Abstract

Recently a chromosomal locus possibly specific for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 has been reported that contains a multiple antibiotic resistance gene cluster. Evidence is provided that Salmonella enterica serovar Agona strains isolated from poultry harbor a similar gene cluster including the newly described floR gene, conferring cross-resistance to chloramphenicol and florfenicol.

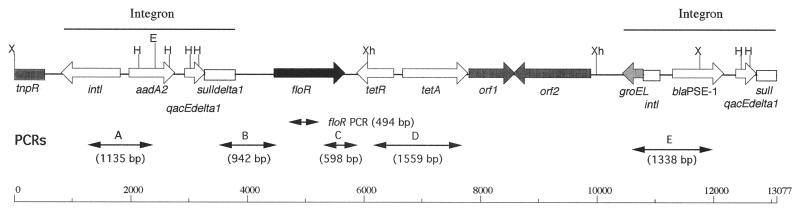

Multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium phage type DT104 has emerged during the last decade as a world health problem because it causes disease in animals and humans (6, 9). The DT104 isolates are mostly resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, spectinomycin, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines (Ap Cm Sm Sp Su Tc antibiotic resistance profile). Recently the genetic basis of these resistances has been elucidated (1, 3, 4, 10, 11). The DT104 strains possess a chromosomal locus of about 12.5 kb carrying all resistance genes, with evidence of two integron structures (Fig. 1) (1, 4). The first integron carries the aadA2 gene, conferring resistance to streptomycin and spectinomycin, and a deletion in the sulI resistance gene. The second one contains the β-lactamase gene blaPSE-1 and a complete sulI gene. Flanked by these two integron structures are the newly described floR gene (1), also called floSt (3), conferring cross-resistance to chloramphenicol and florfenicol, and the tetracycline resistance genes tetR and tetA. This chromosomal locus also carries two putative genes, orf1 and orf2 (Fig. 1), which would code for proteins showing homology to a transcriptional regulator of the LysR family and a transposase-like protein, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Gene organization of the antibiotic resistance gene cluster of serovar Typhimurium DT104 according to Arcangioli et al. (1) and Briggs and Fratamico (4). PCRs used to assess the genetic organization are indicated. Abbreviations for restriction sites: X, XbaI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; Xh, XhoI.

Of particular interest is the newly described floR gene (1, 2, 3, 4). Florfenicol resistance and detection of the floR gene by PCR-based methods have been proposed as means for rapidly identifying multidrug-resistant serovar Typhimurium DT104 strains (3), as phage typing remains a laborious task achievable only in specialized laboratories. Multiplex PCR based on the surrounding genes of the cluster has also been proposed for the identification of DT104 strains (5) or to monitor further evolution of multiresistant serovar Typhimurium strains (2).

Since 1992 increasing numbers of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Agona strains exhibiting the same antibiotic resistance profile as serovar Typhimurium DT104 (Ap Cm Sm Sp Su Tc) have been isolated in Belgium (7). These strains were isolated mainly from poultry. The purpose of the present study was to assess whether these isolates could carry a multidrug resistance gene cluster, comprising the floR gene, similar to the epidemic serovar Typhimurium DT104 strains. We studied at the molecular level five independent isolates from poultry taken at different periods of 1997 and from different areas in Belgium.

Florfenicol resistance and the floR gene.

Antibiograms and MICs of florfenicol were determined as described previously (1, 2). Florfenicol disks and the drug were purchased from Shering-Plough Animal Health (Kenilworth, N.J.). Serovar Typhimurium DT104 strain BN9181 was used as a control (1). The five serovar Agona strains showed resistance to florfenicol to a same extent as serovar Typhimurium DT104 strain BN9181 (MIC of 32 μg/ml). PCR was performed on genomic DNAs using internal primers of the floR gene, cml01 and cml15, as described previously (1). An amplification fragment of the same size as for strain BN9181 (494 bp) was obtained for the five serovar Agona strains (data not shown). Nucleotide sequencing of two of them showed only one nucleotide difference from the published floR nucleotide sequence of serovar Typhimurium DT104, indicating that the serovar Agona strains indeed carry the floR gene.

Multidrug resistance gene cluster.

