Abstract

The endoplasmic reticulum, a vast reticular membranous network from the nuclear envelope to the plasma membrane responsible for the synthesis, maturation, and trafficking of a wide range of proteins, is considerably sensitive to changes in its luminal homeostasis. The loss of ER luminal homeostasis leads to abnormalities referred to as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Thus, the cell activates an adaptive response known as the unfolded protein response (UPR), a mechanism to stabilize ER homeostasis under severe environmental conditions. ER stress has recently been postulated as a disease research breakthrough due to its significant role in multiple vital cellular functions. This has caused numerous reports that ER stress-induced cell dysfunction has been implicated as an essential contributor to the occurrence and development of many diseases, resulting in them targeting the relief of ER stress. This review aims to outline the multiple molecular mechanisms of ER stress that can elucidate ER as an expansive, membrane-enclosed organelle playing a crucial role in numerous cellular functions with evident changes of several cells encountering ER stress. Alongside, we mainly focused on the therapeutic potential of ER stress inhibition in gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer. To conclude, we reviewed advanced research and highlighted future treatment strategies of ER stress-associated conditions.

Keywords: endoplasmic reticulum stress, unfolded protein response, cell death, colon cancer, treatment target, inflammatory bowel disease

1 Introduction

Due to the “lace-like” characteristics of the reticulum in the ground substance of cells grown in tissue culture by electron microscope (Qi and Chen, 2019) along with its closeness to the medial side of the cytoplasm, in 1945, the name endoplasmic reticulum was given (Porter and Thompson, 1948; Porter and Kallman, 1952). A cystic, vesicular, and tubular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is part of the ER structure-derived membranous compartments and forms a continuous omentum system containing almost all eukaryotic cells. Along with that, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the primary organelle responsible for regulating transmembrane and soluble secretory proteins processing, folding, assembly, modification, and lipid biosynthesis. This is also an organelle responsible for most transmembrane for its crowded membranous structures. Koch et al. (1986) discovered evidence for the most abundant calcium-binding glycoprotein located in ER for the first time of progression, suggesting that the major role of ER in vivo involves intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis.

Surprisingly, many studies have shown that cell stress response is linked to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. The following experimental results supported this inference. First, ER dilated when faced with stresses such as heat (Chrispeels and Greenwood, 1987), dehydration (de la Pena de Torres, 1978), water overloading (de la Pena de Torres, 1978), fasting, cortisol injections, reserpine injections, restraint, spinal cord transaction, immersion in hot water, exposure to cold, and forced muscular exercise in a revolving drum (Salas et al., 1980). In addition, it has been discovered that many genes encode proteins located in ER, including the 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein GRP78 (also called BiP for binding immunoglobulin protein), the 94-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP94/ERp99), and ERp72, and some of the members of the stress protein family listed above have been increased in stress condition by a range of bioinformatic methods (Collins and Hightower, 1982; Welch et al., 1983; Lee et al., 1984). As countless investigations corroborated, the Hsp70 chaperone GRP78 works in concert to ensure the correct folding of proteins targeted for extracellular secretion (Haas and Wabl, 1983; Pelham, 1986), as well as binding proteins without being correctly folded and assembled to lead them to degradation pathways within the ER (Ng et al., 1990; Gething and Sambrook, 1992). When cells respond to turbulence from both internal and external environments, the function of ER that transfers transmembrane proteins and maturation of most secreted posttranslational modifications proteins molecules to cytoplasm will not work. This results in the ER becoming paralyzed due to the accumulation of folded/unfolded proteins. Then, the unfolded protein response (UPR) activates, resulting in a complex cellular response including the upregulation of abnormal protein degradation in the ER, with the goal of resolving the ER stress subsequently.

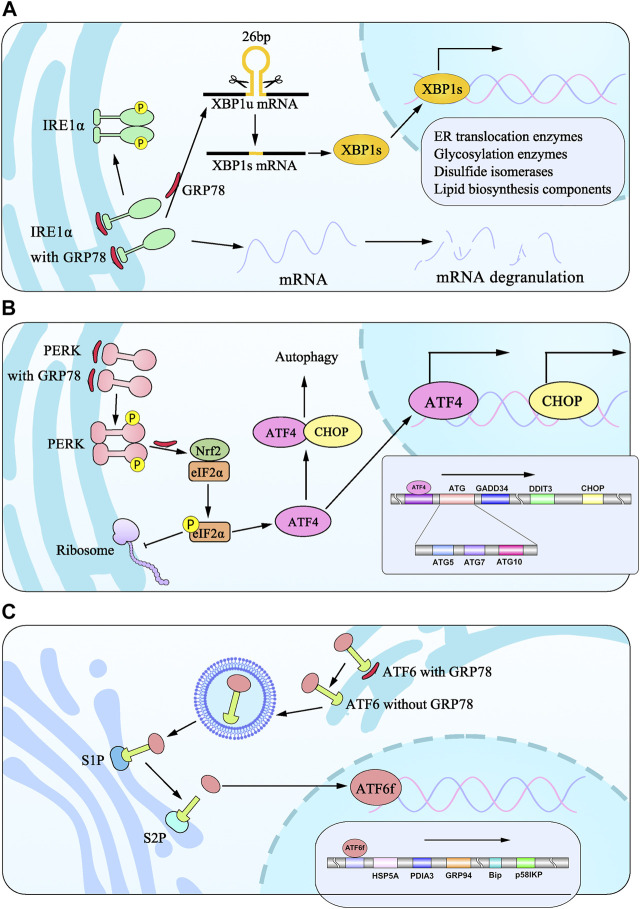

Served as three main sensors of UPR with the responsibility for transmitting messages to the rest of cells (Ron and Walter, 2007), the serine/threonine-protein kinase/endoribonuclease inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) are crucial ER-resident transmembrane proteins. It is universally acknowledged that UPR is an integrated ER stress response pathway coordinated by three distinct pathways: the IRE-XBP1, the PERK-eIF2ɑ-ATF4, and the ATF6 pathway. The IRE/XBP1 pathway is the most conserved branch of the UPR, which facilitates the synthesis of ER chaperones to directly support ER protein folding (Lee et al., 2003b). The second one is the PERK-eIF2ɑ-ATF4 pathway, which suppresses translation to reduce the burden of ER (Harding et al., 1999). Lastly, ATF6 is a cryptic transcription factor entering the nucleus to upregulate target genes encoding chaperones transcriptionally.

To summarize, cells respond to misfolded proteins via three arms of the UPR. However, under conditions of sustained activation of ER stress state, the UPR switches modes from pro-survival to pro-apoptosis (Lu et al., 2014). As ER stressors themselves can cause cell death, such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, autophagy-dependent death, autophagy, and necrosis, they have attracted the attention of notable scientists. Therefore, this study aims to review current discoveries on ER stress and further analyze the correlation between ER stress and intestinal diseases to find a novel breakthrough point and therapeutic targets in ER stress-correlative-associated gastrointestinal disorders.

2 ER Stress and Its Overview

It is established that various exogenous and endogenous stresses such as hypoxia, starvation, infections, calcium depletion, acidosis, hyperglycemia, intoxication (Todd et al., 2008; Hetz, 2012), oxidized lipids, pathogen infection (Ye et al., 2011), salt stress (Liu et al., 2007), and heat stress (Liu and Howell, 2010), can evoke ER stress. Recent studies indicate that endogenous changes from cellular differentiation to profound metabolic induce the perturbations in ER function, which results from the accumulation of unfolded and misfolded proteins in the ER and triggers the unfolded protein response, also known as ER stress (Bettigole and Glimcher, 2015). From this, ER stress will initiate endoplasmic reticulum-related reactions by inducing a coordinated response, for instance, unfolded protein response (UPR), endoplasmic reticulum overload response (EOR), and sterol regulation reaction. The response mentioned above belongs to a protective counter-measure that reestablish homeostatic balance and promote survival by eliminating chronically misfolded protein or incorrectly folded proteins (Sitia and Braakman, 2003; Walter and Ron, 2011).

We initially summarized that ER stress responses are complex, involve multiple tissues and organs, and include corresponding functional changes. Thus, we addressed related UPR issues in this study. With the accumulation of unfolded and misfolded protein, UPR will be performed to restore homeostasis (Iurlaro and Munoz-Pinedo, 2016) by alleviating the burden of accumulated global protein synthesis and upregulating the ER-associated protein degradation (Ma and Hendershot, 2002; Todd et al., 2008).

3 ER Stress and Its Molecular Mechanism of Signaling Pathway

Herein, we summarize the active role played by ER stress in three signaling pathways and its mechanism of action in regulating these signaling molecules. The concept of ER stress being linked to dysfunctions of tissues and cells is generally accepted. So far, there are three crucial sensors: PERK (Ohoka et al., 2005), IRE1(Urano et al., 2000; Kouroku et al., 2007), and ATF6. They are activated and have been recognized in the UPR process. Under the physiological state, ER stress sensors are maintained in an inactive condition within the ER membrane through association with the chaperone protein, glucose-regulated protein 94 (Grp97), and GRP78 (Hamman et al., 1998; Malhotra and Kaufman, 2007; Tabas and Ron, 2011). The chaperone, GRP78, is one of the most abundant proteins within the ER that can enter the ER lumen, bind to a large variety of nascent polypeptides, and facilitate their translational folding correctly (Mori, 2000). Because unfolded substrates are more prone to bind GRP78 than the sensors, once ER stress is triggered, GRP78 will be sequestrated by the unfolded substrates to initiate UPR signaling. UPR signaling is a major pathway whereby cells respond to ER stress to reduce the synthesis of the general protein and restore new protein homeostasis (Clarke et al., 2014).

