Abstract

The symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi improves plants’ nutrient uptake. During this process, transcription factors have been highlighted to play crucial roles. Members of the GRAS transcription factor gene family have been reported involved in AM symbiosis, but little is known about SCARECROW-LIKE3 (SCL3) genes belonging to this family in Lotus japonicus. In this study, 67 LjGRAS genes were identified from the L. japonicus genome, seven of which were clustered in the SCL3 group. Three of the seven LjGRAS genes expression levels were upregulated by AM fungal inoculation, and our biochemical results showed that the expression of LjGRAS36 was specifically induced by AM colonization. Functional loss of LjGRAS36 in mutant ljgras36 plants exhibited a significantly reduced mycorrhizal colonization rate and arbuscular size. Transcriptome analysis showed a deficiency of LjGRAS36 led to the dysregulation of the gibberellic acid signal pathway associated with AM symbiosis. Together, this study provides important insights for understanding the important potential function of SCL3 genes in regulating AM symbiotic development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-022-01161-z.

Keywords: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, Symbiosis, SCL3, Gibberellic acid signal pathway, Lotus japonicus

Introduction

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi can ubiquitously form symbionts with the vast majority (70%~90%) of terrestrial plants (Harrison 2005). The extensive extracellular mycelium network of AM fungi greatly helps plants to obtain nutrients and water, and in return, the plants provide the fungi with photoassimilates (Harrison 2005). Mycorrhizal colonization often increases grain yield and enhances plant tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses (Fiorilli et al. 2018; Lenoir et al. 2016; Song et al. 2015). For biotic stresses, AM symbiosis enhances plant resistance to a variety of pathogens, including fungi, oomycetes, and parasitic nematodes (Harrier and Watson 2004; Vos et al. 2013; Whipps 2004). For abiotic stresses, AM fungi can significantly improve the resistance of host plants to salinity (Ruiz-Lozano et al. 2018), drought (Ruiz-Lozano et al. 2016), cold (Chen et al. 2013), heat (Gavito et al. 2005), and heavy metal contamination (Glassman and Casper 2012). Several underlying mechanisms of mycorrhizal development have been characterized in model plants, such as Medicago truncatula, Lotus japonicus, and rice (Oryza sativa) (Floss et al. 2013; Park et al. 2015; Lota et al. 2013; Xue et al. 2015; Pimprikar et al. 2016; Gutjahr et al. 2008; Choi et al. 2020).

Transcription factors (TFs) in plants have been highlighted to play important roles in AM symbiosis (Xue et al. 2015). The most notable is that many symbiosis-related TFs belong to GRAS (GIBBERELLIC ACID INSENSITIVE (GAI), REPRESSOR of GAI (RGA), and SCARECROW (SCR)) family (Xue et al. 2015). The C-terminus of GRAS proteins are highly conserved and typically contain five motifs: Leucine heptad repeat I (LHRI), Leucine heptad repeat II (LHRII), VHIID, PFYRE, and SAW (Bolle 2004; Tian et al. 2004). However, the N-terminus of GRAS proteins are variable, which may determine the functional specificity of these proteins (Bolle 2004; Sun et al. 2011; Tian et al. 2004). Members of the GRAS gene family have been identified in several plants ranging from 33 to 106, including Arabidopsis, rice, Populus, Chinese cabbage, Prunus mume, and tomato (Huang et al. 2015; Liu and Widmer 2014; Lu et al. 2015; Song et al. 2014; Tian et al. 2004). GRAS gene family is further categorized into different subfamilies in different plants, ranging from 8 to 17 subfamilies (Huang et al. 2015) (Cenci and Rouard 2017; Tian et al. 2004; Xu et al. 2016).

GRAS family TFs function in a number biological processes including signal transduction, axillary shoot meristem formation, root radial patterning, and meristem maintenance, and responses to abiotic stresses. For example, genes of GAI, RGA, and RGL of the DELLA subfamily were reported as repressors of gibberellin signaling (Stuurman et al. 2002). SCR and SHR could form SCR/SHR complex to participate in root radial patterning and growth, while SCL3 integrates multiple signals mediating root elongation (Cui et al. 2007; Heo et al. 2011). HAM subfamily genes are involved in shoot meristem development (Stuurman et al. 2002). It has been reported that SCL3 can regulate the timing and extent of the middle cortex formation (Heo et al. 2011). DLTs participate in BR signaling in rice (Tong et al. 2009). GRAS1 increases expression levels of reactive oxygen species under various stress conditions (Mayrose et al. 2006). Overexpression of PAT1 enhances abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis (Czikkel and Maxwell 2007). Overexpression of GmGRAS37 improves soybean resistance to drought and salt stresses (Wang et al. 2020). GRAS40 is essential for abiotic stress-induced promoters and auxin and gibberellin signal transduction in tomatoes (Liu et al. 2017).

In addition, GRAS gens have been reported to participate in AM symbiosis. Nodulation signaling pathway 1 (NSP1), NSP2, (Liu et al. 2011), MIG1 (Heck et al. 2016), DELLA (Heck et al. 2016), RAM1 (Required for arbuscular mycorrhiza 1) (Park et al. 2015; Pimprikar et al. 2016) and RAD1 (required for arbuscule development 1) (Xue et al. 2015), have been identified playing key roles in regulating symbiosis between plant and AM fungi. For instance, DELLA is the inhibitor of gibberellic acid (GA) signal, controlling cortical radial cell expansion during arbuscule development (Heck et al. 2016), and RAM1 (Required for arbuscular mycorrhiza 1) regulates arbuscule branching (Park et al. 2015; Pimprikar et al. 2016). GA has been identified as a negative regulator of AM symbiosis, and application of GA can reduce AM colonization and arbuscule abundance, whereas reports have also been shown that insufficient GA signaling can inhibit AM development (El Ghachtouli et al. 1996; Floss et al. 2013; Foo et al. 2013; Nouri et al. 2021; Takeda et al. 2015a; Yu et al. 2014). SCL3 of Arabidopsis, a root-specific GRAS, participates in roots development (Pysh et al. 1999), and acts as a positive regulator for the integration and maintenance of GA pathway function (Heo et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2011). Recently, a study showed that an AM-induced gene (SlGRAS18) from SCARECROW-LIKE3 (SCL3) group plays role in regulating AM development in tomato (Ho-Plágaro et al. 2019). So far, however, little is known about the roles of SCL3 on AM colonized root system, and its functions association with GA.

