SUMMARY

Social interaction deficits seen in psychiatric disorders emerge in early-life and are most closely linked to aberrant neural circuit function. Due to technical limitations, we have limited understanding of how typical versus pathological social behavior circuits develop. Using a suite of invasive procedures in awake, behaving infant rats, including optogenetics, microdialysis, and microinfusions, we dissected the circuits controlling the gradual increase in social behavior deficits following two complementary procedures—naturalistic harsh maternal care and repeated shock alone or with an anesthetized mother. Whether the mother was the source of the adversity (naturalistic Scarcity-Adversity) or merely present during the adversity (repeated shock with mom), both conditions elevated basolateral amygdala (BLA) dopamine, which was necessary and sufficient in initiating social behavior pathology. This did not occur when pups experienced adversity alone. These data highlight the unique impact of social adversity as causal in producing mesolimbic dopamine circuit dysfunction and aberrant social behavior.

In brief

Social interaction deficits seen in psychiatric disorders emerge in early life and are most closely linked to neural circuit dysfunction. Due to technical limitations, we have limited understanding of how social behavior circuits develop. These data highlight social adversity and elevated dopamine in amygdala as causal in producing aberrant social behavior.

INTRODUCTION

Disrupted social behavior is a core symptom of many psychiatric and developmental disorders, including autism, anxiety, and depression (Miller, 2007, Kennedy and Adolphs, 2012, Crawley, 2004, Patel et al., 2019). The ontogeny of these disorders is poorly understood, but clinical research has identified early adversity as a significant risk factor in the scaffolding of lifelong social deficits (Teicher et al., 2002, Teicher et al., 2003, Malter Cohen et al., 2013, Gee et al., 2013, Hanson et al., 2015, Tottenham, 2012, Raineki et al., 2012, Raineki et al., 2015). More recent evidence suggests that adversity within the social context of the attachment figure renders the infant uniquely vulnerable (Raineki et al., 2019). Using invasive circuit dissection techniques previously impossible in pups, here we ask how the maternal signal becomes compromised during repeated social adversity and highlight the role of the amygdala-mesolimbic dopamine system’s unique functioning within a social context.

Focusing on infancy rather than later-life outcome, we used a combination of naturalistic and deconstructed adversity procedures with the caregiver to identify causal mechanisms and the developmental roots of later-life pathology. Together with adapting optical circuit dissection techniques for very young pups, this approach permitted us to demonstrate a specific ventral tegmental area (VTA)-BLA circuit targeted by early social adversity and controlling social behavior with the attachment figure and peers. Our results are seen within the context of a broader literature that has identified the amygdala and mesolimbic dopamine signaling as critical targets of adversity and later-life intervention in human and animal models (Roelofs et al., 2009, Atzil et al., 2017, Huang et al., 2016).

The amygdala plays an important role in adult social behavior (Raineki et al., 2012, Brothers et al., 1990, Rasia-Filho et al., 2000, Amaral, 2002). Although the human amygdala appears functional in fear as early as 6–9 months of age (Graham et al., 2016, Jessen and Grossmann, 2014), its role in infant social behavior is less well understood. There is evidence that the infant and adult amygdala function differently in social behavior. For example, bilateral amygdala lesions impair social behavior in the non-human primate adult, but not the infant (Bachevalier et al., 2001, Goursaud and Bachevalier, 2007, Raper et al., 2014). Recent work in infant rodents suggests that amygdala engagement is atypical in infant social behavior and that its premature engagement, potentiated by previous adversity, serves as a brake on social approach toward the caregiver (Raineki et al., 2019). This developmental specificity in amygdala function is in line with the unique ecological niche of the infant, promoting an early social behavior bias toward approaching the mother under threat and safety (Coss and Penkunas, 2016, Shultz et al., 2018, Moriceau and Sullivan, 2006, Fox et al., 2005).

Social decision-making involves evaluation of social stimuli as safe or threatening, a process known to involve dopaminergic innervation of the BLA (Zweifel et al., 2011, Rosenkranz and Grace, 2002). This BLA dopamine is primarily from the VTA, which is known to innervate the BLA in early infancy (Brummelte and Teuchert-Noodt, 2006, Niederkofler et al., 2015, Barr et al., 2009). Dopamine disinhibits BLA principal neurons to promote synaptic plasticity (Chu et al., 2012), and BLA dopamine-1 (D1) receptor overexpression impairs threat/safety evaluation (Ng et al., 2018). In addition to threat and reward, the VTA has been implicated in multiple aspects of social behavior, and VTA dopamine release bidirectionally controls social approach behavior in adult rodents (Gunaydin et al., 2014, Garrido Zinn et al., 2016, Rodriguiz et al., 2004). Although the neural circuitry supporting social behavior is complex, we focus on the VTA-BLA interface, which we recently identified as a site of integration of the effects of development, adversity, and social context (Opendak et al., 2019).

Clinical research has shown that early trauma associated with the caregiver is linked with unique detrimental outcomes, with rodent data suggesting that the social context of adversity alters trauma processing (Opendak et al., 2019, Opendak et al., 2020, Bryant, 2016, Halevi et al., 2016). The dopamine system conveys this social context, as maternal inputs robustly modulate brain-wide dopamine during typical development (Andersen et al., 1992, Kehoe et al., 1998, Tamborski et al., 1990, Barr et al., 2009). Here, our goal was to delineate the effects of social trauma versus non-social trauma on infant brain circuits carrying social value and controlling the development of social behavior. To accomplish this, we compared two different adversity paradigms: naturalistic adversity rearing with harsh maternal care versus a deconstructed adversity paradigm, isolating the social context. We found that repeated social adversity, rather than adversity experienced alone, resulted in gradually degraded caregiver regulation of the infant and persistently elevated BLA dopamine; this increase was causal in initiation and expression of social behavior pathology, as demonstrated by optogenetic and pharmacological dopamine control in the very young infant. Taken together, these data highlight mesolimbic dopamine circuit organization and function as a potential therapeutic target in understanding behavioral deficits associated with psychiatric disorders.

RESULTS

Experiment 1

Early adversity perturbs infant social behavior through heightened amygdala engagement

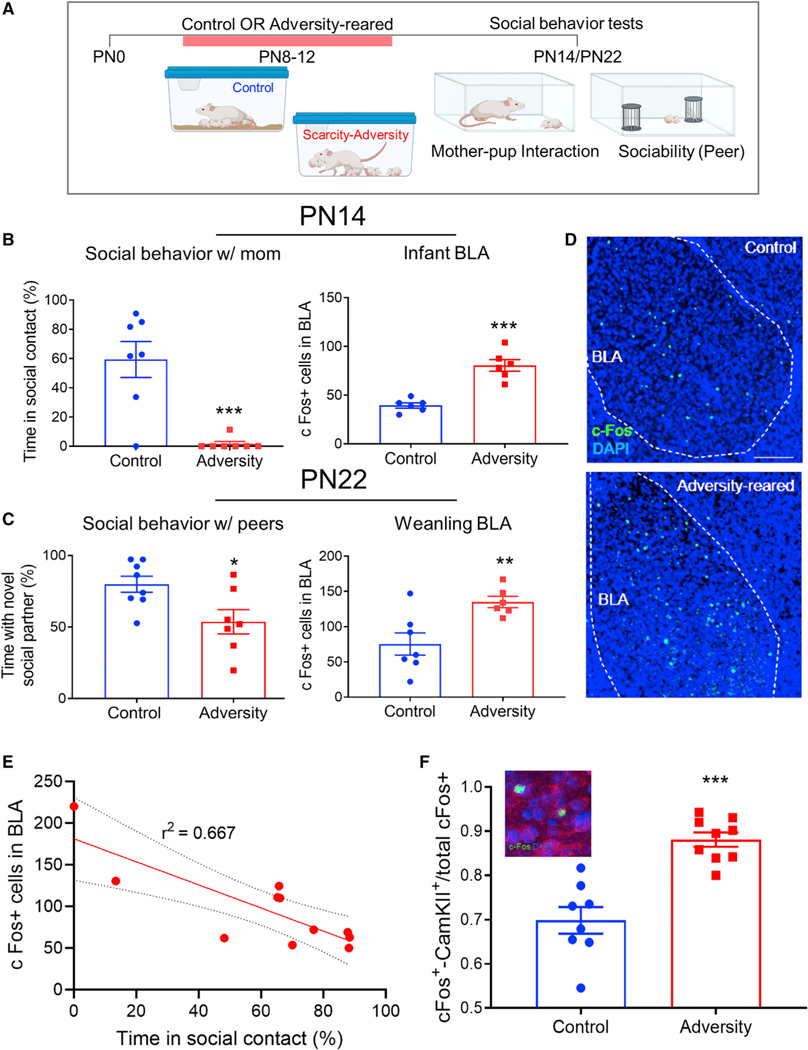

Research in children shows robust social behavior deficits as an early indicator of psychopathology, particularly with antecedents in trauma. These social behavior deficits are associated with unique patterns of amygdala activation (Tottenham et al., 2011, Skuse et al., 2003). To model adversity-rearing in rodents, we used the Scarcity-Adversity procedure in which the dam is provided with limited bedding resources from pup ages PN8–12; this causes the dam to handle pups roughly but pups gain weight normally (see Table S1). This age range is a sensitive window for scaffolding lasting socio-affective behaviors in the rodent (Opendak et al., 2020, Raineki et al., 2010). On PN13–14, we assessed social behavior in infants interacting with the mother outside the nest and observed decreased time spent nursing in Scarcity-Adversity-reared (“Adversity” in Figure) compared to control-reared pups (Figure 1B, t(12) = 4.658, p < 0.001) and increased BLA c-Fos expression of Scarcity-Adversity-reared (t(10) = 2.656, p < 0.001). The BLA c-Fos counts and perturbed social behavior shown in Figures 1A–1D provide internal replication of our previous work (Raineki et al., 2019, Rincón-Cortés and Sullivan, 2016). Adversity-reared weanling rats also showed decreased social approach toward a novel peer (t(13) = 2.624, p = 0.021) and increased BLA c-Fos expression compared to control-reared rats (Figures 1C and 1D), (t(11) = 3.243, p = 0.008). As shown in Figure 1E, we observed a significant negative correlation between Fos expression and social approach behavior in adversity-reared pups (Pearson r2 = 0.666, p = 0.002). The majority of Fos+ cells were CamKII+ principal neurons (Figure 1F; one sample t test comparison to 50%: Control: t(7) = 6.583, p = 0.0003; Adversity: t(8) = 23.6, p < 0.0001); this proportion increased in adversity-reared pups (t(15) = 5.521, p < 0.0001).

Figure 1. Early adversity is associated with atypical social behavior with mother and peers and heightened amygdala activity.

