Keywords: autism, epilepsy, migraine, periodic paralysis, sodium channels

Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium channels initiate action potentials in nerve, skeletal muscle, and other electrically excitable cells. Mutations in them cause a wide range of diseases. These channelopathy mutations affect every aspect of sodium channel function, including voltage sensing, voltage-dependent activation, ion conductance, fast and slow inactivation, and both biosynthesis and assembly. Mutations that cause different forms of periodic paralysis in skeletal muscle were discovered first and have provided a template for understanding structure, function, and pathophysiology at the molecular level. More recent work has revealed multiple sodium channelopathies in the brain. Here we review the well-characterized genetics and pathophysiology of the periodic paralyses of skeletal muscle and then use this information as a foundation for advancing our understanding of mutations in the structurally homologous α-subunits of brain sodium channels that cause epilepsy, migraine, autism, and related comorbidities. We include studies based on molecular and structural biology, cell biology and physiology, pharmacology, and mouse genetics. Our review reveals unexpected connections among these different types of sodium channelopathies.

1. INTRODUCTION TO SODIUM CHANNELOPATHIES

Inherited sodium channelopathies are genetic diseases caused by mutations in sodium channels (1, 2), which are the primary focus of this review. In some diseases, alterations in sodium channel expression or function can occur through other means than genetic mutations. These acquired sodium channelopathies are of great interest, but they are not our focus here. The inherited periodic paralyses of skeletal muscle were the first recognized channelopathies (2, 3). They were mapped to the locus of the skeletal muscle sodium channel gene SCN4A that encodes the sodium channel NaV1.4, and both genetic and physiological studies confirmed a causal relationship between mutations in that gene and specific phenotypes of the periodic paralyses (2, 3). After these first studies, it was shown that mutations in the SCN1A gene encoding the brain sodium channel NaV1.1 cause genetic epilepsy (4), mutations in the SCN8A gene encoding the NaV1.6 channel cause paralysis in mice (4, 5), and mutations in the SCN9A gene encoding the NaV1.7 channel cause pain syndromes (6). Similarly, a large number of mutations in the SCN5A gene, encoding the cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5, cause inherited arrhythmias (7). In this article, we review the periodic paralyses as the foundation for studies of channelopathies, and we consider the ever-increasing number of mutations in brain sodium channels that cause genetic forms of epilepsy, autism, and cognitive dysfunction. Recent review articles have covered other aspects of this large field, including inherited pain syndromes (8), inherited cardiac arrhythmias (9–11), and channelopathies caused by mutations in the non-pore-forming auxiliary β-subunits of sodium channels (12, 13).

1.1. The Sodium Channel Protein Complex

Voltage-gated sodium channels initiate and conduct action potentials in nerve and muscle cells (14). Sodium channel proteins isolated from nerve and muscle are complexes of a large, pore-forming α-subunit of 250 kDa with one or two β-subunits of 30–40 kDa (FIGURE 1A; Ref. 16). The α-subunits are composed of 24 transmembrane segments organized in four homologous domains containing six transmembrane segments in each (FIGURE 1B; Ref. 16). The short intracellular linker between domains III and IV serves as the inactivation gate (FIGURE 1, B and C). The three-dimensional structure of the core functional unit of the sodium channel was first revealed by X-ray crystallographic studies of the homotetrameric ancestral bacterial sodium channel NaVAb (FIGURE 1, D–F; Ref. 17). As expected from structures of voltage-gated potassium channels, the pore is formed by the S5 and S6 segments in the center of a square array of four subunits, and the voltage sensor is a bundle of four transmembrane α-helices (S1–S4), connected to the pore by the S4–S5 linker (17, 19). The structures of eukaryotic nerve and skeletal muscle sodium channels have been determined by cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), including human sodium channels from nerve and skeletal muscle (FIGURE 1, G and H; Refs. 18, 20). The structure of the functional core of these channels is virtually identical to NaVAb (17), which was used as a search template to solve the initial structure (20). These detailed analyses of eukaryotic sodium channels reveal the structure of the complex of α- and β-subunits, the conformations of the selectivity filter and fast inactivation gate, and the structures of portions of the large intracellular and extracellular domains that are not present in the bacterial sodium channels.

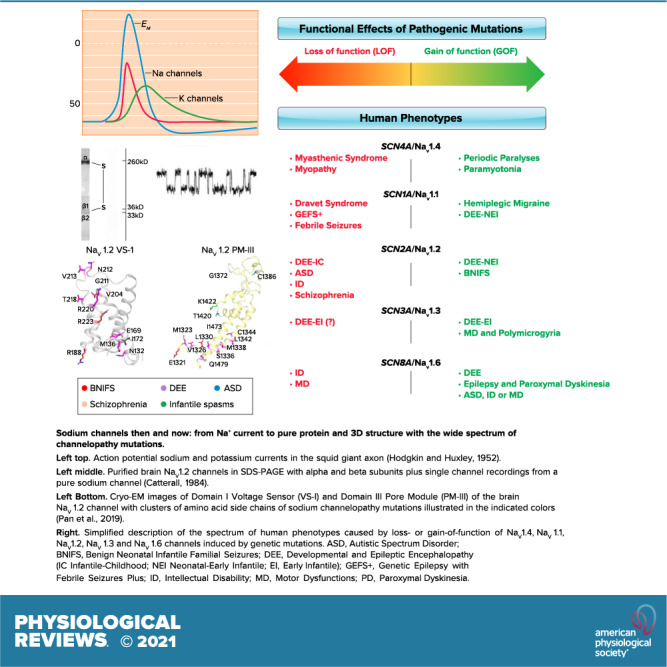

FIGURE 1.

Structure of voltage-gated sodium channels revealed step by step over >30 yr. A: cartoon model of purified brain sodium channels with α- and β-subunits circa 1986. ScTx, scorpion toxin; TTX, tetrodotoxin; P, protein phosphorylation. B: transmembrane folding diagram of the sodium channel α-subunit with key functional domains indicated circa 2000. Blue circle with h, inactivation particle with isoleucine, phenylalanine, methionine (IFM) motif; empty blue circles, inactivation gate receptor. C: structure of the inactivation gate peptide of the brain NaV1.2 channel determined by NMR. D: top view of the structure of NaVAb determined by X-ray crystallography circa 2011. Blue, pore module; green, voltage sensors. E: structure of the pore of NaVAb. F: structure of the voltage sensor of NaVAb. G: structure of NaV1.4 with β1-subunit circa 2018. The domain III–IV linker (brown) serves as the fast inactivation gate. H: close-up of the IFM motif of the inactivation gate (brown) interacting with its receptor. A: adapted from Ref. 15 with permission from Annual Review of Biochemistry. B and C: adapted from Ref. 16 with permission from Neuron. D–F: adapted from Ref. 17 with permission from Nature. G and H: adapted from Ref. 18 with permission from Science.

Numerous proteins can interact with the core sodium channel complex formed by α- and β-subunits, leading to heterogeneous multimolecular complexes that can be specific of different cell types or different cell subcompartments (9, 21–24). These interactions play a role in trafficking and localization of the core channel complex, as well as in modulation of its functional properties, often by means of posttranslational modifications. They can also be implicated in rescuing folding/trafficking defective mutants, as we have outlined below in sect. 3.3. Interestingly, recent studies of cardiac NaV1.5 channels indicate that there can also be interactions of α-subunits: dimers of α-subunits can be isolated from cardiac tissue, and activities consistent with the existence of functional dimers are observed upon expression in noncardiac cells (25). The two channel proteins in these dimers are functionally coupled, and mutations in one channel protein can influence the biophysical and functional properties of its partner (25, 26). Biochemical studies revealed that NaV1.1 and NaV1.2 channels can also form dimers (25). These surprising findings could have implications for recessive NaV1.1 and NaV1.2 sodium channelopathies, in which wild-type (WT) and mutant sodium channels are coexpressed in neurons and other cell types in vivo. Although some of the complexity of functional phenotypes observed in sodium channelopathies may arise from changes in interaction with associated proteins and functional dimerization of α-subunits, we do not review them further here because they have been less studied in comparison with the direct effect of mutations of the core sodium channel complex, and some defective interactions implicated in channelopathies have been recently reviewed (22, 24).

1.2. Structural Basis for Sodium Channel Function

Detailed structure-function studies using mutagenesis, electrophysiology, and molecular modeling have given a two-dimensional map of the functional parts of sodium channels (FIGURE 1B; Refs. 16, 27). Channelopathy mutations affect all aspects of sodium channel function. The structural and molecular mechanisms for sodium channel function are introduced in the paragraphs below, and the impact of different classes of channelopathy mutations are considered in the subsequent sections.

1.2.1. Voltage-dependent activation.

Voltage-dependent activation of sodium channels is initiated by voltage-driven outward movement of the positive gating charges, usually arginine residues, in the S4 transmembrane segments of the voltage sensors (16, 28, 29). The voltage sensor is a four-helix bundle with a substantial aqueous cleft that faces the extracellular milieu (FIGURE 1F). The gating charges in the S4 segment are usually arginine residues spaced at three-residue intervals, which span the membrane (R1–R4; FIGURE 1F). Upon depolarization, the S4 segment moves outward, exchanging ion pair partners and transporting the arginine gating charges through the hydrophobic constriction site (HCS; FIGURE 1F), which serves to seal the voltage sensor and prevent transmembrane movement of water and ions. Changes in membrane potential drive the S4 segment inward and outward in response to hyperpolarization and depolarization, moving the gating charges through the HCS and across the complete transmembrane electric field. This “sliding-helix” mechanism of gating charge movement (15) has been confirmed for sodium channels by extensive mutagenesis, disulfide locking, molecular modeling, and most recently determination of the high-resolution structure of NaVAb by cryo-EM (19, 30–35). Similar experiments on potassium channels led to a consensus model for this voltage-sensing mechanism (36). This outward movement of the S4 segment initiates a conformational change in the voltage sensor, which is transmitted to the pore by a twisting motion of the S4–S5 linker (17, 34, 35). The intracellular ends of the S6 segments cross and interact closely to form the closed activation gate, which opens in an irislike motion in response to the voltage-dependent conformational changes in the voltage sensor (17, 19, 34, 37, 38). Structures of the sodium channel in closed and open states reveal a substantial movement of the amino acid side chains at the intracellular ends of the S6 segments, from a closed conformation with an orifice of <1 Å to an open conformation with an orifice of 8.5 Å (37) to 10.5 Å (38). Determination of the structure of the resting state of a voltage-gated sodium channel fits closely with the expectations of this gating model and provides a complete picture of voltage sensing, electromechanical coupling, and pore opening at the atomic level (34). Currents generated by the activation of sodium channels are studied with voltage-clamp experiments, in which the transmembrane potential is controlled and the current elicited at different potentials is recorded (FIGURE 2A).

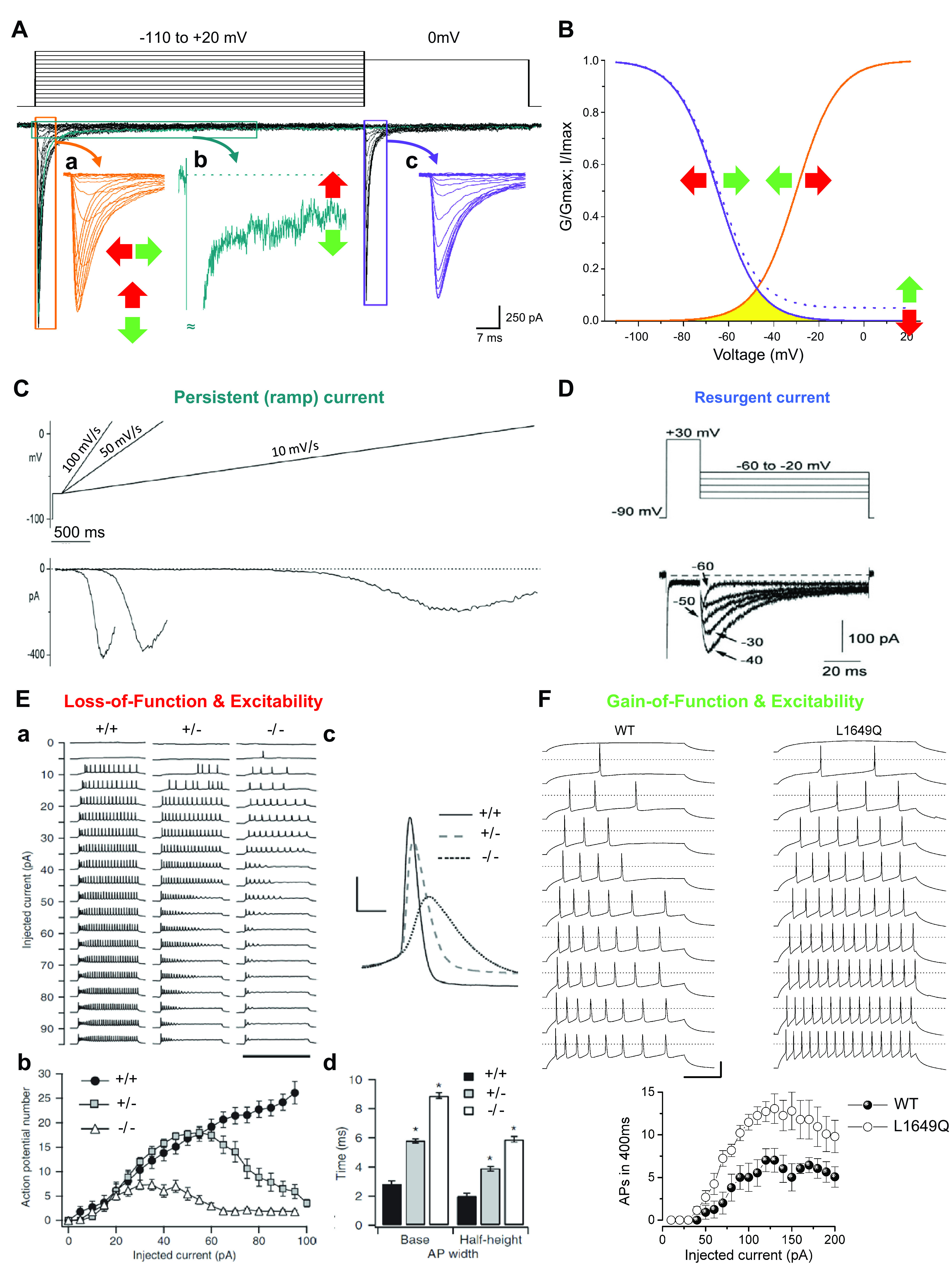

FIGURE 2.

