Abstract

A total of 1,500 recent throat isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes collected between 1996 and 1999 from children throughout France were tested for their susceptibility to erythromycin, azithromycin, josamycin, clindamycin, and streptogramin B. The erythromycin-resistant isolates were further studied for their genetic mechanism of resistance, by means of PCR. The clonality of these strains was also investigated by means of serotyping and ribotyping. In all, 6.2% of the strains were erythromycin resistant, and 3.4 and 2.8% expressed the constitutive MLSB and M resistance phenotypes and harbored the ermB and mefA genes, respectively; ermTR was recovered from one isolate which also harbored the ermB gene. Ten serotypes and 8 ribotypes were identified, but we identified 17 strains by combining serotyping with ribotyping. Among the eight ribotypes, the mefA gene was recovered from six clusters, one being predominant, while the ermB gene was recovered from four clusters, of which two were predominant.

Penicillin is the drug of choice for the treatment of Streptococcus pyogenes infection. However, for patients sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics, and when these drugs fail, macrolides are often the recommended substitute. Penicillin resistance has not yet been described in S. pyogenes, but resistance to erythromycin and related antibiotics has been widely reported (2, 3, 5, 8, 10, 11, 17, 20, 29, 33, 43, 46). The mechanism of acquired resistance to erythromycin involves a target site modification mediated by a methylase which modifies the 50S ribosomal subunit, leading to the MLSB resistance phenotype encoded by erm genes (25, 36, 47). Erythromycin resistance due to an efflux mechanism (M phenotype), encoded by mef genes, has recently been described (6, 45). While the prevalence of the S. pyogenes resistance to macrolides has been reported worldwide, very few recent data deal with the French situation (1, 8). The aims of this study were to assess the macrolide sensitivity of recent throat isolates of S. pyogenes collected from French children, to determine the genetic mechanisms of resistance, and to explore clonality by means of serotyping and molecular methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 1,500 consecutive S. pyogenes isolates were collected between 1996 and 1999 throughout France. They were isolated by swabbing the throats of children, 4 to 17 years old (mean age, 11 years), with pharyngitis. The isolates were identified as S. pyogenes by colony morphology, beta-hemolysis on blood agar, and a commercial agglutination technique (Murex Diagnostics UK).

Susceptibility testing.

The procedures for susceptibility testing were those recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (30).

(i) Detection of erythromycin resistance and determination of resistance phenotypes.

Erythromycin-resistant strains were initially identified by the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% defibrinated horse blood (Diagnostic Pasteur, Marnes la Coquette, France) using 15-μg erythromycin disks (Diagnostic Pasteur) according to NCCLS guidelines (30). Simultaneously, the resistance phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates were determined by the double-disk test with erythromycin and clindamycin disks, as previously described (42). Blunting of the clindamycin inhibition zone proximal to the erythromycin disk indicated an inducible type of MLSB resistance, and resistance to both erythromycin and clindamycin indicated a constitutive type of MLSB resistance. Susceptibility to clindamycin with no blunting indicated the new erythromycin resistance phenotype (M phenotype).

(ii) Determination of MICs.

The MICs of erythromycin (Roussel Uclaf, Paris, France), azithromycin (Pfizer, Orsay, France), josamycin (Rhône-Poulenc-Rorer, Vitry-sur-Seine, France), clindamycin (Pharmacia Upjohn, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France), and streptogramin B (Rhône-Poulenc-Rorer) were determined for all the isolates that had an erythromycin inhibition zone diameter of less than 21 mm (30). MICs were determined by the agar dilution method with Mueller-Hinton medium supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood. The plates were incubated overnight at 35°C in ambient air. The NCCLS breakpoints for resistance (30) were as follows: susceptible (MIC ≤ 0.25 μg/ml) or resistant (MIC ≥ 1 μg/ml) to erythromycin and clindamycin and susceptible (MIC ≤ 0.5 μg/ml) or resistant to azithromycin (MIC ≥ 2 μg/ml). Given the lack of NCCLS recommendations on josamycin, we used the breakpoints recommended by the Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie (9), i.e., a susceptibility MIC of ≤1 μg/ml and a resistance of MIC ≥4 μg/ml.

