Abstract

Background and Purpose

We explored whether high-degree MRI-visible perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale are more prevalent in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) than hypertensive small vessel disease (SVD) and their relationship to brain amyloid retention in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

Methods

One-hundred and eight spontaneous ICH patients who underwent MRI and PiB were enrolled. Topography and severity of enlarged perivascular spaces were compared between CAA-related ICH (CAA-ICH) and hypertensive SVD related ICH (non-CAA ICH). Clinical and image characteristics associated with high-degree perivascular spaces were evaluated in univariate and multivariable analyses. Univariate and multivariable models were performed to evaluate associations between the severity of perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale and amyloid retention in CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH cases.

Results

Patients with CAA-ICH (n=29) and non-CAA ICH (n=79) had similar prevalence of high-degree perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale (44.8% vs. 36.7%, p=0.507) and in basal ganglia (34.5% vs. 51.9%, p=0.131). High-degree perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale were independently associated with the presence of lobar microbleed (OR=3.0, 95% CI 1.1–8.0, p=0.032). The amyloid retention was higher in those with high-degree than those with low-degree centrum semiovale-perivascular spaces in CAA-ICH (Global PiB standardized uptake value ratio 1.55 [1.33–1.61] vs 1.13 [1.01–1.48], p=0.003), but not in non-CAA ICH. In CAA-ICH, the association between cerebral amyloid retention and the degree of perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale remained significant after adjustment for age and lobar microbleed number (p=0.004).

Conclusions

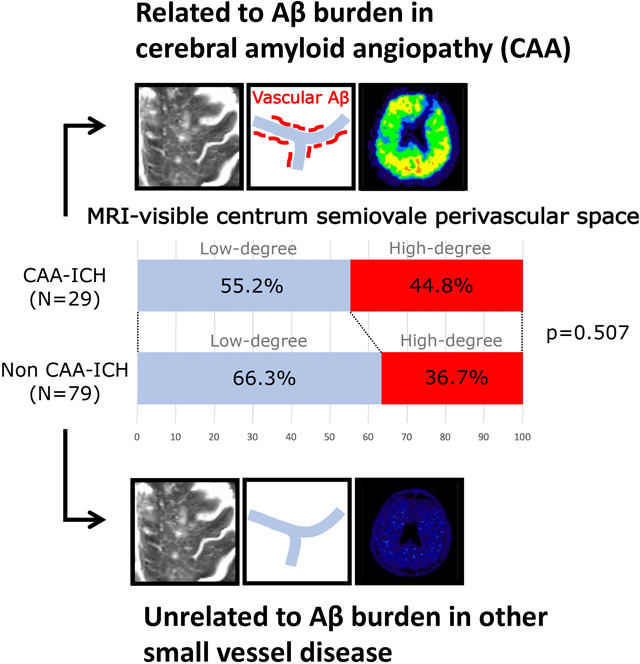

Although high-degree MRI-visible perivascular spaces is equally prevalent between CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH in Asian cohort, the severity of MRI-visible centrum semiovale-perivascular spaces may be an indicator of higher brain amyloid deposition in patients with CAA-ICH.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Small vessel diseases (SVDs), including sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and hypertensive SVD (i.e., arteriolosclerosis), are the most common etiologies in primary intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).1 In addition to the topography of hematoma and cerebral microbleed (CMB), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-visible enlarged perivascular spaces have recently been suggested as another indicator for underlying SVD type. A higher load of enlarged perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale (CSO) is found in CAA, while severe perivascular spaces in the basal ganglia (BG) are more prevalent in hypertensive SVD.2 It is hypothesized that MRI-visible perivascular spaces in CAA may be an indicator of chronic poor perivascular drainage of the leptomeningeal arteries, which predisposes individuals to defective amyloid clearance and CAA development.3, 4

The relationship between amyloid deposition and the topography of enlarged perivascular spaces in primary ICH patients has never been investigated in Asians, a population who tend to have a high overall rate of hypertensive SVD.5, 6 In the present study, we assess whether severe CSO-perivascular spaces are more prevalent in CAA-related ICH (CAA-ICH) than non-CAA ICH cases in an Asian population, and whether they are associated with other MRI signatures related to CAA. Furthermore, we evaluate the association between the severity of CSO-perivascular spaces and brain amyloid deposition separately in patients with CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH.

METHODS

Data availability.

Any data not published within the article are available by request within the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). Such datasets will be shared on request from a qualified investigator.