Functional properties of sodium channels. Functional properties and their modifications induced by mutations involved in channelopathies are studied by performing voltage-clamp experiments that follow the general methods introduced by Hodgkin and Huxley in their seminal work (39). In modern experiments aimed at identifying functional effects of mutations, sodium channels are often expressed in transfected cell lines that do not have endogenous channels of interest, and currents are evoked controlling the membrane potential in voltage-clamp mode by means of the whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique. A: representative recordings of families of NaV1.1 sodium currents with the 2-pulse voltage protocol shown at top. Inward sodium currents are a negative quantity by convention and therefore plotted downward. The first pulse is a step depolarization at different potentials (up to +20 mV) activating inward sodium currents (inset a), which then undergo fast inactivation during the 100-ms depolarization. These recordings determine the maximal current amplitude and the kinetics of fast inactivation from the open state within a few milliseconds. Current amplitude can be increased by gain-of-function mutations (depicted by green vertical arrow) or decreased by loss-of-function mutations (red vertical arrow). Sodium currents can be prolonged by gain-of-function mutations (green horizontal arrow) or shortened by loss-of-function mutations (red horizontal arrow). The small fraction of current with slower inactivation is called persistent sodium current (inset b, in which a single trace is shown). Gain-of-function mutations can increase its amplitude, whereas loss-of-function mutations can decrease it. The second pulse at 0 mV evokes sodium currents (inset c) whose amplitude decreases according to the amount of fast inactivation induced by the first pulse. Scale bars refer to the black traces. Similar voltage protocols with longer depolarizations (up to tens of seconds) can be used to study slow inactivation. B: the activation curve (orange) is obtained by plotting the normalized peak conductance (G/Gmax) of the currents in inset a as a function of the stimulus potential. The fast inactivation curve (violet) is obtained by plotting the normalized peak values of the currents (I/Imax) displayed in inset c as a function of the potential of the first pulse. Gain- and loss-of-function mutations can induce shifts of the curves (horizontal arrows). The current elicited at membrane potentials in which activation and inactivation curves overlap (yellow area) is called window current. When there is persistent current, the inactivation curve shows a baseline at positive voltages (solid line, 0% persistent current; dashed line, 5% persistent current). C: the persistent current can also be elicited with slow depolarizing voltage ramps that inactivate the fast transient current; of note, relatively fast voltage ramps can elicit a mixed persistent and fast current, whose amplitude depends on the kinetics of fast inactivation, and very slow voltage ramps can induce inactivation of persistent current. Modified from Ref. 40 with permission from Neuropharmacology. D: the resurgent sodium current is generated in some cell types during repolarizations from positive voltages to moderately negative potentials, and gain-of-function mutations can increase it, whereas loss-of-function mutations can decrease it. Modified from Ref. 41 with permission from Journal of Neuroscience. E: loss-of-function mutations of sodium channels decrease neuronal excitability. a: Loss of action potential firing in GABAergic neurons from Scn1a-knockout mice. Action potential discharges, recorded in current-clamp mode with the whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique, elicited by injecting depolarizing currents of increasing amplitude in control (+/+), heterozygote Scn1a+/− (+/−), and homozygote Scn1a−/− (−/−) GABAergic neurons. b: Input-output relationships of the number of action potentials vs. the injected current show a large reduction of excitability in Scn1a−/− neurons and less severe reduction in Scn1a+/− neurons. The rheobase (i.e., the minimum depolarizing current that elicits an action potential) is not modified in this model, but loss of function of some sodium channels can increase it. c: Representative single action potentials, recorded for each genotype of GABAergic neurons and elicited by the same injected current amplitude (35 pA), show reduced amplitude with NaV1.1 loss of function, as well as increased width and half-width, which are defined as the width at the base and at the half-maximum amplitude of the action potential (AP). d: Modified from Ref. 42 with permission from Nature Neuroscience. F: action potential discharges recorded in cultured GABAergic neurons transfected with wild-type (WT) NaV1.1 or the familial hemiplegic migraine gain-of-function L1649Q mutant show increased excitability when the mutant is expressed, as quantified in the input-output relationships (bottom). Modified from Ref. 43 with permission from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Sodium channel gain of function can also decrease rheobase and modify features of action potentials (e.g., amplitude, slope, width); not shown.

A surprising finding from structure-function studies of both sodium and potassium channels was the ability of the voltage sensor to serve as a proton-conducting (44) or cation-conducting (45, 46) pathway after mutation of the arginine gating charges. Neutralization of the gating charges of voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels causes a voltage-dependent leak current to flow through the mutant voltage sensors continuously. These gating pore currents (or omega currents) are voltage dependent because the leak occurs only when the mutant residue replaces the arginine gating charge in the HCS that seals the voltage sensor against transmembrane ion movement (45, 46). In sodium channels, mutation of the R1 and R2 gating charges causes gating pore current in the resting state, whereas mutation of R2 and R3 gives gating pore current in the activated and inactivated states (45). These characteristics are consistent with the sliding-helix model of voltage sensor function, which predicts that the gating charges slide through the HCS in sequence during activation and deactivation of the voltage sensor (45). Mutant gating pores can be highly selective for protons when histidine is substituted for arginine (44), but they are not highly selective among monovalent cations when other amino acid substitutions are present (45–47). However, mutant gating pores often have a high conductance to guanidine (46, 47), likely because it fits well in the space left by removal of the guanidine-containing arginine side chain.

1.2.2. Sodium conductance and selectivity.

Sodium conductance is mediated by the pore domain formed by the S5 and S6 segments and the P loop between them. As for potassium channels, sodium selectivity is mediated by the P loops in the four pore domains of sodium channels, which interact with Na+ as it approaches and enters the ion selectivity filter (17, 48–50). However, in sharp contrast to potassium channels, the outward-facing edge of the ion selectivity filter is composed of a square array of four glutamate residues in bacterial NaV channels (17) or a square array of four different amino acid residues, Asp-Glu-Lys-Ala, in vertebrate NaV channels (18). This high-field strength site partially dehydrates the approaching Na+ ion and allows only Na+ to pass efficiently (48). A dunking motion of the glutamate residues accompanies the partial dehydration of Na+ and its inward movement through the selectivity filter (48).

1.2.3. Fast inactivation.

Within 1–2 ms after opening, the fast inactivation gate formed by the intracellular linker connecting domains III and IV folds into the pore and inactivates it (FIGURE 1, B and C; Refs. 16, 27). In voltage-clamp experiments, some properties of fast inactivation can be studied by analyzing the current decay during step depolarizations and the decrease of the amplitude of the current elicited by the second depolarizing pulse in a two-pulse protocol (FIGURE 2, A and B). Fast inactivation does not have its own intrinsic voltage sensor. Structure-function studies indicate that outward movement of the gating charges in the S4 segment of the voltage sensor in domain IV plays a key role in coupling activation to fast inactivation (51–54). A series of key amino acid residues in this linker, Ile-Phe-Met, serves as the classically defined “inactivation particle,” which folds into the inner pore domain and blocks sodium conductance (55, 56). The structure of the fast inactivation gate contains an α-helical motif preceded by two turns that present the key interacting residues in the Ile-Phe-Met motif to the inner pore domain, where they are bound and close the pore (FIGURE 1, C and H; Refs. 18, 57). The “receptor” that binds the inactivation gate to the intracellular end of the pore is formed by amino acid residues in the S4–S5 linkers in domains III and IV and the intracellular end of the S6 segment in domain IV (18, 20, 58–62).

The intracellular COOH-terminal domain can modulate fast inactivation (63), possibly interacting with the fast inactivation gate (64). Consistently, this domain is implicated in modulations that modify inactivation properties, including G protein βγ-subunits that increase the persistent sodium current (65). The persistent current is a slowly inactivating fraction of the sodium current, which is generated because fast inactivation is not complete, even at very depolarized potentials (66) (FIGURE 2, A and C). Its kinetics of inactivation shows multiple time constants, and there is a residual component even after depolarizations of tens of seconds (67). Although it is often a small fraction of the peak transient sodium current, it can have important effects on cellular excitability. Distinct from the persistent current, the window current is a noninactivating current generated in the sharp window of membrane potentials where the curves of voltage dependence of fast inactivation and activation overlap, and it is important for boosting subthreshold depolarizations (FIGURE 2B). Another subthreshold sodium current is the resurgent current, an unusual transient sodium current elicited by repolarizations that follow strong depolarizations and can contribute to spontaneous and high-frequency firing (41, 68) (FIGURE 2D). It has been proposed that this current is produced by a putative intracellular blocking factor that would bind to open sodium channels and prevent fast inactivation.

1.2.4. Slow inactivation.

During long single depolarizations or long trains of depolarizations, sodium channels enter a slow inactivated state, from which recovery requires prolonged repolarization (69). Slow inactivation has a structural basis different from fast inactivation. Slow inactivation of bacterial sodium channels is caused by an asymmetric collapse of the pore involving amino acid residues in the ion selectivity filter and the full length of the pore-lining S6 segments (19, 70, 71). This mechanism is conserved in vertebrate sodium channels, in which analogous amino acid residues in the selectivity filter and the pore-lining S6 segments undergo conformational changes in the slow inactivation process (69, 72–74). The close structural similarity in the core transmembrane regions of bacterial and mammalian sodium channels (<2 Å root mean square deviation in backbone structure) supports close similarity in the underlying mechanisms of slow inactivation.

These structure-function models of sodium channels derived from a combination of mutagenesis, electrophysiological analysis, and structural studies have provided valuable templates for understanding the deleterious effects of mutations that cause sodium channelopathies. Impairments of voltage-dependent activation, generation of gating pore current through the voltage sensor, altered coupling of activation to pore opening, and defects in ion conductance, fast inactivation, and slow inactivation have all been associated with channelopathies of skeletal muscle and brain sodium channels. These defects can have a direct effect on generation of action potentials and their features (FIGURE 2, E and F).

2. NaV1.4 AND PERIODIC PARALYSIS

The periodic paralyses are rare genetic diseases with a dominant pattern of inheritance within families (2, 75, 76). They cause episodic flaccid paralyses, sometimes accompanied by episodic stiffening of skeletal muscles, which are associated with a wide range of physiological and environmental factors, including exercise, temperature, and changes in serum potassium levels that result from exercise and food intake (2, 76, 77). As outlined below, these diseases are generally caused by heterozygous mutations in the SCN4A gene encoding the skeletal muscle sodium channel NaV1.4 (2, 76) (FIGURE 3).

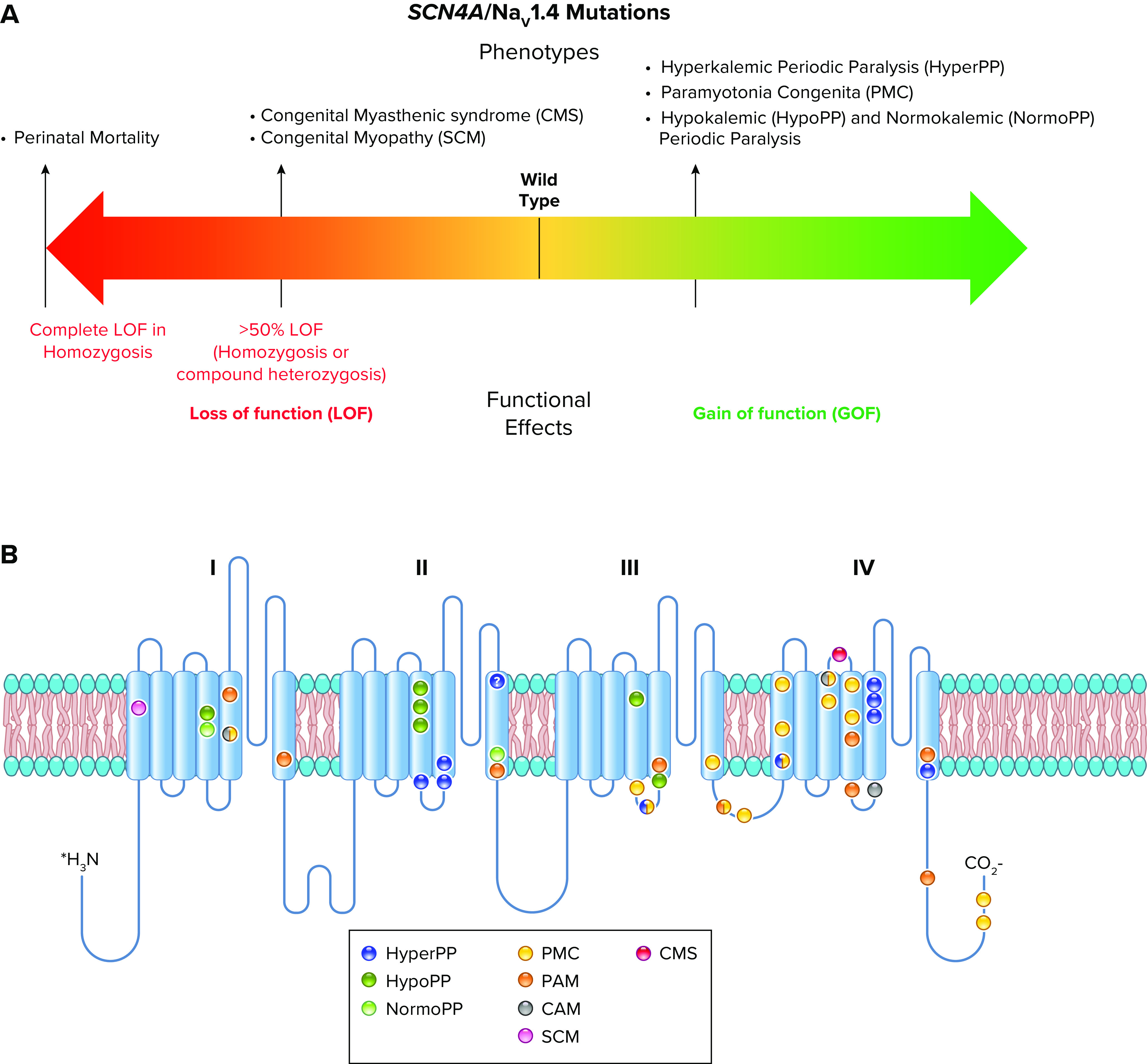

FIGURE 3.