3.1 Biological Characteristic of IRE1

Cells harbor surveillance mechanisms to monitor protein-folding status and elicit adaptive responses to adjust protein-folding capacity. In other words, this mechanism of targeting protein quality control substrates expands the code that cells utilize to recognize aberrant proteins as it senses the state of translation rather than the folding state of the nascent chain. IRE1 belongs to type I transmembrane proteins kinase inositol-requiring enzyme 1, is the most evolutionary conserved among the sensors, remarkably exhibits similar mechanistic aspects shared between yeast and mammals, and has two paralogues encoded by nucleus signaling 1 and 2 (ERN1 and ERN2), respectively (Tirasophon et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1998; Iwawaki et al., 2001), IRE1α and IRE1β, in mammals. Structurally, the IRE1 can be divided into the three sub-compartments: an N-terminal luminal domain, a single-pass transmembrane spanning segment, and a cytosolic region subdivided into a Ser/Thr protein kinase domain (Tirasophon et al., 1998; Walter and Ron, 2011) and C-terminal endoribonuclease (RNase) domain (Hollien and Weissman, 2006). IRE1α was found and served as a positive control for detecting a functionally related ER-resident protein. Nonetheless, IRE1β was detectable by immunoblot of lysates prepared from purified microsomes from the small intestine, establishing specifically expressed in digestive tissues. And its switching components play a great part in pro-survival and pro-cell death signaling complexes. IRE1α regulates the dynamic signaling of the UPR. After accumulating unfolded or misfolded proteins in cells, IRE1α dissociates from GRP78, triggering IRE1α’s dimerization and trans-autophosphorylation mechanisms (Iurlaro and Munoz-Pinedo, 2016). Current evidence indicates that the oligomerization is crucial for IRE1 activation as it allows for trans-autophosphorylation and allosteric activation of its RNase domain by binding of ATP or ADP in the active site of the kinase. Upon activation, IRE1α cleaves the 26 pairs of base-pair fragments from mRNA of encoding the transcription factor X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), resulting in the unspliced XBP1 (XBP1u) forming spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) that encodes a wide variety of UPR target genes (Sidrauski and Walter, 1997; Yoshida et al., 2001; Meyerovich et al., 2016). XBP1u is a short-lived protein that is rapidly degraded by proteasomes (Lee et al., 2003a). On account of a basic leucine region zipper (bZIP) transcription factor, XBP1s are able to control protein folding, secretion, and phospholipid synthesis. With the regulation of ER chaperone protein-coding, XBP1s is a member of protein degradation in ER cavity (Park et al., 2017) and is commonly used as a readout of UPR activation (Campbell et al., 2013).

Noting this, activation of the IRE1/XBP1 pathway, the most conserved branch of the UPR, can upregulate the expression of ER translocation enzymes, glycosylation enzymes, disulfide isomerases, and boost transcriptionally genes involved in lipid biosynthesis components, whereby protein synthesis and accumulation in the ER cavity can be effectively reduced. Specifically, under the condition of severe ER stress, the IRE1 endonuclease activity can also degrade mRNAs (Hollien and Weissman, 2006; Hollien et al., 2009), thereby providing a way to reduce ER overload and playing a paramount role in regulated IRE1-dependent mRNA decay (RIDD). Hollien and Weissman (2006) reported that it is likely to produce additional insights into the biological outcomes of ER stress beyond the simple degradation of unwanted mRNAs. Moreover, overexpression of IRE can lead to cleavage of 28S rRNA (Iwawaki et al., 2001). Contrary to previous evidence, Jeffery S and his colleagues unambiguously confirmed that the IRE1 function is required to protect cells from ER stress. In addition, they also established that IRE1−/− are prone to death from administrated tunicamycin (TM) or β-mercaptoethanol, autophagy-inducing agents, which can lead to accumulation of unfolded proteins in the JC103 and CS165 cultures growing in the middle phase (Cox et al., 1993). It is worthy of noting that Jonathan H. Lin et al. demonstrated that human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells pretreated with TM or thapsigargin (TG) (the SERCA ATPase sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases inhibitor) exhibited ER stress with an evaluation of Xbp-1s mRNA level detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and its protein levels tested by western bolting, which indicated IRE1 activation. To further assess the effect of IRE, through selectively upregulating IRE1 activity by treating HEK293 cells with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) analog 4-amino-1-tert-butyl-3-(1′-naphthylmethyl) pyrazolo (Kim et al., 2020) pyrimidine (1NM-PP1), results indicated that the number of surviving cells is much higher (Lin et al., 2007). Furthermore, normal human colon epithelial cell line (NCM-460) cell viability was significantly reduced upon IRE-1 RNA interference. At the same time, overexpression of IRE-1 decreased cell apoptosis rate and rescued IL-6-induced cell apoptosis (Zhang B. et al., 2021). The above data all powerfully evidenced that IRE1 is responsible for promoting cell viability (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Model diagram of signaling pathways from three ER transmembrane stress sensors during UPR induced by ER stress. (A) IRE1α isolates from BiP undergo dimerization and phosphorylation to splice 26bp from XBP1 into XBP1s, which translocates to the nucleus and induces the transcription of target genes. (B) PERK signaling is initiated through PERK dimerization and autophosphorylation of the cytosolic PERK kinase domain. eIF2α phosphorylation is elicited to attenuate global protein synthesis. eIF2α promotes translation of ATF4, which translocates to the nucleus to regulate the expression of target genes and cooperates with CHOP to participate in ER stress-induced apoptosis pathways. (C) ATF6 dislocates from BiP translocates to Golgi apparatus, which is cleaved by proteases at S1P and S2P sites into ATF6f and promotes the transcription of genes.

3.2 PERK and Its Biological Properties

PERK is encoded by the perk gene that phosphorylates the α-subunit of eukaryotic translation-initiation factor 2 (EIF2S1/eIF-2α) in chromosome 2 p11.2 88556741–88627576. Also known as EIF2AK3, PERK belongs to serine/threonine-protein kinase, contains a distinctive amino-terminal region 550 residues in length, and possesses a similar structure to IRE1. It belongs to type I transmembrane protein (Shi et al., 1998; Harding et al., 1999; Bertolotti et al., 2000). Intriguingly, PERK binds to GRP78 via its N-terminal domain and dissociates depending upon forming its homodimers in case of ER stress. The C-terminal region is cytosolic and contains the kinase domain and autophosphorylation sites (Harding et al., 1999), activating the downstream signaling pathway (Kikuchi et al., 2016). PERK is a kinase occurring at Tyr615. Upon activation, PERK autophosphorylates (Su et al., 2008) and becomes able to efficiently phosphorylate eIF2α to attenuate transient global translation (Shi et al., 1998; Harding et al., 1999; Harding et al., 2000b). At length, the activated PERK triggers the transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), thereby inducing antioxidant proteins. It also binds to the eIF2α to promote eIF2α phosphorylation at the serine 51 residue, as Shi et al. reported in cell lines and Sprague–Dawley rats models. Aside from that, eIF2α also plays a pivotal role in the early steps of mRNA translation from nematodes to mammals through identifying PEK homologs belonging to Caenorhabditis elegans and pufferfish Fugu rubripes. In fact, eIF2α phosphorylation is essential for cell survival. Through the mutation of eIF2αphosphorylation at Ser51 on the α subunit, mutant eIF2α cells showed a larger protein synthesis and necrosis by flow cytometry than wild-type cells (Scheuner et al., 2001). It is attested that phosphorylation of eIF2α suppresses 80S ribosome assembly, attenuating protein synthesis and misfolded protein overload in ER (Pain, 1996; Cao et al., 2013). In conclusion, that summarizes the recent progress of research focusing on cell survival by reducing protein synthesis following ER stress. A detailed understanding of this mechanism can be seen in Figure 1B.

It is well known that multiple signaling pathways are involved in protein synthesis, and activation of the PERK pathway suppresses the production of the proteins under ER stress to restore cellular homeostasis. Numerous experimental studies have demonstrated that phosphorylation of eIF2α regulates translation of the ATF4 mRNA by activating multiple upstream open reading frames (Harding et al., 2000a; Lu et al., 2004; Vattem and Wek, 2004). ATF4, known as an efficiency transcription factor, induces the expression of antioxidant- and amino acid-related genes. It has been found to play a role in protein synthesis and secretion, such as DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 (DDIT3) DNA damage-inducible 34 (GADD34) (Harding et al., 2003; Han et al., 2013). DDIT3, as a trans-activator of transcription genes, can actively regulate apoptosis. It should also be noted that ATF4 and dephosphorylates eIF2α contribute to upregulating GADD34 identified as a participant for translational recovery (Novoa et al., 2001; Ron, 2002) (Box1). Alongside, the influence on phosphorylation of eIF2α and inhibition of mRNA translation is transient (Pavitt and Ron, 2012). Moreover, ATF4 induces a second transcription factor, C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP, also known as GADD153), which promotes autophagy as described in Box2.

3.2.1 Box 1 ATF4

ATF4 (activating transcription factor 4) belongs to the DNA-binding protein family of transcription factors, locates on chromosome 22 q13.1 39519695–39522685, and is highly regulated by eIF-2α/EIF2S1 phosphorylation. ATF4 is also an activator of the stress-responsive gene transcription factors, suggesting that the recovery of cellular function may be mediated by ATF4.

