Abstract

Killing rates of fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, and vancomycin were compared against Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus aureus, pneumococci, streptococci, and Enterococcus faecalis. The times required for fluoroquinolones to decrease viability by 3 log10 were 1.5 h for Enterobacteriaceae, 4 to 6 h for staphylococci, and ≥6 h for streptococci and enterococci. Thus, the rate of killing by fluoroquinolones is organism group dependent; overall, they killed more rapidly than β-lactams and vancomycin.

The ability of an antibiotic to kill bacteria may be important in some clinical settings, such as the management of bacterial endocarditis or the treatment of bacteremia in granulocytopenic patients. Members of the primary antimicrobial classes showing bactericidal properties that are used therapeutically as single agents are the quinolones and the cell wall-active agents, specifically β-lactams and the glycopeptide vancomycin.

Quinolones exhibit concentration-dependent killing kinetics, with maximum killing rates achieved at the optimum bactericidal concentration (12), which for more recently developed fluoroquinolones occurs close to eight times their MICs (E. Gradelski, B. Kolek, D. Bonner, and J. Fung-Tomc, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. E-182, 1998). On the other hand, β-lactam antibiotics and vancomycin exhibit time-dependent kinetics (8), with little difference in killing rates at concentrations above their MICs.

In this study, we compared the killing rates of three fluoroquinolones (trovafloxacin, levofloxacin, and gatifloxacin) to those of cell wall-active agents commonly used in the treatment of infections involving specific bacterial species.

Bacterial strains used in this study were clinical isolates: four members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, four Staphylococcus aureus isolates (two methicillin susceptible and two methicillin resistant), four streptococci (two alpha-hemolytic and two beta-hemolytic streptococci), nine Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates (with various penicillin susceptibilities), and five Enterococcus faecalis isolates. The strains were chosen because their quinolone MICs were close to the respective quinolone-bacterial species modal MICs.

Gatifloxacin was from Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co. (Tochigi, Japan), methicillin was from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (Wallingford, Conn.), trovafloxacin was from Pfizer Inc. (New York, N.Y.), and levofloxacin was from the R. W. Johnson Pharmaceutical Research Institute (Raritan, N.J.). Ceftriaxone was supplied by Roche Pharmaceuticals (Nutley, N.J.), cefotaxime was supplied by Hoechst Marion Roussel (Kansas City, Mo.), and vancomycin was supplied by Eli Lilly & Co. (Indianapolis, Ind.). Penicillin G, amoxicillin, and ampicillin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.).

MICs were determined by the agar dilution method with Mueller-Hinton agar (supplemented with 5% sheep blood for pneumococci) according to standardized methods (13). The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that inhibited all visible growth.

Time-kill kinetics were conducted at drug concentrations equal to 10 times the MIC of that drug for a bacterial strain. The optimal bactericidal concentrations of quinolones are close to eight times their MICs. The maximum killing rates of seven β-lactams and vancomycin for seven strains used in this study were determined (data not shown); maximum killing occurred at four to eight times the MIC of a drug, and this rate was maintained up to 16 times the MIC. The tests were performed in Mueller-Hinton broth (staphylococci, Escherichia coli, and E. faecalis) which, for S. pneumoniae and viridans streptococcal strains, was supplemented with 7% lysed horse blood. The beta-hemolytic streptococcal time-kill studies were done in brain heart infusion broth, a medium yielding better growth of these organisms. Twenty-milliliter cultures, grown in 50-ml glass flasks, were incubated at 35°C with shaking. Cells were grown to logarithmic phase with 1 h of preincubation in fresh broth prior to the addition of drug. The starting bacterial density was approximately 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 CFU/ml. Viable counts were determined at 0, 2, 4, 6, and (except for pneumococci) 24 h after drug addition by plating known dilutions of the samples onto Mueller-Hinton agar (or for streptococci, Trypticase agar plus 5% sheep blood). The cell count plates were incubated for up to 48 h before any were considered to have no growth. With a number of strains, the cell counts were simultaneously determined with the agar plates described above supplemented with 1% magnesium chloride (M. Wooton, K. E. Bowker, H. A. Holt, and A. P. MacGowan, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. A-32, 1998), a condition known to diminish the effect of any quinolone carryover. In all cases, the bacterial cell counts for these strains were the same on both plating media. Also, plating of the culture immediately after the addition of quinolone resulted in the same cell count as that of the culture plated immediately prior to the addition of drug.