Spectrum of mutations and phenotypes for SCN4A/NaV1.4. A: phenotypic spectrum. Most SCN4A mutations cause NaV1.4 gain of function with different mechanisms, including induction of gating pore current, leading to specific clinical entities. A minority of mutations cause loss of function, inducing clinical symptoms when the loss is >50% (homozygosis or compound heterozygosis). The few patients with complete loss-of-function mutations in homozygosis showed perinatal lethality. B: molecular map of SCN4A mutations color-coded as indicated: hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (HyperPP), hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HypoPP), normokalemic periodic paralysis (NormoPP), paramyotonia congenita (PMC), potassium-aggravated myotonia (PAM), cold-aggravated myotonia (CAM), congenital myopathy (SCM), and congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS).

2.1. Hyperkalemic Periodic Paralysis

In hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (HyperPP), affected individuals have episodes of flaccid paralysis associated with high levels of serum potassium (2, 76). Electrophysiological studies of skeletal muscle fibers from patients revealed impaired inactivation of the sodium current and increased persistent sodium current that caused depolarization, block of action potential generation, and flaccid paralysis (78). These studies implicated the skeletal muscle sodium channel as either a direct or indirect target of HyperPP mutations. Genetic mapping identified the SCN4A gene encoding the skeletal muscle NaV1.4 channel as a prime target of these mutations (79, 80). In landmark studies, Ptácek et al. (81) and Rojas et al (82) cloned and characterized mutations that cause HyperPP in the SCN4A gene encoding the skeletal muscle sodium channel NaV1.4, the first discovery of the genetic basis for an ion channelopathy. Sequencing of several mutations in this gene from individuals with HyperPP and their close relatives definitively identified SCN4A as the site of mutations that cause this disease (81). Mutations that cause HyperPP are concentrated in the S4–S5 linkers in domains II and III and in the S6 segments near the intracellular end of the pore in domain IV (FIGURE 4, A and B, blue; Ref. 83). These segments are crucial for coupling of voltage sensor movement to pore opening and for forming the receptor for the fast inactivation gate as it folds in and blocks the pore (18, 20, 58–62). Structure-function studies reveal that disruption of the protein interactions that keep the fast inactivation gate closed impairs fast inactivation, allows reopening of sodium channels, and causes persistent sodium currents (55, 56). Therefore, as expected from these structure-function studies, many HyperPP mutations impair fast inactivation (e.g., Refs. 84, 85). HyperPP mutations also impair slow inactivation (69, 86, 87). Mutations in distinct locations cause a variable mixture of impairment of fast and slow inactivation (86). These dual functional deficits may work together by first producing prolonged depolarization following action potentials due to impaired fast inactivation, which leads to persistent depolarization in the absence of effective slow inactivation.

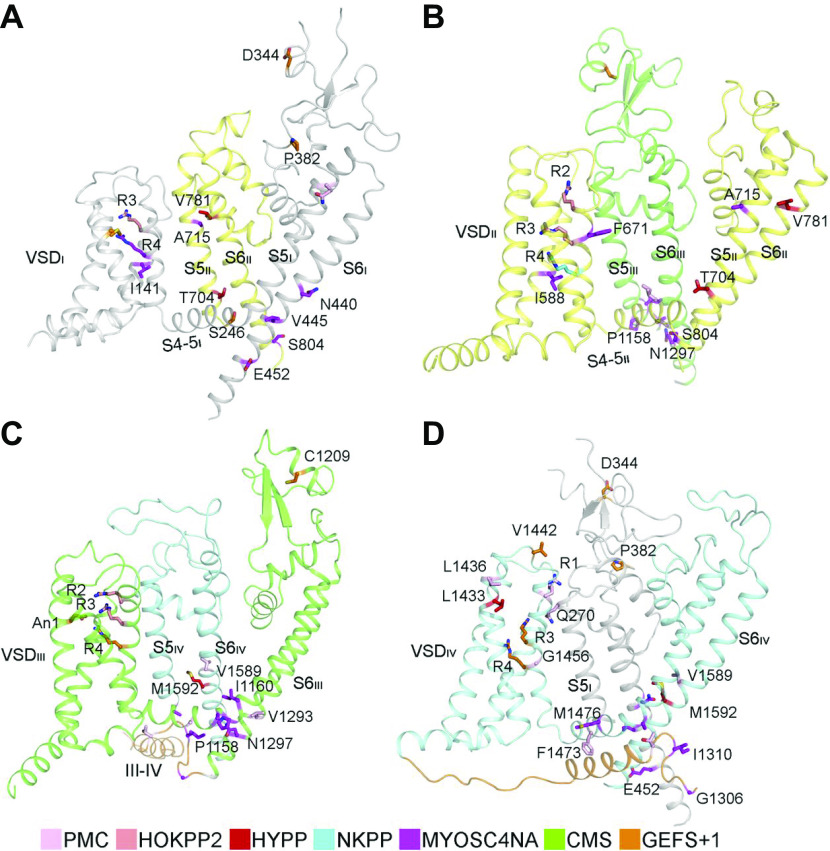

FIGURE 4.

Structural features of Nav1.4 mutations. A–D: structural location of periodic paralysis mutations. CMS, congenital myasthenic syndrome; GEFS + 1, generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus 1; HOKPP2, hypokalemic periodic paralysis; HYPP, hyperkalemic periodic paralysis; MYOSCN4A, myotonia caused by SCN4A mutations; NKPP, normokalemic periodic paralysis; PMC, paramyotonia congenita; VSD, voltage-sensing domain. Adapted from Ref. 18 with permission from Science.

2.2. Paramyotonia Congenita and Potassium Aggravated Myotonia

Paramyotonia congenita (PMC) causes episodic paralysis of skeletal muscle, which initially presents as stiffness and rigidity triggered or aggravated by low temperature and is often followed by flaccid paralysis and muscle weakness (88–90). PMC mutations mapped to the same gene as HyperPP (80) and cDNA cloning and sequencing of mutations from affected and unaffected members of the same families demonstrated that PMC is caused by mutations in the SCN4A gene encoding NaV1.4 like HyperPP (91, 92). PMC mutations are clustered in the inactivation gate and nearby transmembrane segments and in the S4–S5 linker in domain III (FIGURE 4, A and B; Ref. 83). They are also clustered in the S4 segment in domain IV, which is thought to trigger fast inactivation (91, 93). Physiological studies of muscle fibers dissected from patients exhibited an unusual persistent depolarization of myofibers, which was blocked by tetrodotoxin and therefore required the activity of the mutant sodium channels (94). Single-channel recordings revealed many late openings following depolarization of muscle fibers from PMC patients but not in fibers from control individuals (94). These results pointed to gain-of-function effects of PMC mutations on sodium channels. Electrophysiological analysis of the functional changes in the mutant NaV1.4 channel expressed from cDNA in cultured nonmuscle cells revealed impaired inactivation of the sodium currents, caused by a combination of slowed and less steeply voltage-dependent fast inactivation and accelerated recovery from fast inactivation (95–99). These functional changes would cause persistent sodium current and reopening of single sodium channels in cells expressing these mutants. These gain-of-function effects lead to generation of inappropriate trains of action potentials and to uncoordinated twitching or myotonia. Although these mutations impair inactivation and increase persistent sodium current, they do not cause an increase in resting sodium levels in muscle fibers; however, cold challenge during exercise does cause an increase in intracellular sodium levels (100). Increased intracellular sodium during the bursts of action potentials that drive forceful muscle contractions would reduce the driving force for sodium current, depolarize muscle fibers, and cause failure of action potential generation. These cellular events may lead to the flaccid paralysis that follows episodes of myotonia and muscle stiffening in PMC.

Potassium-aggravated myotonia (PAM) is a milder disease than PMC. Stiffness and myotonia are initiated during exercise, and they may persist for hours, but they are not followed by flaccid paralysis (83). Muscle stiffness is aggravated by elevated serum potassium but is unaffected by cold (83). Mutations that cause this disease are scattered along the intracellular surface of the sodium channel, especially in domain IV, and they include amino acid residues identified as important components of the fast inactivation gate and its receptor region (FIGURE 4, A and B; Ref. 83). The functional effects are milder than those that cause PMC, but there is one mutation in the fast inactivation gate that causes both diseases, depending on the family and the genetic backgrounds of the patients (101).

2.3. Hypokalemic and Normokalemic Periodic Paralysis

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HypoPP) causes episodic flaccid paralysis associated with low potassium levels in serum and high potassium levels in skeletal muscle (2, 76, 102). Muscle fibers are depolarized and have a high internal sodium concentration, which leads to loss of excitability (2, 76, 102). Mutations in the CACNAL1 gene encoding the skeletal muscle calcium channel CaV1.1 are the most frequent cause of HypoPP (103). In contrast to the broad range of mutations that cause HyperPP and PMC, mutations that cause HypoPP always change the first or second arginine gating charge in an S4 segment to a neutral amino acid residue (83, 104, 105). Introduction of a HypoPP mutation into mice reproduced the potassium-sensitive paralysis and weakness characteristic of HypoPP, further confirming the causative role of these gating charge mutations in the disease (106). Surprisingly, analogous mutations in the first or second gating charges (R1 and R2) in the S4 segment of the NaV1.4 skeletal muscle sodium channel also cause this disease in humans and mice (FIGURE 4, A and B; Refs. 107–109), further highlighting the pathogenic role of these gating charge mutations in HypoPP. The rare related disease normokalemic periodic paralysis (NormoPP) causes similar flaccid paralysis at normal levels of serum potassium (110). Remarkably, it is caused by mutations of the gating charge arginine in the third (R3) position in S4 segment of NaV1.4 (110). This characteristic genetic feature that is shared by HypoPP and NormoPP mutations suggests a unique common mechanism of action of these mutations that are exclusively in gating charges. However, even though HypoPP mutations have a variety of effects on fast and slow inactivation of NaV1.4 channels, none of these effects is potent enough to be the primary cause of the symptoms of HypoPP or NormoPP (108, 111, 112).

The enigma of the mechanism of HypoPP and NormoPP was resolved by discovery of gating pore currents that are induced by HypoPP and NormoPP mutations (47, 113–116). As described above in sect. 1.2, mutation of gating charge arginine residues to neutral amino acid residues can cause gating pore current through the mutant voltage sensor. On the basis of these earlier findings, it was natural to hypothesize that HypoPP mutations cause pathogenic gating pore current. As expected from this hypothesis, pathogenic gating pore currents could be detected for HypoPP mutations in NaV1.4 (114, 115). The inward currents conducted by the pathogenic gating pores are in the range of 1% of the peak sodium current, and they are nonselective among monovalent cations (47, 114–116). In contrast to the nonselectivity among monovalent cations, mutants having His substituted for Arg often conduct protons selectively (115, 116). HypoPP mutations in NaV1.4 channels are located in the R1 and R2 gating charges, and they cause gating pore current in the resting state (114). Even though the gating pore currents are small, they are constant, and calculations indicate a large effect on sodium entry into muscle fibers, consistent with the increased intracellular sodium levels and depolarized membrane potentials in HypoPP muscle (114, 115).

In contrast to HypoPP, mutations that cause NormoPP specifically neutralize the R3 gating charge (110). They cause gating pore current in the activated and inactivated states, because the R3 gating charge is located in or near the HCS in the activated state of the voltage sensor (113). The voltage dependence of pathogenic gating pore current is complex: it is activated at strongly depolarized potentials but deactivated only at much more negative potentials resulting in a hysteresis loop (113). The low conductance of the mutant gating pore would not be pathogenic if the gating pore were only open briefly during an action potential. However, voltage-clamp analysis showed that the mutant gating pore is open in both activated and slow-inactivated NaV1.4 channels (113). Because slow inactivation accumulates during the long trains of action potentials that induce forceful muscle contraction, the mutant gating pore is open for sufficiently long intervals to cause periodic paralysis and degeneration of muscle fibers.

