Abstract

Objective:

To determine if any of maternal pre-delivery soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), placental growth factor (PIGF) or sFlt-1/PIGF ratio correlate with either perceived stress scale (PSS) or verbal numeric rating scale pain scores (VNRS).

Methods:

Among 50 severe pre-eclamptic and 90 normotensive pregnant women observed from ≤48 hours before delivery until day 3 postpartum, the correlation between the following were performed: (i) serum concentrations of each angiogenic factor (sFlt-1, PIGF and sFlt-1/PIGF ratio) sampled within 48 hours before childbirth and a 4-item PSS (pre-delivery and one-off 48 – 72 hours postpartum score); (ii) the same angiogenic factors above and VNRS ranging 0 – 10; and (iii) PSS and VNRS (both pre-delivery and postpartum).

Results:

In the normotensive group, there was a positive correlation between sFlt-1 and postpartum PSS (rho +0.214 and p = 0.043), and between sFlt-1/PIGF ratio and postpartum PSS (rho +0.213 and p = 0.044). In normotensive or sPE, there were non-significant: negative correlations between PIGF and postpartum PSS, p >0.096; and positive correlations between pre-delivery PSS and pre-delivery VNRS, p >0.053. Other correlations were uninformative.

Conclusion:

Maternal pre-delivery sFlt-1/PIGF ratio in normotensive pregnancy is a promising biomarker for identifying risk of increased postpartum PSS to enable early counselling.

Keywords: maternal mental health, pain score, perceived stress, placental growth factor, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1

Synopsis

Elevation in maternal pre-delivery concentration of sFlt-1/PIGF ratio in normotensive pregnancy is associated with an increase in postpartum perceived stress

1. Introduction

Postpartum stress increases the susceptibility to maternal illnesses, results in poor growth of the infant and may adversely disrupt social relationships [1-5]. Therefore, early (pre-delivery) detection of postpartum stress is important and may be of clinical use. Stress (which refers to a phenomenon where the adaptive capacity of an organism is exceeded due to environmental demands results in psychological and biological changes that increases the risk for a disease) [6] interferes with vascular health [7] and angiogenesis [8].

The maternal serum level of angiogenic factors such as placenta growth factor (PIGF), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and their ratio (sFlt-1/PGIF) have been used mainly in women with pre-eclampsia (PE) [9] and some data suggests that angiogenic factors may have association with stress-related conditions [10]. Notably, the effects of different types of stress [11] on angiogenesis is variable. For instance, pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) are elevated in women with an exhaustion disorder [10]. In another study, however, women with an exhaustion disorder in comparison with controls had decreased levels of VEGF, EGF and neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [12]. Of note, pain also has a psychological perspective and homeostasis of VEGF affects levels of pain with majority of studies supporting pro-nociceptive effects of VEGF-A although one VEGF-A splice form shows anti nociceptive effect [13].

Is there some association such as correlation between angiogenic factor-level and peripartum stress or pain? The authors attempted to determine this, of which clarification may be of some use in early detection and management of postpartum stress disorders. For instance, it may prompt early peripartum interventions such as intense counselling that may prevent future impaired mental health. Osman H, et al., (2014) showed that interventions such as a video on how to deal with common postpartum stressors and 24-hours telephonic support services provided to mothers early in the postpartum period reduces postpartum stress [14]. Additionally, possible therapeutic manipulation of the levels of angiogenic factors may assist in managing peripartum stress and pain [9]. The aim of this study, therefore was to determine the strength of association between maternal pre-delivery levels of angiogenic factors (sFlt-1, PIGF and sFlt-1/PIGF) and perceived stress as well as pain score before and after childbirth in pre-eclampsia with severe features (sPE) and normotensive pregnancies. The strength of association between the perceived stress and pain (both measured in the pre-delivery and postpartum periods) were also assessed.

2. Materials and methods

Regulatory Permissions

University of KwaZulu-Natal approved the research protocol (BE236/14). Participants consented before participation.

Study design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Study setting and duration

The study was conducted in a regional hospital in South Africa from August - December 2015.

