Abstract

Verrucous carcinoma is a histopathological type of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, clinically characterized by slow and continuous growth, having a local destructive character, but low metastasis potential. Condyloma acuminatum is a sexually transmitted infection caused mainly by subtypes 6 and 11 of HPV, with subtypes 16, 18 being involved in malignant transformation. We present the case of a 70-year-old woman, hospitalized for a vulvar and perineal vegetative, ulcerated, bleeding tumor, with onset 20 years ago. The therapeutic option was surgical excision of the lesions and long-term oncological monitoring.

Keywords: Verrucous vulvar carcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, condyloma acuminatum, HPV

Introduction

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is a squamous cell carcinoma with a high degree of differentiation, which can interest, both, the skin and mucous membranes.

According to the WHO classification of the tumors, verrucous carcinoma presents the following clinical forms: oral florid papillomatosis (Ackerman verrucous carcinoma), papillomatosis cutis carcinoides (verrucous carcinoma with a different localization than those of the plantar, oral cavity, genital and perianal area), epithelioma cuniculatum (plantar verrucous carcinoma) and giant condyloma acuminatum of Bushcke-Löwenstein [1,2].

The Buschke-Löwenstein tumor (BLT) was first described by Buschke and Löwenstein who called it "condyloma acuminata carcinoma-like"; in 1979 Mohs and Sahl proposed the inclusion of BLT among the clinical entities of verrucous carcinoma [1,6].

In the etiopathogenesis of VC, several factors intervene, without the possibility to specify exactly which of them initiates the appearance of this form of squamous carcinoma.

The occurrence in the presence of chronic inflammatory phenomena (osteomyelitis fistulas, ulcers, scars, necrobiosis lipoidica), repeated microtraumas, viral etiology (HPV), exposure to chemical carcinogens has been reported [1,2,3].

In genital localization, in male, are considered as risk factors the lack of circumcision and poor hygiene [4].

The most common localizations are at the level of the oral cavity, the anogenital region, the plantar tegument, but other localizations have also been described [2,4].

Anogenital location is sometimes lately diagnosed due to the delayed presentation, caused by the patient embarrassment [5].

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman, phototype III, underweight (BMI 17,1), from the urban area, without significant family medical and pathological history, presented in outpatient dermatology setting for the presence at the genital area of an ulcerated, macerated vegetative lesion, with local inflammatory phenomena. The patient refuses hospitalization requesting local treatment. It was recommended local toilet with antiseptics, and ointment applications with extract from the leaves of green tea 3 times a day and cream with isoconazole nitrate/diflucortholone valerate. The symptomatology diminishes, but at the second control, insisting on the fact that local therapies do not influence the evolution of the lesions and due to the clinical suspicion of a malignant lesions, the patient accepts the admission in the Dermatology Clinic.

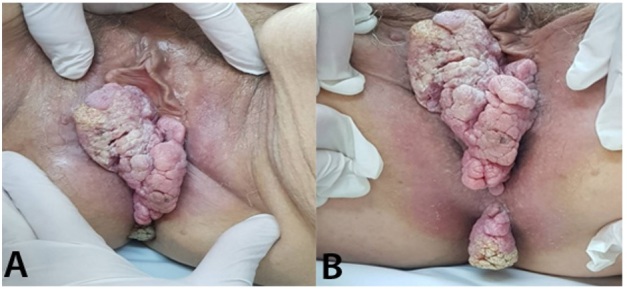

The dermatological examination reveals a vegetative tumor, cauliflower-like, size 15/5cm, pink-whitish color; the lesion was well delineated, furrowed by grooves, of elastic consistency, with macerated surface, painful spontaneously and on palpation. The lesion had a tendency to bleed, and it was located at the level of the right labia majora and the posterior vulvar commissure, accompanied by a fetid odor; a second cauliflower-like pediculated tumor, 4/3cm, with keratotic surface was located at the level of the perineum, protruding between the buttocks (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vegetative, verrucous tumor cauliflower-like located at the level of the right labia majora and the posterior vulvar commissure; B. Vulvar verrucous carcinoma and perineal pedunculated tumor with the keratotic surface

The onset was about 20 years ago, through genital warts. The patient reports that she did not present to the doctor for embarrassment reasons.

Laboratory (C-reactive Protein, GOT, GPT, creatinine, urea, glycemia, complete blood count) were within normal limits, except for erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 50mm/h. Anti-HIV antibodies had a negative result, also VDRL-negative, and TPHA-negative.

The gynecological examination describes a vegetative tumor, mobile on the deep planes, without damage to the bladder, rectum or vaginal mucosa.