(A) Experimental timeline involving a period from pup PN8–12 in which the mother is provided either typical or limited bedding (Scarcity-Adversity-rearing), causing her to roughly handle pups while pups gain weight normally (see Table S1).

(B) In PN13 pups, adversity-rearing is associated with decreased time spent nursing in the testing apparatus and increased c-Fos in the BLA after testing.

(C) These patterns persist through weaning age during a test of social approach toward a novel peer.

(D) Representative c-Fos staining in BLA; scale bar: 50 mm.

(E) Correlation between social behavior and Fos counts in BLA generated from a separate cohort.

(F) Proportion of c-Fos labeled cells that are double-labeled with CamKII; representative photo shown in inset. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

See also Table S1

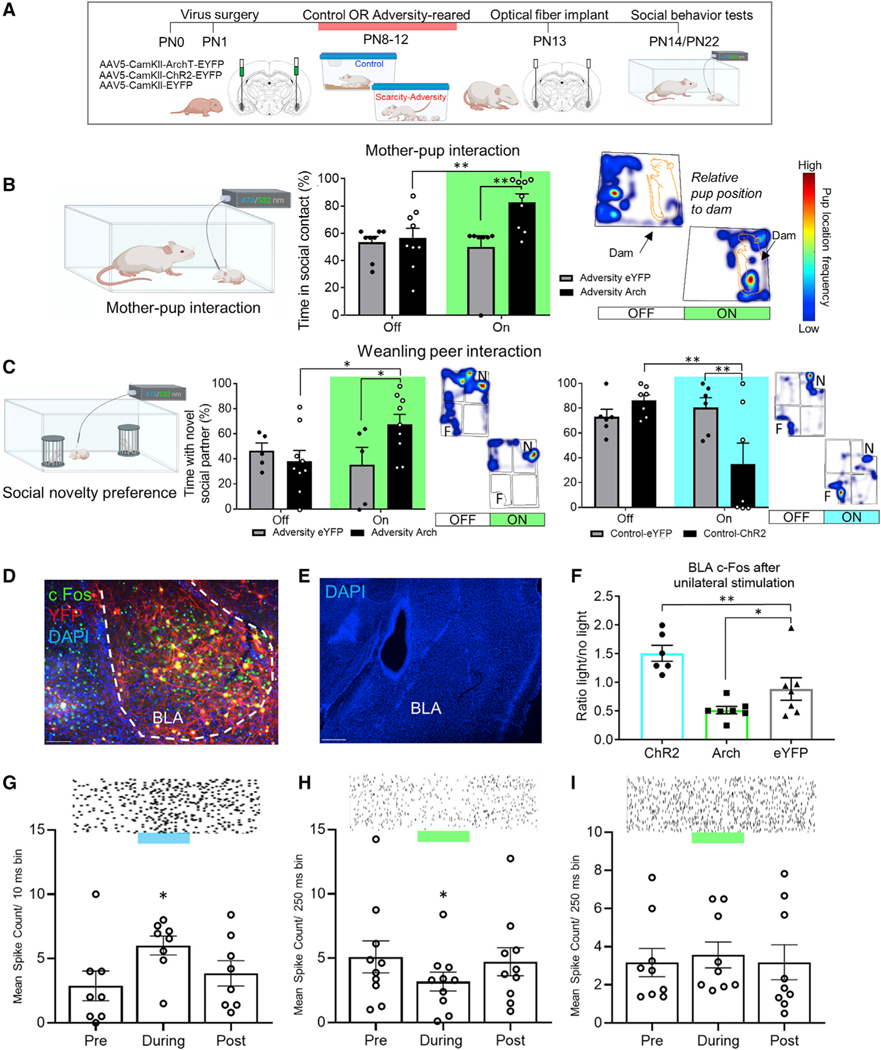

We have recently demonstrated a causal role for BLA engagement in social perturbation whereby muscimol infusion into this region rescued typical-approach behavior following early caregiving adversity (Raineki et al., 2019). Together with the Figure 1 results showing adversity-related BLA hyperactivity in the context of social deficits, these data suggest that BLA engagement is low in controls relative to adversity-reared pups and its engagement perturbs social approach. To test this in a more temporally confined and cell-specific manner, we adapted optogenetics for the very young pup (Figure 2A). Pups were transduced with AAV5-CAMKII-ArchT-EYFP or AAV5-CAMKII-EYFP into the BLA at PN1. As a tool to naturalistically modulate amygdala activation, pups were reared in control or Scarcity-Adversity conditions from PN8–12. Following optical fiber implant into the BLA at PN13 and recovery, pups were tested with a dam at PN14–15 with alternating bouts of 532 nm light on or off (see detailed Optogenetics Methods). Consistent with previous research, adversity-rearing was associated with decreased social approach toward the mother. However, inhibition of the BLA with 532 nm light increased social approach toward the mother in adversity-reared pups (Figure 2B). We observed a significant interaction between virus (AAV5-CamKII-ArchT-eYFP versus AAV5-CamKII-eYFP) and light on/off (F(1,29) = 5.218, p = 0.03). We also observed a main effect of virus (F(1,29) = 7.51, p = 0.021; no main effect of light F(1,29) = 3.013, p = 0.093). Post hoc comparisons showed that ArchT-transduced pups spent more time in contact with the mother when the 532-nm light was on (t(29) = 2.985, p = 0.006). This was not observed in control-reared pups (Figure S1A; light on versus off: t(17) = 0.244, p = 0.81).

Figure 2. Amygdala engagement controls social approach in young pups (A) Experimental timeline.

(B) At PN14, amygdala inhibition rescued social approach toward the dam in adversity-reared pups (time spent near mom/total length of light-on bout; heatmap shows highest frequency of pup location in red). With the light off, pups stays with the mother but shows an atypical behavior (i.e., stays behind the mother or farther from the mother), whereas when the light is on, pup location reverts to the typical phenotype (i.e., at mother’s ventrum).

(C) BLA stimulation decreases percent time spent near the novel peer (“N,” versus familiar, “F”) in control-reared pups, while increasing time spent with the novel peer in adversity-reared pups.

(D and E) Example of histological verification of optical fiber track, virus spread, location, and c-Fos labeling; scale bars, 50 μm, 200 μm.

(F) c-Fos expression confirmed light-controlled neural activation in the BLA.

(G–I) Mean spike count per time bin for ChR2, ArchT and eYFP transduced units, with example raster plots.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figure S1

In older pups, our lab and others have previously observed that early adversity perturbs social behavior with peers. In a test of social novelty preference (Figure 2C), adversity-reared pups spent less time with a novel peer than with a littermate, compared to controls (t(9) = 3.061, p = 0.014). Engagement of the BLA also controlled this behavior: suppressing BLA neurons with the 532 nm light increased time spent with the novel peer (significant interaction between virus and light, F(1,24) = 0.047; p = 0.047; no main effects of virus, F(1,24) = 1.521, or light F(1,24) = 0.878). Post hoc comparison showed that ArchT-transduced pups spent more time near the novel peer when the light was on (t(24) = 2.537, p = 0.018). The light did not affect time with the novel peer in eYFP-transduced pups (t(24) = 0.723, p = 0.477). Finally, suppressing BLA neurons of control-reared pups with the 532 nm light had no effect on approach behavior toward peers (Figure S1B; light on versus off: t(34) = 1.456, p = 0.155).

Conversely, enhanced amygdala activation was associated with decreased time spent with the novel peer in control-reared pups. Following infusion of AAV5-CAMKII-ChR2-eYFP or AAV5-CAMKII-eYFP and optical fiber implantation into the BLA at PN1, we observed a significant interaction between virus and a 473-nm light on/off (F(1,22) = 7.794, p = 0.011) and a main effect of light (F(1,22) = 4.355, p = 0.049; ; no main effect of virus, F(1,22) = 2.373, p = 0.138). Post hoc comparison showed that ChR2-transduced pups spent less time near the novel peer when the light was on (t(22) = 3.591, p = 0.002). The light did not affect time with the novel peer in eYFP-transduced pups (t(22) = 0.48, p = 0.636). During the period of habituation to the testing apparatus, light presentation was not associated with any changes in time spent near the empty novel peer chamber (see Figure S1C).

To validate optical control of amygdala neurons after 2–3 weeks of infection, we assessed c-Fos expression following light presentation. As shown in Figure 2F, stimulation with the 473-nm light enhanced c-Fos expression (ratios of c-Fos in hemisphere with fiber plugged in versus hemisphere with no fiber). We observed less c-Fos expression in ArchT-transduced pups when the 532 nm light was used, whereas control pups transduced with AAV5-eYFP showed no effect of light on c-Fos (one way ANOVA across virus type, F(2,17) = 11.54, p = 0.001). Comparisons of c-Fos density values with light on versus off are included in Figure S1D: two-way ANOVA shows a significant interaction between light on/off and opsin (F(2,35) = 3.42, p = 0.044; no main effect of virus, F(2,35) = 0.522, p = 0.598, or light on/off, F(1,35) = 0.14, p = 0.711). Post hoc comparisons show an increase in c-Fos expression when the light is on for ChR2-transduced cells (p = 0.044), whereas light on for Arch-transduced cells was associated with decreased c-Fos expression (p = 0.034); we observed no effect of light on c-Fos expression in eYFP-transduced cells (p = 0.398).

A second validation of the efficacy of our optical control procedures utilized an in vivo analysis of optical manipulation of sensory-evoked responses in the BLA of pups that were transduced with virus or eYFP control. A custom optrode was lowered into the BLA of urethane-anesthetized pups, and laser stimulation was presented and signals recorded (ArchT-transduced: 2 s of 532-nm light with 200-ms ramp down presented every 10 s; ChR2-transduced: 10-ms flashes at 473 nm, every 10 s; see Methods). As shown in Figure 2G, ChR2-transduced pups demonstrated a light-evoked increase in unit responses (repeated-measures one-way ANOVA across time, F(2,10) = 5.462, p = 0.032). ArchT-transduced pups demonstrated a light-evoked suppression of unit responses (Figure 2H; F(2,14) = 9.74, p = 0.004). As a recent report showed that sustained activation of archaerhodopsin in presynaptic terminals can eventually induce vesicular release and rebound bursting immediately after termination of the light (Mahn et al., 2016), rebound effects were minimized through the use of a 200-ms ramp down (responses to square wave stimulation are shown in Figure S1F). We did not observe an effect of light on unit responses in eYFP-transduced controls (Figure 2I; F(2,14) = 1.046, p = 0.373).

Experiment 2

Failure of maternal neurobehavioral regulation (social buffering) in adversity-reared pups

Elevated amygdala activation during social testing suggests that adversity perturbs processing of socially relevant cues, which has been shown to undergo experience-dependent plasticity in pups (Perry et al., 2016). To test this hypothesis, we developed a procedure to pinpoint changes in pup social processing of the caregiver. Following control or Scarcity-Adversity-rearing, we assessed pup neurobehavioral responses to a mild tail shock when exposed alone or in the presence of the mother. This capitalized on the typical ability of the caregiver’s presence to decrease the infant’s neurobehavioral response to threat across species from rodents to humans, a process which can be compromised in infants with low-quality care (Hostinar et al., 2014).

