Abstract

Background

Obesity is of grave concern as a comorbidity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). We examined the factors associated with weight gain among Korean adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We conducted an online survey of 1,000 adults (515 men and 485 women aged 20–59 years) in March 2021. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the factors associated with weight gain. The analysis was adjusted for sex, age, region, depressive mood, anxiety, eating out, late-night meals, alcohol consumption, exercise, sleep disturbance, meal pattern, subjective body image, comorbidities, marital status, living alone, and income.

Results

After adjusting for confounding variables, the odds for weight gain increased in the group aged 20–34 years compared with the group aged 50–59 years (1.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–3.32). Women were more associated with the risk of weight gain compared with men. The odds for weight gain increased in the lack of exercise group compared with the exercise group (4.89; 95% CI, 3.09–7.88). The odds for weight gain increased in the eating-out and late-night meal groups compared with that in the groups not eating out and not having late-night meals. Individuals watching a screen for 3–6 hr/day were more associated with the risk of weight gain compared with those who rarely watched a screen. The odds for weight gain increased in participants who considered themselves obese compared with those who did not consider themselves obese.

Conclusion

A healthy diet and regular physical activity tend to be the best approach to reduce obesity, a risk factor for COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Weight gain, Feeding behavior, Sedentary behavior, Weight perception

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and has led to a global pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 200,000 Koreans from the winter of 2019 to July 31, 2021.1 Over 85 million people have been infected by SARS-CoV-2, with 1.8 million deaths worldwide in 2020.2 The World Health Organization recommends physical distancing from other people and avoiding crowds as protective measures against COVID-19. Social distancing is an effective method for preventing the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, many countries have mandated measures such as social distancing and movement restrictions including temporary closure of restaurants, fitness facilities, and other public places to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Some studies have observed changes in health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic.3,4 Curfews and movement restrictions have caused many people to stay indoors, which has led to the heightened stress levels now associated with COVID-19. Previous studies have indicated that the dramatic changes in the lifestyle of Korean adults led to body weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 One cross-sectional study showed that approximately 20% of participants gained 2.3–4.5 kg of body weight during lockdown due to COVID-19.3

Obesity results in deterioration of cardiometabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease,6-9 osteoporosis, and mortality.10 Obesity also increases the susceptibility of COVID-19 and the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.11,12

Some studies in other countries have focused on the factors associated with body weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic.13,14 However, the factors associated with body weight gain among Korean adults during the COVID-19 pandemic are unclear. Therefore, we investigated the factors associated with body weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic among Korean adults (aged 20–59 years) using a questionnaire.

METHODS

Data source and study population

We conducted an online survey using a panel managed by a research company. We included 1,000 individuals (515 men and 485 women, aged 20–59 years). The survey was conducted over a 24-hour period from the 29 March to the March 30, 2021. The questionnaire was developed as part of our study, and its copyright belongs to the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO), which funded our study. All participants received financial incentive equivalent to 5,000 South Korean won (KRW; USD 4.49 as of June 13, 2021).

All participants provided their informed consent prior to participating in the study. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for approval of Institutional Review Board was waived due to retrospective nature of this study.

Assessment of body weight gain

Participants were considered part of the “body weight gain” cohort if they answered, “Body weight gained (more than 3 kg)” to the question, “Have there been any changes in the current body weight because of COVID-19?”

Covariates

The questionnaire included questions on participants’ general characteristics, including sex, age, income, marital status, and other characteristics. We divided the patients into three age groups: 20–34, 35–49, and 50–59 years old. The patients were also divided according to region, namely, Seoul, capital area, regional central city, and others. “Depressive and anxious” as a state was evaluated by the participants based on severity levels from 1 to 10. Severity was then classified according to a scale where 1–4 points meant “low,” 5–6 points meant “middle,” and 7 points or more meant “high.” “Eating-out” and “late-night meals” were divided into four groups: 7 day/wk, 4–6 day/wk, 1–3 day/wk, and rare. Participants were asked whether they drank alcohol; the frequency of alcohol consumption per week and the number of alcoholic drinks consumed per day during the COVID-19 pandemic were evaluated. Men who consumed ≥2 drinks per day and women who consumed ≥1 drink per day were referred to as heavy alcohol drinkers. Regular physical activity was defined more than 3 day/wk. Hours of TV or video material were divided into three groups: ≤2 hr/day, 3–6 hr/day, and ≥7 hr/day. Sleep disturbance was defined as suffering from sleep disturbance that interfered with participants’ daily life. The meal pattern was defined as whether or not they took three meals a day and at a regular hour; participants who ate all three meals at a regular hour were defined as “regular,” those who did not eat both were defined as “irregular,” and the rest were defined as “so-so.” Subjective body image was divided into three groups: underweight, normal, and obese. Regarding history of comorbidities, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, rhinitis, and asthma was recorded among participants. Living alone was defined as “number of people living together: (0).” Monthly personal income levels were divided into three groups: <4,000,000 KRW, 4,000,000–6,999,999 KRW, and ≥7,000,000 KRW. Marital status was categorized into two groups: “never married or separated” and “married.”

