Abstract

Abortion is legal in South Africa, but negative abortion attitudes remain common and are poorly understood. We used nationally representative South African Social Attitudes Survey data to analyze abortion attitudes in the case of fetal anomaly and in the case of poverty from 2007 to 2016 (n = 20,711; ages = 16+). We measured correlations between abortion attitudes and these important predictors: religiosity, attitudes about premarital sex, attitudes about preferential hiring and promotion of women, and attitudes toward family gender roles. Abortion acceptability for poverty increased over time (b = 0.05, p < .001), but not for fetal anomaly (b = −0.008, p = .284). Highly religious South Africans reported lower abortion acceptability in both cases (Odds Ratio (OR)anomaly = 0.85, p = .015; ORpoverty = 0.84, p = .02). Premarital sex acceptability strongly and positively predicted abortion acceptability (ORanomaly = 2.63, p < .001; ORpoverty = 2.46, p < .001). Attitudes about preferential hiring and promotion of women were not associated with abortion attitudes, but favorable attitudes about working mothers were positively associated with abortion acceptability for fetal anomaly ((ORanomaly = 1.09, p = .01; ORpoverty = 1.02, p = .641)). Results suggest negative abortion attitudes remain common in South Africa and are closely tied to religiosity, traditional ideologies about sexuality, and gender role expectations about motherhood.

Keywords: Abortion, attitudes, reproductive health, South Africa

Introduction

Negative abortion attitudes are common in South Africa and can create barriers to safe abortion care, but evidence on abortion attitudes is limited to sub-national, qualitative, and cross-sectional studies. Prior research suggests abortion beliefs and attitudes can contribute to stigmatizing community norms, which increase women’s fears about losing confidentiality and experiencing discrimination if they have an abortion (Macleod, Sigcau, and Luwaca 2011; Varga 2002). Unsupportive attitudes among health workers can also contribute to fewer abortion providers and clinics, longer distances to care, and lower quality of care including judgment and discrimination of patients (Harries et al. 2014; Harries, Stinson, and Orner 2009). Negative abortion attitudes among family members and partners can lead to isolation and conflict as women navigate pregnancy-related decisions (Gresh and Maharaj 2014; Varga 2002). Finally, negative abortion attitudes can contribute to women’s own ambivalence and internalized shame, which can delay care-seeking and create barriers to safe abortion care (Gresh and Maharaj 2014; Harries et al. 2007; Varga 2002).

Existing evidence on South African abortion attitudes – along with research from other parts of the world (Jelen 2015; Jelen and Wilcox 2003) – suggests that religion, attitudes and norms about sexuality, and ideologies about gender equality might play important roles in abortion attitude formation. Macleod, Sigcau, and Luwaca (2011) conducted focus groups about abortion and culture with rural-dwelling South Africans, and participants often referred to religion, scripture, and gender norms. For example, many participants believed the Bible categorizes abortion as sinful murder. Participants also described women who had abortions as witches, adulterers, and unfit for marriage. In Varga’s (2002) mixed methods study of adolescents in KwaZulu-Natal and in a qualitative study of Western Cape health workers by Harries, Stinson, and Orner (2009), the research teams found that traditional expectations of sexuality contribute to negative abortion attitudes and norms. This included disapproval of adolescent sexuality and pregnancy in general, and equating unplanned pregnancy with sexual promiscuity and irresponsibility. At the same time, survey research in South Africa has produced mixed evidence of quantitative relationships between abortion attitudes, religiosity, gender equality, and sexuality norms. In a survey of undergraduate females in South Africa, Patel and Myeni (2008) found 22% of religious students would consider an abortion, 47% would not consider an abortion, and 31% were uncertain compared to 27%, 53%, and 20% of students who were not religious or neutral on religion. The authors did not statistically test these differences, but they concluded that conservative personal morality, rather than religiosity, might underlie student’s attitudes toward abortion. From their analysis of a national South African survey in 2013, Mosley et al. (2017) found no differences in abortion acceptability by religious denomination or between non-religious and religious groups. In another cross-national study by Mosley et al. (2019), the researchers did find that abortion acceptability was higher among South Africans that were more accepting of premarital sex, but this was not the focus of the study or fully explored. Using the Attitudes Toward Women scale among male and female undergraduates, Patel and Johns (2009) found that gender role attitudes were not related to abortion attitudes. On the other hand, Mosley et al. (2019) found greater abortion acceptability among South Africans who endorsed non-traditional gender norms related to childrearing and women working outside the home.

Each of these complex concepts – abortion, religiosity, premarital sex, and gender equality – has been fraught with challenges and controversies over the past 25 years of South African democracy. Understanding the historical and sociopolitical context surrounding these topics is crucial. South Africa’s constitution is considered one of the most progressive legal frameworks for sexual and reproductive health, but those policies are not equally translated into practice (Cooper et al. 2004; Hodes 2013; Patel and Johns 2009; Trueman and Magwentshu 2013). Sweeping changes in legislation have triggered national human rights conversations about gender equality, sexuality, and reproduction. For example, soon after South Africa’s first democratic government officially overcame the Apartheid regime in 1994, a coalition of policy-makers, health professionals, and women’s advocates began to mobilize toward legalization of abortion (Hodes 2013). This coalesced with broader international movements toward reproductive health and rights including legal abortion (Cooper et al. 2004). There is not much evidence of broad-based support for abortion within the anti-Apartheid movement, however, and many within the African National Congress (South Africa’s majority political party) strongly opposed or were ambivalent about abortion. Nevertheless, the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act was passed in 1996, which legalized abortion across South Africa. Heated debates ensued in medical journals and in public discourse (Hodes 2013).

