Abstract

Previous experiments with rifalazil (RLZ) (also known as KRM-1648) in combination with isoniazid (INH) demonstrated its potential for short-course treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. In this study we investigated the minimum RLZ-INH treatment time required to eradicate M. tuberculosis in a murine model. RLZ-INH treatment for 6 weeks or longer led to a nonculturable state. Groups of mice treated in parallel were killed following an observation period to evaluate regrowth. RLZ-INH treatment for a minimum of 10 weeks was necessary to maintain a nonculturable state through the observation period. Pyrazinamide (PZA) was added to this regimen to determine whether the treatment duration could be further reduced. In this model, the addition of PZA did not shorten the duration of RLZ-INH treatment required to eradicate M. tuberculosis from mice. The addition of PZA reduced the number of mice in which regrowth occurred, although the reduction was not statistically significant.

The benzoxazinorifamycin derivative rifalazil (RLZ) (previously known as KRM-1648) has been shown to have superior in vitro and in vivo activities against Mycobacterium tuberculosis compared to that of rifampin (RIF) or rifabutin (6, 7, 13). Previous experiments in our laboratory in which we compared RIF, RLZ, and isoniazid (INH) treatment, alone or in combination (RIF-INH or RLZ-INH), for 12 weeks demonstrated that RLZ alone was the most active single agent, achieving a sterile (nonculturable) state by 12 weeks (8). RLZ-INH was superior to RIF-INH treatment in its ability to produce a nonculturable state earlier (6 versus 12 weeks, respectively) in the spleens and lungs of infected mice. The nonculturable state achieved after 12 weeks of RLZ-INH treatment was maintained for at least 6 months following the cessation of therapy. In contrast, regrowth of M. tuberculosis was detected 1 month following the cessation of RIF-INH therapy.

The purpose of the first study was to determine the shortest duration of RLZ-INH treatment required to achieve a sterile state. The study compared 6, 8, 10, or 12 weeks of RLZ-INH therapy. Mice treated in parallel were killed 4 months after the cessation of therapy to observe any regrowth.

Clinical trials performed in the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated the ability of pyrazinamide (PZA) to shorten the duration of therapy when it is given in combination with INH and RIF (1, 11, 12, 13). The addition of PZA to INH-RIF during the first 2 months of treatment led to a reduction in the duration of antituberculosis therapy from 9 to 6 months. In this report, PZA was added to the treatment regimen to determine whether the duration of RLZ-INH therapy could be reduced.

PZA was evaluated in two separate experiments. The first of these tested the effects that PZA had early in therapy. Mice that were given PZA in combination with RLZ-INH for either 3, 4, 5, or 6 weeks were compared to groups that received RLZ-INH alone. The second study compared RLZ-INH to RLZ-INH-PZA treatment for either 6, 8, or 10 weeks to determine the minimum treatment duration required to produce a nonculturable state. Groups treated in parallel were killed 3 months posttreatment to observe regrowth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs.

RLZ was provided by Kaneka Corporation, Osaka, Japan. The drug was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with subsequent dilution in distilled water. The final concentration of DMSO was 0.5% at the time of administration. INH and PZA (purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) were dissolved in distilled water. Drugs were prepared each morning prior to administration. The doses of RLZ, INH, and PZA were 20, 25, and 150 mg/kg of body weight, respectively.

Isolate.

M. tuberculosis ATCC 35801 (strain Erdman) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. The MICs of RLZ (0.00047 μg/ml) and INH (0.06 μg/ml) were determined in modified 7H10 broth (pH 6.6; 7H10 agar formulation with agar and malachite green omitted) supplemented with 10% Middlebrook oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) enrichment (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and 0.05% Tween 80. The MIC of PZA (32 μg/ml) was determined in the modified 7H10 broth described above, but at pH 5.8.

Media.

