Abstract

In several clonally unrelated VanB-type vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strains, we demonstrated a common physical relationship between pbp5 and Tn5382 as well as common mutations within pbp5. The majority of these strains transferred vancomycin and ampicillin resistance to E. faecium in vitro, suggesting the dissemination of similar transferable pbp5-vanB-containing mobile elements throughout the United States.

Enterococcus faecium strains are resistant to penicillin through the expression of low-affinity penicillin-binding protein PBP5 (9) and are resistant to vancomycin most often through the action of resistance operons encoding VanA and VanB types of resistance (1–3, 8). PBP5-mediated low-level ampicillin resistance has been thought to be intrinsic to the enterococci (and nontransferable), whereas the vancomycin resistance determinants are acquired and transferable.

We recently described the cotransfer of ampicillin and vancomycin resistance within a large, chromosomally located element that possessed the vanB-containing transposon Tn5382 and pbp5 (5). The present study was undertaken to determine whether similar large chromosomal elements were present in enterococci from diverse geographic regions.

Ten clinical E. faecium strains from northeast Ohio, 1 strain from Hawaii, and 12 VanB strains from diverse geographical locations (kindly provided by Fred Tenover of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) were used in these studies. Bacterial strains were grown overnight in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth at 37°C. MICs were determined using dilution on BHI agar for ampicillin and vancomycin in concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 512 μg/ml. One or two concentrations were tested for the following antibiotics: tetracycline (10 μg/ml), erythromycin (10 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (10 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml), streptomycin (2,000 μg/ml), and gentamicin (500 and 2,000 μg/ml).

PCR experiments were carried out using 10 μl of an overnight culture diluted 1:10 in sterile water and heated to 95°C for 10 min. The sample was diluted 1:10 in a previously prepared PCR mixture (Perkin-Elmer) and amplified using a Perkin-Elmer 9600 thermal cycler with Taq DNA polymerase for 25 cycles of denaturation at 95°C (10 s), annealing at 66°C (10 s), and extension at 74°C (1 min 30 s). Primers used to amplify a 1,076-bp product spanning the downstream end of pbp5 and the left end of Tn5382 were 1492 (5′-TCAGCCGATTTGCGACAGGTTATG-3′) and 3206 (5′-TGGGGTGGCGGGTATTAGCAGTAT-3′). DNA sequencing reactions were performed on PCR product templates with the ALF automated sequencing kit and Cy5 indodicarbocyanine dye-labeled primer (Pharmacia LKB). The sequence was determined with the ALFExpress automated sequencer (Pharmacia LKB) and analyzed using the MacDNAsis, version 2.0 (Hitachi, Ltd.), sequence analysis program.

Filter matings were performed using PCR-positive clinical strains as donors and E. faecium GE-1 (Aps Fusr Rifr) (5) as the recipient as previously described (5). Six of the 10 clinical strains from northeast Ohio and all other PCR-positive strains were used as donors. Transconjugants were selected on BHI agar plates containing vancomycin (6 μg/ml), fusidic acid (25 μg/ml), and rifampin (100 μg/ml).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on genomic DNA extracted from overnight cultures using the GenePath Group 1 reagent kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), digested with SmaI as previously described (7), and separated on 1% agarose gels using the enterococcal program on the Bio-Rad GenePath electrophoresis system. Isolates were considered unrelated if they differed by more than five bands. DNA bands separated by PFGE were transferred to nylon filters using the technique of Southern (10). The filter was baked at 80°C for 1 to 2 h, hybridized overnight at 68°C with a digoxigenin-labeled internal vanB probe, and washed under conditions of high stringency according to the specifications of the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). Hybridized fragments were detected using an antidigoxigenin antibody and a chromogenic enzyme substrate (Boehringer Mannheim).

The 1,076-bp product was amplifiable from 10 of 10 clinical strains from northeast Ohio and 6 of 13 strains from diverse geographic locations. Six of the 10 strains from northeast Ohio (chosen because they represented different clonal groups) and the 6 other PCR-positive strains were selected for MIC determination and conjugation experiments. All 12 strains exhibited resistance to high levels of ampicillin and vancomycin and to 10 μg of ciprofloxacin per ml and were susceptible to chloramphenicol (Table 1). Vancomycin resistance was transferred at a low frequency (<10−9/donor CFU) from 7 of the 12 donor strains. All transconjugants expressed resistance to ampicillin and vancomycin at a MIC that was the same as or lower than that for the donor strains (Table 1), a discordance that has been noted previously with transfer of a similar element from E. faecium C68 (5). Transfer of erythromycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline resistance was variable. Neither ciprofloxacin nor gentamicin resistance was transferred.