At the same time, South Africa’s transformation to democracy produced an opportunity for wider discussion of gender equality and sexuality. Efforts to improve gender equality included legal protection for women under the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and South African leaders ratified the international Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination (Cooper et al. 2004). A new approach to contraception focused on women’s empowerment replaced the Apartheid-era population control approach to fertility, and free healthcare was promised to pregnant women (then, later, to all South Africans). Leaders also developed a rights-based approach to adolescent sexuality, which was intended to address high rates of adolescent pregnancy and to replace punitive approaches such as expelling pregnant students (Coovadia et al. 2009). All the while, conservative social norms (such as cultural and religious beliefs) and post-Apartheid structural deficits (such as uneven health infrastructure) impeded successful policy implementation (Cooper et al. 2004). For one, the majority of South Africans identify as Christian and religiosity remains an important cornerstone in the lives of most South Africans (Patel and Johns 2009; Trueman and Magwentshu 2013). Ultimately, progressive policies have not yet resulted in improved health outcomes as an estimated 58% of abortions in South Africa are still unsafe, half of the South African women have an extramarital pregnancy before the age of 21, and many South African women still lack access to an acceptable mix of contraceptives (Cooper et al. 2004; Coovadia et al. 2009).

For the current study, we sought to better understand how religiosity, sexuality attitudes, and gender equality attitudes might be related to South African abortion attitudes over the past decade. We asked these research questions:

How have abortion attitudes in South Africa changed over time, if at all?

How are abortion attitudes in South Africa related to religiosity, attitudes toward sexuality, and attitudes toward gender equality, if at all?

How have the effects of religiosity, sexuality attitudes, and gender equality attitudes changed over time, if at all?

Methods

Study sample

We combined and analyzed data from the South African Social Attitudes Surveys (SASAS) in 2007 through 2016 (excluding 2010 and 2012 when necessary variables were not available), which gave us a total sample of 20,711 respondents. The SASAS has been conducted annually since 2003 with an average of 3,500–7,00 respondents each year (Human Sciences Research Council 2015). Respondents must be 16 years of age or older and residents of South Africa (regardless of citizenship). The SASAS sample is drawn from the Human Sciences Research Council’s master sampling frame of 1,000 census enumeration areas (EAs). Each round of the SASAS consists of a subsample of 500 EAs that are stratified by province, urbanicity, and racial group. Within each stratum, the allocated number of EAs is drawn using probability proportional to size; then, within each selected EA, a pre-determined number of dwelling units is identified for inclusion. Interviewers then visit each unit, list all eligible persons in residence, and randomly select one respondent from that list for the in-person survey. Response rates for the SASAS have historically ranged from 80–90%.

Measures

Abortion attitudes

Abortion attitudes have been measured in various ways on quantitative surveys including prochoice to pro-life scales (Patel and Myeni 2008), support for abortion legality in various scenarios (Jelen and Wilcox 2003), and moral acceptability of abortion in various scenarios (Patel and Kooverjee 2009). The SASAS measured the moral acceptability of abortion in only two scenarios using standardized questions that have been implemented across social surveys in numerous countries (International Social Survey Programme 2019). The SASAS asked participants, “Do you personally think it is wrong or not wrong for a woman to have an abortion” in two cases: “if there is a strong chance of serious defect in the baby” and “if a family has a low income and cannot afford any more children.” These represent the two major categories of abortion scenarios: a so-called “medical” or “hard” reason for abortion and a so-called “social” or “soft” reason for abortion, respectively (Jelen and Wilcox 2003; Patel and Myeni 2008). The response categories were a 4-point Likert scale of “always wrong,” “almost always wrong,” “wrong only sometimes,” or “not wrong at all.”

Religion and religiosity

We measured religious denomination categorically as no religious affiliation, Christian Protestant, Catholic, or other religion. Religiosity was measured as the frequency of attendance at religious meetings and services, excluding special occasions such as funerals or baptisms. This operationalization of religiosity, while certainly not comprehensive, has been validated and used in previous studies of religiosity and social attitudes (Barkan 2014). Other components of religiosity including Biblical literalism and prayer frequency were not available on the SASAS. The response categories for the frequency of religious attendance varied slightly from year-to-year so we collapsed some categories in order to create a common scale, where higher score indicated higher religiosity: less than several times a year, several times a year, 1–3 times per month, and once a week or more.

Attitudes about sexuality

Attitudes toward sexual morality have been measured in a number of ways including attitudes toward premarital sex, homosexuality, and extramarital sex (Jelen 2015). Across surveys over time, the SASAS consistently asked participants, “Do you think it is wrong or not wrong if a man and a woman have sexual relations before marriage?” Responses were measured on a 4-point Likert scale of “always wrong,” “almost always wrong,” “wrong only sometimes,” or “not wrong at all.” We use this as a proxy of attitudes toward sexual morality.

Gender equality attitudes

The SASAS included one measure of gender equality attitudes on all surveys from 2007 to 2016, which was the level of agreement with preferential hiring and promotion of women. Previous research has demonstrated that attitudes toward preferential hiring and promotion of women constitute a proxy for gender equality attitudes, because preferential hiring and promotion of women is one component of gender equality efforts that seek to reduce inequality between men and women (Baunach 2002). This was measured on a 5-point Likert scale, which we collapsed into three categories: disagree, neutral, and agree. We conducted sensitivity analyses with all five response categories but found no differences in our results.