Detection of erythromycin resistance genes.

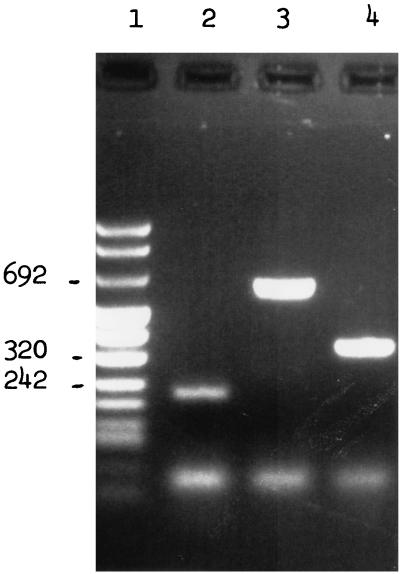

All erythromycin-resistant isolates were screened for erythromycin resistance genes. Isolates were grown in 20 ml of TGY broth (Diagnostic Pasteur) for 18 h. After centrifugation, bacterial DNA was prepared as previously described (4). The mef, erm, and ermTR genes were detected by PCR amplification, using previously published primers (24, 36). We used 5′-AGT ATC ATT AAT CAC TAG TGC-3′ and 5′-TTC TTC TGG TAC TAA AAG TGG-3′ to detect mefA, 5′-CGA GTG AAA AAG TAC TCA ACC-3′ and 5′-GGC GTG TTT CAT TGC TTG ATG-3′ to detect ermB, and 5′-GCA TGA CAT AAA CCT TCA-3′ and 5′-AGG TTA TAA TGA AAC AGA-3′ to detect ermTR. Amplification was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (no. 9600; Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) programmed for one cycle of denaturation at 95°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 55°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 10 min (24). Amplification products were run through 1% agarose gels. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and the DNA bands were visualized with a UV transilluminator. S. pyogenes 02C 1061, S. pyogenes 02 61110 and S. pyogenes 02C 1064 were used as positive PCR controls for the ermB, ermTR, and mefA genes, respectively (6, 7, 12, 44). Five erythromycin-susceptible S. pyogenes isolates were used as negative controls. Amplification of DNA from the positive controls with the corresponding primers produced PCR products of expected sizes (616, 348, and 206 bp for erm, mef, and ermTR, respectively) (Fig. 1). These PCR products were used for direct sequencing with an Applied Biosystems model 373 sequencer, using a modification of the method of Sanger et al. (35). The analysis showed that the amplimers were identical to mefA, ermB, and ermTR genes (6, 36, 47).

FIG. 1.

PCR analysis of the S. pyogenes erythromycin-resistant control strains using specific primers for detection of ermTR (lane 2), ermB (lane 3), and mefA (lane 4). Lane 1, DNA molecular weight marker.

After amplification, hybridization with DNA probes was performed for the mef and erm PCR products. The PCR products were transferred, by using a standard method, to Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham Bioproducts). The 616 and 348-bp PCR product from S. pyogenes 02C 1061 and 02C 1064, respectively, were chemiluminescence labeled according to the manufacturer's instructions and hybridized to the PCR products from each of the erythromycin-resistant isolates.

No hybridization was observed with the five erythromycin-susceptible control isolates.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the mef and erm PCR products.

The PCR products of the erythromycin resistance genes mef and erm from 15 randomly selected isolates were digested by MseI and Tsp509I (mefA) or FokI and SauIII (ermB), and electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide gel was performed as previously described (13). Gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and DNA bands were visualized with a UV transilluminator.

Serotyping.

Erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates were studied by T and M serotyping, and the presence of serum opacity factor was also determined as previously described (23), in the Colindale laboratory (Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom).

Genotyping.