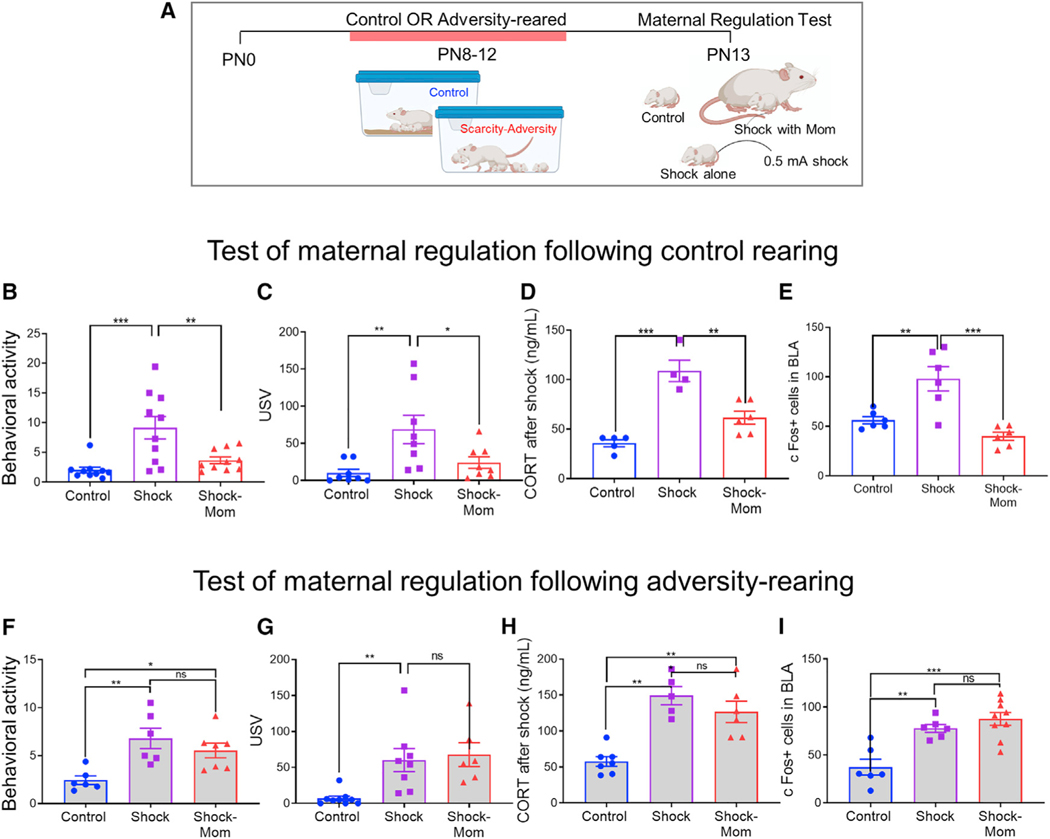

In this procedure, pups were control or Scarcity-Adversity-reared from PN8–12 and on PN13, removed from the nest and either placed alone in a beaker or in a chamber with an anesthetized mother for 45 min. Pups then received 0.5-mA shocks either alone or in the presence of the mother every 5 min (9 shocks total) while a third group placed alone in a beaker received no shocks (Figure 3A). As shown in Figures 3B–3D, shock experienced alone increased control pups’ neurobehavioral responses to the shock, including physical activity and ultrasonic vocalizations, while the presence of the mother blocked these responses to unshocked levels (activity: F(2,45) = 15.71, p < 0.001; USV: F(2,21) = 6.318, p = 0.007). Similarly, pup plasma corticosterone levels were elevated in response to shock, but only if pups were alone (F(2,12) = 24.41, p < 0.001). Post hoc tests show that the presence of the mother during shock brings all measures to control levels (Activity: control versus shock [t(45) = 5.433, p < 0.001], control versus shock with mom [t(45) = 1.523, p = 0.135], shock versus shock with mom: [t(45) = 3.909, p < 0.001]; USV: control versus shock [t(21) = 3.404, p = 0.003], control versus shock with mom [t(21) = 0.8146, p = 0.424], shock versus shock with mom: [t(21) = 2.598, p = 0.017]; CORT: control versus shock [t(12) = 6.939, p < 0.001], control versus shock with mom [t(12) = 2.708, p = 0.057], shock versus shock with mom: [t(12) = 4.671, p = 0.002]). The mother’s presence during acute shock exposure buffered the amygdala response, as measured by BLA c-Fos expression (Figure 3E; F(2,21) = 8.68, p = 0.002).

Figure 3. Effects of early caregiving on maternal regulation of infant neurobehavioral response to brief threat.

(A) Experimental paradigm.

(B–I) Measure of pup physical activity, ultrasonic vocalizations, plasma CORT, and amygdala c-Fos in response to shock alone or with the mom on control- and adversity-reared pups.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In adversity-reared pups, this effect of maternal presence was not observed (Figures 3F–3I). Regardless of maternal presence, shock increased pup activity ([F(2,16) = 7.356, p = 0.05], control versus shock [t(16) = 3.758, p = 0.002], control versus shock-mom [t(16) = 2.782, p = 0.013], shock versus shock-mom [t(16) = 1.18, p = 0.28]). This was also observed with pup USV, which increased to a similar extent whether pups were shocked alone or with the mother present ([F(2,20) = 7.555, p = 0.004], control versus shock [t(20) = 3.2, p = 0.005], control versus shock with mom [t(20) = 3.377, p = 0.003], shock versus shock-mom [t(20) = 0.426, p = 0.682]). Maternal presence similarly failed to buffer pup plasma corticosterone increases associated with shock ([F(2,15) = 18.04, p < 0.001], control versus shock [t(15) = 5.588, p < 0.001], control versus shock with mom [t(15) = 4.432, p < 0.001], shock versus shock-mom [t(15) = 1.133, p = 0.203]). Finally, the mother failed to buffer BLA c-Fos activation in response to shock ([F(2,18) = 14.75, p < 0.001], control versus shock [t(18) = 3.89, p = 0.001], control versus shock with mom [t(18) = 5.302, p < 0.001], shock versus shock-mom [t(18) = 1.041, p = 0.312]).

Experiment 3

Assessing infant social circuit dynamics within a controlled laboratory paradigm

Thus far, we have used the naturalistic model of Scarcity-Adversity to show that the antecedents of altered social behavior may be perturbed amygdala processing of social cues. This appears to be a two-step process, in which failed infant regulation by an adversity-rearing mother is followed by lasting amygdala hyper-activity and social deficits. However, several questions remain following this ethological assessment. First, what are the specific features of adversity that produce altered social processing and social behavior? Second, what are the circuit mechanisms for these effects?

To address these questions, we sought to identify the role of social context during adversity in perturbing circuit dynamics. Although the Scarcity-Adversity paradigm provides a naturalistic model with high translational validity (Perry et al., 2016), this procedure is complex and prevents assessment of specific features of experience that influence the developing brain. It was there-fore necessary to pare down the adversity procedure in such a fashion that ongoing effects could be assessed while recapitulating the phenotype of the more naturalistic paradigm. We therefore adapted the shock-with-mom procedure described above (Experiment 2) to track the ongoing effects of repeated adversity with the mother, hereafter called “Deconstructed Adversity.” Here, control-reared pups were removed from the nest and received mild tail shocks every 5 min for 90 min (18 shocks total) daily from PN8–12. This either occurred in the presence of an anesthetized dam (Shock w/ Mom) or alone (Shock), with a third group receiving no shocks (Control).

As shown in Figure 4, this procedure produces similar long-term outcomes as the Scarcity-Adversity procedure, while permitting us to assess with greater precision the progression of responses to the trauma. Importantly, this procedure also permits us to distinguish between the effects of adversity alone and adversity experienced within a social context. In addition, the repeated shock-mom procedure permits invasive mechanistic approaches described below (e.g., microinfusions) that would be difficult or near-impossible within the Scarcity-Adversity procedure.

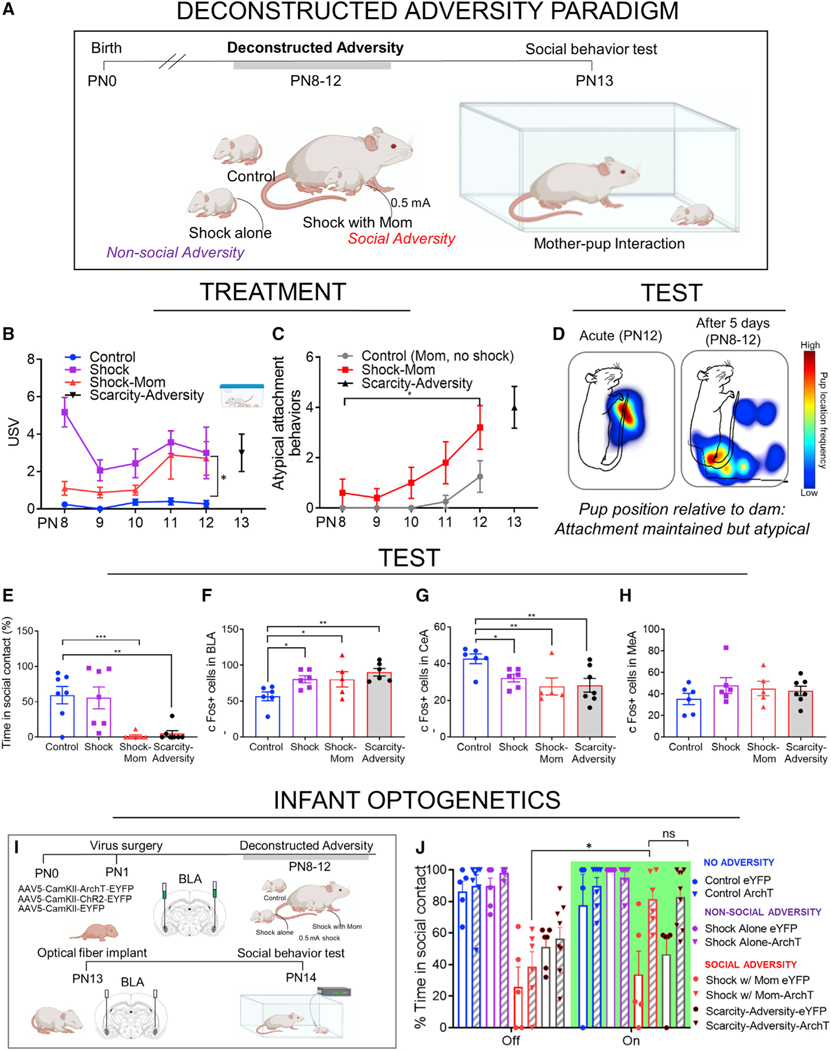

Figure 4. Gradual degraded salience of maternal cue and impaired social behavior across 5-day procedure.

