Abstract

Aims

The aim of the study was to assess the provision of dietetic services for coeliac disease (CD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods

Hospitals within all National Health Service trusts in England were approached (n=209). A custom-designed web-based questionnaire was circulated via contact methods of email, post or telephone. Individuals/teams with knowledge of gastrointestinal (GI) dietetic services within their trust were invited to complete.

Results

76% of trusts (n=158) provided GI dietetic services, with responses received from 78% of these trusts (n=123). The median number of dietitians per 100 000 population was 3.64 (range 0.15–16.60), which differed significantly between regions (p=0.03). The most common individual consultation time for patients with CD, IBS and IBD was 15–30 min (43%, 44% and 54%, respectively). GI dietetic services were delivered both via individual and group counselling, with individual counselling being the more frequent delivery method available (93% individual vs 34% group). A significant proportion of trusts did not deliver any specialist dietetic clinics for CD, IBS and IBD (49% (n=60), 50% (n=61) and 72% (n=88), respectively).

Conclusion

There is an inequity of GI dietetic services across England, with regional differences in the level of provision and extent of specialist care. Allocated time for clinics appears to be insufficient compared with time advocated in the literature. Group clinics are becoming a more common method of dietetic service delivery for CD and IBS. National guidance on GI dietetic service delivery is required to ensure equity of dietetic services across England.

Keywords: coeliac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, diet

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this topic

Little is currently known on the provision of gastroenterology dietetic services in England.

What this study adds

This is the first study assessing the provision of gastroenterology dietetic services as a whole in England, highlighting the variability of dietitian numbers across England, and the use of group clinics to deliver services. Allocated time for clinics appears to be insufficient, with variability in specialist dietetic care delivery across England.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

This study highlights the need for national guidance for the optimal delivery of gastrointestinal dietetic services, to ensure equity of access. Also, a shift to group clinics is likely to help cope with demand.

Introduction

Since the inception of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK in 1948, there have been huge changes in population demographics, with an increase in chronic long-term conditions. The role of the dietitian has become established over time, with a growing recognition on nutritional interventions on health outcomes.1

While there has been an increasing demand for dietitians, little is known on the provision of gastrointestinal (GI) dietetic services in England. The last survey assessing the provision of dietetic services was in 2007, where dietetic provision was only one-third of what was recommended by the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for coeliac disease (CD). This study focused on dietetic services in CD management alone, with a questionnaire completion rate of 38%.2

Dietetic input is essential in GI services. In CD, dietetic input can help educate individuals on a gluten-free diet, monitor adherence, identify hidden sources of gluten, healthy gluten-free grains and ensure adequate fibre and nutrient intake.3 There has been a rapid expansion in the role of dietary therapies in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with dietitians required at the forefront to deliver these therapies effectively.4 Current diets being implemented by dietitians for IBS include general dietary advice and the low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyps (FODMAPs) diet, as advised by the British Dietetic Association (BDA).5 Nutritional input from dietitians is also essential in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with dietitians required to prevent and treat malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies, as well as the prevention of osteoporosis.6

To our knowledge, there have been no studies assessing the provision of gastroenterology dietetic services as a whole in England to date. In view of this, the aim of the study was to assess the current provision of dietetic services in CD, IBS and IBD.