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The baseline characteristics of the study participants are presented as numbers and percentages. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. We conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis and calculated the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the factors associated with body weight gain among Korean adults. It was adjusted for sex, age, region, depressive mood, anxiety, eating out, late-night meals, alcohol consumption, exercise, sleep disturbance, meal pattern, subjective body image, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, marital status, living alone, and income. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

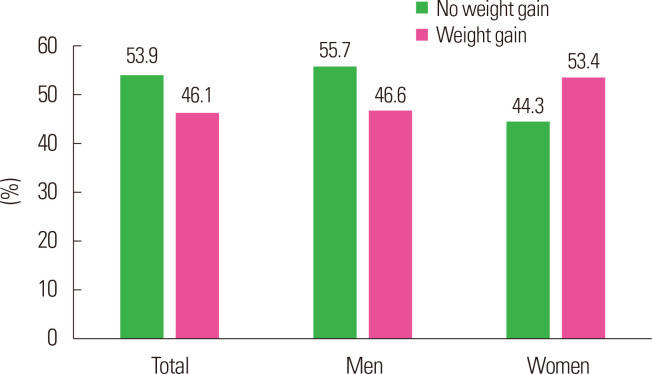

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the 1,000 participants according to weight gain. The mean age was 40.5±10.9 years in the overall group, 41.6±11.3 years in the no weight gain group and 39.1±10.3 years in the weight gain group. The prevalence of participants with high levels of depressive mood and anxiety was significantly higher among the weight gain group. The prevalence of participants eating out more than 4 days/week and late-night meal more than 4 day/wk was significantly higher among the weight gain group. The proportions of “lack of physical activity” and “high hour of watching screen” were 88.9% and 18.4% in the weight gain group, respectively. The percentage of “subjective body image” was 28.0% for normal subjects and 71.1% for obese subjects in the weight gain group. The proportion without underlying diseases was 42.7% in the weight gain group, and the proportion of those with a history of obesity and rhinitis was higher in the weight gain group than in the no weight gain group. The prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus was 15.2%, 11.1%, and 5.8% in the no weight gain group and 14.3%, 11.1%, and 4.1% in the weight gain group, respectively. However, there was no difference in the three diseases between the weight gain group and the no weight gain group. Fig. 1 shows the proportion of individuals in subgroups with body weight gain. Approximately 46.1% of total participants gained body weight during the COVID-19 pandemic; 46.6% of men gained body weight and 53.4% of women gained body weight.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of study participants according to weight gain

| Variable | No weight gain (n = 539) | Weight gain (n = 461) | P | Variable | No weight gain (n = 539) | Weight gain (n = 461) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 41.6 ± 11.3 | 39.1 ± 10.3 | < 0.001 | Hour of watching screen | < 0.001 | |||

| Height (cm) | 168.3 ± 5.8 | 174.2 ± 7.7 | 0.16 | Rare | 223 (43.6) | 124 (27.8) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 68.9 ± 14.0 | 82.0 ± 17.5 | 0.18 | Middle | 212 (41.5) | 240 (53.8) | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 82.2 ± 10.7 | 86.9 ± 10.8 | 0.47 | High | 76 (14.9) | 82 (18.4) | ||