Results and discussion.

MICs and the rates of killing nonstreptococcal species are listed in Table 1. Fluoroquinolone MICs for the Enterobacteriaceae and staphylococci were ≤0.13 and ≤0.25 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Killing rates of nonstreptococcal species by quinolones and comparison compounds

| Bacterial strain and compound (no. of strains tested) | MIC (μg/ml)a | Time (h) for 3 log10 killinga |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli (2 strains) | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.016 | 0.6, 1 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.008, 0.016 | 0.9, 1.2 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.03 | 1.2 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.13 | ≥6b |

| E. cloacae A20650 | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.06 | 1.3 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.13 | 1.3 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.03 | 5.1 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.03 | >24b |

| K. pneumoniae A27464 | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.03 | 1.2 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.13 | 1.2 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.06 | 1.5 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.03 | 6 |

| MRSA A27218 | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.13 | 4 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.016 | 4 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 6 |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 24 |

| MRSA A27217 | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.13 | 1 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.016 | 3 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 3 |

| Vancomycin | 4 | >6 |

| MSSA (2 strains) | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.06, 0.13 | 1.7, 2 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.03, 0.06 | 1.5, 2 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 2 |

| Methicillin (1) | 4 | 4–6 |

| Cefotaxime (1) | 4 | 4 |

More than one value represents results for each of two strains tested.

>6 h, 3 log10 killing was achieved between 6 and 24 h of drug exposure; >24 h, 3 log10 killing was not achieved by 24 h.

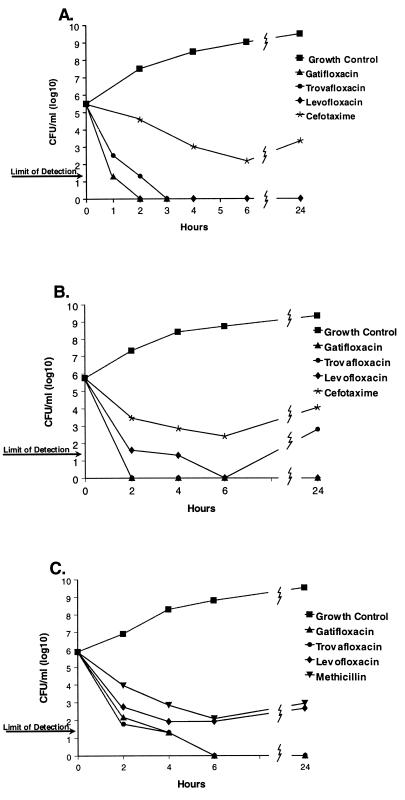

Since a 3 log10 drop in viability is considered an index of bactericidal activity (14), the time required to achieve this level of killing was determined from time-kill curves. There were minor differences among the fluoroquinolones in their rates of killing. They tended to kill Enterobacteriaceae (i.e., E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae) very rapidly, achieving a 3 log10 decrease by 1.5 h (Table 1). In comparison, the fluoroquinolones killed staphylococci more slowly, with 3 log10 killing by 4 to 6 h of exposure. Three of the four staphylococcal strains, exposed to gatifloxacin, showed a 3 log10 decrease in viability by 2 h. The differential killing rates of the Enterobacteriaceae and S. aureus by fluoroquinolones are displayed in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Time-kill curves for nonstreptococcal species: E. coli A20697 (A), K. pneumoniae A27464 (B), and MSSA A9606 (C).

Others have reported the more rapid killing of gram-negative bacteria by quinolones. Pefloxacin was more rapidly bactericidal against gram-negative strains in the first hour of contact, but the rates of killing of gram-negative and gram-positive strains were similar by 4 h of incubation (3). Likewise, PD 131628 was more bactericidal against E. coli than against staphylococci (9).