HypoPP and NormoPP mutations have been introduced into the bacterial sodium channel NaVAb to study the structural basis for gating pore current (117). The central pore currents and gating pore currents generated by these mutants were analogous to those observed in pathogenic mutations in NaV1.4 channels (FIGURE 5, A and B; Ref. 117). The central pore currents were typical for sodium channels (FIGURE 5, A and B, left). However, the mutants exhibited marked gating pore currents (FIGURE 5, A and B, center and right). The HypoPP mutant R2S conducted gating pore leak currents at negative membrane potentials in the resting state (FIGURE 5A, center and right, blue), whereas the R3G mutant conducted gating pore leak currents at positive potentials in the activated state (FIGURE 5B, center and right, red). As expected from physiological studies, these mutations cause a voltage-dependent transmembrane conductance pathway through the voltage sensor itself that is clearly observed by X-ray crystallography (FIGURE 5C). The diameter of the pathogenic gating pore is 2–3 Å, consistent with conductance of dehydrated sodium ions at the low rate characteristic of gating pore current. The complete water-filled pathway through which the sodium ion moves is highlighted in magenta in FIGURE 4C, right, as revealed by analysis with the program MOLE (117).

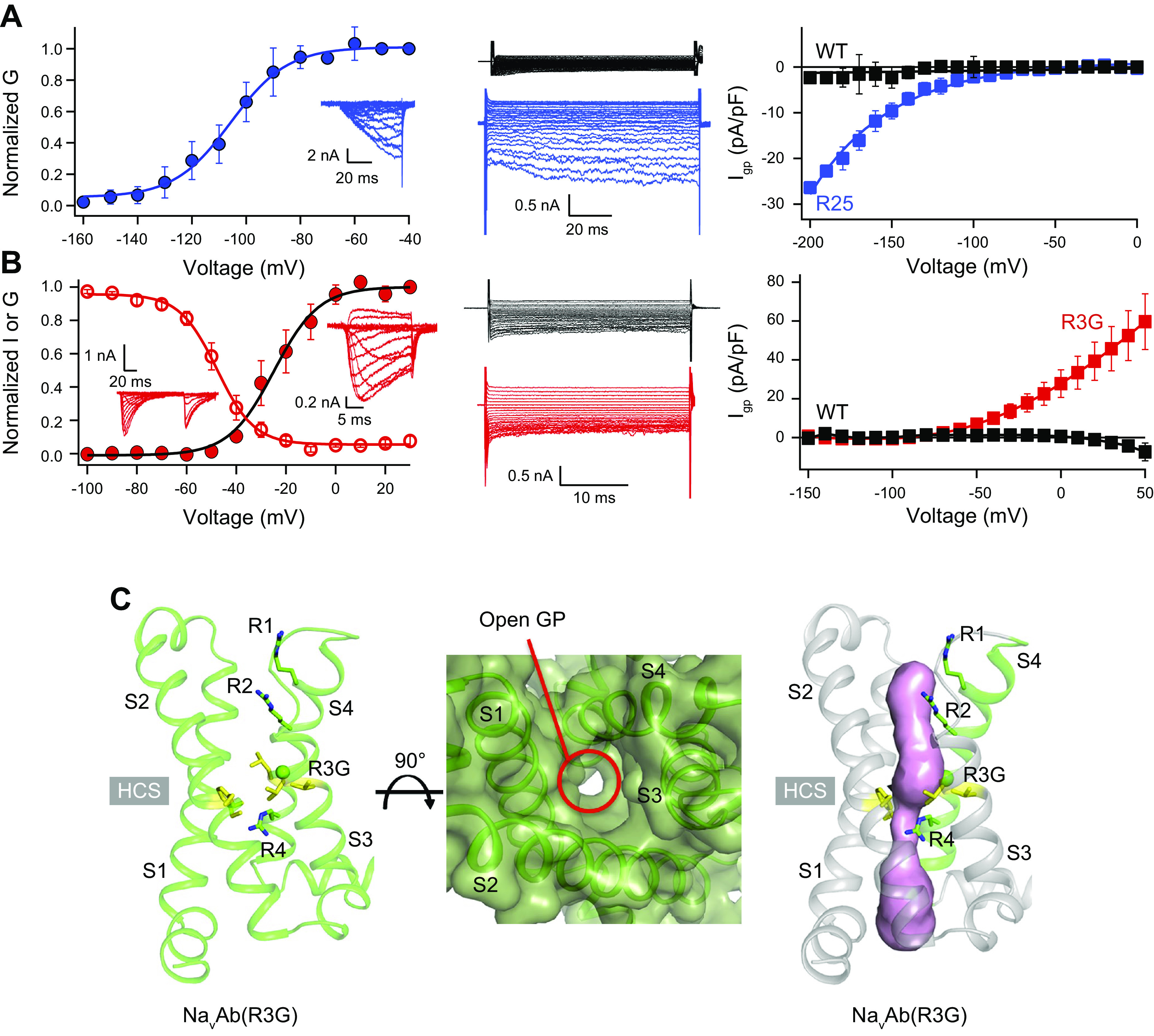

FIGURE 5.

Pathogenic gating pore current and structure. A, left: central pore Na+ currents (inset) and conductance (G)/voltage (V) curve for NavAb/R2S recorded during 200-ms depolarizations from −200 mV to the indicated potentials. Center: leak Na+ currents for wild-type (WT; black) and NavAb/R2S (blue). Note the larger negative leak currents in NavAb/R2S due to gating pore current. Right: current (Igp)/V curves for nonlinear leak currents for NavAb/R2S (blue) or NavAb/WT (black) elicited by depolarization from −100 mV to the indicated potentials. B, left: central pore Na+ currents (inset) and G/V curve for NavAb/R3G from a holding potential of −160 mV (filled circles). Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation (open circles) for NavAb/R3G. Center: leak Na+ currents for NaVAb/R3G (red) or NaVAb/WT (black) for voltage steps from 0 mV to the indicated potentials. Right: Igp/V curves for nonlinear leak currents for NavAb/R3G (red) or NaVAb/WT (black, n = 11). Note the larger positive leak currents in NavAb/R3G due to gating pore current. C: structure of a pathogenic gating pore (GP) in a normokalemic periodic paralysis (NormoPP) mutation. Magenta shading, water-accessible space determined by MOLE2. HCS, hydrophobic constriction site; R1–R4, gating charges; S1–S4, transmembrane segments. Adapted from Ref. 117 with permission from Nature.

Although gating pore current is nonselective, its primary pathogenic effects are caused by inward leak of Na+. Quantitative estimates indicate that entry of Na+ through the open gating pore would increase the resting leak of Na+ >2-fold and possibly as much as 10-fold (47, 114–116). This increase in inward leak of Na+ causes elevation of intracellular Na+ from ∼15 mM in control subjects to a range of 19–25 mM in patients with different mutations (118). Muscle fibers are also depolarized from −87 mV in control subjects to a range of −74 mV to −77 mV in patients (118). These deficits in patients were significantly worsened by local cooling of muscle fibers, which had no significant effect on control subjects. The alterations in ion gradients and membrane potential also exacerbate a bistable state of excitability, in which the membrane potential jumps from hyperpolarized to depolarized levels in muscle fibers from patients much more than in control subjects (118). Similar effects were observed in a mouse model of NaV1.4 HypoPP, including gating pore current, persistent depolarization, impaired action potential generation, and episodic weakness without myotonia (109). Although mutations in HypoPP are heterozygous, the gating pore current of the defective sodium channel causes dominant-negative physiological impairment of action potential firing by the wild-type sodium channels through reduction of the sodium gradient and inactivation by chronic depolarization. Low extracellular potassium levels contribute to episodes of flaccid paralysis in two parallel ways. First, low potassium reduces the effectiveness of sodium efflux mediated by the Na+-K+-ATPase, which exchanges extracellular potassium for intracellular sodium. This effect exacerbates the increase in intracellular sodium and membrane depolarization. Second, the reduced extracellular potassium increases the shift to the depolarized state by changing the ratio of the bistable hyperpolarized and depolarized states of membrane potential (118).

2.4. Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome and Congenital Myopathy

Myasthenias are characterized by development of weakness and fatigue during continuous use of skeletal muscles (119, 120). Most of the myasthenia syndromes are caused by failure of synaptic transmission, similar to myasthenia gravis (119, 120). However, rare cases of failure of action potential firing downstream of synaptic transmission have been discovered (119, 120). The congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS) is a recessively inherited disease most often caused by homozygous mutations that neutralize a gating charge Arg in the S4 segment in domain IV of NaV1.4 (121, 122). Similar symptoms have been observed in patients with heterozygous mutations in the S4–S5 linker in domain I and the S4 segment and S3–S4 linker in domain IV (123, 124). These mutations cause a large negative shift in the voltage dependence of fast inactivation, slower recovery from inactivation, and, in some cases, dramatically accelerated slow inactivation (121, 122). Altogether, these mutations greatly reduce the sodium current in transfected cells and impair action potential firing in skeletal muscle fibers (77). Their effects are most pronounced during sustained trains of action potentials, which trigger forceful muscle contraction. Early in an action potential train, generation of action potentials is nearly normal; however, as the train continues, increasing numbers of the mutant and wild-type sodium channels enter the fast- and slow-inactivated states, and eventually action potential generation fails, causing fatigue (77).

Congenital myopathy is characterized by neonatal or early-onset weakness (125). It is caused by mutations in many genes. Fewer than 20 families worldwide have been identified with congenital myopathy caused by recessive SCN4A mutations (126). The mutations that have been analyzed have loss-of-function phenotypes, including complete or nearly complete loss of functional expression and large positive shifts in the voltage dependence of channel activation (126). The degree of impairment of muscle function correlates with the extent of loss of function of the mutant NaV1.4 channels. The inheritance of full loss-of-function mutations on both SCN4A alleles causes a particularly severe phenotype resulting in early lethality.

2.5. Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Periodic Paralysis

The periodic paralyses have characteristic differences in their effects on action potential sodium currents and on sodium leak, which determine the pathology of these muscle diseases (77). Gain-of-function mutations cause HyperPP and PMC by producing NaV1.4 channels that are hyperactive, conduct excess persistent sodium current, and/or reopen frequently after inactivation. In HyperPP, these functional effects at the cellular level cause repetitive action potential firing leading to sustained depolarization, inactivation of both wild-type and mutant NaV1.4 channels, and episodes of weakness or flaccid paralysis (127). In PMC, changes in the kinetics of fast inactivation slow its onset and accelerate its recovery, thereby producing mutant sodium channels that are ready to reactivate immediately upon repolarization from the preceding action potential. These changes lead to inappropriate repetitive firing of action potentials that cause stiffness, the clinical hallmark of myotonia (77).

The pathogenesis of HypoPP and NormoPP is remarkably different from HyperPP and PMC (77, 106, 109, 113–115). Mutations in the R1, R2, and R3 gating charges cause pathogenic gating pore currents, which leak protons and/or sodium into the cell, reduce the sodium gradient, depolarize the cell, and inactivate both wild-type and mutant NaV1.4 channels because of depolarization. The constant inward gating pore current destabilizes the bistable resting membrane potential in skeletal muscle and causes oscillating changes that impair the electrophysiological stability of the muscle fiber (77). Gating pore current is a gain-of-function effect at the molecular level, but it causes loss of contractile function at the cellular level by these diverse mechanisms. Adult patients with HypoPP and NormoPP experience pathological changes in their skeletal muscle fibers with advancing age, and a similar vacuolar pathology with disruption of transverse tubules and triad junctions is observed in mice bearing a HypoPP mutation in CaV1.1 (106), but the long-term outcomes of sodium channel HypoPP mutations in skeletal muscle of mutant mice have not yet been studied in detail. In humans, it is likely that the prolonged elevation of intracellular sodium and prolonged depolarization in HypoPP are responsible for local edema and changes of intracellular calcium signaling that cause degenerative cellular effects over time. Swelling and degeneration of muscle fibers increases progressively during the disease in response to altered ionic homeostasis. Repair mechanisms are not sufficient to counteract these cellular pathologies, leading to progressive failure of muscle function in addition to periodic paralysis.

3. BRAIN SODIUM CHANNELS: NaV1.1 AND EPILEPSY

Epilepsy is caused by excess synchronized action potential generation in the brain, which in turn depends directly on sodium channels (128). Sodium channels are the molecular targets for major antiepileptic drugs, including phenytoin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine (129). Therefore, it is not surprising that sodium channels are important molecular targets for mutations that cause epilepsy. Four sodium channel genes are expressed in the brain: NaV1.3, which is expressed primarily in embryonic and early postnatal brain, plus NaV1.1, NaV1.2, and NaV1.6, which are expressed increasingly in development and remain highly expressed in the mature brain (130–134). These three adult sodium channel types are all broadly expressed in the brain, but they differ in expression in different types of neurons and in localization in specific subcellular compartments of neurons. Early studies revealed differential expression of sodium channel types in hippocampal neurons, with NaV1.1 primarily in cell bodies and NaV1.2 primarily in dendrites and unmyelinated axons (135). NaV1.1 is the dominant sodium channel in interneurons (42), whereas NaV1.6 and NaV1.2 are the dominant sodium channel types in excitatory neurons and their myelinated axons (134, 136, 137). It is likely that the differential expression and subcellular localization of these sodium channel subtypes prevents effective functional compensation when one of these channel types is mutated, even though their functional properties are similar.

