Abstract

Introduction

Approximately 33–50% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) develop organ damage within 5 years of diagnosis. Real-world studies that capture the healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs associated with SLE-related organ damage are limited. The aim of this study was to evaluate HCRU and costs associated with organ damage in patients with SLE in the USA.

Methods

This retrospective study (GSK study 208380) used the PharMetrics Plus administrative claims database from 1 January 2008 to 30 June 2019. Patients with SLE and organ damage were identified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/10 codes derived from the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index. The first observed diagnosis of organ damage was designated as the index date. Selection criteria included: ≥18 years of age; ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient claims for SLE (≥30 days apart before the index date; ICD-9: 710.0 or ICD-10: M32, excluding M32.0); ≥1 inpatient or ≥3 outpatient claims for organ damage within 6 months for the same organ system code; continuous enrollment of 12 months both pre- and post-index date. The proportion of patients with new organ damage, disease severity, SLE flares, SLE-related medication patterns, HCRU and all-cause costs (2018 US$) were assessed 12 months pre- and post-index date.

Results

Of the 360,803 patients with a diagnosis of SLE, 8952 patients met the inclusion criteria for the presence of new organ damage. Mean (standard deviation (SD)) age was 46.4 (12.2) years and 92% of patients were female. The most common sites of organ damage were neuropsychiatric (22.0%), ocular (12.9%), and cardiovascular (11.4%). Disease severity and proportion of moderate/severe flare episodes significantly increased from pre- to post-index date (p < 0.0001). Overall, SLE-related medication patterns were similar pre- versus post-index date. Inpatient, emergency department and outpatient claims increased from pre- to post-index date and mean (SD) all-cause costs were 71% higher post- versus pre-index date ($26,998 [57,982] vs $15,746 [29,637], respectively).

Conclusions:

The economic impact associated with organ damage in patients with SLE is profound and reducing or preventing organ damage will be pivotal in alleviating the burden for patients and healthcare providers.

Keywords: systemic lupus erythematosus, organ damage, healthcare resource utilization, cost

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic relapsing and remitting autoimmune disease that affects multiple organs and can periodically worsen via flare episodes or manifest as a persistently active disease.1,2 The incidence and prevalence of SLE is nearly nine times higher in females than males3,4 and more common in people of African, Hispanic and Asian ancestry, with the highest occurrence of SLE reported in North America.5,6 Diagnosis of SLE typically occurs at a mean age of 35 years, 5 with approximately 33–50% of patients with SLE developing irreversible organ damage within 5 years of diagnosis7–9 due to a combination of longer patient survival, continued disease activity and SLE treatment toxicity induced by prolonged medication exposure.10,11 Approximately 80% of organ damage that occurs after diagnosis of SLE is directly or indirectly attributable to prednisone use, 12 with the risk of developing new organ damage increasing proportionally with increasing prednisone exposure. 13 Although low disease activity or remission have been associated with less accumulated damage, 14 even with low disease activity, patients can still develop organ damage due to the involvement of other risk factors. 9

Accumulation of organ damage can affect multiple organs, including skin, kidneys, eyes, and the musculoskeletal, neurologic, and cardiovascular systems,11,15 all of which are associated with poor health-related quality of life,16,17 further damage accrual, and increased mortality rates.15,18–21

There is no single biomarker to assess organ damage in SLE. While there are a number of disease activity measures available to physicians (e.g. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Index (BILAG)), they reflect measures of current disease activity but do not capture disease features attributable to organ damage.22,23 The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology (SLICC/ACR) Damage Index (SDI)24–26 is a measure of chronic, permanent organ damage. The SDI is a validated instrument, scoring irreversible damage that has been present for at least 6 months and occurred after the diagnosis of SLE. 27 Application of the SDI identified age, gender, race/ethnicity, disease activity and duration, and chronic steroid and immunosuppressant exposure as risk factors that significantly influence organ damage development, with the probability of death increasing with higher SDI scores.27,28

