Abstract

Differentiated thyroid cancer is an indolent cancer with an excellent prognosis when treated adequately. The treatment algorithm is well established and standardized. Surgery followed by radio-iodine treatment has stood the test of time. In the last decade, the paradigm has slightly shifted with newer diagnostic approaches like stimulated thyroglobulin and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies impacting the treatment decisions. The diagnostic whole body radio-iodine scan has also got innovated with the introduction of r-TSH injection protocol wherein the scan is performed while the patient is on thyroxine thereby minimizing patient discomfort. The new RISK-based classification system has resulted in altered treatment algorithms by sub dividing patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. There has also been identification of TWO new class of thyroid cancer patients—radio-iodine-resistant thyroid cancer and TENIS syndrome (thyroglobulin elevated negative iodine scan) patients. Both these groups posed major challenge to treatment and this resulted in incorporation of TARGETED THERAPY based on the mutations that occur in these TWO groups of patients. The introduction of Sorafenib and Lenvatinib has made significant impact on progression-free and overall survival of these patients. The introduction of THYROPET (124-I PET scan) is gaining momentum as an alternative to 123/131-I scans due to high-resolution images on PET scan increasing the detection sensitivity. All the above factors have resulted in paradigm shift in the management of differentiated thyroid cancer patients.

Keywords: Stimulated thyroglobulin (Tg), Recombinant TSH, TENIS syndrome, Targeted therapy

Thyroid cancer is the most debated topic since last 7 decades with respect to surgical approach and post-surgical treatment. Hence, guidelines have been changing on and off as we learnt more and more of biology and molecular profile of thyroid cancer. The existing diagnostic tests have got redefined, new testing approach has got incorporated, new subclass of radio-iodine-resistant patients have been identified, molecular profiling has become mandatory, and new targeted drug therapy has been incorporated in the treatment algorithm. This article gives a brief overview of these new trends.

RISK-Based Classification

Though the AJCC/UICC classification system [1] continues to be the mainstay, the necessity of treatment-oriented classification was increasingly felt by the clinicians. Accordingly, RISK-based classification was introduced. The recently published 2015 ATA guidelines for management of thyroid cancer (32) proposed additional considerations in the initial risk stratification process. These include histopathologic subtype, presence/absence as well as degree of vascular invasion, focality (unifocal versus multifocal), number and size of pathologic regional lymph nodes with metastatic disease, encapsulated versus non-encapsulated tumor, and, if known, BRAF V600E mutation status (in certain situations).

The patients were grouped into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups based upon these additional criteria. The low-risk group would have surgery followed by hormonal suppression and high-risk group would have surgery followed by the radio-iodine therapy. The intermediate-risk group would have surgery with ablative radionuclide therapy. This approach has led to rationalization of post-surgical treatment with avoidance of unnecessary radio-iodine and other therapies.

Stimulated Thyroglobulin

It is a well-established fact that thyroglobulin (Tg) levels in post thyroidectomy setting are a reliable specific marker for differentiated thyroid cancer. The elevated Tg level would suggest presence of active disease. We also learnt that thyroxine suppresses the Tg level even in the presence of active disease. Thus, a patient could have lymphnode metastasis with normal Tg levels while on thyroxine supplementation. This fact gave rise to new concept of “STIMULATED Tg” which means thyroglobulin levels after withdrawal of thyroxin for 3 to 4 weeks which would raise TSH value (30–50uunits/ml) which in turn would stimulate tumor cells growth leading to raised thyroglobulin and this is referred to as STIMULATED Tg [2]. If stimulated Tg is < 1 ng/ml with TSH 50 microunits, then it would be considered negative for significant disease and ideal for observation on thyroxin therapy and radio-iodine scan would not be needed. If stimulated Tg > 1–2 ng/ml, then the patient would need full diagnostic work up and therapy. Thus, stimulated Tg is a good prognostic marker and aids in decision-making (3). The following decision algorithms and cut-off thresholds have been developed for this method of stimulation: Tg < 1.0–2.0 ng/ml–patient in remission (yearly check-up in the course of LT4), Tg ≥ 1.0–2.0 ng/ml but < 10.0 ng/ml–inconclusive result (131I whole body scan every 1–5 years), Tg ≥ 10.0 ng/ml–persistent disease and patient would need full workup and therapy.