The organism was grown in modified 7H10 broth (pH 6.6) with 10% OADC enrichment and 0.05% Tween 80 for 5 days on a rotary shaker at 37°C. Cultures were diluted to 100 Klett units (5 × 107 CFU) per ml (Klett-Summerson colorimeter; Klett Manufacturing, Brooklyn, N.Y.) on the day of infection. The organism was titrated in triplicate on 7H10 agar plates (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 10% OADC enrichment to determine the inoculum size. The plates were incubated at 37°C in ambient air for 4 weeks prior to counting.

Infection studies.

These studies were performed in three separate experiments. Five- to 6-week-old female outbred CD-1 mice (Charles River, Wilmington, Ma.) were infected intravenously through a caudal vein. Each mouse received approximately 107 viable organisms suspended in 0.2 ml of modified 7H10 broth. There were eight mice per group.

Treatment was started 1 week postinfection and was given 5 days/week for a designated time period. Drugs were given orally by gavage in a dose volume of 0.2 ml. At the initiation of therapy mice in an early control group (untreated, infected mice) were killed. Mice in a second control group, designated the late control group, were killed 7 weeks postinfection. In the first experiment RLZ-INH was given for 6, 8, 10, or 12 weeks. Mice treated in parallel for 6, 8, 10, or 12 weeks were maintained for a 4-month observation period (no treatment). The second experiment consisted of RLZ-INH or RLZ-INH-PZA treatment for 3, 4, 5, or 6 weeks. For the third experiment RLZ-INH or RLZ-INH-PZA treatment was given for 6, 8, or 10 weeks. Groups treated in parallel were maintained for 3 months of observation.

Three to 5 days following completion of treatment or observation, the mice were killed by CO2 inhalation. Spleens and right lungs were aseptically removed and ground in a tissue homogenizer. For the treatment groups that received either regimen (with or without PZA), the entire volume of organ homogenate was plated (0.1-ml aliquots) to determine the number of culturable mycobacteria per organ. This method was used for all treatment and observation time points (except for the first experiment described, in which only observation groups that received RLZ-INH for 10 and 12 weeks were evaluated by this method). For all other groups the number of viable organisms was determined by titration on 7H10 agar plates. The plates were incubated in ambient air at 37°C for 4 weeks.

Statistical evaluation.

The viable cell counts for the control groups and the groups treated for less than 6 weeks were converted to logarithms, which were then evaluated by one- or two-variable analyses of variance. Statistically significant effects from the analyses of variance were further evaluated by Tukey honestly significant difference tests to make pairwise comparisons among the means. For groups of mice treated for 6 or more weeks with either treatment regimen (in which no colonies of M. tuberculosis were recovered from some mice), the statistical method used to compare the occurrence of mycobacterial growth was the Fisher exact test for two-by-two contingency (3).

RESULTS

Sterilizing activity of RLZ in combination with INH.

Mice were treated with RLZ-INH for 6, 8, 10, or 12 weeks to determine the minimum duration of treatment required to achieve a sterile state. Female CD-1 mice were infected with 5.2 × 107 viable mycobacteria. Groups of mice treated in parallel were maintained for 4 months posttreatment to observe regrowth. Control mice (infected, but untreated), designated early and late controls, were killed at the beginning and end of treatment (12 weeks), respectively.

The difference in cell counts between the early and late control groups was significant for spleens (P < 0.01) but not lungs (P > 0.05). Treatment with RLZ-INH for 6 weeks or greater significantly reduced the number of mice per group in which M. tuberculosis was detected in both spleens and lungs compared to the reductions for the early and late controls (P < 0.01) (Table 1). There was no significant difference in the reduction of M. tuberculosis detected in the spleens or lungs of mice between 6, 8, 10, or 12 weeks of treatment (P > 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Number of viable M. tuberculosis organisms recovered in spleens and lungs following 6, 8, 10, or 12 weeks of RLZ-INH treatmenta

| Duration (wk) | Mean ± SD log no. of CFU in spleens

|

Mean ± SD log no. of CFU in lungs

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlb | Treatment | Treatment + observationc | Control | Treatment | Treatment + observation | |