The patient was transferred to the Gynecology clinic in order to excise the tumor and establish the diagnosis.

Imaging (thoracic X-ray, abdominal and pelvic ultrasound) were normal, without lymphadenopathies; abdominal and pelvic contrast-MRI also failed to identify abdominal and pelvic enlarged lymph nodes, without pathological contrast intakes at the pelvic level.

The surgical treatment was represented by the excision of the tumor at the level of the right labia and the posterior vulvar commissure with safety edges of 2cm, except for the lesion in the vicinity of the external anal sphincter, which was removed at the edge of the tumor to avoid anal sphincter damage, without macroscopic tumoral remnants.

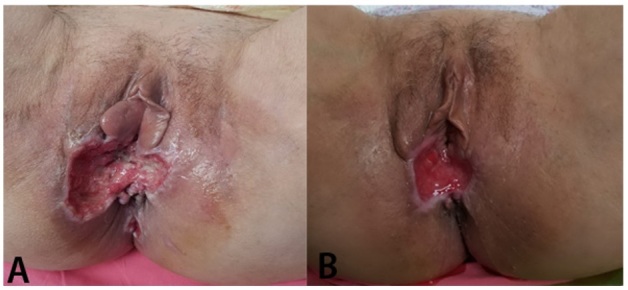

Postoperatively, on the 5th day the dehiscence of the wound occurred, with purulent discharge; bacteriological examination was positive for Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Systemic antibiotherapy was initiated according to the antibiogram, along with local toilet and debridement, the evolution being favorable. At discharge, about 3 weeks from the surgery, the dehiscence wound area was of about 3cm2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Postoperative dehiscence with purulent discharge; B. Dehiscence wound with granulation tissue, aspect at discharge

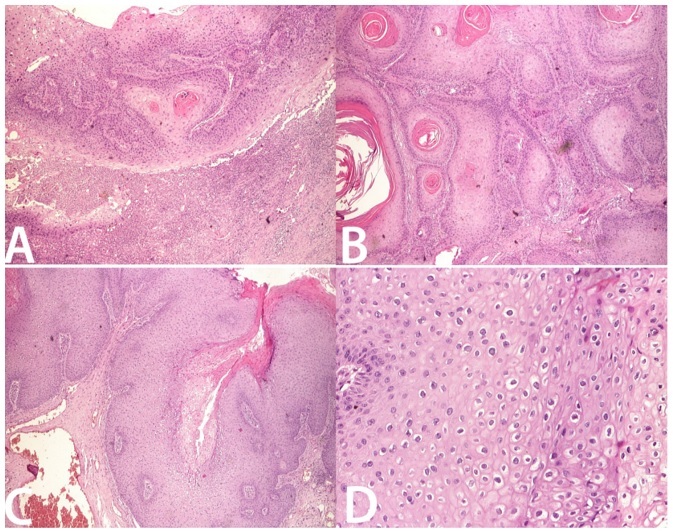

Histopathological examination revealed different aspects depending on the localization of lesions (Tabel 1, Figure 3).

Table 1.

Histopathological aspects related to the tumor location

|

Tumor localization |

Histopathologic aspects |

|

Right labia majora |

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma G1, invasively up to the level of adipose, fibrous connective and muscular tissue |

|

Posterior commissure |

Acanthosis, koilocytosis, hyperkeratosis and low-grade dysplasia |

|

Perineum |

Squamous epithelium with papillomatosis, acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, koilocytosis and low-grade dysplasia |

Figure 3.

Right major labia tumor-well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, invasively in muscular tissue, H&E stain ×20; B. Verrucous carcinoma, H&E stain ×20; C. Posterior commissure tumor-papillomatosis, acanthosis, koilocytosis, hyperkeratosis and low-grade dysplasia H&E stain ×20; D. Perineal tumor-squamous epithelium with koilocytosis, H&E stain ×100

Corroborating the history, clinical, imaging, and histopathological data, the final diagnosis was verrucous vulvar squamous carcinoma. After discharge the patient was referred to the Oncology Department; no chemoradiation therapy was considered.

Two years after the excision the patient does not show recurrence, currently being monitored

Discussions

Vulvar verrucous carcinoma accounts for less than 1% of vulvar cancers; it affects especially postmenopausal women, but at younger ages than those at which invasive squamous cell carcinoma occurs. The management is multidisciplinary and complex in terms of diagnosis and treatment [7].

Verrucous carcinoma occurs mainly in men, with 75% of patients being older than 60 years [2]. Clinical appearance is variable depending on the topographical area.