Researchers have also used attitudes toward gender roles as useful, albeit imperfect, proxies of gender equality (Jelen and Wilcox 2003; Patel and Johns 2009). The 2008 SASAS included six widely used and validated questions about gender roles in the household and family, so we conducted additional analyses on the 2008 data to better understand the effects of gender role attitudes on abortion acceptability. These were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree;” we reverse-coded the variables as needed so higher scores indicate higher agreement with gender equality between men and women. The survey items were: “A working mother can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work” (reverse-coded); “A child younger than 5 years is likely to suffer if his or her mother works;” “All in all, family life suffers when the woman has a full-time job;” “A job is alright, but what most women really want is a home and children;” “Being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for pay;” and “A man’s job is to earn money, a woman’s job is to look after the home and family.” We conducted principal component analysis (see Results below) to reduce these six variables into meaningful constructs.

Covariates

In the multivariable regression models, we also controlled for other relevant covariates related to our outcomes and predictors. These covariates were sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, age, urbanicity, political identity, marital status, attitudes toward income inequality, and province of residence.

Data analysis

We assessed univariate distributions, trends over time, bivariate relationships, and multivariable ordinal regression models of abortion attitudes and our predictors of interest: religiosity, attitudes about sex, and attitudes about gender equality. All analyses were conducted in Stata v. 14 using the svy commands to account for sample weights and stratification variables needed to produce a nationally representative sample. We first used descriptive statistics to describe the sociodemographics of our sample and the distribution of our dependent and independent variables of interest. Next, we analyzed the distribution of abortion attitudes, religiosity, attitudes toward premarital sex, and attitudes toward preferential hiring and promotion of women over time from 2007–2016. We tested for significant differences over time by using the ologit function in Stata14 with survey year as the independent variable (first as a continuous measure then again as a categorical measure) to calculate a bivariate beta coefficient and p-statistic. We chose this approach because traditional tests such as chi-squared are not compatible with complex sampling structures and weighted data. We then used the same ologit function to test for bivariate relationships between abortion attitudes, relationships between abortion attitudes, demographics, and our independent variables. We then conducted multiple ordinal logistic regression to examine the effect of our predictors and sociodemographic variables on abortion attitudes. Variables were included in the regression model if they were statistically significant at the bivariate level or if they had theoretical important to abortion attitudes (i.e., had been shown to associate with abortion attitudes in previous studies). Our research questions included changes in the effect of religiosity, sex attitudes, and gender attitudes over time, so we then tested survey year as a potential effect-modifying variable by adding an interaction term between the predictor (religiosity/sex attitudes/gender attitudes) and year (first as a continuous variable then as a categorical variable). We tested the significance of the modifying effect using an adjusted Wald test. We also assessed the fit of the multivariable models using Wald tests, since likelihood-ratio tests such as the Bayesian and Akaike information criteria (BIC and AIC) are incompatible with svy commands.