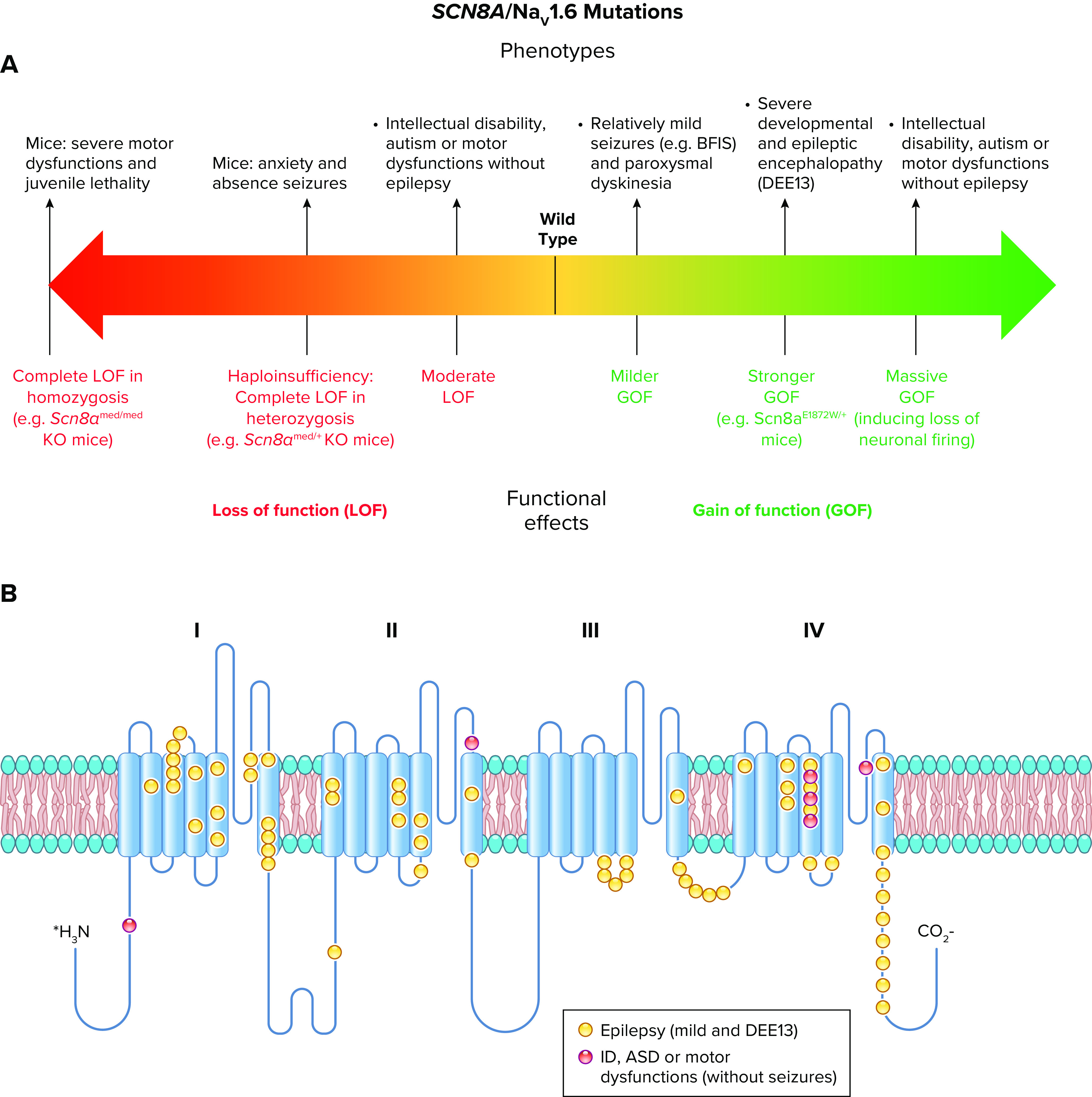

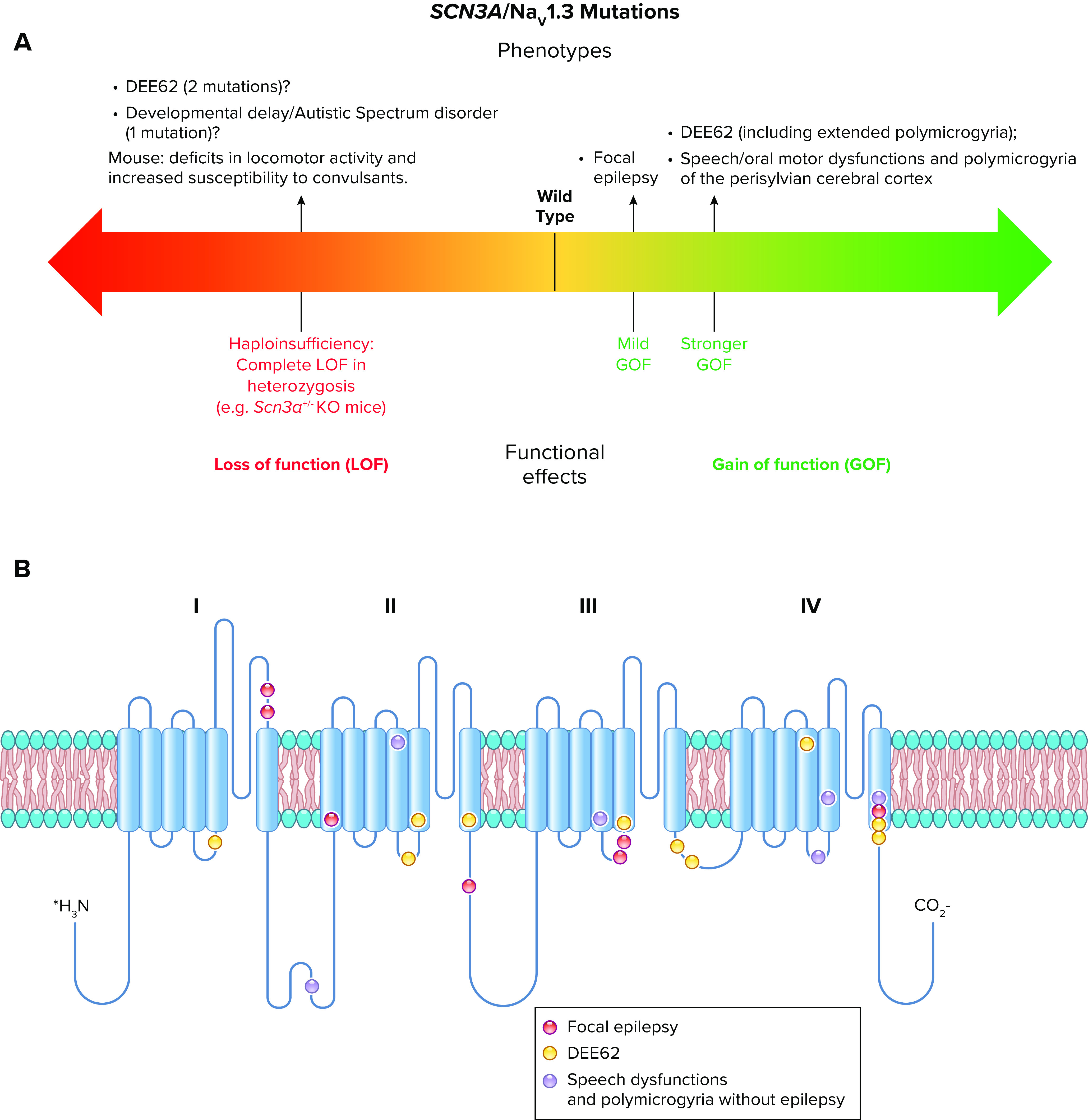

All sodium channel types that are highly expressed in the brain are targets for epilepsy mutations, which cause epileptic syndromes with a wide range of severity and comorbidities (128, 138, 139). The SCN1A gene that encodes the NaV1.1 channel is the most frequently mutated gene in sodium channel epilepsies, and these mutations cause a broad spectrum of epilepsy syndromes from mild febrile seizures to intractable, drug-resistant developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (140–142) (FIGURE 6).

