Abstract

This study explored middle- to high income consumers’ awareness and opinions of cause-related marketing and the influences of selected campaign structural elements on consumers’ responses. The study was conducted using qualitative focus groups and a quantitative 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 factorial experiment. A communications approach was adopted to investigate consumer responses to the cause-related marketing communicated campaign itself with education as the beneficiary. The qualitative research revealed that South African consumers are positively disposed toward cause-related marketing in an educational context and that they prefer positive, prosocial campaign messaging. The experiment confirmed that campaign structural elements exert significant independent and interactive influences on consumer intentions, attitudes, and perceptions. A low-involvement product, a specific donation recipient, and a high magnitude actual amount donation were found to have the most significant impact on consumer responses.

Keywords: Cause-related marketing, Campaign structural elements, Education, Qualitative and experimental analyses

Introduction and purpose of the study

For the purposes of this paper cause-related marketing (CRM) is defined as charitable giving of money to an organization that benefits others beyond one’s own family (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). Embedded in the societal marketing domain, CRM requires a network orientation that is based on the principles of responsible marketing (Achrol & Kotler, 2012). In this study the transaction-based approach is investigated. Varadarajan and Menon (1988) point out that a transactional-based approach to CRM connects a firm’s donation directly to their customers’ behaviour.

Nowadays it is expected that firms should be seen as contributing to society and, from a firm’s perspective, creating an alliance whereby they contribute to a charitable cause as a form of societal goodwill. Such an alliance is evidence of a firm’s corporate citizenship and may translate into a favorable corporate image and the enhancement of brand equity (Rim et al., 2016). Woodroof et al. (2019) argue that participation in CRM partnerships can result in improved financial performance of a firm. More and more firms are also publicizing their donations. Lee and Kotler (2013), for instance, estimate that as much as 90% of Fortune 500 firms include their corporate donations in their annual reports. Palmquist (2020) reports that business firms in the United States spent $2.14 billion on CRM in 2018. According to Mendinia et al. (2018), global spending on cause-related sponsorships amounted to $62.7 billion in 2017 and their prediction was that this figure would soon rise to $65.8 billion (IEG, 2018). The environment in which NPOs conduct business has changed over time. Declining numbers of individual donors and the size of their contributions and a growing number of NPOs addressing new challenges such as Covid-19 have intensified their competition for charitable support (Rooney et al., 2018; Sneddon et al., 2020). When choosing a partner for a cause-related marketing campaign, it is important for credibility reasons that the firm’s product offering is congruent with the relevant cause.

Education was chosen as the beneficiary in this study and for several reasons. The South African population is critically aware of the importance of education to enhance their economic and career prospects. Also, the majority had received a relatively low standard of education and school education was often not compulsory for all population groups under the previous political dispensation (Morrow, 1990). The current government has since introduced several policies to widen the reach of education. Education was made compulsory for children up to a certain age and the government has introduced free university education for students from households whose gross income is below a certain level (Sader & Gabela, 2017). The design of this study was based on a number of considerations. Firstly, contributing to charities involved with education seems to be common in several other countries too. For instance, Sneddon et al. (2020) found that, in a study among respondents from Australia and the US, donating to education charities was the most popular choice. Secondly, Zhang et al. (2020) identified 129 studies in which cause-related marketing experiments were used as the methodology. Thirdly, Zhang et al. (2020) found that in most of these studies the products concerned were mainly low cost and low-involvement products and that 18 of the social causes examined dealt with education.

The number of potential campaign structural elements, the multiplicity of their possible permutations, the limited generalizability of earlier studies and the contextual nature of cause-related marketing, have served as justification for further inquiry into the influence of these elements on consumer responses (Lafferty et al., 2016; Howie et al., 2018; Sneddon et al., 2020). The current study is an incremental contribution to this effort.

This study explored the awareness and opinions of South African consumers pertaining to cause-related marketing campaigns (CAREMs’) and assessed the influence of several campaign structural elements (CSEs) on consumer responses. The primary purpose of the study was to assess the influence of campaign structural elements on consumer intentions to purchase a cause-linked product and, secondly, their cognitive and affective attitudes toward the cause-related marketing offer. The merit and contribution of the study are furthermore warranted because the role of high-involvement products and high-priced products in CAREMs’ has received little attention in the literature whilst evidence about CRM influencing consumer purchase intention also lack integration (Zhang et al., 2020). Since both the firm and the NPO benefit from the purchase of the offer, purchase intention and attitude both serve as indicators of a future possibility to purchase the offer. As indicated earlier, the cause chosen for the purposes of executing the study is education. The study followed a communications approach and therefore focused on the campaign structural elements that are typically communicated to consumers as part of a cause-related marketing campaign. The campaign structural elements that were investigated as structural elements, were a high- involvement product (an HP laptop computer representing a high price and requiring a fair amount of prepurchase contemplation ) vs. a low-involvement product (a Pritt glue stick representing a low price and requiring little prepurchase reflection), donation recipient specificity (explicitly specified; vague), donation magnitude (high; low) and donation expression format (actual amount; percentage-of-price).

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

A cause-related marketing campaign consists of several structural elements and the specific objective to be realised with a distinctive target market in mind would usually determine the blend of these structural elements to be utilized in a particular campaign. These elements include the product featured in the campaign, the donation promised and the donation recipient. In this study we argue that the structural elements are the means or the antecedents at the disposal of a CAREM to appeal for consumers’ support and participation. The appeal consists of either convincing consumers to purchase the ‘donation’ product or ‘offer’, or to develop a positive attitude toward the product.

Outcomes studied

In this study, consumers’ purchase intention, their cognitive attitude, and their affective attitude toward the offer were tested in an experiment. Each of these variables is of importance to an NPO, as they are indicative of how effective and successful the means employed by the NPO is in its communication and appeals to their target audience. All these variables possess ‘donation-raising’ prospects, which is the goal of any CAREM. In financial terms, the importance of the outcome variables is directly related to the amount of money that is eventually earned by the CAREM for the NPO’s activities.

Purchase intention

Purchase intention refers to the possibility that a consumer plans or is willing to purchase a specific product or service sometime in the future (Wu et al., 2011). This variable has been studied widely as a predictor or precursor of subsequent purchase and extensive research has has been undertaken earlier to identify the factors that influence consumers’ purchase intention (Martins et al., 2019). Walia et al. (2016, p. 308) believe that both theoretical and empirical support provide “confirmation that consumers’ purchase intention is primarily driven by their understanding of product suitability and needs through the information provided, regardless of product type (price, complexity, and involvement).” Several scholars have also found that cause-related marketing stimulates customers’ purchase intentions, especially when the cause is relevant to their lives (Galan-Ladero et al., 2013b; Ferle et al., 2013; Webb & Mohr, 1998; Anselmsson & Johansson, 2007; Gupta &Pirsch; 2006). Chaabouni et al. (2021, p. 136) describe the behavior of consumers in respect of cause-related marketing as follows: “On the one hand, it is meant to support the cause and provide help and, on the other hand, to feel good and to experience moral satisfaction.”

In this study, purchase intention refers to the level of respondents’ intentions to purchase the Pritt glue stick or the HP laptop that featured in the print advertisement stimuli as part of a hypothetical cause-related marketing campaign.