Methods

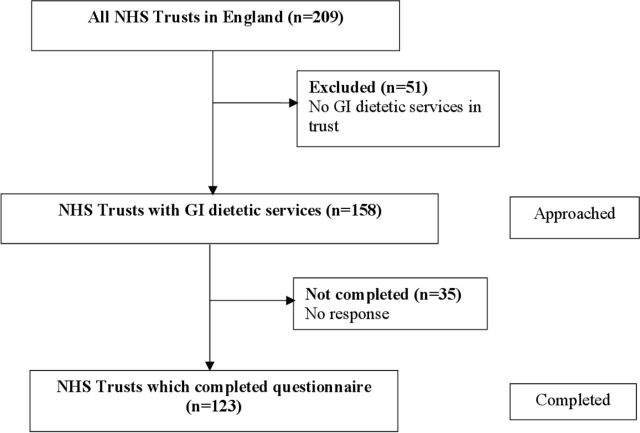

Hospitals within all England NHS trusts were approached between February 2019 and July 2019, with all NHS trusts within England being identified from the NHS England website (https://www.england.nhs.uk/). Following this, dietetic departments within all England NHS trusts were approached, either via telephone, letter or email. Individuals/teams of dietitians with knowledge of GI services within their trusts were invited to complete a custom-designed web-based questionnaire, or a paper version if unable to complete electronically. Trusts that did not provide any gastroenterology dietetic services were excluded (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for participants during trial. GI, gastrointestinal; NHS, National Health Service.

Questions asked included time allocated to GI services, grade of dietitian responsible for GI services, setting in which patients are seen, waiting times, average consultation time and teaching methods used.

All data collected were maintained confidentially, with data being analysed using SPSS V.24 (International Business Machines, Armonk, New York). Data were summarised using descriptive statistics, including counts and percentages for categorical data and median and range for non-normally distributed data. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality of data. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess multiple non-parametric groups. Comparison between categorical data between both groups was performed using χ2 testing. Statistical significance was considered when p<0.05.

Results

Hospitals within all NHS trusts were contacted (n=209). There were 51 trusts which did not provide any GI dietetic services (these were mental health trusts, ambulance trusts, community health trusts, social care trusts, specialist trusts (eg, heart and chest, women’s health, eye, cancer, neonatology, orthopaedic)). Surveys were completed from 123 out of 158 trusts (78%) with GI dietetic services. The majority of hospitals which responded were from district general hospitals (51%), followed by central teaching hospitals (28%) and the community (21%). The completion rate by region is shown in table 1, with no statistically significant difference in response rate by region (p=0.12).

Table 1.

Responses to dietetic survey by region

| Region | Number of trusts with GI dietetic services | Number of trust responses | Percentage of trusts responded (%) |

| East of England | 19 | 11 | 58 |

| North East and Yorkshire | 24 | 19 | 79 |

| London | 24 | 19 | 79 |

| Midlands | 24 | 18 | 75 |

| North West | 23 | 22 | 96 |

| South East | 24 | 17 | 71 |

| South West | 20 | 17 | 85 |

| Total | 158 | 123 | 78 |

GI, gastrointestinal.

The full-time equivalent (FTE) dietitians per head of populations was 3.64/100 000 (range 0.15–16.60) across England. There was a statistically significant difference (p=0.03) between regions, with the highest being noted in North East and Yorkshire (5.86 FTE/100 000 (range 0.20–9.19)) and lowest being noted in North West region (2.16 FTE/100 000 (range 0.36–14.00)), as seen in table 2.

Table 2.

Full-time equivalent (FTE) dietitians by region

| Region | FTE dietitians/100 000 |

| East of England | 2.38 (0.48–16.60) |

| North East and Yorkshire | 5.86 (0.20–9.19) |

| London | 3.25 (1.06–14.40) |

| Midlands | 3.68 (0.15–8.50) |

| North West | 2.16 (0.36–14.00) |

| South East | 4.09 (0.92–8.33) |

| South West | 3.40 (0.70–8.33) |

| Total | 3.64 (0.15–16.60) |

Across England, the vast majority of trusts provided a general dietetic service for adults with CD (95%, n=117), IBS (96%, n=118) and IBD (94%, n=116). Sixty-three per cent (n=78) of trusts provided a general dietetic service for children with CD and 50% (n=61) provided a general dietetic service for children with IBD.

Hours allocated monthly varied between conditions (p<0.01), with median hours allocated to IBS being the highest at 15 (range 0–175) hours/month, whereas median time allocated to CD was 6 (range 0–40) hours/month and IBD was 7 (range 0–100) hours/month.