| Region | 0.67 | Sleep disturbance | 0.05 | |||||

| Seoul | 98 (18.2) | 98 (21.3) | No | 511 (94.8) | 422 (91.5) | |||

| Capital area | 181 (33.6) | 146 (31.7) | Yes | 28 (5.2) | 39 (8.5) | |||

| Regional central city | 102 (18.9) | 86 (18.7) | Meal pattern | < 0.001 | ||||

| Others | 158 (29.3) | 131 (28.4) | Regular | 110 (20.4) | 60 (13.0) | |||

| Depressive mood | < 0.001 | So-so | 340 (63.1) | 283 (61.4) | ||||

| Low | 69 (12.8) | 28 (6.1) | Irregular | 89 (16.5) | 118 (25.6) | |||

| Middle | 155 (28.8) | 98 (21.3) | Subjective body image | < 0.001 | ||||

| High | 315 (58.4) | 335 (72.7) | Underweight | 82 (15.2) | 4 (0.9) | |||

| Anxiety | < 0.001 | Normal | 290 (53.8) | 129 (28.0) | ||||

| Low | 164 (30.4) | 80 (17.4) | Obesity | 167 (31.0) | 328 (71.1) | |||

| Middle | 167 (31.0) | 133 (28.9) | Past history | |||||

| High | 208 (38.6) | 248 (53.8) | None | 293 (54.4) | 197 (42.7) | < 0.001 | ||

| Eating out | < 0.001 | Hypertension | 82 (15.2) | 66 (14.3) | 0.76 | |||

| 7 day/wk | 81 (15.0) | 99 (21.5) | Dyslipidemia | 60 (11.1) | 51 (11.1) | 0.99 | ||

| 4–6 day/wk | 130 (24.1) | 179 (38.8) | Diabetes mellitus | 31 (5.8) | 19 (4.1) | 0.30 | ||

| 1–3 day/wk | 162 (30.1) | 118 (25.6) | Obesity | 61 (11.3) | 131 (28.4) | < 0.001 | ||

| Rare | 166 (30.8) | 65 (14.1) | Rhinitis | 98 (18.2) | 126 (27.3) | < 0.01 | ||

| Late-night meal | < 0.001 | Asthma | 13 (2.4) | 16 (3.5) | 0.42 | |||

| 7 day/wk | 15 (2.8) | 19 (4.1) | Marital status | 0.83 | ||||

| 4–6 day/wk | 60 (11.1) | 142 (30.8) | Married | 332 (61.6) | 288 (62.5) | |||

| 1–3 day/wk | 131 (24.3) | 126 (27.3) | Never married or separated | 207 (38.4) | 173 (37.5) | |||

| Rare | 333 (61.8) | 174 (37.7) | Living alone | 0.42 | ||||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.52 | Yes | 71 (13.2) | 52 (11.3) | ||||

| Yes | 176 (42.1) | 173 (44.6) | No | 468 (86.8) | 409 (88.7) | |||

| No | 242 (57.9) | 215 (55.4) | Income (KRW) | 0.26 | ||||

| Physical activity | < 0.001 | < 4,000,000 | 228 (42.3) | 180 (39.0) | ||||

| Yes | 191 (35.4) | 51 (11.1) | 4,000,000–6,999,999 | 197 (36.5) | 192 (41.6) | |||

| No | 348 (64.6) | 410 (88.9) | ≥ 7,000,000 | 114 (21.2) | 89 (19.3) |

Values are presented as mean± standard deviation or number (%).

KRW, South Korean won.

Figure 1.

Proportion of weight gain during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Tables 2 and 3 present the proportion of body weight gain according to sex. The mean ages (in years) of respondents with weight gain were 38.2±10.1 in men and 39.9±10.4 in women. In men, depressive mood, anxiety, eating out, late-night meal, physical activity, hour of watching screen, meal pattern, subjective body image, obesity, and rhinitis showed significant differences between the weight gain group and no weight gain group. The prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus was 20.3%, 14.0%, and 7.0% in the no weight gain group and 22.8%, 14.0%, and 6.0% in the weight gain group, respectively. However, there was no difference in the three diseases between the weight gain group and the no weight gain group. In women, alcohol consumption showed an additional difference, but there was no difference in rhinitis. The prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus was 8.8%, 7.5%, and 4.2% in the no weight gain group and 6.9%, 8.5%, and 2.4% in the weight gain group, respectively. However, there was no difference in the three diseases between the weight gain group and the no weight gain group.

Table 2.