Attitudes toward the offer

Schiffman and Wisenblit (2019, p. 172) define attitude as “a learned predisposition to behave in a consistently favorable or unfavorable way toward a given object.” In the context of the current study, attitude thus refers to consumers’ consistent favorable or unfavorable attitude toward the CAREM offer. Galan-Ladero et al. (2013a, p. 265) found that if potential donors’ attitudes are positive toward a CAREM, they are also “likely to experience higher levels of post-purchase satisfaction with the product and/or brand linked to the campaign.” A CAREM offers consumers more than only the product and its usual benefits; it also offers underlying augmented benefits of supporting a commendable cause and acting in unity with others who have also supported the cause (Chen et al., 2012; Sokolowski, 2013). After the offer has been decided upon and the donation recipient specified, it is usually communicated to potential donors. In this study, the offer was communicated to the ‘market’ through advertising. The attitude toward an advertisement could be particularly influential on the evaluation of the offer and the eventual intention of a potential donor to participate and donate to the cause of the CAREM (Briggs et al., 2010; Linden, 2011). An advertisement can influence consumer attitudes at both the cognitive and the affective level. The literature further suggests that the eventual longer-term value of a CAREM is dependent on the attitudes that consumers have about the cause, the beneficiary, and the CAREM. In the current study consumers’ cognitive and affective attitudes toward the CAREM offer were investigated. Cognitive attitude was operationalized as a consumer’s positive or negative cognitions, that is, the knowledge and perceptions of the features of a CAREM offer that the consumer acquired from direct experience with the CAREM offer and information collected from other sources (Schiffman & Wisenblit, 2019). If a potential donor expects that their actions will result in beneficial outcomes, it can be expected that their donation to an campaign will influence their intention to donate, specifically to education campaigns (Schwarzer, 1992; Oosterhof et al., 2009). In the context of the current study, affective attitude refers to consumers’ emotions and feelings regarding the CAREM offer (Schiffman & Wisenblit, 2019). Bekkers and Wiepking (2011, p. 938) assert that “the psychological benefits for the donor from giving [or purchasing the offer in this study] result almost automatically in emotional responses such as a positive mood, alleviation of feelings of guilt, reducing aversive arousal, satisfying a desire to show gratitude, or to be a morally just person.”

Structural elements

The four campaign structural elements investigated in this study, namely product involvement, donation recipient specificity, donation magnitude and donation expression format also served as the antecedents that will trigger the outcomes studied. Hypotheses were formulated in respect of the influence of the structural elements on the outcome variables as well as hypotheses to guide our investigation of the interaction effects between the structural elements.

Product involvement

The importance of the role of the product in a CAREM and its relationship with the promotion of the cause is well documented and there is general consensus that the product chosen for a CAREM has a strong influence on consumer behavior and the eventual success of the campaign (Strahilevitz, 1999; Hamiln & Wilson, 2004). The perceived fit between the product and the cause has been examined comprehensively because it plays a key role in influencing “both the credibility of the campaign and the attitude toward the brand” (Melero & Montaner, 2016, p.161). Examples of studies that investigated the relationship between cause and product type include utilitarian versus hedonic (Chang et al., 2018); cause and product category (Lafferty et al., 2016); cause and luxury versus non-luxury products (Baghi & Gabrielli, 2018); and the fit between product and the cause (Sheikh & Beise-Zee, 2011). However, research on the role of product involvement in a CAREM is scant. This study was conducted in response to calls to specifically investigate the role of product involvement and its influence on purchase intention and several other desirable CRM campaign outcomes (Robinson et al., 2012; Lucke & Heinze, 2015).

Product involvement has previously been operationalized in many ways. For instance, “a product is considered to be high involvement when it is perceived to be of high personal importance and low involvement when it is perceived to be of low personal importance” (Stewart et al., 2019, p. 2454). Product involvement also determines how advertising influences consumers and serves as an antecedent of purchase involvement (Park & Mittal, 1985). A high-involvement product would typically trigger a process that results in the collection of more information that is then used in extensive cognitive information-processing in contrast to a low-involvement product Laurent and Kapferer (1985) contend that the extent of the prepurchase effort that a consumer is willing to undertake, depends on the perceived risk or importance that a customer associates with a product. A high-involvement product is therefore associated with “a higher perceived risk, and thus [requires] a more effortful, information-driven, cognitive decision-making process than that associated with a low-involvement product” (Stewart et al., 2019, p. 2454). For this study, the level of product involvement was determined by the price of the product and the extent of decision-making required from consumers when they consider purchasing the products concerned. In this study two product involvement levels were used. A Pritt glue stick represented the low- involvement product, whilst an HP laptop was selected as representing the high-involvement alternative.

Several studies investigated the relationship between product involvement and positive outcomes such as purchase intention, cognitive attitude toward the offer, and affective attitude toward the offer. Lucke and Heinze (2015), for instance, found that the purchase intention of a CRM-linked product is strongly influenced by product involvement, whilst Nagar (2015) also observed that higher levels of product involvement led to a stronger effect on brand image. Pérez and García de los Salmones (2018) found that consumers’ perceptions of functional utilities of fair-trade products significantly and positively affect their attitudes toward and their buying intentions of fair-trade products. In brief, it can be argued that the level of product involvement has demonstrated a positive relationship with both attitude and purchase intention. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Product involvement will influence consumer intentions to purchase the cause-linked product featured in the CAREM campaign.

H2: Product involvement will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer.

H3: Product involvement will influence affective attitude toward the CAREM offer.

Donation recipient specificity

An important decision in any CAREM campaign planning is the specificity of the donation recipient associated with the campaign (Sheikh & Beise-Zee, 2011). Despite the importance of a consumer’s decision of which donation recipient to support, Nesbit et al. (2015) point out that little is known about how donors make choices among competing donation recipient organizations. Breeze (2013, p. 165) notes that the question of “which charities to support, as opposed to questions about whether to give and how much to give, has been under-researched.” Sneddon et al. (2020) report that a donor’s choice of a specific cause to support relies on the trust in a specific charity. The role of the firm’s brand has been more readily assessed, but there is still inconclusive evidence about whether specifying the NPO brand in a CAREM will impact consumer responses. Typically, two broad options are available to a donor’s recipient choice, namely donations to a vague recipient (e.g., “a donation will be made to charity”), or alternatively, to a specific donation recipient whose name will be explicitly mentioned in campaign communications (Sheikh & Beise-Zee, 2011). These two recipient options were investigated in the current study.

In the focus groups that preceded the experimental study phase, the NPO brand included in the current research, namely ‘Reach for a Dream’, emerged as a well-established NPO brand in South Africa. ‘Reach for a Dream’ encourages children of all income groups and of any ethnic origin or creed between the ages of three and 18 years to follow their dreams and fight life-threatening illnesses such as cancer and leukaemia, cystic fibrosis and muscular dystrophy, kidney failure and HIV infections. Participants were thus familiar with ‘Reach for a Dream’, attitudes toward it were positive and it was a good fit with both the products studied.

It therefore seems that firms that exercise care in their choice of which NPO to support and, where possible, endeavor to contribute money and other assistance focused on activities associated with both their business and the cause, should appeal more to donors. The discussion of the literature on donation recipient specificity has led to the formulation of the following hypotheses:

H4: Donation recipient specificity will influence consumer intentions to purchase the cause-linked product featured in the CAREM.

H5: Donation recipient specificity will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer.

H6: Donation recipient specificity will influence affective attitude toward the CAREM offer.

Donation magnitude

Donation magnitude refers to the size, amount or extent of the money or goods that a firm will contribute to a cause every time a customer buys a product or service from that firm (Chang, 2008; Folse et al., 2010). The current study investigated the effect of the magnitude of cash donations. Folse et al. (2010) emphasize the importance of customers’ perceptions of the firm in a CAREM, as they found that the positive effect of the size of the donation amount on the participation intentions of respondents was mediated in full by consumer inferences about the firm. Müller et al. (2014, p. 178) point out that earlier research on the influence of donation size on a CAREM’s success remains unclear: “Some studies find a positive effect, others a negative one, and others no effect at all.” For instance, although consumers may get an added ‘warm glow’as the donation size increases that should increase their likelihood to purchase, a larger donation amount can also result in more positive evaluations of the brand (Andreoni, 1990, p. 464). A warm glow “characterizes the moral satisfaction people feel as a result of charitable giving” (Winterich & Barone, 2011, p. 864). However, some consumers who consider a CAREM offer with a considerable donation amount would rather want to keep their money for themselves or they would deem the promised extent of the donation as too unrealistic to materialize (Müller et al., 2014). Donation size could therefore also result in an undesirable effect on sales and brand image. Chaabouni et al. (2021, p. 129) in turn, observe “that the size of the donation does not directly contribute to the purchase intention,” but that it causes scepticism when the donation is unrealistically large. This scepticism influences the warm glow alluded to earlier negatively which, in turn, influences the intention to buy a CAREM product for a nonprofit organization. Moosmayer and Fuljahn (2010) argue that a high donation amount is more valued than a smaller donation amount as the latter may indicate potential exploitation by the firm. However, where the donation is substantial, consumers may not believe that the firm will in actual fact make the promised large donation. After a series of CAREM studies, Tsiros and Irmak (2020) concluded that consumers frequently respond more positively to a relative low donation amount than to a higher donation amount, even though the cause targeted by the higher donation might be perceived as more important than an alternative cause. Against this background, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H7: Donation magnitude will influence consumer intentions to purchase the cause-linked product featured in the CAREM campaign.