Research Participants

Healthy normotensive women and those with sPE who had caesarean delivery at the study site were recruited as participants. This study is an arm of a base study that involved assessment of angiogenic imbalance (sFlt-1/PIGF ratio) among sPE and normotensive women to detect the ability of the biomarker to predict postpartum antihypertensive drug requirement [15]. Women with PE without severe features were excluded because angiogenic imbalance is usually not pronounced in them. Additionally, healthy women who had normal vaginal delivery are usually discharged from the hospital six hours postpartum. Due to hospital overcrowding at the study setting, healthy normotensive women who had vaginal delivery were excluded as data collection from them either as in- or out-patient was not feasible. Women with the following conditions were also excluded: multiple gestation, diabetes, connective tissue diseases and those booked for emergency caesarean delivery (CD) while in active phase of labour.

Pre-eclampsia was defined as development of new-onset hypertension (blood pressure 140/90 mmHg) at ≥20 gestational weeks with either significant proteinuria or target organ damage typical of PE. sPE was defined based on presence of any of the following features including systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥160 mmHg, diastolic BP ≥110 mmHg, pulmonary oedema, platelet count <100 X 109/L, elevated liver transaminases ≥70 IU/L, HELLP syndrome, serum creatinine ≥90 μmol/L, features of imminent eclampsia (such as headache, blurred vision and epigastric pain). Due to the high burden and severity of PE in the study setting, pre-eclamptic women who had fetal growth restriction and or proteinuria ≥3g/24 hours were included as sPE. The authors are not oblivious of the controversy on diagnostic criteria for sPE including the recent recommendations by the European guideline to consider proteinuria of ≥2g/24 hours as an indication for increased surveillance [16]. Notably, the decision for delivery in sPE were based on the indications approved by the International Society for Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy [17].

Spinal anaesthesia was the main method of anaesthesia for CD in the study setting. Hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine 1.8 ml mixed with 0.2 ml [10 μg] of fentanyl was the agent used for spinal anaesthesia. Where spinal anaesthesia was contraindicated, ineffective or impossible, general anaesthesia was used. Epidural analgesia was rarely used due to challenges with monitoring. In the immediate postpartum period, acetaminophen and opioid based analgesia mainly pethidine were prescribed.

Numeric rating scale of pain

An acceptable and widely used method of assessing pain in adults and children > 6 years of age is the numeric rating scale [18]. The most commonly used pain score is the version of numeric rating scale called verbal numeric rating scale-11 (VNRS) that has a score of 0 - 10 [19]. The VNRS has high correlation with other scales for measuring intensity of pain including verbal analogue scale (VAS).

4-item perceived stress scale

A popular method of assessing stress is the use of the 4-item perceived stress scale (PSS). The PSS has been evaluated in many countries and has shown satisfactory psychometric properties in an African population [20]. The 4-item PSS is acceptable to investigators because it has been validated in pregnancy and found to demonstrate acceptable psychometric properties in detecting stress, depression, quality of life and anxiety [21]. Moreover, its brevity makes it a quick and easy instrument to administer [21]. The 4-item PSS tool is freely available online and does not require permission to be used for educational purposes or academic research [22].

Each of the 4 questions/items in the 4-item PSS has 5 possible responses in a Likert scale and each respondent chooses one option/score: 0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, 4 = very often [22]. Questions 2 and 3 are positive affirmation of ability to cope with stress and the responses to them are reversed during computation thus 0 = 4, 1 = 3, 2 = 2, 3 = 1 and 4 = 0. The sum of the scores in the four questions constitute the 4-item PSS score. It assesses the feelings and thought in the last one month [22] and has been used to assess perceived stress in obstetric patients [21].

Data collection

Information about the study was provided to pregnant women attending antenatal care at the study setting. Subsequently, pregnant women booked for CD were offered the opportunity to participate in the study. Again, each patient gave informed consent before participation. Within 48 hours (preferably within 24 hours) before CD, 4-item PSS score and VNRS were obtained from each participant. Thereafter and within the same 48 hours (preferably within 24 hours) before delivery, peripheral venous blood was collected from each patient for measurement of serum concentration of sFlt-1 and PIGF.