The most frequent waiting time for individuals to be seen was <2 months for individuals with CD and IBD, whereas it was longer for IBS at 2–4 months. In terms of consultation length, the most frequent consultation length was 15–30 min for patients with IBS, CD and IBD (table 3).

Table 3.

Provision of dietetic services for coeliac disease (CD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

| CD | IBS | IBD | |

| n (%)* | n (%)* | n (%)* | |

| Band of dietitian with main responsibility of service† | |||

| 5 | 6 (8) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) |

| 6 | 40 (53) | 41 (61) | 44 (56) |

| 7 | 28 (37) | 22 (33) | 33 (42) |

| 8 or above | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Specialist clinic frequency | |||

| Weekly | 21 (33) | 27 (44) | 18 (51) |

| Fortnightly | 13 (21) | 10 (16) | 6 (17) |

| Monthly | 20 (32) | 24 (39) | 10 (29) |

| Less than monthly | 9 (14) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) |

| Policy for management of condition | |||

| Yes | 58 (47) | 66 (54) | 30 (24) |

| No | 65 (53) | 57 (46) | 93 (76) |

| Waiting time | |||

| <2 months | 84 (72) | 46 (39) | 65 (57) |

| 2–4 months | 32 (27) | 58 (50) | 42 (37) |

| 4–6 months | 0 (0) | 11 (9) | 7 (6) |

| >6 months | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Consultation length | |||

| <15 min | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 15–30 min | 51 (43) | 51 (44) | 64 (54) |

| 30–45 min | 48 (41) | 49 (42) | 44 (37) |

| 45–60 min | 16 (14) | 16 (14) | 10 (9) |

| Teaching method used‡ | |||

| Individual | 116 (94) | 115 (94) | 117 (95) |

| Group | 39 (32) | 42 (34) | 1 (1) |

*n denotes number of trusts.

†Note that band refers to pay band for majority of National Health Service workers, on scale of 1–9, with 9 being the highest.

‡Note that some trusts offered both individual and group clinics.

Approximately half of all trusts had a dietitian responsible for the delivery of CD (54% n=66), IBS (49%, n=60) and IBD (59%, n=72) services. The majority of individuals with the main responsibility of delivering this service were band 6 dietitians (pay band, scaled from 1 to 9) for all GI services (table 3).

Out of those trusts who had a dietitian responsible for GI dietetic service delivery, 52% (n=34) had received post registration training in CD, 92% (n=55) had received post registration training in IBS and 57% (n=41) had received post registration training in IBD. The most common professional membership for these individuals was the BDA (97% (n=64) for CD, 98% (n=65) for IBS and 96% (n=69) for IBD) and Coeliac UK (82% (n=54) for CD, 58% (n=35) for IBS and 40% (n=29) for IBD).

Specialist clinics were defined as dietetic clinics designated for the management of one condition, rather than general dietetic clinics where patients with a wide variety of conditions were seen. A large proportion of trusts did not deliver any specialist clinics for CD, IBS and IBD (49% (n=60), 50% (n=61) and 72% (n=88), respectively). Out of those who had specialist clinics, the frequency of clinics is outlined in table 3, with weekly clinics being the most frequent.

Forty-seven per cent of trusts had policies for the dietetic management of CD, 54% of trusts had policies for the dietetic management of IBS, whereas only 24% had policies for the dietetic management of IBD.

The large majority of trusts delivered teaching on dietetic therapies on a one-to-one basis (table 3). A large number of trusts also delivered teaching through group therapies, particularly for CD (32%, n=39) and IBS (34%, n=42) rather than IBD (1%, n=1).

Discussion

This is the first study since 2007 assessing the provision of gastroenterology dietetic services in England, and the first to assess the provision of IBS and IBD services in addition to CD. This study had a high response rate (78%), which compares favourably to the previous study looking at the provision of dietetic services in CD, which had a response rate of 38%.2 There was no statistically significant difference in response rates between regions, with these findings likely to be an accurate representation of the provision of services across England.