Genotyping based on restriction fragment length polymorphism of the rRNA gene (ribotyping) was performed on all the erythromycin-resistant isolates. DNA was digested with HindIII and HhaI (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions and analyzed by Southern blotting with a chemiluminescent ribosomal probe, as previously described (4). Initial experiments on a few strains showed that HindIII produced a better distribution of restriction length fragments than did HhaI. HindIII was thus used to ribotype all the strains.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of and MICs for the S. pyogenes isolates with different erythromycin resistance phenotypes.

The screening plate method showed that 6.2% (93 of 1,500) of the S. pyogenes isolates had decreased susceptibility to erythromycin. Among those isolates, 3.4% (51 of 1,500) and 2.8% (42 of 1,500) expressed the constitutive MLSB and M resistance phenotypes, respectively. None of the isolates had the inducible MLSB resistance phenotype.

Table 1 shows the MICs for S. pyogenes according to the erythromycin resistance phenotype. All 93 strains were resistant to erythromycin (MIC breakpoint ≥1 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

MICs of macrolides and related agents against 93 erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates

| Erythromycin resistance genotype (nb) | Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 90% | Range | ||

| ermB (51)c | Erythromycin | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| Josamycin | >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Azithromycin | >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Clindamycin | >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Streptogramin B | 64 | 64 | 32–128 | |

| mefA (42) | Erythromycin | 8 | 8 | 4–16 |

| Josamycin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25–0.5 | |

| Azithromycin | 8 | 8 | 8–16 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064–0.125 | |

| Streptogramin B | 1 | 1 | 0.5–2 | |

50 and 90%, MIC50 and MIC90, respectively.

Number of isolates.

Including one strain harboring both ermB and ermTR.

Isolates with the MLSB phenotype were resistant to the 14-, 15- and 16-membered-ring macrolides (azithromycin and josamycin, respectively) and showed cross-resistance to clindamycin and streptogramin B. Isolates with the M phenotype were resistant to erythromycin and azithromycin, but the 16-membered-ring macrolides josamycin and clindamycin showed good activity against these isolates.

Erythromycin resistance genes of S. pyogenes isolates with different erythromycin resistance phenotypes.

PCR amplification followed by Southern hybridization showed that all the resistant isolates with the MLSB and M phenotypes harbored the ermB and mefA genes, respectively. Digestion of mef PCR products by MseI and Tsp5091 produced a single restriction pattern. We also observed a single restriction pattern when erm PCR products were digested by FokI and SauIII. PCR amplification with primers corresponding to ermTR identified only one isolate harboring this gene. Interestingly, this isolate also harbored the ermB gene.

Genotyping.

After digestion by HindIII, a total of 8 ribotypes (A to H) were observed among the 93 erythromycin-resistant isolates. Twenty-nine (31%), 20 (22%), 12 (13%), and 28 (30%) of the 93 erythromycin-resistant strains belonged to ribotypes A, G, E, and C, respectively. Four isolates (4%) had unique individual patterns. The ribotype distribution according to the genetic mechanism of resistance is reported in Table 2. The mefA gene was recovered from six clusters, with one being predominant, while the ermB gene was recovered from four clusters, with two being predominant.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of ribotypes according to the genetic mechanism of resistance

| Genetic mechanism of resistance (na) | No. of isolates with ribotyping profile

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

| ermB (51) | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 20 | 1 |

| mefA (42) | 29 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ermTR (1) | 1 | |||||||

Number of isolates.

Serotyping.

Serotyping identified 10 serotypes (Table 3). Thirty-two isolates (34%) were of serotype T4M4, 18 (19%) were of serotype T12M22, 12 (13%) were of serotype T12M12, 12 (13%) were of serotype T28R28, 5 (5%) were of serotype T2M2, 8 (9%) were of serotype T11M11, 3 (3%) were of serotype T1M1, and one each was of serotype T6M6, T22M22, and T13M77. No apparent geographic clustering of isolates of any serotype was observed.

TABLE 3.