With the impact of ER stress, the expression of ATF4 is dependent on PERK activity and eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF4 level among perk −/− cells, and EIF2αS51A/S51A knock-in cells (which cannot be phosphorylated by eIF2α kinases). Along with that, cells overexpressing an eIF2α phosphatase have decreased significantly (Harding et al., 2000a; Novoa et al., 2001; Scheuner et al., 2001). Additionally, Atf4ΔIEC mice have developed spontaneous enterocolitis and colitis of greater severity than control mice after administration of DSS (Hu et al., 2019).

Apart from acting as a master transcriptional regulator of the ER stress, ATF4 regulates various genes, including those involved in amino acid transporters and cellular redox control genes (Harding et al., 2003).

It should also be noted that ATF4, a key transducer (Rutkowski and Hegde, 2010; Hetz, 2012), not only directly induces expression of GADD34, which further contributes to translational recovery and dephosphorylating eIF2α (Novoa et al., 2001; Ron, 2002), but also drives the transcription of genes involved in autophagy such as ATG genes, Atg7, Atg10, and Atg5 (B'Chir et al., 2013).

3.2.2 Box 2 CHOP and Its Functions

CHOP (C/EBP-homologous protein), also known as growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153), is highly expressed in the case of consecutive ER stress containing basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domains. bZIP is a transcription factor by which CHOP forms heterodimers with C/EBP family members (Ron and Habener, 1992; Wang et al., 1996).

CHOP regulates more than 200 genes encoding proteins promoting autophagy (Marciniak et al., 2004; Rouschop et al., 2010). Experimental evidence strongly tied to apoptosis induced by ER stress shows that CHOP −/− displays attenuated death induced by TM, TG, and A23187, of which the conclusion obtained from comparing cells periodically by phase-contrast microscopy of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) derived from chop−/− and chop+/+ genotypes (Zinszner et al., 1998). Recently, detailed investigations indicated that cell death apoptotic pathways induced by cell death-targeted treatment were not activated following the knockdown of CHOP (Dilly et al., 2020).

Mechanisms of CHOP-inducing apoptosis have been elucidated by focused studies on apoptosis-related genes, including apoptotic B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), GADD34, ER oxidoreductin 1 (ERO1ɑ), and tribbles-related protein 3 (TRB3) (Szegezdi et al., 2006). On the one hand, the levels of GADD34, a regulatory subunit of an eIF2α-specific phosphatase complex, can be mediated by CHOP via upregulating the transcription of ERO1α. This activates IP3R and promotes calcium release to mitochondria, thereby inducing cell apoptosis (Li et al., 2009; Xia et al., 2019). On the other hand, CHOP facilitates the expression of Bim that initiates the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, which realizes negative feedback on Bcl-2, playing a role in inhibiting mitochondrial outer membrane pore formation (McCullough et al., 2001). Intriguingly, ATF3, as one of the substrates of CHOP, can be coordinated to bind the promoter of the genes of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor 1/2 (TRAIL-R2/DR4/5), facilitating their expression to initiate activation executioner caspase-8 leading to cell death.

3.3 ATF6

Activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), a type II ER transmembrane protein with a molecular weight of 90 kDa, has two isoforms of proteins identified in mammalian cells: ATF6α and ATF6β (Han et al., 2013). Once ER stress occurs, ATF6 dissociates from GRP78, transfers to the Golgi apparatus, and is sheared into ATF6 fragments (ATFf) with an active N-terminal 50 kDa domain by site-1 protease (S1P) and site-2 protease (S2P), which possess the capacity for shearing in Golgi (Chen et al., 2002; Hong et al., 2004; Nadanaka et al., 2004; Shen et al., 2002). With the cytosolic basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor assistance, ATF6f can enter the nucleus through the nuclear membrane and regulate the transcription of the related genes involved in protein folding, such as HSP5A, PDIA3, GRP94, GRP78, and p58IPK (Kokame et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 1998). The detailed process is illustrated in Figure 1C. Apart from that, via binding to cAMP-responsive elements (CRE) and ER stress-response elements (ERSE-1), ATF6f is involved in the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway contributing to protein degradation (Yoshida et al., 2001; Chiang et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2018). Furthermore, ATF6 and PERK enhance the levels of CHOP expression, thereby leading to the induction of autophagy genes. Moreover, ATF6 is functionally crucial for the nucleation of autophagosomes, indicating that ATF6-mediated signaling plays a critical role in cell survival in response to ER stress (Szegezdi et al., 2006).

4 Cross Talk of Cell Death and ER Stress

Changes in cells’ fate after the impact of ER stress are diverse, depending on whether being mild, transient, or severe. Chances are alleviated to restore homeostasis if ER stress is mild or transient. In contrast, in the case of ER stress persisting overwhelmingly, cell manipulations may cause changes in gene expression or even cell death along with three parallel forms of cell death: apoptosis (Choi et al., 2019), pyroptosis (Ke et al., 2020), and autophagy (Kaser and Blumberg, 2010).

4.1 Apoptosis Induced by ER Stress

It is widely accepted that the fundamental pathways of UPR can trigger apoptosis in case of overwhelming ER stress. IRE-1α induces apoptosis by cleaving microRNAs regulating caspase-2 expression through the RNase activity (Hassler et al., 2012). Interestingly, perk −/−cells exhibit disturbed ER morphology and Ca2+ signaling and are feeble in the ER-mitochondria contact sites. Details shown in Box3 indicate that PERK is uniquely enriched at the mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) (Fan and Simmen, 2019). It has been reported that antioxidant coordinator Nrf2 is a target of the PERK kinase activity (Harding et al., 2003). However, given the relatively few studies involving this mechanism, it will be fascinating to unravel this challenging question. In addition, PERK is involved in mediating X-linked apoptosis inhibitor of protein (XIAP), a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family of proteins repressing apoptotic cell death by activating degradation of caspase-3, caspase-7, and caspase-9 through ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation (Muaddi et al., 2010). XIAP expression is mainly upregulated by an eIF2α phosphorylated mechanism at the translational level, contributing to cell survival. While ATF4 may contribute to caspase activation by promoting XIAP degradation, in turn, it impedes this process. Most importantly, different pharmacological compounds, such as CHOP, eIF-2α, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), are involved in UPR-induced apoptosis (details seen Box1). JNK (also known as stress-activated protein kinases, SAPKs) and caspases have also been involved in mediating apoptotic signals during ER stress (Ip and Davis, 1998). There currently is experimental evidence available to suggest the mechanisms. Upon ER stress, IRE1α determines the expression of JNK in wild-type fibroblasts and IRE1α−/− fibroblasts (Urano et al., 2000). Furthermore, under conditions of severe ER stress, mRNA IRE1 decay may promote cell death by degrading the mRNAs of anti-apoptotic proteins, thus tipping the balance towards apoptosis (Logue et al., 2013).

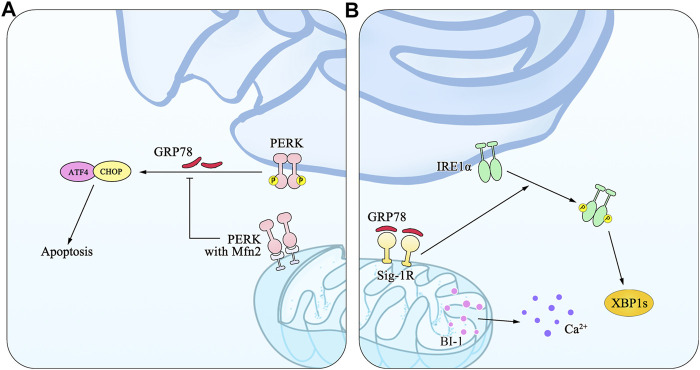

4.1.1 Box3 Mitochondria-Associated ER Membranes

The sites of physical communication between the ER and mitochondria are defined as mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) (OMM) (Wieckowski et al., 2009; Vance, 2015). Dynamin-like GTPase mitofusin-2 (Mfn2), one of the multiple proteins assembled by MAMs, is involved in regulating mitochondrial fusion through binding to PERK to inhibit PERK signaling and mediating mitochondrial functions (Santel and Fuller, 2001; Munoz et al., 2013). Furthermore, PERK is enriched at MAMs where it facilitates the tethering of the ER to mitochondria and sensitizes cells to apoptosis, which is also proved in the Mfn2−/− cells through several experimental models (Verfaillie et al., 2012; Munoz et al., 2013). The sigma 1 receptor (Sig-1R), local expression of chaperone proteins, is located at MAMs, and may bind to BiP to form a Sig-1R/BiP complex, through which it induces IRE dimerization and further activates the IRE1-XBP1 signaling pathway. MAMs are also known as multiprotein platforms, where Ca2+ releases are regulated by Bax-inhibitor-1 (BI-1). BI-1 is an antagonist of Bax that has a suppressive action on the IRE1-XBP1 signaling pathway. Consequently, the deficiency of BI-1 elicits IRE1 activation accompanied by its downstream enhancement (Lisbona et al., 2009). The detailed mechanism is illustrated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

An illustration of MAMs and mitochondrial dysfunction in ER stress. MAMs are the ER membranes at the MERCs, which form a stable bridge between the ER membrane and the OMM, whose fusion is mediated by Mfn1, Mfn2, and Sig-1R. (A) Mfn2 is involved in alterations of mitochondrial morphology through binding to PERK and inhibiting PERK signaling. (B) As the local expression of chaperone proteins, Sig-1/BiP activates the IRE1/XBP1 signaling pathway via IRE1 dimerization. BI-1 resides on the MAMs and regulates mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration and apoptosis.