H8: Donation magnitude will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer.

H9: Donation magnitude will influence affective attitude toward the CAREM offer.

Donation expression

Firms that engage in a CAREM have to make decisions about the manner in which the donation amount will be communicated in the campaign. Donation expression refers to the format in which the amount of the purchase price that the specified charity will receive is communicated to potential buyers/donors. The two most popular types of donation expression are either “a concrete amount (either a Rand amount, or a specific percentage of the price)” or “a vague/unspecified statement such as ‘a portion of the proceeds will be donated’ [to the associated charity]” (Das et al., 2016, p. 298). The framing of the donation amount has also been referred to as the ‘donation size’ and ‘donation quantifier’ (Das et al., 2016). Pracejus et al. (2003, p. 27) propose that firms should indicate their “CRM offers either in the form of a dollar value per unit, or as a percent[age] of the sales price.” Grau et al. (2007) confirmed that the most trusted and preferred donation quantifier is the exact monetary amount.

Two donation expression formats were investigated in this study, namely the actual amount and the percentage-of-price. Using these expression formats, as indicated by other researchers, will not only prevent possible confusion about the eventual amount that will go to the NPO, but they may also increase consumers’ purchase intentions. The following hypotheses were thus put forward:

H10: Donation expression will influence consumer intentions to purchase the cause-linked product featured in the CAREM campaign.

H11: Donation expression format will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer.

H12: Donation expression format will influence affective attitude toward the CAREM offer.

In this study we investigated not only the individual effects of each treatment on the outcome variables as a main effect, but also their combined effect. Further hypotheses were thus formulated to observe the interaction when the effect of one structural element variable depends on the level of another. Given their study’s findings and the impact of product involvement on CAREM outcomes, Lucke and Heinze (2015, p. 652) suggest that future studies are warranted to “decode further elements that explain purchase intention for donation-linked products.” This led to the formulation of the following hypothesis:

H13: The interaction between product involvement and donation recipient specificity will influence consumers intentions to purchase CAREM products.

Fajardo et al. (2018) point out that consumers decide first on whether they will donate – a decision that is largely influenced by the impact of the donation – and then they consider the amount to be donated. The donation amount has two elements: its magnitude (size) and how the amount is quantified. Grau et al. (2007, p. 87) found that firms should “express their donation concretely using the exact dollar amount of the donation.” Pracejus et al. (2003) support this notion, adding that a concrete donation quantifier enhances consumers’ purchase intentions. From this discussion, the following hypothesis was investigated:

H14: The interaction between donation expression format and donation magnitude will influence consumers intention to purchase CAREM products.

The influence of a product and the choice of a particular cause to support is well documented in the literature (Strahilevitz, 1999; Lafferty et al., 2016; Sheikh & Beise-Zee, 2011). Galan-Ladero et al. (2013a) found that consumers’ positive attitudes toward a credible donation recipient tend to result in higher levels of post-purchase satisfaction with the product and/or brand linked to the CAREM. The following hypothesis was thus examined:

H15: The interaction between product involvement and donation recipient specificity will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM products.

Methodology

The research design comprised initial secondary research in the form of a literature review and qualitative focus groups to explore the concept of CAREM in the South African context. The final phase of the study used experiments to empirically investigate the relationships between the structural variables of product involvement, donation recipient specificity, donation magnitude and donation expression format and the outcome variables of consumers’ purchase intention, their cognitive attitude, and their affective attitude toward the offer.

Focus groups

Qualitative research was conducted by means of consumer focus groups as phase one of the study. A phenomenological perspective was followed to understand the focus group participants’ everyday awareness, opinions and experiences pertaining to CAREM as recommended by Prendergast and Maggie (2013). Each focus group consisted of between six and ten participants. Gender and ethnicity criteria were used to randomly assign participants to one of the six groups. The focus groups also contributed to the design of the experimental stimuli to be used in the quantitative research phase. Table 1 is a summary of the focus group participation criteria and group profiles.

Table 1.

Focus group participation criteria

| Criteria | Description | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female; Male | ||||||

| Income | LSM 7–10 (Higher income groups) | ||||||

| Age | 22 years and older | ||||||

| Employment status | In full-time employment | ||||||

| Ethnic group | Black; white | ||||||

| Education | All participants completed either secondary or tertiary education | ||||||

| Focus group profiles | |||||||

| Criteria | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Group 6 | |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Income | LSM 7+ | LSM 7+ | LSM 7+ | LSM 7+ | LSM 7+ | LSM 7+ | |

| Age | 22+years | 22+years | 22+years | 22+years | 22+years | 22+years | |

| Ethnic group | White | White | Black | Black | Black | Black | |

| Employment status | In full-time employment | ||||||

| Education | All participants completed either secondary or tertiary education | ||||||

LSM = Living Standards Measure

The focus groups were conducted by an experienced moderator with the aid of a discussion guide. The moderator guided the process in a venue that was equipped with a one-way window, allowing the researchers to be present throughout the discussions without the participants noticing. The six focus group sessions each covered four phases. The first phase attended to the purpose of the session and the participants were introduced to the concept of qualitative research. The importance of information-sharing and group participation was also emphasized. Participants also introduced themselves, their occupation, hobbies, and interests. The first phase took 10 min.

During the second phase, which took 20 min, examples of cause-related marketing (CRM) advertisements were shown on a big screen to the participants. After viewing the examples, the participants discussed their initial thoughts provoked by the advertisements, their likes and dislikes of the advertisements, cause-and-product fit, and their likelihood of purchasing a product because of the campaign.

The third phase, which lasted 30 min, firstly explored participants’ understanding of the CRM concept/idea on a broad scale to assess their level of understanding of the concept. This exploration was followed by the use of examples to probe deeper as the discussion progressed. This was followed by a detailed explanation of a CRM program by the moderator. After the detailed explanation of a CRM program, participants were requested to share the factors that they as consumers deem important when they thought of a CRM program. A plethora of views and ideas emerged from the participants, such as the emotional and functional benefits associated with cause related marketing involving a third party that will benefit from the sale of the product; participants’ awareness of any companies, brands, or products that were involved with a CRM program and which ones came to mind; participants’ reaction to these programs and whether they felt any different toward companies, brands or products that were involved with CRM programs compared to those that were not; whether a CRM program changed participants’ opinions of a company if they realized that the company was donating to a relevant cause; and the impact that a CRM program had on participants’ behavior. The participants were encouraged to speak freely about the aspects that impacted them, such as the types of product, the different product categories, the different marketing related-causes and the price of the product.

The fourth phase, which lasted 60 min, required the participants to create their ideal CRM campaign. Participants were provided with the following types of products and were instructed to develop the ideal campaign relevant to each product: cleaning products; grocery items (consumables); financial products; health products; stationery; clothing and fast food. The major ideas that emerged in respect of the participants’ campaign elements were the following:

Cause versus charity – preferences toward a general cause like education as opposed to a specific charity organization.

Preference regarding the type of cause or charity – certain charity and cause combinations warrant more support.

Donation level (a high, medium, or low amount) being contributed.

Donation format – a specific amount, a percentage of the price of the product, or a percentage of the profit being donated.