Patterns of weight gain in men

| Variable | No weight gain (n = 300) | Weight gain (n = 215) | P | Variable | No weight gain (n = 300) | Weight gain (n = 215) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 41.8 ± 10.9 | 38.2 ± 10.1 | < 0.001 | Middle | 114 (39.9) | 106 (50.0) | ||

| Region | 0.80 | High | 29 (10.1) | 28 (13.2) | ||||

| Seoul | 54 (18.0) | 44 (20.5) | Sleep disturbance | 0.13 | ||||

| Capital area | 99 (33.0) | 69 (32.1) | No | 288 (96.0) | 199 (92.6) | |||

| Regional central city | 54 (18.0) | 42 (19.5) | Yes | 12 (4.0) | 16 (7.4) | |||

| Others | 93 (31.0) | 60 (27.9) | Meal pattern | 0.02 | ||||

| Depressive mood | < 0.01 | Regular | 72 (24.0) | 31 (14.4) | ||||

| Low | 49 (16.3) | 19 (8.8) | So-so | 186 (62.0) | 146 (67.9) | |||

| Middle | 88 (29.3) | 45 (20.9) | Irregular | 42 (14.0) | 38 (17.7) | |||

| High | 163 (54.3) | 151 (70.2) | Subjective body image | < 0.001 | ||||

| Anxiety | < 0.01 | Underweight | 42 (14.0) | 2 (0.9) | ||||

| Low | 105 (35.0) | 46 (21.4) | Normal | 164 (54.7) | 53 (24.7) | |||

| Middle | 87 (29.0) | 67 (31.2) | Obesity | 94 (31.3) | 160 (74.4) | |||

| High | 108 (36.0) | 102 (47.4) | Past history | |||||

| Eating out | < 0.001 | None | 159 (53.0) | 84 (39.1) | < 0.001 | |||

| 7 day/wk | 55 (18.3) | 49 (22.8) | Hypertension | 61 (20.3) | 49 (22.8) | 0.57 | ||

| 4–6 day/wk | 78 (26.0) | 86 (40.0) | Dyslipidemia | 42 (14.0) | 30 (14.0) | 0.99 | ||

| 1–3 day/wk | 88 (29.3) | 54 (25.1) | Diabetes mellitus | 21 (7.0) | 13 (6.0) | 0.80 | ||

| Rare | 79 (26.3) | 26 (12.1) | Obesity | 40 (13.3) | 71 (33.0) | < 0.001 | ||

| Late-night meal | < 0.001 | Rhinitis | 43 (14.3) | 59 (27.4) | < 0.001 | |||

| 7 day/wk | 15 (5.0) | 9 (4.2) | Asthma | 7 (2.3) | 6 (2.8) | 0.97 | ||

| 4–6 day/wk | 35 (11.7) | 73 (34.0) | Marital status | 0.99 | ||||

| 1–3 day/wk | 78 (26.0) | 60 (27.9) | Married | 177 (59.0) | 127 (59.1) | |||

| Rare | 172 (57.3) | 73 (34.0) | Never married or separated | 123 (41.0) | 88 (40.9) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.70 | Living alone | 0.57 | |||||

| Yes | 124 (48.8) | 87 (46.5) | Yes | 50 (16.7) | 31 (14.4) | |||

| No | 130 (51.2) | 100 (53.5) | No | 250 (83.3) | 184 (85.6) | |||

| Physical activity | < 0.001 | Income (KRW) | 0.06 | |||||

| Yes | 106 (35.3) | 28 (13.0) | < 4,000,000 | 133 (44.3) | 85 (39.5) | |||

| No | 194 (64.7) | 187 (87.0) | 4,000,000–6,999,999 | 101 (33.7) | 94 (43.7) | |||

| Hour of watching screen | 0.01 | ≥ 7,000,000 | 66 (22.0) | 36 (16.7) | ||||

| Rare | 143 (50.0) | 78 (36.8) |

Values are presented as mean± standard deviation or number (%).

KRW, South Korean won.

Table 3.

Patterns of weight gain in women

| Variable | No weight gain (n = 215) | Weight gain (n = 246) | P | Variable | No weight gain (n = 215) | Weight gain (n = 246) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 41.3 ± 11.8 | 39.9 ± 10.4 | 0.18 | Middle | 98 (43.6) | 134 (57.3) | ||

| Region | 0.68 | High | 47 (20.9) | 54 (23.1) | ||||

| Seoul | 44 (18.4) | 54 (22.0) | Sleep disturbance | 0.36 | ||||

| Capital area | 82 (34.3) | 77 (31.3) | No | 223 (93.3) | 223 (90.7) | |||

| Regional central city | 48 (20.1) | 44 (17.9) | Yes | 16 (6.7) | 23 (9.3) | |||