TABLE 1.

MICs for isolates

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

Origin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | VM | SM | GM | TC | EM | CIP | CM | ||

| GE-1 | <0.5 | <1 | <2,00 | <500 | >10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | Cleveland, Ohio |

| C15 | 512 | >512 | <2,000 | <2,000 | >10 | <10 | >10 | <10 | Cleveland |

| C24 | 256 | 512 | >2,000 | >2,000 | >10 | >10 | >10 | <10 | Cleveland |

| CV174 | 8 | 64 | >2,000 | <500 | <10 | >10 | <10 | <10 | C24 × GE-1 |

| C65 | 512 | 256 | <2,000 | >2,000 | >10 | <10 | >10 | <10 | Cleveland |

| CV183 | 128 | 256 | <2,000 | <500 | >10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | C65 × GE-1 |

| C68 | 512 | 512 | >2,000 | >500 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | Cleveland |

| CV172 | 64 | 512 | <2,000 | <500 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | C68 × GE-1 |

| H11 | 512 | 256 | >2,000 | <500 | >10 | >10 | >10 | <10 | Cleveland |

| CV175 | 32 | 256 | >2,000 | <500 | <10 | >10 | <10 | <10 | H11 × GE-1 |

| Hon1 | 256 | 512 | >2,000 | <500 | <10 | >10 | >10 | <10 | Hawaii |

| CV176 | 64 | 256 | <2,000 | <500 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | Hon1 × GE-1 |

| Mer15 | 256 | 512 | >2,000 | >2,000 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | Cleveland |

| HIPO2863 | 256 | >512 | >2,000 | >2,000 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | Pennsylvania |

| CV177 | 32 | 512 | <2,000 | <500 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 2863 × GE-1 |

| HIPO3174 | 256 | 256 | >2,000 | <500 | <10 | >10 | >10 | <10 | New York |

| HIPO3322 | 128 | >512 | >2,000 | <2,000 | >10 | >10 | >10 | <10 | Ohio |

| HIPO3391 | 128 | 256 | <2,000 | <500 | <10 | >10 | >10 | <10 | Florida |

| HIPO3568 | 256 | 512 | >2,000 | <500 | >10 | >10 | >10 | <10 | Missouri |

| CV178 | 128 | 512 | >2,000 | <500 | >10 | >10 | <10 | <10 | 3568 × GE-1 |

AP, ampicillin; VM, vancomycin; SM, Streptomycin; GM, gentamicin; TC, tetracycline; EM, erythromycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CM, chloramphenicol.

Sequence analysis from all PCR-positive strains revealed five mutations previously identified in the pbp5 gene from E. faecium C68 (GenBank accession number AF117609). Using the numbering system for the pbp5 gene described for E. faecium strain D63r in reference 14, these changes include an additional serine at amino acid position 466 and four additional nucleotide changes (T-1918-C, T-1912-G, C-1899-T, and A-1884-C).

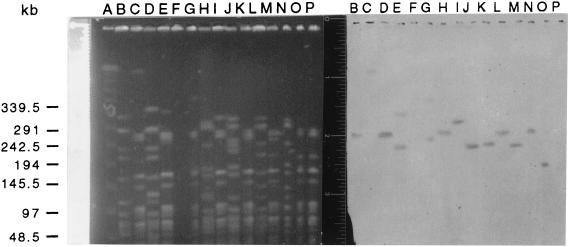

PFGE analysis of the seven strains from which transconjugants were obtained confirmed that the strains were not clonally related (Fig. 1). Southern transfers of the PFGE separation revealed hybridization of vanB probes to large fragments in each of the donors and transconjugants (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

(Right) PFGE of donors and their respective transconjugants. Transconjugants have designations beginning with CV. Lane A, molecular size ladder; lane B, C24; lane C, CV174; lane D, C65; lane E, CV183; lane F, C68; lane G, CV172; lane H, H11; lane I, CV175; lane J, HON1; lane K, CV176; lane L, 2863; lane M, CV177; lane N, 3568; lane O, CV178; lane P, GE-1. (Left) Southern transfer of DNA in a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel hybridized with a vanB probe; lanes follow the order above.