Lotus japonicus is an important legume pasture crop and also a model species for AM symbiotic research. Whether it contains SCL3 genes that are associated with AM development has not been reported. In this study, all genes of the GRAS family of L. japonicus were identified. Seven GRAS genes belonging to the SCL3 group were identified by phylogenetic analysis. Expression patterns of the seven LjGRAS genes in response to AM colonization and different tissues were examined. The functional characterization of LjGRAS36 in AM symbiosis was further explored. This study provides details of the SCL3 gene and promotes the further functional characterization of them in L. japonicus.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The LORE1a insertion lines LjGRAS36 of Lotus japonicus were obtained from Lotus base (https://lotus.au.dk/) (Mun et al. 2016), and the plant's homozygosity was confirmed by PCR with sequence-specific primers (Forward: TGCGAAAAAGGGAGGAGACGAACA, Reverse: TCCCAAGGCTTGAATTGGCTGGGT). The L. japonicus wild type (WT) Gifu-129 provided by Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangdong, China) was used as a control. L. japonicus were grown in a sterilized vermiculite/perlite mixture (6:1 w/w) under 16 h-light/8-h-dark at 22 °C. Roots were harvested six weeks later. For symbiosis analysis, two weeks old plants were inoculated with Rhizophagus irregularis (Provided by Sun Yat-Sen University), and roots were harvested four weeks later. A half-strength Hoagland solution containing 100 µM NH4H2PO4 was cultured once a week.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from six-week-old AM-colonized and non-colonized roots of Gifu-129 and ljgras36 by using RNAiso Plus Kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China), and purified by using DNase (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China). The purified RNA was then measured by 2100 Bioanalyzer (Aligent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). The library construction, RNA sequencing, and analysis were conducted by LC Sciences (Houston, TX, USA). Library construction was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA). RNAseq was performed on Illumina HiSeq 4000. The reads of Gifu-129 and ljgras36 samples were aligned to the L. japonicus reference 3.0 genome (https://lotus.au.dk/) using the HISAT package (Kim et al. 2015), and maps to the reference genome. Raw transcriptome data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information SRA database with the BioProject accession number PRJNA793601. Genes with log2(fold change) > 1 or log2(fold change) < -1 and with statistical significance (p-value < 0.05) by R package were regarded as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Two biological replications of RNA samples for Gifu-129 and ljgras36 were used for RNA-seq.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA from AM-colonized and non-colonized roots of Gifu-129 and ljgras36 were used for cDNA synthesis by Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA). The qRT-PCR was conducted by using ABI 7300 system. Gene’s relative expression was normalized to the endogenous housekeeping gene Ubiquitin and calculated by 10−(ΔCt /3) (Liao et al. 2015). Primers were designed as reported previously (Xue et al. 2015). Statistical differences analysis between Gifu-129 and ljgras36 were determined by Student’s t-test. Three biological replicates were performed.

Trypan blue staining

Trypan blue staining for mycorrhizal roots of L. japonicus was performed as previously described (Liu et al. 2018). Root segments were fixed in FAA (formalin acetic acid alcohol) for 12 h, and then incubated in 10% KOH for 1 h. After being washed by water, roots were incubated in 2% HCl solution for 5 min. After washing by water, roots were stained in 0.05% trypan blue solution. After staining, roots were rinsed with lactic acid and glycerin solution. AM fungi structures in root fragments were examined by a Leica DM5000B microscope. The root colonization rate was measured as described by Xue et al. (Xue et al. 2015).

Histochemical GUS assays

The pLjGRAS36:GUS was introduced into L. japonicus MG-20 to generate transgenic root through Agrobacterium rhizogenes LBA9402-mediated transformation (Xu et al. 2017). Transgenic L. japonicus hairy roots were harvested at four weeks post-R. irregularis inoculation. X-gluc staining was used to detect GUS activity of R. irregularis inoculated roots.

Mycorrhization and arbuscular size measurement

Mycorrhization and arbuscular size were analyzed according to Xue et al. described (Xue et al. 2015). Mycorrhizal roots structures were classified into four groups: only hyphae (H), hyphae with arbuscules (H + A), hyphae with vesicles (V + H), and hyphae with arbuscular and vesicles (A + V + H). The percentages of each group were calculated by the number of each sector divided by total views under 20× object magnification. Over 200 views per slide were surveyed. For arbuscule size measurement, after trypan blue staining, each arbuscule was measured along the longitudinal direction of the root. Three biological replicas were used.

Bioinformatics analysis

The phylogenic tree of GRAS genes from many species was generated by the neighbor-joining method based on amino acid sequences (bootstrap values = 1000 replicates) in MEGA6 (Tamura et al. 2013). Molecular modeling of protein was predicted by the I-TASSER server (Yang et al. 2013). RSAT was used to analyze the promoter cis-acting element (Medina-Rivera et al. 2015).

Results

Identification of SCL3 genes in Lotus japonicus

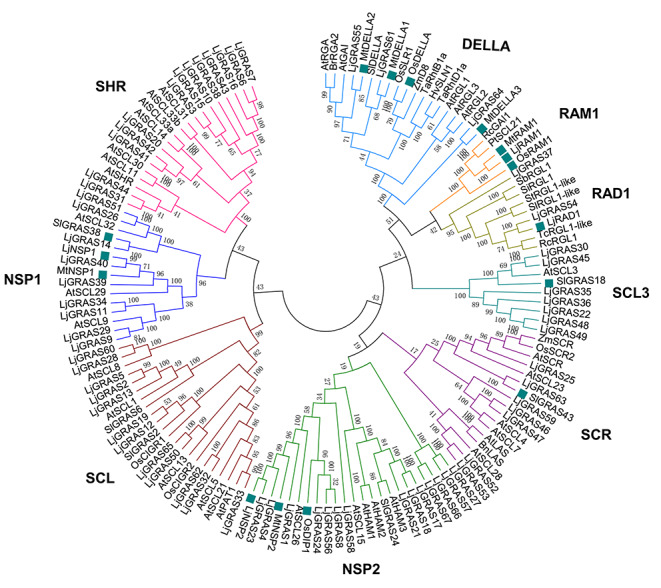

To identify GRAS proteins in the Lotus japonicus, GRAS proteins MtDELLA1, MtNSP1, MtNSP2, and MtRAM1 were used as queries for BLAST. In total, 67 putative LjGRAS genes were identified from L. japonicus (Table S1). To better characterize the evolutionary relationships of these LjGRAS members, a phylogenetic tree containing functional known GRASs was generated (Fig. 1). The 67 GRASs were divided into nine groups, DELLA group, RAM1 group, RAD1 group, SCL3 group, SCR group, NSP2 group, SCL group, NSP1 group, and SHR group. Among them, group NSP1, NSP2, DELLA, RAD1, RAM1, SCL3, and SCR contained symbiosis-associated GRAS members. Together with MtNSP1 from Medicago truncatula, LjNSP1 from L. japonicus, and SlGRAS38 from tomato, nine LjGRAS members consisted of the NSP1 group; 14 LjGRAS members together with MtNSP2 from M. truncatula, LjNSP2 from L. japonicus, and OsDIP1 from rice were classified into the NSP2 group; whereas DELLA group and RAM1, included three and two LjGRAS members, respectively. In addition, the group SCL3 and SCR were each composed of seven LjGRAS members and clustered with SlGRAS18 and SlGRAS43 from tomato respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of LjGRAS members. Symbiosis-related GRASs were indicated by solid green blocks. GRAS proteins from Arabidopsis (At), maize (Zm), rice (Os), Medicago truncatula (Mt), Lotus japonicus (Lj), Brassica napus (Bn), Brassica rapa (Br), Populus trichocarpa (Pt), Ricinus communis (Rc), Sorghum bicolor (Sb), Setaria italica (Si), Solanum lycopersicum (Sl), Hordeum vulgare (Hv), Triticum aestivum (Ta), Solanum tuberosum (St) and Theobroma cacao (Tc). The phylogenetic tree was generated by MEGA6. Neighbor-Joining model (bootstrap = 1000) was used