Giant Bushcke-Lowenstein tumor is the most common form of verrucous carcinoma, affecting mostly men and immunodepressed patients. In men, it is especially located at the glans, penis and foreskin, but it can occur on any ano-urogenital surface. In women, localizations on the vulva, vagina or cervix are encountered. Often is accompanied by inflammatory lymphadenopathy, secondary to the superinfection of the tumor [4,6].

It has a high recurrence rate but has a low incidence of distant metastases [1,2].

BLT has a slow, infiltrating, and destructive evolution, having usually a cauliflower-like aspect; it is often associated with HPV types 6 and 11, in which the oncogenic subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33 may be associated [1,2,4].

It is currently considered that 10-15% of the skin cancers are induced by viruses, involved in carcinogenesis either by introducing viral oncogenes into the DNA of the host cell or by inactivating the host's suppressor genes [8]. HPV DNA is detected in the carcinomas of immunocompetent people in 30-35% of cases, but in immunocompromised people the percentage reaches 75% [8,9].

The role of HPV in skin cancer remains controversial, but there is evidence of the role of the virus in promoting cancer, through the mutagenic effects induced by ultraviolet B radiation. The carcinogenetic process with structural changes in germ cells would pass, as a result, through a first stage of induction of the premalignant state, the malignant conversion being made with the help of cocarcinogens (ultraviolet radiation, smoking, ionizing radiation, chemicals, immunodepression, HIV, herpes simplex virus) [10].

The E6 and E7 proteins encoded by HPV, bind, and inactivate tumor suppressor genes, induce telomerase activity, thus preventing the apoptosis of infected cells. Chronic oxidative stress induced in HPV-infected cells increases susceptibility to DNA damage, thereby promoting cell transformation [8,9,11,12,13,14].

Recent studies suggest a possible role for the release of oxygen free radicals in inflammatory cells in malignant transformation [13].

Depending on the stages of the replicative cycle, viruses may adopt strategies of inhibiting or stimulating apoptosis. Preventing apoptosis is important in establishing viral latency, favoring the survival of latently infected cells. These functions allow the propagation of viral infection in vivo, by blocking apoptosis induced by cytotoxic T cells, so that the virus escapes the destruction mediated by the immune response of the host [1,2,3,15].

Also, the role of Herpes simplex infection in potentiating HPV-induced carcinogenesis has been suggested [16].

The management of patients with verrucous carcinoma is complex, laboratory tests being necessary to establish the patient's general status and the existence of possible immunosuppressive conditions. Preoperative imaging investigations are necessary to diagnose the local invasion and the presence of metastases (Rx, ultrasound, CT, MRI, PET-CT).

The choice of treatment is a challenge depending on the size of the lesion, the perilesional and visceral invasion.

The presence of giant genital warts requires as the first option surgical treatment with histopathological examination, and sometimes immunohistochemical exams.

Histopathological examination is especially important, highlighting the appearance of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Superficial biopsies are not recommended because they reveal aspects similar to those observed in verruca vulgaris. In the presence of clinical suspicion of verrucous carcinoma, it is necessary to perform a deep incisional biopsy in order to be able to highlight the presence of carcinoma. The superficial area of the tumor shows parakeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, protruding granulosa layer. Koilocytosis and low-grade dysplasia may be observed [1,2,4].

Pathologic features are the intradermal, wide, deep tumor proliferations, consisting of well-differentiated keratinocytes with small nuclei with the reduction of inter-rete spaces, some forming sinuses with cysts filled with keratin. The basal membrane is intact, but the tumor extensions push its edges. Frequently, a chronic, diffuse, peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate is observed [1,2,4].

The type of the surgical procedure depends on the size and location of the tumor (surgical excision, hemivulvectomy, or vulvectomy) [7].

The long evolution of the lesions in the presented case, the size of the tumor, the clinical appearance suggestive of malignancy, the general good condition, were arguments for surgical treatment.

A safety edge of at least one cm is recommended to avoid relapses, a principle that has also been observed in our case. For invasive, extensive lesions, large excisions being necessarily followed by grafts or flaps required for local reconstruction [7,17].

In genital localization, in women, the tumor can infiltrate the pelvic organs, but this was not the case in our patient. Rapid growth of the tumor and local invasion are associated with immunodepression, the reported cases occurring in patients with HIV infection, or posttransplantation immunodepression [1,18,19].

Postoperatively, the following complications have been described: local relapse, hemorrhage, wound dehiscence, infection, pain, functional disorders [20].