Patient enrollment.

We prospectively recruited patients aged 20 years or older with symptomatic primary ICH who were treated at NTUH between September 2014 and January 2020.7, 8 We excluded patients with potential causes of secondary hemorrhage, including trauma, structural and vascular lesions, brain tumor, severe coagulopathy due to systemic disease or medication, or those who had ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic transformation. Patients were excluded if they could not tolerate imaging studies, including those with poor cooperation, hemodynamic instability, and implantation of cardiac pacemaker. Those who had a history of dementia (clinical dementia rating ≥1) were also excluded.

A total of 115 patients who fulfilled the enrollment criteria agreed to participate in this study (Figure 1). These patients underwent brain MRI and 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Patients with lobar ICHs involving the cerebral cortex and underlying white matter with or without strictly lobar CMBs or cortical superficial siderosis (cSS) were defined as possible (n=6) or probable CAA-ICH (n=23) according to modified Boston criteria.9 Patients were defined as non-CAA ICH (n=86) if the ICH and CMBs were exclusively located in the basal ganglia (BG), thalamus, or infratentorial region (deep locations) or if there was a combination of mixed lobar and deep bleeds. Non-CAA ICH patients with positive cSS (n=7) were excluded from the analysis for potential underlying CAA.8

Figure 1:

Flowchart of patient enrollment.

Baseline clinical data were collected through a comprehensive review of medical records as previously described.7, 8 The following clinical variables were systemically recorded for each subject: age, sex, presence of hypertension (defined as clinical diagnosis of hypertension with more than 3 months of prescription of anti-hypertensive agents), classes of anti-hypertensive medication, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, history of ICH and ischemic stroke, and values of creatinine clearance (represented by estimated glomerular filtration rate).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was performed with the approval of the institutional review board (201404065MIND) of NTUH and in accordance with their guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their family members.

MRI acquisition and analysis.

Brain MRIs were obtained using a 3-tesla scanner (Siemens Verio, TIM, or mMR; Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA). The imaging protocols included T1-weighted imaging, T2- weighted imaging, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging, susceptibility weighted imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging, and apparent diffusion coefficient maps. MRI-visible perivascular spaces were evaluated on T2-weighted imaging and were defined as sharply delineated structures measuring <3 mm following the course of perforating or medullary vessels.2 The number of MRI-visible perivascular spaces was counted in CSO and BG on the side of the brain with more severe involvement. The severity of enlarged perivascular spaces was rated with a validated 4-point visual scale (0 = none, 1 = <10, 2 = 11–20, 3 = 21–40, and 4 = >40).2, 10 According to a previous proposed method, we pre-specified a dichotomized classification of high (scale 3 and 4) or low (scale 0 to 2).2 The perivascular spaces visual scale was independently evaluated by two authors (H.H. Tsai and B.C. Lee), and a consensus was achieved after discussion if there was disagreement.

For the other MRI markers, the presence and location of supratentorial CMBs were evaluated as previously described.11 CMBs are defined as lesions with homogeneous round signal loss (less than 10 mm in diameter) on SWI but not as symmetric hypointensities and flow voids from blood vessels. CMBs were counted in the lobar region and deep region using the Microbleed Anatomical Rating Scale.12 Lacunes were evaluated in the supratentorial region and defined as “round or ovoid, subcortical, fluid-filled cavity, between 3 mm and 15mm in diameter” according to the Standards for Reporting Vascular Changes on Neuroimaging criteria.13, 14 WMH volume was calculated based on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging using a semi-automated measure, as previously described.8, 15 The volume estimates were performed in the ICH-free hemisphere and multiplied by two.

PET acquisition and analysis.

11C-PiB was manufactured and handled according to good manufacturing practices at the PET center, NTUH, Taipei, Taiwan (specificity activity: 39 ± 19 GBq/μmol [n = 144]). PET scanning was performed within 3 months after the MRI acquisition. Static PET/CT scans (Discovery ST; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) were acquired in 3-dimensional mode for 30 minutes starting at 40 minutes after the injection of 10 mCi 11C-PiB. PET data were reconstructed with ordered set expectation maximization (5 iterations, 32 subsets, post filter 2.57) and were corrected for attenuation. Each PiB PET image was realigned, resliced, and manually co-registered to a standardized CT template using PMOD software as previously described.8, 15

The PET data were semi-quantitatively analyzed and expressed as the average mean standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) of the regions of interest using the cerebellar cortex as a reference region.7 The regions of interest in these spatially normalized images included the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes based on the Automated Anatomical Labeling atlas. Areas of macrobleeds were manually excluded for SUVR analyses, and the parameter in this specific region of interest was calculated using the ICH-free hemisphere.