Results

Descriptive statistics

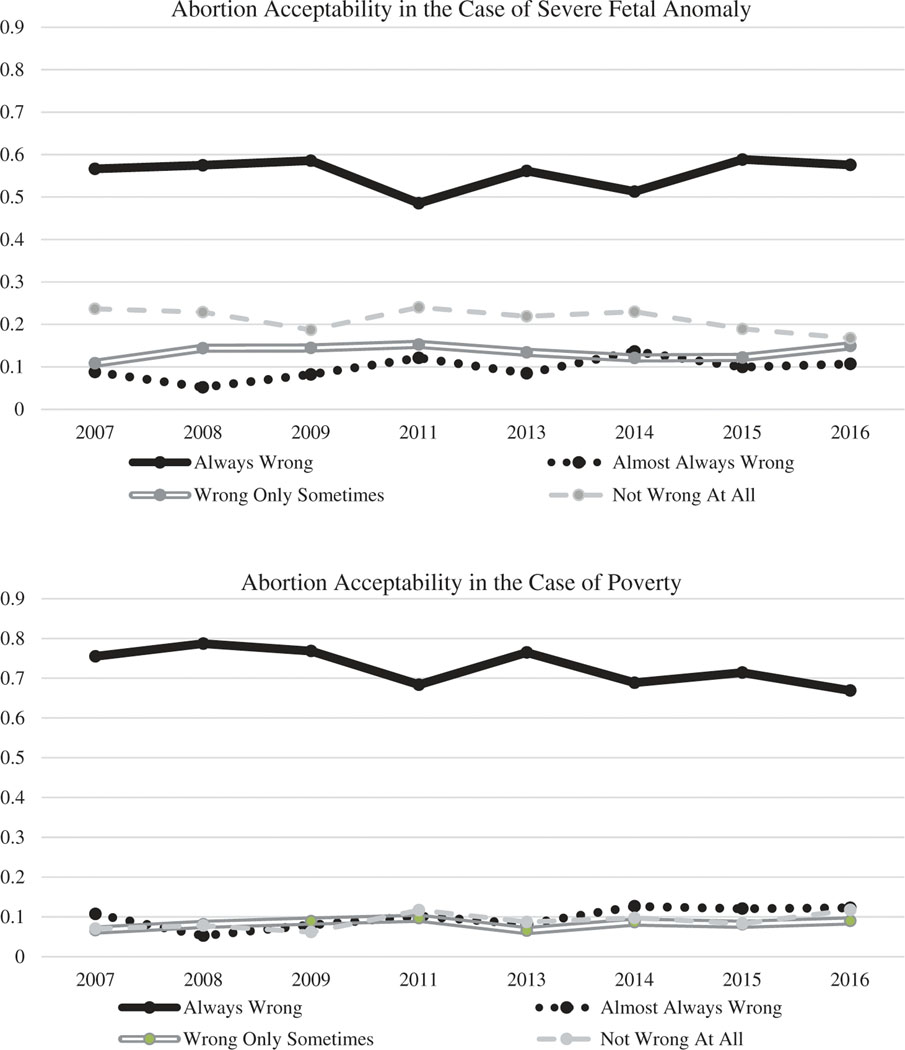

In the full sample from all years, 56% of South Africans surveyed said abortion is “always wrong” and 21% said it is “not wrong at all” in the case of severe fetal anomaly, while 73% said abortion is “always wrong” and 9% said it is “not wrong at all” if it’s because of poverty (other descriptive statistics can be seen in Table 1). From 2007 to 2016, there was no significant time trend overall in the acceptability of abortion for fetal anomaly (b = −0.008, p = .284), but acceptability was significantly higher in 2011 compared to 2007 (b = 0.23, p = .005) (see Figure 1). There was, however, a significant increase over time (b = 0.05, p < .001) in abortion acceptability for poverty. More specifically, acceptability of poverty-related abortion was significantly higher in 2011 (b = 0.39, p < .001) and 2014 (b = 0.33, p = .004) compared to 2007.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study sample from South African Social Attitudes Surveys 2006 to 2017 with additional gender role variables from 2008.

| Variable from 2007 to 2016 | Value/Category | Percentage | Variable from 2008 only | Value/Category | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sex | Female Male |

53% 47% |

A working mother can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work | Strongly disagree Disagree |

9% 21% |

| Race/Ethnicity | African Colored Indian/Asian White |

78% 9% 3% 10% |

A child younger than 5 years is likely to suffer if his or her mother works | Neither Agree Strongly agree Strongly agree |

6% 42% 21% 13% |

| Education | Primary or Less Some Secondary Completed Secondary Some Tertiary |

18% 39% 32% 10% |

Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

31% 13% 32% 11% |

|

| Monthly Household Income | Less than 1500 Rand 1501–7500 Rand 7501 Rand or More Refused/Do Not Know |

25% 37% 15% 23% |

All in all, family life suffers when the woman has a full-time job | Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree |

10% 24% 15% 37% |

| Age | Mean: 37.55 | SE: 0.18 | Strongly disagree | 15% | |

| Marital Status | Married Widow/Widower Divorced/Separated Never Married |

34% 7% 4% 55% |

A job is alright, but what most women really want is a home and children | Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree |

16% 36% 17% 19% |

| Political Identity | Conservative Moderate Liberal Do Not Know/Missing |

14% 22% 26% 38% |

Being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for pay | Strongly disagree Strongly agree Agree Neutral |

11% 10% 31% 17% |

| Urbanicity | Urban-Formal Urban-Informal Rural |

58% 10% 32% |

Disagree Strongly disagree Strongly agree |

27% 15% 15% |

|

| Religion | Not Religious Protestant Catholic Other |

16% 67% 5% 12% |

A man’s job is to earn money, a woman’s job is to look after the home and family | Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

18% 10% 29% 28% |

| Religiosity | Less than Several Times/Year | 24% | |||

| Several Times/Year | 14% | ||||

| 1 or 2–3 Times/Month | 22% | ||||

| Once a Week or More | 39% | ||||

| Province | Eastern Cape | 13% | |||

| Free State | 6% | ||||

| Gauteng | 23% | ||||

| KwaZulu-Natal | 20% | ||||

| Limpopo | 11% | ||||

| Mpumalanga | 7% | ||||

| Northern Cape | 2% | ||||

| Northwest | 6% | ||||

| Western Cape | 12% | ||||

Figure 1.

Trends in abortion attitudes for the cases of fetal anomaly and poverty in South Africa from 2007 to 2016.

From 2007 to 2016, 39% of respondents attended religious activities once a week or more, while 24% attended less than several times a year (Table 1). Over the period, religiosity significantly decreased (b = −0.02, p = .002) (Figure 2). Regarding attitudes about sex before marriage, 51% of South Africans surveyed said it was “always wrong,” but 27% said it was “not wrong at all.” Attitudes toward premarital sex became more lenient from 2007 to 2016 (b = 0.07, p > .001). Notably, there was a shift in premarital sex attitudes in 2011, when significantly more South Africans reported premarital sex is morally acceptable (b = 0.78, p < .001). The majority of respondents (70%) supported preferential hiring and promotion for women, while 17% disagreed with the initiatives. These attitudes were stable across the time period (b = −0.006, p = .515).

Figure 2.

Trends in religiosity, sex attitudes, and attitudes toward preferential hiring and promotion for women in South Africa from 2007 to 2016.

Multivariable regression models from 2007–2016

After controlling for covariates, temporal trends suggest that acceptability of abortion in the case of fetal anomaly decreased (Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.97, p = .001), while acceptability of abortion in the case of poverty increased (ORpoverty = 1.03, p = .003) (Table 2). The highest level of religiosity – attending once a week or more – was associated with decreased abortion acceptability in both cases (ORanomaly = 0.85, p = .015; ORpoverty = 0.83, p = .018). Religious denomination was not associated with abortion attitudes in either scenario. Compared to respondents who felt premarital sex is always wrong, individuals with more lenient sex attitudes reported higher abortion acceptability in both cases (ORanomaly = 2.64, p < .001; ORpoverty = 2.47, p < .001). Attitudes about preferential employment and hiring for women were not clearly related to abortion acceptability: only in the case of poverty, respondents who were neutral about preferential hiring and promotion of women reported higher abortion acceptability (ORpoverty = 1.28, p = .006).