Ribotypes of 93 erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates with various serotypes and genetic resistance mechanisms

| Serotype | n | Ribotypes

|

Genes

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | ermB | mefA | ermTR | ||

| T1M1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| T2M2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||

| T4M4 | 32 | 29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 31 | |||||

| T6M6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| T11M11 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |||||||||

| T12M12 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| T12M22 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |||||||||

| T22M22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| T13M77 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| T28R28 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 1 | ||||||||

The serum opacity factor typing was positive for all the isolates of serotypes T2M2, T4M4, T11M11, T12M22, and T28R28.

A strong correlation of some serotypes with particular erythromycin-resistance genotypes was found, as the gene mefA was present in all but one of the serotype T4M4 isolates and all the serotype T1M1 isolates. The ermB gene was found in all the isolates of serotypes T11M11, T12M22, and T28R28 and in all but one of the serotype T2M2 isolates.

The number of ribotypes within each serotype varied between one and four. The combination of ribotyping and serotyping allowed us to identify 17 strains (Table 3). Seventy percent of macrolide resistance due to mefA was due to T4M4 ribotype A, and 60% of ermB resistance was found in two clones.

DISCUSSION

Although S. pyogenes is consistently susceptible to penicillin, resistance to macrolides, first described in the United Kingdom in 1958 (26) and in the United States in 1968 (34), has been reported worldwide. The incidence of S. pyogenes erythromycin resistance remains low in most parts of the world but recently reached 17% in Finland (23), 27 to 34% in Spain (2, 32, 33), and 30 to 35% in Italy (5, 11). In our study, the prevalence of erythromycin resistance in S. pyogenes isolates from French children was only 6.2%. Similar percentages (4 to 10%) have been reported in Germany (G. Cornaglia, P. Huovinen, and The European GAS Study Group, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. E-149, 1998), the United Kingdom (Cornaglia et al., 38th ICAAC), Portugal (Cornaglia et al., 38th ICAAC), Greece (46), Canada (K. Weiss, M. Laverdière, C. Restieri, N. Persico, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. E-153, p. 213, 1998), and the United States (samples collected throughout continental United States) (3). Our low percentage of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates contrasts with the high prevalence of macrolide resistance associated with penicillin resistance in French S. pneumoniae isolates.

Until recently, the only known mechanism of resistance to erythromycin was target modification mediated by methylase, a phenomenon encoded by erm genes. At least 12 classes of erm genes have been identified by nucleic acid hybridization analysis and nucleotide sequence comparison (25, 47; K. Weiss, C. Restieri, L. A. Galarneau, M. Gourdeau, P. Harvey, J. F. Paradis, J. de Azavedo, K. Salim, and D. Low, Program Abstr. 5th Int. Conf. Macrolides, Azalides, Streptogramins, Ketolides, Oxazolidinones, abstr. 7.23, 2000). The latest gene in that class is designated ermTR (36). An efflux mechanism of resistance encoded by the mefA gene has also been reported (6). The gene encodes a hydrophobic 44.2-kDa protein sharing homology with membrane-associated pump proteins (6). The ermB and mefA genes were harbored by 3.4 and 2.8% of our isolates, respectively, conferring the MLSB and M phenotypes. Contrary to a previous report, none of our strains harbored both the ermB and mefA genes (18). However, the isolate which carried ermTR also harbored ermB, as previously observed (E. Di Modugno, A. Felici, M. Guerrini, H. Mottl, P. Piccoli, and D. Sabatini, Program Abstr. 5th Int. Conf. Macrolides, Azalides, Streptogramins, Ketolides, Oxazolidinones, abstr. 7.14, 2000). The M phenotype was found to be predominant among erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates in Finland (23), Sweden (20), Spain (32), and some areas in Italy (5), while an equal distribution of the M and inducible MLSB phenotypes was reported in Greece (46). Genetic investigations were made in Finland and Spain and showed the predominance of the mefA gene (23, 32). In agreement with previous studies (22, 33), the ermB gene conferred coresistance to 14-, 15-, and 16-membered-ring macrolides and lincosamides (MICs at which 90% of the isolates tested are inhibited [MIC90s] exceeding 128 μg/ml for both drugs), and to streptogramin B (MIC90 = 64 μg/ml); the mefA gene conferred resistance only to 14- and 15-membered-ring macrolides (MIC90 = 8 μg/ml).