Statistical analysis.

We compared the prevalence of high-degree CSO- and BG-perivascular spaces between the CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH groups. We also compared the baseline demographic information and neuroimaging variables between groups with high-degree and low-degree perivascular spaces in a univariable analysis, and the results are presented in table 1 and table 2. Discrete variables are presented as the count (%), and continuous variables are presented as the mean (±standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), as appropriate based on their distribution. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed using an independent-samples t test (for normal distributions) and Mann-Whitney U test (for non-normal distributions). A multivariable logistic regression model was built to examine the independent association between high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces and relevant demographic information (age, presence/absence of chronic hypertension), and neuroimaging variables with a p-value <0.1 in the univariable analysis (presence/absence of lobar CMB, WMH volume, and presence/absence of cSS). A similar logistic regression model was also built to investigate the independent associations between high-degree BG-perivascular spaces, relevant demographic information (age, presence/absence of chronic hypertension), and neuroimaging variables with a p-value <0.1 in the univariable analysis (presence/absence of lobar CMB, deep CMB, WMH volume).

Table 1.

Comparison of patients with high- and low-degree MRI-visible perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale.

| High-degree CSO-perivascular spaces (n=42) | Low-degree CSO-perivascular spaces (n=66) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % | 14 (33.3%) | 23 (34.8%) | 1.000 |

| Age, y | 67.2 ±11.4 | 62.5 ± 12.7 | 0.054 |

| Hypertension | 35 (83.3%) | 54 (81.8%) | 0.802 |

| CAA-ICH | 13 (31.0%) | 16 (24.2%) | 0.507 |

| Cerebral microbleed | |||

| Presence of lobar CMB | 35 (83.3%) | 38 (57.6%) | 0.006 |

| Presence of deep CMB | 25 (59.5%) | 34 (51.5%) | 0.435 |

| WMH volume, mL (IQR) | 18.2 (7.9–29.3) | 10.6 (2.8–24.3) | 0.039 |

| Lacunes, % | 27 (64.3%) | 32 (48.5%) | 0.384 |

| Cortical superficial siderosis, % | 6 (14.3%) | 2 (6.3%) | 0.054 |

Values are mean (±standard deviation), median (IQR) or number (percentage). CAA: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CMB: cerebral microbleeds; IQR: interquartile range; WMH: white matter hyperintensities

Table 2.

Comparison of patients with high- and low-degree MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia.

| High-degree BG-perivascular spaces (n=51) | Low-degree BG-perivascular spaces (n=57) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % | 14 (27.4%) | 23 (40.4%) | 0.223 |

| Age, y | 66.5 ± 9.8 | 62.4 ± 14.2 | 0.080 |

| Hypertension | 43 (84.3%) | 45 (78.9%) | 0.621 |

| CAA-ICH | 10 (19.6%) | 19 (33.3%) | 0.131 |

| Cerebral microbleed | |||

| Presence of lobar CMB | 40 (78.4%) | 33 (57.9%) | 0.025 |

| Presence of deep CMB | 36 (67.9%) | 23 (40.4%) | 0.002 |

| WMH volume, mL | 19.5 (7.9–32.2) | 9.1 (2.9–20.8) | 0.005 |

| Presence of lacune, % | 32 (62.7) | 27 (47.4%) | 0.125 |

| Cortical superficial siderosis, % | 3 (5.9%) | 5 (8.8%) | 0.720 |

Values are mean (±standard deviation), median (IQR) or number (percentage). CAA: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CMB: cerebral microbleeds; IQR: interquartile range; WMH: white matter hyperintensities