Among the more interesting, and as yet unexplained, attributes of the ongoing outbreaks of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in the United States is the almost exclusive occurrence of this phenotype in E. faecium strains expressing high levels of ampicillin resistance. The coexpression of these resistance phenotypes has significant clinical implications, most prominently the potential for selection of resistant strains with different antibiotics. It has been noted that restriction of vancomycin usage does not consistently affect the overall prevalence of VRE within institutions. This observation is understandable if antibiotic selective pressure persists despite reductions in vancomycin use. Extended-spectrum cephalosporins were observed to select for colonization by ampicillin-resistant E. faecium even before the VRE outbreak (6) and have been associated in several studies with infection or colonization by VRE (4, 7, 11, 12).

The data presented in this paper suggest that the close association of the vancomycin and ampicillin resistance phenotypes, at least in VanB-type VRE, is explainable by their inclusion within large, transferable genetic elements. The precise relationship between pbp5 and Tn5382 demonstrated in different strains by these studies and the presence of the same point mutations within the pbp5 genes suggest that all of these elements evolved from a single genetic event. The nature of this event remains obscure, but it most likely involved the insertion of Tn5382 into a larger, mobile element that encodes PBP5-mediated ampicillin resistance. Although pbp5 has previously been described as transferable on a plasmid (13), evidence for the geographic dispersion of a chromosomally located element possessing Tn5382 and pbp5 has been lacking. It is likely that enterococci only recently acquired this gene or that prior attempts to demonstrate transfer were thwarted by the variable expression of ampicillin resistance in the transconjugants. In fact, we were unable to select directly for transfer of ampicillin resistance. Rather, we noted the variable expression of ampicillin resistance (despite the presence of the pbp5 gene) in transconjugants selected for the transfer of resistance to vancomycin. Further characterization of these large, transferable elements promises to provide significant insight into the evolution of multiresistance in nosocomial enterococci.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs (L.B.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Molinas C, Courvalin P. The VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system controls synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2582–2591. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2582-2591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur M, Molinas C, Depardieu F, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1546, a Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:117–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.117-127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur M, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonten M J M, Slaughter S, Ambergen A W, Hayden M K, van Voorhis J, Nathan C, Weinstein R A. The role of “colonization pressure” in the spread of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1127–1132. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carias L L, Rudin S D, Donskey C J, Rice L B. Genetic linkage and cotransfer of a novel, vanB-containing transposon (Tn5382) and a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 5 gene in a clinical vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4426–4434. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4426-4434.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chirurgi V A, Oster S E, Goldberg A A, McCabe R E. Nosocomial acquisition of β-lactamase-negative, ampicillin-resistant enterococcus. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1457–1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donskey C J, Schreiber J R, Jacobs M R, Shekar R, Smith F, Gordon S, Salata R A, Whalen C, Rice L B. A polyclonal outbreak of predominantly VanB vancomycin-resistant enterococci in northeast Ohio. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:573–579. doi: 10.1086/598636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evers S, Courvalin P. Regulation of VanB-type vancomycin resistance gene expression by the VanSB-VanRB two-component regulatory system in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1302–1309. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1302-1309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontana R, Cerini R, Longoni P, Grossato A, Canepari P. Identification of a streptococcal penicillin-binding protein that reacts very slowly with penicillin. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1343–1350. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1343-1350.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. pp. 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno F, Grota P, Crisp C, Magnon K, Melcher G P, Jorgensen J H, Patterson J E. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium during its emergence in a city in southern Texas. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1234–1237. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.5.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quale J, Landman D, Saurina G, Atwood E, DiTore V, Patel K. Manipulation of a hospital antimicrobial formulary to control an outbreak of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1020–1025. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raze D, Dardenne O, Hallut S, Martinez-Bueno M, Coyette J, Ghuysen J-M. The gene encoding the low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 3r in Enterococcus hirae S185R is borne on a plasmid carrying other antibiotic resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:534–539. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zorzi W, Zhou X Y, Dardenne O, Lamotte J, Raze D, Pierre J, Gutmann L, Coyette J. Structure of the low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 5 PBP5fm in wild-type and highly penicillin-resistant strains of Enterococcus faecium. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4948–4957. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4948-4957.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]