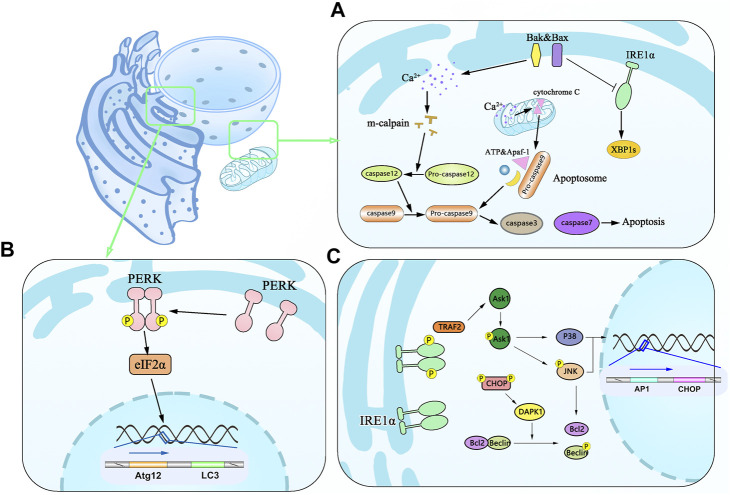

4.2 Mitochondrial Pathway of Apoptosis-Induced ER Stress

Two principal signaling pathways initiate apoptosis. One is the exogenous or death receptor pathway, while the other is the mitochondrial pathway. Notably, the latter frequently occurs when the cells are captured under the UPR condition. B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family proteins containing Bcl-2 associated X proteins (Bax) and Bcl-2 antagonists/killers (Bak), both localized to the mitochondrial outer membrane and the inner ER (Krajewski et al., 1993; Zong et al., 2003), are the major molecules of provoking the apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway. Cells deficient for both BAX and BAK become resistant with the stimulation of TG, TM, and brefeldin A (Wei et al., 2001). Activated Bax/Bak can lead to apoptosis via two different pathways. Firstly, Bax/Bak change conformation from inactive forms to active forms and oligomerize in the ER membrane upon ER stress, localizing the ER to regulate ER Ca2+ levels in the reticular lumen (Scorrano et al., 2003; Zong et al., 2003). A high concentration of cytoplasmic Ca2+ activates m-calpain, leading to the cleavage and activation of procaspase-12 (Nakagawa and Yuan, 2000) along with the downstream caspase-12 and activation procaspase-9. This, in turn, provokes several downstream effector caspases (caspase-3 and caspase-7) (Morishima et al., 2002; Vannuvel et al., 2013). Many feedback mechanisms, as summarized in the above paragraph, are essential for accurate assessments of caspase and ER stress, yet Ca2+ in the mitochondrial pathway should not be ignored. Mitochondria take up Ca2+ from the cytosol, leading to depolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane and the subsequent release of cytochrome c (Vannuvel et al., 2013), which can bind to Apaf-1, procaspase-9, and ATP to form apoptosome. This activates caspase-9, which causes the downstream executor to activate caspase-3, DNA fragmentation, to initiate cell death (Crompton, 1999; Shibue and Taniguchi, 2006). Apart from this, Bax and Bak have been found to interact directly with the cytosolic domain of IRE1 and decrease XBP1 expression (Hetz et al., 2006) (Lai et al., 2007). The main point can be summarized in Figure 3A: mitochondria are essential organelles responsible for cellular stress responsiveness.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic diagram of apoptosis associated with the mitochondrial pathway and autophagy induced by ER stress. (A) Effector proteins of Bax and Bak in apoptosis undergo conformational changes in active forms and oligomerize in the ER membrane leading to the efflux of Ca2+ from the ER to the cytoplasm and activating m-calpain to cleave and activate procaspase-12, which in turn activates caspase-3 and caspase-7. BAX and BAK are associated with the decreased expression of IRE1 and XBP1 and promote apoptosis. Ca2+ can be taken up by mitochondria leading to depolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane and cytochrome c release, which binds Apaf-1, procaspase-9, and ATP into apoptosome and activates caspase-9 and caspase-3, then resulting in cell death. (B) Dimmerized PERK phosphorylates the translation initiation factor eIF2α and mediates the translation of Atg12 and LC3. (C) Activated IRE1 forms P-IRE1α/TRAF2 complex and initiates Ask1 as a stress-responsive in the JNK and p38 pathways. Phosphorylated JNK along with activated P38 enters the nucleus to promote translation of AP1 and CHOP.

4.3 Correlation Between Autophagy and ER Stress

There is mounting evidence that autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process involving the regulation of cellular homeostasis via removing misfolded proteins and damaged organelles. Autophagy is the membrane trafficking pathway that delivers intracellular degraded material to lysosomes via the double-membrane vesicles, the autophagosomes (Inoue and Moriyasu, 2006; Liu and Bassham, 2012). Through the effect of ER stress, autophagy plays a protective role in a constitutive manner to enable the turnover of long-lived proteins, removal of damaged organelles, and misfolded proteins as a defense mechanism against pathogens (Yang et al., 2016). When the accumulation of damaged proteins in the ER has exceeded the repair capacity of ERAD, portions of the organelle can be specifically targeted for large-scale degradation through autophagy (Lajoie and Snapp, 2020). eIF2α phosphorylation induced by PERK works as a hotspot of stress-induced translation control (Kouroku et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010; Talloczy et al., 2002). This effect is associated with overexpression of the autophagy-related gene Atg2 and LC3 in vivo and in vitro. Numerous in vitro studies have demonstrated that PERK/ATF4/CHOP signaling mediates the upregulation of LC3 and Atg5 to drive specific phagophore formation phenomena (Mizushima, 2005; Rouschop et al., 2010) (Figure 3B). Notably, a recent report has shown the effect of CHOP contributing to apoptosis through upregulating the expression of the death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1). Furthermore, GRP78 overexpression is sufficient to induce UPR or autophagy through the IRE1 pathway after treatment with TM and dithiothreitol (Chan and Egan, 2005). Interestingly, some researchers believe that the cell autophagy signal transduction pathway induced by ER stress is IRE1 rather than PERK and ATF6. These challenges likely contribute to different conclusions in previous studies. We think these phenotype differences have been associated with different abundances in different tissues, partly due to differential ER stress models in different tissues.

The apoptosis mentioned above is regulated by the PERK/ATF4/CHOP protein family. However, the IRE1 modulatory role in autophagy and ER stress should not be ignored in the process. IRE1 binds TNF-receptor-associated factor-2 (TRAF-2) to form a complex that phosphorylates and activates the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1/MAP3K5 (ASK1), which in turn mediates the phosphorylation of ASK1 and induce c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK/MAPK8/SAPK1) phosphorylation, thus leading to Bcl-2 activation. This ultimately causes autophagy (Urano et al., 2000; Talloczy et al., 2002; Ogata et al., 2006; Kouroku et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010; Carreras-Sureda et al., 2017; Ishikawa et al., 2017). Prolonged activation of JNK-mediated stress is well known to instigate deleterious inflammation, leading to inflammation by triggering the secretion of proinflammatory chemokine (Kaser et al., 2008). Aside from TRAF2 binding to I-κ B kinase (IKK), activated NF-κB leads to the enhancement of pro-inflammatory TNF-α to facilitate stress-induced cell death (Hu et al., 2006; Li et al., 2011). To obtain support for the proposed mechanism and better understand the structural factors, including re-incarceration, a detailed illustration is shown in Figure 3C.

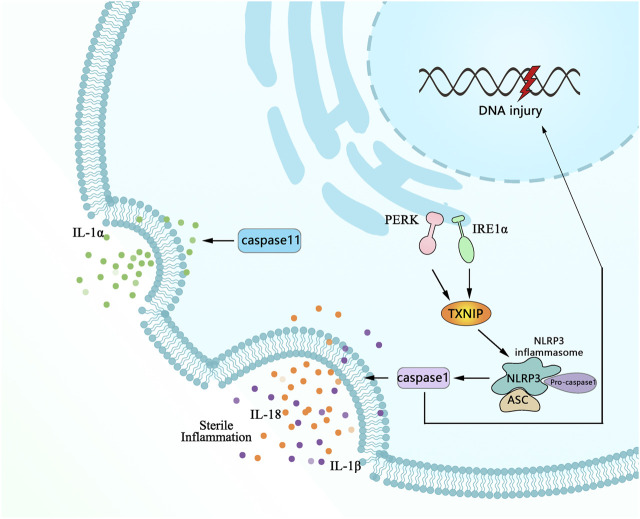

4.4 Correlation Between Pyroptosis and ER Stress

Pyroptosis, a prominent form of programmed lytic cell death mediated by pro-inflammation, is the best-characterized response (Brennan and Cookson, 2000). For this reason, understanding the molecular mechanisms regulating sustained ER stress-induced pyroptosis has been the subject of intense research efforts to identify either cause or alter risk (Zhou et al., 2020). Recent studies have revealed that exposure to hypoxia directly triggers pyroptosis under ER stress, as shown by the high immunoreactive nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family members, containing pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3), inflammatory caspase-1, and IL-1β. These mediators were identified as critical mediators of pyroptosis, and the detailing process is described in Figure 4. The activation of the inflammasome can cause a necrotic form of cell death termed pyroptosis (Dong et al., 2015; Jorgensen et al., 2016; Man et al., 2017). Currently, the view of the structure-function relationship of NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β has been widely accepted, a primary inflammatory mediator in initiation pyroptosis is the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1, the effector protease of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which is essential for pro-IL-1β and IL-18 secretion (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010; van de Veerdonk et al., 2011). There are several other approaches, such as thioredoxin, an oxidative stress mediator interacting protein (TXNIP) linked to NLRP3 inflammasome activation and serving as a marker for excessive ER stress and UPR activation (Cheng et al., 2019). More importantly, inhibiting ER stress with TXNIP siRNA and 4-phenyl butyric acid (PBA) prevents activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes (Luo et al., 2014) and so did IRE1αRNase specific inhibitor (STF-083010) (Ke et al., 2020).