The geographical extent of the cause – local, national, or international.

Co-branding between the product and the cause – the importance of the fit between brands, whether it is complementary or not complementary.

Timeframe of the campaign – long term or short term.

Transparency on the part of the charity organization – informing the consumer how their money is spent.

.

The focus groups helped to develop the quantitative research design by guiding the selection of campaign structural elements and the outcome variables for inclusion in the study and contributing to the stimuli creation process.

Experimental design

The unique strength of experimental research is its internal validity (causality) due to its ability to link cause and effect through treatment manipulation, while controlling for the spurious effect of extraneous variables (Bhattacherjee, 2021). Maturation and mortality effects were prevented as each respondent participated in the data collection only once. As the study was a post-test only design, testing effects could not compromise the validity of the empirical results, whilst potential selection effects were addressed by randomly assigning male and female, black and white subjects to individual experimental groups. Design contamination was prevented as respondents were unaware of the purpose of the experimental study and compensation rivalry amongst respondents was avoided by offering an equal, predetermined incentive for participation. As the experiment was conducted online, the possibility of social interaction amongst respondents and thus the demand effects were avoided. Instrumentation effects were prevented by collecting the data in an identical fashion for each experimental group, thereby ensuring that the only differences between questionnaires were those pertaining to the manipulations.

Manipulation checks were conducted during the pretest to ensure that the manipulations are perceived as distinctly different from one another. In essence, the manipulation checks are intended to provide evidence of construct validity (Chester & Lasko, 2021). The manipulation checks featured product involvement, donation magnitude and donation expression format. The donation recipient specificity manipulation did not require a similar manipulation check as it was simply represented by the recipient being present or absent. The attitude of respondents toward the donation recipient was evaluated prior to exposure to any stimuli to assess whether respondents held a similar attitude toward the recipient across experimental groups.

In this study, external validity was enhanced by the recruitment of non-student, income-earning respondents who had the financial ability to make donations. Furthermore, the advertising stimuli used in the study were actual rather than fictitious brands and similar to those used in actual CAREM campaigns.

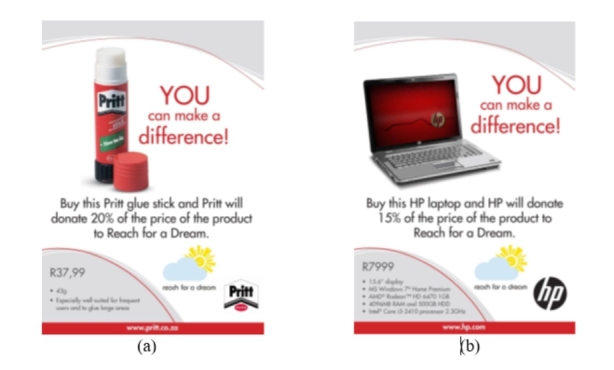

Sixteen print advertisements were prepared to fit the 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects experimental design that required a unique advertisement for each of the resultant 16 experimental groups. The print advertisements were developed in conjunction with a graphic designer to contribute to external and face validity. Figure 1 provides examples of the advertisement stimuli used. Table 2 contains a summary of the advertisements’ content and the experimental groups exposed to them.

Fig. 1.

Illustrations of the (a) low-involvement stimulus and (b) the high-involvement stimulus with the logo of ‘Reach for a Dream’

Table 2.

Experimental stimuli summary

| Experimental group and stimuli number | Donation expression format | Donation magnitude | Donation recipient specificity | Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Percentage | High (20%) | Specified recipient | Low |

| 2 | Percentage | Low (1%) | Specified recipient | Low |

| 3 | Actual amount in Rand | High (R9.50) | Specified recipient | Low |

| 4 | Actual amount in Rand | Low (R1.50) | Specified recipient | Low |

| 5 | Percentage | High (20%) | Vague recipient | Low |

| 6 | Percentage | Low (1%) | Vague recipient | Low |

| 7 | Actual amount in Rand | High (R9.50) | Vague recipient | Low |

| 8 | Actual amount in Rand | Low (R1.50) | Vague recipient | Low |

| 9 | Percentage | High (15%) | Specified recipient | High |

| 10 | Percentage | Low (1%) | Specified recipient | High |

| 11 | Actual amount in Rand | High (R750) | Specified recipient | High |

| 12 | Actual amount in Rand | Low (R65) | Specified recipient | High |

| 13 | Percentage | High (15%) | Vague recipient | High |

| 14 | Percentage | Low (1%) | Vague recipient | High |

| 15 | Actual amount in Rand | High (R750) | Vague recipient | High |

| 16 | Actual amount in Rand | Low (R65) | Vague recipient | High |

Sample

In experimental research it is recommended that at least ten to fifteen respondents or test units are included per experimental group (Field, 2012). Considering that this study comprised 16 experimental groups, the minimum number of respondents required for meaningful analysis was 480. To make provision for the possibility of an in-depth inquiry and a similar representation of males and females from white and black ethnic groups in each cell, a large number of 1 920 test units were included in the post-exposure phase of the study. Following the implementation of the screening question, the total number of respondents included in the further post-exposure analysis was 1 715. The test unit distribution and the ethnic profile per experimental group are displayed in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Respondent distribution per experimental group

| Experimental group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents per group | 108 | 88 | 88 | 112 | 110 | 103 | 111 | 105 | 109 | 100 | 109 | 116 | 115 | 114 | 115 | 112 |

| % of total sample | 6.3 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 6 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.5 |

Table 4.

Ethnic group distribution of respondents per experimental group

| Experimental group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of black respondents per group | 48.1 | 52.3 | 53.4 | 48.2 | 47.3 | 44.7 | 46.8 | 45.7 | 48.6 | 47.0 | 47.7 | 49.1 | 48.7 | 50.9 | 48.7 | 49.1 |

| % of white respondents per group | 51.9 | 47.7 | 46.6 | 51.8 | 52.7 | 55.3 | 53.2 | 54.3 | 51.4 | 53.0 | 52.3 | 50.9 | 51.3 | 49.1 | 51.3 | 50.9 |

The ethnic profile of respondents was incorporated on the basis of equal representation of black and white test units. In total, 831 black (48.5% of the total sample) and 884 white (51.5% of the total sample) respondents participated in the study. A Chi-square test was conducted to confirm that the ethnic distribution was similar across the experimental groups. No statistically significant differences were found (p = 1.000).

Male respondents made up 840 (49%) and female respondents 875 (51%) of the total sample. A Chi-square test was conducted to confirm that the gender distribution was similar across the experimental groups. No statistically significant differences were found (p = 1.000). It was thus confirmed that the gender distribution across the experimental groups was similar.

Data collection and measures

The measurement scales used in this experiment can be divided into three categories, namely demographic variables, pre-exposure and post-exposure measures. The demographic variables in respect of which data were collected, included gender, ethnic profile, age, education level and household information (household size, number of children, monthly household income and number of income earners per household).

Before exposure to the experimental stimuli, brand awareness and brand attitude were measured. The purpose was to gain a better understanding of the respondents’ awareness of and attitude toward an existing product/brand, in this case Pritt, HP, and ‘Reach for a Dream’. It was measured with a seven-point semantic differential scale consisting of three items. Table 5 summarizes the brand awareness measures used, whereas Table 6 shows the brand attitude measures used.

Table 5.

Brand awareness measures

| Measure | Awareness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale type | Seven-point semantic differential | ||

| Question posed | My awareness of the Pritt/HP/’Reach for a Dream’ brand is best described as: | ||

| Response options | |||

| Original items | Items adapted for this research | ||

| Negative option | Positive option | Positive option | Negative option |

| unfamiliar | familiar | familiar | unfamiliar |

| did not recognise | recognised | I recognise it | I do not recognise it |

| had not heard of | had heard of | I have heard of it | I have not heard of it |

Table 6.