Tissue expression patterns and responses of SCL3 genes to AM colonization

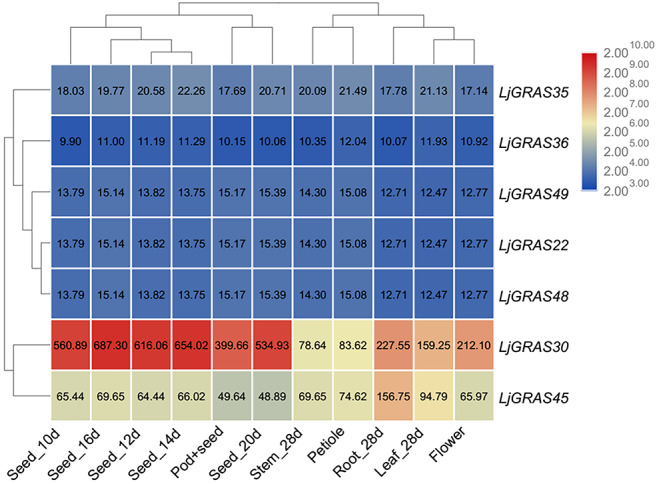

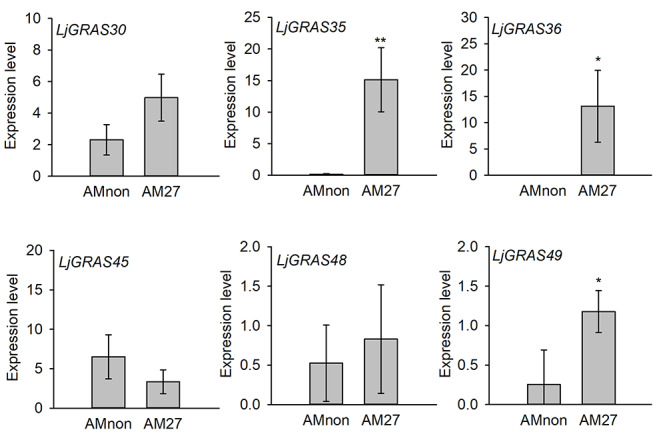

GRAS genes belonging to the SCL group were reported to be involved in AM symbiosis. In this study, expression patterns of the seven SCL3 genes in root, stem, leaf, petiole, flowers, pods, and seeds of L. japonicus were analyzed based on transcriptome data from Verdier et al. (Verdier et al. 2013). LjGRAS30 and LjGRAS45 exhibited high expression levels in all detected tissues, while the other five SCL3 genes expressed lower in all tissues. In particular, the expression level of LjGRAS36 was undetectable in all tested tissues (Fig. 2). Expression levels of LjGRAS genes belonging to the SCL3 group in arbuscular mycorrhiza colonized roots were further analyzed based on transcriptome data from Handa et al. (Handa et al. 2015). No expression of LjGRAS22 was detected either in AM colonized root or non-AM colonized root. Upon AM fungal inoculation, the expression levels of three SCL3 genes, including LjGRAS35, LjGRAS36, and LjGRAS49, in colonized roots were substantially upregulated at 27-day post-AM colonization (Fig. 3). Moreover, the expression levels of LjGRAS35, LjGRAS36, and LjGRAS49 under different treatments and in different genotypes were analyzed based on data from the lotus base. As figure S1 showed, LjGRAS36 expressed especially high just in colonized roots compared with all the other detected experiments (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Heat map representation and hierarchical clustering of SCL3 members in different tissues. Data were obtained from Lotus base (https://lotus.au.dk/). The value bar was shown on the right, and red to blue colors represent high to low expression levels

Fig. 3.

Expression patterns of SCL3 members in response to AM symbiosis. Data were obtained from Lotus base (https://lotus.au.dk/). Amnon represents roots not inoculated with AM fungi and AM27 represents roots inoculated with AM fungi for 27 days. Error bars represent SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between non-colonized and colonized roots (Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01)

Characterization of LjGRAS36 in Lotus japonicus

Given the specific and most responses to AM colonization in roots of L. japonicus, LjGRAS36 was selected for further analysis. The full-length coding DNA sequence of LjGRAS36 is 1302 bp, and its predicted protein size is 48.9 kD. LjGRAS36 is closely clustered with the Arabidopsis GRAS member AtSCL3 (Fig. 1), and the amino acid sequences of LjGRAS36 and AtSCL3 shared four conserved domains with high levels of similarity, including leucine heptad repeat I (LHR I), VHIID, LHR II and SAW domains (Fig. S2A). Further predicted 3D (dimensional) structure model of LjGRAS36 based on template 6kpb.1.A consisted of seven β-sheet and twelve α-helix similar with that of AtSCL3 and SlGRAS18 (Fig. S2B). The predicted ligand binding site of LjGRAS36 contains the key amino acid residues including K166, L195, Q196, F197, Q227, L228, H229, S230, N250, Q251, S252, K255.

The LjGRAS36 promoter drives GUS expression strongly in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonizing roots

Promoter cis-element analysis revealed that the LjGRAS36 promoter contained two conserved motifs, CTTC motif (TCTT/CCGT) and GCCGGC motif (GCCGGC) (Fig. 4 A), which were associated with AM symbiosis (Favre et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2016, 2018; Lota et al. 2013; Pimprikar et al. 2016; Xue et al. 2018). To explore the expression of LjGRAS36 in response to AM symbiosis, a 1,000 bp predicted promoter sequence of LjGRAS36 fused with the GUS reporter gene was introduced into L. japonicus roots. The hairy root lines expressing the GUS reporter driven by the LjGRAS36 promoter were generated. The roots were further inoculated with AM fungi (Rhizophagus irregularis), and GUS activity was measured. GUS staining could not be observed in non-colonized transgenic plant roots (Fig. 4B) but was detectable in the root of the AM fungi colonized roots (Fig. 4 C).

Fig. 4.

Histochemical staining for the promoter activity of LjGRAS36 using the GUS reporter gene. (A) AM-responsive elements analysis of LjGRAS36 promoter by RSAT. (B) GUS activity was not detected in the roots of pLjGRAS36:GUS transgenic plants in absence of R. irregularis. Bar = 200 μm. (C) GUS activity was detected in the roots of pLjGRAS36:GUS transgenic plants in presence of R. irregularis. Bar = 200 μm

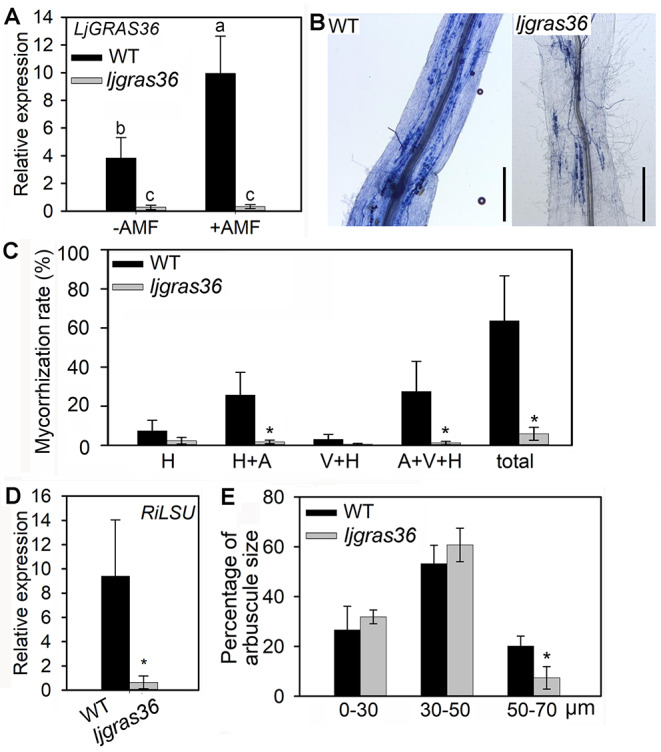

LjGRAS36 plays important roles in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi symbiosis