FIGURE 4.

Schematic highlights of the complex network on multiple factors involved in signaling pathways for ER stress-induced pyroptosis. Following injury, pro-inflammatory mediators of proIL-1β, NLRP3, and caspase-11 are increased transcription. ProIL-1β and TXNIP facilitate the assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome that cleaves procaspase-1 to active caspase-1, which in turn leads to process maturation of the IL-1β and initiating pyroptosis with the feature of plasma membrane rupture and DNA fragmentation along with multifarious cytopathological changes.

5 Heat Shock Proteins and ER Stress

Heat shock proteins (HSPs), discovered in almost all organisms (Craig, 1985), are subdivided into distinct families according to their sequence homology and molecular weight: HSPH (former name HSP110), HSPC (HSP90), HSPA (HSP70), HSPD/E (HSP60/HSP10 and CCT (TRiC), DNAJ (HSP40) (the above so-called large HSPs), and HSPB (small HSP or sHSP, with the molecular weights of 12∼ 43 kDa) (Vos et al., 2008; Kampinga et al., 2009). Some of HSPs are expressed constitutively in normal cells. Likewise, the expressions of other HSPs are robustly enhanced in response during adverse conditions. Extensive studies have corroborated that HSPs, as organellar proteins (Krishna and Gloor, 2001; Emelyanov, 2002), guard the proteome against misfolding and aggregation of denatured proteins (Johnston et al., 1998).

The sHSPs share a homologous amino acid sequence called the “α-crystallin domain” (Caspers et al., 1995), which can form large oligomers due to environment-unfriendly conditions (Arrigo, 1990; Klemenz et al., 1991; Inaguma et al., 1993). Thereby, it is generally accepted that sHSPs are responsible for relieving ER stress alleviation via multiple regulatory pathways (Kim et al., 2008; Morimoto, 2008).

5.1 HSP27 (HSPB1)

In humans, HSP27 is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues, predominantly located in the cytosol and smaller portions in the membrane and cytoskeletal fractions. Full-length HSP27 comprises 205 residues but self-assemble into large, polydisperse oligomers depending strongly on external conditions (Jovcevski et al., 2015; Alderson et al., 2020). There is a general agreement on the correlations between HSP27 and ER stress. It was revealed that pretreatment of U373 MG human glioma cells with ER inducers, TM or TG, high expressions of HSP27, and αB-crystallin were induced, and the phosphorylation of HSP27 was upregulated by mediating activation of the p38 MAP kinase pathway (Ito et al., 2005). Notably, it is postulated that HSP27, as a cellular stress sensor, not only is a potent inhibitor of apoptosis responding to diverse stress (Rogalla et al., 1999; Samali et al., 2001) but also attenuates ER stress-induced intrinsic apoptosis through downregulated expression of annexin, procaspase-9/procaspase -3, and caspase-3/caspase-7, due to their vital role in ERK-mediated phosphorylation and the proteasomal degradation of BIM (Kennedy et al., 2017). Endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 (ERp29) involved in ER stress is closely related to HSP27. Some evidence confirmed that overexpression of ERp29 in cancer, including breast cancer (Mkrtchian et al., 2008), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Wu et al., 2012), and pancreatic cancer (Mori-Iwamoto et al., 2007), can raise the expression of Hsp27, thereby decreasing apoptosis. It is worth mentioning that HSP27 involves regulating multiple processes in cells and suggesting that HSP27 represents a new therapeutic target for some special diseases (details seen Table 1). However, further investigations are required to reveal the more detailed associations between HSP27 and ER stress.

TABLE 1.

Small and large HSPs involved in diseases.

| 1 | S | Name | Disease | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Small HSPs | HSP27 | Colorectal cancer; breast cancer; oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma | Wang et al. (2009), Yu et al. (2010), Thuringer et al. (2015), Wang et al. (2020) |

| 3 | α-Crystallins | Tumors; neurodegenerative diseases; ocular diseases | Renkawek et al. (1994), Dimberg et al. (2008), Kase et al. (2011) | |

| 4 | HSP70 | Lung cancer; acute myeloid; leukemia; colorectal cancer; gastric cancer | Kocsis et al. (2010), Lee et al. (2013), Piszcz et al. (2014) | |

| 5 | HSP90 | Lung adenocarcinoma; esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; breast cancer | Park et al. (2015), Xu et al. (2016), Moyano et al. (2021) | |

| 6 | Large HSPs | HSP110 | Brain ischemia, kainic acid-dependent cell injury, cerebellar Purkinje cell degeneration | Ni and Lee (2007), Sokka et al. (2007), Su and Li (2016) |

5.1.1 α-Crystallins

α-crystallins belonging to the sHSP superfamily possess two isoforms: αA-crystallin (HSPB4) and αB-crystallin (HSPB5). They are characterized by the presence of a conserved crystallin domain flanked by a variable N-terminal domain and C-terminal extension. In humans, αA-crystallin is distributed only in the eye lens, while αB-crystallin is found in different tissues (Sprague-Piercy et al., 2021). In the ocular lens, αB-crystallin is predominantly located on the rough ER with smooth membranes (Suetsugu et al., 2010). In the ER stress cell model, a high level of α-crystallins was detected (Ito et al., 2005). It is found that αA-crystallin can recognize misfolded subunits of epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) on the ER membrane and degrade ENaC subunits via the ERAD process (Kashlan et al., 2007). Intriguingly, αB-crystallin negatively regulated apoptosis induced by ER stress (Dou et al., 2012). A study illustrated that a mutant of αB-crystallin named αB-crystallin R120G induced ER stress and impaired Ca2+ regulation, resulting in aging-related cardiac dysfunction, arrhythmias, decreased autonomic tone, and shortened lifespan in the mice model (Jiao et al., 2014). In summary, these studies opened new exploratory research avenues with the possibility of identifying α-crystallins as a potential treatment target.

5.2 HSP70

HSP70 proteins possess a highly conserved 44 kDa N-terminal ATPase domain, 18 kDa substrate-binding domain, and 10 kDa C-terminal domain (Liu et al., 2012). The expression of HSP70 has been reported to be present in the extracellular milieu via independent of ER-Golgi-mediated protein trafficking to prevent aggregation and promote refolding of misfolded denatured proteins, as well as solubilizing aggregated proteins and cooperating with cellular degradation machinery. Among its functions, HSP70s act as sentinel chaperones, protecting cells against the deleterious effects (Craig, 2018). The member of HSP70s, GRP78 (also known as HSPA5), given that it has been extensively discussed in other parts of this review.

5.3 HSP90

HSP90 encoded by gene HSPC1∼5 (Kampinga et al., 2009) is composed of five members in the features of highly conserved molecular chaperones involved in modulating many cellular processes under both physiological and stress conditions. Glucose-regulated protein 94 (GRP-94) is an HSP90 analogue resident in ER (Lamoureux et al., 2014).

5.4 HSP110

HSP110, identified in the ER of all eukaryotic cells (Hatayama et al., 1997), is an essential component in almost all eukaryotic cells. HSPH4, also known as 150 kDa oxygen-regulated protein (ORP150), belonging to the HSP110 family, serves as a nucleotide exchange factor for GRP78 in the ER due to its ADP-ATP exchange function (Dragovic et al., 2006) and regulates immunoglobulin folding and assembly in concert with GRP78 (Easton et al., 2000), as well as directly participates ER stress as an independent chaperone (Behnke et al., 2015; Nowakowska et al., 2020). Expression of HSPH4 in the ER at very high levels was induced by brain ischemia (Su and Li, 2016), kainic acid-dependent cell injury (Sokka et al., 2007), and cerebellar Purkinje cell degeneration (Ni and Lee, 2007). However, to date, no drug targeting HSP110 was described.

6 Link of Intestinal Disease and ER Stress

Solid evidence has demonstrated that abnormal levels of ER stress are emerging as a driving factor for a wide variety of diseases, including ischemia/reperfusion injury, diabetes, neurodegeneration, and cancer. Environmental stresses, such as microbial infection from food-borne pathogens, are colonized by a diverse and complex community of commensal and pathogenic microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. These can cause intestinal inflammation and systemic stress responses and are also associated with ER stress and devastating major mental disorders. Notably, metabolic studies have shown that these microbes generate metabolites serving as energy sources for cell metabolism, promote the development and the functionality of the immune system, and prevent colonization by pathogenic microorganisms. Different cell types differ in their preferred mode of metabolism to harness the energy and generate its required set of metabolites. As solid cancers grow, ER stress is inevitably induced by hypoxic and nutrient insufficiency. Furthermore, observations illustrated that activation of the UPR in hypoxic tumors contributes to exacerbating autophagy. In conclusion, ER stress plays an important role in many diseases.

6.1 IBD and ER Stress

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a family of chronic inflammatory diseases of all or part of the digestive tract, characterized by a complex and dysregulated immune response. Incidence rates worldwide are increasing. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two primary forms of IBD, which has long received attention from scientists interested in a variety of recurrent and unprovoked symptoms appearance; however, most remain unknown.