(A) Experimental timeline with gray bar indicating PN8–12 procedure. To facilitate visual comparison across different adversity paradigms, a Scarcity-Adversity icon is included in B, although this group is included in all graphs.

(B) Gradual increase in USV over 5 days of procedure.

(C) Gradual increase in atypical attachment behaviors toward the mother across 5-day procedure, compared to pups placed with the mom and receiving no shocks.

(D) Heatmap showing pup position relative to dam after 1 day of shock on PN12 versus 5 days (8–12), with highest frequency of pup location in red. On one day of shock with mom, pups show typical behavior (stay at ventrum), whereas after 5 days, pup location is atypical.

(E) Five days of repeated exposure with the mom is associated with decreased approach toward the dam in nipple-attachment test.

(F–H) Markers of amygdala activity are no longer buffered by mom after 5 days of repeated adversity with the mother.

(I) Timeline of optogenetic manipulation with deconstructed adversity procedure.

(J) At PN14, amygdala inhibition rescued social approach toward the dam in social adversity-reared pups (repeated shock with mom [red] and Scarcity-Adversity [black with red outline]).

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figures S2 and S3

During treatment, pups repeatedly shocked in mother’s presence show gradual loss of social buffering to shock, as well as increased atypical attachment behaviors

Across the 5-day procedure, we assessed pup behavioral responses to the dam and shock within the testing chamber. We observed a gradual decrement in the ability of the mother’s presence to buffer pup neurobehavioral responses to the shock. In USVs, we observed a main effect of condition (F(2,63) = 30.34, p < 0.001) and a main effect of day (F(4,63) = 2.734), with no significant interaction (F(8,63) = 2.007, p = 0.059). On the first day of the procedure, shock-mom pups emitted fewer USVs than pups shocked alone (t(63) = 6.636, p = 0.001). By Day 5 of the procedure, USVs with the mother were no different from USVs by pups shocked alone (p > 0.99). Day 5 USVs in shock-mom pups were not significantly different from USVs emitted by adversity-reared pups (t(9) = 0.219, p = 0.832) (Figure 4B).

Whereas pups removed from the nest typically approach the dam and nurse, atypical behaviors such as sleeping behind the mother’s back or failing to approach the dam were also assessed. A repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated a main effect of condition (Figure 4C, control versus shock-mom; [F(1,10) = 13.94, p = 0.004]) and a main effect of procedure day [F(4,40) = 6.043]; no significant interaction [F(4,40) = 1.762, p > 0.05]). By day 5 of the procedure, atypical social behavior toward the mother was significantly increased compared with day 1 (t(40) = 4.165, p = 0.002) in the shock-mom pups, and by Day 3 (PN10), atypical responses to the mother were significantly increased compared with controls (t(50) = 2.963, p = 0.005). Atypical behaviors by day 5 were not distinct from atypical behaviors in Scarcity-Adversity-reared pups tested at PN13 (t(9) = 0.662, p = 0.524).

Repeated social adversity impacts neurobehavioral measures during social testing

In order to assess the cumulative effects of the 5-day shock-mom procedure, pups were assessed in a social behavior test with the dam on PN13 (no shocks received) and then brains removed for neural assessment. It is important to note that the testing procedures (even without shock) are slightly stressful and therefore may uncover pup neurobehavioral deficits other-wise undetectable in the nest environment (see Figure S2). Following the gradual increase in atypical attachment behavior observed over the course of the shock-with-mom procedure (Figures 4B–4D), pups tested on PN13 showed a dramatic decrease in social approach behavior toward the mother (Figure 4E, [F(3,24) = 9.635, p = 0.002]). Post hoc tests showed that approach was decreased compared to controls and shock-alone pups (control versus shock [t(18) = 0.239, p = 0.814]; control versus shock-mom [t(18) = 3.582, p = 0.002], shock versus shock-mom [t(18) = 3.343, p = 0.004]). Pups exposed to repeated shock with mom showed similar levels of atypical behavior to adversity-reared pups in this procedure (t(24) = 0.233, p = 0.818). As illustrated in Figure S3, while pups at this age can learn an aversion to an odor, this does not occur with maternal odor.

Similarly, 5 days of repeated shock-mom exposure prevent the mother from buffering the effect of shock on amygdala activity (Figures 4F–4H). We assessed c-Fos expression after the PN13 social behavior test. In the BLA, we observed group effects (F(3,19) = 4.622, p < 0.001) across treatment conditions. Post hoc tests showed that both shock treatments increased c-Fos expression in the BLA, to a similar degree as naturalistic Scar-city-Adversity (control versus shock [t(19) = 2.536, p = 0.02]; control versus shock-mom [t(19) = 2.408, p = 0.026], shock versus shock-mom [t(19) = 0.007, p = 0.99], shock-mom versus Scarcity-Adversity [t(19) = 1.005, p = 0.328]). Similar patterns were observed in the central amygdala ([F(3,20) = 4.232, p = 0.018]; post hoc: control versus shock [t(20) = 2.2, p = 0.04]; control versus shock-mom [t(20) = 3.01, p = 0.007], shock versus shock-mom [t(20) = 0.91, p = 0.327], shock-mom versus Scarcity-Adversity [t(20) = 0.129, p = 0.898]). These effects were not observed in the medial amygdala (F(3,20) = 0.827, p = 0.4943, all comparisons p > 0.05). Overall, these effects were in strong contrast to the mother’s blockade in the acute shock procedure for control-reared pups (Experiment 2).

Together, these data suggest that—similar to the Scarcity-Adversity rearing—the deconstructed social adversity of repeated shock with the mother results in a decreased ability of the mother to regulate the neurobehavioral response to threat. This is evident in amygdala activity, which is associated with a gradual but dramatic decrease in pup social approach toward the mother. Importantly, repeated shock experienced alone did not produce these outcomes.

Social adversity perturbs social approach through BLA engagement

To verify that the deconstructed social adversity procedure engaged a similar circuit as the naturalistic Scarcity-Adversity procedure, we performed optogenetic manipulations on pups performing social behavior tasks following this early paradigm. Pups were transduced with AAV5-CamKII-ArchT-EYFP or AAV5-CamKII-EYFP into the BLA at PN1, followed by deconstructed adversity (repeated shock with mom, “Social-Adversity,” shock alone, “Non-social Adversity,” or control “No Adversity”) from PN8–12. Following optical fiber implant into the BLA at PN13 and recovery, pups were tested with a dam at PN14–15 with alternating bouts of a 532-nm light on or off (Figure 4I). Pups that had previously undergone the social adversity procedure showed decreased approach toward the mother, which could be rescued by inhibition of the BLA with 532 nm light (Figure 4J). Two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant interaction between group and light (F(7,80) = 2.356, p = 0.031). Post hoc comparisons showed that ArchT-transduced pups that experienced deconstructed social adversity (shock with mom) spent more time in contact with the mother when the 532-nm light was on (t(80) = 3.716, p < 0.001). Importantly, the response to light in ArchT-transduced pups was similar regardless of the type of social adversity (two-way ANOVA deconstructed versus Scarcity-Adversity, F(1,26) = 1.151, p = 0.293). There was no observed impact of light in pups that were in the non-adversity control group or pups that experienced non-social adversity (all comparisons p > 0.05).

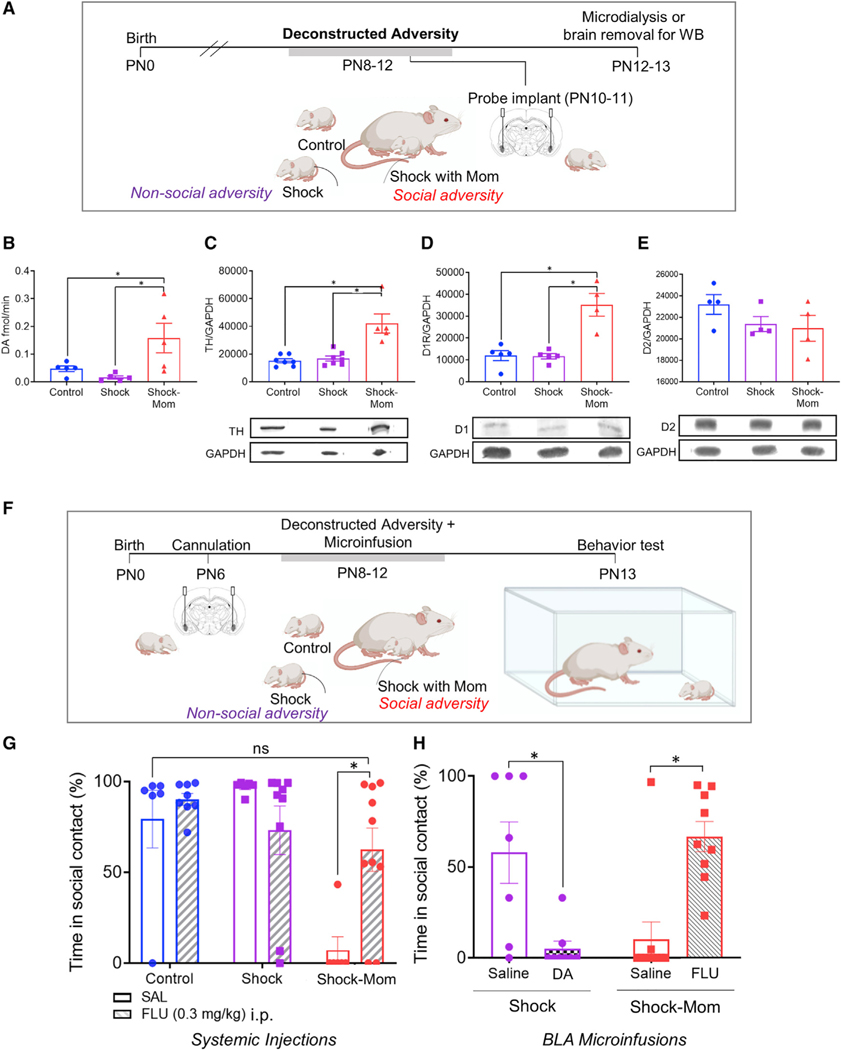

Social adversity elevates dopamine markers in the BLA

To assess changes in circuit-level processing of the maternal cue following repeated adversity with the mother, we performed microdialysis in the BLA of pups that underwent the Deconstructed Adversity procedure (Figure 5A). Following probe implantation in the BLA at PN10–11, microdialysate was collected at PN13. HPLC showed that shock with the mother was associated with a specific increase in dopamine efflux (Figure 5B) (F(2,12) = 5.666, p = 0.019), shock-mom versus control (t(12) = 2.492, p = 0.028), shock-mom versus shock (t(12) = 3.206, p = 0.008)].