Each blood sample was collected with an aid of a vacutainer in SST II advance yellow with gel tube. The samples were centrifuged in the laboratory at room temperature for 10 minutes at a speed of 3000 rpm using Rotina 380 R benchtop centrifuge (Andreas Hettich GmbH & Co. KG, Germany). The serum was collected in a cryotube, stored at −20 °C and measurement of the angiogenic factors were performed in batches at an independent laboratory (Ampath Laboratory, Durban, South Africa) within one month using Roche Elecsys Platform (Roche Diagnostics, Germany).

Within 48 - 72 hours postpartum, 4-item PSS score was recorded. On postpartum days 0, 1, 2 and 3, VNRS scores were obtained. A trained midwife collected the data. The principal investigator supervised and also assisted with data collection.

Statistical analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics and normality were assessed. Summary statistics are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for skewed data. Non-normally distributed dependent variables were transformed, where applicable, for instance to perform repeated measure two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on “longitudinal” data [23]. The Spearman’s correlation was used to determine the correlation between: (i) Pre-delivery angiogenic factors and stress; (ii) Pre-delivery angiogenic factor and pain; and (iii) Pain and stress. Both pain and stress were measured during the pre-delivery and postpartum periods (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram on data collection

Overall, significant level was set at p <0.05.

3. Results

Demography

All participants were of African ancestry. The median age including the interquartile range (IQR) of the normotensive and sPE groups were 28 (7) and 23 (11) years, P = 0.001 respectively. Primigravidae were 8.9% (8/90) in the normotensive and 46% (23/50) in the sPE groups, p <0.001. The body mass index (kg/m2) summarized as median and IQR were 29.5 (8.3) in the normotensive group and 26.8 (6) in the sPE group, p = 0.028.

Anaesthesia

The type of anaesthesia used for delivery was spinal in 45/50 (90%) and 86/90 (95.6%) of sPE and normotensive women respectively. General analgesia was used in 1/50 (2%) of the normotensive group. Conversion from spinal to general anaesthesia occurred in 1/50 (2%) of sPE and 2/90 (2.2%) of normotensive women. Epidural analgesia was used in 1/90 (1.1%) of normotensive women. Data on the method of anaesthesia was missing in 3 sPEs and one normotensive participants.

sFlt-1/ PIGF ratio

The blood samples were planned to be collected on the day of planned CD. In few participants, however, the CD was deferred particularly in normotensive women due to logistic challenges and prioritization of other patients that required treatment for more severe life-threatening emergency conditions. In some of these participants, CD was conducted before the research assistant could repeat the blood collection. Of the total 140 participants, 130 (92.9%) had their blood collected less than 24 hours before CD: 47/50 (94%) sPE and 83/90 (92.2%) normotensive women. In the remaining participants, blood was collected within 48 hours prior to the CD.

The median (and IQR) of sFlt-1 (pg/ml) was 3549.0 (2634.8) in normotensive and 11264.5 (7226.0) in sPE. PIGF (pg/ml) was 429.6 (671.9) in normotensive and 59.5 (79.6) in sPE. The median of sFlt-1/PIGF ratio were 7.25 (17.9) in the normotensive group and 179.1 (271.2) in sPE.

Pre- and post-delivery 4-item PSS

The median with IQR of 4-item PSS during pre- and post-delivery periods were 1.0 (4.0) and 2 (4.3) in the normotensive, and 3.0 (6.0) and 3.0 (5.3) in sPE respectively. There was no significant effect of time on PSS, p = 0.152. Participant’s group had no effect on PSS, p = 0.703.