Table 2.

Multivariable ordinal logistic regression models of abortion attitudes in the case of fetal anomaly and in the case of poverty from 2007 to 2016.

| Fetal Anomaly (N = 20,711) F = 18.38, p < .001 | Poverty (N = 20,711) F = 17.71, p < .001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| OR | p | SE | OR | p | SE | |

|

| ||||||

| Year | 0.97 | .001 | 0.01 | 1.03 | .003 | 0.01 |

| Religiosity (Reference: Less than several times a year) | ||||||

| Several Times a Year | 0.89 | .137 | 0.07 | 0.91 | .314 | 0.08 |

| 1–3 Times per Month | 0.97 | .695 | 0.07 | 0.95 | .555 | 0.08 |

| Once a Week or More | 0.85 | .015 | 0.06 | 0.83 | .018 | 0.06 |

| Premarital Sex Attitudes (Reference: Always Wrong) | ||||||

| Almost Always Wrong | 2.13 | <.001 | 0.14 | 2.65 | <.001 | 0.21 |

| Wrong Only Sometimes | 2.61 | <.001 | 0.15 | 2.65 | <.001 | 0.19 |

| Not Wrong At All | 2.64 | <.001 | 0.16 | 2.47 | <.001 | 0.17 |

| Preferential Hiring and Promotion for Women Attitudes (Referenc e: Disagree/Strongly Disagree) | ||||||

| Neutral | 1.01 | .856 | 0.07 | 1.28 | .006 | 0.12 |

| Agree/Strongly Agree | 1.04 | .533 | 0.07 | 1.15 | .075 | 0.09 |

| Female | 1.07 | .122 | 0.04 | 1.02 | .722 | 0.05 |

| Race/Ethnicity (Reference: African) | ||||||

| Colored | 1.10 | .185 | 0.08 | 0.82 | .025 | 0.07 |

| Indian | 1.43 | <.001 | 0.14 | 1.29 | .022 | 0.14 |

| White | 1.76 | <.001 | 0.14 | 0.92 | .4 | 0.09 |

| Education (Reference: Primary or Less) | ||||||

| Some Secondary | 1.26 | <.001 | 0.08 | 1.24 | .004 | 0.09 |

| Completed Secondary | 1.31 | <.001 | 0.09 | 1.45 | <.001 | 0.12 |

| Some Tertiary | 1.72 | <.001 | 0.15 | 1.70 | <.001 | 0.18 |

| Household Monthly Income | ||||||

| 1501–7500 Rand | 1.08 | .136 | 0.06 | 1.06 | .364 | 0.07 |

| More than 7500 Rand | 1.02 | .835 | 0.08 | 0.96 | .674 | 0.09 |

| Missing/Refused | 0.94 | .327 | 0.06 | 0.84 | .036 | 0.07 |

| Age | 1.00 | .366 | 0.002 | 1.00 | .347 | 0.002 |

| Urbanicity (Reference: Urban-Formal) | ||||||

| Urban-Informal | 0.84 | .075 | 0.08 | 1.04 | .692 | 0.11 |

| Rural | 0.94 | .305 | 0.06 | 1.04 | .572 | 0.07 |

| Religious Denomination (Reference: Not Religious) | ||||||

| Protestant | 1.10 | .199 | 0.08 | 1.03 | .739 | 0.09 |

| Catholic | 1.13 | .247 | 0.12 | 1.07 | .625 | 0.14 |

| Other | 1.13 | .197 | 0.11 | 1.01 | .916 | 0.11 |

| Political Identity (Reference: Conservative) | ||||||

| Moderate | 0.82 | .007 | 0.06 | 0.84 | .053 | 0.07 |

| Liberal | 1.00 | .995 | 0.07 | 1.05 | .598 | 0.09 |

| Don’t Know | 1.00 | .999 | 0.07 | 1.00 | .958 | 0.09 |

| Marital Status (Reference: Married) | ||||||

| Widowed/Widower | 0.93 | .391 | 0.08 | 0.87 | .178 | 0.09 |

| Divorced/Separated | 0.94 | .451 | 0.08 | 1.17 | .137 | 0.12 |

| Never Married | 0.93 | .162 | 0.05 | 1.01 | .895 | 0.06 |

| Income Differences are Too Large (Reference: Disagree/Strongly Disagree) | ||||||

| Neutral | 0.59 | <.001 | 0.07 | 1.06 | .677 | 0.15 |

| Agree/Strongly Agree | 0.71 | <.001 | 0.06 | 0.70 | .001 | 0.08 |

| Missing | 0.55 | .002 | 0.10 | 0.43 | <.001 | 0.10 |

Models also control for province of residence; significantly higher and lower odds italicized and bolded.

We used interaction terms and predicted probabilities to assess changes over time in the effects of sex attitudes, religiosity, and gender equity attitudes. The effects of sex attitudes significantly declined over time for abortion acceptability in the case of fetal anomaly (F = 5.47, p = .0007) and for poverty (F = 6.02, p = .0004). From 2007 to 2016, the effects of religiosity (Fanomaly = 2.37, p = .069; Fpoverty = 2.37, p = .069), and gender equality attitudes (Fanomaly = 0.63, p = .534; Fpoverty = 0.76, p = .466) on abortion acceptability remained stable over time in both the cases of fetal anomaly and poverty.