Figure 5. Dopamine in the BLA is causal in perturbed social behavior with the mom.

(A) Experimental timeline including daily treatment and microdialysis.

(B) Dopamine efflux in BLA is elevated in pups repeatedly shocked with mom.

(C–E) Western blot shows that shock with mom is associated with increased TH and D1 expression in the amygdala.

(F) Timeline for pharmacology experiment, with gray bar showing PN8–12 treatment.

(G–H) Systemic and intra-BLA dopamine blockade during shock-mom prevents expression of impaired social behavior with the mom at PN13.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figure S4

A unique effect of maternal presence during adversity on dopamine markers was also shown using western blot in amygdalae of pups repeatedly exposed to the shock-with-mom procedure (Figures 5C–5E). We observed group differences in cytosolic TH expression and synaptic D1 receptor expression (TH [F(2,8) = 6.09, p = 0.024]; D1 [F(2,8) = 12.82, p = 0.032]). Post hoc tests showed that for both TH and D1, expression in repeated shock-mom groups was higher than both repeated shock alone and control (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). In contrast, there were no differences in synaptic D2 expression (p > 0.05, see Figure S4A for gels). We found no group differences in optical density of TH expression in the VTA and BLA (Figure S4B, BLA, t(6) = 0.694, p = 0.514; VTA, t(5) = 0.196, p = 0.853), suggesting the western blot results reflect alternative sources of plasticity.

Amygdala dopamine elevation during social adversity is causal in perturbed social behavior

Given these data highlighting the mesolimbic dopamine interaction with the BLA perturbing social processing of the mother, we next assessed causation using complementary pharmacological approaches over the course of the repeated shock-mom treatment. The goal of these studies was to test whether maternal presence during shock perturbed pup orienting toward the maternal odor through elevated dopamine in the BLA. Administering the dopamine receptor antagonist cis-z-flupenthixol (FLU; i.p., 0.3 mg/kg, Sigma) before each treatment from PN8–12 rescued typical social behavior in shock-mom pups at PN13 (Figure 5G). We observed an interaction between drug and condition (F(2,36) = 3.935, p = 0.029). We also observed main effects of condition (F(2,36) = 5.921, p = 0.006) and drug (F(1,36) = 9.645, p = 0.004). Post hoc comparisons showed a decrease in atypical attachment behavior when shock-mom pups received drug (p = 0.008) and no difference between controls receiving saline and shock-mom pups receiving systemic FLU (p = 0.993).

In order to further assess the causal role of amygdala dopamine in perturbing attachment behavior, dopamine levels were pharmacologically controlled in the BLA of pups that received shocks alone or with the mother (Figure 5F). After cannulation at PN6 and recovery in the nest, pups underwent the PN8–12 daily shock/shock-mom treatment, followed by dyadic testing at PN13. Immediately prior to each 90-min exposure, FLU, dopamine or vehicle were infused into the BLA (see Methods). We observed a significant interaction between rearing condition and drug infused (F(1,30) = 28.48, p < 0.001; no main effects of drug (F(1,30) = 0.035, p = 0.853) or condition (F(1,30) = 0.456, p = 0.504). Intra-BLA dopamine receptor blockade during the treatment resulted in a dramatic decrease in atypical attachment behavior at PN13 for shock-mom pups (t(30) = 4.16, p < 0.001). In contrast, intra-BLA dopamine infusion increased atypical attachment behavior in pups that were shocked alone (t(30) = 3.443, p = 0.001).

Experiment 4

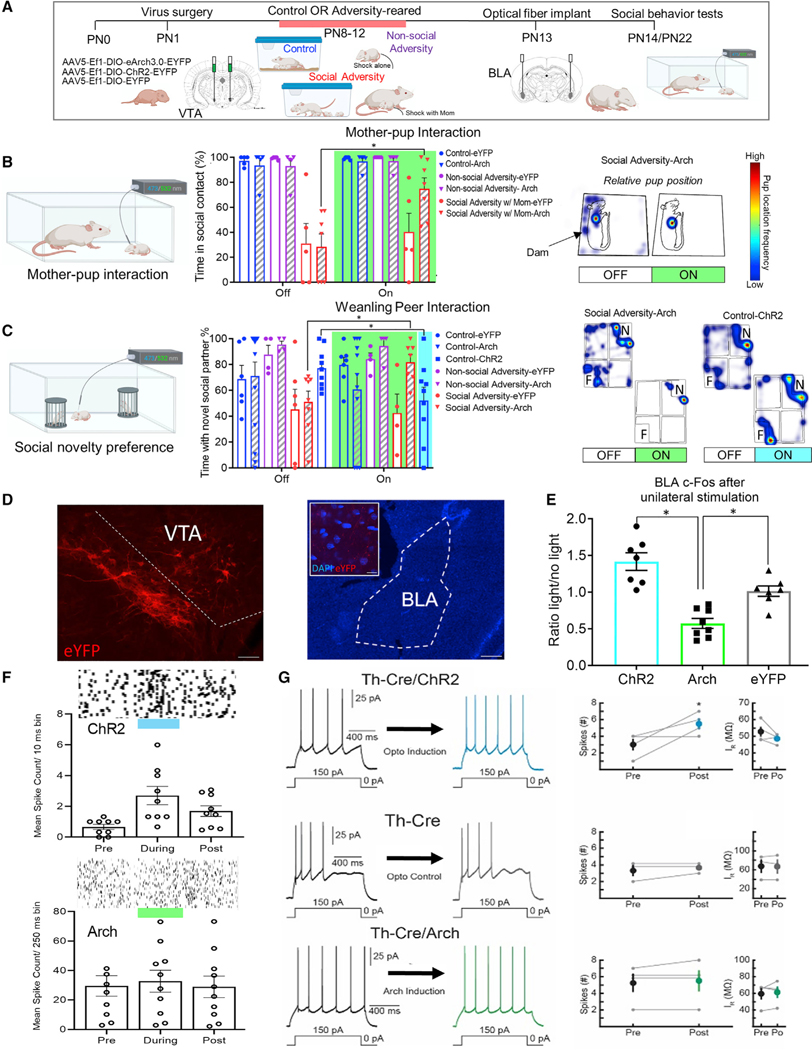

Dopaminergic innervation of pup BLA bidirectionally controls social approach behavior in young pups

The results of the Deconstructed Adversity procedure generate support for the hypothesis that the BLA-VTA interface is impacted during repeated adversity with the mother, causing perturbed social behavior. With this specific circuit identified, we used optogenetics to assess how dopaminergic innervation of the BLA controls social behavior with the mother and peers in typical and perturbed development. To specifically target dopamine neurons in the VTA, TH-Cre pup VTA neurons were transduced at PN1 with AAV5-EF1a-DIO-eArch3.0-EYFP, AAV5-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP, or AAV5-EF1a-DIO–EYFP. Pups were reared with a control, non-social adversity (repeated shock alone), and social adversity (repeated shock with the mother or Scarcity-Adversity) from PN8–12. There were no group differences between these two conditions, and therefore, they were combined for analysis (Figure S5A). Following optical fiber implant into the BLA, TH-Cre pups were tested with a dam at PN14 or in the social novelty preference test at PN22 with alternating bouts of 473/532-nm light on or off (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Dopaminergic innervation of BLA bidirectionally controls social approach behaviorin young pups.

(A) Experimental timeline.

(B) In the attachment test at PN14, suppressing dopamine release in the BLA rescued social approach toward the dam in pups reared with social adversity. Example heatmap shows pup location relative to dam. With the light off, pups stays with the mother but shows an atypical behavior (i.e., stays behind the mother or farther from the mother), whereas when the light is on, pup location reverts to the typical phenotype (i.e., at mother’s ventrum).

(C) Stimulation of VTA TH fibers in BLA decreases time spent near the novel peer in control-reared pups, while suppression of VTA TH fibers in BLA increases time spent with the novel peer in social adversity-reared pups. Example heatmap shows pup location relative to social stimuli.

(D) Example of histological verification of virus-spread, location, and optical fiber track. Scale bars, 50 μm, 200 μm. Inset shows eYFP+ fibers in BLA (scale bar, 10 μm).

(E) c-Fos expression confirmed light-controlled neural activation in the BLA (raw data shown in Figure S5C).

(F) Mean spike counts per time bin in TH-Cre pups transduced with ChR2 and Arch.

(G) Functional effect of optogenetically manipulating VTA-TH terminals in the BLA. (Top) Example of action potentials induced through current injection pre- and post-channelrhodopsin activation of VTA-TH terminals. A significant increase in the number of action potentials is measured post induction. The increase in excitability cannot be accounted for by an increase in input resistance. (Middle) Action potentials pre- and post-exposure to light in control, uninjected littermates. No change in neuronal excitability is induced purely by light exposure and no change in input resistance. (Bottom) An example of current injection-induced action potentials pre- and post-archaerhodopsin activation. Prolonged activation of archaerhodopsin did not cause an increase in neuronal excitability.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figures S5

Two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction between light and group at PN14 (Figure 6B, F(6,89) = 2.22, p = 0.048). Post hoc comparisons showed that Arch-transduced pups experiencing social adversity spent more time in contact with the mother when the 532-nm light was on (t(52) = 4.523, p < 0.001). This was not observed in Arch-transduced pups experiencing non-social adversity (t(52) = 0.33, p = 0.745) or no-adversity controls (t(52) = 0.283, p = 0.778).

Suppression of VTA fiber activity in the BLA also controlled social behavior in weanling pups, as inhibiting VTA fibers in the BLA with 532-nm light increased time spent with the novel peer in pups with social adversity (Figure 6C; significant interaction between group and light; F(6,89) = 2.22, p = 0.048). Post hoc comparison showed that Arch3.0-transduced pups that experienced social adversity spent more time near the novel peer when the light was on than off (t(89) = 2.92, p = 0.004). This was not observed for control, non-social adversity, or eYFP-transduced pups (all comparisons p > 0.05). Conversely, enhanced VTA > BLA activation was associated with decreased time spent with the novel peer in control-reared pups. When the light was on, ChR2-transduced pups spent less time near the novel peer (p = 0.045) and compared to eYFP-transduced control pups (p = 0.049). These light effects were not observed during the habituation period, when both chambers were empty (Figure S5B).