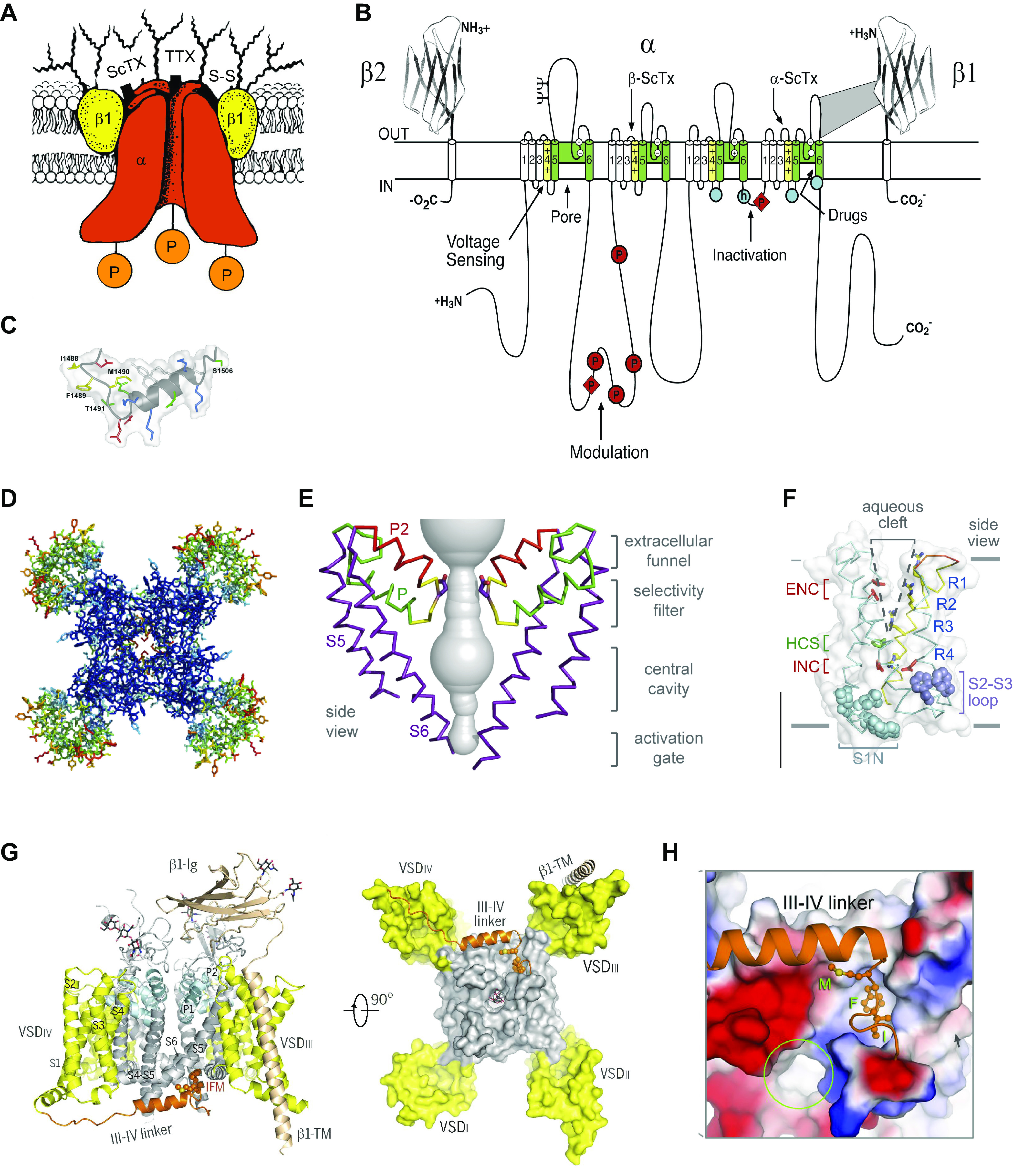

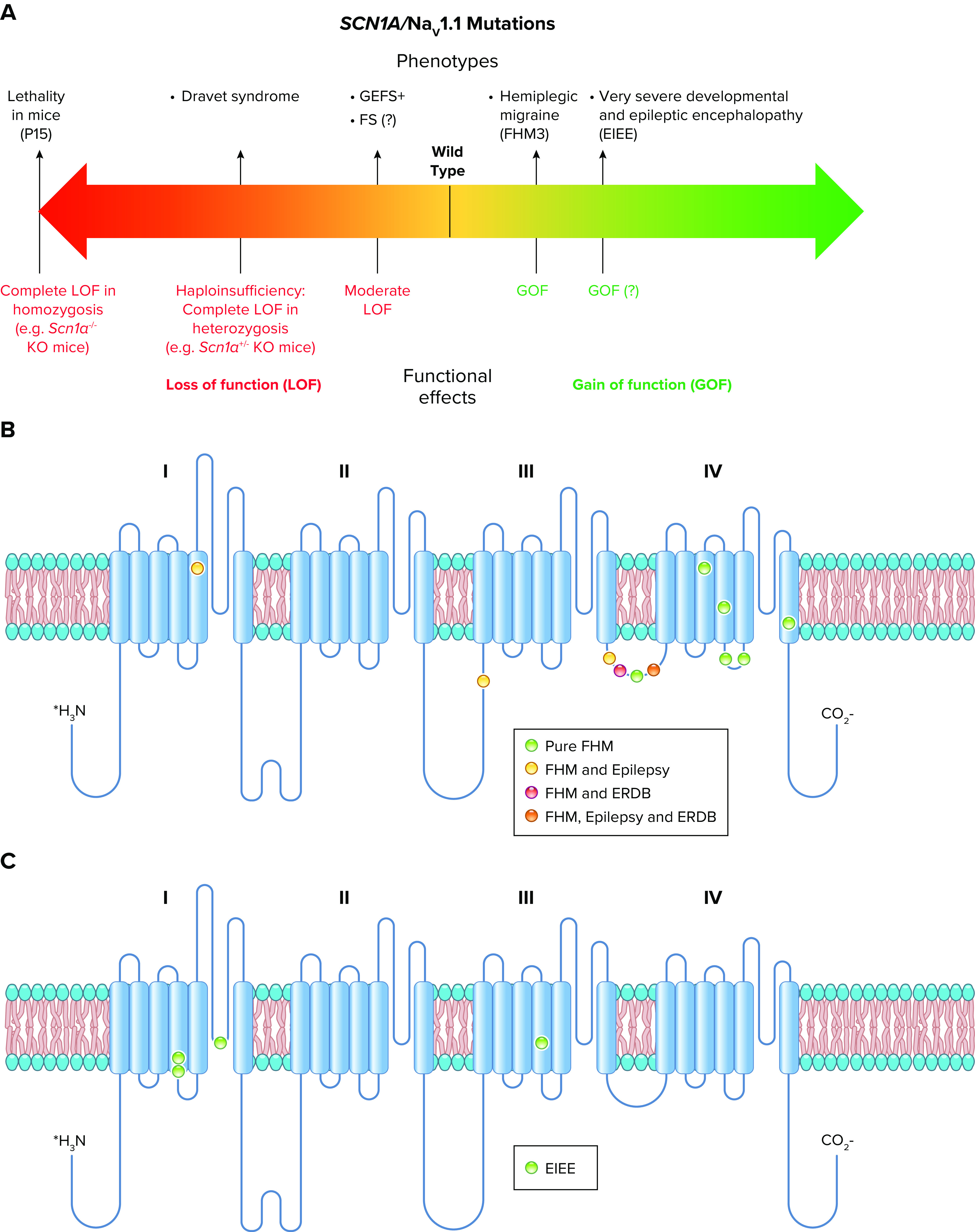

FIGURE 6.

Spectrum of mutations and phenotypes for SCN1A/NaV1.1. A: phenotypic spectrum of SCN1A mutations. Most SCN1A mutations cause epileptic phenotypes, including the severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy Dravet syndrome and the milder form genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+), which, however, shows large phenotypic variability and can include severe cases. SCN1A variants may be also involved in febrile seizure phenotypes (FS) that can include development of temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. These forms are caused by loss of function of NaV1.1 in heterozygosis, with often complete loss of function for Dravet syndrome, which is modeled by Scn1a+/− knockout mice. Gain of function of NaV1.1 has been identified for hemiplegic migraine (FHM3) mutations and proposed for mutations that cause an extremely severe early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE), although functional studies for this form have been performed for a single mutation. P15, postnatal day 15. B: molecular map of the NaV1.1 sodium channel with the location of hemiplegic migraine mutations color-coded as indicated (ERDB, elicited repetitive daily blindness). C: molecular map of the NaV1.1 sodium channel with the location of SCN1A EIEE mutations. Mutations causing other phenotypes are not shown because there are too many for a graphical representation.

3.1. Dravet Syndrome

Dravet syndrome is a developmental and epileptic encephalopathy that was first described clinically by Dr. Charlotte Dravet in Marseille, France in the late 1970s in an exceptional clinical investigation for its time (143, 144). Children with this disease develop normally for 6–9 mo. The first symptom of the disease is usually febrile seizures, which evolve over a few months to frequent spontaneous seizures that become drug resistant. Affected children lose developmental milestones that had previously been achieved, and they have severe cognitive impairment, autistic-like behaviors, ataxia, and disruption of circadian rhythms and sleep quality. Before the pathophysiology of the disease was well understood, >30% of children died prematurely from sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) or from accidents related to their seizures and impaired cognition. Even with modern care, >15% of affected individuals die prematurely (145), and most of those who survive to their teenage years have IQs in the range of 50 and require lifelong care (143, 144).

Dravet syndrome is caused by genetically dominant loss-of-function mutations in NaV1.1, which lead to deletions, truncations, nonsense codons, and single amino acid substitutions located throughout the coding exons of the gene (146–149). Mutations that cause the truncation of NaV1.1 lead to pure haploinsufficiency (150). More than 80% of patients diagnosed with Dravet syndrome have a mutation in NaV1.1 (145). Moreover, because only the 6-kb exons of the gene that code for the NaV1.1 protein are normally sequenced, it is likely that many of the other patients diagnosed with Dravet syndrome have mutations in the remaining 94% of the 100-kb SCN1A gene that cause loss of expression of the NaV1.1 protein and result in Dravet syndrome.

3.1.1. Loss of action potential firing in inhibitory interneurons in mouse models of Dravet syndrome.

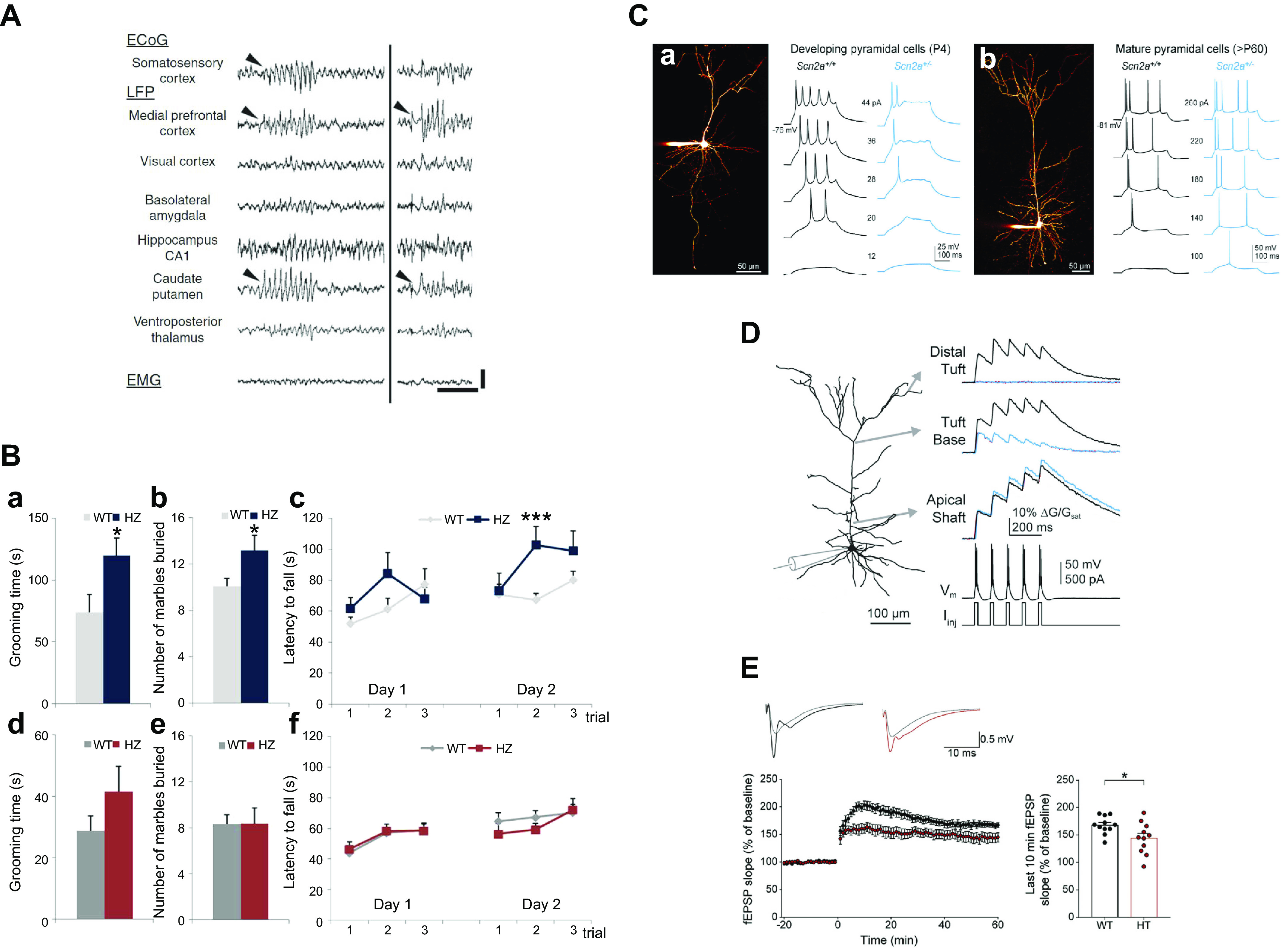

It was a paradox that loss-of-function mutations in a sodium channel would cause epilepsy. This paradox was resolved through studies of mouse models of Dravet syndrome, which have spontaneous generalized tonic-clonic seizures that are easily observed by video recording or by electroencephalography (FIGURE 7A; Refs. 42, 153, 154). Electrophysiological analysis of these mice revealed a selective loss of sodium currents and action potential firing in GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus (42, 140, 153, 154). Subsequent studies have shown a similar selective loss of electrical excitability in the GABAergic Purkinje neurons in the cerebellum, in the GABAergic neurons of the reticular nucleus of the thalamus, and in both parvalbumin-expressing and somatostatin-expressing interneurons in layer V of the cerebral cortex (FIGURE 7B; Refs. 151, 155–157). In each case, GABAergic inhibitory neurons were unable to sustain long trains of action potentials, which is required for effective control of the firing of excitatory neurons in neural circuits.

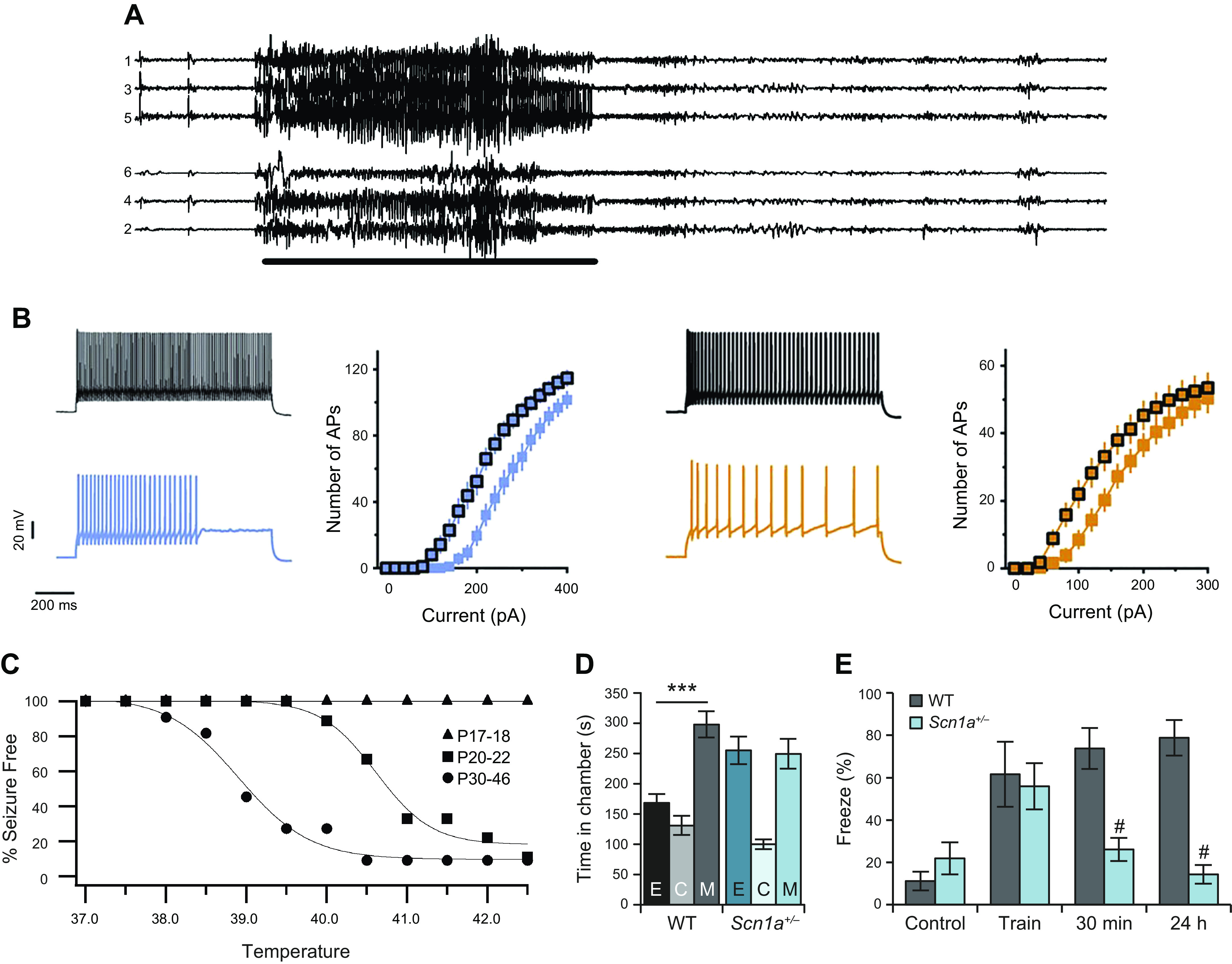

FIGURE 7.