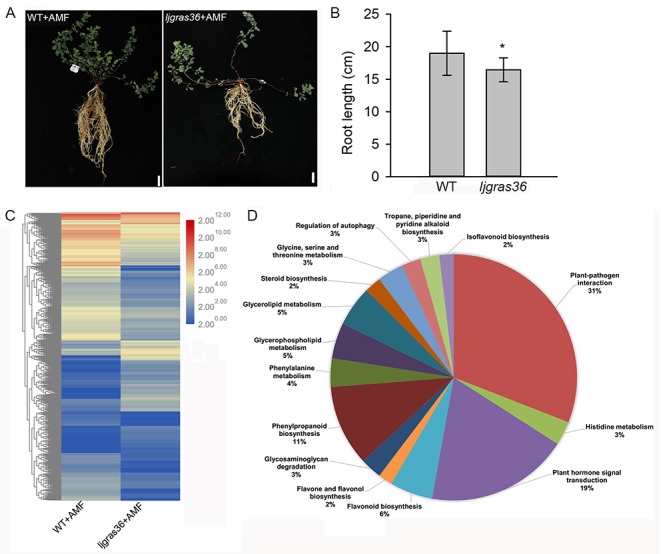

The relative expression of LjGRAS36 in AM fungi (R. irregularis) colonized or non-colonized roots of wild type (Gifu-129) further indicated LjGRAS36 is AM inducible (Fig. 5 A). To further confirm the function of LjGRAS36 in AM colonization, a ljgras36 mutant was identified. The L. japonicus mutant ljgras36 contains a LORE1a insertion in the SAW domain of LjGRAS36 was used (Fig. S3A). Homozygosity of ljgras36 plants was confirmed by PCR (Fig. S3B). Compared with wild type, no matter in R. irregularis colonized or non-colonized roots, the transcript level of LjGRAS36 was reduced in ljgras36 (Fig. 5 A). The R. irregularis colonized ljgras36 can form normal arbuscular, vesicle, and hyphae (Fig. 5B), but the total mycorrhization rates in ljgras36 were significantly decreased when compared with wild type. A significantly reduced degree of arbuscules, vesicles, and hyphae was observed in ljgras36 (Fig. 5 C). Transcripts of RiLSU (the large subunit of R. irregularis) can confirm the presence of the AM fungus in all samples (Xue et al. 2015). The expression of RiLSU was significantly reduced (> 14-fold change) in the roots of R. irregularis colonized ljgras36 compared with R. irregularis colonized wild type (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the arbuscular number and size were significantly reduced in ljgras36 plants. Analysis of the arbuscular sizes revealed that the proportion of arbuscules size ranged from 0 to 50 μm in ljgras36 plants, which was not significantly different from that of the wild type (Fig. 5E), whereas, the percentage of arbuscules size ranging from 50 to 70 μm was reduced significantly in ljgras36 plants compared with the wild type (Fig. 5E). In addition, ljgras36 conferred a shorter root phenotype than wild type in the presence of R. irregularis (Fig. 6 A & B).

Fig. 5.

Mycorrhizal phenotype in ljgras36 mutant. (A) Expression levels of LjGRAS36 in R. irregularis colonized (+ AMF) and non-colonized (-AMF) roots of wild type (WT) and ljgras36. Three biological replicates were used. Error bars represent SD. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences at the P < 0.05 level. (B) Micrograph of mycorrhizal ljgras36 mutant and WT. Bar = 500 μm. (C) Mycorrhization rate of R. irregularis colonized roots of ljgras36 and WT at four weeks post-inoculation. Error bars represent SD. Three biological replicates with approximately 90 root segments per genotype were set. Asterisks indicate significant differences between WT and ljgras36 (Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05). (D) Expression levels of RiLSU in R. irregularis colonized roots of wild type (WT) and ljgras36. RiLSU indicates R. irregularis large subunit. Three biological replicates were used. Error bars represent SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between WT and ljgras36 mutant (Student’s t test, *P < 0.05). (E) Arbuscular size classes in the WT and ljgras36 mutant plants. Three biological replicates with approximately 400 arbuscules were measured per genotype. Error bars represent SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between WT and ljgras36 mutant (Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05)

Fig. 6.

LjGRAS36 influences on the root of Lotus japonicus post-AMF colonization. (A) Phenotypes of wild type L. japonicus and ljgras36 mutant post AM colonization. Bar = 2 cm. (B) Root length of WT and ljgras36 mutant post-AM colonization (Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05). Seventeen plants were measured for each phenotype. (C) Hierarchical cluster analysis of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs, log2(fold change) > 1 or log2(fold change) < -1, p < 0.05) between roots of wild type (WT) and ljgras36 post AM fungi colonization. +AMF means roots colonized by AM fungi. (D) Pie chart presentation of KEGG pathway analysis between WT and ljgras36

ljgras36 influences GA-related genes expression

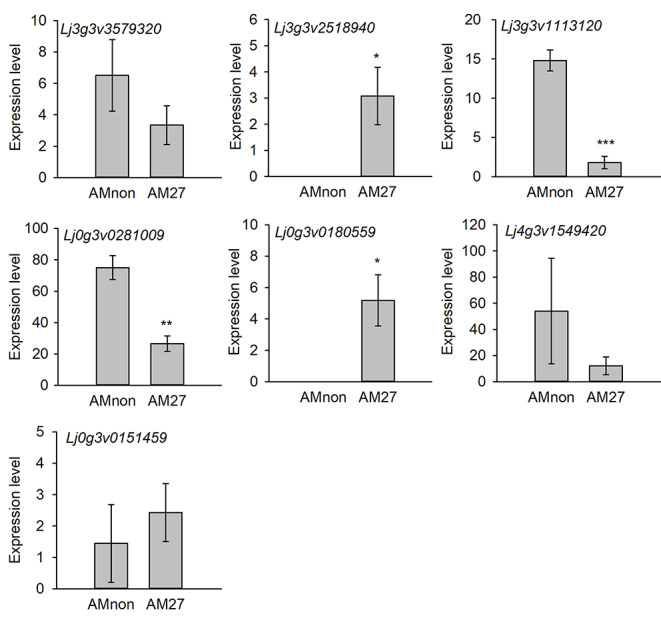

Given that a TF is unlikely to act independently in plants, we reasoned that the ljgras36 mutant could interfere with the expression of some LjGRAS36-related genes. The functions of these LjGRAS36-related genes may be essential in regulating symbiosis. To find genes that depend on the expression of LjGRAS36 post AM fungal inoculation, the transcriptome analysis of AM fungi colonized roots was performed. In total, 1280 differentially expressed genes (DEGs, p-value < 0.05) containing 464 up-regulated genes and 816 down-regulated genes were identified (Fig. 6 C, Table S2). KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analysis revealed ljgras36 mutant influences many genes (19%) involved in plant hormone signal transduction (Fig. 6D). Further, a significant enrichment in GA-related genes (Lj0g3v0151459, Lj0g3v0180559, Lj4g3v1152920, Lj3g3v1113120, Lj3g3v2518940, Lj3g3v3056660, Lj3g3v3056670, Lj3g3v3579320, Lj4g3v1549420, Lj0g3v0281009, Lj0g3v0357169) were found by Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. The eleven GA-related genes were involved in GA biosynthetic process, response to GA, cellular response to GA stimulus, and regulation of the GA biosynthetic process (Table 1). Expression levels of the eleven GA-related genes in AM fungi colonized roots were further analyzed based on transcriptome data from Handa et al. (Handa et al. 2015). Upon AM fungal inoculation, the expression levels of Lj0g3v0180559 involved in the GA biosynthetic process, and Lj3g3v2518940 involved in response to GA process was substantially upregulated in colonized roots at 27-day post AM fungi colonization, whereas Lj3g3v1113120 was involved in response to GA process, and Lj0g3v0281009 was involved in the cellular response to GA stimulus were significantly downregulated in colonized roots (Fig. 7).