Daily verbal numeric rating score of pain

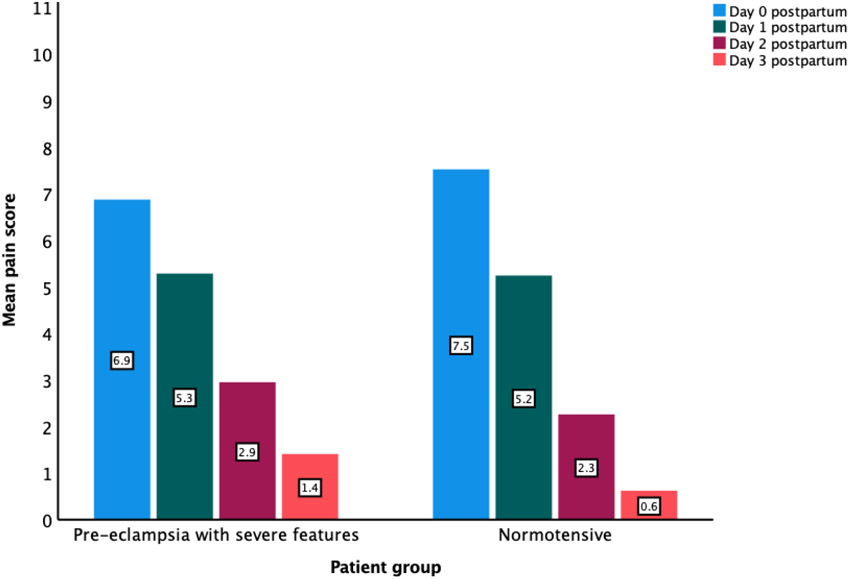

The mean ± SD of pre-delivery VNRS of pain were 0.3 ± 1.3 and 0.02 ± 0.1 in normotensive and sPE groups respectively. On postpartum days 0 – 3, the mean pain scores were 7.5 ± 2.5, 5.0 ± 2.1, 2.3 ± 1.9 and 0.6 ± 1.3 in normotensive group and 6.9 ± 2.8, 5.3 ± 2.1, 2.9 ± 2.2 and 1.4 ± 1.9 in sPE (Figure 2). Time had significant effect on VNRS of pain (F-ratio 130.9, p < .001, pη2 = 0.862). There was significant interaction between time and group (F-ratio 2.8, p= .033, pη2 = 0.116).

Figure 2.

Verbal Numerical Rating Scale (VNRS) of pain score (ranging 0 to 10) on postpartum days 0 to 3

Correlation between angiogenic factors and 4-item perceived stress score

A mixed pattern of both positive and negative correlation were observed (Table 1). There was a positive correlation between sFlt-1 and 48 – 72 hours postpartum PSS across the two groups (normotensive and sPE groups) with significant association existing in the normotensive group (rho +0.214 and p = 0.043). A positive correlation also existed across all the two groups between sFlt-1/PIGF ratio versus 48 - 72 hours postpartum PSS although a statistically significant association was only obtained in normotensive group (rho +0.213 and p = 0.044). Across the groups, non-significant negative correlations existed between PIGF and 48 – 72 hours postpartum PSS, p > 0.096.

TABLE 1.

Correlation between predelivery angiogenic factors and the total 4-item perceived stress score

| Pre- delivery angiogenic factor |

Total 4-item perceived stress scale (PSS) |

Spearman’s correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normotensive, n = 90 | sPE, n = 50 | ||||

| Correlation coefficient | P value | Correlation coefficient | P value | ||

| sFlt-1 | |||||

| Pre-delivery | +0.023 | 0.828 | −0.124 | 0.390 | |

| Within 48 −72 hours postpartum | +0.214 | 0.043a | +0.085 | 0.559 | |

| PIGF | |||||

| Pre-delivery | −0.181 | 0.088 | +0.134 | 0.355 | |

| Within 48 −72 hours postpartum | −0.177 | 0.096 | −0.141 | 0.330 | |

| sFlt-1/PIGF ratio | |||||

| Pre-delivery | +0.160 | 0.133 | −0.183 | 0.203 | |

| Within 48 −72 hours postpartum | +0.213 | 0.044a | +0.130 | 0.369 | |

Abbreviation: PIGF, placental growth factor (PIGF); PSS, 4-item perceived stress scale; sPE, Pre-eclampsia with severe features; sFlt-1, Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1.

Significant P value.

Correlation between angiogenic factors and verbal numeric rating score of pain

The correlation results are shown in Table 2. Amongst the sPE group on postpartum day 2, there was a statistically significant negative correlation between sFlt-1 and VNRS (rho −0.342 and p = 0.017) and between sFlt-1/PIGF ratio and VNRS (rho −0.303 and p = 0.037) . In sPE group on postpartum day 3, there was a statistically significant negative correlation between pre-delivery sFlt-1 and VNRS (rho −0.465 and p = 0.003).

TABLE 2.