For PET imaging analyses, global, frontal, and occipital SUVRs were compared in univariate analyses between high-degree and low-degree perivascular spaces in CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH, respectively. In the multivariable linear regression model, PiB SUVR was used as a dependent variable to look for independent associations between the degree of CSO-perivascular spaces after adjustment for age and lobar CMB number. The kappa statistic was calculated to evaluate the inter-observer reliability for the grading of MRI-visible perivascular spaces. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All tests of significance were 2-tailed with a threshold for significance of p< 0.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-nine CAA-ICH cases (mean age 72.4 ± 12.0 years) and 79 non-CAA ICH cases (mean age 61.3 ± 11.2 years) were included in the analyses (supplementary table). The global amyloid burden was significantly higher in the CAA-ICH group than the non-CAA ICH group (PiB global SUVR 1.40 [1.06–1.56] vs. 1.08 [1.01–1.21], p<0.001). The interrater agreement for detecting high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces and BG-perivascular spaces was very good (k=0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.50–0.98; k=0.80, 95% CI 0.59–1, respectively). CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH patients had similar prevalence of high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces (44.8% vs. 36.7%, p=0.507) and high-degree BG-perivascular spaces (34.5% vs. 51.9%, p=0.131).

Table 1 and table 2 show univariable comparisons of the characteristics between patients with high-degree and low-degree perivascular spaces. Patients with high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces showed a higher prevalence of lobar CMB (p=0.006), higher WMH volumes (p=0.039), and a trend toward older age (p=0.054) and higher prevalence of cSS (p=0.054) (table 1). In the multivariable analyses, high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces remained significantly associated with the presence of lobar CMB (OR=3.0, 95% CI 1.1–8.0, p=0.032) after adjustment for age, hypertension, WMH volume, and cSS. On the other hand, patients with high-degree BG-perivascular spaces showed more prevalent lobar CMB (p=0.025) and deep CMB (p=0.001), and were associated with higher WMH volume (p=0.005) (table 2). In multivariable analyses, high-degree BG-perivascular spaces were significantly associated with age (OR=1.04, 95% 1.00–1.08, p=0.049) and the presence of deep CMB (OR=4.2, 95% CI 1.7–10.5, p=0.002) after adjustment for the presence/absence of hypertension, presence/absence of lobar CMB, and WMH volume.

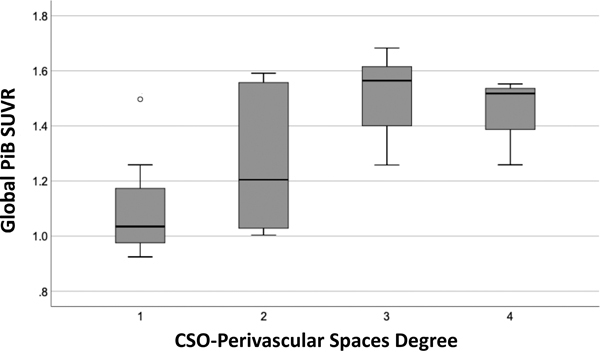

Table 3 shows the global and regional (frontal, occipital lobes) amyloid retention (SUVR) in the CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH groups. The global and regional amyloid retention was higher in those with high-degree than those with low-degree CSO-perivascular spaces in CAA-ICH cases (all p<0.05), but not in non-CAA ICH case (all p>0.05). The global amyloid load in the CAA-ICH group across different degrees of CSO-perivascular spaces is shown in figure 2. In the multivariable analysis, the degree of CSO-perivascular spaces remained independently associated with higher global (β=0.47, p=0.004) or regional SUVR (frontal SUVR: β=0.44, p=0.012; occipital SUVR: β=0.53, p=0.002) after adjustment for age and lobar CMB number in CAA-ICH patients.

Table 3.

Amyloid deposition (SUVR) in high- vs low-degree perivascular spaces.

| Global SUVR | P value | Frontal SUVR | P value | Occipital SUVR | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAA-ICH (n=29) | ||||||

| High-degree CSO-perivascular spaces (n=13) | 1.55 (1.33–1.61) | 0.003* | 1.54 (1.33–1.62) | 0.002* | 1.53 (1.42–1.60) | 0.001* |

| Low-degree CSO-perivascular spaces (n=16) | 1.13 (1.01–1.48) | 0.003* | 1.13 (1.00–1.44) | 0.002* | 1.13 (1.06–1.31) | 0.001* |

| High-degree BG-perivascular spaces (n=10) | 1.38 (1.02–1.55) | 0.521 | 1.36 (1.03–1.58) | 0.927 | 1.37 (1.07–1.53) | 0.680 |

| Low-degree BG-perivascular spaces (n=19) | 1.40 (1.09–1.59) | 0.521 | 1.34 (1.08–1.54) | 0.927 | 1.35 (1.12–1.58) | 0.680 |