| Others | 65 (27.2) | 71 (28.9) | Meal pattern | 0.01 | ||||

| Depressive mood | 0.01 | Regular | 38 (15.9) | 29 (11.8) | ||||

| Low | 20 (8.4) | 9 (3.7) | So-so | 154 (64.4) | 137 (55.7) | |||

| Middle | 67 (28.0) | 53 (21.5) | Irregular | 47 (19.7) | 80 (32.5) | |||

| High | 152 (63.6) | 184 (74.8) | Subjective body image | < 0.001 | ||||

| Anxiety | < 0.001 | Underweight | 40 (16.7) | 2 (0.8) | ||||

| Low | 59 (24.7) | 34 (13.8) | Normal | 126 (52.7) | 76 (30.9) | |||

| Middle | 80 (33.5) | 66 (26.8) | Obesity | 73 (30.5) | 168 (68.3) | |||

| High | 100 (41.8) | 146 (59.3) | Past history | |||||

| Eating out | < 0.001 | None | 134 (56.1) | 113 (45.9) | 0.03 | |||

| 7 day/wk | 26 (10.9) | 50 (20.3) | Hypertension | 21 (8.8) | 17 (6.9) | 0.55 | ||

| 4–6 day/wk | 52 (21.8) | 93 (37.8) | Dyslipidemia | 18 (7.5) | 21 (8.5) | 0.81 | ||

| 1–3 day/wk | 74 (31.0) | 64 (26.0) | Diabetes mellitus | 10 (4.2) | 6 (2.4) | 0.41 | ||

| Rare | 87 (36.4) | 39 (15.9) | Obesity | 21 (8.8) | 60 (24.4) | < 0.001 | ||

| Late-night meal | < 0.001 | Rhinitis | 55 (23.0) | 67 (27.2) | 0.33 | |||

| 7 day/wk | 0 | 10 (4.1) | Asthma | 6 (2.5) | 10 (4.1) | 0.48 | ||

| 4–6 day/wk | 25 (10.5) | 69 (28.0) | Marital status | 0.97 | ||||

| 1–3 day/wk | 53 (22.2) | 66 (26.8) | Married | 155 (64.9) | 161 (65.4) | |||

| Rare | 161 (67.4) | 101 (41.1) | Never married or separated | 84 (35.1) | 85 (34.6) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.04 | Living alone | 0.99 | |||||

| Yes | 52 (31.7) | 86 (42.8) | Yes | 21 (8.8) | 21 (8.5) | |||

| No | 112 (68.3) | 115 (57.2) | No | 218 (91.2) | 225 (91.5) | |||

| Physical activity | < 0.001 | Income (KRW) | 0.92 | |||||

| Yes | 85 (35.6) | 23 (9.3) | < 4,000,000 | 95 (39.7) | 95 (38.6) | |||

| No | 154 (64.4) | 223 (90.7) | 4,000,000–6,999,999 | 96 (40.2) | 98 (39.8) | |||

| Hour of watching screen | < 0.01 | ≥ 7,000,000 | 48 (20.1) | 53 (21.5) | ||||

| Rare | 80 (35.6) | 46 (19.7) |

Values are presented as mean± standard deviation or number (%).

KRW, South Korean won.

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis. After adjusting for confounding variables, the odds of all weight gain categories increased in the group aged 20–34 years compared with the group aged 50–59 years (OR for weight gain, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.01–3.32). Women were associated with the risk of weight gain compared with men (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.10–2.41). The odds for weight gain increased in the eating-out group (2.59, 1.40–4.82 in the group at 7 day/wk; 2.24, 1.30–3.90 in the group at 4–6 day/wk; and 1.92, 1.11–3.32 in the group in 1–3 day/wk vs. group without eating out). The odds for weight gain increased in the late-night meal group (3.01; 95% CI, 1.82–5.05 in the group 4–6 day/wk and 1.56; 95% CI, 1.00–2.24 in the group 1–3 day/wk vs. group without late-night meal group). The odds for weight gain increased in the group of lack of exercise compared with the group of exercise (4.89; 95% CI, 3.09–7.88). Individuals watching a screen for 3–6 hr/day were more associated with the risk of weight gain compared with those who rarely watched the screen (2.10; 95% CI, 1.40–3.16). The odds for weight gain increased in participants who considered themselves obese compared with those who did not consider themselves obese (4.09; 95% CI, 2.83–5.98).

Table 4.