Correlation between pre-delivery angiogenic factors and the daily verbal numeric rating score of pain

| Angiogenic factor |

Daily verbal numeric rating score (VNRS) of pain |

Spearman’s correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normotensive, n = 90 | sPE, n = 50 | ||||

| Correlation coefficient |

P value | Correlation coefficient | P value | ||

| sFlt-1 | |||||

| Pre-delivery | +0.188 | 0.076 | −0.035 | 0.811 | |

| Postpartum day 0 | −0.108 | 0.309 | −0.075 | 0.608 | |

| Postpartum day 1 | −0.056 | 0.606 | −0.231 | 0.110 | |

| Postpartum day 2 | +0.067 | 0.541 | −0.342 | 0.017a | |

| Postpartum day 3 | −0.173 | 0.230 | −0.465 | 0.003a | |

| PIGF | |||||

| Pre-delivery | −0.164 | 0.124 | +0.015 | 0.918 | |

| Postpartum day 0 | +0.053 | 0.618 | −0.027 | 0.854 | |

| Postpartum day 1 | −0.092 | 0.392 | +0.140 | 0.339 | |

| Postpartum day 2 | −0.025 | 0.816 | +0.169 | 0.251 | |

| Postpartum day 3 | +0.236 | 0.098 | +0.124 | 0.453 | |

| sFlt-1/PIGF ratio | |||||

| Pre-delivery | +0.173 | 0.104 | −0.054 | 0.707 | |

| Postpartum day 0 | −0.102 | 0.337 | −0.035 | 0.812 | |

| Postpartum day 1 | +0.043 | 0.693 | −0.231 | 0.110 | |

| Postpartum day 2 | +0.059 | 0.589 | −0.303 | 0.037a | |

| Postpartum day 3 | −0.248 | 0.082 | −0.293 | 0.070 | |

Abbreviation: PIGF, placental growth factor (PIGF); sPE, Pre-eclampsia with severe features; sFlt-1, Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1.

Significant p-value.

Correlation between perceived stress score and verbal numeric rating score of pain

The correlation between 4-item PSS and VNRS of pain showed a mixed pattern (Table 3). There was a non-significant positive correlation (across the two groups) between pre-delivery PSS and pre-delivery VNRS, p >0.53.

TABLE 3.

Correlation between 4-item perceived stress score and verbal numeric rating score of pain

| 4-item perceived stress score |

Daily verbal numeric rating score (VNRS) of pain |

Spearman’s correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normotensive, n = 90 | sPE, n = 50 | ||||

| Correlation coefficient |

P value | Correlation coefficient | P value | ||

| Pre-delivery | |||||

| Pre-delivery | +0.205 | 0.053 | +0.246 | 0.086 | |

| Postpartum day 0 | −0.102 | 0.336 | −0.122 | 0.404 | |

| Postpartum day 1 | +0.039 | 0.717 | +0.090 | 0.540 | |

| Postpartum day 2 | +0.71 | 0.515 | +0.275 | 0.058 | |

| Postpartum day 3 | +0.016 | 0.910 | +0.024 | 0.884 | |

| 48 – 72 hours Postpartum | |||||

| Pre-delivery | +0.180 | 0.089 | +0.245 | 0.087 | |

| Postpartum day 0 | −0.092 | 0.390 | −0.044 | 0.766 | |

| Postpartum day 1 | −0.094 | 0.385 | −0.020 | 0.893 | |

| Postpartum day 2 | +0.063 | 0.565 | −0.062 | 0.677 | |

| Postpartum day 3 | −0.051 | 0.726 | +0.039 | 0.812 | |

Abbreviation: sPE, Pre-eclampsia with severe features.

4. Discussion

Main findings

In the normotensive group, there was a positive correlation between the pre-delivery levels of sFlt-1 (or sFlt-1/PIGF ratio) and 48 – 72 hours postpartum PSS, p < 0.044. In both normotensive and sPE, there were non-significant negative correlations between PIGF and postpartum PSS, p > 0.096. In both groups, there were non-statistically significant positive correlations between pre-delivery VNRS and pre-delivery PSS, p > 0.053.