Cellular and systems phenotypes of Dravet syndrome (DS) in mice. A: electroencephalogram of a generalized tonic-clonic seizure in a DS mouse. B: loss of firing in interneurons. APs, action potentials; pA, picoamperes of stimulating current. Left: parvalbumin-expressing interneurons in layer V of the cerebral cortex. Black, wild type; blue, DS. Right, somatostatin-expressing interneurons in layer V of the cerebral cortex. Black, wild type (WT); gold, DS. Adapted from Ref. 151 with permission from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. C: thermal induction of seizures. P, postnatal day. D: autistic-like social interaction behavior. E, empty; C, center; M, mouse. E: context-dependent fear conditioning. #P < 0.05. Adapted from Ref. 152 with permission from Nature.

Studies of local synaptic circuits are also consistent with this phenotype. Recordings of spontaneous, action potential-driven excitatory postsynaptic currents and inhibitory postsynaptic currents in the CA1 neurons in hippocampal slices showed that the frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents was decreased (152, 158). In response to that decrease, the frequency of excitatory postsynaptic currents was increased, and the hippocampal network became hyperexcitable (152, 158, 159). In recordings of hippocampal circuit function in vivo, the frequency of occurrence of sharp waves and sharp-wave ripples was reduced, and the frequency of individual ripples within a single sharp-wave ripple was also significantly reduced (160). These findings are consistent with impairment of action potential firing by parvalbumin-sensitive inhibitory basket cells in the hippocampus, whose firing provides critical timing information for sharp-wave ripples (161). Thus, action potential firing in interneurons is impaired, the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory synaptic activity in neural circuits is consistently increased, and the timing of circuit function is altered in the hippocampus in the early stages of Dravet syndrome in mice. Moreover, the hippocampus is directly implicated in the generation of seizures (159), and selective heterozygous deletion of NaV1.1 in the hippocampus is sufficient to cause thermal seizures and cognitive deficit characteristic of Dravet syndrome (162).

In the cerebral cortex, disynaptic inhibition between neighboring pyramidal neurons in layer V, which is mediated by somatostatin-positive frequency-accommodating interneurons (163), was strikingly impaired in Dravet syndrome (DS) mice (151). In brain slices of cerebral cortex ex vivo, the excitability of parvalbumin-positive and somatostatin-positive interneurons was reduced in DS mice, and optogenetic silencing of those neurons led to circuit hyperexcitability (155). However, studies of network function in vivo did not reveal consistent changes in the cerebral cortex, suggesting that compensatory mechanisms may be engaged in the in vivo experimental setting (155). Of note, dysfunctions might be more visible when the circuit is challenged and involved in high-frequency activity, as observed in the hippocampus (159).

3.1.2. Febrile seizures in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome.

Dravet syndrome usually begins with febrile seizures during a fever, a hot day, or a hot bath (143, 164). This characteristic of Dravet syndrome is mimicked in genetically modified mice by thermally induced seizures (165). Slow increase in the core body temperature of DS mice into the fever range of 38–41°C generates myoclonic seizures followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures (FIGURE 7C). As in children with Dravet syndrome, susceptibility to thermally induced seizures is age dependent, with onset at a similar developmental time near the age of weaning, followed by more severe seizures and premature death (FIGURE 7C; Refs. 143, 165, 166).

3.1.3. Genetic evidence for a primary role of interneurons in Dravet syndrome.

Genetic evidence for a primary role of inhibitory interneurons in Dravet syndrome has come from specific gene deletion with the Cre-Lox method (167, 168). Deletion in forebrain interneurons using the Dlx promoter/enhancer, which is specifically expressed in developing GABAergic interneurons that arise in the medial ganglionic eminence and migrate to cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and other forebrain structures (169), recapitulates the thermally induced seizures, spontaneous seizures, and premature death of mice observed with global deletion of NaV1.1 channels (167). In contrast, specific deletion of NaV1.1 in excitatory neurons ameliorates the phenotypes of Dravet syndrome (168). These results clearly demonstrate that the primary cause of the core symptoms of Dravet syndrome is failure of normal action potential firing by GABAergic interneurons. Consistently, single-cell transcriptomic data from humans and mice have confirmed that SCN1A is predominantly expressed in inhibitory neurons (170), and transcranial magnetic stimulation paradigms applied to Dravet syndrome patients have disclosed reduced intracortical inhibition in vivo (171).

3.1.4. Comorbidities in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome.

The major comorbidities of Dravet syndrome are also caused by failure of firing of GABAergic interneurons (172). 1) Ataxia is correlated with failure of action potential firing of the GABAergic Purkinje neurons of the cerebellum, which are crucial for coordination of movement (157). 2) Cognitive deficit in context-dependent fear conditioning (FIGURE 7E) and spatial learning and autistic-like behaviors in social interaction tests (FIGURE 7D) are all observed in mice in which NaV1.1 channels have been specifically deleted in forebrain inhibitory interneurons (152, 173). 3) Impaired sleep quality is also observed in mice with specific deletion of NaV1.1 channels in forebrain interneurons, and it is correlated with failure of firing of the GABAergic interneurons of the reticular nucleus of the thalamus, which set sleep rhythms by driving sleep spindles (156). Failure of firing of these neurons has also been observed in different epileptic Scn1a models (158); however, one study puzzlingly reported hyperexcitability of these neurons in brain slices from Scn1aR1407X/+ mice (174). 4) The circadian rhythm defect is also correlated with failure of firing of the GABAergic neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, and it is rescued by enhancement of GABAergic neurotransmission with the benzodiazepine clonazepam, implicating failure of firing of interneurons as the primary cause of this defect (175). Thus, Dravet syndrome is an interneuronopathy in which an increase in excitation:inhibition balance in neural circuits throughout the brain causes the multifaceted comorbid disease phenotypes.

The Cre-Lox method has also been used to probe the functional roles of different classes of interneurons in the multifaceted phenotypes of Dravet syndrome (TABLE 1; Ref. 176). Nearly all of the interneurons in the cerebral cortex can be divided into three classes identified by their expression of parvalbumin, somatostatin, or the 5-HT3a receptor (177, 178). Heterozygous deletion of NaV1.1 channels in parvalbumin-expressing interneurons causes proepileptic effects and autistic-like behavior (176). Deletion in somatostatin-expressing interneurons causes proepileptic effects and hyperactivity (176). Deletion in these two classes of interneurons together gives synergistic effects on epilepsy, premature death, and cognitive deficit (176). In contrast, deletion in 5-HT3a receptor-expressing interneurons has much milder effects (TABLE 1; Ref. 179). It has been suggested that 5-HT3a receptor-expressing interneurons do not express NaV1.1 (180). However, single-cell RNA sequencing investigations suggest expression of NaV1.1 in these neurons (181, 182), and recent studies have shown reduced excitability of a subset of 5-HT3a receptor-expressing interneurons [irregular spiking vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)-positive interneurons] in layer II–III of the primary somatosensory and visual cortex (179, 183). Altogether, these studies indicate that altered excitation:inhibition balance in brain circuits, induced mainly by failure of action potential firing by parvalbumin-expressing interneurons, somatostatin-expressing interneurons, or both, induces both the core symptoms and the comorbidities of Dravet syndrome.

Table 1.

Functional impacts of deletion of NaV1.1 channels in specific classes of interneurons

| Interneuron | Epilepsy | SUDEP | Hyperactivity | Autistic Behavior | Cognitive Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | ++ | +/− | − | + | − |

| SST | + | − | + | − | − |

| PV + SST | +++ | ++ | + | + | + |

| 5-HT3R | − | − | − | +/− | − |

| All: Dlx-Cre | ++++ | ++++ | + | + | ++ |

PV, parvalbumin; SST, somatostatin; SUDEP, sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; 5-HT3R, 5-HT3 receptor.

3.1.5. SUDEP in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome.

SUDEP is the most serious result of Dravet syndrome, and parents and caregivers live in fear of this devastating outcome (144, 184, 185). In C57BL/6J mice, Dravet syndrome mutations cause a wave of high incidence of SUDEP on postnatal day (P)21–P28 (42, 154, 186). Specific deletion of NaV1.1 channels in forebrain interneurons is sufficient to cause the primary wave of SUDEP during P21–P28, indicating that epilepsy itself causes premature death at this time rather than other parallel effects of deletion of NaV1.1 channels in heart or other peripheral tissues (186). Consistent with this conclusion, specific heterozygous deletion in the heart does not cause SUDEP (186). SUDEP in DS mice is correlated with dramatic bradycardia (186), respiratory disturbances (187), and sudden cardiac arrest following generalized tonic-clonic seizures (186). Sudden death is prevented by peripheral administration of N-methylscopolamine, a peripherally restricted inhibitor of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (186). These results point to overactive parasympathetic cholinergic outflow from the central nervous system (CNS) during and after generalized tonic-clonic seizures, resulting in hyperactivation of cardiac muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, as the primary mechanism underlying SUDEP during P21–P28 in this model of Dravet syndrome (186). Abnormal parasympathetic regulation may disturb both respiration and cardiac function; however, prevention of sudden death by treatment with the non-CNS-penetrant muscarinic antagonist N-methylscopolamine administered in the peripheral circulation supports the conclusion that hyperactivation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the heart, resulting in severe bradycardia and ventricular arrhythmia, is the proximate cause of death in the Dravet syndrome model in C57BL/6J mice during P21–P28 (186).

3.1.6. Genetic background effects in Dravet syndrome.

Genetic background effects are important in Dravet syndrome. Complete loss-of-function truncation mutations cause differing degrees of disease severity in Dravet syndrome patients with different genetic backgrounds (143), and dramatic genetic background effects are observed for identical mutations in different strains of mice (42, 188). In the first study of Dravet syndrome in mice, the C57BL/6J strain was found to be much more susceptible to the disease mutation compared with the 129SvJ strain (42). For that reason, most subsequent studies have been carried out on mice bred for >10 generations into C57BL/6J. In this genetic background, Dravet syndrome mice recapitulate all of the complex symptoms and comorbidities of the human disease, as reviewed above. Physiological studies comparing Dravet syndrome mice in the C57BL/6 genetic background and the 129SvJ genetic background revealed less severely impaired action potential firing and less severely impaired sodium channel-dependent boosting of excitatory postsynaptic currents recorded in GABAergic inhibitory neurons in 129SvJ mice (188). These milder effects of the DS mutation on action potential firing in 129SvJ mice may contribute to the milder phenotype of DS in these mice. Gene mapping has identified a subunit of GABAA receptors as a contributing molecular factor to this difference in disease severity, again pointing to defects in inhibitory neurotransmission as fundamental in Dravet syndrome (189).

Dravet syndrome has also been studied in Scn1a+/− mice of mixed genetic backgrounds generated by crossing C57BL/6J with 129S6.SvEvTac (190, 191). The resulting 50:50 F1 generation mice have a milder epileptic phenotype than pure-bred C57BL/6J, and they require temperatures in the range of 42.5°C for thermal induction of seizures (190). This temperature range is characteristic of heat stroke, so the seizures induced at that temperature may not be epileptic in origin. These mice have not been analyzed for comorbidities of Dravet syndrome to date. Thus, at this stage, they are a less complete model for studies of Dravet syndrome than pure-bred C57BL/6J.

3.1.7. Compensatory effects in Dravet syndrome.

In addition to SCN1A, three other sodium channel genes are broadly expressed in the brain (133), but they do not effectively compensate for loss of NaV1.1 channels in Dravet syndrome. Early studies revealed increased expression of NaV1.3 channels in the hippocampus (42) and increased activity of NaV1.6 channels in the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum (157), but neither of these compensatory changes is sufficient to prevent the symptoms of Dravet syndrome (42, 157). In mice with mixed 50:50 C57BL/6J:129S6.SvEvTac genetic background, upregulation of sodium current was observed in dissociated hippocampal pyramidal neurons from P21 mice (191). Increased sodium channel activity at P21 may be important for generation of the first spontaneous seizures, which occur at this age in Dravet syndrome mice. In parvalbumin-expressing layer II–III interneurons in brain slices from the primary somatosensory cortex of these mixed-breed mice, action potential firing was diminished at P18–P21 but returned to normal at P35–P56 (192). These results open the possibility that normalization of action potential firing in these neurons takes place with increasing age, which would correspond to late childhood and early teenage years in humans, when seizures in Dravet syndrome become less severe and are more effectively treated with antiepileptic drugs (144). However, the reduction of sodium current and the impairment of action potential firing in cortical neurons is less prominent than in hippocampal neurons in C57BL/6 mice (42, 151, 155, 159). Therefore, it will be important to determine whether the excitability of these highly sensitive hippocampal neurons, as well as of cortical interneurons of other layers and cortical regions, also returns toward wild type in older mice or remains low and continues to create hyperexcitability in neuronal circuits in the adult.

3.1.8. Antiepileptic therapies tested in animal models of Dravet syndrome.

Mouse models of Dravet syndrome have been used to test both pharmacological treatments and gene therapy approaches. The first studies tested the effect of drugs and treatments already used in the clinic on seizures induced with hyperthermia or the convulsant flurothyl. The ketogenic diet (a high-fat/low-carbohydrate and protein diet used as an alternative treatment for refractory epilepsy) was effective in reducing the sensitivity to flurothyl-induced seizures (193). Stiripentol (an antiepileptic approved specifically for Dravet syndrome) and combinatorial therapy with stiripentol plus clobazam (a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors) were effective in reducing convulsant-induced seizures (194). Moreover, clonazepam (a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors) and tiagabine (a presynaptic GABA reuptake inhibitor) were effective individually in increasing the threshold for thermal induction of seizures and had synergistic beneficial effects when given together (195). Overall, these results established the Dravet syndrome mouse model as a potentially valuable asset in testing new drugs and drug combinations in Dravet syndrome.