| 0d | 7.21 ± 0.22 (7/7)e | 5.99 ± 0.21 (7/7) | ||||

| 6 | 1.08 (1/7)f | 3.15 ± 0.56 (7/8) | 0.30 (1/7) | 2.68 ± 0.15 (4/8) | ||

| 8 | 0 (0/8) | 2.93 ± 0.53 (5/8) | 0.70 (1/8) | 2.54 (1/8) | ||

| 10 | 0 (0/8) | 0.22 ± 0.00 (2/8) | 0 (0/8) | 1.45 (1/8) | ||

| 12 | 4.48 ± 0.66 (5/5) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 5.99 ± 0.70 (5/5) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) |

Groups treated in parallel were maintained to observe regrowth. The mean log number of CFU was calculated for mice in which growth occurred.

One mouse in the 12-week control group died, while the data for the other mice could not be used due to technical error.

Four-month observation phase.

Week 0 represents the beginning of treatment (1 week postinfection).

The values in parentheses represent the number of mice per group (eight per group) in which viable M. tuberculosis was detected/total number of mice in the group.

One mouse died.

Regrowth of M. tuberculosis occurred after 4 months of observation in mice treated for 6, 8, and 10 weeks but not in mice treated for 12 weeks (Table 1) (the mean log number of CFU reported in Table 1 was calculated from data for mice that had growth). The number of mice per group in which regrowth was observed decreased with the length of therapy. Regrowth in the spleens was observed in seven of eight, five of eight, and two of eight mice following 6, 8, and 10 weeks of therapy, respectively. The number of mice in the 6-week treatment group in which regrowth occurred was not statistically different from the number of mice in the 8-week treatment group in which regrowth occurred (P > 0.05) but was significantly different from the number of mice in the 10- or 12-week treatment group in which regrowth occurred (P < 0.03). The difference in regrowth between groups treated for 10 or 12 weeks was not significant (P > 0.05).

For the lungs, regrowth was observed in four of eight, one of eight, and one of eight mice treated for 6, 8, and 10 weeks, respectively. The occurrence of regrowth following 6 weeks of treatment was not significantly different from the occurrence of regrowth following 8 or 10 weeks of treatment (P > 0.05), although there was a significant difference in the occurrence of regrowth between groups treated for 6 and 12 weeks (P < 0.04). There was no difference in the occurrence of regrowth between groups treated for 8, 10, or 12 weeks (P > 0.05).

Effects of PZA, given in addition to RLZ-INH, early in treatment.

In order to determine what effect the addition of PZA had on RLZ-INH treatment, mice were given either RLZ-INH or RLZ-INH-PZA for 3, 4, 5, or 6 weeks. Female CD-1 mice were infected with 5 × 106 viable mycobacteria. Mice designated early and late controls were killed at the beginning and end of drug administration (6 weeks), respectively.

The difference in cell counts between early controls and late control mice was significant for the spleens (P < 0.03) but not for the lungs (P > 0.05). Treatment with either drug combination for 3 weeks or greater significantly reduced the cell counts in the spleens and lungs compared to those in the early and late controls (P < 0.01).