Strengths and Limitations

Many experts including 47 editors of 35 leading critical care, sleep and respiratory journals recommended that the identification of a confounder (to be controlled in a study) should be based on a prior knowledge and its plausible biological effects [24, 25]. Unfortunately, the variability in the relationship between pain and stress makes the a priori identification challenging in this study. This stems from the fact that stress is subjective and has wide physiological effects [26-30]. It is often linked with and may be expressed as pain although both have occasional paradoxical/controversial relationship; for instance, acute stress may induce analgesia and mask pain from an injury [28, 29]. Regardless, during the data analysis in the present study, we could not identify any confounding variable in the dataset. Understandably, an early work on the relationship among agniogenic factor, pain and stress in pregnant and postpartum women (sPE and healthy normotensive women) in a single health facility may not reveal all the existing relationship. Furthermore, we are aware that the administration of anaesthesia and analgesia reduces pain. Unfortunately, it will be inappropriate to withhold anaesthesia and analgesia because of the index study. However the effects of analgesia and anaesthesia on the study is expected to be minimal given that all the participants had CD and received anaesthesia and analgesia. Additionally, the side-effects of medications such as antihypertensives may contribute to the perceived feelings particularly among pre-eclamptic patients; however, the use of antihypertensive is acceptable. Of the 50 women with sPE, 49 (98%) received antihypertensive medication and their exclusion from the study or analysis will defeat the purpose of the study. Furthermore, maternal personality may confound perception [31] and influence the score of the PSS. Unfortunately, maternal personality just like genetic predisposition is an innate quality that may pre-dispose to stress. Future studies aimed at assessing the influence of maternal personality on peripartum perceived stress is proposed. Additionally, participants were not followed-up to detect development of mental health disorders but the duration of monitoring was informed by astute feasibility study. Another important consideration is that CD might have affected PSS. However, it is not every pregnant woman that prefers vaginal birth to CD. In the present study, all participants had CD that was performed on indication. To show the effect/influence of mode of delivery on peripartum PSS, future studies involving pregnant women that are planned for either vaginal birth or CD should be conducted and the participants followed up in the postpartum period.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to assess the correlation between pre-delivery levels of sFlt-1, PIGF or sFlt-1/PIGF versus peripartum (i) PSS and (ii) pain. The index study provides valuable insight into future studies. Understandably, PSS is a good instrument for assessing perceived stress in the peripartum period. Our study, however, leads the way for future studies that may show that another modality such as angiogenic factors can be useful for detecting, predicting, and treating perceived stress in the peripartum period.

Interpretation

In normotensive patients, the higher the concentration of pre-delivery sFlt-1 (or sFlt-1/PIGF ratio) the higher the PSS in the immediate postpartum period, p < 0.044. In the same normotensive group, the lower the concentration of pre-delivery PIGF the higher the postpartum PSS although not statistically significant, p = 0.096. We argue that the normotensive women did not develop PE due to lack of maternal susceptibility which is an essential “risk factor” for the disease [9]. It is possible that the angiogenic imbalance that exist in sPE and the slowness of sFlt-1 to return to normal in sPE (when compared to normotensive pregnancy) following childbirth [32], makes it difficult to detect informative correlation between angiogenic factors versus VNRS. Future studies (with large sample sizes) that evaluate the effects of various peripartum conditions such as breastfeeding and peripartum concentration of prolactin on levels of peripartum angiogenic factors are suggested.

In both the normotensive and sPE groups, there was a trend towards positive correlation between pre-delivery VNRS and pre-delivery PSS, p > 0.053. This means that, in the normotensive and sPE, the pre-delivery PSS tend to increase with increasing pre-delivery VNRS of pain. Pain is a stressful event that may increase PSS.

This index study shows that women with sPE have a trend towards having increased PSS. Of note, other studies show that mental health illness is a risk factor for pregnancy complications including PE [33]. For instance, elevated perceived prenatal stress is associated with development of future impaired mental health such as increased anxiety in children from the same pregnancy [34]. This may be due to the fact that chronic stress or repeated acute stress alters glucocorticoid genes by transcriptome and or epigenome. These result in impaired allostasis which propel weathering (premature aging) and development of diseases [35]. In the present study, there was an increase in PSS from the pre- to immediate post-partum period at least in the normotensive women. This resonates with other reports and gives credence to recommendation of implementing stress-reducing activities such as biofeedback during pregnancy [35]. These signify that activities in the peripartum period are stressful and women require optimal support during this period.