Recently, an increasing amount of direct experimental evidence indicates that ER stress has been implicated as a major stress-response contributor in the process of occurrence and development of IBD (Rees et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). First of all, various physiological and pathological situations produce alterations in the ER in the animal model of DSS-induced colitis IBD (Yin et al., 2021). This theory was further confirmed in the cells and organoids from human specimens, even the tissue directly derived from IBD patients (Pierre et al., 2020; Rees et al., 2020). Enteroid-derived primary cell monolayers generated from IBD subjects exhibited significantly lower basal expression of GRP78 and higher basal CHOP expression and XBP1s/XBP1u ratios compared to the healthy control subjects. Specifically, ER stress-related genes obtained from the CD patients’ intestinal mucosa, including ATF3, DNAJC3, STC2, DDIT3, CALR, HSPA5, and HSP90B1, showed high expression in comparison with the normal group. Most commonly, changes in mucus associated with Grp78 expression have been increased in the ileal mucosa of CD patients. At the same time, XBP1s levels were also increased between inflamed and non-inflamed ileal/colonic CD or colonic UC mucosa. At the same time, the expression of ERN1 genes is upregulated to support the increased demands of XBP1s protein from autophagy activity. Although these studies are not identical in a significant change of mucosal inflammation in patients with CD and UC, these data indicated that IRE1 activity was increased in the CD ileum and colon (Kaser et al., 2008). The results were also supported by recent discoveries. In the ileum and the colon of patients with CD, immunochemistry confirmed the presence of ER stress in the mucosa of ileal and colonic ulcer edges (Pierre et al., 2020). It is worth mentioning that ER stress may contribute to the development of fibrosis in patients with CD (Li et al., 2020). The normal human intestinal fibroblast cell line CCD-18Co cells incubated supernatant of HT-29 cells pre-conditioned by TM occurred the fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation (Vieujean et al., 2021). Of note, these ER stress response proteins are also involved in restoring the integrity of the epithelial barrier through participating in proper protein folding, ERAD, or ER stress-mediated apoptosis.

Importantly, an increasing number of studies indicate considerable overlap of IBD pathophysiology and IRE1. Ern1 knockout (KO) in mice directly leads to death during the state of embryonic process (Iwawaki et al., 2009), while Ern2 KO in mice results in increased ER stress, shortened latency of colitis, exacerbated DSS-induced colitis, induced idiopathic colitis (Bertolotti et al., 2001; Kurashima and Kiyono, 2017), and aggravated severity of colitis. Different results were drawn in the case of genetic ablation of Ire1α in IECs. Conditional deletion of IRE1α in IECs results in loss of goblet cells through induction of CHOP and failure of intestinal epithelial barrier function. This contributes to sensitize cells to LPS, an endotoxin from bacteria, eventually leading to spontaneous colitis and higher susceptibility to chemical-induced colitis in mice (Zhang et al., 2015). These results suggest that to maintain intestinal epithelial homeostasis, the IRE1α functions play an important role in defending against IBD. Reports have revealed that the human IRE1β gene maps to the pericentromeric region of chromosome 16 within a single PAC interval of the polymorphic simple sequence repeat D16s417 harboring one or more genes implicated in modifying the risk for the development of IBD (Hugot et al., 1996; Brant et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1998). The role of IRE1β can be uncovered by the deletion of genes. IRE1β–/– mice exhibited highly elevated BiP in the colonic mucosa. Through a longitudinal follow-up of up to 1 year, IRE1β–/– mice did not spontaneously develop intestinal inflammation, when exposed to DSS, and IRE1β–/– mice pronounced earlier alterations compared to wild-type mice, including marked shortening of the long axis, inflammatory cells infiltration consisting predominantly of mononuclear cells, and ulceration consisting of focal lesions interspersed with areas with intact surface epithelium, which suggested that mutant mice were prone to developed colitis earlier. Apart from this, expression of ICAM-1, an inflammation marker, was earlier detected in mutant mice than that in wild type (Bertolotti et al., 2001).

In order to elucidate the role of the Xbp1 in the intestine, Kaser et al. (2008) generated the model of Xbp1flox/flox Villin-Cre (Xbp1−/−) transgenic mice. Through this, Kaser et al. demonstrated that the model mice were characterized by boosting responses of IEC to mucosal inflammatory signals including JNK, CXCL1, and TNFα, exhibiting abscess and ulceration in the intestinal crypt and multinucleated infiltration in the lamina propria. These data suggested that Xbp1−/− mice had more severe intestinal inflammation and higher susceptibility to spontaneous enteritis than wild-type mice (Adolph et al., 2013).

More recently, studies have linked ATF6 to IBD. Expression of activated ATF6, TNF, and other inflammatory cytokines increased in ileal IECs from CD patients and in organoids from Xbp1ΔIEC mice (Stengel et al., 2020).

Mucins build the first defense line, protecting the gastrointestinal tract from antimicrobial factors to maintain homeostasis. Goblet cells serve as mucin-producing cells found scattered among other cells of the intestinal villi and crypts in lesser numbers than the absorptive cells. ER stress increased MUC5AC protein production and secretion in human airway epithelial cells via the IRE1α and XBP1 signaling pathways (Xu et al., 2021). More interestingly, studies indicated that cells devoted to secreting encompassing goblet and Paneth cells in the gut are the major targets of intestinal ER stress (Zhao et al., 2010; Kaser et al., 2011; Larabi et al., 2020). In Xbp1−/− mice, Paneth cells were almost undetectable in the intestine tract by electron microscopy and analyzing mRNA. Alterations also took place in the number and size of goblet cells in the intestine, not in the colon upon Xbp1 deletion, despite the slight decrease in numbers and size (Kaser et al., 2008). The Winnie and Eeyore mouse model with MUC2 missense mutations showed elevated ER stress of goblet cells, which decreased the number of goblet cells, impaired mucus barrier, and developed colitis spontaneously.

Notably, goblet cell and secreted mucus phenotypes represent important differences between the two diseases: Crohn’s disease is characterized by an increase in goblet cells and a thicker mucus layer (Dvorak et al., 1980; Trabucchi et al., 1986). In contrast, there is a reduction in goblet cells, decrease in MUC2 production (Tytgat et al., 1996; Van Klinken et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2019), accumulation of MUC2 precursor (Hanski et al., 1999), and reduction in secreted mucus in UC (Heazlewood et al., 2008; Samoila et al., 2020). These studies highlight the sensitivity of goblet cells to ER stress and the importance of proper MUC2 processing in maintaining goblet cell health and overall mucosal homeostasis.

More recently, it was suggested that the degree of drug-induced ERS aggravation correlates with MUC2 expression levels and that high mucin-producing cells are more susceptible to drug-mediated ERS aggravation (Dilly et al., 2020).

Collectively, ER stress exerts its multifaceted role on IBD.

6.2 Colon Cancer

Many studies have established the complex and important roles of ER stress in contributing to the development and progression of colorectal cancer (Ryan et al., 2016). In this review, we summarized the suggestions and proposed new therapeutic strategies based on the results of the present and previous studies. In explant tissue from mucinous colon cancers, significantly high expression levels of MUC2, GRP78, ATF4, and CHOP protein were detected (Dilly et al., 2020).

Notably, PERK has an explicit connection with the tumor cells’ survival. PERK phosphorylation of eIF2α was required to grow solid tumors (Bi et al., 2005). Cells sharing the ability to resist ER stress and multiple chemotherapeutic agents revealed higher PERK expression through a genetic profile analysis. In turn, inducible silencing PERK reduced tumor growth and restored chemotherapeutic sensitivity in resistant tumor xenografts (Salaroglio et al., 2017). Angiogenesis is generated to escape the predicament of hypoxic conditions in cancer formation. Strikingly, the PERK-ATF4 pathway can directly promote vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and suppress angiogenesis inhibitors such as angiostatin, PF4, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) (Blais et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2012).

IRE1α is also a vital participant in tumor development. As research reported, deletion of IRE1α decreased VEGF, which is crucial for angiogenesis and inhibits tumor growth (Drogat et al., 2007). Another report proposed that the knockdown of IRE1α suppressed the proliferation of colon cancer cells in vitro and xenograft growth in vivo through repressing the expression of β-catenin, a key factor that drives colonic tumorigenesis, thereby activating eIF2α signaling. The IRE1a-specific inhibitor 4μ8C could suppress the production of β-catenin, inhibit the proliferation of colon cancer cells, repress colon CSCs, and prevent xenograft growth. The results suggest that IRE1α has a critical role in colonic tumorigenesis, and IRE1α targeting might be a strategy for treating colon cancers (Li et al., 2017). Another study showed that, in the case of gene deletion of IRE1α, colon cancer cells are sensitive to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor KRAS mutants (Sustic et al., 2018). However, the deletion of IRE1α resulted in tumor invasion (Auf et al., 2010).

Compared to the control group, the expression levels of IRE1β and MUC2 proteins were decreased in the tumor and resisted inflammation, thus promoting the occurrence and development of colonic tumors (Dai et al., 2019). IRE1β appears to specifically play its RNase role in highly differentiated secretory cells such as goblet cells, thereby degrading the mRNA encoding specific secretory proteins, including MUC2 (Nakamura et al., 2011; Tsuru et al., 2013). Colorectal cancer (CRC) tissue samples were surgically resected tumor tissues from patients from 44 to 82 years with colorectal adenocarcinoma. IRE1β and MUC2, the mRNA expression and protein levels, were significantly decreased compared to the noncancerous tissues. Strikingly, it was identified that the IRE1β mRNA expression levels were positively associated with the MUC2 mRNA expression levels. IRE1β, regardless of the transcriptional and translational level, was significantly higher in those patients with lymphatic metastasis or stages III-IV of CRC (Jiang et al., 2017).