| Non-CAA ICH (n=79) | ||||||

| High-degree CSO-perivascular spaces (n=29) | 1.06 (1.00–1.13) | 0.515 | 1.00 (0.94–1.10) | 0.183 | 1.14 (1.05–1.19) | 0.535 |

| Low-degree CSO-perivascular spaces (n=50) | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 0.515 | 1.04 (0.98–1.14) | 0.183 | 1.12 (1.03–1.17) | 0.535 |

| High-degree BG-perivascular spaces (n=41) | 1.06 (1.00–1.13) | 0.768 | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 0.791 | 1.12 (1.04–1.16) | 0.666 |

| Low-degree BG-perivascular spaces (n=38) | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 0.768 | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | 0.791 | 1.13 (1.04–1.21) | 0.666 |

Values are median (interquartile range). BG: basal ganglia; CAA: cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CSO: centrum semiovale; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; and SUVR, standardlized uptake value ratio.

p<0.05.

Figure 2:

The global amyloid retention in cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related intracerebral hemorrhage.

Boxplot showing the median values and interquartile ranges of the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) in CAA-ICH patients across degrees of MRI-visible enlarged perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that the prevalence of high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces and high-degree BG-perivascular spaces is similar between CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH groups in an Asian population with primary ICH. High-degree CSO-perivascular spaces were associated with the presence of lobar CMB, while high-degree BG-perivascular spaces were associated with the presence of deep CMB. Furthermore, CAA patients with high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces had higher cortical PiB retention than patients with low-degree, and this result remained significant after adjustment for age and lobar CMB. Our findings suggest that MRI-visible enlarged perivascular spaces in CSO are associated with vascular amyloid deposition in only CAA-ICH patients, while they are probably related to a process other than CAA in hypertensive SVD.

Perivascular spaces are interstitial fluid-filled spaces around small perforating arteries as they course from the brain surface into and through the brain parenchyma.13 Normal perivascular spaces are not typically seen in conventional structural MRI, and can only be visualized when they are enlarged. MRI-visible perivascular spaces have recently been viewed as a feature of SVD.16 They are defined as fluid-filled spaces that follow the typical course of a vessel as it goes through grey or white matter, and have signal intensity similar to that of CSF in all sequences.13 Previous observational studies have shown that the severity of perivascular spaces in BG was associated with hypertension and MRI SVD markers of chronic hypertension, such as WMH and lacunar infarction.17 In contrast, enlarged perivascular spaces in CSO were more consistently associated with age and was considered to have different pathophysiology.10, 18 In a Caucasian cohort of spontaneous ICH cases, severe CSO-perivascular spaces was also associated with CAA-related MRI markers, such as lobar CMB and cSS.2 Another study investigating the volume of perivascular spaces also found a higher volume of perivascular spaces in pathological confirmed CAA patients than non-CAA patients.19 In line with previous findings, our study showed that a high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces is independently associated with lobar CMB and that high-degree BG-perivascular spaces is independently associated with deep CMB. However, the prevalence of severe perivascular spaces in CSO and BG was similar between the CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH groups. This result might be explained by the overall higher burden of SVD caused by chronic hypertension in this Asian cohort than Caucasian cohorts, as suggested by previous findings.20 The inclusion of mixed lobar and deep hemorrhages in our study, with possible extension of their severe small vessel disease into the lobar area, may also be the main cause of higher number of CSO perivascular spaces in the non-CAA ICH group. However, excluding patients with mixed location hemorrhages did not significantly change the prevalence of severe CSO-perivascular spaces in our cohort. Therefore, perivascular spaces topography in distinguishing the dominant types of SVD should be used more cautiously in Asian primary ICH patients.

It is hypothesized that enlarged perivascular spaces in CAA are an indicator of chronic poor perivascular drainage of the leptomeningeal arteries, which predisposes individuals to defective amyloid clearance and CAA development.3, 4 The strength of the current study is the use of PiB PET to investigate the correlation between the severity of CSO-perivascular spaces and cerebrovascular amyloid deposition. Previously, a pilot study showed that there is an association between whole-cortex PiB retention and the degree of CSO-perivascular spaces across the spectrum of CAA in a combined group of probable CAA-related ICH and healthy elderly subjects.21 On the other hand, another study on Alzheimer’s disease revealed no correlation between the severity of CSO-perivascular spaces and amyloid burden.22 We also confirmed that a higher load of CSO-perivascular spaces in patients with CAA-ICH was independently associated with higher PiB retention also in Asian population. Our results provide evidence that CSO-perivascular spaces might be associated with cerebrovascular amyloid deposition in spontaneous ICH patients in relation to underlying CAA pathology. However, this association was not found in the non-CAA ICH group, suggesting that high-degree CSO-perivascular spaces may be related to other processes other than CAA in hypertensive SVD. Previous studies suggest that hypertensive SVD could involve not only deep areas but also lobar areas,8, 23 which could also possibly contribute to the severe CSO-perivascular spaces in the absence of CAA.