Organ damage is associated with a substantial economic burden, with previous studies showing significantly greater healthcare cost accrued for patients with organ damage than for those without.10,18,29–31 Despite the strong correlation between organ damage and increased healthcare costs, morbidity and mortality,18,27,28,32 recent real-world studies on the impact of organ damage in SLE on healthcare costs and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) are limited. While the SDI and other clinician-reported outcome measures (e.g. the SLEDAI) have been used in controlled clinical settings, the real-world use of these measures has been limited, which has hindered the quantification of the economic impact of organ damage. Considering the positive impact of emerging new treatments for SLE in delaying and/or preventing the accrual of organ damage, 33 there is a need to characterize the economic implications associated with organ damage in patients with SLE. In this regard, the aim of this study was to assess the burden of organ damage, in terms of healthcare costs and HCRU, in adult patients with SLE from the perspective of third-party payers in the USA.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was an observational retrospective study (GSK study 208380) conducted using administrative claims (medical and pharmacy) and enrollment data from the PharMetrics Plus database. This database covers enrollees from diverse geographic regions who are similar to the national, commercially insured population. It includes information on patient demographics and periods of health plan enrollment; primary and secondary diagnoses; detailed information about hospitalizations, diagnostic testing and therapeutic procedures; inpatient and outpatient physician services; prescription drug use; and cost data in the form of managed-care reimbursement rates for each service. This study used fully de-identified data and as such was not classified as research involving human participants. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

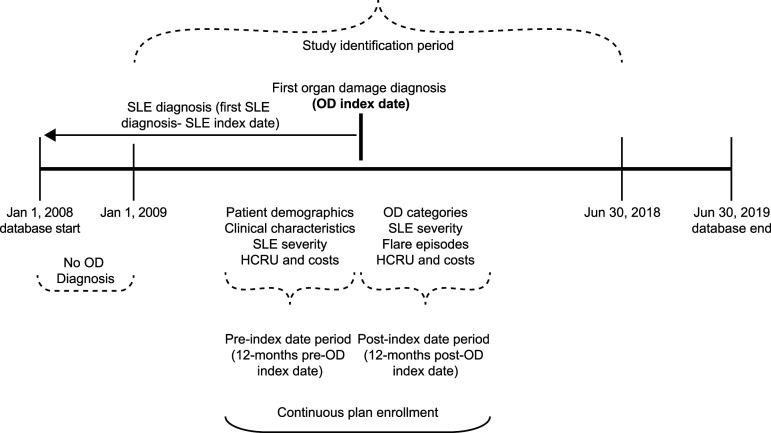

Figure 1 illustrates the study design, in which patients with SLE were identified between 1 January 2009 and 30 June 2018 (identification period). As organ damage measured by the SDI is not captured in administrative claims data, an algorithm based on diagnosis and place of service codes (e.g. outpatient vs inpatient) was employed as a proxy for organ damage. The algorithm categorized patients into one of 12 organ domain subgroups based on the first identified affected organ system on the SDI (cardiovascular, diabetes, gastrointestinal, malignancy, musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, ocular, peripheral vascular, premature gonadal failure, pulmonary, renal, and skin)24,34; and may have indexed to multiple organ system domains if patients had diagnoses for multiple organ systems on the index date. The index date was defined as the date of the first observed claim with an organ damage diagnosis. The 12 months before and after the index date were defined as the pre- and post-index date periods, respectively. Healthcare costs and HCRU were calculated and compared in the 12-months pre- and post-index date periods.

Figure 1.

Study design. HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; OD, organ damage; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Study population

Patients were required to meet the following study inclusion criteria: ≥1 inpatient claim or ≥3 outpatient claims within a 6-month period with an International Classification of Diseases, ninth and 9th 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM) diagnosis code for a medical condition for one of the 12 organ system domains listed in the SDI24,34 within the same organ system domain between 1 January 2009 and 30 June 2018; at least 12 months of continuous medical and pharmacy coverage before the index date; at least 12 months of continuous medical and pharmacy coverage after the index date; ≥1 inpatient visit or ≥2 outpatient visits (≥30 days apart) with an ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis code of SLE in the pre-index date period (ICD-9-CM code: 710.0; ICD-10-CM code: M32). In addition, patients had to be ≥18 years of age at SLE diagnosis. Patients with confirmed drug-induced SLE (ICD-10-CM code: M32.0) were excluded from the study.