Meanwhile, the role of the IRE1-XBP1 pathway in the tumor has been comprehensively explored (Bi et al., 2005; Feldman et al., 2005). XBP1s can partly protect the tumor from hypoxia, while deficiency of Xbp1 can hinder hypoxic tumor growth (Romero-Ramirez et al., 2004; Feldman et al., 2005). Simultaneously, apoptosis was increased in the Xbp1-deficient cells, thereby inhibiting tumor growth. Taken together, these studies directly suggested that XBP1 is an essential survival factor for hypoxic stress and tumor growth. Four colon cancer cell lines (DLD1, SW480, HCT15, and WiDr) showed increased expression of XBP1. The tendency of high expression of XBP1 in the level of mRNA and protein also occurred in the patients who suffered from colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma (Fujimoto et al., 2007).

ER stress destroys the effectiveness of traditional treatments, including chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapies in the course of cancer treatment (Avril et al., 2017), decreases the risk for recurrence, and accelerates death (Andruska et al., 2015). In other words, ER stress contributes to tumor survival, especially in colorectal cancer (CRC) (Ryan et al., 2016). ER stress can alleviate cancer cells death and promote survival and metastasis. One study utilized the colon tissue of Winnie that is a mouse model of chronic ER stress and wild-type BLK6 mice to validate the expression of survivin, one of the IAP inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) that binds to caspase activation involved in apoptosis to protect cells from apoptosis. The results showed that the level of survivin in Winnie is higher than that in the wild type. Results indicated that, with the presence of ER stress, the level of ER stress markers and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 is remarkably higher. In contrast, the level of inflammatory markers is significantly lower compared to those with the absence of ER stress, which directly served as a convincing argument demonstrating the beneficial role of ER stress in the survival of cancer cells. As Nrf2 involved in chemoresistance is promoted by PERK in HT29 colon cancer cells (Salaroglio et al., 2017), researchers attached the importance of PERK and CHOP to GADD34 dephosphorylating eIF2α, providing an insight that suppression of the CHOP-GADD34 axis may be a tumor survival mechanism (Clarke et al., 2014). Notably, the induction of GADD34 may have a broad effect on tumor-suppressive effects. In contrast, the sensibility of human colon cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) chemotherapy would recover after genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of the PERK-ATF4 pathway (Shi et al., 2019).

However, when ER stress is severe and induces cell death, divert results will work out. Many studies in the cell level targeted for colon cancer treatment pointed out that cell death induced by ER stress may target antitumor medicine (Tung et al., 2015; Dilly et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021).

Tremendous studies have corroborated the vital roles of GRP78 in the occurrence of colon cancer, resulting from GRP78 working as the main chaperone participating in protein folding. Firstly, the authors artificially separated GRP78 positive and negative sub-populations from HM7 and GRP78 HCT116 cell lines using anti-GRP78 antibody-coated magnetic beads and elucidated that receptor-positive and receptor-negative tumor cells manifest different properties in colorectal cancer. GRP78 negative cells were characterized by highly proliferative and significant growth in tumor size and bigger metastases than GRP78 positive cells. What is more, after silencing GRP78 expression using siRNA oligomers in the positive sub-population, proliferation induced a 53% increase. On the contrary, cells pre-incubated with doxorubicin, which induced GRP78 high expression, exhibited reduced proliferation and tumor growth (Hardy et al., 2012).

Studies have reported that autophagy induced by chemicals including A23187, TM, TN, and brefeldin A only conferred protection in specific colon cancer cells such as HCT116 cell lines rather than all the colon cancer cells (Ding et al., 2007). Parallel to the protective role of autophagy for a colon cancer cell, studies have corroborated the autophagic inhibition effect on anti-colon cancer via apoptosis induced by p53 activation and ER stress in vivo and in vitro. Inhibiting autophagy, specifically in the epithelial cell, was achieved in Atg5 flox/flox/K19CreERT+. Treating the mutant and controlling mice (Atg5 flox/flox) with azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate (AOM/DSS) induced colon cancer. A significant difference existed in the aspect of maximum and total sizes of the tumor due to smaller size in Atg5-deficient mice. Meanwhile, increased expression levels of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3, and GRP78 were detected in mutant mice, indicating that apoptosis was elicited and autophagic inhibition had an antitumor effect (Sakitani et al., 2015).

Colon cancer stem cells were characterized by high Wnt pathway activity and chlorogenic potential. They were more resistant to chemotherapy, whereas the features disappeared when the cells became more differentiated. Intriguingly, ER stress was reported to have differentiating effects conserved between normal intestinal stem cells and colon cancer stem cells. Subtilase cytotoxin AB, a bacterium-derived protease that explicitly cleaves ER chaperone GRP78, was administrated to the colon cancer stem cells to activate ER stress in vitro. When colon cancer stem cells with a high Wnt pathway sorted by FACS were exposed to subtilize cytotoxin AB or TG, stem cell markers such as OLFM4 and LGR5 were lost. On the contrary, differentiated cell makers increased. The expression of the inhibitor of intestinal stem cell-cycle progression P21Cip1/Waf1 or cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (CDKN1) was upregulated, and enterocyte markers CK20, VIL2, SI, and FABP2 increased. Of note, MUC2, a hallmark of secretory goblet cells, was downregulated, arguing that ER stress was subscribed to induce intestinal epithelial stem cells differentiation toward an absorptive phenotype rather than a secretory phenotype. It is worth noting that transient UPR activation may promote regenerating these cells, given that the expression of LGR5 was increased after exposure to subtilase cytotoxin AB for 48 h. Colon cancer stem cells are suggested to be more resistant to conventional chemotherapy compared to differentiated cancer cells (Colak et al., 2014). UPR activation sensitized cells toward oxaliplatin and 5-FU resulting from high expression of caspase-3. To a great extent, the in vivo manifestations were observed. Transient UPR activation elicited by treating mice with salubrinal, an inhibitor of phosphatizing of eIF2α, resulted in increased growth of xenografts derived from colon cancer stem cells. The above results indicated that UPR activation provides a window of opportunity to improve chemotherapy outcomes (Wielenga et al., 2015).

To date, many reports have linked ER stress to 5-FU resistance. 5-FU-resistant SNUC5 colon cancer cells (SNUC5/FUR cells) and drug-sensitive SNUC5 cells were used to explore the consequence of arising resistant reaction. SNUC5/FUR cells exhibited higher expression of GRP78, XBP1s, ATF6, phosphorylated PERK, and eIF2ɑ and recovered sensitivity to 5-FU when transfected with siRNA against GRP78, ATF6, and ERK (Kim et al., 2016). However, a recent study provided evidence that apoptosis of SNUC5/FUR cells can be induced by ER stress (Piao et al., 2021).

7 Treatment of Intestinal Diseases Targeting ER Stress

The therapeutic applications and intriguing pharmacological properties of ER stress have attracted great attention from medical researchers. Plenty of new studies corroborated that tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) has an important role in protecting against ER stress, and treatment with TUDCA ameliorates various models of colitis in mice (Cao et al., 2013; Hino et al., 2014; Laukens et al., 2014). Colon-targeted prodrugs of 4-PBA were designed and synthesized, and their colon-targeting property was evaluated. Furthermore, the drug’s effectiveness was shown by regulating ER stress in a model of colitis in rats (Kim et al., 2020).

In addition, many ER stress inhibitors are generated, such as benzodiazepines, baicalein, and 1-deoxymannojirimycin hydrochloride (Farooqi et al., 2015). More recently, surprisingly, a study disclosed that Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus acidophilus suppressed ER-mediated goblet cell stress and reduced colonic inflammation (Kim et al., 2019; Engevik et al., 2021).

In particular, small molecule modulators of the ER stress target normal binding sites by activating sites of three sensors machinery and altering the function of IRE1α’s RNase (Papandreou et al., 2011; Volkmann et al., 2011; Cross et al., 2012; Mimura et al., 2012). Several studies have found evidence, direct or indirect, to support the importance of IRE1α’s kinase in multiple pathway-involved in the regulation of the cell differentiation and proliferation of the host antitumor response in colon cancer. First, salicylaldehyde analogs were the first reported systematically in the field, such as specific IRE1 RNase inhibitors and 3-methoxy-6-bromosalicylaldehyde that selectively represses XBP-1, and mRNAs is, in turn, a selective degradation by IRE1 (Volkmann et al., 2011). In addition, salicylaldehyde-based inhibitors have many strengths, including SFT-083010, MKC-3946, and 4u8c, which contain ideal reactive electrophile for binding the sites of IRE1’s RNase via a covalent bond to form a functional pharmacophore, similar to the geometry of the reduced form of the Schiff base of salicylaldehyde in the K907 can active site of the RNase (Cross et al., 2012; Sanches et al., 2014), and the kinase and RNase activity of IRE1α are regulated by kinase inhibitors through two different modes. One is to occupy the kinase ATP-binding site of IRE1α that activates Xbp1 mRNA splicing, contributing to adaptive UPR and ER homeostasis. The other is to inhibit RNase through the same ATP binding sites. Consequently, ATP-competitive inhibitors bind and stabilize can cause allosteric switching of IRE1α′s RNase either on or off.