Brand attitude measures

| Measure | Brand attitude | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale type | Seven-point semantic differential | ||

| Question posed | My attitude toward the Pritt/HP/’Reach for a Dream’ brand is: | ||

| Response options | |||

| Original items | Items adapted for this research | ||

| Negative option | Positive option | Negative option | Positive option |

| Bad | Good | Bad | Good |

| Dislike | Like | Dislike | Like |

| Unfavorable | Favorable | Unfavorable | Favorable |

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive |

Note: Adapted from the scale used by Folse et al. (2010)

To ascertain whether acceptable levels of familiarity and positive attitudes toward the relevant brands existed, the respondents were split into four groups for analysis purposes. The findings indicated a high level of familiarity and positive attitudes toward the Pritt glue stick(µ = 6.42; µ = 6.43) and ‘Reach for a Dream’ (µ = 5.30; µ = 5.97). Similar results for familiarity/positive attitudes toward the HP laptop (µ = 6.56; µ = 6.31) and ‘Reach for a Dream’ (µ = 5.23; µ = 5.93) were observed. The high µ-values obtained (the maximum possible value was 7) indicated that the familiarity and attitudes toward brands were suited for use in further analysis.

After exposure to the experimental stimuli, the purchase intention, cognitive attitude and affective attitude of participants were measured. The original scale items and the adaptations made to suit the requirements of the current study are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Purchase intention scale

| Measure | Purchase intention |

|---|---|

| Part 1 | |

| Scale type | Seven-point Likert scale anchored by strongly disagree and strongly agree |

| Original five-item scale | Items adapted for this research |

| I am eager to check out the product because of this advertisement | I am eager to check out the Pritt glue stick because of this advertisement / I am eager to check out the HP laptop because of this advertisement |

| I intend to try this product | I intend to try this Pritt glue stick / I intend to try this HP laptop |

| I plan on buying this product | I plan on buying this Pritt glue stick product / I plan on buying this HP laptop product |

| I would consider purchasing this product | I would buy the Pritt glue stick featured in the advertisement / I would buy the HP laptop featured in the advertisement |

| Part 2 | |

| Original three-item scale | Items adapted for this research |

| If I were going to buy a bicycle, the probability of buying this model is | If I were going to buy glue stick, I would probably buy the Pritt featured in the advertisement / If I were going to buy a laptop, I would probably buy the HP featured in the advertisement |

| The probability that I would consider buying this bicycle is | At the price shown, I would consider buying the glue stick featured in the advertisement /At the price shown, I would consider buying the laptop featured in the advertisement |

The cognitive attitude toward the offer (shown in Table 8) stems from the research of Ellen et al. (2000) and consists of five, seven-point semantic differential statements that are used to measure consumers’ evaluation of a CAREM offer. This construct was operationalized as the predisposition to cognitively respond in a consistently favorable or unfavorable manner toward the CAREM offer (Schiffman & Wisenblit, 2019). Table 8 summarizes the cognitive attitude of participants toward the offer. It must be noted that the semantic differential statements in this study remained the same as in the original scale, but the original question posed was changed from ‘The typical consumer would think the offer: to ‘I think the offer presented in the advertisement…’ to reflect that the question is about the respondents’ own attitudes and not about their perceptions of other consumers’ views.

Table 8.

Cognitive attitude toward the offer

| Measure | Attitude toward the offer (cognitive) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale type | Seven-point semantic differential | ||

| Question posed | I think the offer presented in the advertisement: | ||

| Response options | |||

| Original items | Items adapted for this research | ||

| Negative option | Positive option | Negative option | Positive option |

| is negative | is positive | is negative | is positive |

| is bad | is good | is bad | is good |

| is harmful | is beneficial | is harmful | is beneficial |

| is foolish | is wise | is foolish | is wise |

| will not make a difference | will make a difference | will not make a difference | will make a difference |

| is negative | is positive | is negative | is positive |

As mentioned earlier, affective attitude refers to the predisposition to affectively respond in a consistently favorable or unfavorable way toward (in this case) the CAREM offer. Table 9 portrays the particulars of the scale and items that measured the affective attitude toward the offer in this study.

Table 9.

Affective attitude toward the offer

| Measure | Attitude toward the offer (affective) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale type | Seven-point semantic differential | ||

| Question posed | When I see the offer presented in the advertisement, I feel: | ||

| Response options | |||

| Original items | Items adapted for this research | ||

| Negative option | Positive option | Negative option | Positive option |

| Sad | Delighted | Annoyed | Happy |

| Annoyed | Happy | Tense | Calm |

| Tense | Calm | Disgusted | Acceptance |

| Bored | Excited | Sorrow | Joy |

| Angry | Relaxed | ||

| Disgusted | Acceptance | ||

| Sorrow | Joy | ||

A web-based questionnaire using Qualtrics was used for online data collection. The questionnaire was accompanied by a letter that explained the purpose of the study, requesting and encouraging customers to participate in the study.

Statistical analysis techniques

A factorial experiment was selected as the most appropriate research design for this study as it enables marketers to investigate the concurrent effects of two or more structural elements on a single or multiple outcome variable(s) (Hair et al., 2008). The effectiveness of a CAREM depends largely on the structural elements that were selected for the campaign as they often exert a collective influence on consumer responses. Several statistical techniques were used to analyze the raw data. Reliability and data unidimensionality were evaluated by means of scale reliability analysis and principal axis factoring respectively. Demographic data were used to prepare cross-tabulations to provide an overview of the composition of the total sample of the study and the experimental group composition. The individual and collective influences of the structural elements on the measured outcome variables were investigated by means of a one-way and univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc tests were conducted where more information about the nature of the experimental treatments’ impact and consequent between-group differences were required.

Results

Given the number of variables investigated in this study – four main effects and five interaction effects for each of the three outcome variables (purchase intention, cognitive attitude, and affective attitude) - only statistically significant empirical findings or relationships are reported.

Purchase intention

The following section reports on the quantitative findings of the study. The objective was to assess the influence of the structural elements on the outcome variable. The data analyses by means of Univariate ANOVA revealed several statistically significant results, which are summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Main and interaction effects on purchase intention

| Tests of between-subjects effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F-value | Significance |

| Product involvement | 169.159 | 1 | 169.159 | 90.246 | 0.000*** |

| Product involvement x Donation recipient specificity | 7.327 | 1 | 7.327 | 3.909 | 0.048* |

| Donation magnitude x Donation expression format | 7.702 | 1 | 7.702 | 4.109 | 0.043* |

*** = p < 0.000; ** = p < 0.01; * = p < 0.05

As product involvement had a significant impact on consumer intention to purchase CAREM products (p = 0.000; F = 90.246), H1 was accepted. The estimated marginal means indicated that respondents favored the low-involvement scenario (µ = 5.325) above the high-involvement scenario (µ = 4.695). The low-involvement Pritt glue stick featured in the CAREM advertisement thus resulted in more positive purchase intentions than the high-involvement HP laptop. There is evidence of significant two-way interactions between: (1) product involvement and donation recipient specificity, and (2) between donation magnitude and donation expression format. H13 and H14 could therefore be accepted at the p < 0.05 level of significance.

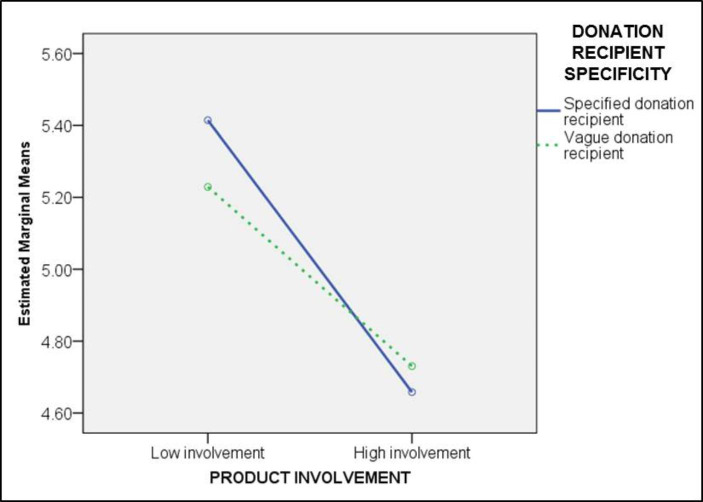

The two-way interaction between product involvement and donation recipient specificity that exerted a significant influence on purchase intention (F = 3.909; p = 0.048) is graphically illustrated in Fig. 2. This result provides support for H13. The highest purchase intention scores were generated by exposure to the CAREM stimulus featuring a specified beneficiary and a low-involvement product (µ = 5.421). It can thus be inferred that consumers prefer supporting a CAREM where the offer requires a low-involvement product and certainty that their donation will go to a specific nonprofit organization. The lowest purchase intention score (µ = 4.729) resulted from exposure to a high involvement product scenario featuring a donation promise to a specified beneficiary.