Table 1.

GA-related different expression genes examined by Gene Ontology (GO) database

| GO ID | GO Term | Genes | Description | log2 (fc) | pval | qval | regulation | significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0009686 | gibberellin biosynthetic process | Lj0g3v0151459 | PREDICTED: ent-kaurene oxidase, chloroplastic [Glycine max] | -1.77 | 0.03 | 0.78 | down | yes |

| Lj0g3v0180559 | PREDICTED: ent-kaurene oxidase, chloroplastic [Glycine max] | -1.86 | 0.02 | 0.51 | down | yes | ||

| Lj4g3v1152920 | Ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase 2 [Glycine soja] | -2.87 | 0.03 | 0.68 | down | yes | ||

| GO:0009739 | response to gibberellin | Lj3g3v1113120 | unknown | 3.62 | 0 | 0.13 | up | yes |

| Lj3g3v2518940 | PREDICTED: late elongated hypocotyl and circadian clock associated-1-like protein 1 isoform X1 [Glycine max] | -2.04 | 0 | 0.11 | down | yes | ||

| Lj3g3v3056660 | unknown | 3.67 | 0 | 0.12 | up | yes | ||

| Lj3g3v3056670 | unknown | 3.67 | 0 | 0.12 | up | yes | ||

| Lj3g3v3579320 | PREDICTED: scarecrow-like protein 3 isoform X1 [Glycine max] | inf | 0 | 0 | up | yes | ||

| Lj4g3v1549420 | unknown | -2.15 | 0.01 | 0.46 | down | yes | ||

| GO:0071370 | cellular response to gibberellin stimulus | Lj0g3v0281009 | soluble acid invertase FRUCT2 [Medicago truncatula] | 2.51 | 0 | 0.03 | up | yes |

| GO:0010371 | regulation of gibberellin biosynthetic process | Lj0g3v0357169 | PREDICTED: dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 1E [Glycine max] | -3.08 | 0.01 | 0.39 | down | yes |

Fig. 7.

Expression patterns of DEGs related to GA signal transduction pathway in wild type post AM colonization. The expression date was collected from Lotus Base (https://lotus.au.dk/). AMnon represents roots that were not inoculated with AM fungi, and AM27 represents roots that were inoculated with AM fungi for 27 days

Discussion

Members of the GRAS family have been identified in several plants (Huang et al. 2015; Liu and Widmer 2014; Lu et al. 2015; Song et al. 2014; Tian et al. 2004), and their critical roles in regulating mycorrhizal formation have been elucidated. In the present study, a total of 67 LjGRAS members were identified from L. japonicus. In phylogenetic analysis, 42 of 67 LjGRAS members were clustered into groups containing symbiosis-related GRAS proteins, including NSP1, NSP2, DELLA, RAD1, RAM1, SCL3, and SCR (Fig. 1). A new GRAS gene of tomato belonging to SCL3 group playing roles in mycorrhizal development has been reported recently (Ho-Plágaro et al. 2019). However, whether SCL3 genes play a similar role in different species is still unknown. L. japonicus is a model species used for the investigation of plant-AM fungi symbiosis. But SCL3 genes in L. japonicus and their response to AM colonization remain unknown. With the release of a more comprehensive L. japonicus genome database (v3.0), it is possible to characterize SCL3 members and explore their functions in AM symbiosis.

In the SCL3 group of this study, AtSCL3 functions in non-host Arabidopsis, whereas SlGRAS18 plays a symbiotic role in tomato (Ho-Plágaro et al. 2019), suggesting these seven SCL3 members in L. japonicus may not all participate in arbuscular mycorrhizal development. The RNA-seq profiles of arbuscular mycorrhiza colonized L. japonicus roots showed only three of the seven LjSCL3 genes were significantly induced in mycorrhization (Fig. 3), further indicating that not all SCL3 genes were involved in arbuscular mycorrhiza development. Among the three LjSCL3 genes, expression patterns and promoter analysis of LjGRAS36 suggested the potential roles of LjGRAS36 in AM symbiosis.

The motifs that are conducive to the function of proteins in GRAS, containing LHR I, LHR II, VHIID and SAW are conserved. The LHRI domain is necessary and sufficient for the GRAS-protein interaction during nodulation signaling in Medicago truncatula (Hirsch et al. 2009). Although the LHR II domain does not appear to play a key role in protein-protein interactions, it has been reported that two direct GRAS-protein associations require either only the LHR II domain or the central part containing LHR I and LHR II (Bartoli et al. 2013; Hirsch et al. 2009). Protein-protein interactions have been observed between the GRAS proteins, which is indispensable for their action. In M. truncatula the formation of NSP1/NSP2 is necessary for efficient nodule development. Mutation in the SAW motif showed distinct phenotypic abnormalities in Arabidopsis (Itoh et al. 2002). The LORE1 in ljgras36 mutant used in this study was inserted in the SAW motif. Changes of SAW motif in LjGRAS36 in ljgras36 mutant also resulted in phenotypic changes in L. japonicas, further indicating that the SAW domain is important for the functions of GRAS genes.

The AM fungi colonized roots of ljgras36 revealed a reduced mycorrhizal rate, especially in arbuscular formation (Fig. 5 C), indicating the requirement of functional LjGRAS36 in arbuscular mycorrhiza development. In addition, AM fungi colonized roots of ljgras36 showed a similar frequency of hyphae with that of wild type, but lower rates of arbuscular and vesicles formation in roots (Fig. 5 C), indicating that LjGRAS36 may participate in the formation of arbuscular. Moreover, the percentage of arbuscules size ranging from 50 to 70 μm was significantly reduced in AM fungi colonized roots of ljgras36 (Fig. 5E). This pattern of impaired arbuscule formation was also described for another GRAS gene RAD1 (Xue et al. 2015). The rad1 mutant showed a significantly reduced percentage of sectors with arbuscular, vesicles, and hyphae, and much less of arbuscules ranging from 50 to 70 μm (Xue et al. 2015). Studies have revealed that DELLA proteins positively regulate expressions of symbiosis-related RAM1 and RAD1 (Floss et al. 2017; Park et al. 2015; Pimprikar et al. 2016). Transcriptome data showed that RAD1 ortholog LjGRAS54 and DELLA ortholog LjGRAS64 have a downward tendency in AM fungi colonized roots of ljgras36. The down-regulation of LjGRAS64 in AM fungi colonized roots of ljgras36 may result in decreased expression of LjGRAS54, which would lead to the reduced arbuscular size. In addition, a gene encoding phosphate transporter, Lj6g3v0030050, was significantly reduced in AM fungi colonized roots of ljgras36 (Table S2), indicating the functional defect of LjGRAS36 results in the decrease of phosphate (Pi) transporters expression, which will lead to reduced Pi transport and uptake. The decreased import of Pi nutrient to plant host would reduce carbon export from host to AM fungi, resulting in disrupt arbuscular development (Wang et al. 2017).