One of the major limitations in this study was the classification of ICH etiology (CAA-ICH vs non-CAA ICH) based on MRI macrobleed/microbleed distribution instead of pathological evidence. We included mixed-location ICH patients in which the underlying microangiopathy is considered mostly hypertensive SVD.8, 23 However, we excluded non-CAA ICH patients with positive cSS to minimize coexisting CAA in these patients.8 On the other hand, 6 CAA-ICH patients presented with single lobar ICH without any CMB or cSS (possible CAA per the Boston Criteria), and their hemorrhage might also be a consequence of hypertensive SVD. However, repeating the analyses while excluding possible CAA from the analyses did not change our results. Second, cerebral amyloid deposition can be attributed to Alzheimer’ disease, CAA, or normal aging. Previous reports have shown that amyloid PET has good diagnostic utility in an appropriate clinical setting,24 although parenchymal instead of vascular amyloid deposition cannot be completely excluded in our patients with high PiB binding. In order to minimize the confounding effect of Alzheimer’s pathology, only patients without overt dementia (clinical dementia rating < 1) were included in the PiB PET study. Finally, the sample size in this study was relatively small, and our cross-sectional design could not prove a causality between CAA and CSO-perivascular spaces in CAA-ICH patients. Larger MRI/PET studies with longitudinal data are necessary to validate the present results.

In conclusion, high-degree perivascular spaces in CSO were equally prevalent between CAA-ICH and non-CAA ICH cases in an Asian cohort. CSO-perivascular spaces are independently related to the presence of lobar CMB, but the degree of CSO-perivascular spaces is associated with higher amyloid load in only CAA-ICH patients. Our results expand the hypothesis that a higher burden of CSO-perivascular spaces can be regarded as an indicator of more severe vascular amyloid deposition in patients with CAA, but it is probably related to another process in patients with hypertensive SVD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

We thank the staff of the Second Core Lab, Department of Medical Research, National Taiwan University Hospital for technical support during the study.

Sources of funding: This work was supported by grants from Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (Tsai HH, MOST 109-2628-B-002-025) and National Institutes of Health (Gurol ME, NINDS/NIA R01NS11452, NS 083711, 5R01NS096730–04, 5R01AG026484).

Financial disclosures:

Dr Li-Kai Tsai reports grants and personal fees from Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology, grants from Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, personal fees from Boehringer-ingelheim, grants from Biogen, personal fees from Pfizer, and personal fees from Daiiki-Sankyo outside the submitted work.

Dr. Edip Gurol reports research support from AVID (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly), Boston Scientific Corporation, and Pfizer outside the submitted work.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- BG

Basal ganglion

- CAA

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CMB

Cerebral microbleed

- CSO

Centrum semiovale

- cSS

Cortical superficial siderosis

- ICH

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SVD

Small vessel disease

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PiB

Pittsburgh compound B

- WMH

White matter hyperintensity

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Supplementary materials: Supplementary table