Previous reports have suggested that erythromycin resistance is often associated with specific serotypes (21). Indeed, the increase in erythromycin resistance among S. pyogenes isolates has been linked to the spread of serotype T12 in Japan (27, 28, 29) and serotype T4M4 in Finland (23). Eight T and 9 M agglutination patterns were observed in our study among the 93 erythromycin-resistant isolates.

Although serotyping has provided useful epidemiologic information, its discriminatory power is considered poor because of genetic heterogeneity among isolates of the same serotype on the one hand and the existence of the same genotype among different serotypes on the other hand. Genomic typing methods such as restriction endonuclease analysis (REA), random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis have been applied to S. pyogenes, together with ribotyping (15, 32, 40, 41). Ribotyping was found to be less discriminatory than REA (4). However, the complexity of the restriction patterns makes it difficult to analyze a large number of isolates by REA. We used ribotyping for strain differentiation, identifying eight ribotypes among the 93 erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates. We combined ribotyping and serotyping. In 3 out of 10 cases, ribotyping revealed genetic differences among isolates of the same serotype. Although ribotyping identified many different clones within a single serotype, identical ribotypes were detected among isolates of different serotypes. Analysis of the M protein sequences has shown that some serotypes are phylogenetically closer than others (14). Ribotyping adds to the discriminatory power of serotyping, especially when epidemiologically unrelated isolates are compared (41); we identified 17 different strains in this way.

Six of the eight ribotypes carried either the mefA or the ermB gene. The mefA gene was recovered from six clusters. One cluster was predominant, and most of the strains were serotype T4M4. In Finland, the increase in erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes with the M phenotype was also due to strains of serotype T4M4 (23). The ermB gene was recovered from four clusters, two being predominant. Thus, most isolates carrying the mefA gene were unrelated to those harboring the ermB gene. The location of erm and possibly mef on a chromosomal conjugative transposon may explain the spread of erythromycin resistance to different clones of S. pyogenes (25). The isolate harboring ermTR was of serotype M28T28. Interestingly, the resistance of S. pyogenes to macrolides in Quebec, Canada, is due to a single M28T28 clone possessing the ermTR gene (K. Weiss et al., 5th ICMASKO).

Macrolide resistance is closely related to the extent to which these agents are used, and national surveys have shown that decreases in macrolide use lead to decreases in the incidence of macrolide resistance (16, 37, 39). Moreover, a significant negative correlation has been found between the age of patients and the occurrence of erythromycin-resistant organisms (38). This seems to be the result of prescription of more antibiotics for children together with a greater risk of cross-colonization among children than among adults. The fact that the level of erythromycin resistance among our S. pyogenes isolates was below 7% may be related to the stable consumption of macrolides in France since 1980 (19, 31) and to the absence of clonal spread of erythromycin-resistant strains. The pharyngeal origin of all our isolates may also explain the relatively low incidence of erythromycin resistance, as a significantly higher rate of resistance is observed with invasive strains (43, 48). However, it has been suggested that strain virulence is not related to antimicrobial resistance (21).