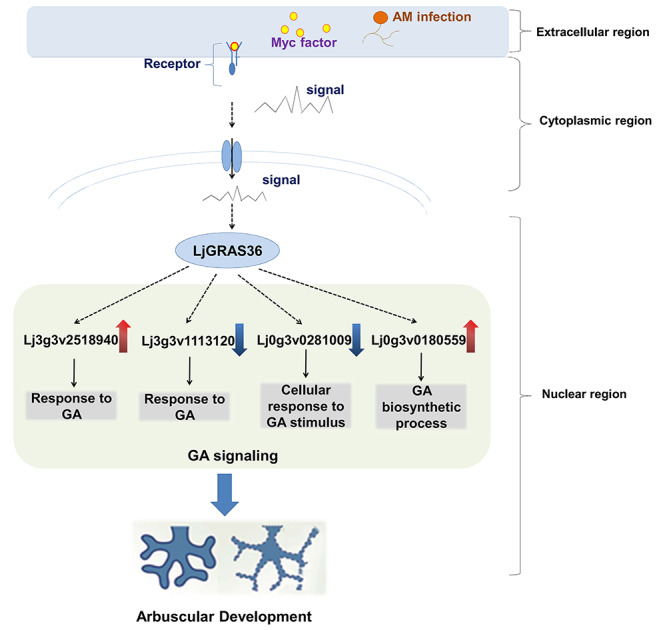

Since the role of SCL3 is related to GA, we focused on differentially expressed GA-related genes between AM fungi colonized roots of ljgras36 and wild type examined by the GO database (Table 1). Especially, among them, four different expressed GA-related genes were also regulated by AM symbiosis. It is known that the GA pathway plays an important role during mycorrhization. The genes Lj3g3v2518940 and Lj0g3v0180559 were upregulated during mycorrhization and downregulated in mycorrhizal ljgras36 plants, which with less mycorrhization. Conversely, Lj3g3v1113120 and Lj0g3v0281009 were downregulated during mycorrhization in WT, while upregulated in mutant plants, indicating mycorrhization inhibits their expression. Therefore, the differential expressions of these GA-related genes might result from the changed rate of mycorrhization in ljgras36 plants. In addition, given that LjGRAS36 shared high sequence similarity to AtSCL3 (Fig. 1 & Fig. S2), which is repressed by GA in Arabidopsis (Zhang et al. 2011), LjGRAS36 may also be involved in GA signal transduction like AtSCL3. The study has been revealed that the GA/DELLA module plays an important role during AM formation (Takeda et al. 2015b). SCL3 antagonistically interacts with DELLA playing opposite roles in regulating downstream GA responses (Zhang et al. 2011). Additionally, DELLA induces the transcription of SCL3 (Zentella et al. 2007). Above all, LjGRAS36 might be a component of GA/DELLA/SCL3 to control arbuscular mycorrhiza formation through the GA signal transduction pathway. Based on these results, we proposed a hypothetical model to describe how LjGRAS36 influences arbuscular development. The hypothesized model is that when the AM symbiotic signal pathway is activated, LjGRAS36 is activated by this symbiotic signal, and then regulated arbuscular development by regulating genes involved in GA biosynthetic or response processes (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Hypothesized model of the mechanism that LjGRAS36 regulates arbuscular development

In the conclusion, a SCARECROW-LIKE3 gene, LjGRAS36, was identified from L. japonicus in the present study. LjGRAS36 was induced by AM colonization. The LjGRAS36 functional loss mutant ljgras36 of L. japonicus exhibited a significantly reduced mycorrhizal colonization rate and arbuscular size. Transcriptome analysis revealed LjGRAS36 may regulate AM development in L. japonicus through GA signal pathways. In the future, LjGRAS36 can act as a candidate gene to influence AM symbiosis formation with genetic engineering techniques.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Figure S1 Heat map representation of three AM-induced GRAS genes belonging to the SCL3 group under different treatment. Data was obtained from Lotus base (https://lotus.au.dk/). The value bar is shown on the right, and red to blue colors represent high to low expression levels.

Figure S3 Gene structure of LjGRAS36 in wild type Lotus japonicus and ljgras36 mutant. (A) Gene structure of LjGRAS36 and position of the LORE1a insertion in ljgras36. Gray arrows indicate the LORE1a transposon. (B) Identification of homozygous ljgras36 through genomic DNA amplification. M represents DNA marker. Gifu represents wild type L. japonicus

Figure S2 Conserved amino acids sequence and protein structure of LjGRAS36. (A) Sequence alignment of LjGRAS36, AtSCL3, and SlGRAS18. The identical deduced amino acids were shaded by the red box. Highly conserved regions were indicated by black lines with motif names. (B) The predicted 3D structures of LjGRAS36, AtSCL3, and SlGRAS18 based on template 6kpb.1.A

Authors’ contributions

YX, FL, and XL conceived the project. YX, FW, RZ, and FL carried out the experiments. FL and YX performed the bioinformatics analysis. FL and YX wrote the manuscript. XL and JW reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31902104).

Declarations

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jianping Wu, Email: jianping.wu@ynu.edu.cn.

Xiaoyu Li, Email: lixiaoyu@ahau.edu.cn.

References

- Bartoli B, Bernardini P, Bi XJ, Bolognino I, Branchini P, Budano A, Melcarne AKC, Camarri P, Cao Z, Cardarelli R, Catalanotti S, Cattaneo C, Chen SZ, Chen TL, Chen Y, Creti P, Cui SW, Dai BZ, Staiti GD, D’Amone A, De Danzengluobu I, Piazzoli BD, Di Girolamo T, Ding XH, Di Sciascio G, Feng CF, Feng ZY, Feng ZY, Galeazzi F, Giroletti E, Gou QB, Guo YQ, He HH, Hu HB, Hu HB, Huang Q, Iacovacci M, Iuppa R, James I, Jia HY, Labaciren, Li HJ, Li JY, Li XX, Liguori G, Liu C, Liu CQ, Liu J, Liu MY, Lu H, Ma LL, Ma XH, Mancarella G, Mari SM, Marsella G, Martello D, Mastroianni S, Montini P, Ning CC, Pagliaro A, Panareo M, Panico B, Perrone L, Pistilli P, Ruggieri F, Salvini P, Santonico R, Sbano SN, Shen PR, Sheng XD, Shi F, Surdo A, Tan YH, Vallania P, Vernetto S, Vigorito C, Wang B, Wang H, Wu CY, Wu HR, Xu B, Xue L, Yang QY, Yang XC, Yao ZG, Yuan AF, Zha M, Zhang HM, Zhang JL, Zhang JL, Zhang L, Zhang P, Zhang XY, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhaxiciren XX, Zhu FR, Zhu QQ, Zizzi G, Collaboration (2013) A-Y Observation of TeV gamma rays from the unidentified source HESS J1841-055 with the ARGO-YBJ Experiment. Astrophys J767: 99