Variables and outcome measures

Study variables and outcome measures included patient baseline characteristics, SLE disease severity and flares, HCRU, and healthcare costs. Baseline characteristics assessed at the index date included age, sex, health plan type, geographic region, index year, and metropolitan statistical area. Clinical variables assessed included SLE-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) 35 and comorbid conditions. Comorbidities were identified by the presence of ≥1 medical claim with a relevant ICD-9/10-CM diagnosis code. SLE disease severity (mild, moderate, and severe) and proportion of patients with flares by severity (mild, moderate, and severe) in the pre- and post-index date periods were identified using published algorithms.36–38

HCRU outcomes encompassed inpatient admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, physician office visits, outpatient/other ancillary visits, and medication use, and were assessed during the pre- and post-index date periods. A list of the medications considered to be SLE-related is available in Supplementary material (Supplementary Table). All-cause healthcare costs included medical (inpatient admissions, ED visits, physician office visits, and outpatient/other ancillary visits) and pharmacy costs, and were assessed in the pre- and post-index date periods. Cost included actual reimbursements paid by health plans plus any patient cost-sharing in the form of deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance for each medical or prescription encounter incurred. All cost estimates were adjusted for inflation to 2018 USD$ using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

Statistical analyses

All study measures were summarized descriptively, including frequency distributions for categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Pre- and post-index date period outcome comparisons were performed using paired t-tests (parametric) or Wilcoxon signed rank tests (non-parametric) for comparisons of means, and Chi-squared tests for comparisons of proportions. Healthcare costs were analyzed using a multivariable generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and log link, adjusted for covariates (age categories, sex, geographic region, year of index date, pre-index date CCI score, pre-index date quartile of total healthcare costs) and presented using least-squares means estimates. Statistical significance was evaluated at the α = 0.05 level. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

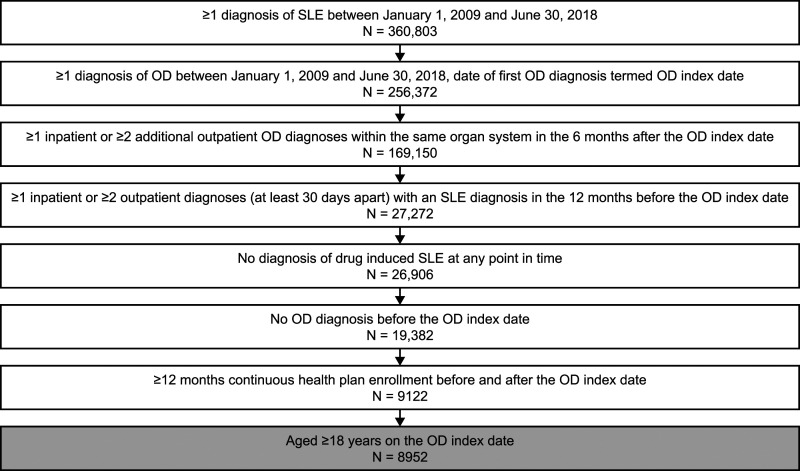

The initial population with a claim for SLE between 1 January 2009 and 30 June 2018 consisted of 360,803 patients. Of these, 9122 patients had at least 12 months continuous health plan enrollment both during the pre- and post-index periods. A total of 8952 patients met inclusion criteria and qualified for this analysis (Figure 2). At the index date, the mean (SD) age of patients was 46.4 (12.2) years, with 92% of patients being female (Table 1). The mean (SD) CCI score was significantly lower in the pre-index date period compared with the post-index date period (2.0 [1.1] vs 2.5 [1.6]; p < 0.0001), as was the SLE-adjusted CCI score (0.8 [1.7] vs 1.8 [2.9]; p < 0.0001). The incidences of the most common CCI conditions (i.e. hypertension, depression, and chronic pulmonary disease) were also less frequent during the pre- versus post-index date period.

Figure 2.

Patient selection. OD, organ damage; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline.

| Characteristic | Patients with SLE and organ damage (N = 8952) |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age at index date | 46.4 (12.2) |

| Female (%) | 92.0 |

| Geographic region (%) | |

| Northeast | 23.5 |

| South | 38.2 |

| Midwest | 24.4 |

| West | 11.9 |

| Missing | 2.1 |

| Common CCI conditions (%) | |

| Hypertension | 34.8 |

| Depression | 17.1 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 16.7 |

| Mean (SD) CCI score | 2.0 (1.1) |

| Mean (SD) SLE-adjusted CCI score | 0.8 (1.7) |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Organ damage and systemic lupus erythematosus severity