More recent studies have tested drugs that are not yet used extensively in the clinic. The synthetic neuroactive steroid SGE-516 is a potent positive allosteric modulator of both synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. It increased threshold for hyperthermia-induced seizures, decreased frequency of spontaneous convulsive seizures, and prolonged survivals (196), consistent with other GABAA receptor-enhancing treatments. GS967, a nonconventional sodium channel blocker that preferentially inhibits persistent sodium current, was unexpectedly effective in reducing frequency of spontaneous seizures and mortality (197). The effect was probably related to a reduction of the excitability of excitatory neurons, which was enhanced in chronic administration because it reduced expression of NaV1.6 channels. A recent study reported reduction of seizures with chronic administrations of the peptidic toxin Hm1a, which can act as a specific NaV1.1 enhancer at nanomolar concentrations (198). However, delivery and dosage in clinical settings are challenging problems for this approach, in particular considering that at slightly higher concentrations Hm1a can hit numerous other targets (199).

Cannabidiol (CBD), a nonpsychotropic cannabinoid extracted from Cannabis sativa, is increasingly used to treat refractory epilepsy, and a small clinical trial showed a beneficial effect on Dravet syndrome patients (200). Clinical trials in Dravet syndrome are challenging because of the small number of patients, the wide age range of patients, and the differences in background standard-of-care medications that they receive concomitantly. Nevertheless, consistent with these clinical trial results, treatment with CBD reduced the duration and severity of hyperthermia-induced seizures and the frequency of spontaneous convulsive seizures of Scn1a+/− mice under carefully controlled laboratory conditions without other drugs (201), further supporting its therapeutic efficacy. When tested in brain slices in vitro, CBD increased inhibitory neurotransmission and decreased excitatory neurotransmission in the granule cell neurons of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, as measured by the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic currents. These effects were caused by direct increase of the frequency of action potentials in GABAergic neurons and a resulting decrease in dentate granule cell neurons. This latter effect may be due in part to the reduction of persistent current generated by NaV1.6 channels, which can be inhibited by CBD in transfected nonneuronal cells expressing NaV1.6 (202, 203). CBD binds in the pore of an ancestral bacterial sodium channel, providing a molecular mechanism for this inhibitory effect (204). Notably, CBD’s actions on mouse dentate granule cells from Scn1a+/− mice did not depend on activation of CB1 cannabinoid receptor but were potentially mediated by antagonism of the lipid-activated G protein-coupled receptor GPR55 (201).

Surprisingly, Scn1Lab−/− mutant zebrafish have provided a model of Dravet syndrome that can be efficiently used in drug screens (205, 206). These screens have identified serotoninergic drugs that in some cases were effective when tested in Dravet syndrome patients, and more detailed studies identified 5-HT2B receptors as the potential drug target (207, 208). Clinical trials are in progress to test the efficacy of previously developed drugs that target serotonin receptors for prevention of seizures in Dravet syndrome (https://www.epygenix.com/pipelines/). Although the motor dysfunction induced in zebrafish by Scn1a mutations is not similar to seizures in mammalian brain and the concentrations of drug candidates used in this system are much higher than typical for human pharmacology, the successes to date indicate that phenotypic screens in this novel experimental system have promise for discovery of unexpected classes of drug candidates for treatment of intractable epilepsy.

Gene therapy approaches have been recently developed for upregulating the wild-type Scn1a allele in Scn1a+/− mice. One study identified a novel antisense noncoding RNA (SCN1ANAT) implicated in a physiological mechanism that downregulates the expression of Scn1a (209). Antisense oligonucleotides (AntagoNATs) targeting and degrading SCN1ANAT were able to specifically upregulate Scn1a expression in vitro and in vivo after intrathecal administration in the brain of a Dravet syndrome mouse model and a wild-type nonhuman primate (209). Four weekly injections of AntagoNATs decreased frequency of spontaneous convulsive seizures and increased the threshold for hyperthermic seizures. Moreover, the treatment partially rescued the excitability of parvalbumin-positive hippocampal GABAergic neurons. A more recent study used antisense oligonucleotides targeted to Scn8a for reducing expression of NaV1.6,, which is the primary sodium channel driving firing of excitatory neurons. A single treatment of Dravet syndrome mice with Scn8a antisense oligonucleotides at P2 reduced spontaneous convulsive seizures and delayed mortality onset from 3 wk to beyond 5 mo of age (210), a surprisingly long-lasting beneficial effect that is consistent with the therapeutic benefits obtained by heterozygous gene deletion of NaV1.6 in another study (211). An additional approach used the CRISPR-ON system with a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) to upregulate Scn1a expression (212). A specific single guide RNA (sgRNA) that increases Scn1a gene expression levels in cell lines and primary neurons with high specificity was identified. Treatment with this CRISPR-ON strategy was able to increase NaV1.1 protein levels and rescue excitability of GABAergic neurons from Scn1a+/− mice in primary culture. Delivery of the Scn1a-dCas9 activation system to Scn1a+/− neonates (before disease onset) using adeno-associated viruses enhanced excitability of parvalbumin-positive interneurons in brain slices and increased threshold for thermally induced seizures (212). Most recently, Han et al. (213) used a targeted augmentation of nuclear gene output (TANGO) approach to increase the expression of functional NaV1.1 channels in Dravet syndrome mice. They observed a substantial decrease in spontaneous seizures and SUDEP when the specific antisense oligonucleotides were injected in newborn mice. These methods hold great promise for treatment of Dravet syndrome in children who can be identified by gene sequencing early in life before their symptoms arise. Altogether, these genetic approaches have a high level of specificity for NaV1.1 channels and reverse the effects of loss of function of this channel, but the timing of treatment, method of delivery, and half-life of therapeutic agents are still challenging problems that need to be solved.

3.2. Genetic Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus

The first pathogenic NaV1.1 mutations were identified in genetic epilepsy with febrile seizure plus (GEFS+) (214), which is characterized by a large phenotypic spectrum. Disease onset is between 3 mo and 6 yr, with febrile/hyperthermic seizures that continue to occur into adulthood. Spontaneous afebrile seizures develop later, and the most severe phenotypes in the GEFS+ spectrum are similar to Dravet syndrome (215). GEFS+ is genetically heterogeneous. Mutations are often identified in large families with autosomal dominant segregation and incomplete penetrance. Mutations of NaV1.1 have been identified in ∼20% of GEFS+ families, and they are all missense mutations.

GEFS+ NaV1.1 mutations were also the first to be functionally investigated in vitro (216). For this study, the cDNA of the long human splice variant was used, and the observed effect on NaV1.1 current was reduction of inactivation leading to increased persistent sodium current. This gain-of-function effect would be consistent with enhanced neuronal excitability, but that was opposite to the predicted effect of truncating DS mutations that had been previously identified (147). However, the same group reported loss of function for other GEFS+ mutations, in some causing complete loss of function, as for a DS missense mutation that was studied in parallel (217). Although a net gain-of-function effect was reported for a few other GEFS+ mutations in early work, studies performed thereafter have consistently shown that the general functional effect identified in transfected cells of both DS and GEFS+ NaV1.1 mutations is loss of function (153). The initial variability of functional effects was probably generated by the smaller functional effect of GEFS+ mutations compared to Dravet syndrome mutations, and by the experimental conditions used for the functional studies; in particular, the cellular background and the type of cDNA (including the specific splice variants) can have an important modulatory effect. Notably, the R1648H NaV1.1 GEFS+ mutation, which has been reported as a gain of function in an investigation that used heterologous expression systems (216), has been expressed in transgenic mice, and its functional effects have been studied in dissociated neocortical neurons (218). This study showed that in a neuronal cell background it induces loss of function but with modifications that are neuron subtype specific: slower recovery from inactivation and increased use-dependent inactivation in bipolar GABAergic interneurons but negative shift of voltage dependence of inactivation in pyramidal neurons.

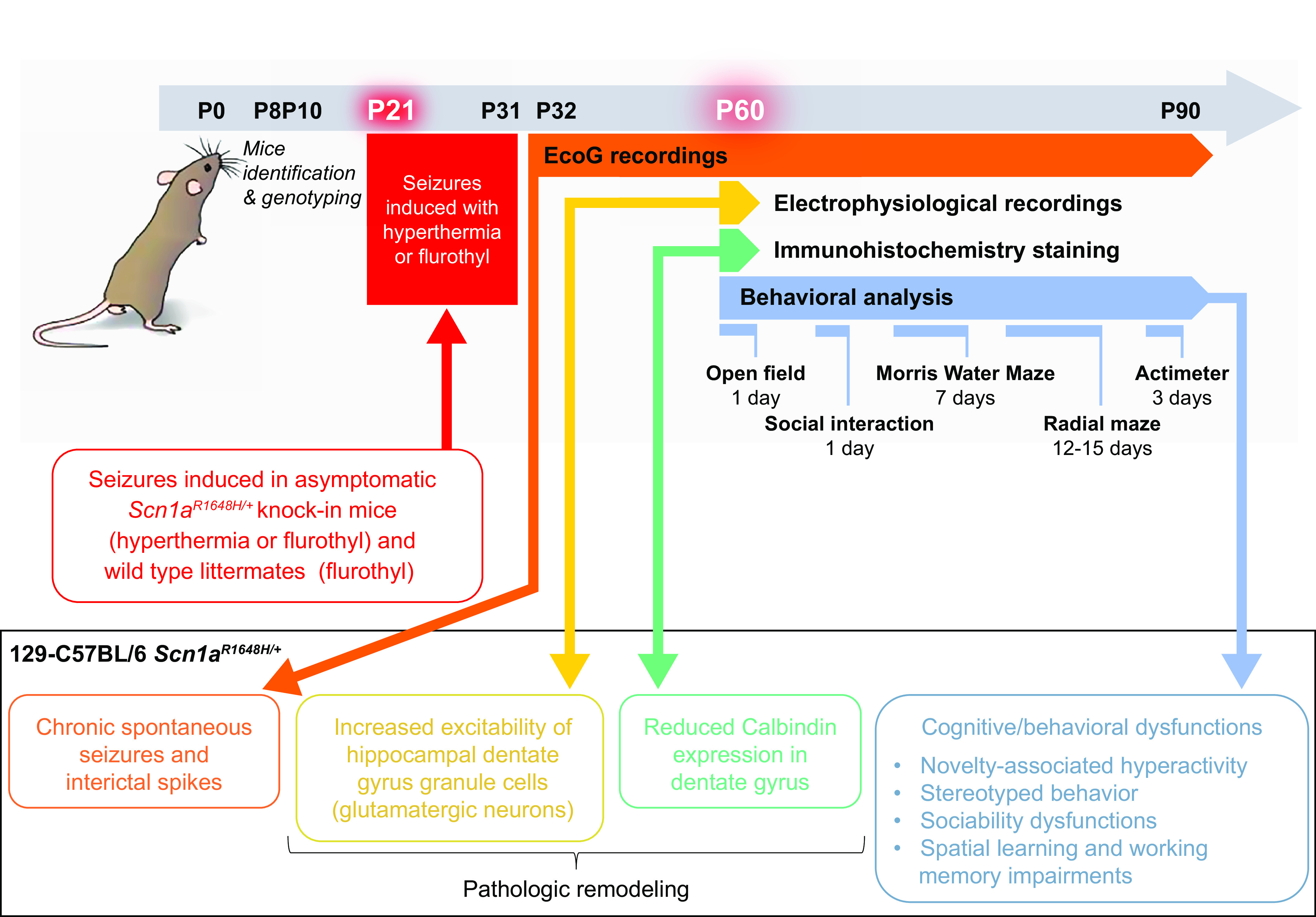

Clinical phenotypes observed in patients carrying the R1648H mutation show large variability, ranging from mild GEFS+ to severity approaching that of Dravet syndrome (214, 219). A gene-targeted knockin mouse model of the R1648H mutation was subsequently generated (Scn1aR1648H/+) to correlate neuronal dysfunctions with phenotypic features (219). In the first studies, it was reported that the phenotype of this model is characterized by hyperthermic and spontaneous seizures (219) and sleep dysfunctions (220), which were milder in comparison with mice carrying truncating mutations that model Dravet syndrome.

Experiments performed in brain slices obtained from Scn1aR1648H/+ mice (158) have shown hypoexcitability of GABAergic interneurons in cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus, as quantified by the reduced number of action potentials in input-output relationships, without detectable modifications in excitatory neurons. Reduced posthyperpolarization firing in GABAergic neurons of the reticular nucleus of the thalamus was also observed (158), as reported in global-knockout Scn1a+/− mice (156). Hypoexcitability of GABAergic neurons caused a reduction in action potential-induced postsynaptic GABAergic currents and tonic GABAergic current, as well as abnormal thalamo-cortical and hippocampal spontaneous network activities, which showed pathological high-frequency oscillations that were not observed in control. Thus, the basic pathological mechanisms observed in Scn1aR1648H/+ mice are similar to those observed in models of Dravet syndrome truncating mutations, supporting the conclusion that loss of function is responsible for the range of GEFS+ phenotypes of this mutation. However, the observed phenotype is milder, recapitulating the mildest phenotypes in the GEFS+ spectrum rather than the more severe phenotype approaching that of Dravet syndrome observed in some R1648H patients. The spectrum of phenotypes observed in these patients is consistent with the hypothesis that loss-of-function mutations in SCN1A cause a range of phenotypes, of which Dravet syndrome is the most severe (140).