- Bolle C. The role of GRAS proteins in plant signal transduction and development. Planta. 2004;218:683–692. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1203-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci A, Rouard M. Evolutionary analyses of GRAS transcription fctors in Angiosperms. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:273. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Jin W, Liu A, Zhang S, Liu D, Wang F, Lin X, He C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) increase growth and secondary metabolism in cucumber subjected to low temperature stress. Sci Hort. 2013;160:222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Lee T, Cho J, Servante EK, Pucker B, Summers W, Bowden S, Rahimi M, An K, An G, Bouwmeester HJ, Wallington EJ, Oldroyd G, Paszkowski U. The negative regulator SMAX1 controls mycorrhizal symbiosis and strigolactone biosynthesis in rice. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16021-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Levesque MP, Vernoux T, Jung JW, Paquette AJ, Gallagher KL, Wang JY, Blilou I, Scheres B, Benfey PN. An evolutionarily conserved mechanism delimiting SHR movement defines a single layer of endodermis in plants. Science. 2007;316:421–425. doi: 10.1126/science.1139531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czikkel BE, Maxwell DP. NtGRAS1, a novel stress-induced member of the GRAS family in tobacco, localizes to the nucleus. J Plant Physiol. 2007;164:1220–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghachtouli N, Martin-Tanguy J, Paynot M, Gianinazzi S. First report of the inhibition of arbuscular mycorrhizal infection of Pisum sativum by specific and irreversible inhibition of polyamine biosynthesis or by gibberellic acid treatment. FEBS Lett. 1996;385:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre P, Bapaume L, Bossolini E, Delorenzi M, Falquet L, Reinhardt D (2014) A novel bioinformatics pipeline to discover genes related to arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis based on their evolutionary conservation pattern among higher plants. BMC Plant Biol14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fiorilli V, Vannini C, Ortolani F, Garcia-Seco D, Chiapello M, Novero M, Domingo G, Terzi V, Morcia C, Bagnaresi P, Moulin L, Bracale M, Bonfante P. Omics approaches revealed how arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis enhances yield and resistance to leaf pathogen in wheat. Sci Rep-UK. 2018;8:9625. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floss DS, Levy JG, Lévesque-Tremblay V, Pumplin N, Harrison MJ. DELLA proteins regulate arbuscule formation in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E5025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308973110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floss DS, Gomez SK, Park HJ, Maclean AM, Müller LM, Bhattarai KK, Lévesque-Tremblay V, Maldonado-Mendoza IE, Harrison MJ. A transcriptional program for arbuscule degeneration during AM symbiosis is regulated by MYB1. Curr Biol. 2017;27:1206–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo E, Ross JJ, Jones WT, Reid JB. Plant hormones in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses: an emerging role for gibberellins. Ann Bot-London. 2013;111:769–779. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavito ME, Olsson PA, Rouhier H, Medina-Penafiel A, Jakobsen I, Bago A, Azcon-Aguilar C. Temperature constraints on the growth and functioning of root organ cultures with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New phytol. 2005;168:179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman SI, Casper BB. Biotic contexts alter metal sequestration and AMF effects on plant growth in soils polluted with heavy metals. Ecology. 2012;93:1550–1559. doi: 10.1890/10-2135.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr C, Banba M, Croset V, An K, Miyao A, An G, Hirochika H, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Paszkowski U. Arbuscular mycorrhiza-specific signaling in rice transcends the common symbiosis signaling pathway. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2989–3005. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa Y, Nishide H, Takeda N, Suzuki Y, Kawaguchi M, Saito K. RNA-seq transcriptional profiling of an arbuscular mycorrhiza provides insights into regulated and coordinated gene expression in Lotus japonicus and Rhizophagus irregularis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:1490–1511. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrier LA, Watson CA. The potential role of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi in the bioprotection of plants against soil-borne pathogens in organic and/or other sustainable farming systems. Pest Manag Sci. 2004;60:149–157. doi: 10.1002/ps.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MJ. Signaling in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Annu Rev of Microbiol. 2005;59:19–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck C, Kuhn H, Heidt S, Walter S, Rieger N, Requena N. Symbiotic fungi control plant root cortex development through the novel GRAS transcription factor MIG1. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2770–2778. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo JO, Chang KS, Kim IA, Lee MH, Lee SA, Song SK, Lee MM, Lim J. Funneling of gibberellin signaling by the GRAS transcription regulator scarecrow-like 3 in the Arabidopsis root. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2166–2171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012215108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch S, Kim J, Munoz A, Heckmann AB, Downie JA, Oldroyd GED. GRAS proteins form a DNA binding complex to induce gene expression during nodulation signaling in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell. 2009;21:545–557. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho-Plágaro T, Molinero-Rosales N, Fariña Flores D, Villena Díaz M, García-Garrido JM. Identification and expression analysis of GRAS transcription factor genes involved in the control of arbuscular mycorrhizal development in tomato. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:268. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Xian ZQ, Kang X, Tang N, Li ZG. Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of GRAS gene family in tomato. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:209. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0590-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Ueguchitanaka M, Sato Y, Ashikari M, Matsuoka M. The gibberellin signaling pathway is regulated by the appearance and disappearance of SLENDER RICE1 in Nuclei. Plant Cell. 2002;14:57–70. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir I, Fontaine J, Lounes-Hadj Sahraoui A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal responses to abiotic stresses: A review. Phytochemistry. 2016;123:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao DH, Chen X, Chen AQ, Wang HM, Liu JJ, Liu JL, Gu M, Sun SB, Xu GH. The characterization of six auxin-induced tomato GH3 Genes uncovers a member, SlGH3.4, strongly responsive to arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:674–687. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Kohlen W, Lillo A, Op den Camp R, Ivanov S, Hartog M, Limpens E, Jamil M, Smaczniak C, Kaufmann K, Yang W-C, Hooiveld GJEJ, Charnikhova T, Bouwmeester HJ, Bisseling T, Geurts R. Strigolactone biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula and rice requires the symbiotic GRAS-type transcription factors NSP1 and NSP2. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3853. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.089771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XY, Widmer A. Genome-wide comparative analysis of the GRAS gene family in populus, Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2014;32:1129–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Xu Y, Jiang H, Jiang C, Du Y, Cheng G, Wang W, Zhu S, Han G, Cheng B. Systematic identification, evolution and expression analysis of the Zea mays PHT1 gene family reveals several new members involved in root colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:930. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Huang W, Xian Z, Hu N, Lin D, Ren H, Chen J, Su D, Li Z. Overexpression of SlGRAS40 in tomato enhances tolerance to abiotic stresses and influences auxin and gibberellin sgnaling. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1659. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Xu Y, Han G, Wang W, Li X, Cheng B. Identification and functional characterization of a maize phosphate transporter induced by mycorrhiza formation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:1683–1694. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lota F, Wegmüller S, Buer B, Sato S, Bräutigam A, Hanf B, Bucher M. The cis-acting CTTC-P1BS module is indicative for gene function of LjVTI12, a Qb-SNARE protein gene that is required for arbuscule formation in Lotus japonicus. Plant J. 2013;74:280–293. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JX, Wang T, Xu ZD, Sun LD, Zhang QX. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in Prunus mume. Mol Genet Genomics. 2015;290:303–317. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0918-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrose M, Ekengren SK, Melech-Bonfil S, Martin GB, Sessa G. A novel link between tomato GRAS genes, plant disease resistance and mechanical stress response. Mol Plant Pathol. 