The dehiscence of the wound was observed in our case, explained by the tumor infection. Healing process required the resolution of the infection, then postoperative wound had a favorable course, one month after the surgery being completely granulated and epithelized.

Hum and the study group published favorable results, with the disappearance of giant condylomatosis, using local treatment with imiquimod 3.5%, but they insist on the importance of the lesion biopsy to precisely exclude malignancy. Other authors associate surgical treatment with imiquimod treatment for any remaining injuries. Although the effectiveness of imiquimod monotherapy in genital warts is recognized, the same cannot be said in giant forms [21].

Although there is no standardized protocol, for small BLT, local, systemic therapies, minimally invasive surgical techniques are associated, and in forms with giant, invasive tumors, surgical treatment is indicated in compliance with oncological principles and functional and aesthetic reconstruction techniques. Excision with oncological safety margins with intraoperative histopathological control decrease the rate of recurrences [17,20].

Chemoradiotherapy may be associated to surgical treatment [22].

Numerous chemotherapeutics have been reported as effective: cisplatin, mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, bleomycin, leucovorin. As for radiation therapy, there is controversy due to the possibility of the appearance of anaplastic forms postradiotherapy, therefore it is associated with chemotherapy and usually precedes surgical treatment [23,24].

For inoperable cases, the association of chemotherapy with targeted therapies (Cetuximab) is proposed. Venter and the study group reported a case of infiltrative giant verrucous carcinoma in the groin and genital area, associated with paraneoplastic hypercalcemia, without metastases, without surgical indication, in which the oncological treatment with pembrolizumab had favorable result [16].

Systemic immunotherapy with interferon alfa after surgical excision has also promising results [17,25].

Identifying the types of viruses involved in carcinogenesis could be of clinical importance through vaccination to prevent the development of malignant tumors.

Early treatment of warts could prevent the development of giant condylomatosis.

It is not possible to specify which condylomas could turn malignant, but there are evidence of the importance of the prophylactic HPV vaccination, and also of the recommendation for vaccination after the treatment of warts [15,19,26,27].

Conclusions

Verrucous carcinoma management is complex, requiring a multidisciplinary team of surgeons (gynecologists, plasticians, generalists), radiotherapists, oncologists, dermatologists, psychologist.

In order to diagnose and highlight the possible metastases, extensive investigations are required: imaging explorations, PET-CT, serial biopsies, immunohistochemistry.

The presented case represents a rare form of verrucous carcinoma with vulvar and perineal localization, with slow evolution but with local destructive potential.

In the development of verrucous carcinoma in the case presented, HPV infection and chronic irritation were implicated.

The diagnosis was delayed due to the lack of attendance at the doctor, being motivated by a deep feeling of embarrassment.

The peculiarity of our case consists in the long evolution of the lesions, the coexistence of vulvar verrucous carcinoma with acuminata condylomas with perineal localization, the lack of immunodepression.

Currently, there are many therapeutic means, but there is a consensus regarding the priority of performing surgical treatment.

Patients require monitoring for a long period of time to diagnose possible relapses or metastases.

Conflict of interests

None to declare.