Multivariate odds ratio and 95% CI for weight gain

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Hour of watching screen | |||||

| Men | 1 | Rare | 1 | |||

| Women | 1.62 (1.10–2.41) | 0.016 | Middle | 2.10 (1.40–3.16) | < 0.001 | |

| Age (yr) | High | 1.48 (0.84–2.62) | 0.171 | |||

| 20–34 | 1.82 (1.01–3.32) | 0.049 | Sleep disturbance | |||

| 35–49 | 1.13 (0.71–1.81) | 0.597 | No | 1 | ||

| 50–59 | 1 | Yes | 1.78 (0.85–3.87) | 0.134 | ||

| Region | Meal pattern | |||||

| Seoul | 1 | Regular | 1 | |||

| Capital area | 0.85 (0.51–1.42) | 0.546 | So-so | 1.09 (0.64–1.87) | 0.745 | |

| Regional central city | 1.27 (0.71–2.27) | 0.422 | Irregular | 1.18 (0.62–2.22) | 0.613 | |

| Others | 1.19 (0.70–2.04) | 0.525 | Subjective body image | |||

| Depressive mood | Underweight | 0.02 (0–0.11) | < 0.001 | |||

| Low | 1 | Normal | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.52 (0.71–3.31) | 0.283 | Obesity | 4.09 (2.83–5.98) | < 0.001 | |

| High | 1.69 (0.80–3.64) | 0.172 | Hypertension | |||

| Anxiety | No | 1 | ||||

| Low | 1 | Yes | 0.90 (0.53–1.52) | 0.690 | ||

| Middle | 1.11 (0.65–1.91) | 0.697 | Dyslipidemia | |||

| High | 1.35 (0.79–2.33) | 0.293 | No | 1 | ||

| Eating-out | Yes | 0.99 (0.53–1.83) | 0.969 | |||

| 7 day/wk | 2.59 (1.40–4.82) | 0.003 | Diabetes mellitus | |||

| 4–6 day/wk | 2.24 (1.30–3.90) | 0.004 | No | 1 | ||

| 1–3 day/wk | 1.92 (1.11–3.32) | 0.020 | Yes | 0.46 (0.19–1.07) | 0.074 | |

| Rare | 1 | Marital status | ||||

| Late-night meal | Married | 1 | ||||

| 7 day/wk | 1.60 (0.62–4.34) | 0.337 | Never married or separated | 0.85 (0.50–1.45) | 0.550 | |

| 4–6 day/wk | 3.01 (1.82–5.05) | < 0.001 | Living alone | |||

| 1–3 day/wk | 1.56 (1.00–2.44) | 0.049 | Yes | 1.42 (0.74–2.75) | 0.293 | |

| Rare | 1 | No | 1 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Income (KRW) | |||||

| Yes | 0.89 (0.60–1.31) | 0.551 | < 4,000,000 | 0.87 (0.52–1.47) | 0.615 | |

| No | 1 | 4,000,000–6,999,999 | 1.11 (0.68–1.83) | 0.667 | ||

| Exercise | ≥ 7,000,000 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||||

| No | 4.89 (3.09–7.88) | < 0.001 |

The results were calculated by multivariable logistic regression analysis after adjustment for sex, age, region, depressive mood, anxiety, eating out, late-night meals, alcohol consumption, exercise, sleep disturbance, meal pattern, subjective body image, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, marital status, living alone, and income.

CI, confidence interval; KRW, South Korean won.

DISCUSSION

Our study explored the factors associated with body weight gain among Korean adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. The odds of weight gain increased in the group aged 20–34 years compared with the group aged 50–59 years. In addition, the odds of weight gain increased by four-fold in participants who thought they were obese compared with those who thought they were of normal weight. Sex, eating out, late-night meals, physical activity, and hours of watching the screen were associated with weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A prior study showed that previous overweight or obesity status in females was associated with weight gain during the lockdown due to COVID-19 in Spain.13 In the Spanish study, the risk of weight gain during lockdown was nine times higher in women than in men. In a study in the United States, 23% of women and 13% of men gained more than 20 kg.10 The increased risk of weight gain in women is attributed to their small body size and low caloric requirements.15 In addition, as shown in Tables 2 and 3, women had higher proportions of late-night eating, anxiety, and depression than men. As seen in a previous study, weight gain increases in people with a body mass index ≥25 kg/m2 compared to people with normal weight.16 Individuals with obesity have a higher risk of anxiety, excess calorie intake, and craving of food than individuals with normal weight.4