The cell wall-active agents were less rapidly bactericidal than the fluoroquinolones. To attain a 3 log10 drop in viability against Enterobacteriaceae strains, 6 to >24 h of exposure to cefotaxime was needed (Table 1). Regrowth was noted in three of the cefotaxime-treated Enterobacteriaceae cultures by 24 h of incubation, but heavy regrowth with E. cloacae A20650 was observed. Although the reason for the regrowth was not explored, with E. cloacae A20650, cefotaxime-resistant variants (i.e., cefotaxime MICs of >16 μg/ml) accounted for the heavy regrowth. Some extended-spectrum cephalosporins can readily select for resistant variants of E. cloacae (6). Methicillin and cefotaxime killed methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strains A9606 and A15090 more slowly (4 to 6 h for 3 log10 killing), as did vancomycin against the methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains (>6 to 24 h for 3 log10 killing). Thus, fluoroquinolones were more rapidly bactericidal than cefotaxime against MSSA and Enterobacteriaceae, more rapid than methicillin against MSSA, and more rapid than vancomycin against MRSA strains.

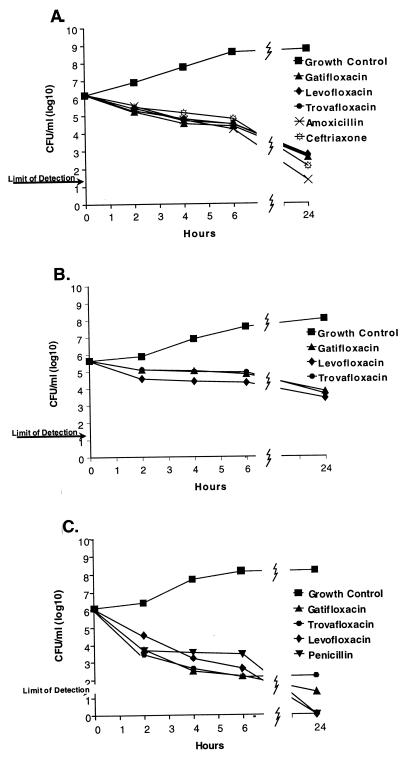

Compared to nonstreptococcal species, fluoroquinolones were less rapidly lethal against the 13 streptococcal and 5 enterococcal strains. Both fluoroquinolones and cell wall-active agents required >6 to >24 h to reduce viability by 3 log10. On the whole, all of the drugs tested killed streptococci and enterococci more slowly than the nonstreptococcal strains (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Time-kill curves for streptococci and related species: penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae A9585 (A), S. mitis A28590 (B), and S. pyogenes A20789 (C).

The data in this study on quinolone killing of streptococci are more extensive than, but confirmatory of, previous reports (Table 2). Moxifloxacin was reported to be most rapidly bactericidal for S. aureus and E. coli and least bactericidal for Streptococcus pyogenes (1, 15). Trovafloxacin was bactericidal against MRSA strains but killed Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus sanguis much more slowly (5). A low rate of enterococcal killing had been reported for ciprofloxacin (10, 12), DU-6859a (i.e., sitafloxacin) (12), trovafloxacin (11, 15), DR-3355 (10), and PD 131628 (9).

TABLE 2.

Killing rates of streptococci and related species by quinolones and comparison compounds

| Bacterial strain and compound (no. of strains tested) | MIC (μg/ml) | Time (h) for 3 log10 killing |

|---|---|---|

| S. pyogenes A20789 | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25 | 3.5 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.13 | 3 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 6 |

| Penicillin | 0.007 | >6a |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5 | 6 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.25 | >6 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | >6 |

| S. mitis | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5 | >24b |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.13 | >24 |

| Levofloxacin | 2 | >24 |

| Ampicillin | 0.008 | >6 |

| S. sanguis | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5 | >24 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.13 | >24 |

| Levofloxacin | 2 | >24 |

| Ampicillin | 1 | >24 |

| S. pneumoniae (Pen-R)c A28275 | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5 | >6 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.06 | >6 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | >6 |

| Amoxicillin | 2 | >6 |

| Ceftriaxone | 1 | >6 |

| S. pneumoniae (Pen-S)c A9585 | ||

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5 | >6 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.13 | >6 |

| Levofloxacin | 2 | >6 |

| Amoxicillin | 0.008 | >6 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.015 | >6 |

| S. pneumoniae (7 strains) | ||

| Gatifloxacin (7) | 0.5 | ≥6 |

| Trovafloxacin (1) | 0.06 | >6 |

| E. faecalis (5 strains) | ||

| Gatifloxacin (5) | 0.5–1 | 3–≥6 |

| Trovafloxacin (2) | 0.25–0.5 | 4 |

| Levofloxacin (2) | 1 | >6 |

| Vancomycin (2) | 2 | 3–3.5 |

| Ampicillin (1) | 1 | >24 |

For nonpneumococcal strains, >6 h means that 3 log10 killing was achieved between 6 and 24 h of drug exposure. For pneumococci, >6 h means that this level of killing was not attained by 6 h, the duration of the pneumococcal time-kill study.