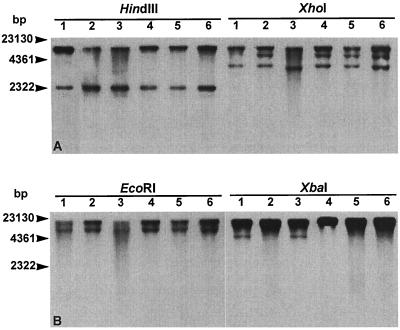

Several PCRs (resulting in amplification fragments A to D [Fig. 1]) were performed on genomic DNAs to assess the genetic environment of the serovar Agona floR gene, in particular the links with the tetR and tetA genes and with the first integron, carrying the aadA2 gene. The presence of the second integron, carrying the blaPSE-1 gene, was also assessed (amplification fragment E [Fig. 1]). Primers used are listed in Table 1. PCR conditions were those described previously (1, 2). Fragments A, C, and D were amplified in a multiplex PCR, whereas fragments B and E were amplified separately. The amplified fragments of the five serovar Agona strains run on agarose gels showed profiles identical to those from serovar Typhimurium DT104 control strain BN9181 (Fig. 2), suggesting the occurrence of a DT104-like antibiotic resistance gene cluster with the two integron structures in the serovar Agona strains. This was further confirmed by Southern blot hybridization of genomic DNA cut by HindIII, EcoRI, XhoI, and XbaI (Appligene, Illkirch, France) with a probe consisting of the XbaI insert of plasmid pSTF3 comprising nearly the entire antibiotic resistance gene cluster of serovar Typhimurium DT104 (1). The probe was labeled with peroxidase by using the ECL direct nucleic acid labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Les Ulis, France). Southern blot hybridization was performed at 42°C according to the manufacturer's instructions. The HindIII and EcoRI profiles of the five serovar Agona strains were identical to those of serovar Typhimurium DT104 control strain BN9181 (Fig. 3). There were slight differences in the XhoI and XbaI profiles, with an additional band detected in some of the serovar Agona strains. The three XhoI bands seen in serovar Agona were expected on the basis of the restriction map of the DT104 antibiotic resistance gene cluster (Fig. 1). However, unexpectedly one of the bands was lacking in control strain BN9181 and in one serovar Agona strain. The EcoRI profile is of particular interest because only one EcoRI site occurs in the 12.5-kb DT104 gene cluster (Fig. 1), and two bands of high molecular mass and of the same size as in serovar Typhimurium DT104 control strain BN9181 were revealed with the XbaI probe in serovar Agona. This probably means that the gene cluster extends over the 12.5 kb described and/or that the insertion site in the chromosome could be the same in serovar Agona as in serovar Typhimurium DT104.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR

| Primer | Gene | Fragmenta | Size (bp) | Nucleotide sequence (5′–3′) | Position in sequenceb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cml01 | floR | 494 | TTTGGWCCGCTMTCRGAC | 4649–4666 | |

| cml15 | floR | SGAGAARAAGACGAAGAAG | 5143–5125 | ||

| int1 | int1 | A | 1,135 | GCTCTCGGGTAACATCAAGG | 1267–1286 |

| aad | aadA2 | GACCTACCAAGGCAACGCTA | 2402–2383 | ||

| sulTER | sulIdelta1 | B | 942 | AAGGATTTCCTGACCCTG | 3567–3584 |

| F3 | floR | AAAGGAGCCATCAGCAGCAG | 4509–4490 | ||

| F4 | floR | C | 598 | TTCCTCACCTTCATCCTACC | 5360–5379 |

| F6 | tetR | TTGGAACAGACGGCATGG | 5958–5940 | ||

| tetR | tetR | D | 1,559 | GCCGTCCCGATAAGAGAGCA | 6205–6224 |

| tetA | tetA | GAAGTTGCGAATGGTCTGCG | 7764–7745 | ||

| int2 | groEL-Int1 | E | 1,338 | TTCTGGTCTTCGTTGATGCC | 10764–10783 |

| pse1 | blaPSE-1 | CATCATTTCGCTCTGCCATT | 12102–12083 |

FIG. 2.

PCR amplifications generating fragments A, B, C, D, and E (Fig. 1) with serovar Typhimurium DT104 strain BN9181 (lanes 2) and serovar Agona strains 31SA96 (lanes 3), 64SA96 (lanes 4), 251SA97 (lanes 5), 959SA97 (lanes 6), and 1873SA97 (lanes 7). Lanes 1, DNA ladder. (A) Amplification generating fragments A, C, and D in multiplex PCR; (B) amplification generating fragment B; (C) amplification generating fragment E.

FIG. 3.

Southern blot hybridization with an XbaI probe (Fig. 1) of HindIII-, XhoI-, EcoRI-, and XbaI-digested genomic DNAs of serovar Typhimurium DT104 strain BN9181 (lanes 1) and serovar Agona strains 31SA96 (lanes 2), 64SA96 (lanes 3), 251SA97 (lanes 4), 959SA97 (lanes 5), and 1873SA97 (lanes 6).

Genomic characterization of the strains.