Histology confirmed virus spread and optical fiber tracks (examples shown in Figure 6D). Stimulation with a 473-nm light enhanced c-Fos expression in the BLA (Figure 6G; ratios of hemisphere with fiber plugged in versus hemisphere with no fiber). We observed less BLA c-Fos expression in Arch-transduced pups when the 532-nm light was used, with no effect of light on c-Fos in eYFP-transduced pups (F(2,19) = 23.41, p < 0.001). Comparisons of c-Fos density values are included in Figure S5C: two-way ANOVA shows significant interaction between light on/off and virus (F(2,28) = 4.396, p = 0.022; no main effect of virus (F(2,28) = 0.008, p = 0.928), or light on/off (F(1,28) = 1.46, p = 0.249). Post hoc comparisons demonstrate that light increased c-Fos expression in Chr2-transduced cells (p = 0.025), and decreased c-Fos expression in Arch-transduced cells (p = 0.013). There was no effect of light on eYFP-transduced cells (p = 0.874).

Urethane-anesthetized ChR2-transduced pups demonstrated a light-evoked increase in unit responses (Figure 6F; repeated-measures one-way ANOVA across time; F(1,9) = 17.05, p = 0.002). Responses to 532 nm light in Arch-transduced pups did not result in suppression, potentially due to low levels of spontaneous DA release in anesthetized pups. We did not observe an effect of light on unit responses in eYFP-transduced controls (Figure S5D). As with Experiment 2 above, rebound effects were minimized through the use of a 200-ms ramp down in acute optrode recordings.

We next tested whether the prolonged activation caused a significant increase in spiking activity, similar to ChR2 activation using in vitro whole-cell recording (Figure 6G). High-frequency excitation (5-ms pulse, 20Hz, 2 min) of VTA-TH projections to BLA significantly increased neuronal excitability (pre = 3 ± 0.71, post = 5.5 ± 0.65; n = 4; p = 0.04) immediately after the stimulation protocol (Figure 6G, top row). Control experiments using uninjected TH-Cre littermates showed no change (pre = 3.33 ± 0.67, post = 3.33 ± 0.33; n = 3; p = 0.21) post light stimulation (Figure 6G, middle row). Arch activation (2 min continuous) did not cause significant increase in neuronal excitability (pre = 5.25 ± 1.11, post = 5.5 ± 1.26; n = 4; p = 0.20) (Figure 6G, bottom row), indicating that our method for inhibiting VTA-TH terminals does not cause an increase in spiking in the BLA.

DISCUSSION

Although understanding social interaction deficits associated with psychiatric disorders has been challenging, neural circuit organization and function have emerged as potential therapeutic targets (Gordon, 2016, Koroshetz et al., 2018, Grossman and Dzirasa, 2019). Here, we present data supporting a specific dopaminergic-amygdala circuit involved in perturbed social cue processing and behavior in the infant rat. Using a suite of invasive procedures in awake, behaving rat pups, including optogenetics, microdialysis, and microinfusions, we charted the gradual increase in social behavior deficits associated with adversity and dissected circuits controlling this process. Using complementary approaches of ethological (naturalistic Scarcity-Adversity with a maltreating mother) and controlled (repeated shock with mother versus alone) models, we show that the social context of repeated adversity produces distinct effects from adversity experienced alone. Specifically, repeated social adversity was associated with increased dopamine release in the pup BLA. This persistently elevated dopamine was necessary and sufficient to initiate social behavior pathology, as demonstrated by disruption and replacement of dopamine during environmental perturbation and during expression of social behavior deficits with the mother and peers.

It is important to note that maternal behavior was not required for our results—the mere presence of an anesthetized mother during adversity was sufficient to mimic the complex natural nest context. Taken together, these results demonstrate a clinically relevant target for therapeutic interventions following early trauma and uncover clues about the developmental role of the amygdala in social behavior. Whether the mother was the source of the adversity (maltreating during the Scarcity-Adversity procedure) or merely present during the adversity (pups shocked with the mother), these social adversity conditions produced distinct outcomes from adversity experienced alone.

Across species, developmental research has shown correlations between adversity-rearing, amygdala dysfunction and perturbed social behavior (Tottenham, 2012, Malter Cohen et al., 2013, Gunnar et al., 2015, Callaghan et al., 2019a, Sánchez et al., 2001). Adapting optogenetics for the young awake-behaving pup, we show here that amygdala engagement was causal in decreasing social approach toward the mother and novel peers. In order to further delineate specific circuit mechanisms translating adversity-rearing to pup outcomes, we deconstructed the naturalistic adversity-rearing procedure with the goal of isolating the repeated adversity with or without the social context of the mother. This revealed that repeated shocks with the mother present phenocopied social behavior deficits and compromised processing of maternal cues following naturalistic adversity-rearing. Furthermore, social deficits required shocks paired with the mother, as pups shocked alone showed no social impairment. This is consistent with our recent data demonstrating unique effects of social context of chronic stress hormone exposure on amygdala deficits and social impairments in the pup (Raineki et al., 2019). On a broader scale, literature from across the lifespan has shown that social stimuli can engage specific neurobehavioral responses, including within the amygdala (Li et al., 2017). There is also a large literature suggesting that a social context guides the brain’s response to stress, with stress within a social context compared with a non-social context having a distinct neurobehavioral signature (Felix-Ortiz et al., 2016, Skuse et al., 2003, Modi and Sahin, 2019).

The data we have presented suggest that within the context of adversity, social approach toward the mother becomes gradually perturbed as the mother loses regulatory efficacy. This is consistent with correlational data across species demonstrating that early adversity is associated with perturbed caregiver regulation of the infant (Nachmias et al., 1996, Callaghan et al., 2019b, Pratt et al., 2019). Using a rodent model permitting assessment during adversity, we recently demonstrated that a possible mechanism for impaired regulation may be a decrease in salience of nurturing maternal inputs, such as milk and grooming. These inputs typically produce a transient but dramatic change in oscillatory power but fail to regulate infant cortical oscillations within the context of maternal rough handling of pups (Opendak et al., 2020).

The current experiments expand upon this to highlight the role of amygdala dopamine in modulating the salience of the caregiver in the infant brain. We have known for decades that maternal inputs decrease pup dopamine activity (Tamborski et al., 1990, Kehoe et al., 1998, Andersen et al., 1992, Barr et al., 2009) and that dopamine gates amygdala plasticity to promote threat learning (Rosenkranz and Grace, 2002, Barr et al., 2009). Using invasive approaches previously impossible in awake-behaving pups, the present results suggest that consistently elevated dopamine in the basolateral amygdala during adversity-rearing causes social deficits through atypical VTA-amygdala circuit engagement. In light of the known role of dopamine in assigning stimulus valence and salience (Zweifel et al., 2011, Anstrom et al., 2009), one interpretation is that this failed dopamine regulation results in persistent changes in evaluating a social stimulus. This is consistent with our data showing that adversity-rearing perturbs maternal regulation of the infant dopamine system and amygdala activation during fear/threat conditioning (Opendak et al., 2019). Importantly, our results demonstrate that the VTA-BLA circuit controls peer social behavior as well. Notably, we observed a developmental change in the expression of deficits: in younger pups, adversity-induced VTA-BLA hyper-engagement was associated with decreased approach toward the mother. In contrast, older pups showed an increase in relative preference for a familiar littermate. These developmental alterations may reflect a changing role for dopamine in social behavior as pups transition from mother-directed social behavior to a balance of avoidance and approach as they prepare for independence and navigating complex social hierarchies. These functions involve evaluating novelty, salience, reward, aversion, and learned safety signals (Berridge and Robinson, 1998, Rodriguiz et al., 2004, Muller et al., 2009, Stagkourakis et al., 2018, Boulanger-Bertolus et al., 2017, Lynch and Ryan, 2020, Chao et al., 2020, Josselyn et al., 2005, Ng et al., 2018, Sangha et al., 2013).

Our results showing a lasting increase in BLA dopamine following shock with the mother are in line with recent work in adult rats demonstrating that dopaminergic VTA neurons projecting to the BLA respond to aversive shock cues (Tang et al., 2020). Consistent with this, infant rats also have an increased dopamine response to acute shock, however, in contrast to adults, pups shocked in the presence of the mother show a dopamine decrease (Barr et al., 2009). Here we show that chronic social adversity disrupts this system, with repeated shock with the mother producing an increase in dopamine (Figure 5B). This elevated infant dopamine has been consistently linked with dopamine decreases in later-life, as observed in myriad psychiatric disorders and addiction (Dejean et al., 2013, Koob and Volkow, 2010, Nestler and Lüscher, 2019 Volkow et al., 2017, Wise and Robble, 2020, Menezes et al., 2021, Yu et al., 2014, Grace, 2016). These results also fit with work in humans showing that elevated dopamine levels play a role in social deficits observed in children with ASD (Pavăl, 2017) and that dopamine levels in the amygdala positively correlate with aversive processing the amygdala-anterior cingulate circuit (Kienast et al., 2008).

Interestingly, we observed a suppression of c-Fos expression in the CeA of adversity-reared pups, a highly GABA-ergic nucleus. This reversal is consistent with recent work from our lab showing that adversity is associated with increased volume and neurogenesis in the CeA, while these measures are decreased in the BLA (Raineki et al., 2019). Because we observed that adversity increases functional engagement of principal neurons in the BLA (Figure 1F) and because silencing the VTA-CeA circuit has no effect on aversive cue processing (Tang et al., 2020), we focused our circuit assessments on the BLA. Although two primary sources of DA to the BLA are the VTA and SNc (for review, see (Lammel et al., 2014, Morales and Margolis, 2017, Brinley-Reed and McDonald, 1999), we focus on the VTA as this region preferentially innervates the BLA (Tang et al., 2020, Lutas et al., 2019) and these projections are causally involved in social behavior (Gunaydin et al., 2014), processing aversive and appetitive stimuli (Tang et al., 2020, Lutas et al., 2019) and maternal regulation of the infant (Robinson-Drummer et al., 2019). Developmental research has shown that these VTA-BLA circuits are present by PN14 (Luo and Huang, 2016). Most importantly, however, despite other potential sources of DA to the BLA, and the fact that the VTA projects to places other than the BLA, our data definitively demonstrate that the VTA-BLA connection is necessary and sufficient to account for our behavioral changes.

In summary, the current results highlight a specific neural circuit that is necessary and sufficient for perturbing social behavior in adversity-reared pups. Within the context of caregiver regulation, we observed that repeated adversity with the mother is associated with elevated dopamine release in the BLA. Using optogenetics adapted for the very young behaving infant rat, we show that dopamine release in the BLA bidirectionally controls social approach toward the mother and peers. The major significance of our work is that it provides evidence for a specific circuit linking adversity, altered processing of the caregiver, and lasting social deficits. This may represent one way in which adversity initiates an aberrant developmental trajectory associated with amygdala deficits and social behavior, although many others are likely to coexist.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Regina Sullivan (regina.sullivan@nyumc.org).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Subjects

Male and female Long-Evans rats born and bred at Nathan Kline Institute (originally from Harlan Laboratories) were used as subjects. They were housed in polypropylene cages (34 × 29 × 17 cm) with wood shavings, in a 20 ± 1°C environment on a 12 h light/dark cycle. The day of birth was considered PN0, and litters were culled to 12 pups (6 males, 6 females) on PN1. Food and water were available ad libitum. Only one male and/or one female were used from each litter per experimental group. Unless noted otherwise, all experimental groups included at least 8 subjects (equal male and female). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nathan Kline Institute and New York University, in accordance with guidelines from the National Institutes of Health.