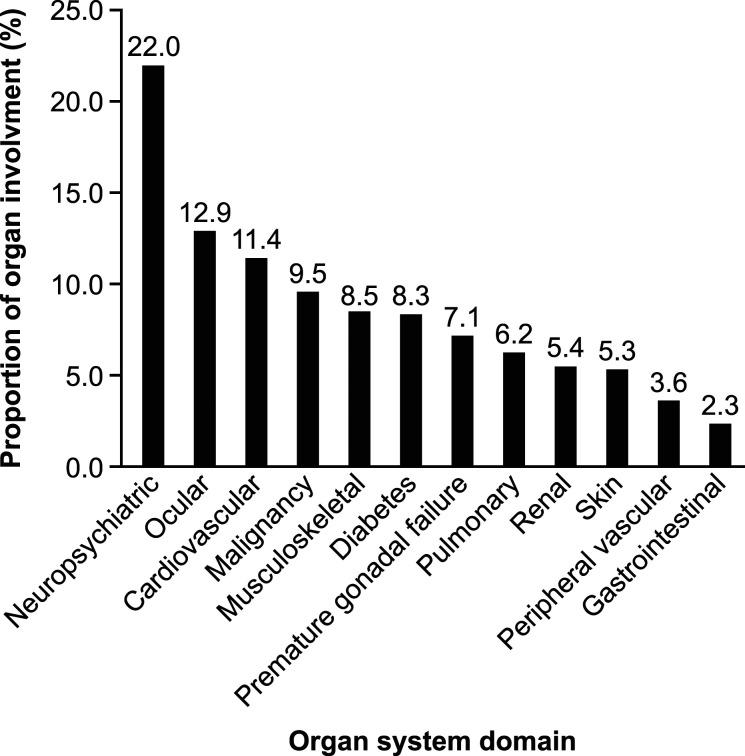

The most common sites of organ damage involvement at the index date were neuropsychiatric (22.0%), ocular (12.9%), and cardiovascular (11.4%), with a mean (SD) of 1.0 (0.2) sites of organ involvement (Figure 3). Significantly lower SLE severity was recorded during the pre-index date period (p < 0.0001), with 32.3%, 57.9%, and 9.8% of patients rated as mild, moderate and severe compared with 19.8%, 58.6%, and 21.6% during the post-index date period.

Figure 3.

Sites of organ damage by SDI domains observed on the index date. SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology (SLICC/ACR) Damage Index.

Systemic lupus erythematosus flare episodes

The proportion of patients with no or ≥1 mild flare episodes was greater during the pre- versus post-index date period (13.7% vs 9.6%; 63.7% vs 60.5%, respectively; p < 0.0001) while the number of patients experiencing ≥1 moderate or ≥1 severe flare episodes was lower in the pre- versus post-index date period (64.0% vs 75.1%; 10.8% vs 17.0%, respectively; p < 0.0001).

Healthcare resource utilization

The proportion of patients with an inpatient or outpatient hospital visit was significantly lower in the pre-index date period compared with the post-index date period (18.4% vs 25.9% and 79.3% vs 84.7%, respectively; both p < 0.0001). The proportion of ED visits was only marginally lower in the pre-index date period compared with the post-index date period (24.5% vs 26.5%; p = 0.003) (Table 2). Nearly all patients had an office visit in both the pre- and post-index date periods (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall HCRU and SLE-related medication patterns by patients with organ damage across all settings pre- and post-index dates.

| Patient visits by type | Pre-index (N = 8952) | Post-index (N = 8952) |

|---|---|---|

| Inpatient visits, n (%) | 1646 (18.4) | 2320 (25.9) |

| Number of visits a , mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (1.1) |

| Length of stay, mean (SD) | 1.2 (4.3) | 2.7 (13.6) |

| Emergency department visits, n (%) | 2189 (24.5) | 2376 (26.5) |

| Number of claims a , mean (SD) | 4.0 (18.7) | 5.0 (19.3) |

| Outpatient hospital visits, n (%) | 7096 (79.3) | 7585 (84.7) |

| Number of claims a , mean (SD) | 26.3 (37.7) | 39.1 (59.0) |

| Office visits, n (%) | 8820 (98.5) | 8836 (98.7) |

| Number of claims a , mean (SD) | 38.4 (37.5) | 48.7 (49.4) |

| Other outpatient care b , n (%) | 6081 (67.9) | 6582 (73.5) |

| Number of claims a , mean (SD) | 16.5 (40.2) | 22.7 (52.5) |

| Pharmacy, n (%) | 7915 (88.4) | 7886 (88.1) |

| Number of claims a , mean (SD) | 34.7 (32.9) | 39.4 (36.0) |

| Medication, n (%) | ||

| Immunosuppressants | 2516 (28.1) | 2790 (31.2) |

| Antimalarials | 5231 (58.4) | 5033 (56.2) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 4392 (49.1) | 4319 (48.3) |

| IV Corticosteroids | 2676 (29.9) | 3097 (34.6) |

| NSAIDs | 3314 (37.0) | 3232 (36.1) |

HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; IV, intravenous; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

aNumber of visits and claims were measured across all patients, regardless of whether they had utilization in the care setting.

bOther outpatient care included visits in other care settings (e.g. home healthcare) and laboratory services, among others.