Anti-thyroglobulin Antibody

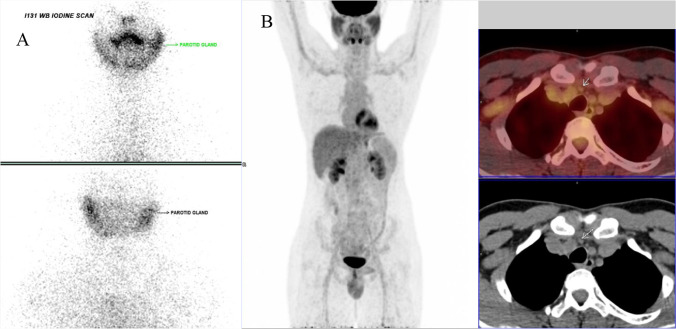

Anti-thyroglobulin antibody levels play specific role in follow-up of differentiated thyroid cancer patients. The presence of high levels of anti Tg Ab in the blood results in binding of thyroglobulin to these antibodies giving falsely low value of Tg even in the presence of active disease. In these patients, the level of anti-thyroglobulin antibody acts as a disease marker (4). Hence, always thyroglobulin and anti Tg Ab should be estimated along with TSH in the follow-up of patient (5). Majority of patients belonging to this group concentrate radio-iodine and are amenable to radio-iodine treatment (Fig. 1). During follow-up, these patients would be assessed on their anti-thyroglobulin antibody level for presence or absence of disease.

Fig. 1.

A Patient with papillary cancer thyroid cancer with raised anti-thyroglobulin antibody and normal thyroglobulin level shows post-op residual thyroid tissue in the neck. B Radio-iodine scan 8 months after 131-I therapy shows complete ablation of neck disease

Recombinant Human Tsh (r-TSH)

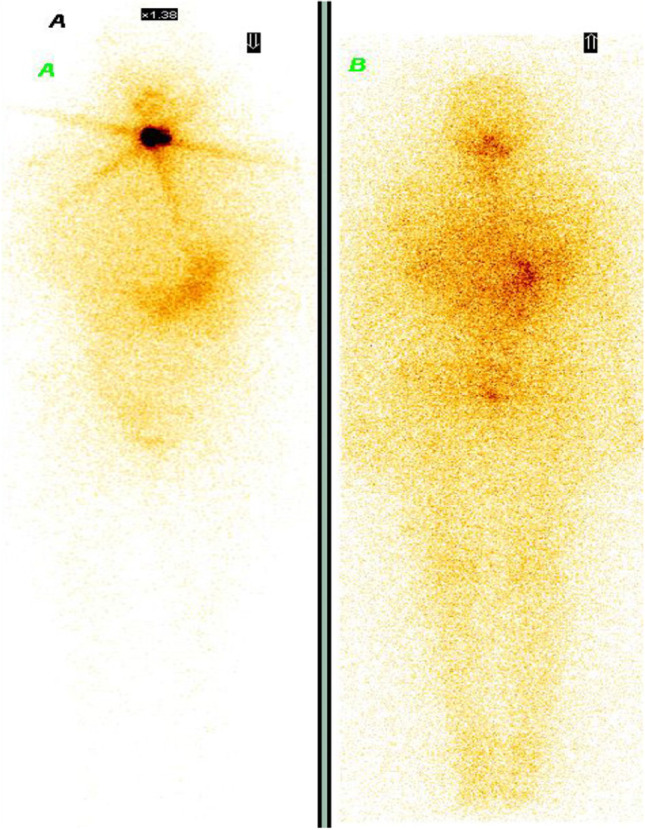

The elevated TSH value (40–0Uiu/ml) is essential for performing 131I scan procedures both in post-surgery and follow-up setting. Hence, thyroxine has to be withdrawn for 3–4 weeks which produces significant discomfort due to hypothyroid symptoms. This has resulted in a new protocol r-TSH OR THYROGEN injection protocol—wherein the patient does NOT stop thyroxin instead the patient is given two injections of r-TSH (Thyrogen) which raises the TSH to 80–150uunits and whole body radio-iodine scan and thyroglobulin level estimations are performed (6). This technique yields similar result as withdrawal of thyroxin for 3–4 weeks (7). This technique helps in avoiding hypothyroid-related discomfort and especially useful in patients where withdrawal of thyroxine is contra indicated. It is also patient friendly as the entire process completes in 1 week. This technique is also employed in radio-iodine treatment for ablation of post-surgical residual tissue in the neck. The results of ablation are similar to withdrawal of thyroxine. There are conflicting reports about the use of r-TSH protocol for radio-iodine treatment of metastatic disease. In one combined study from Canada and the USA, the radio-iodine treatment using r-TSH protocol resulted in 73% of ablation rate (Fig. 2) and 25% improvement in symptoms (8).