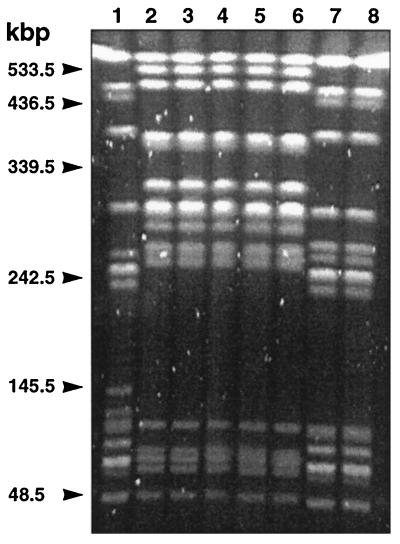

The five serovar Agona strains showed identical pulsotypes in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of their genomic DNAs cut by XbaI, which were clearly distinct from that of serovar Typhimurium DT104 strain BN9181 (Fig. 4), indicating that the serovar Agona isolates were not variants of serovar Typhimurium DT104.

FIG. 4.

PFGE of genomic DNAs cut by XbaI of serovar Typhimurium DT104 strain BN9181 (lane 1); serovar Agona strains 31SA96 (lane 2), 64SA96 (lane 3), 251SA97 (lane 4), 959SA97 (lane 5), and 1873SA97 (lane 6); and serovar Typhimurium DT120 strains 424SA93 (lane 7) and 1439SA96 (lane 8).

Thus, all data indicate that the multidrug-resistant serovar Agona strains harbor a DT104-like antibiotic resistance gene cluster including the newly described floR gene. It seems therefore difficult to base methods of identifying serovar Typhimurium DT104 on florfenicol resistance, detection of the floR gene, or its genetic environment. We have also preliminary evidence that the multidrug resistance gene cluster also occurs on other phage types of serovar Typhimurium, such as DT120, which also showed a pulsotype in PFGE different from that of serovar Typhimurium DT104 (Fig. 4). Furthermore, florfenicol resistance encoded by the floR gene has also recently been revealed in Escherichia coli isolates from diseased cattle (A. Cloeckaert, G. Flaujac, J. L. Martel, and E. Chaslus-Dancla, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 809, 1999).

The discover of a DT104-like antibiotic resistance gene cluster in serovar Agona raises the question of its mobility. Recently it has been shown that the resistance genes of serovar Typhimurium DT104 can be efficiently transduced by P22-like phage ES18 and by phage PDT17, which is released by all DT104 isolates analyzed so far (12). Also upstream of the first integron is a gene encoding a putative resolvase enzyme with more than 50% identity with the Tn3 resolvase family (1), which suggests that the antibiotic resistance gene cluster could form part of a large transposon. Further nucleotide sequencing of the regions up- and downstream the 12.5-kb antibiotic resistance gene cluster is needed to determine if this cluster belongs to a transposon. A functional approach such as that described by Levesque and Jacoby (8) could also be used to determine its possible transposon-mediated mobility.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Mouline for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arcangioli M A, Leroy-Sétrin S, Martel J L, Chaslus-Dancla E. A new chloramphenicol and florfenicol resistance gene flanked by two integron structures in Salmonella typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arcangioli M A, Leroy-Sétrin S, Martel J L, Chaslus-Dancla E. Evolution of chloramphenicol resistance, with emergence of cross-resistance to florfenicol, in bovine Salmonella Typhimurium strains implicates definitive phage type (DT) 104. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:103–110. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-1-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolton L F, Kelley L C, Lee M D, Fedorka-Cray P J, Maurer J J. Detection of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 based on a gene which confers cross-resistance to florfenicol and chloramphenicol. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1348–1351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1348-1351.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs C E, Fratamico P M. Molecular characterization of an antibiotic resistance gene cluster of Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:846–849. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson S A, Bolton L F, Briggs C E, Hurd H S, Sharma V K, Fedorka-Cray P J, Jones B D. Detection of multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium DT104 using multiplex and fluorogenic PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 1999;13:213–222. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1999.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glynn M K, Bopp C, DeWitt W, Dabney P, Mokhtar M, Angulo F J. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 infections in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1333–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imberechts H, D'hooghe I, Pohl P. Prevalence of Salmonella Agona in animals in Belgium. Salmonella Newsl. 1998;4:4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levesque R C, Jacoby G A. Molecular structure and interrelationships of multiresistance β-lactamase transposons. Plasmid. 1988;19:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(88)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poppe C, Smart N, Khakhria R, Johnson W, Spika J, Prescott J. Salmonella typhimurium DT104: a virulent and drug-resistant pathogen. Can Vet J. 1998;39:559–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridley A, Threlfall E J. Molecular epidemiology of antibiotic resistance genes in multiresistant epidemic Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:113–118. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandvang D, Aarestrup F M, Jensen L B. Characterisation of integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in Danish multiresistant Salmonella enterica Typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmieger H, Schicklmaier P. Transduction of multiple drug resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:251–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]