Apart from the above, highly potent and selective inhibitors of PERK’s kinase domain become hotspots for selective ER stress. Accordingly, the inhibition of PERK, GSK2606414, and GSK2656157 has emerged as a promising cancer therapy (Atkins et al., 2013), including the ATP-competitive inhibitor. However, we recognize that these studies are not exhaustive; these examples of small-molecule inhibitors against IRE1a and PERK highlight the therapeutic potential and risks of targeting the UPR in cancer. A more thorough discussion of therapeutics against the UPR should be referred to (Maly and Papa, 2014; Hetz et al., 2019). Due to the remarkably increased tendency of chaperone induced by ER-stress response, many studies have targeted chaperone as a therapeutic target. GRP94, as a common chaperone, HSP90 inhibitor geldanamycin and AUY922 causes cell death (Marcu et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2018). Strikingly, some of the agents are nonspecific inhibitors with lower toxicity displaying power and selectivity for GRP94 (Duerfeldt et al., 2012). See the summaries in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

List of drugs inhibiting ER stress.

| 1 | Drug name | Mechanism of inhibition | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4-Phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) | Suppressing oxidative stress by attenuating ER stress | Kim et al. (2020), Choi et al. (2021) |

| 3 | Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) | Stabilizing unfolded proteins to prevent their aggregation from the induction of autophagy | Ozcan et al. (2006) |

| 4 | Benzodiazepines | Selectively suppressing cell death associated with the IRE1 pathway though modulating phosphorylation of ASK1 and inhibiting downstream activation of JNK and p38 MAPK. | Kim et al. (2009), Zou et al. (2015) |

| 5 | Baicalein | Attenuating pyroptosis, alleviating ER stress-mediated apoptosis to activate the autophagy process | Wu et al. (2020) |

| 6 | 1-Deoxymannojirimycin | Inhibiting N-glycan processing in the ER to attenuate ER stress-induced cell death | Lu et al. (2006), Miyake and Nagai (2009) |

| 7 | Toyocamycin | IRE1 RNase inhibitors | Chien et al. (2014) |

| 8 | 3-Ethoxy-5,6-dibromosa-licylaldehyde | A salicylaldehyde analog, IRE1 RNase inhibitors | Volkmann et al. (2011), Chien et al. (2014) |

| A non-competitive inhibitor with respect to the XBP-1 RNA substrate | |||

| 9 | SFT-083010 | Aldehyde-based covalent as the inhibitors of the IRE1α′s RNase | Papandreou et al. (2011), Mimura et al. (2012) |

| 10 | MKC-3946 | Inhibiting IRE1α′s RNase | Mimura et al. (2012), Zhang et al. (2014), Sun et al. (2016) |

| 11 | 4u8c | Inhibiting IRE1α′s RNase | Nelson et al. (2018), Wang et al. (2019a), Cao et al. (2019) |

| 12 | GSK2606414 | Inhibiting PERK’s kinase | Axten et al. (2013) |

| 13 | GSK2656157 | An ATP-competitive inhibitor of PERK enzyme | Axten et al. (2013) |

| 14 | Geldanamycin | Inhibiting GRP 94 | Marcu et al. (2002) |

| Nonspecific HSP 90 inhibitor | |||

| 15 | 17-AAG (Phases I–III), SNX-5422 (Phase I), CNF 2024 (Phase II), and NVP-AUY922 (Phases I/II) | Specific HSP 90 inhibitor | Duerfeldt et al. (2012) |

| 16 | Overexpression of BiP1 or BiP3 | Impede the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER | Otero et al. (2010) |

8 Conclusion

ER stress has been hotly debated due to its vital role in disease initiation and progression. What role does ER stress act in the process of disease? Is it beneficial, harmful, or both? Much research was attempted to unravel the mysterious veil of ER stress. ER stress, as a reaction to the unbalanced environment, is protective for cells. However, things can turn upside down when stress is chronic or otherwise irremediable. Therefore, future research should tackle this challenging question to understand the intricate interaction between ER stress and diseases. How ER stress can continue to play its positive role is another issue. Many studies focused on the treatment targeting ER stress by inhibiting or activating some ER stress members, which is a potent way to alleviate diseases. So far, there has been limited research that explores the relationship between stress and disease. Therefore, more effort in this area would further our understanding and treatment of diseases.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Yixuan Du, department of Oral Medicine of Capital Medical University, Beijing, China, for her contributions on the first draft of the figures. Authors thank Lucia Zhang who is a student of Loomis Chaffee School, Windsor, CT, United States. She corrected the grammer mistakes and polished the manuscript. Her contributions made our review with high quality and more reasonable.

Author Contributions

HG wrote the manuscript. CH, RH, BW, and LG polished the images. YG, CL, and HS contributed to writing. HG, ZL, and J-DX revised the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 82174056, 81673671 J-DX).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

DDIT3, DNA damage-inducible transcript 3; DTT, dithiothreitol; eIF2α, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α; ERO1α, endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1; GADD34, growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible 34; GRP94, glucose-regulated protein 94; HSP, heat shock protein; IKK, IκB kinase; MAMs, mitochondria-associated membranes; MAPKs, mitogen-activated protein kinases; Mfn2, mitofusin-2; NLRP3, nod-like receptor protein-3; PP1C, protein phosphatase 1C; RIDD, regulated IRE1-dependent mRNA decay; ROS, reactive oxygen species; S1P, site-1 protease; S2P, site-2 protease; TM, tunicamycin; TRAIL-R1/DR4, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor 1; TRAIL-R2/DR5, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor 2; TUDCA, tauroursodeoxycholic acid; TXNIP, thioredoxin interacting protein; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; XBP1, X-binding protein 1; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein.

References

- Adolph T. E., Tomczak M. F., Niederreiter L., Ko H.-J., Böck J., Martinez-Naves E., et al. (2013). Paneth Cells as a Site of Origin for Intestinal Inflammation. Nature 503, 272–276. 10.1038/nature12599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson T. R., Ying J., Bax A., Benesch J. L. P., Baldwin A. J. (2020). Conditional Disorder in Small Heat-Shock Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 3033–3049. 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andruska N. D., Zheng X., Yang X., Mao C., Cherian M. M., Mahapatra L., et al. (2015). Estrogen Receptor α Inhibitor Activates the Unfolded Protein Response, Blocks Protein Synthesis, and Induces Tumor Regression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4737–4742. 10.1073/pnas.1403685112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo A. P. (1990). Tumor Necrosis Factor Induces the Rapid Phosphorylation of the Mammalian Heat Shock Protein Hsp28. Mol. Cel Biol 10, 1276–1280. 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1276-1280.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins C., Liu Q., Minthorn E., Zhang S.-Y., Figueroa D. J., Moss K., et al. (2013). Characterization of a Novel PERK Kinase Inhibitor with Antitumor and Antiangiogenic Activity. Cancer Res. 73, 1993–2002. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-3109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auf G., Jabouille A., Guerit S., Pineau R., Delugin M., Bouchecareilh M., et al. (2010). Inositol-requiring Enzyme 1 Is a Key Regulator of Angiogenesis and Invasion in Malignant Glioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 15553–15558. 10.1073/pnas.0914072107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril T., Vauléon E., Chevet E. (2017). Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling and Chemotherapy Resistance in Solid Cancers. Oncogenesis 6, e373. 10.1038/oncsis.2017.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axten J. M., Romeril S. P., Shu A., Ralph J., Medina J. R., Feng Y., et al. (2013). Discovery of GSK2656157: An Optimized PERK Inhibitor Selected for Preclinical Development. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 4, 964–968. 10.1021/ml400228e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- B'Chir W., Maurin A. C., Carraro V., Averous J., Jousse C., Muranishi Y., et al. (2013). The eIF2α/ATF4 Pathway Is Essential for Stress-Induced Autophagy Gene Expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 7683–7699. 10.1093/nar/gkt563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke J., Feige M. J., Hendershot L. M. (2015). BiP and its Nucleotide Exchange Factors Grp170 and Sil1: Mechanisms of Action and Biological Functions. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 1589–1608. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti A., Wang X., Novoa I., Jungreis R., Schlessinger K., Cho J. H., et al. (2001). Increased Sensitivity to Dextran Sodium Sulfate Colitis in IRE1β-Deficient Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 585–593. 10.1172/jci11476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti A., Zhang Y., Hendershot L. M., Harding H. P., Ron D. (2000). Dynamic Interaction of BiP and ER Stress Transducers in the Unfolded-Protein Response. Nat. Cel Biol 2, 326–332. 10.1038/35014014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettigole S. E., Glimcher L. H. (2015). Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 33, 107–138. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi M., Naczki C., Koritzinsky M., Fels D., Blais J., Hu N., et al. (2005). ER Stress-Regulated Translation Increases Tolerance to Extreme Hypoxia and Promotes Tumor Growth. Embo J. 24, 3470–3481. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais J. D., Addison C. L., Edge R., Falls T., Zhao H., Wary K., et al. (2006). Perk-dependent Translational Regulation Promotes Tumor Cell Adaptation and Angiogenesis in Response to Hypoxic Stress. Mol. Cel Biol 26, 9517–9532. 10.1128/mcb.01145-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brant S., Fu Y., Fields C., Baltazar R., Ravenhill G., Pickles M., et al. (1998). American Families with Crohn's Disease Have strong Evidence for Linkage to Chromosome 16 but Not Chromosome 12. Gastroenterology 115, 1056–1061. 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan M. A., Cookson B. T. (2000). Salmonella Induces Macrophage Death by Caspase-1-dependent Necrosis. Mol. Microbiol. 38, 31–40. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]