There was a significant difference in the number of FTE dietitians per population by region, highlighting the variation in dietetic GI service delivery across England, similar to the previous study assessing the provision of CD in the UK.2 This may in part be due to variation in funding of GI dietetic services across England, although funding was not assessed.

While the vast majority of trusts provided a general dietetic service for CD, IBS and IBD, it appears that a large proportion of trusts do not have specialist dietetic gastroenterology services. Adherence to dietary therapies has been demonstrated to be improved by patients having regular access and follow-up in clinic.7 This highlights that individuals requiring dietary therapies are failing to receive specialist advice, despite this being advocated in the literature.4 8 9 CD is common, with a prevalence of 1%, with diet being the mainstay of treatment. Without access to specialist services, these individuals are likely to be at an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies, such as deficiencies of folate, calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc and fibre intake.10–12 In addition to this, most dietary interventions have been demonstrated to be clinically effective via the delivery from a dietitian.4 Dietetic interventions can also be challenging with dietitians being well placed to address patient well-being and psychological distress.13

The prevalence of IBS is also high, reported at approximately 10%, with diet being reported as a trigger in up to 84% of patients.14–17 Dietary therapies for IBS can be complex to implement such as the low FODMAP diet, with specialist dietetic input being essential in the implementation of these diets.8 In view of this, it is likely that many patients with IBS are not receiving dietary interventions or are self-implementing these diets. A large study of 1500 gastroenterologists demonstrated that a common mode to provide nutritional advice to patients with IBS by gastroenterologists was educational handouts (81%), highlighting the suboptimal care patients are currently receiving.18

A greater proportion of individuals are receiving post registration training in IBS versus CD and IBD. This may in part maybe due to an increase in knowledge of the role of dietary therapies in IBS, as well as the emerging evidence for the role of dietitians in the delivery of these dietary therapies.5 8 It is also worth noting that dietetic training for IBS in England is commonly delivered through paid courses, and arguably this should be embedded within their teaching curriculum in view of the high prevalence of IBS.

There seems to be disparity between recommended consultation time in the literature and true clinical practice. In the literature, it is recommended that 45–60 min is required for a new patient to educate them on a low FODMAP diet,19 whereas the most frequent consultation length was 15–30 min in this study. This highlights the challenges to dietetic services to deliver these therapies effectively. The most common mode of dietetic review was on a one-to-one basis. Of note, there were an increasing number of individuals who were seen in group clinics, mainly for CD and IBS. There appears to be an emerging role for the use of group clinics within and outside the field of gastroenterology, with group clinics being a potential way to increase efficacy of seeing patients.20–24 This method could potentially bridge capacity issues in delivering these dietetic therapies effectively, although further studies are required.

A large proportion of trusts did not have policies for the dietetic management of either CD, IBS or IBD. This suggests that the delivery of care within trusts maybe heterogenous, although it is worth noting that national guidelines are available such as National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and BDA guidelines.5 25

There are potential limitations with this study. First, this study assessed the provision of GI services in England only. While this study is likely to be representative of the provision of dietetic services across England, this may not be representative of the entire NHS which encompasses the UK. Also, as this is the first study assessing the dietetic provision of CD, IBS and IBD together, there are little data outlining previous provision to compare. Also, there is little guidance on the required level of GI dietetic services to deliver an effective service in England.

To conclude, there appears to be an inequity of GI dietetic services across England, with regional differences in the level of provision and the extent of specialist care. A large proportion of patients are failing to receive specialist dietetic care, likely leading to patients self-implementing or not implementing dietary interventions, despite evidence of their efficacy. National guidance is required to guide the level of GI dietetic services required to deliver an effective service.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Coeliac UK and British Dietetic Association for raising the awareness of this dietetic survey.