Gender role attitude analyses from 2008

The distribution of gender role attitudes in 2008 is presented in Table 1. The principal component analysis on these six variables suggested a two-factor solution (Eigenvalues 2.47 and 1.20). The four survey items about family life suffering when women work, women wanting a home and children more than employment, housewifehood being as fulfilling as employment, and expectations of men earning and women keeping the home all loaded sufficiently (>0.40) onto Factor 1, which we termed “attitudes about working women.” The survey items about potentially negative effects of working mothers and working mothers with preschoolers sufficiently loaded onto Factor 2, which we termed “attitudes about motherhood.”

We constructed the same multivariable regression models as described for the 2007–2016 trends, only we added the two new variables of attitudes about working women and attitudes about motherhood. The results are presented in Table 3, and we highlight the most important findings here. In the case of abortion due to fetal anomaly, respondents who endorsed egalitarian (more feminist) attitudes about motherhood were more likely to find abortion morally acceptable (OR = 1.09, p = .01), but this was not true for abortion in the case of poverty (OR = 0.93, p = .214). Attitudes about working women were not related to abortion attitudes in either scenario (ORanomaly = 1.00, p = .904; ORpoverty = 1.01, p = .823) in the multivariable models.

Table 3.

Multivariable ordinal logistic regression models of abortion attitudes in the case of fetal anomaly and in the case of poverty as predicted by gender role attitudes in 2008.

| Fetal Anomaly (N = 2,847) F = 6.67, p < .001 | Poverty (N = 2,850) F = 6.69, p < .001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| OR | p | SE | OR | p | SE | |

|

| ||||||

| Egalitarian attitudes toward working women | 1.00 | .904 | 0.02 | 0.99 | .510 | 0.02 |

| Egalitarian attitudes toward motherhood | 1.09 | .01 | 0.04 | 1.02 | .641 | 0.04 |

| Religiosity (Reference: Less than several times a year) | ||||||

| Several Times a Year | 0.97 | .884 | 0.19 | 1.12 | .658 | 0.28 |

| 1–3 Times per Month | 1.36 | .116 | 0.26 | 1.06 | .802 | 0.25 |

| Once a Week or More | 0.95 | .79 | 0.17 | 0.81 | .312 | 0.17 |

| Premarital Sex Attitudes (Reference: Always Wrong) | ||||||

| Almost Always Wrong | 1.91 | <.001 | 0.32 | 2.66 | <.001 | 0.66 |

| Wrong Only Sometimes | 2.86 | <.001 | 0.39 | 3.29 | <.001 | 0.59 |

| Not Wrong At All | 2.38 | <.001 | 0.35 | 3.59 | <.001 | 0.61 |

| Preferential Hiring and Promotion for Women Attitudes (Reference: Disagree/Strongly Disagree) | ||||||

| Neutral | 1.13 | .524 | 0.22 | 1.11 | .69 | 0.28 |

| Agree/Strongly Agree | 0.89 | .512 | 0.15 | 1.20 | .462 | 0.29 |

models also control for gender, race/ethnicity, education, household income, age, urbanicity, religious denomination, political identity, marital status, attitudes toward income inequality, and province of residence; significantly higher odds italicized and bolded.

Discussion

Results from the current study suggest that negative abortion attitudes remain common in South Africa, and they are closely tied to ideologies about sexuality, to religiosity, and to gender inequality – particularly social expectations of motherhood. Traditional attitudes toward premarital sex were the strongest covariate of negative abortion attitudes in our models, although the relative strength of that relationship has declined over the past decade as South Africans adopt more lenient attitudes toward sex before marriage. Notably, the increase in abortion acceptability in 2011 corresponded with a similar increase in the acceptability of premarital sex. South Africans with the highest levels of religiosity also reported more negative attitudes compared to less religious individuals, but the religious denomination was not influential. Attitudes toward preferential hiring and promotion of women were not clearly related to abortion acceptability, but in 2008 traditional social expectations about motherhood predicted more negative attitudes about abortion. Together, these factors interact and construct the sociocultural environments underlying abortion attitudes. Each must be closely considered and directly addressed to decrease abortion stigma and related health consequences in South Africa.

Abortion stigma is a social process that ascribes negative attributes to and discriminates against women who have abortions and the clinicians who serve them (Harris et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2009; Norris et al. 2011). It operates across multiple socio-ecological levels (from the individual level to the macro level) creating barriers to legal abortion services, which leads to unsafe abortion, preventable health complications, and maternal deaths (Singh et al. 2012; Trueman and Magwentshu 2013). Today, over half of the abortions in South Africa are unsafe, and abortion-related maternal mortality has been rising since 2007 (Singh et al. 2012; Trueman and Magwentshu 2013). Abortion stigma is predicated on the belief that abortion is morally wrong, so individual-level attitudes about abortion mortality could be important points of intervention to reduce negative health outcomes from abortion stigma. Previous research in South Africa has shown that women’s own attitudes about abortion can affect their reproductive decision-making by creating ambivalence and delaying abortion care (Gresh and Maharaj 2014; Harries et al. 2007; Varga 2002). Abortion attitudes among South African health-care providers have been shown to decrease the quality and accessibility of abortion services (Harries et al. 2014; Harries, Stinson, and Orner 2009). And aggregate-level abortion attitudes contribute to the community-level social norms that make women fearful of accessing abortion care through the formal sector (Gresh and Maharaj 2014; Macleod, Sigcau, and Luwaca 2011; Varga 2002). Ultimately, stigmatizing abortion attitudes can contribute to women’s own experiences of internalized stigma, the quality of care they receive, and the social environment in which they make pregnancy-related decisions.