Regarding dietary habits, the risk of weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic increased as the number of eating out events or late night meals increased. Eating-out meals tend to include higher energy, macronutrient content, and sodium and were lower energy in fruits and vegetables than home-cooked foods; these dietary behaviors have negative effects on nutrition, obesity, and overweight status.17,18 In addition, late-night meals have a higher propensity to be stored in adipose tissue.19 Our study showed that sedentary behavior, which includes physical inactivity and longer hours of watching the screen, is associated with a decrease in the basal metabolic correction factor by 10%–50%.20 Increase in aerobic exercise reduces cravings for high-calorie foods and increases cognitive restraint among inactive men.21 Previous studies have shown that higher levels of physical activity reduce body mass21 and cardiovascular mortality.22

Other studies have reported that high levels of psychological variables cause craving and intake of unhealthy foods and snacks.23,24 However, our study showed that depressive mood, anxiety, and sleep disturbance were not associated with weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some reports shown that individuals with high levels of stress lost weight during the COVID-19 lockdown.14 In addition, because our study was conducted through a questionnaire, the intensity of depressive mood and anxiety might not have been accurately measured.

An effect of obesity on the severity of COVID-19 has been identified.25-27 Mortality due to COVID-19 increased in patients with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2.28 Therefore, efforts to prevent obesity and weight gain are necessary if the COVID-19 pandemic persists. The KSSO devised a method for weight management during the COVID-19 pandemic by distributing a health diary to help obese patients manage their lifestyle, with a focus on dietary habits and physical activity. The U.K. Government developed guidelines for managing obese people and COVID-19 recovery plans that are in frequent contact with the healthcare system.29 Other studies have shown that social support decreases the risk of weight gain30 and lack of physical activity.31,32 Conducting home-based exercises changes habits, altering behavior in individuals who were encouraged to alter their sedentary behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic.33 Therefore, the support of individuals, the medical community, and governments is needed to prevent people from gaining weight and prevent obesity.

Our study had several limitations. First, there was no representation of Korean adults using a panel of online research companies and it is a small study. Second, our study was based on a self-reported online survey and may have been subject to recall or measurement bias. Third, our study did not consider some confounding variables, such as participants’ body weight, body mass index, speed of weight gain, and smoking status, because they were not included in the questionnaire. Finally, because our study was a cross-sectional study, it could not explain causal associations between lifestyle factors and weight gain among adults. Despite these limitations, our study found that some dietary habits and physical activity were associated with body weight gain among adults aged 20–59 years during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In conclusion, we clarified the factors associated with body weight gain among Korean adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. We showed that eating out, late-night meals, lack of physical activity, hours spent watching a screen each day, and subjective body image were associated with body weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic. If the COVID-19 pandemic persists, adults will need to prevent weight gain and obesity by improving their lifestyle. Further research is needed to elucidate the effects of body weight gain during the COVID-19 pandemic through large-scale data collection. To prevent weight gain during this pandemic, doctors and governments will have to devise methods and guidelines. Managing people’s health with a healthy diet and practical and accessible physical activity seems to be the best way to reduce obesity, which is a risk factor for COVID-19. By preventing weight gain and obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and complications associated with the development of obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic can be prevented. In addition, we need academic societies and associations to prevent and manage obesity and metabolic syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic.34