REFERENCES

- 1.Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, Batjer HH, Hondo H, Hanley DF. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344:1450–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Pasi M, Auriel E, van Etten ES, Haley K, Ayres A, Schwab KM, Martinez-Ramirez S, Goldstein JN, et al. Mri-visible perivascular spaces in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive arteriopathy. Neurology. 2017;88:1157–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkes CA, Jayakody N, Johnston DA, Bechmann I, Carare RO. Failure of perivascular drainage of beta-amyloid in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Pathol. 2014;24:396–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkes CA, Hartig W, Kacza J, Schliebs R, Weller RO, Nicoll JA, Carare RO. Perivascular drainage of solutes is impaired in the ageing mouse brain and in the presence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:431–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mok V, Srikanth V, Xiong Y, Phan TG, Moran C, Chu S, Zhao Q, Chu WW, Wong A, Hong Z, et al. Race-ethnicity and cerebral small vessel disease--comparison between chinese and white populations. Int J Stroke. 2014;9 Suppl A100:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yakushiji Y, Wilson D, Ambler G, Charidimou A, Beiser A, van Buchem MA, DeCarli C, Ding D, Gudnason V, Hara H, et al. Distribution of cerebral microbleeds in the east and west: Individual participant meta-analysis. Neurology. 2019;92:e1086–e1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai HH, Tsai LK, Chen YF, Tang SC, Lee BC, Yen RF, Jeng JS. Correlation of cerebral microbleed distribution to amyloid burden in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai HH, Pasi M, Tsai LK, Chen YF, Lee BC, Tang SC, Fotiadis P, Huang CY, Yen RF, Jeng JS, et al. Microangiopathy underlying mixed-location intracerebral hemorrhages/microbleeds: A pib-pet study. Neurology. 2019;92:e774–e781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linn J, Halpin A, Demaerel P, Ruhland J, Giese AD, Dichgans M, van Buchem MA, Bruckmann H, Greenberg SM. Prevalence of superficial siderosis in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2010;74:1346–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doubal FN, MacLullich AM, Ferguson KJ, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Enlarged perivascular spaces on mri are a feature of cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke. 2010;41:450–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, Viswanathan A, Al-Shahi Salman R, Warach S, Launer LJ, Van Buchem MA, Breteler MM, Microbleed Study G. Cerebral microbleeds: A guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:165–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregoire SM, Chaudhary UJ, Brown MM, Yousry TA, Kallis C, Jager HR, Werring DJ. The microbleed anatomical rating scale (mars): Reliability of a tool to map brain microbleeds. Neurology. 2009;73:1759–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, Lindley RI, O’Brien JT, Barkhof F, Benavente OR, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasi M, Boulouis G, Fotiadis P, Auriel E, Charidimou A, Haley K, Ayres A, Schwab KM, Goldstein JN, Rosand J, et al. Distribution of lacunes in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive small vessel disease. Neurology. 2017;88:2162–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai HH, Pasi M, Tsai LK, Chen YF, Chen YW, Tang SC, Gurol ME, Yen RF, Jeng JS. Superficial cerebellar microbleeds and cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A magnetic resonance imaging/positron emission tomography study. Stroke. 2019:STROKEAHA119026235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardlaw JM, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, Zlokovic BV, Mestre H, Lee H, Doubal FN, Brown R, Ramirez J, MacIntosh BJ, et al. Perivascular spaces in the brain: Anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:137–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu YC, Tzourio C, Soumare A, Mazoyer B, Dufouil C, Chabriat H. Severity of dilated virchow-robin spaces is associated with age, blood pressure, and mri markers of small vessel disease: A population-based study. Stroke. 2010;41:2483–2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charidimou A, Meegahage R, Fox Z, Peeters A, Vandermeeren Y, Laloux P, Baron JC, Jager HR, Werring DJ. Enlarged perivascular spaces as a marker of underlying arteriopathy in intracerebral haemorrhage: A multicentre mri cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:624–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Ramirez S, van Rooden S, Charidimou A, van Opstal AM, Wermer M, Gurol ME, Terwindt G, van der Grond J, Greenberg SM, van Buchem M, et al. Perivascular spaces volume in sporadic and hereditary (dutch-type) cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2018;49:1913–1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai CF, Anderson N, Thomas B, Sudlow CL. Comparing risk factor profiles between intracerebral hemorrhage and ischemic stroke in chinese and white populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charidimou A, Hong YT, Jager HR, Fox Z, Aigbirhio FI, Fryer TD, Menon DK, Warburton EA, Werring DJ, Baron JC. White matter perivascular spaces on magnetic resonance imaging: Marker of cerebrovascular amyloid burden? Stroke. 2015;46:1707–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee G, Kim HJ, Fox Z, Jager HR, Wilson D, Charidimou A, Na HK, Na DL, Seo SW, Werring DJ. Mri-visible perivascular space location is associated with alzheimer’s disease independently of amyloid burden. Brain. 2017;140:1107–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasi M, Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Auriel E, Ayres A, Schwab KM, Goldstein JN, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Pantoni L, et al. Mixed-location cerebral hemorrhage/microbleeds: Underlying microangiopathy and recurrence risk. Neurology. 2018;90:e119–e126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charidimou A, Farid K, Baron JC. Amyloid-pet in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis. Neurology. 2017;89:1490–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Any data not published within the article are available by request within the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). Such datasets will be shared on request from a qualified investigator.