Traditional ideologies of sexuality seem to be shifting over time and their influence on abortion attitudes is diminishing. However, abortion stigma interventions for women experiencing unintended pregnancy, abortion providers, and community members will nevertheless need to address disapproving community norms about premarital sex, adolescent sexual activity, and other nontraditional sexual behaviors. In other words, this will require abortion destigmatization and resiliency-building approaches for women and abortion providers that address attitudes about sex and sexuality more broadly in addition to attitudes about abortion, specifically. A guide for abortion education in community settings, written by International Planned Parenthood Federation (2016), stresses that effective abortion education occurs in the context of rights-based comprehensive sexuality education that encompasses relationships and sexuality more broadly. Notably, however, given the complex history and context of abortion, women’s rights, and feminism in South Africa, any interventions informed by feminist ideologies could be treated with suspicion and resistance. Appropriate and effective interventions for stigma reductions will need to be formulated and introduced with sensitivity toward and consideration of the contextual issues in South African communities.

While religiosity is not necessarily a modifiable factor, abortion stigma interventions will also need to address religious beliefs, including those that have become part of the secular South African cultural tradition (for example, pro-natalism). In the U.S., some scholars have advocated that reproductive justice can serve as a unifying platform for Christian communities (Peters 2018). Reproductive justice is a social theory and community organizing framework that advocates for the human rights to have children, to not have children, and to raise one’s children with health and dignity (Ross 2006). This framework directly addresses the social inequalities that underlie reproductive decisions, outcomes, and disparities including gender, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic oppression. Through her work as a progressive clergy member and religious scholar in the U.S. South, Peters found that by contextualizing abortion in the lived experiences and challenges of women’s lives – especially by highlighting the social and economic conditions that make childrearing impossible for many women – she is able to identify common values and reduce stigmatization among Christian communities. Nevertheless, public health professionals will again need to carefully consider the contextual issues in South African communities that could create suspicion and resistance to feminist-based interventions that are not informed by the history and sociopolitical dynamics of specific locations.

In our study, supportive attitudes toward preferential hiring and promotion for women were not clearly related to abortion acceptability, but respondents who endorsed more egalitarian attitudes about mothers working outside the home were more likely to find abortion morally acceptable. This suggests that gender ideology about the private rather than the public sphere underlies abortion attitudes. Interventions developed in South Africa such as Communities for Choice (Varkey and Ketlhapile 2001) could work to address patriarchal beliefs about women’s roles that underlie abortion stigma, for example by critically examining the social expectations of motherhood through the lens of power, autonomy, and social equality. Such educational interventions would, of course, need to be tailored to the unique histories and contexts of particular South African communities.

Our results also shed light on how abortion acceptability in the case of poverty seems to be increasing over the past decade, while acceptability for fetal anomaly has remained stable. From 2007 to 2016, attitudes toward abortion in the case of fetal anomaly did not change overall, although acceptability was higher in 2011 compared to all other years. For abortion in the case of poverty, acceptability did increase over time, and it was higher in 2011 and 2014, particularly. This could be an optimistic sign that recognizing a woman’s socioeconomic context might be becoming more accepted over time, while attitudes about fetal anomaly related abortion are harder to change. One explanation of the improved poverty-related abortion attitudes could be the passage of time since Apartheid, when unsafe abortion and abortion-related mortality were very high due to racialized poverty and illegality of abortion (Hodes 2013). More research is needed to understand what might have occurred during or immediately prior to the SASAS in 2011 and 2014 to increase abortion acceptability at the population level. One explanation might be the above-average increase in acceptability of premarital sex, which coincided with the 2011 increase in abortion acceptability. Another hypothesis we propose is increased awareness about unsafe abortion in 2011 following a national report by the South African Medical Research Council on abortion-related maternal mortality in 2010 (Osman 2011), but the changes in poverty-related abortion attitudes in 2014 are harder to explain. Further qualitative research could be valuable for identifying points for feasible intervention.

The current study has a number of strengths and limitations. Primarily, the data were collected with repeated, cross-sectional surveys and cannot be used to make claims of causality. All the relationships we observed in this study reflect bidirectional associations. At the same time, this is the first study to look at abortion attitudes over time, which allowed us to measure trends in abortion attitudes as well as assess changes in the relationships over time. Secondly, because we used secondary data we were limited by the variables available to us and were unable to use ideal measures for our constructs of interest including abortion acceptability, gender equality attitudes, and sexuality attitudes. We acknowledge that close-ended questions about complex topics such as abortion, social equality, and morality are limited, lack important nuance and context, and must be cautiously interpreted. Nevertheless, the standardized measures used by SASAS researchers enabled them to survey a nationally representative sample of South Africans, which allowed us to make inferences to the entire South African population.

Ultimately, our findings suggest that addressing negative abortion attitudes in South Africa requires direct attention to attitudes and norms of sexuality, religiosity, and gender equality. The examples described above demonstrate how interventions can effectively consider and address these factors in order to reduce abortion stigma. Moving forward, they could be carefully and thoughtfully adapted and implemented in the South African context, where abortion stigma remains a major driver of unsafe abortion and maternal mortality.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mosley’s research was supported by the NICHD Center grant to the University of Michigan Population Studies Center (P2CHD041028).