Fig. 2.

Interactive influence on purchase intention caused by product involvement and donation recipient specificity

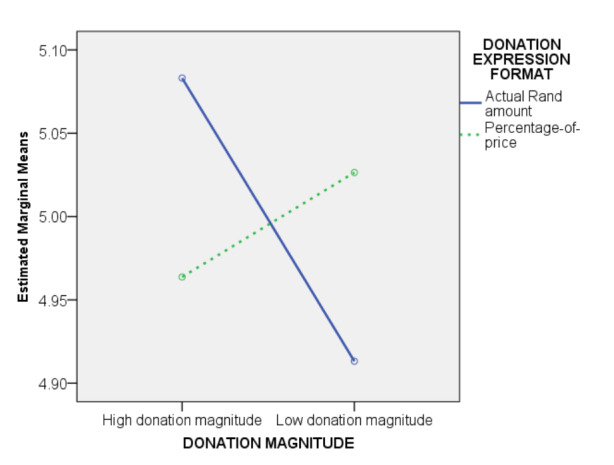

The interaction between donation magnitude and donation expression format, as indicated in Table 10, was significant in influencing purchase intention at the p < 0.05 level (F = 4.109; p = 0.043) and provides support for H14. Figure 3 provides a graphical illustration of the interaction between donation magnitude and donation expression format. The most positive purchase intention score (µ = 5.111) resulted from exposure to an advertisement with a high donation magnitude, expressed as an actual amount. The actual amount expression in interaction with a low donation magnitude also resulted in the least positive purchase intention score (µ = 5.043). Figure 3 indicates that an actual amount expression generated higher purchase intentions when featured in conjunction with a high donation magnitude, but a percentage-of-price expression generated more positive purchase intentions when coupled with a low donation magnitude. From Fig. 3 it is clear that responses were more extreme when the actual amount was featured compared to the percentage-of-price scenario.

Fig. 3.

Interactive influence on purchase intention caused by donation expression format and donation magnitude

Cognitive attitude

The following sections focus on the quantitative findings of the study. The objective was to assess the influence of the structural elements and the interaction between these structural elements on the outcome variable of cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer. The data analyses by means of Univariate ANOVA revealed several statistically significant results that are summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

Main and interaction effects on cognitive attitude

| Tests of between-subjects effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F-value | Significance | |

| Product involvement | 21.366 | 1 | 21.366 | 15.748 | 0.000*** | |

| Donation recipient specificity | 8.521 | 1 | 8.521 | 6.280 | 0.012* | |

| Product involvement * Donation recipient specificity | 3.750 | 1 | 3.750 | 2.764 | 0.097# | |

*** = p < 0.000; ** = p < 0.01; * = p < 0.05; # = p < 0.10

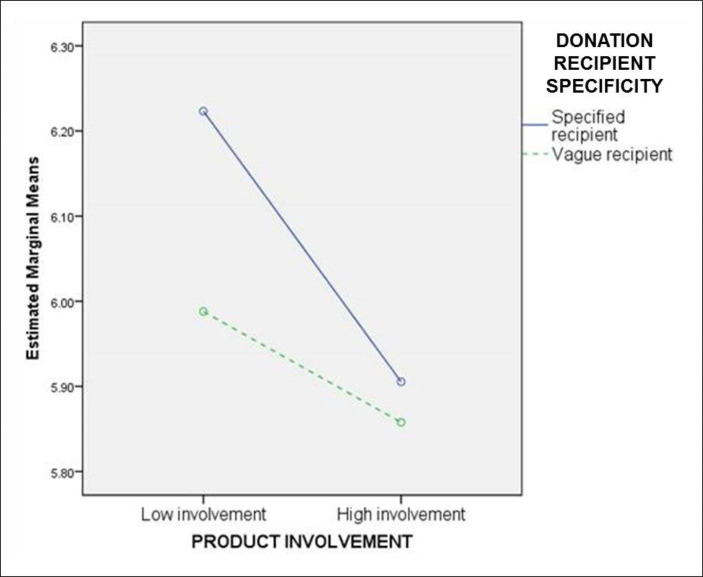

Product involvement and donation recipient specificity, as individual main effects, significantly impacted cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer. Product involvement, as a main effect, exerted a significant influence on the respondents’ cognitive attitudes toward the CAREM offer (F = 15.748; p = 0.000). H2 was thus accepted at the p < 0.000 level. According to the estimated marginal means, the low-involvement product produced a more positive cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer as presented in the CAREM advertisement (µ = 6.106) than the high-involvement product (µ = 5.882). The product involvement impact was thus similar to the findings for the other outcome variable, namely purchase intention. Donation recipient specificity, as a main effect, also exerted a significant impact on cognitive attitude toward the offer (F = 6.280; p = 0.012). H5 was thus accepted at the p < 0.05 level. The presence of a specified donation recipient in the CAREM campaign prompted more positive cognitive attitudes toward the offer (µ = 6.064) than the presence of a vague beneficiary (µ = 5.923).

Evidence of a significant two-way interaction between product involvement and donation recipient specificity was found at the p < 0.10 level of significance. H14 was thus accepted at the p < 0.10 level. Figure 4 graphically illustrates this finding.

Fig. 4.

Interactive influence on cognitive attitude caused by product involvement and donation recipient specificity

It is evident from Fig. 4 that cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer was more positive in the low-involvement scenario, both when respondents were presented with a specified and a vague donation recipient. Figure 4 also illustrates that cognitive attitudes were more positive when respondents were exposed to a specified donation recipient than when a vague recipient was shown, regardless of the product involvement featured in the advertisement. Figure 4 further shows that the difference in cognitive attitude between a low- and a high-involvement scenario was more apparent when a specified donation recipient featured. The cognitive attitudes of respondents were visibly more positive when they were presented with a specified donation recipient rather than a vague recipient in the low-involvement scenario. This finding was also evident in the high-involvement scenario.

Affective attitude

This section reports on the quantitative findings of the study. The objective was to assess the influence of the structural elements and the interaction between these structural elements on the outcome variable of affective attitude to purchase a CAREM offer. The data analyses by means of Univariate ANOVA revealed several statistically significant results that are summarized in Table 12. Table 12 also reveals that in respect of affective attitude toward the CAREM offer only two main effects emerged as statistically significant.

Table 12.

Main effects on affective attitude

| Tests of between-subjects effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean square | F-value | Significance |

| Product involvement | 27.628 | 1 | 27.628 | 21.156 | 0.000*** |

| Donation recipient specificity | 4.117 | 1 | 4.117 | 3.153 | 0.076# |

*** = p < 0.000; ** = p < 0.01; * = p < 0.05; # = p < 0.10

Product involvement had a significant impact on affective attitude toward the offer (F = 21.156; p = 0.000), resulting in the acceptance of H2 at the p < 0.000 level. A more positive affective attitude toward the CAREM offer was generated in the low-involvement scenario (µ = 5.813) than in the high-involvement scenario (µ = 5.558). The product-involvement impact was similar to the findings for the outcome variables of purchase intention and cognitive attitude toward the offer. Donation recipient specificity also influenced affective attitude toward the CAREM offer (F = 3.153; p = 0.076), resulting in the acceptance of H6 at the p < 0.10 level. A more positive affective attitude toward the CAREM offer was emerged when a specified donation recipient featured in the advertisement (µ = 5.73) than when a vague donation recipient was shown (µ = 5.64).