METHOD DETAILS

Adversity treatments

Scarcity-Adversity rearing

All pups experienced typical rearing until PN8 and again after PN12. At PN8, half of the litters were randomly assigned to the Scarcity-Adversity rearing, where cage bedding was reduced to a 1.2 cm layer nesting/bedding material from PN8–12. These ages were selected based on previous research from our laboratory and others that suggested experiencing adversity during this age range produces enduring neurobehavioral effects across development (Upton and Sullivan, 2010, Raineki et al., 2010, Roth and Sullivan, 2005, Walker et al., 2017).

This limited bedding environment decreased mothers’ ability to construct a nest, which resulted in frequent nest building, rough handling, and stepping on pups (see Table S1). This procedure does not alter pup body weight at any age, including PN13 (t(8) = 0.100, p = 0.923) but increases corticosterone levels in response to a mother-pup social behavior test (t(6) = 6.950, p < 0.05) (Roth and Sullivan, 2005, Raineki et al., 2010). Control litters continued to have typical rearing with 5–7 cm layer nesting/bedding material throughout development. All cages were cleaned at least twice a week throughout development, including during the reduced bedding procedure. Maternal and pup behaviors were scored daily during the experimental manipulations for all litters.

Shock with Mom procedure: single infant shock experience with and without maternal presence

Infant PN12 rat pups were assigned to one of 3 treatment groups: shock alone (“Shock”), shock with maternal presence (“Shock w/ Mom”) or control (“control”). Pups were removed from the nest and placed in Plexiglas containers either with or without an anesthetized mother. The mother was anesthetized with Urethane, which prevents the milk ejection reflex; thus pups did not receive milk. Pups without the mother were placed in beakers and kept warm through ambient heated air designed to keep body temperature thermoneutral. Following a 10-min acclimation period to recover from experimental handling, pups designated to receive shock had 9 presentations of a 1 s 0.5mA tail shock, each shock separated by a 4 min interval. Other pups from the same litter were treated identically except that the anesthetized mother was present. A non-shock, no mother group that was removed from the nest and placed in beakers, as were the experimental groups, served as normal controls. During the infant sessions ultrasonic vocalizations (USV) and behavioral activation to the shock were assessed in the infants (Day et al., 2007, Hofer and Shair, 1978). Behavioral activation was assessed using automatic measurement of pixel changes (NOLDUS Ethovision) and manual counting of limb movements (5 = all four limbs plus head) in response to each shock presentation (Santiago et al., 2018, Lewin et al., 2019). Following treatment, all pups were returned to the nest or placed in an incubator for 1 hour until euthanized followed by brain removal. For c-Fos studies the brains were perfused or rapidly frozen and subsequently sectioned on a cryostat for further processing.

Repeated infant treatment

Separate groups of pups received the same treatment described above, except the procedure occurred daily from age PN8–12 with or without the mother present (every 5 mins, 18 shocks total). We included a no-shock, no-mother control group, and a no-shock mother control group. Pups show approach and attachment behaviors toward any nursing dam with the same diet as their biological mother (i.e., same diet-dependent maternal odor, (Galef and Kaner, 1980, Raineki et al., 2015, Sullivan et al., 1990), and therefore the biological mother does not need to be disturbed. This procedure does not produce conditioned aversion toward the maternal odor (Figure S3). Care is taken to ensure that when pups are returned to the nest, the mother is not disturbed and pups approach dam readily (Figure S2). Furthermore, all treatment groups are represented in each litter.

Pup behavior measures

Ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs)

Similar to human crying, infant USV is a measure of pup distress, and serves an important communicative role in eliciting caregiving behaviors (Hofer and Shair, 1978). In this structured assessment of infant USVs outside of the nest, USVs were recorded while pups underwent the Shock with Mom procedure (pups either with mom, shocked while alone in a beaker, or alone in a beaker with no shock), with all testing occurring in a temperature-regulated room (32.8°C) by an experimenter blind to experimental conditions. The mother was anesthetized with Urethane (2 g/kg, i.p.), and placed with her abdomen against the bottom and side of the testing cage to prevent the possibility of pups attaching to her nipples during the test (Hofer and Shair, 1978). All recordings were made following a 1-min habituation period, using an Ultramic 200k USB microphone (Dodotronic), with a 200-kHz sampling rate, and USVs were visualized using SeaWave (CIBRA) software. Spectral analysis of USV data was performed using the Spectral Analysis Toolbox from the open source code repository Chronux (chronux.org). The code was implemented using MATLAB (MathWorks) and utilized a moving window, multi-taper spectral analysis. A detailed description and validation of these specific procedures is provided elsewhere (Bokil et al., 2010). Moving windows were set to 300 ms and 100 ms. Sampling frequency of the USV data was 200 kHz, meaning that the Nyquist frequency of the computation (100 kHz) was well above the target frequency band of 30–60 kHz, which is the frequency at which pups elicit “distress” calls, such as when socially isolated (Cacioppo et al., 2011, Insel et al., 1986). Following computation of the spectral analysis, data in the 30-to 60-kHz band were isolated during the second minute of data recording under all four conditions. Total spectral power in the frequency band was calculated in decibels (dB). The mother’s ability to reduce infant USV emission was calculated as the percent reduction of USV power (dB) from the socially isolated condition to the anesthetized mother condition ([dB alone – dB with mom] / dB alone). All recordings and data processing were conducted by experimenters blind to rearing conditions.

Mother-pup social behavior test

At PN13, pups received a 30 min social behavior test with a Urethane-anesthetized mother (milk letdown blocked) placed on her side to give pups access to nipples. We used an anesthetized mother to eliminate the impact of maternal behavior, which can obscure pup behavioral competence and deficits. Pups were individually placed with the mother and permitted to freely interact with the mother. Tests were recorded and scored blind to experimental condition. Behaviors observed included: time nipple-attached, time at mother’s ventrum (not nursing), going behind the mother’s back, and stereotyped behaviors such as pivoting, climbing or pushing mom, and treading (movement of all four limbs in a ‘swimming’ fashion while probing mom’s ventrum with nose). Instances of these behaviors were counted over the course of the test and total instances per animal was used as a measure “atypical attachment behaviors.” The biological mother or a mother of similar postpartum age was used as the anesthetized mother for treatment and testing. As described above, pups will orient toward a dam and nipple attach if her diet is the same as the diet fed to the biological mother (Galef and Kaner, 1980, Raineki et al., 2015, Sullivan et al., 1990).

Weanling social behavior tests

Separate cohorts were tested at 22 ± 1 days of age for social behavior (weaned at PN21), using an adaptation of the Crawley 3 chamber social test apparatus (Crawley, 2004). Animals were given a 5-min acclimation, followed by placement of a novel peer and littermate into two perforated metal boxes (15×15 cm) in each of the outside chambers. The test animal (same age and sex as target) was then given a 10-min test and time spent in each chamber, the duration of nose contact with target animal and activity level were recorded and automatically analyzed using the Noldus Ethovision XT system (Noldus et al., 2001). Videos were validated by hand-scoring using BORIS software (Friard and Gamba, 2016). Peers were the same sex as the subject. Peers were observed for stress responses, including freezing, hyperactivity and hypervigilance and there was no evidence they were stressed. This is consistent with previous studies showing that neither stimuli nor experimental animals emit USVs in the three-chamber test (Opendak et al., 2016) and habituation to the chamber before testing prevents additional stress effects (Yang et al., 2011).

Corticosterone radioimmunoassay

Sixty min after the final treatment, pups were decapitated and trunk blood collected and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 6 min. Serum was stored at –70°C until radioimmunoassay was performed. Duplicate serum samples were analyzed for corticosterone using the Rat Corticosterone RIA Kit (MP Biomedicals; sensitivity 5 ng/mL, RRID:AB_2783720).

General infant craniotomy procedure

Specific details for each manipulation are described in sections below. Basic procedures are as follows: Pups are removed from the nest without disturbing the mother and placed partially on a surgical heating pad to permit behavioral thermoregulation. No more than 6 pups from a litter are used to minimize stress to the mother. Before surgery, pups are anesthetized by inhalation with isoflurane and placed in an adult stereotaxic apparatus modified for use with infants. During aseptic survival surgery, visual inspection of skin color, motor tone and respiration are continuously performed to monitor for signs of distress or waking. Following the implant/infusion, the incision is stitched with 2–3 sutures and Nailbiter (bitter tasting product to discourage nail biting) is applied to the incision to discourage the mother from biting the surgical area. Following a 30 min recovery and regaining of righting reflex, pups are returned to the nest until experimental procedures. One day of recovery is sufficient for pups up to weaning age. Pups are anesthetized for < 20 min and are not away from the mother > 60 min (Opendak et al., 2020, Boulanger Bertolus et al., 2014, Moriceau and Sullivan, 2004, Raineki et al., 2010, Roth and Sullivan, 2005, Shionoya et al., 2006).

Ensuring pups thrive after surgery

Following all surgical procedures on pups for this project, pups and mothers were inspected after pups were returned to the nest. Inspection was to ensure pups were not rejected and were able to thrive, i.e., presence of milk band and typical behavior, based on published procedures from the Sullivan lab (Opendak et al., 2020, Barr et al., 2009, Raineki et al., 2019, Al Aïn et al., 2017, Roth and Sullivan, 2006, Sarro et al., 2014, Sullivan et al., 2000, Sullivan et al., 1994). Before being returned to the nest, experimenters ensured pups were fully recovered from anesthesia and were mobile and responsive to tactile stimulation and were behaviorally indistinguishable from unsurgerized pups. All removals and returns to the nest were < 1 min by trained experimenters to ensure minimal disruption for the dam. Dam behavior was inspected for the following atypical behaviors: rough handling, dragging pups, and rejecting the surgerized pups. The animals are euthanized if they present: 1) failure to gain weight, or 2) animal fails to respond normally during the preparation for the experiment. For example, vocalizations while being handled or being connected to the fiber optic cables indicates the animal did not recover well after surgery. Over the course of the study, fewer than 10 pups were euthanized for these reasons.

Tissue processing

Amygdala Dissections

Rats were sacrificed by decapitation immediately after the last treatment. To assess protein expression, amygdalae were dissected using standard techniques, frozen on dry ice and stored at –80°C until biochemistry.

Tissue Preparation

Fractionation.