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: YIH, JHL, BYK, JHK, JWK, HMK, MKL, JHH, DC, JB, KHL, and JYK; acquisition of data: JHL, CBL, BYK, SHY, JHK, and JWK; analysis and interpretation of data: YIH, YH, JHL, and BYK; drafting of the manuscript: YIH and YH; critical revision of the manuscript: YIH and YH; statistical analysis: YH and JHH; obtained funding: JHL, CBL, and SHY; administrative, technical, or material support: JHH and DC; and study supervision: JHL, CBL, and BYK.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization, author. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2020. Timeline of WHO's response to COVID‐19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–4. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zachary Z, Brianna F, Brianna L, Garrett P, Jade W, Alyssa D, et al. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14:210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flanagan EW, Beyl RA, Fearnbach SN, Altazan AD, Martin CK, Redman LM. The impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021;29:438–45. doi: 10.1002/oby.23066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearl RL. Weight stigma and the "Quarantine-15". Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1180–1. doi: 10.1002/oby.22850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black E, Holst C, Astrup A, Toubro S, Echwald S, Pedersen O, et al. Long-term influences of body-weight changes, independent of the attained weight, on risk of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22:1199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Duration of overweight and metabolic health risk in American men and women. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:585–91. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truesdale KP, Stevens J, Lewis CE, Schreiner PJ, Loria CM, Cai J. Changes in risk factors for cardiovascular disease by baseline weight status in young adults who maintain or gain weight over 15 years: the CARDIA study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1397–407. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohn M, Koo BK, Yoon HI, Song KH, Kim ES, Kim HB, et al. Impact of COVID-19 and associated preventive measures on cardiometabolic risk factors in South Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2021;30:248–60. doi: 10.7570/jomes21046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y, Manson JE, Yuan C, Liang MH, Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, et al. Associations of weight gain from early to middle adulthood with major health outcomes later in life. JAMA. 2017;318:255–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, Raverdy V, Noulette J, Duhamel A, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1195–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York city area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sánchez E, Lecube A, Bellido D, Monereo S, Malagón MM, Tinahones FJ, et al. Leading factors for weight gain during COVID-19 lockdown in a Spanish population: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2021;13:894. doi: 10.3390/nu13030894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhutani S, vanDellen MR, Cooper JA. Longitudinal weight gain and related risk behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in adults in the US. Nutrients. 2021;13:671. doi: 10.3390/nu13020671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meldrum DR, Morris MA, Gambone JC. Obesity pandemic: causes, consequences, and solutions-but do we have the will? Fertil Steril. 2017;107:833–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summerbell CD, Douthwaite W, Whittaker V, Ells LJ, Hillier F, Smith S, et al. The association between diet and physical activity and subsequent excess weight gain and obesity assessed at 5 years of age or older: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33 Suppl 3:S1–92. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SY, Kang M. Male Korean workers eating out at dinner. Br Food J. 2018;120:1832–43. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-12-2017-0680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scourboutakos MJ, L'Abbé MR. Restaurant menus: calories, caloric density, and serving size. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tu BP, Kudlicki A, Rowicka M, McKnight SL. Logic of the yeast metabolic cycle: temporal compartmentalization of cellular processes. Science. 2005;310:1152–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1120499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amaro-Gahete FJ, Jurado-Fasoli L, De-la-O A, Gutierrez Á, Castillo MJ, Ruiz JR. Accuracy and validity of resting energy expenditure predictive equations in middle-aged adults. Nutrients. 2018;10:1635. doi: 10.3390/nu10111635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocha J, Paxman J, Dalton C, Winter E, Broom DR. Effects of a 12-week aerobic exercise intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, and 7-day energy intake and energy expenditure in inactive men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:1129–36. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang J, Wylie-Rosett J, Cohen HW, Kaplan RC, Alderman MH. Exercise, body mass index, caloric intake, and cardiovascular mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:283–9. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moynihan AB, van Tilburg WA, Igou ER, Wisman A, Donnelly AE, Mulcaire JB. Eaten up by boredom: consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Front Psychol. 2015;6:369. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao A, Grilo CM, White MA, Sinha R. Food cravings mediate the relationship between chronic stress and body mass index. J Health Psychol. 2015;20:721–9. doi: 10.1177/1359105315573448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flint SW, Tahrani AA. COVID-19 and obesity-lack of clarity, guidance, and implications for care. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:474–5. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30156-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popkin BM, Du S, Green WD, Beck MA, Algaith T, Herbst CH, et al. Individuals with obesity and COVID-19: a global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e13128. doi: 10.1111/obr.13128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stefan N, Birkenfeld AL, Schulze MB, Ludwig DS. Obesity and impaired metabolic health in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:341–2. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0364-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Public Health England, author. Public Health England; London: 2020. Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albury C, Strain WD, Brocq SL, Logue J, Lloyd C, Tahrani A, et al. The importance of language in engagement between health-care professionals and people living with obesity: a joint consensus statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:447–55. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cattell V. Poor people, poor places, and poor health: the mediating role of social networks and social capital. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1501–16. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim D, Subramanian SV, Gortmaker SL, Kawachi I. US state- and county-level social capital in relation to obesity and physical inactivity: a multilevel, multivariable analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1045–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franzini L, Elliott MN, Cuccaro P, Schuster M, Gilliland MJ, Grunbaum JA, et al. Influences of physical and social neighborhood environments on children's physical activity and obesity. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:271–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ricci F, Izzicupo P, Moscucci F, Sciomer S, Maffei S, Di Baldassarre A, et al. Recommendations for physical inactivity and sedentary behavior during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020;8:199. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CB Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Obesity, author. Public statement on the importance of prevention and management of obesity and metabolic syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2021;30:194–5. doi: 10.7570/jomes21064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]