Footnotes

Contributors: AR and DSS developed the study. AR, RLB, CCS and NT collected the data. AR analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: DSS receives an educational grant from Schaer (a gluten‐free food manufacturer). Dr Schaer did not have any input in drafting of this manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Hickson M, Child J, Collinson A. Future dietitian 2025: Informing the development of a workforce strategy for dietetics. J Hum Nutr Diet 2018;31:23–32. 10.1111/jhn.12509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nelson M, Mendoza N, McGough N. A survey of provision of dietetic services for coeliac disease in the UK. J Hum Nutr Diet 2007;20:403–11. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00813.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2018;391:70–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rej A, Avery A, Ford AC, et al. Clinical application of dietary therapies in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2018;27:307–16. 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.273.avy [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McKenzie YA, Bowyer RK, Leach H, et al. British dietetic association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J Hum Nutr Diet 2016;29:549–75. 10.1111/jhn.12385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forbes A, Escher J, Hébuterne X, et al. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr 2017;36:321–47. 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bardella MT, Molteni N, Prampolini L, et al. Need for follow up in coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child 1994;70:211–3. 10.1136/adc.70.3.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Keeffe M, Lomer MC. Who should deliver the low FODMAP diet and what educational methods are optimal: a review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;32:23–6. 10.1111/jgh.13690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rej A, Sanders DS. Gluten-Free Diet and Its 'Cousins' in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nutrients 2018;10. 10.3390/nu10111727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wild D, Robins GG, Burley VJ, et al. Evidence of high sugar intake, and low fibre and mineral intake, in the gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:573–81. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04386.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson T, Dennis M, Higgins LA, et al. Gluten-Free diet survey: are Americans with coeliac disease consuming recommended amounts of fibre, iron, calcium and grain foods? J Hum Nutr Diet 2005;18:163–9. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00607.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Nutritional inadequacies of the gluten-free diet in both recently-diagnosed and long-term patients with coeliac disease. J Hum Nutr Diet 2013;26:349–58. 10.1111/jhn.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barratt SM, Leeds JS, Sanders DS. Quality of life in coeliac disease is determined by perceived degree of difficulty adhering to a gluten-free diet, not the level of dietary adherence ultimately achieved. J Gastrointest Liver Dis 2011;20:241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:712–21. 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, et al. Food-Related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 2001;63:108–15. 10.1159/000051878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Monsbakken KW, Vandvik PO, Farup PG. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome-- etiology, prevalence and consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006;60:667–72. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, et al. Self-Reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:634–41. 10.1038/ajg.2013.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lenhart A, Ferch C, Shaw M, et al. Use of dietary management in irritable bowel syndrome: results of a survey of over 1500 United States Gastroenterologists. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;24:437–51. 10.5056/jnm17116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whelan K, Martin LD, Staudacher HM, et al. The low FODMAP diet in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: an evidence-based review of FODMAP restriction, reintroduction and personalisation in clinical practice. J Hum Nutr Diet 2018;31:239–55. 10.1111/jhn.12530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whigham L, Joyce T, Harper G, et al. Clinical effectiveness and economic costs of group versus one-to-one education for short-chain fermentable carbohydrate restriction (low FODMAP diet) in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet 2015;28:687–96. 10.1111/jhn.12318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fisher EB, Boothroyd RI, Coufal MM, et al. Peer support for self-management of diabetes improved outcomes in international settings. Health Aff 2012;31:130–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krishnamoorthy Y, Sakthivel M, Sarveswaran G, et al. Effectiveness of peer led intervention in improvement of clinical outcomes among diabetes mellitus and hypertension patients-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes 2019;13:158–69. 10.1016/j.pcd.2018.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steinsbekk A, Rygg Lisbeth Ø, Lisulo M, et al. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:213. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rej A, Trott N, Kurien M, et al. Is peer support in group clinics as effective as traditional individual appointments? the first study in patients with celiac disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2020;11:e00121. 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management. Clinical Guideline [CG61], 2017. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.