Funding

This research was supported in part by an NICHD center grant to the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan (P2CHD041028).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barkan SE 2014. Gender and abortion attitudes: Religiosity as a suppressor variable. Public Opinion Quarterly 78 (4):940–50. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfu047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baunach DM 2002. Progress, opportunity, and backlash: explaining attitudes toward gender-based affirmative action. Sociological Focus 35 (4):345–62. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2002.10570708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Morroni C, Orner P, Moodley J, Harries J, Cullingworth L, and Hoffman M. 2004. Ten years of democracy in South Africa: Documenting transformation in reproductive health policy and status. Reproductive Health Matters 12 (24):70–85. doi: 10.1080/14725843.2015.1009618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coovadia H, Jewkes R, Barron P, Sanders D, and Diane M. 2009. The health and health system of South Africa: Historical roots of current public health challenges. The Lancet, Health In South Africa 374:817–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60951-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresh A, and Maharaj P. 2014. Termination of pregnancy: Perspectives of female students in Durban, South Africa. African Population Studies 28 (1):681–90. doi: 10.11564/28-0-524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harries J, Cooper D, Strebel A, and Colvin CJ 2014. Conscientious objection and its Impact on abortion service provision in South Africa: A qualitative study. Reproductive Health 11 (16):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries J, Orner P, Gabriel M, and Mitchell E. 2007. Delays in seeking an abortion until the second trimester: A qualitative study in South Africa. Reproductive Health 4 (1):7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries J, Stinson K, and Orner P. 2009. Health care providers’ attitudes towards termination of pregnancy: A qualitative study in South Africa. BMC Public Health 9 (1):296. doi: 10.1186/14712458-9-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LH, Debbink M, Martin L, and Hassinger J. 2011. Dynamics of stigma in abortion work: Findings from a pilot study of the providers share workshop. Social Science & Medicine 73 (7):1062–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes R. 2013. The medical history of abortion in South Africa, c. 1970–2000. Journal of Southern African Studies 39 (3):527–42. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2013.824770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Human Sciences Research Council. 2015. South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS). http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/departments/sasas. [Google Scholar]

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. 2016. How to educate about abortion: A guide for peer educators, teachers and trainers. International Planned Parenthood Federation. https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/2016-05/ippf_peereducationguide_abortion_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- International Social Survey Programme. 2019. History of the international social survey programme. http://w.issp.org/about-issp/history/. [Google Scholar]

- Jelen TG 2015. Gender role beliefs and attitudes toward abortion: A cross-national exploration. Journal of Research in Gender Studies 5:11. [Google Scholar]

- Jelen TG, and Wilcox C. 2003. Causes and consequences of public attitudes toward abortion: A review and research agenda. Political Research Quarterly 56 (4):489–500. doi: 10.1177/106591290305600410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Hessini L, Ellen MH, and Mitchell. 2009. Conceptualising abortion stigma. Culture, Health & Sexuality 11 (6):625–39. doi: 10.1080/13691050902842741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod CI, Sigcau N, and Luwaca P. 2011. Culture as a discursive resource opposing legal abortion. Critical Public Health 21 (2):237–45. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2010.492211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley EA, Anderson BA, Harris LH, Fleming PJ, and Schulz AJ 2019. April. Attitudes toward abortion, social welfare programs, and gender roles in the U.S. and South Africa. Critical Public Health 1–16. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2019.1601683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley EA, King EJ, Schulz AJ, Harris LH, De Wet N, and Anderson BA 2017. Abortion attitudes among South Africans: Findings from the 2013 social attitudes survey. Culture, Health & Sexuality 19 (8):918–33. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1272715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris A, Bessett D, Steinberg JR, Kavanaugh ML, De Zordo S, and Becker D. 2011. Abortion stigma: A Reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Women’s Health Issues 21 (3):S49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman S. 2011. women’s reproductive health in South Africa- a paradox. NGO Pulse, November 7. http://www.ngopulse.org/blogs/women-s-reproductive-health-south-africa-paradox. [Google Scholar]

- Patel CJ, and Johns L. 2009. Gender role attitudes and attitudes to abortion: Are There gender differences? The Social Science Journal 46 (3):493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2009.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel CJ, and Kooverjee T. 2009. Abortion and contraception: Attitudes of South African University students. Health Care for Women International 30 (6):550–68. doi: 10.1080/07399330902886105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel CJ, and Myeni MC 2008. Attitudes toward abortion in a sample of South African Female University students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38 (3):736–50. doi: 10.1111/j.15591816.2007.00324.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RT 2018. Trust women: A progressive christian argument for reproductive justice. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ross L. 2006. Understanding Reproductive Justice. Atlanta, Georgia: SisterSong. http://www.trustblackwomen.org/our-work/what-is-reproductive-justice/9-what-is-reproductive-justice. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Sedgh G, Bankole A, Hussain R, and London S. 2012. Making abortion services accessible in the wake of legal reforms: A framework and six case studies. Guttmacher Institute. http://clacaidigital.info:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueman KA, and Magwentshu M. 2013. Abortion in a progressive legal environment: The need for vigilance in protecting and promoting access to safe abortion services in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health 103 (3):397–99. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga CA 2002. Pregnancy termination among South African Adolescents. Studies in Family Planning 33 (4):283–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varkey SJ, and Ketlhapile M. 2001. Communities for choice: A manual to improve access to abortion services. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Witwatersrand School of Public Health Women’s Health Project. [Google Scholar]