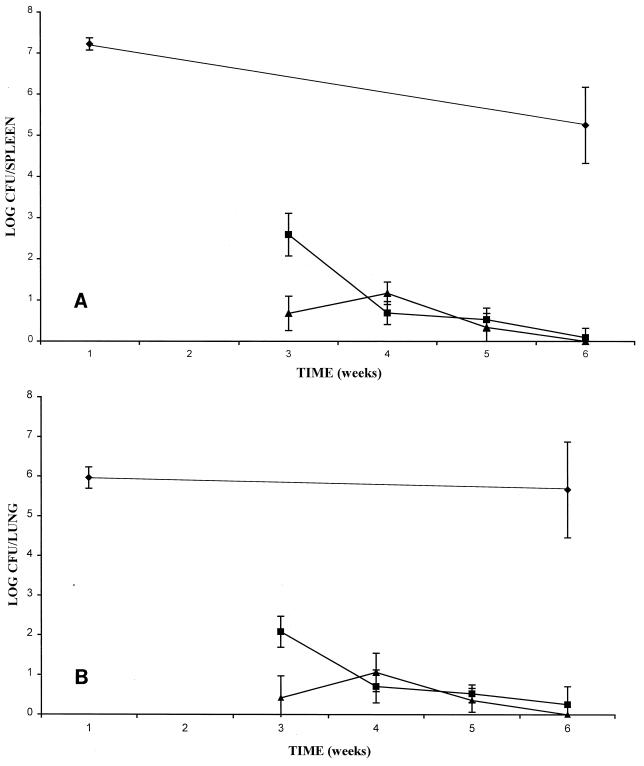

PZA was shown to have its greatest effect at the earliest treatment point. Mice given RLZ-INH-PZA for 3 weeks had a significantly greater reduction in cell counts compared to that for mice given RLZ-INH for 3 weeks for both spleens and lungs (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A and B, respectively). There was no difference in cell counts between mice given RLZ-INH-PZA and mice given RLZ-INH at any other time point (P > 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Mean number of CFU in spleens (A) and lungs (B) of mice treated with either RLZ-INH (■) or RLZ-INH-PZA (▴) for 3, 4, 5, or 6 weeks. (⧫), controls.

Effect of PZA on sterilizing activity of RLZ-INH.

In order to determine whether PZA may be able to shorten the duration of RLZ-INH therapy similar to that seen for RIF-INH for the treatment of clinical tuberculosis, mice were treated with either RLZ-INH-PZA or RLZ-INH for 6, 8, or 10 weeks. Female CD-1 mice were infected with 1.6 × 107 viable mycobacteria. Groups of mice treated in parallel were maintained for 3 months posttreatment to observe regrowth. Control mice, designated early and late controls, were killed at the initiation of treatment and 6 weeks later, respectively.

The difference in cell counts between early and late control mice was significant for both the spleens and lungs (P < 0.01). Treatment, with or without PZA, for 6 weeks or more significantly reduced the occurrence of mycobacterial growth compared to that in both early and late controls (P < 0.01) (Table 2). There was no significant difference between 6, 8, or 10 weeks of treatment with either RLZ-INH or RLZ-INH-PZA in terms of the occurrence of mycobacterial growth in the spleens or lungs of mice (P > 0.05). The addition of PZA did not significantly improve RLZ-INH therapy at any time point (P > 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Number of viable M. tuberculosis organisms recovered following 6, 8, or 10 weeks of RLZ-INH or RLZ-INH-PZA treatmenta

| Duration (wk) | Mean ± SD log no. of CFU in spleens

|

Mean ± SD log no. of CFU in lungs

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | RLZ-INH | RLZ-INH-PZA | Control | RLZ-INH | RLZ-INH-PZA | |

| 0b | 7.12 ± 0.27 (8/8)c | 6.45 ± 0.44 (8/8) | ||||

| 6 | 6.01 ± 0.81 (8/8) | 0.77 ± 0.40 (3/8) | 0.85 (1/8) | 7.19 ± 0.29 (8/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0.30 ± 0.00 (2/8) |

| 8 | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | ||

| 10 | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | ||

| 6 + obsd | 2.69 ± 0.87 (8/8) | 3.27 ± 0.12 (5/8) | 2.60 ± 0.49 (3/8) | 3.43 ± 0.00 (2/8) | ||

| 8 + obs | 3.31 ± 0.14 (5/8) | 2.08 ± 0.00 (3/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | ||

| 10 + obs | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | ||

Groups treated in parallel were maintained to observe regrowth. The mean log number of CFU was calculated for mice in which growth occurred.

Week 0 represents the beginning of treatment (1 week postinfection).

The values in parentheses represent the number of mice per group (eight per group) in which viable M. tuberculosis was detected/total number of mice in the group.

Three-month observation (obs) phase.