References

- 1.Lonsdorf A, Hadaschick E. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner A, Enk A, Margolis D, Michael A, Orringer J, editors. New York: McGraw-Hill Education Inc; 2019. Squamous cell carcinoma and Kerathoacanthoma; pp. 1901–1916. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy GF, Beer TW, Cerio R, Kao GF, Nagore E, Pulitzer MP. In: WHO Classification of skin tumours. 4. Elder D, Massi D, Scolyer R, Willemze R, editors. Lyon: IARC Press; 2018. Squamous cell carcinoma; pp. 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahsaini M, Tahiri Y, Tazi MF, Elammari J, Mellas S, Khallouk A, El Fassi MJ, Farih MH, Elfatmi H, Amarti A, Stuurman-Wieringa RE. Verrucous carcinoma arising in an extended giant condyloma acuminatum (Buschke-Löwenstein tumor): A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports. 2013;7:273–273. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinker M, Fenske N, Scalf LA, Glass L. Histologic Variants Of Squamous Cell Carcinoma Of The Skin. Cancer Control. 2001;8(4):354–363. doi: 10.1177/107327480100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong M, Walzman M, Zayyan K, Gupta RD. Verrucous carcinoma - an embarrassing problem. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(8):573–4. doi: 10.1258/095646207781439685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pătraşcu V, Enache O, Ciurea RP. Verrucous Carcinoma - Observations on 4 Cases. Curr Health Sci J. 2016;42(1):102–110. doi: 10.12865/CHSJ.42.01.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bittencourt Campaner A, de Araujo Cardoso F, Fernandes GL, Verrinder Veasey J. Verrucous carcinoma of the vulva: diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(2):243–245. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Münger K, Baldwin A, Edwards K, Hayakawa H, Nguyen C, Owens M, Grace M, Won Huh K. Mechanisms of Human Papillomavirus-Induced Oncogenesis. Journal of Virology. 2004;78(21):11451–11460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11451-11460.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rollison DE, Viarisio D, Amorrortu R, Gheit T, Tommasinoc M. An Emerging Issue in Oncogenic Virology: the Role of Beta Human Papillomavirus Types in the Development of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Virol. 2019;93(7):e01003–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01003-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidry JT, Scott RS. The interaction between human papillomavirus and other viruses. Virus Res. 2017;231:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinbach A, Riemer AB. Immune evasion mechanisms of human papillomavirus: an update. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:224–229. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzenellenbogen R. Telomerase induction in HPV infection and oncogenesis. Viruses. 2017;9(7):v9070180–v9070180. doi: 10.3390/v9070180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marullo R, Werner E, Zhang H, Chen GZ, Shin DM, Doetsch PW. HPV16 E6 and E7 proteins induce a chronic oxidative stress response via NOX2 that causes genomic instability and increased susceptibility to DNA damage in head and neck cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tommasino M. HPV and skin carcinogenesis. Papillomavirus Res. 2019;7:129–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strickley J, Messerschmidt J, Awad M, Li T, Hasegawa T, Ha DT, Nabeta H, Bevins P, Ngo K, Asgari M, Nazarian R, Neel V, Jenson AB, Joh J, Demehri S. Immunity to Commensal Papillomaviruses protects against Skin Cancer. Nature. 2019;575(7783):519–522. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1719-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venter F, Heidari A, Viehweg M, Rivera M, Natarajan P, Cobos E. Giant Condylomata Acuminata of Buschke-Lowenstein Associated With Paraneoplastic Hypercalcemia. JIM-HICR. 2018;6:1–3. doi: 10.1177/2324709618758348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spînu D, Rădulescu A, Bratu O, Checheriţă IA, Ranetti AE, Mischianu D. Giant Condyloma Acuminatum-Buschke-Löwenstein Disease-a Literature Review. Chirurgia. 2014;4(109):445–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Araújo PSR, Guimarães Padilha CE, Soares MF. Buschke-Lowenstein tumor in a woman living with HIV/AIDS. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017;50(4):577–577. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0396-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bastola S, Halalau A, Kc O, Adhikari A. A Gigantic Anal Mass: Buschke-Löwenstein Tumor in a Patient with Controlled HIV Infection with Fatal Outcome. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2018;2018:7267213–7267213. doi: 10.1155/2018/7267213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badiu DC, Manea CA, Mandu M, Chiperi V, Marin IE, Mehedintu C, Popa CC, David OI, Bratila E, Grigorean VT. Giant Perineal Condyloma Acuminatum (Buschke-Löwenstein Tumour): A Case Report. Chirurgia. 2016;5(111):435–438. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.111.5.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hum M, Chow E, Schuurmans N, Dytoc M. Case of giant vulvar condyloma acuminata successfully treated with imiquimod 3.75% cream: A case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2018;6:2050313X18802143–2050313X18802143. doi: 10.1177/2050313X18802143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenoy S, Nittala M, Assaf Y. Anal carcinoma in giant anal condyloma, multidisciplinary approach necessary for optimal outcome: Two case reports and review of Literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11(2):172–180. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HG, Kesey JE, Griswold JA. Giant anorectal condyloma acuminatum of Buschke-Löwenstein presents difficult management decisions. J Surg Case Rep. 2018(4):rjy058–rjy058. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjy058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papapanagiotou IK, Migklis K, Ioannidou G, Xesfyngi D, Kalles V, Mariolis-Sapsakos T, Terzakis E. Giant condyloma acuminatum-malignant transformation. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(4):537–538. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wester NE, Hutten EM, Krikke C, Pol RA. Intra-abdominal localisation of a Buschke-Lowenstein tumour: case presentation and review of the literature. Case Rep Transplant. 2013;18:187682–187682. doi: 10.1155/2013/187682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blomberg M, Dehlendorff C, Munk C, Kjaer SK. Strongly decreased risk of genital warts after vaccination against human papillomavirus: nationwide follow-up of vaccinated and unvaccinated girls in Denmark. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:929–929. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2078–2088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00239-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]