In conclusion, we found a low level of erythromycin resistance in S. pyogenes in France. Moreover, as only 2.8% of the isolates had the M phenotype, clindamycin and josamycin would be the drugs of choice for treating children with clinical failure after phenoxymethyl penicillin, and for penicillin-allergic patients. Further careful surveillance of erythromycin resistance with other macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramin B is required to follow changes in S. pyogenes resistance patterns in France.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joyce Sutcliffe for providing S. pyogenes reference strains 02C 1064, 02C 1076, and 02 61110; R. Leclercq for helpful discussion; and Androulla Efstratiou for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arpin C, Canron M H, Noury P, Quentin C. Emergence of mefA and mefE genes in beta-hemolytic streptococci and pneumococci in France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:133–134. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baquero F, García-Rodríguez J A, García De Lomas J, Aguilar L The Spanish Surveillance Group for Respiratory Pathogens. Antimicrobial resistance of 914 beta-hemolytic streptococci isolated from pharyngeal swabs in Spain: results of a 1-year (1996–1997) multicenter surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:178–180. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Brown S D. Macrolide resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from out-patients in the USA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:139–140. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bingen E, Denamur E, Lambert-Zechovsky N, Boissinot C, Brahimi N, Aujard Y, Blot P, Elion J. Mother-to-infant vertical transmission and cross-colonization of Streptococcus pyogenes confirmed by DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:147–150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borzani M, De Luca M, Varotto F. A survey of susceptibility to erythromycin amongst Streptococcus pyogenes isolates in Italy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:457–458. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clancy J, Petipas J, Dib-Hajj F, Yuan W, Cronan M, Kamath A V, Bergeron J, Retsema J A. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of a novel macrolide-resistance determinant, mefA, from Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:867–879. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clewell D B, Franke A E. Characterization of a plasmid determining resistance to erythromycin, lincomycin, and vernamycin Bα in a strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1974;5:534–537. doi: 10.1128/aac.5.5.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen R, Fremaux A, de Gouvello A, Deforche V, Levy C, Wadbled D, de la Rocque F, Varon E, Geslin P. Sensibilitéin vitro de souches de Streptococcus pyogenes récemment isolées d'angines communautaires. Med Mal Infect. 1996;26:765–769. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie. Pathol Biol. 1998;46:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coonan K M, Kaplan E L. In vitro susceptibility of recent North American group A streptococcal isolates to eleven oral antibiotics. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:630–635. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199407000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornaglia G, Ligozzi M, Mazzariol A, Masala L, Lo Cascio G, Orefici G, Fontana R The Italian Surveillance Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Resistance of Streptococcus pyogenes to erythromycin and related antibiotics in Italy. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S87–S92. doi: 10.1086/514908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Azavedo J C S, Yeung R H, Bast D J, Duncan C L, Borgia S B, Low D E. Prevalence and mechanisms of macrolide resistance in clinical isolates of group A streptococci from Ontario, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2144–2147. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doit C, Denamur E, Picard B, Geslin P, Elion J, Bingen E. Mechanisms of the spread of penicillin in Streptococcus pneumoniae strains causing meningitis in children in France. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:520–528. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischetti V A. Streptococcal M protein: molecular design and biological behavior. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:285–314. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.3.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitoussi F, Cohen R, Brami G, Doit C, Brahimi N, de la Rocque F, Bingen E. Molecular DNA analysis for differentiation of persistence or relapse from recurrence in treatment failure of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:233–237. doi: 10.1007/BF01709587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujita K, Murono K, Yoshikawa M, Murai T. Decline of erythromycin resistance of group A streptococci in Japan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:1075–1078. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199412000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber M A. Antibiotic resistance: relationship to persistence of group A streptococci in the upper respiratory tract. Pediatrics. 1996;97(Suppl.):971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovanetti E, Montanari M P, Mingoia M, Varaldo P E. Phenotypes and genotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes strains in Italy and heterogeneity of inducibility-resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1935–1940. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillemot D, Maison P, Carbon C, Balkau B, Vauzelle-Kervroëdan F, Sermet C, Bouvenot G, Eschwège E. Trends in antimicrobial drug use in the community between 1981 and 1992, in France. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:492–497. doi: 10.1086/517384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jasir A, Schalén C. Survey of macrolide resistance phenotypes in Swedish clinical isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:135–137. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan E L. Recent evaluation of antimicrobial resistance in β-hemolytic streptococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl. 1):S89–S92. