: a potentially burdensome transition (αβ = 0.02, 95% ACL = 0.00, 0.04, % mediated effect = 0.1%) and Death Benefits (αβ = 0.40, 95% ACL = 0.29, 0.51, % mediated effect = 1.5%) slightly amplified the association, whereas Care and Communication diminished the association (αβ = −0.50, 95% ACL = −0.93,−0.07, % mediated effect = −1.9%). The sensitivity analysis that stratified the race and ethnicity mediation models by age demonstrated similar patterns and effects for older (≥age 65) and younger (< age 65) Veterans.

TABLE 4.

Assessing mediation effects of care processes on the relationship between ethnicity and BFS overall poor/fair rating (n = 14,443)

| Alpha path (α): effect of ethnicity on mediator |

Beta path (β): effect of mediator on poor/fair overall rating |

Mediated effect (αβ) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | α (SE) | Predicted probability (95% CI) | β (SE) | Predicted probability (95% CI) | αβ (95% ACL) | % Mediated effect | |

| Potentially burdensome transition | 0.15 (0.06)** | 0.13 (0.04)** | 0.02 (0.000 to 0.04)* | 0.1 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.39 (0.27 to 0.50) | Burdensome transition | 0.10(0.02 to 0.18) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.36 (0.25 to 0.47) | No burdensome transition | 0.09 (0.01 to 0.17) | ||||

| High-intensity EOL treatment | 0.16 (0.07)* | 0.13 (0.05)** | 0.02 (−0.003 to 0.04) | 0.1 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.26 (0.13 to 0.39) | Intense EOL treatment | 0.12(0.02 to 0.22) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.18(0.05 to 0.32) | No intense EOL treatment | 0.09 (0.00 to 0.18) | ||||

| BFS factor: Care and Communication score (≥median) | 0.13 (0.06)* | −3.89 (0.10)*** | −0.50 (−0.93 to −0.07)* | −1.9 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.70) | High Care and Communication score | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.21) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.60 (0.48 to 0.71) | Low Care and Communication score | 0.22 (0.02 to 0.42) | ||||

| BFS factor: Emotional and Spiritual Support score (≥median) | −0.06 (0.06) | −2.87 (0.07)*** | 0.16 (−0.15 to 0.48) | 0.6 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.51 (0.40 to 0.62) | High Emotional and Spiritual Support score | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.15) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.56 (0.45 to 0.67) | Low Emotional and Spiritual Support score | 0.19(0.05 to 0.33) | ||||

| BFS factor: Death Benefits score (≥median) | −0.42 (0.06)*** | −0.95 (0.04)*** | 0.40 (0.29 to 0.51)*** | 1.5 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.45 (0.34 to 0.56) | High Death Benefits score | 0.06 (0.00 to 0.14) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.69) | Low Death Benefits score | 0.14(0.06 to 0.22) | ||||

Note: Negative predicted probabilities have been truncated to 0. High/low BFS factor scores (Care and Communication; Emotional and Spiritual Support, Death Benefits) determined in relation to median (high = ≥median; low = < median).

p ≤ 0.05

p ≤ 0.01

p ≤ 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Contrary to our study’s hypothesis, we found that five care processes associated with EOL care quality, including potentially burdensome transitions, receipt of high-intensity EOL treatment, and three BFS factor scores related to specific aspects of EOL care, mediated little to none of the relationship between Veteran race/ethnicity and poor/fair overall ratings of EOL care among their bereaved family members. Overall, the results suggest that observed disparities in overall ratings of EOL care among bereaved family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans may be largely independent of these measures and demonstrate the need for more research.

We found that Black and Hispanic Veterans were more likely to receive high-intensity EOL treatment, and that Hispanic patients had a higher probability of experiencing a potentially burdensome transition, largely affirming other studies conducted outside VA.6–8,29 However, these care processes demonstrated negligible mediation of the relationship between race/ethnicity and poor/fair overall ratings. This finding offers a countering narrative to literature suggesting that greater care utilization near EOL among racial/ethnic minority patients may be indicative of poorer quality of care.11,29 Rather, the lack of mediation suggests that these specific EOL care processes may have been preferred by the Veteran and/or family, and subsequently were not viewed as excessive or burdensome care that resulted in negative ratings. Research has documented that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely than White patients to prefer life-sustaining treatments and receive more care near EOL.30 What has remained unclear is whether this relationship is disparities-based and driven by factors such as mistrust of the healthcare system and poor communication between healthcare staff and patients/families, or by differences in personal preferences, cultural values, and beliefs, including spirituality.31,32 Our results support the latter in demonstrating that receipt of intensive EOL treatment or experiencing multiple transitions near EOL did not explain poorer ratings of overall EOL care among family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans.