Summary of the hypotheses accepted

Table 13 is a summary of the hypotheses accepted.

Table 13.

Summary of hypotheses accepted

| Hypothesis number | Hypothesis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Product involvement will influence consumer intentions to purchase the cause-linked product featured in the CAREM campaign | Accepted |

| H2 | Product involvement will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer | Accepted |

| H3 | Product involvement will influence affective attitude towards the CAREM offer | Accepted |

| H5 | Donation recipient specificity will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM offer | Accepted |

| H13 | The interaction between product involvement and donation recipient specificity will influence consumer intention to purchase CAREM products | Accepted |

| H14 | The interaction between donation expression format and donation magnitude will influence consumer intention to purchase CAREM product | Accepted |

| H6 | Donation recipient specificity will influence affective attitude toward the CAREM offer | Accepted at the 10% level of significance |

| H15 | The interaction between product involvement and donation recipients’ specificity will influence cognitive attitude toward the CAREM products | Accepted at the 10% level of significance |

Discussion and conclusions

Several conclusions can be drawn from the findings of the study. In all the instances where the influence of product involvement was investigated, its impact on the CAREM offer was positive. In the absence of CAREM studies published on the relationship between low and high-involvement products as antecedents and purchase intention as the outcome, it was not possible to compare product involvement findings with extant research. We regard this finding as a meaningful contribution of our research. Our findings are, however, consistent with reported research studies that found that low-involvement products tend to have a strong relationship with purchase intention. It is thus reasonable to conclude that consumers seem to commit easier to lower costs and lower risks and will therefore be more likely to respond more positively when a low-involvement product is featured in a cause-related marketing campaign.

To our knowledge our study is the first to distinguish between a cognitive and an affective attitude toward a CAREM offer. It is especially the role of product involvement, on its own or in interaction with donation recipient, that influenced affective and cognitive attitudes towards the CAREM offer. Previous findings concerning donation magnitude and donation expression format were found to be inconclusive, although some researchers suggested that the influence exerted by these CSEs often occur in interaction with other structural elements. We found that the most appropriate combination of CSEs involved in this study to be an actual amount donation expression and a donation size ranging from medium to high magnitude when combined with a specified donation recipient.

The expectation that an interaction between experimental main effects does influence consumer intention to purchase CAREM products was confirmed by significant two-way interactions between: (1) product involvement and donation recipient specificity, and (2) between donation expression format and donation magnitude. The actual amount expression generated more positive purchase intentions when featured in conjunction with a high donation magnitude, but a percentage-of-price expression generated more positive purchase intentions when coupled with a low donation magnitude. The results of this study suggest that the product included in a CAREM is particularly important to stimulate purchase intention and, hopefully, sales. The donation recipient plays an instrumental role in generating positive perceived firm motives and a positive attitude toward the alliance portrayed in the CAREM offer. Our findings regarding the importance of the donation recipient brand in a CAREM campaign, is in line with the findings in earlier research.

In conclusion it is appropriate to state that earlier CAREM research has yielded different findings within different cultural contexts and such differences have been reflected in consumer intentions and attitudes in particular. We therefore regard the overall findings of our study as consistent with earlier findings in respect of particular cultural settings.

Implications for marketing theory

Very few empirical studies have been undertaken on cause-related marketing in South Africa. The current study contributes to this dearth of knowledge in several ways. Firstly, the research was conducted in South Africa and the findings can therefore contribute to the context of a multicultural environment for cross-cultural comparisons in CAREM research. Secondly, the study investigated the influence of four structural elements simultaneously and therefore provides a more comprehensive view on the interactive influence of CSEs than most previous studies. Thirdly, the study was based on a communications approach and focused on the CSEs that are typically presented to consumers during CAREMs. Fourthly, the study adopted a product involvement and a cobranding-inspired framework to assess the product CSE in CAREM instead of the widely published combinations of hedonic vs. utilitarian, luxury vs. nonluxury, high-context vs. low-context culture, and other frameworks. The product involvement classification showed that low-involvement products result in more favorable consumer responses toward CAREM than high-involvement products. The fifth contribution is the insights gained from partnering a product with a specified, branded NPO that offers an effective CAREM. Baghi and Gabrielli (2018) compellingly illustrate that the majority of CAREM studies focus on investigating the forprofit partner, despite the understandable importance of the nonprofit partner. This study’s contribution is especially relevant in a context such as South Africa where NPOs are in dire need of funding. The clear message for NPOs is thus to develop a distinct brand identity with an unmistakeable focus and to devote themselves to continuously build and strengthen their brand. The study also concluded that NPOs should embrace their role as the ‘conscience of society’, that they should believe in their own knowledge and experience and enter into CAREM negotiations with firms from a position of equivalence. The sixth and final contribution arises from the outcome variables selected for the study. The research design allowed for the assessment of campaign-specific responses and was the first to distinguish between a cognitive and an affective attitude toward a CAREM offer. This distinction contributed to the limited emotion-related results available in respect of a CAREM, but also confirmed that a CAREM should not only be approached as a prosocial strategy with the purpose of affecting consumer emotions, but also as a business strategy that offers measurable returns.

Managerial implications

Product involvement played an important role in the relationship with the outcome variables that were investigated in this study. Across the experimental groups, the low-involvement product consistently resulted in more positive responses than the high-involvement product. It is therefore recommended that marketers include products in their CAREM campaigns that are well known and affordable to the target market, have a low risk and a high level of sales potential and hold positive associations for positive transfer of affect during the campaigns. Products that feature these factors are likely to appeal to the target audience.

The magnitude of the donation acceptable to consumers remains an unresolved issue. The only possible guidance emerging from this study seems that firms promising a high rather than a low donation magnitude in their CAREM campaigns are more likely to be attractive to consumers.

It is advisable that firms select the most transparent donation expression format possible when developing their CAREM campaigns, namely the actual amount expression format, thereby avoiding uncertainty or confusion. Positive framing refrains from guilt-based appeals as consumers in South Africa are inclined to respond negatively to such communication. The inclusion of positive visual imagery in their CAREM campaigns is recommended as it will encourage a positive attitude towards the campaign. An example of such imagery is a joyous visual portrayal of the beneficiaries of the CAREM campaign. Feedback to participants about the contribution raised by means of the CAREM campaign should be communicated as widely as possible. Such information will contribute positively to the consumers’ feelings of a ‘warm glow’, their social identity and to their future giving or CAREM participation. The feedback can be provided by the firm or by the non-profit organization as a message of gratitude.

To summarize, the most appropriate combination of CSEs of this study was found to be a combination of a specified donation recipient, an actual amount donation expression, and a donation size ranging from medium to high magnitude.

Limitations of the study

The most important limitation of the current study is its generalizability. Although the sample was reasonably representative of the middle- to high income segment of the population, the generalizability is limited. As far as the methodology is concerned, one has to acknowledge that exposure to a single experimental stimulus can limit the extent of perceptions elicited and affected participants’ reactions to the stimulus. A further limitation is that only a monetary transaction based CAREM was assessed and non-monetary CAREM options were not considered.

Suggestions for future research

It is suggested that in future research endeavors consumers should be given the opportunity to select a donation recipient of their choice. This suggestion is in line with that of Robinson et al. (2012) who found that consumers are likely to take part in a CAREM and that their purchase intentions tend to increase, especially if they are part of a collectivistic culture and when the cause–brand fit is low. Although the findings of this study confirmed the importance of the inclusion of a specified donation recipient in a CAREM, future studies could be extended to include a non-monetary element together with a monetary element for purposes of comparison. Furthermore, the visual portrayal of the donation recipient could be combined with visual depictions of the donation recipient or its beneficiaries and its activities. This combination could result in greater emotional appeal than merely mentioning the donation recipient’s name or showing its logo.