2006;7:593–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Rivera A, Defrance M, Sand O, Herrmann C, Castro-Mondragon JA, Delerce J, Jaeger S, Blanchet C, Vincens P, Caron C, Staines DM, Contreras-Moreira B, Artufel M, Charbonnier-Khamvongsa L, Hernandez C, Thieffry D, Thomas-Chollier M, van Helden J. RSAT 2015: Regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W50–W56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun T, Bachmann A, Gupta V, Stougaard J, Andersen SU. LotusBase: An integrated information portal for the model legume Lotus japonicus. Sci Rep-UK. 2016;6:39447. doi: 10.1038/srep39447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri E, Surve R, Bapaume L, Stumpe M, Chen M, Zhang Y, Ruyter-Spira C, Bouwmeester H, Glauser G, Bruisson S, Reinhardt D. Phosphate suppression of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis involves gibberellic acid signaling. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021;62:959–970. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcab063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HJ, Floss DS, Levesque-Tremblay V, Bravo A, Harrison MJ. Hyphal branching during arbuscule development requires reduced arbuscular mycorrhiza1. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:2774–2788. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimprikar P, Carbonnel S, Paries M, Katzer K, Klingl V, Bohmer Monica J, Karl L, Floss Daniela S, Harrison Maria J, Parniske M, Gutjahr C. A CCaMK-CYCLOPS-DELLA complex activates transcription of RAM1 to regulate arbuscule branching. Curr Biol. 2016;26:987–998. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pysh L, Wysockadiller J, Camilleri C, Bouchez D, Benfey PN. The GRAS gene family in Arabidopsis: sequence characterization and basic expression analysis of the SCARECROW-LIKE genes. Plant J. 1999;18:111–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Lozano JM, Aroca R, Zamarreño ÁM, Molina S, Andreo‐Jiménez B, Porcel R, García‐Mina JM, Ruyter‐Spira C, López‐Ráez JAJP, Cell E. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis induces strigolactone biosynthesis under drought and improves drought tolerance in lettuce and tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:441–452. doi: 10.1111/pce.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Lozano JM, Porcel R, Calvo-Polanco M, Aroca R. Improvement of salt tolerance in rice plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal Symbiosis. In: Giri B, Prasad R, Varma A, editors. Root Biology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Song XM, Liu TK, Duan WK, Ma QH, Ren J, Wang Z, Li Y, Hou XL. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp pekinensis) Genomics. 2014;103:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Chen D, Lu K, Sun Z, Zeng R. Enhanced tomato disease resistance primed by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:786. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuurman J, Jaggi F, Kuhlemeier C. Shoot meristem maintenance is controlled by a GRAS-gene mediated signal from differentiating cells. Gene Dev. 2002;16:2213–2218. doi: 10.1101/gad.230702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Xue B, Jones WT, Rikkerink E, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. A functionally required unfoldome from the plant kingdom: intrinsically disordered N-terminal domains of GRAS proteins are involved in molecular recognition during plant development. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;77:205–223. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9803-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Handa Y, Tsuzuki S, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kawaguchi M. Gibberellin regulates infection and colonization of host roots by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Signal Behav. 2015;10:e1028706. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1028706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Handa Y, Tsuzuki S, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kawaguchi M. Gibberellins interfere with symbiosis signaling and gene expression and alter colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in Lotus japonicus. Plant physiol. 2015;167:545–557. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.247700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian CG, Wan P, Sun SH, Li JY, Chen MS. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;54:519–532. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000038256.89809.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H, Jin Y, Liu W, Li F, Fang J, Yin Y, Qian Q, Zhu L, Chu C. DWARF AND LOW-TILLERING, a new member of the GRAS family, plays positive roles in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Plant J. 2009;58:803–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier J, Torres-Jerez I, Wang M, Andriankaja A, Allen SN, He J, Tang Y, Murray JD, Udvardi MK. Establishment of the Lotus japonicus gene expression atlas (LjGEA) and its use to explore legume seed maturation. Plant J. 2013;74:351–362. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos C, Schouteden N, van Tuinen D, Chatagnier O, Elsen A, De Waele D, Panis B, Gianinazzi-Pearson V. Mycorrhiza-induced resistance against the root–knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita involves priming of defense gene responses in tomato. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;60:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Shi J, Xie Q, Jiang Y, Yu N, Wang E. Nutrient exchange and regulation in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mol plant. 2017;10:1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TT, Yu TF, Fu JD, Su HG, Chen J, Zhou YB, Chen M, Guo J, Ma YZ, Wei WL, Xu ZS. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family and functional identification of GmGRAS37 in drought and salt tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:604690. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.604690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipps JM. Prospects and limitations for mycorrhizas in biocontrol of root pathogens. Can J Bot. 2004;82:1198–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Chen Z, Ahmed N, Han B, Cui Q, Liu A. Genome-wide identification,evolutionary analysis, and stress responses of the GRAS gene family in Castor Beans. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1004. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Liu F, Han G, Wang W, Zhu S, Li X. Improvement of Lotus japonicus hairy root induction and development of a mycorrhizal symbiosis system. Appl Plant Sci. 2017;6:e1141. doi: 10.1002/aps3.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Cui HT, Buer B, Vijayakumar V, Delaux PM, Junkermann S, Bucher M. Network of GRAS transcription factors involved in the control of arbuscule development in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:854. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.255430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Klinnawee L, Zhou Y, Saridis G, Vijayakumar V, Brands M, Dörmann P, Gigolashvili T, Turck F, Bucher M. AP2 transcription factor CBX1 with a specific function in symbiotic exchange of nutrients in mycorrhizal Lotus japonicus. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E9239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812275115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Roy A, Zhang Y. Protein–ligand binding site recognition using complementary binding-specific substructure comparison and sequence profile alignment. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2588–2595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N, Luo D, Zhang X, Liu J, Wang W, Jin Y, Dong W, Liu J, Liu H, Yang W, Zeng L, Li Q, He Z, Oldroyd GE, Wang E. A DELLA protein complex controls the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in plants. Cell Res. 2014;24:130–133. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZL, Ogawa M, Fleet CM, Zentella R, Hu J, Heo JO, Lim J, Kamiya Y, Yamaguchi S, Sun TP. Scarecrow-like 3 promotes gibberellin signaling by antagonizing master growth repressor DELLA in Arabidopsis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2160–2165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012232108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentella R, Zhang Z-L, Park M, Thomas SG, Endo A, Murase K, Fleet CM, Jikumaru Y, Nambara E, Kamiya Y. Global analysis of DELLA direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3037–3057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Heat map representation of three AM-induced GRAS genes belonging to the SCL3 group under different treatment. Data was obtained from Lotus base (https://lotus.au.dk/). The value bar is shown on the right, and red to blue colors represent high to low expression levels.

Figure S3 Gene structure of LjGRAS36 in wild type Lotus japonicus and ljgras36 mutant. (A) Gene structure of LjGRAS36 and position of the LORE1a insertion in ljgras36. Gray arrows indicate the LORE1a transposon. (B) Identification of homozygous ljgras36 through genomic DNA amplification. M represents DNA marker. Gifu represents wild type L. japonicus

Figure S2 Conserved amino acids sequence and protein structure of LjGRAS36. (A) Sequence alignment of LjGRAS36, AtSCL3, and SlGRAS18. The identical deduced amino acids were shaded by the red box. Highly conserved regions were indicated by black lines with motif names. (B) The predicted 3D structures of LjGRAS36, AtSCL3, and SlGRAS18 based on template 6kpb.1.A