Systemic lupus erythematosus-related medications received

The most common SLE-related medications received during the pre-index date period were antimalarials (58.4%), followed by oral corticosteroids (49.1%) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; 37.0%) (mean[SD] SLE-related medication categories: 2.0[1.3]). This trend remained during the post-index date period (Table 2). Similar proportions of patients received oral corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressors, and NSAIDs during the pre- and post-index date periods, while fewer patients required intravenous corticosteroids in the pre-index date period compared with the post-index date period.

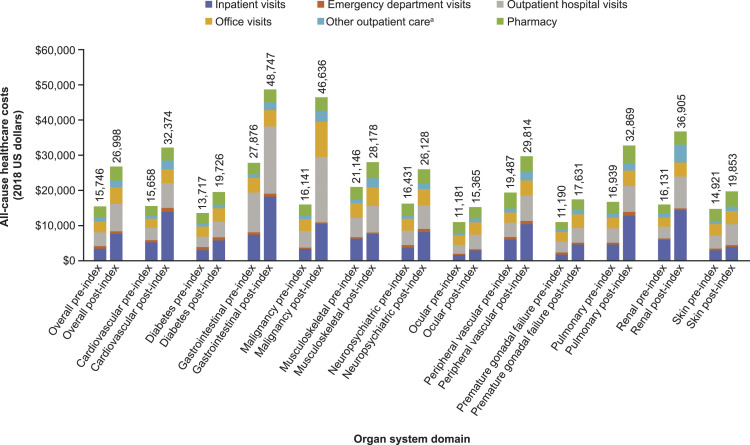

Healthcare costs

The mean (SD) post-index date total healthcare costs were 71% higher than the pre-index healthcare costs (US$26,998 (57,982) vs US$15,746 (29,637); p < 0.0001) (Figure 4). The largest component of costs in both periods was medical-related costs, with inpatient visits followed by outpatient visits, office visits, and pharmacy costs accounting for the largest percentage of all-cause costs during the post-index date period. The mean (95% confidence interval) adjusted healthcare costs for the post-index date period in patients with SLE and organ damage was US$20,169 (US$19,650, US$20,703). The highest total all-cause costs in the post-index date period by type of affected organ system domain were observed in the gastrointestinal domain (US$48,747), followed by malignancy (US$46,636), renal (US$36,905), pulmonary (US$32,869), and cardiovascular (US$32,374) domains (Figure 4). The smallest difference in costs between the pre- and post-index date periods was observed in patients with ocular organ damage (US$4184), while the largest difference in costs was observed in patients with malignancy organ damage (US$30,496) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

All-cause healthcare cost in patients with SLE and organ damage overall and categorized by affected organ system OD, organ damage; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. aOther outpatient care included visits in other care setting (e.g. home healthcare) and laboratory services, among others.

Discussion

Organ damage in patients with SLE is mainly driven by persistent disease activity and toxicity of standard therapies.9,12 The personal and economic burden associated with organ damage is substantial, being associated with poor health outcomes (e.g. negative impact in physical functioning, health-related quality of life, and life expectancy),21,39 and higher healthcare costs compared with patients with less severe damage.30,40

Our observational retrospective study provides important insights into the burden of SLE-associated organ damage across multiple organ domains in adult patients with SLE in real-world settings in the USA. Analysis of administrative claims data before and after diagnosis of the first site of organ damage demonstrated a substantial increase in annual HCRU and costs in patients with SLE who developed organ damage.

This study found that 92% of patients with SLE who developed organ damage were female and that the mean age at index was 46.4 years. Similar demographics were reported in previous retrospective administrative claims studies that evaluated adult patients with SLE covered by Medicaid 37 or in the MarketScan database that included Medicaid and commercial coverage. 41 The most common sites of organ damage at the index date were neuropsychiatric, followed by ocular and cardiovascular domains. In contrast with previous findings, 7 lower rates were observed for other common sites of organ damage, such as skin, musculoskeletal, and gastrointestinal. It is possible that these differences are due to our analysis assigning patients to organ system domains based on their diagnoses on the index date but patients may have qualified for other categories after the index date, which was not captured in our analysis.