Declarations

Disclosure

statement: Funding and/or Conflicts of interests/Competing interests.

The authors declare that the article is their own work and no direct or indirect conflicts of interest relating to the research, authorship, funding or publication of this article exist.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/18/2023

Incorrect running author.

Contributor Information

Nic S Terblanche, Email: nst@sun.ac.za.

Christo Boshoff, Email: cboshoff@sun.ac.za.

Debbie Human-Van Eck, Email: dhuman@sun.ac.za.

References

- Achrol RS, Kotler P. Frontiers of the marketing paradigm in the third millennium. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2012;40(1):35–52. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0255-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J. Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal. 1990;100(401):464–477. doi: 10.2307/2234133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmsson J, Johansson U. Corporate social responsibility and the positioning of grocery brands: An exploratory study of retailer and manufacturer brands at point of purchase. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2007;35(10):835–856. doi: 10.1108/09590550710820702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baghi I, Gabrielli V. Brand prominence in cause-related marketing: Luxury versus non-luxury. Journal of Product & Brand Management. 2018;27(6):716–731. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-07-2017-1512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers R, Wiepking P. A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2011;40(5):924–973. doi: 10.1177/0899764010380927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2021). Experimental research from research methods for the social sciences. An open educational resource (Chap. 10). Available at https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-research-methods/.Social sciences research: Principles, methods, and practices. University of South Florida.: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/oa_textbooks/3/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Breeze B. How donors choose charities: The role of personal taste and experiences in giving decisions. Voluntary Sector Review. 2013;4(2):165–183. doi: 10.1332/204080513X667792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs E, Peterson M, Gregory G. Toward a better understanding of volunteering for nonprofit organizations: Explaining volunteers’ pro-social attitudes. Journal of Macromarketing. 2010;30(1):61–76. doi: 10.1177/0276146709352220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capella ML, Hill RP, Rapp JM, Kees J. The impact of violence against women in advertisements. Journal of Advertising. 2010;39(4):37–52. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367390403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaabouni, A., Jridi, K., & Bakini, F. (2021). Cause-related marketing: Scepticism and warm glow as impacts of donation size on purchase intention. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 18(1), 129–150 (2021). https://doi-org.ez.sun.ac.za/10.1007/s12208-020-00262-3

- Chang CT. To donate or not to donate? Product characteristics and framing effects of cause-related marketing on consumer purchase behaviour. Psychology & Marketing. 2008;25(12):1089–1110. doi: 10.1002/mar.20255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CT, Chen PC, Chu XYM, Kung T, Huang YF. Is cash always king? Bundling product–cause fit and product type in cause-related marketing. Psychology & Marketing. 2018;35(12):990–1009. doi: 10.1002/mar.21151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Szolnoki A, Perc M. Risk-driven migration and the collective-risk social dilemma. Physical Review E. 2012;86(3):1–8. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.036101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester DS, Lasko EN. Construct validation of experimental manipulations in social psychology: Current practices and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2021;16(2):377–395. doi: 10.1177/1745691620950684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crites SL, Fabrigar LR, Petty RE. Measuring the affective and cognitive properties of attitudes: Conceptual and methodological issues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20(6):619–634. doi: 10.1177/0146167294206001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das N, Guha A, Biswas A, Krishnan B. How product-cause fit and donation quantifier interact in cause-related marketing (CRM) settings: Evidence of the cue congruency effect. Marketing Letters. 2016;27(2):295–308. doi: 10.1007/s11002-014-9338-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds WB, Monroe KB, Grewal D. Effects of price, brand and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research. 1991;28(3):307–319. doi: 10.2307/3172866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen PS, Mohr LA, Webb DJ. Charitable programs and the retailer: Do they mix? Journal of Retailing. 2000;76(3):393–406. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00032-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo TM, Townsend C, Bolander W. Toward an optimal donation solicitation: Evidence from the field of the differential influence of donor-related and organization-related information on donation choice and amount. Journal of Marketing. 2018;82(2):142–152. doi: 10.1509/jm.15.0511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferle C, Kuber G, Edwards SM. Factors impacting responses to cause-related marketing in India and the United States: Novelty, altruistic motives, and company origin. Journal of Business Research. 2013;66(3):364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. (2012). Discovering statistics: Experimental project. [Online]. Available: http://www.discoveringstatistics.com/docs/project1.pdf. [2020, August 11]

- Folse JAG, Niedrich RW, Grau SL. Cause-related marketing: The effects of purchase quantity and firm donation amount on consumer inferences and participation intentions. Journal of Retailing. 2010;86(4):295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2010.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galan-Ladero M, Galera-Casquet C, Wymer W. Attitudes towards cause-related marketing: determinants of satisfaction and loyalty. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing. 2013;10(3):253–269. doi: 10.1007/s12208-013-0103-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galan-Ladero MM, Galera-Casquet C, Valero-Amaro V, Barroso-Mendez JM. Does the product type influence on attitudes toward cause-related marketing? Economics & Sociology. 2013;6(1):60–71. doi: 10.14254/2071-789X.2013/6-1/5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grau LG, Garretson JA, Pirsch J. Cause-related marketing: An exploratory study of campaign donation structures issues. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing. 2007;18(2):69–91. doi: 10.1300/J054v18n02_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal D, Krishnan R, Baker J, Borin N. The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers’ evaluations and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing. 1998;74(3):331–352. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(99)80099-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal D, Monroe KB, Krishnan R. The effects of price-comparison advertising on buyers’ perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions. Journal of Marketing. 1998;62(2):46–59. doi: 10.1177/002224299806200204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Pirsch J. The company-cause customer fit decision in cause-related marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2006;23(6):314–326. doi: 10.1108/07363760610701850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Bush RB, Ortinau DJ. Marketing research. New York, NJ: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hamiln RP, Wilson T. The impact of cause branding on consumer reactions to products: Does product/cause ‘fit’ really matter? Journal of Marketing Management. 2004;20(7/8):663–681. doi: 10.1362/0267257041838746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howie KM, Yang L, Vitell SJ, Bush V, Vorhies D. Consumer participation in cause-related marketing: An examination of effort demands and defensive denial. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;147(3):679–692. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2961-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IEG Sponsorship Report (2018, 8 January). Signs point to healthy sponsorship spending in 2018. Retrieved from http://www.sponsorship.com/Report/2018/01/08/Signs-Point-To-Healthy-Sponsorship-Spending-In-201.aspx

- Lafferty BA, Goldsmith RE. Cause-brand alliances: Does the cause help the brand or does the brand help the cause? Journal of Business Research. 2005;58(4):423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty BA, Lueth AK, McCafferty R. An evolutionary process model of cause-related marketing and systematic review of the empirical literature. Psychology & Marketing. 2016;33(11):951–970. doi: 10.1002/mar.20930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent G, Kapferer JN. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. Journal of Marketing Research. 1985;22(1):41–53. doi: 10.1177/002224378502200104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NR, Kotler P. Social marketing: Changing behaviors. for good. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Linden S. Charitable intent: A moral or social construct? A revised theory of planned behavior model. Current Psychology. 2011;30:355–374. doi: 10.1007/s12144-011-9122-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucke S, Heinze J. The role of choice in cause-related marketing – Investigating the underlying mechanisms of cause and product involvement. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015;213:647–653. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins J, Costa C, Oliveira T, Gonçalves R, Branco F. How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. Journal of Business Research. 2019;94(January):378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melero I, Montaner T. Cause-related marketing: An experimental study about how the product type and the perceived fit may influence the consumer response. European Journal of Management and Business Economics. 2016;25(3):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.redeen.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendinia M, Peter PC, Gibbert M. The dual-process model of similarity in cause-related marketing: How taxonomic versus thematic partnerships reduce scepticism and increase purchase willingness. Journal of Business Research. 2018;91:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmayer DC, Fuljahn A. Consumer perceptions of cause-related marketing campaigns. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2010;27(6):543–549. doi: 10.1108/07363761011078280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]