Regrowth of M. tuberculosis was observed in the spleens of mice that received either treatment regimen for 6 or 8 weeks. Regrowth was observed in the lungs of mice given either treatment regimen for 6 weeks (Table 2) (the mean log number of CFU reported in Table 2 was calculated from data for mice that had growth). For mice that received RLZ-INH therapy for 6 and 8 weeks, regrowth was observed in the spleens of eight of eight and five of eight mice, respectively. In the lungs, regrowth occurred in three of eight mice following 6 weeks of therapy. Five of eight and three of eight mice that received RLZ-INH-PZA, for 6 and 8 weeks, respectively, had regrowth in the spleens following the 3-month observation phase. Regrowth in the lungs occurred in two of eight mice following 6 weeks of therapy.

The occurrence of regrowth in the spleens after treatment with RLZ-INH for 6 weeks was not significantly different from that seen after treatment for 8 weeks (P > 0.05), but it was significantly different from that seen after treatment for 10 weeks (P < 0.01). The difference in regrowth between 8 and 10 weeks of treatment was significant (P < 0.01).

The occurrence of regrowth in the lungs of mice that received RLZ-INH for 6 weeks was not statistically different from that seen in mice that received treatment for 8 and 10 weeks (P > 0.05). The difference in regrowth between mice that received therapy for 8 and 10 weeks was not significant (P > 0.05). The mean log number of CFU in mice that received RLZ-INH (three of eight mice) for 6 weeks was 2.60 ± 0.49. Eight weeks of treatment with RLZ-INH was required to completely eradicate the mycobacteria from the lungs of infected mice.

The occurrence of regrowth in the spleens of mice that received RLZ-INH-PZA for 6 weeks was not statistically different from that seen in mice that received therapy for 8 weeks (P > 0.05) but was significantly different from that in mice that received therapy for 10 weeks (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in regrowth observed between mice that received treatment for 8 and 10 weeks (P > 0.05). There was no statistical difference in regrowth of mycobacteria in the lungs of mice that received RLZ-INH-PZA for 6, 8, or 10 weeks (P > 0.05).

The addition of PZA to RLZ-INH consistently reduced the level of regrowth observed at the conclusion of the observation phase in groups treated for 6 and 8 weeks (in the spleens, eight of eight and five of eight mice for RLZ-INH versus five of eight and three of eight mice for RLZ-INH-PZA, respectively). However, the differences between treatment regimens at any time point were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Recently, therapy against M. tuberculosis infection has been complicated by the presence of drug-resistant strains. One major factor that contributes to the development of drug resistance is poor patient compliance (9). Two approaches that may encourage better compliance are lengthening the time between doses (intermittent chemotherapy), e.g., once-weekly therapy, and shortening the overall treatment period (4).

Two new rifamycin derivatives, rifapentine (RFP) and RLZ, have been tested for their abilities to shorten the duration of therapy or function as drugs which can be used in a once-weekly regimen. Both RFP and RLZ have been shown to be effective in treating tuberculosis in the murine model when given as intermittent therapy (once weekly) (2, 5). Studies done previously in our laboratory (8) and by Reddy et al. (10) have shown the potential of RLZ to shorten the duration of therapy. In our experiment, 6 weeks of RLZ treatment led to a nonculturable state. Reddy et al. (10) achieved a nonculturable state after 12 weeks of RLZ treatment. Regrowth was observed following the cessation of therapy in both studies.

We combined INH with RLZ and compared the results obtained with those drugs with the results obtained with RIF-INH. Treatment with RLZ-INH for 6 weeks led to a nonculturable state for both the spleens and lungs of mice, while 12 weeks of RIF-INH treatment was required to achieve the same result. Regrowth was observed 1 month following the cessation of 12 weeks of therapy in the RIF-INH group, whereas no regrowth was observed throughout a 6-month observation period in mice that received RLZ-INH (8).