The majority of patients (90.4%) had a flare episode during the 12-months post-index date period and there was a significant increase in disease severity versus the pre-index date period, which is in line with previous studies.42,43 Clarke et al. 41 reported significantly higher healthcare costs for patients with moderate and severe SLE compared with those with mild SLE. Additionally, increases in the frequency and severity of flares as well as greater disease severity were found to directly correlate with higher healthcare cost in the MarketScan databases between 2005 and 2014.44,45

The total all-cause healthcare costs substantially increased by 71% during the post-index date period (US$26,998) compared with the pre-index date period (US$15,746). Kan et al. 37 estimated an average of US$18,839 annual healthcare costs in patients with SLE, while other studies reported costs up to 3-fold higher among patients with SLE,41,46 depending on SLE severity and payer type. Lowest costs were observed among patients with mild SLE covered by commercial insurers, while highest costs were observed among patients with moderate or severe SLE covered by Medicaid. 41 Differences in the absolute healthcare costs between our analysis and previous studies may be reflective of differing patient populations analyzed. Our study evaluated patients with newly diagnosed organ damage. Therefore, our study population likely represents a healthier population than that included in previous analyses, which have used the transition from one disease severity stage as the index event, so patients in those studies may have had established organ damage.37,41,46 The overall rate of HCRU increased after the index date, with the significant difference in all-cause costs between the pre- versus post-index date periods being largely driven by higher rates of inpatient and outpatient hospital visits during the post-index date period.

Across all 12 organ system domains based on the SDI, costs after the index date ranged from US$15,365 to US$48,747. The highest costs in the post-index date period were associated with gastrointestinal, malignancy, renal, and pulmonary organ damage, with the largest difference in costs between the pre- and post-index date periods being observed in patients with malignancy. The lowest costs in the post-index date period were associated with ocular, premature gonadal failure, diabetes, and skin with the smallest difference in costs between pre- and post-index being observed in patients with ocular organ damage. To our knowledge, this is the first study in the USA to evaluate healthcare costs by type of organ damage.

Patients were most commonly treated with antimalarials, oral corticosteroids, and NSAIDs during the pre- and post-index period. Although corticosteroids are widely used in the treatment of SLE, long-term use is associated with organ damage, with tapering of the corticosteroid dose recommended in clinical guidelines to reduce the deleterious effects.1,7 In contrast, antimalarial drugs and belimumab, a human immunoglobulin G1 lambda monoclonal antibody, can help prevent organ damage. Antimalarial use has been associated with a reduced risk of new organ damage and progression of organ damage in patients with SLE compared with patients with SLE who did not receive antimalarials.27,47 Belimumab has been extensively studied in clinical trials and results from long-term Phase 3 studies for up to 8 years have demonstrated a lower incidence of organ damage in patients with SLE treated with belimumab plus standard therapy versus standard therapy.48–50 Propensity score-matched comparative analysis over a 5-year period also demonstrated a smaller increase in SDI score and a reduction in the progression of organ damage in patients treated with belimumab plus standard therapy compared with those receiving standard therapy only. 33 Given the economic burden of organ damage associated with SLE,10,18 early management with treatments that reduce the risk of organ damage have the potential to substantially reduce costs as well as improve outcomes.

Although administrative claims data provide valuable real-world information, there are a number of challenges and limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Because organ damage measured by the SDI is not captured in administrative claims data, the study relied on an algorithm to identify patients with organ damage. It is conceivable that patients may have had diagnoses for other organ damage domains after the index date, which were not recorded in our analysis and that would likely be associated with greater HCRU and costs. Furthermore, the identification of disease severity and flares through algorithms has known limitations,36–38 including relying on the use of healthcare services and prescriptions for SLE medications. A further limitation is that race/ethnicity data were not available in this data set, although both are known to be predictors of organ damage. Similarly, the lack of long-term dosage information and cumulative dose exposure for corticosteroids restricts assessment of the effects of long-term corticosteroid treatment on organ damage and associated costs. Certain aspects of healthcare patterns can be measured using administrative claims databases, such as pharmacy, office, inpatient, ED, and outpatient hospital visits. However, the limited information on socioeconomic aspects and lack of mortality and clinical data prevented an in-depth analysis of the relationship between organ damage-related costs and covariates such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status education, and SLE disease severity. Furthermore, since the database uses ICD codes to determine diagnoses, inaccuracies or misclassification bias may have occurred. An additional caveat of this study is the potential bias toward a healthier population of patients with SLE, as all patients evaluated in this study were required to have at least 24 months of continuous health plan enrollment and to be newly diagnosed with organ damage. As such, those patients who died within the 24-month period (e.g. from acute cardiovascular events or end-stage kidney disease) would have been excluded from the study. Finally, as the study population included only patients with commercial insurance, caution is advised when generalizing these data to a wider population.