Fig. 2.

A Radio-iodine scan after 2 injections of r-TSH shows extensive pulmonary metastases and neck tissue. B Radio-iodine scan 8 months after treatment with 150 millicurie of radio-iodine with TWO injections of r-TSH shows almost complete ablation with TWO residual areas in chest

TENIS Syndrome (Thyroglobulin Elevated Negative Iodine Scan)

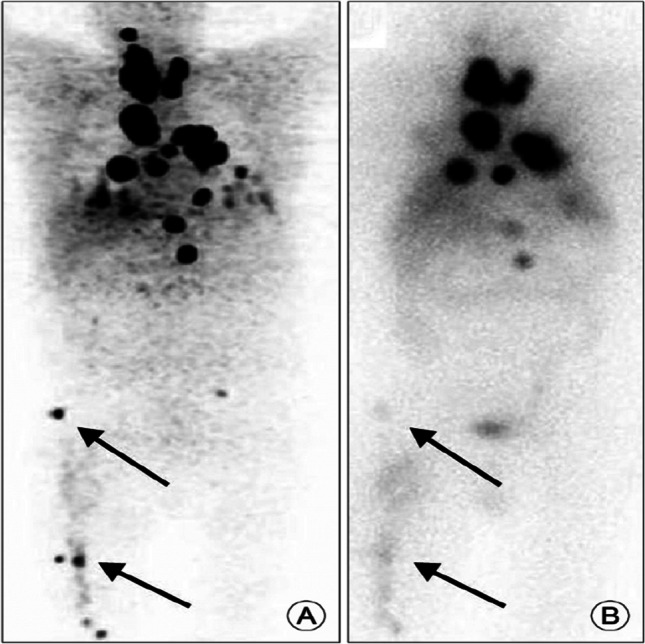

The sodium iodine symporter (NIS) which is situated in the thyrocyte membrane is essential for transporting 131I into the thyroid cancer cell. In 20% of differentiated thyroid cancer patients, the NIS functional integrity is altered and the thyroid cancer cell loses its ability to trap radio-iodine and hence cannot be treated with radio-iodine. These patients are referred to as radio-iodine-resistant patients. Though they are I-131 negative, they retain the property of producing thyroglobulin and hence Tg levels are elevated due to metastatic disease. These patients are grouped under TENIS syndrome ((9). Since the 131I scan can NOT be used in these patients for detecting metastatic sites, they need to undergo FDG PET scan for disease detection along with contrast CT scan (Fig. 3). If localized disease is detected in operable areas, they need to undergo surgery. If there is inoperable disease, then external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) or empirical 131I therapy needs to be instituted (10). The following algorithm is currently recommended for patients with TENIS syndrome.

Fig. 3.

A Post-surgery radio-iodine scan shows NO radio-iodine uptake with Thyroglobulin level of 22 ng/ml and TSH 80 microunits/ml. B FDG PET scan showed right supra clavicular and right paratracheal node abnormality

124I PET Scan

The 124I PET scan is gradually making its way in the diagnostic workup of differentiated thyroid cancers (11). Apart from detecting more lesions due to high-resolution images (Fig. 4), it is found to play major role in 131I Dosimetry calculations for radio-iodine treatment which will enhance the therapeutic efficacy of 131-I treatment (12).

Fig. 4.

124I PET scan [13]. A Pre-therapy 124-I PET scan shows discrete focal lesions in right femur along with neck and mediastinal nodes. B Post therapy 131-I scan shows lesser lesions with diffuse uptake pattern

Targeted Therapy

The patients with TENIS syndrome are NOT amenable to radio-iodine therapy. They are also NOT chemosensitive. In the last 5 years, targeted therapy using tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has found a place in treating this subgroup of radio-iodine-resistant patients.(14) Initially, Sunitinib and Sorafenib were used and currently Lenvatinib is the drug of choice in this patient (14). The patients with TENIS syndrome are known to have altered molecular profile in the form of BRAF, RET, NRAS mutations. Because of this altered molecular profile, they are responsive to TKI treatment. There are new drugs like Debrafenib which are under trial.