>24 h means that 3 log10 killing was not achieved by 24 h, the duration of the time-kill study.

Pen-R, penicillin resistant; Pen-S, penicillin susceptible.

A comparison of killing rates by ampicillin and moxifloxacin of E. faecalis (F. Maggiolo, R. Capra, P. Bottura, M. Moroni, G. Pravettoni, and F. Suter, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. E-201, 1998), by ceftriaxone and sparfloxacin of viridans streptococci (4), and by penicillin and temafloxacin of Streptococcus adjacens (2) suggests that the β-lactams may kill streptococci and enterococci even more slowly than do quinolones. Recently, Hoellman et al. (7) reported the killing rates of 12 pneumococcal strains by fluoroquinolones and β-lactams; at eight times the MICs of the drugs, five to eight strains showed 3 log10 killing at 6 h by ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin; five to six strains showed killing at 6 h by amoxicillin, cefuroxime, and ceftriaxone. For all 12 pneumococcal strains to show a 3 log10 decrease in cell counts, the quinolones required 12 h of contact, while the β-lactams needed 24 h for an equal effect (7).

In summary, these results indicate that the rate of killing by fluoroquinolones is bacterial group dependent. Fluoroquinolones kill gram-negative bacteria more rapidly than staphylococci. Quinolones killed nonstreptococcal strains more rapidly than did β-lactams and vancomycin. Although fluoroquinolones kill streptococci and enterococci more slowly, these rates may be similar to, and possibly higher than, those achieved by the β-lactams and vancomycin. Overall, against a spectrum of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, the quinolones exhibit the more favorable bactericidal profile.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boswell F J, Andrews J M, Wise R, Dalhoff A. Bactericidal properties of moxifloxacin and post-antibiotic effect. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43(Suppl. B):43–49. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.suppl_2.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cremieux A-C, Saleh-Mghir A, Vallois J-M, Maziere B, Muffat-Joly M, Devine C, Bouvet A, Pocidalo J-J, Carbon C. Efficacy of temafloxacin in experimental Streptococcus adjacens endocarditis and autoradiographic diffusion pattern of [14C]temafloxacin in cardiac vegetations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2216–2221. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debbia E, Schito G C, Nicoletti G, Speciale A. In vitro activity of pefloxacin against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria in comparison with other antibiotics. Chemioterapia. 1987;4:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Entenza J M, Blatter M, Glauser M P, Moreillon P. Parenteral sparfloxacin compared with ceftriaxone in treatment of experimental endocarditis due to penicillin-susceptible and -resistant streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2683–2688. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.12.2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Entenza J M, Vouillamoz J, Glauser M P, Moreillon P. Efficacy of trovafloxacin in treatment of experimental staphylococcal or streptococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:77–84. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fung-Tomc J C, Gradelski E, Huczko E, Dougherty T J, Kessler R E, Bonner D P. Differences in the resistant variants of Enterobacter cloacae selected by extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1289–1293. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoellman D B, Lin G, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Anti-pneumococcal activity of gatifloxacin compared with other quinolone and non-quinolone agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:645–649. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson C C. In vitro testing: correlations of bacterial susceptibility, body fluid levels, and effectiveness of antibacterial therapy. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 4th ed. The Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 813–834. Co, Baltimore, Md. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewin C S. Antibacterial activity of a 1,8-naphthyridine quinolone, PD 131628. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:353–357. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewin C S, Morrissey I, Smith J T. The fluoroquinolones exert a reduced rate of kill against Enterococcus faecalis. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1991;43:492–494. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb03520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrissey I. Bactericidal activity of trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:1061–1066. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrissey I. Bactericidal index: a new way to assess quinolone bactericidal activity in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:713–717. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. NCCLS document no. M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents. NCCLS document no. M26-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schick D G, Canawati H N, Montgomerie J Z. In vitro activity of the combination of trovafloxacin and other antibiotics against enterococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]