Among the EOL care processes measured by the BFS, we found that some acted as weak mediators of the relationship between race/ethnicity and poor/fair overall EOL care ratings. The largest mediation effect of the relationship between Veteran race and a poor/fair overall rating was observed for the BFS factor of Emotional and Spiritual Support (% mediated effect = 3.5%). This finding supports prior studies that have described the importance of learning and providing for the emotional- and faith-related needs of members of Black and African American communities in EOL care situations.33,34 In our analysis of Veteran ethnicity, the Death Benefits factor demonstrated the largest % mediated effect (1.5%) of a poor/fair overall rating and points to implications for how benefits information is communicated to family members of Hispanic Veterans after the Veteran’s death. Language barriers, such as limited English proficiency and incongruent translation of benefits materials, may be a potential source of these differences.35,36 Although we identified that these BFS factors were contributors to the relationship between race/ethnicity and overall poor/fair ratings, the mediation effects were small. Thus, expectations for the impact of interventions related to these factors alone to reduce racial/ethnic differences in overall ratings should be tempered. Assuming the % mediated effects are summative, over 95% of the racial and ethnic differences in overall ratings were not explained by the tested mediators.

We recognize limitations to our approach. Due to the observational nature of our inquiry, we cannot claim that the relationships are causal. Racial/ethnic differences in how bereaved families of Veterans rate the overall quality of EOL care remain largely unexplained which strongly suggests that important measures were omitted from our models. For example, we did not account for the presence and content of advance directives or goals-of-care conversations. Use of data from VA’s Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative, a national effort focused on improving the completion and documentation of goals-of-care conversations for all seriously ill Veterans, may facilitate in-depth assessments of whether treatment was aligned with preferences. Although documentation of these conversations is lower among racial/ethnic minority Veterans nationally,37 a recent study found that African American and Hispanic Veterans enrolled in VA’s Home Based Primary Care program had higher rates of documented life-sustaining treatment decisions compared with their White counterparts.38 As additional measures of EOL care quality are explored that reflect the preferences of racial/ethnic minority Veterans, this program may offer unique insights. We were also unable to measure knowledge regarding EOL care options, another important factor that has been identified as a potential driver of racial/ethnic differences in EOL treatment and quality assessments.39–41

Additional studies are also necessary to illuminate factors currently not measured on the BFS. Although we believe that the BFS captures important aspects of EOL care, such as communication, more refined items may be necessary to understand racial/ethnic disparities in ratings. Qualitative studies that identify the preferences, needs, and experiences surrounding EOL care among racial/ethnic minority Veterans and their families are needed that could be used to create new patient-centered measures. For example, future research could examine how factors such as symptom management, trust in healthcare providers and systems, experiences of racism, and racial/ethnic concordance of patients and care team members near EOL may play a role in EOL quality disparities. Finally, our analysis was limited to the acute care setting. It is possible that these relationships may differ, and disparities be reduced, in more intimate settings such as inpatient hospice units.42

In summary, we found that poorer ratings of overall EOL care among bereaved family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans were not largely explained by frequent care transitions, receipt of high-intensity EOL treatment, or family evaluations of specific EOL care processes. Further research is required to identify the needs and preferences of racial/ethnic minority Veterans near EOL and their families as well as other factors that may contribute to poorer ratings of EOL care to inform the development of culturally sensitive interventions.

Key points.

Family members of Black and Hispanic Veterans are more likely to report poor/fair quality of EOL care than their White counterparts.

Differences in overall ratings of end-of-life (EOL) care by bereaved family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans were not largely explained by frequent care transitions, receipt of high-intensity EOL treatment, or family evaluations of specific EOL care processes.

Why does this paper matter?

Five care processes linked with high-quality EOL care explained very little of the observed differences in overall EOL care quality ratings among bereaved family members of racial/ethnic minority Veterans. More research is needed to identify the source of these differences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge John Cashy for his programming assistance.

SPONSOR’S ROLE

The Department of Veterans Affairs had no role in the design and conduct of the study. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or the U.S. Government.