The existing data shows 60% improvement in survival and progression-free disease (15). Currently, they are recommended in all symptomatic radio-iodine-resistant patients and in TENIS syndrome (16) with objective proof on imaging (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The chest X-ray and CT scans show regression of pulmonary infiltrates after 6 months of lenvatinib therapy [17]

These drugs are also known to reactivate NIS in 20–50% of patients making them amenable to radio-iodine treatment. However, the current data is limited for any reasonable conclusion.

The above-mentioned new trends have resulted in paradigm shift in the management of thyroid cancers. The emergence of radio-iodine-resistant thyroid cancers and TENIS syndrome has opened up new concepts and rationalized treatment options. The diagnostic workup has undergone considerable changes and targeted therapies are evolving impacting the survival of radio-iodine-resistant thyroid cancers. The otherwise indolent thyroid cancer is challenging us with its new behavioral patterns and future is promising.

Acknowledgements

The images used in this article (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3) are the authors’ own data.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Krishna B.A., Email: drkrish_hinduja@rediffmail.com.

Mohammed Saleel K., Email: saleelmsk@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Tuttle RM, Haugen B, Perrier ND (2017) Updated American Joint Committee on cancer/tumor-node-metastasis staging system for differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancer (eighth edition): what changed and why? Thyroid 27(6):751–756. 10.1089/thy.2017.0102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Pedro Wesley Rosario et al. Is stimulated thyroglobulin necessary after ablation in all patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma and basal thyroglobulin detectable by a second generation assay? Int J Endocrinol. 2015. 796471 5 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Syed Zubir Hussain et al. Preablation stimulated thyroglobulin/TSH ratio as a predictor of successful I-131 remnat ablation in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer following total thyroidectomy. J Thyroid Res 2014 610273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Jo K, et al. Clinical implications of anti-thyroglobulin antibody measurement before surgery in thyroid cancer. Korean J Intern Medicine. 2018;33(6):1050–10576. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spencer CA, et al. Clinical utility of thyroglobulin antibody (TgAb) measurements for patients with differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(12):3615–3627. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Y Krausz , B Uziely, R Nesher, R Chisin, B Glaser (2001). Recombinant thyroid-stimulating hormone in differentiated thyroid cancer. Israel Med Assoc J, December: IMAJ 3(11):843–9 [PubMed]

- 7.Paul W.Ladenson et al. Recombinant thyrotropin versus thyroid hormone withdrawal in evaluating patients with thyroid carcinoma. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 2000 30 2 98–106 April [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Robbins RJ et al (2006) Recombinant human thyrotropin-assisted radioiodine therapy for patients with metastatic thyroid cancer who could not elevate endogenous thyrotropin or be withdrawn from thyroxine. Thyroid 16(11):1121–1130. 10.1089/thy.2006.16.1121 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Khoo Alex Cheen Hoe, et al. A review of TENIS syndrome in Hospital Pulau Pinang. Indian J Nucl Med. 2018;33(4):284–289. doi: 10.4103/ijnm.IJNM_65_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basu S, et al. Defining a rational step-care algorithm for managing thyroid carcinoma patients with elevated thyroglobulin and negative on radioiodine scintigraphy (TENIS): considerations and challenges towards developing an appropriate roadmap. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1167–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha T. T. Phan et al. The diagnostic value of 124 I-PET in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008; 35(5): 958–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lubberink M, et al. The role of (124)I-PET in diagnosis and treatment of thyroid carcinoma. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52(1):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James Nagarajah, Marcel Janssen, Philipp Hetkamp et al. Iodine symporter targeting with 124I/131I theranostics. J Nucl Med Sep 2017 58 (Supplement 2) 34S-38S [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schlumberger M, et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:621–630. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigel Fleeman et al. A systematic review of lenvatinib and sorafenib for treating progressive, locally advanced or metastatic, differentiated thyroid cancer after treatment with radioactive iodine. BMC Cancer. 2019 19 1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Rendl G et al (2020) Real-world data for lenvatinib in radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (RELEVANT): a retrospective multicentric analysis of clinical practice in Austriav. Int J Endocrinol 2020:8834148. 10.1155/2020/8834148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Sheu NW, Jiang HJ, et al. Lenvatinib complementary with radioiodine therapy for patients with advanced differentiated thyroid carcinoma: case reports and literature review. World J Surg Onc. 2019;17:84. doi: 10.1186/s12957-019-1626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]