Conclusion

Organ damage in patients with SLE is associated with increased SLE severity, frequency, and severity of flares, substantially greater HCRU and higher costs in the 12 months following the first observed organ damage diagnosis. These findings suggest that preventing organ damage may reduce the burden for patients with SLE and healthcare providers, further encouraging the development of new therapies that reduce or prevent SLE-related organ damage.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-lup-10.1177_09612033211073670 for An evaluation of costs associated with overall organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States by Christopher F Bell, Mayank R Ajmera and Juliana Meyers in Lupus

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Benjamin Wu and Joan Von Feldt (former employees of GlaxoSmithKline [GSK]) for assistance with protocol development and study conduct. Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including development of the initial draft based on author direction, assembling tables and figures, collating authors’ comments, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Katalin Bartus, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, part of Fishawack Health, and was funded by GSK.

Authors’ contributions: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and data analysis or interpretation.

The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

All authors had full access to the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: CFB is an employee of GSK and holds stocks and shares in the company. MRA and JM are employees of RTI Health Solutions. RTI Health Solutions received funding from GSK to conduct this analysis.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by GSK (GSK study 208380).

Data availability statement: All data required for interpretation of these results is included in this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Christopher F Bell https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6413-2537

References

- 1.Kuhn A, Bonsmann G, Anders HJ, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015; 112: 423–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. New Engl J Med 2008; 358: 929–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izmirly PM, Wan I, Sahl S, et al. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in New York county (Manhattan), New York: the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69: 2006–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izmirly PM, Parton H, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States: estimates from a meta-analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021; 73: 991–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nusbaum JS, Mirza I, Shum J, et al. Sex differences in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mayo Clinic Proc 2020; 95: 384–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge MJ, et al. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Rheumatology 2017; 56: 1945–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers SA, Allen E, Rahman A, et al. Damage and mortality in a group of British patients with systemic lupus erythematosus followed up for over 10 years. Rheumatology 2009; 48: 673–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segura BT, Bernstein BS, McDonnell T, et al. Damage accrual and mortality over long-term follow-up in 300 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in a multi-ethnic British cohort. Rheumatology 2020; 59: 524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Ibañez D, et al. Evolution of disease burden over five years in a multicenter inception systemic lupus erythematosus cohort. Arthritis Care Res 2012; 64: 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mak A, Isenberg DA, Lau CS. Global trends, potential mechanisms and early detection of organ damage in SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013; 9: 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zonana-Nacach A, Barr SG, Magder LS, et al. Damage in systemic lupus erythematosus and its association with corticosteroids. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43: 1801–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fava A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and clinical management. J Autoimmun 2019; 96: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Sawah S, Zhang X, Zhu B, et al. Effect of corticosteroid use by dose on the risk of developing organ damage over time in systemic lupus erythematosus--the Hopkins lupus cohort. Lupus Sci Med 2015; 2: e000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petri M, Magder LS. Comparison of remission and lupus low disease activity state in damage prevention in a United States systemic lupus erythematosus cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70: 1790–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Cruz DP. Systemic lupus erythematosus. BMJ 2006; 332: 890–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bultink IE, Turkstra F, Dijkmans BA, et al. High prevalence of unemployment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: association with organ damage and health-related quality of life. J Rheumatol 2008; 35: 1053–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Björk M, Dahlström Ö, Wetterö J, et al. Quality of life and acquired organ damage are intimately related to activity limitations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015; 16: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau CS, Mak A. The socioeconomic burden of SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2009; 5: 400–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trager J, Ward MM. Mortality and causes of death in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2001; 13: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y, Ye DQ, Pan HF, et al. Influence of social support on health-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 2009; 28: 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murimi-Worstell IB, Lin DH, Nab H, et al. Association between organ damage and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e031850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero-Diaz J, Isenberg D, Ramsey-Goldman R. Measures of adult systemic lupus erythematosus: updated version of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG 2004), European Consensus Lupus Activity Measurements (ECLAM), Systemic Lupus Activity Measure, Revised (SLAM-R), Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire for population studies (SLAQ), Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K), and Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (SDI). Arthritis