The present study was performed to determine the minimum treatment period required to achieve and maintain a nonculturable state following the cessation of therapy. Although 6 and 8 weeks of RLZ-INH treatment led to a nonculturable state, regrowth occurred in a significant number of mice following the cessation of therapy. A minimum of 10 weeks of RLZ-INH treatment was required to achieve and maintain a nonculturable state.

The question of whether PZA could decrease the duration of treatment was then addressed. In humans, the addition of PZA to the standard RIF-INH regimen decreased the duration of treatment from 9 to 6 months. PZA is effective only during the first 2 months of therapy (11).

In this study, PZA was combined with RLZ-INH for both short-term (3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-week) and long-term (6-, 8-, and 10-week) treatments. The results indicated that the only significant contribution of PZA to RLZ-INH treatment was at the earliest time point studied, which was 3 weeks. PZA, in combination with RLZ-INH, did not reduce the treatment time required to reach a nonculturable state. PZA did, however, have an effect on the number of mice in which regrowth occurred (although it was not statistically significant). In future experiments it would be beneficial to have larger numbers of mice per group to increase the likelihood of measuring a statistically significant difference between treatment groups. It would also be of interest to compare RLZ-INH treatment with RLZ-INH-PZA treatment at time points earlier than 3 weeks to see if the difference in treatment regimens is present prior to 3 weeks.

It is unclear whether RLZ will be developed for human therapy. Due to its remarkable activity, it can (in combination with INH) significantly shorten the duration of therapy compared to that required for RIF-INH, as demonstrated in the murine model. This suggests that ultra-short-course therapy (3 months or less) is an attainable goal, which should be pursued through the development of improved antimycobacterial agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the NCDDG-OI program, cooperative agreement U19-AI40972 with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and a grant from Kaneka Corporation, Osaka, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.British Thoracic Society. A controlled trial of 6 months' chemotherapy in pulmonary tuberculosis. Final report: results during the 36 months after the end of chemotherapy and beyond. Br J Dis Chest. 1984;78:330–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks J V, Orme I M. Evaluation of once-weekly therapy for tuberculosis using isoniazid plus rifamycins in the mouse aerosol infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3047–3048. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniel W W. Applied nonparametric statistics. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin Co.; 1978. The Fisher exact test; pp. 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox W. The chemotherapy of pulmonary tuberculosis: a review. Chest. 1979;76S:785–796. doi: 10.1378/chest.76.6_supplement.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grosset J, Lounis N, Truffot-Pernot C, O'Brien R J, Raviglione M C, Ji B. Once-weekly rifapentine-containing regimens for treatment of tuberculosis in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1436–1440. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9709072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly B P, Furney S K, Jessen M T, Orme I M. Low-dose aerosol infection model for testing drugs for efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2809–2812. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klemens S P, Grossi M A, Cynamon M H. Activity of KRM-1648, a new benzoxazinorifamycin, against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a murine model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2245–2248. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klemens S P, Cynamon M H. Activity of KRM-1648 in combination with isoniazid against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a murine model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:298–301. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchison D A. How drug resistance emerges as a result of poor compliance during short course chemotherapy for tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy M V, Luna-Herrera J, Daneluzzi D, Gangadharam P R J. Chemotherapeutic activity of benzoxazinorifamycin, KRM-1648, against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in C57BL/6 mice. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1996;77:154–159. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singapore Tuberculosis Service/British Medical Research Council. Clinical trial of six-month and four-month regimens of chemotherapy in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;119:579–585. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.119.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snider D E, Rogowski J, Zierski M, Bek E, Long M W. Successful intermittent treatment of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis in six months: a cooperative study in Poland. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125:265–267. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snider D E, Graczyk J, Bek E, Rogowski J. Supervised six-months treatment of newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis using isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide with and without streptomycin. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130:1091–1094. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto T, Amitani R, Suzuki K, Tanaka E, Murayama T, Kuze F. In vitro bactericidal and in vivo therapeutic activities of a new rifamycin derivative, KRM-1648, against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:426–428. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]