Amygdalae were micro-dissected and prepared into cytosolic and synaptic fractions. Tissue was homogenized in a TEE (Tris 50 mM; EDTA 1 mM; EGTA 1 mM) buffer containing a SigmaFast, protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich). Tissues were homogenized in 200 mL of the TEE-homogenization buffer using 20 pumps with a motorized pestle. Homogenates were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 3,000 g (5 min at 4°C), to remove unhomogenized tissue. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 30 min. After ultracentrifugation, the supernatant was collected and stored as the cytosolic fraction. The remaining pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of homogenizing TEE buffer containing 0.001% Triton X-100, incubated on ice for 1 hr and then centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 hr at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 50 μL of TEE buffer and stored as the synaptic fraction. The Pierce bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to determine protein concentration for each sample. Samples were reduced with 4× Laemmli sample buffer equivalent to 25% of the total volume of the sample and then boiled and stored frozen at –80°C.

Western blot analysis

Samples (20 μg) were loaded onto a Tris/Gly 4%–20% midi gel to resolve TH (60 kDa, polyclonal anti-rabbit, 1:1000, Cat No. 657012, EMD Millipore, Burlington MA USA, RRID: AB_10000323), D1 (50 kDa, polyclonal anti-rabbit, 1:1000, Cat No. ab20066, Abcam, Cambridge UK, RRID: AB_445306) and D2 (50 kDa, polyclonal anti-rabbit, 1:1000, Cat No. ab5084p, EMD Millipore, Burlington MA USA, RRID:AB_2094980). Antibodies against GAPDH (1:5000, monoclonal, Cat No. mab374, EMD Millipore, Burlington MA USA, RRID:AB_2107445) were used to estimate the total amount of proteins. Every gel contained 1–3 lanes loaded with the same control sample designated as all brain sample (ABS). ABS was used to standardize protein signals between gels. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes in IBlot® Dry Blotting System (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) for 9 min. Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated in blocking solution containing 5% sucrose in Tris Buffered Saline with Tween-20 (TBST; 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight in primary antibodies and then probed with Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibody. Membranes were incubated with Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate and exposed on CL-XPosure Film (Thermo Scientific; Rockford, IL). Films were scanned for quantification with NIH ImageJ. The amount of each protein was normalized for the amount of the corresponding α-tubulin detected in the sample. Group values are expressed as a percentage of a selected group average pixel density.

c-Fos immunohistochemistry

Sixty min after the 30 min mother-pup social behavior brains were removed and processed using a standard c-Fos staining. Briefly, brains were sliced into 20 μm coronal sections and mounted on slides. After 1 hour of postfix in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (PB) (pH 7.2) each slide was rinsed in PB (pH 7.2) and dried by cool airstream. To eliminate peroxidase activity, sections were incubated in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) containing 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 10% methanol for 5 min. Following PBS rinses and 15 min incubation in 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri), slides were incubated in 3% Bovine Serum Albumin (Sigma) for 1 hour. After additional PBS rinses, slides were treated overnight at 4°C with the primary anti-body (c-Fos, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-52, RRID:AB_2106783) diluted 1:500 in PBS. was added (Afterward, they were rinsed in PBS, incubated in the secondary biotinylated antibody (goat anti-rabbit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California) for 2 hours at room temperature, and then incubated for 90 min in avidin-biotin-peroxidase (ABC) complex solution. Slides were then treated with PB containing 0.1% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and H2O2 and dehydrated in alcohol and Histoclear (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Georgia) followed by coverslipping for microscope examination. A microscope equipped with a drawing tube (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan; 10 X objectives) was used to count c-Fos-positive cells. Brains were outlined delineating the amygdala (BLA, CoA, MeA, and CeA). All c-Fos cells were counted without prior knowledge of treatment and were distinguished from background based on density of staining, shape and size of the cell. The mean number of c-Fos positive cells per brain area was determined by averaging the bilateral cell count from all sections (three sections per brain).

c-Fos/CamKII double-labeling

Separate groups were analyzed for c-Fos/CamKII double-labeling after social behavior. For these groups, brains were collected as above and sections were rinsed with PBS-Triton. Anti-c-Fos primary antibody (polyclonal guinea pig, 1:1000, cat no 226 005, Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany, RRID:AB_2800522) and Anti-CamKII primary antibody (polyclonal rabbit, 1:1000, cat no AB52476, Abcam, RRID: AB868641) in blocking solution, was added and incubated overnight. The sections were then washed with PBS and a polyclonal goat anti-guinea pig secondary antibody (Alexa 488, 1:1000, Abcam, cat no 150185, RRID:AB_2736871) and VectaFluor RTU DyLight 594 horse anti-rabbit IgG (Vector, Cat no DI-1794–15, RRID:AB_2336784). Sections were then washed with PBS. Finally, sections were placed on glass slides, mounted using DAPI-fluoromount G (Southern Biotech) and sealed with nail polish. Epifluorescent and confocal microscopy were used to take pictures of the sections in amygdala. Photos were imaged from each brain using a Zeiss Axiovert confocal laser scanning microscope (510 LSM; argon 458/488nm and helium−neon 543 nm). Images were then analyzed using ImageJ software. For each rat, three sections containing the BLA per hemisphere were imaged and analyzed. Double-labeling was measured using z stacks of 10 1um thick optical sections in the BLA.

TH expression comparison

TH expression was measured for mean optical intensity using sections of the VTA and BLA. For these analyses, the VTA/BLA within a single hemisection was imaged in its entirety, with 10 images obtained for each hemisection. Photos were imaged and measured for intensity from each brain using a Zeiss Axiovert confocal laser scanning microscope (510 LSM; argon 458/488nm and helium−neon 543 nm). Using ImageJ, raw region of interest (ROI) intensity values were divided by caudate putamen intensity values within the same pixel-size.

Microdialysis / HPLC procedures

Two days before treatment, pups were anesthetized (isoflurane) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus adapted for infant rats. Plastic guide cannulae (CMA987076, CMA Microdialysis, Sweden) were implanted unilaterally (caudal −0.90mm; lateral ± 4.50mm from bregma; lowered 6.0mm) aimed at the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala through a hole drilled in the overlying skull. Following recovery from surgery (approximately 30 to 60 min), pups were returned to the nest. On the day of the experiment, pups were placed in a 27cm diameter acrylic circular cage (EICOM corp., Kyoto, Japan) and were able to move freely. The microdialysis probe (CMA986075, 9mm length, 1mm membrane; CMA/Microdialysis, Sweden) was inserted into the guide cannula 20 min before collection. The probes were perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 147mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 1.2mM CaCl2, 0.85mM MgCl2) at a flow rate of 1.5 μl/min. Dialysate was collected automatically every 10 min in a refrigerated (4°C) microfraction collector (BASI Inc., USA) in which every vial contained 2 μL of 12.5mM perchloric acid/ 250 μM EDTA. After completion of the experiment, dialysate samples were immediately stored at −80°C until HPLC analysis.

Samples were analyzed using an Antec high-pressure liquid chromatography system with electrochemical detection (HPLC-ED) equipped to detect monoamines (Antec Scientific, Zoeterwoude, Netherlands). Samples were loaded into a 50 μl sample loop and injected, using an AS-110 autosampler, onto an analytical column (BDS Hypersil C18, 3mm,23150 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with a mobile phase consisting of 85 mM phosphoric acid, 29.2 mg/l, EDTA 596 mg/L KCL, 130 mg/L OSA, and 10% methanol at pH 6.0. Mobile phase was delivered via an LC-110 pump coupled with an OR-110 online degasser and pulse dampener. DA was detected using a Decade II electrochemical detector equipped with a VT-03 cell 0.7 mm GC ISAAC flow cell set at a current of 350 mV and a sensitivity of 100 pA. Output from the detector was analyzed with a computer program (Clarity, Data Apex, Prague, The Czech Republic) and levels were determined by comparison with a standard curve. The lower sensitivity limit for DA was approximately 0.1 nM. Machine sensitivity was confirmed throughout neurochemical analyses by injecting a neurochemical standard mixture every fifth sample to ensure proper calibration.

Pharmacological manipulations

Amygdala dopamine/receptor antagonist infusion

At 6-days-old, pups were anesthetized by inhalation with isoflurane and placed in an adult stereotaxic apparatus modified for use with infants. Stainless steel cannulas (30-gauge tubing) were implanted bilaterally in the amygdaloid complex through holes drilled in the overlying skull. The bilateral cannulae were implanted (caudal 0.80mm; lateral ± 3.00mm from bregma, lowered 5.0mm from skull surface) and fixed to the skull with dental cement. To ensure cannula patency, guide wires were placed in the lumen of the tubing and Nailbiter (bitter tasting product to discourage nail biting) was applied to the pup’s cannula to discourage the mother from biting the surgical area. Following a 30 min recovery, the pup was returned to the nest until experimental procedures across PN8–12.

Pup were placed either alone in beakers or with the mom and electrodes attached to the base of the tail. Their bilateral cannulae were attached via PE10 tubing to a Harvard syringe pump driving two Hamilton microliter syringes. The cannulae were filled (16 s at 0.5 μl/min) with either a dopamine receptor antagonist (cis-(Z)-flupenthixol dihydrochloride (20 μg, Sigma), dopamine (6 μg, Sigma) or saline. During the first 20 min of the conditioning period, pups received drug or control solution infused at 0.1 μl/min, for a total infusion volume of 2.0 μL as previously described (Barr et al., 2009). Procedures were based on previous work using DA infusions into BLA from our lab and others (Barr et al., 2009, Di Ciano and Everitt, 2004, Lalumiere and McGaugh, 2005). We verify this manipulation through histological techniques but also through documentation of spread. This is done through infusion of a radioactive drugs in an awake animal that duplicate the procedures used to gather behavioral data in pups with a brain cannula. After the behavior test, the brain are removed and processed using auto-radiography and STORM. Following conditioning, pups were disconnected from the syringe pump and returned to the nest until testing, the following day.

Systemic dopamine manipulation

Separate cohorts of pups received intraperitoneal injections of the dopamine receptor antagonist cis-z-flupenthixol (0.3 mg/kg, Sigma) or an equal volume of 0.9% saline. Drug administration occurred 30 mins before the daily shock-mom procedure outside the nest from PN8–12. Dosage was based on previous studies in adult rats (Engster et al., 2015, McDougall and Bolanos, 1995) and piloting, i.e., drug-injected pups were indistinguishable from vehicle-injected pups during experimental preparation.

Histological verification of cannula/probe placement

Following microdialysis experiments or after testing following amygdala infusion, pups’ brains were removed, frozen and sectioned at 20 μm using a −20°C cryostat. Sections were stained with cresyl violet for identification of the microdialysis probes and cannula placement in relation to the amygdala using a neonatal atlas.

Infant optogenetics

Surgery