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kataja J, Huovinen P, Skurnik M, Seppala H The Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Erythromycin resistance genes in group A streptococci in Finland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:48–52. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kataja J, Huovinen P, Muotiala A, Vuopio-Varkila J, Efstratiou A, Hallas G, Seppälä H The Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Clonal spread of group A Streptococcus with the new type of erythromycin-resistance. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:786–789. doi: 10.1086/517809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klugman K P, Capper T, Widdowson C A, Koornhof H J, Moser W. Increased activity of 16-membered lactone ring macrolides against erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization of South African isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:729–734. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1267–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowbury E J L. Symposium on epidemiological risks of antibiotics. Hospital infections. Proc R Soc Med. 1958;51:807–810. doi: 10.1177/003591575805101006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maruyama S, Yoshioka H, Fujita K, Takimoto M, Satake Y. Sensitivity of group A streptococci to antibiotics. Am J Dis Child. 1979;133:1143–1145. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1979.02130110051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyamoto Y, Takizawa K, Matsushima A, Asai Y, Nakatsuka S. Stepwise acquisition of multiple drug resistance by beta-hemolytic streptococci and difference in pattern by type. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;13:399–404. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakae M, Murai T, Kaneko Y, Mitsuhashi S. Drug resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes isolated in Japan (1974–1977) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;12:427–428. doi: 10.1128/aac.12.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eighth informational supplement. M100 S8. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Observatoire national des prescriptions et consommations des médicaments dans les secteurs ambulatoire et hospitalier, and Agence du médicament, Direction des études et de l'information pharmaco-économiques. Prescription et consommation des antibiotiques en ambulatoire. Bull Soc Fr Microbiol. 1999;14:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Trallero E, Marimon J M, Montes J M, Orden B, de Pablos M. Clonal differences among erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;3:235–240. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez-Trallero E, Urbieta M, Montes M, Ayestaran I, Marimon J M. Emergence of Streptococcus pyogenes strains resistant to erythromycin in Gipuzkoa, Spain. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:25–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01584359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders E, Foster M T, Scott D. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci resistant to erythromycin and lincomycin. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:538–540. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196803072781005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seppäla H, Skurnik M, Soini H, Roberts M C, Huovinen P. A novel erythromycin resistance methylase gene (ermTR) in Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:257–262. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seppäla H, Klaukka T, Vuopio-Varkila J, Muotiala A, Helenus H, Lager K, Huovinen P the Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:441–446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708143370701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seppäla H, Klaukka T, Lehtonen R, Nenonen E, Huovinen P. Erythromycin resistance of group A streptococci from throat samples is related to age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:651–656. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199707000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seppäla H, Klaukka T, Lehtonen R, Nenonen E, Huovinen P the Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Outpatient use of erythromycin: link to increased erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1378–1385. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.6.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seppälä H, He Q, Österblad M, Huovinen P. Typing of group A Streptococci by random, amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1945–1948. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1945-1948.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seppälä H, Vuopio-Varkila J, Österblad M, Jahkola M, Rummukainen M, Holm S E, Huovinen P. Evaluation of methods for epidemiologic typing of group A streptococci. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:519–525. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seppäla H, Nissinen A, Yu Q, Huovinen P. Three different phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Finland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:885–891. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seppäla H, Nissinen A, Järvinen H, Huovinen S, Henriksson T, Herva E, Holm E, Jahkola M, Katila M-L, Klaukka T, Kontiainen S, Liimatainen O, Oinonen S, Passi-Metsomaa L, Huovinen P. Resistance to erythromycin in group A streptococci. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:292–297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutcliffe J, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes resistant to macrolides but sensitive to clindamycin: a common resistance pattern mediated by an efflux system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1817–1824. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tzelepi E, Kouppari G, Mavroidi A, Zaphiropoulou A, Tzouvelekis L S. Erythromycin resistance amongst group A β-haemolytic streptococci isolated in a paediatric hospital in Athens, Greece. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:745–746. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:577–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.York M K, Gibbs L, Perdreau-Remington F, Brooks G F. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from the San Francisco Bay area of Northern California. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1727–1731. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1727-1731.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]