Care Research 2011; 63(Suppl 11): S37–S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arora S, Isenberg DA, Castrejon I. Measures of adult systemic lupus erythematosus: disease activity and damage. Arthritis Care Res 2020; 72(Suppl 10): 27–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39: 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Goldsmith CH, et al. The reliability of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40: 809–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Rahman P, et al. Accrual of organ damage over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatology 2003; 30: 1955–1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruce IN, O’Keeffe AG, Farewell V, et al. Factors associated with damage accrual in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) inception cohort. Ann Rheumatic Diseases 2015; 74: 1706–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taraborelli M, Cavazzana I, Martinazzi N, et al. Organ damage accrual and distribution in systemic lupus erythematosus patients followed-up for more than 10 years. Lupus 2017; 26: 1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiu YM, Chuang MT, Lang HC. Medical costs incurred by organ damage caused by active disease, comorbidities and side effect of treatments in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a Taiwan nationwide population-based study. Rheumatol Int 2016; 36: 1507–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barber MRW, Hanly JG, Su L, et al. Economic evaluation of damage accrual in an international systemic lupus erythematosus inception cohort using a multistate model approach. Arthritis Care Res 2020; 72: 1800–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidson JE, Fu Q, Rao S, et al. Quantifying the burden of steroid-related damage in SLE in the Hopkins lupus cohort. Lupus Sci Med 2018; 5: e000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durcan L, O’Dwyer T, Petri M. Management strategies and future directions for systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. The Lancet 2019; 393: 2332–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urowitz MB, Ohsfeldt RL, Wielage RC, et al. Organ damage in patients treated with belimumab versus standard of care: a propensity score-matched comparative analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: 372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB. The SLICC/ACR damage index: progress report and experience in the field. Lupus 1999; 8: 632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward MM. Development and testing of a systemic lupus-specific risk adjustment index for in-hospital mortality. J Rheumatol 2000; 27: 1408–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garris C, Jhingran P, Bass D, et al. Healthcare utilization and cost of systemic lupus erythematosus in a US managed care health plan. J Med Econ 2013; 16: 667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kan H, Guerin A, Kaminsky MS, et al. A longitudinal analysis of costs associated with change in disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Med Econ 2013; 16: 793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narayanan S, Wilson K, Ogelsby A, et al. Economic burden of systemic lupus erythematosus flares and comorbidities in a commercially insured population in the United States. J Occup Environ Med 2013; 55: 1262–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feld J, Isenberg D. Why and how should we measure disease activity and damage in lupus? La Presse Médicale 2014; 43: e151–e156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doria A, Gatto M, Zen M, et al. Optimizing outcome in SLE: treating-to-target and definition of treatment goals. Autoimmun Rev 2014; 13: 770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke AE, Yazdany J, Kabadi SM, et al. The economic burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in commercially- and medicaid-insured populations in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020; 50: 759–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonakdar ZS, Mohtasham N, Karimifar M. Evaluation of damage index and its association with risk factors in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Res Med Sci 2011; 16(Suppl 1): S427–S432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ugarte-Gil MF, Acevedo-Vásquez E, Alarcón GS, et al. The number of flares patients experience impacts on damage accrual in systemic lupus erythematosus: data from a multiethnic Latin American cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 1019–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang M, Desta B, Near A, et al. Frequency, severity and costs of flares increase with disease severity in newly diagnosed systematic lupus erythematous: a real-world cohort study, United States, 2004–2015. Abstract for the 2019. American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang M, Near A, Desta B, et al. Comorbidities, health care utilization, and cost of care in systematic lupus erythematous increase with disease severity during 1 year before and after diagnosis: a real-world cohort study in the united states, 2004–2015. Abstract for the 2019. American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murimi-Worstell IB, Lin DH, Kan H, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs of systemic lupus erythematosus by disease severity in the United States. J Rheumatol 2020; 23: 385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fessler BJ, Alarcón GS, McGwin G, Jr, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: XVI. Association of hydroxychloroquine use with reduced risk of damage accrual. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 1473–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Vollenhoven RF, Navarra SV, Levy RA, et al. Long-term safety and limited organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with belimumab: a Phase III study extension. Rheumatology 2020; 59: 281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruce IN, Urowitz M, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Long-term organ damage accrual and safety in patients with SLE treated with belimumab plus standard of care. Lupus 2016; 25: 699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furie RA, Wallace DJ, Aranow C, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70: 868–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-lup-10.1177_09612033211073670 for An evaluation of costs associated with overall organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States by Christopher F Bell, Mayank R Ajmera and Juliana Meyers in Lupus