Funding information

This work was supported by Merit Review Award I01HX002190 from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Final Report of the Commission on Care. 2016. Commission on Care (online). Available from: https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo69908/Commission-on-Care_Final-Report_063016_FOR-WEB.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 2.Kutney-Lee A, Smith D, Thorpe J, Del Rosario C, Ibrahim S, Ersek M. Race/ethnicity and end-of-life care among veterans. Med Care. 2017;55(4):342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, Richardson D. The optimal delivery of palliative care: a national comparison of the outcomes of consultation teams vs inpatient units. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4): 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013; 309(5):470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SY, Hsu SH, Aldridge MD, Cherlin E, Bradley E. Racial differences in health care transitions and hospice use at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(6):619–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Sharma R, et al. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and healthcare intensity at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1308–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ersek M, Miller SC, Wagner TH, et al. Association between aggressive care and bereaved families’ evaluation of end-of-life care for veterans with non-small cell lung cancer who died in veterans affairs facilities. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3186–3194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makaroun LK, Teno JM, Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Gozalo P, Mor V. Late transitions and bereaved family member perceptions of quality of end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(9): 1730–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JJ, Long AC, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. The influence of race/ethnicity and education on family ratings of the quality of dying in the ICU. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(1):9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorpe J, Smith D, Kuzla N, Scott L, Ersek M. Does mode of survey administration matter? Using measurement invariance to validate the mail and phone versions of the bereaved family survey (BFS). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(3):P546–P556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith D, Thorpe JM, Ersek M, Kutney-Lee A. Identifying optimal factor scores on the bereaved family survey: implications for practice and policy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(1):108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1533–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Honoring Preferences Individuality at the End of Life. The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casarett D, Shreve S, Luhrs C, et al. Measuring families’ perceptions of care across a health care system: preliminary experience with the family assessment of treatment at end of life short form (FATE-S). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(6):801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu H, Trancik E, Bailey FA, et al. Families’ perceptions of end-of-life care in veterans affairs versus non-veterans affairs facilities. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(8):991–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veteran Experience Center Methods. 2018. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (online). Available from: https://www.cherp.research.va.gov/PROMISE/vecmethods.asp. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 19.Smith D, Kuzla N, Thorpe J, Scott L, Ersek M. Exploring non-response bias in the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Bereaved Family Survey. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(10):858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andridge RR, Little RJA. A review of hot deck imputation for survey non-response. Int Stat Rev. 2010;78(1):40–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Government Accountability Office (online). VA Healthcare: Opportunities Exist for VA to Better Identify and Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities. GAO Report 20–83. 2019. Available from: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-83.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 22.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(33):5559–5564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (online). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. 2017. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 24.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998; 36(1):8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ersek M, Smith D, Cannuscio C, Richardson DM, Moore D. A nationwide study comparing end-of-life care for men and women veterans. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(7):734–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Meth. 2002;7(1):83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar Behav Res. 2004;39(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairchild AJ, McDaniel HL. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: mediation analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1259–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ornstein KA, Roth DL, Huang J, et al. Evaluation of racial disparities in hospice use and end-of-life treatment intensity in the REGARDS cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2014639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bazargan M, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Disparities in palliative and hospice care and completion of advance care planning and directives among non-Hispanic Blacks: a scoping review of recent literature. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(6):688–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LoPresti MA, Dement F, Gold HT. End-of-life care for people with cancer from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(3):291–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson J, Hayden T, True J, et al. The impact of faith beliefs on perceptions of end-of-life care and decision making among African American church members. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(2):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCleskey SG, Cain CL. Improving end-of-life care for diverse populations: communication, competency, and system supports. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(6):453–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. No easy talk: a mixed methods study of doctor reported barriers to conducting effective end-of-life conversations with diverse patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. Patient-reported barriers to high-quality, end-of-life care: a multiethnic, multilingual, mixed-methods study. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(4):373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levy C, Ersek M, Scott W, et al. Life-sustaining treatment decisions initiative: early implementation results of a national veterans affairs program to honor Veterans’ care preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1803–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy C, Esmaeili A, Smith D, et al. Family members’ experience improves with care preference documentation in home based primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:3576–3583. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhodes RL, Elwood B, Lee SC, Tiro JA, Halm EA, Skinner CS. The desires of their hearts: the multidisciplinary perspectives of African Americans on end-of-life care in the African American community. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(6):510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Connor SR, Teno JM. Bereaved family members’ evaluation of hospice care: what factors influence overall satisfaction with services? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(4):365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhodes RL, Teno JM, Connor SR. African American bereaved family members’ perceptions of the quality of hospice care: lessened disparities, but opportunities to improve remain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(5):472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]