5. Conclusion

In normotensive pregnant women, increasing levels of pre-delivery sFlt-1/PIGF ratio are associated with worsening of the 48 – 72 hours postpartum PSS. Increasing pre-delivery VNRS of pain has a trend towards worsening pre-delivery PSS. These findings may guide profiling of patients for targeted intense counselling. To explain, a possible way to use the data from this study given the finding (of a significant positive correlation between pre-delivery sFlt-1/PIGF and postpartum stress in healthy normotensive pregnant women) is to regard normotensive women who have high levels of sFlt/PIGF ratio as being more likely to have increased levels of postpartum stress. Therefore, those with higher levels of sFlt-1/PIGF than others should be prioritized for close monitoring and early interventions that prevent stress disorders. Future studies are recommended to substantiate or refute our findings. Until then, measurement of angiogenic factors for the sole purpose of managing peripartum stress is not recommended.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to (i) Roche, South Africa for providing the reagents for measurements of serum levels of the angiogenic factors and (ii) Ampath Laboratories, Westridge, Durban, South Africa for performing the laboratory analysis of the angiogenic factors.

Funding

This research work was supported by grant (number: 5R24TW008863) from the Office of Global AIDS Coordinator and the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health (NIH OAR and NIH OWAR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the government.” The funders did not play any role in the study design, collection of data, statistical analysis, decision to publish the research findings and writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Oyetunji A, Chandra P. Postpartum stress and infant outcome: A review of current literature. Psychiatry Res 2020;248:112769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinsella MT, Monk C. Impact of maternal stress, depression and anxiety on fetal neurobehavioral development. Obstet Gynecol 2009;52(3):425–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung CH, Chung HH. The effects of postpartum stress and social support on postpartum women's health status. J Adv Nurs 2001;36(5):676–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maniam J, Antoniadis C, Morris MJ. Postpartum stress during the early postnatal period has long-lasting effects on metabolic profile in rat dams. Obes Res Clin Pract 2014;8(Suppl 1):70–1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alderdice F, Gargan P. Exploring subjective wellbeing after birth: A qualitative deductive descriptive study. Eur J Midwifery 2019;3(March):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU, eds. Measuring stress: a guide for health and social scientists. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piao L, Zhao G, Zhu E, Inoue A, Shibata R, Lei Y, et al. Chronic Psychological Stress Accelerates Vascular Senescence and Impairs Ischemia-Induced Neovascularization: The Role of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4/Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-Adiponectin Axis. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6(10):e006421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duman RS. Neurotropic mechanisms of depression: Animal and Human Studies. In: Charney DS, Nestler EJ, Sklar P, Buxbaum JD, editors. Charney and Nestler's Neurobiology of Mental Illneses. 5 ed. USA - OSO: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngene NC, Moodley J. Role of angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis and management of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;14(1):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallensten J, Åsberg M, Nygren Å, Szulkin R, Wallén H, Mobarrez F, et al. Possible Biomarkers of Chronic Stress Induced Exhaustion - A Longitudinal Study. PLoS One 2016;11(5):e0153924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:607–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlman AS, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Glise K, Jonsdottir IH. Growth factors and neurotrophins in patients with stress-related exhaustion disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;109:104415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llorián-Salvador M, González-Rodríguez S. Painful Understanding of VEGF. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osman H, Saliba M, Chaaya M, Naasan G. Interventions to reduce postpartum stress in first-time mothers: a randomized-controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngene NC, Moodley J, Naicker T. The performance of pre-delivery serum concentrations of angiogenic factors in predicting postpartum antihypertensive drug therapy following abdominal delivery in severe preeclampsia and normotensive pregnancy. PLoS One 2019;14(4):e0215807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Cífková R, De Bonis M, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J 2018;39(34):3165–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown M, Magee LA, Kenny LC, Karumanchi SA, McCarthy F, Saito S, et al. The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens 2018;13:291–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castarlenas E, Miró J, Sánchez-Rodríguez E. Is the Verbal Numerical Rating Scale a Valid Tool for Assessing Pain Intensity in Children Below 8 Years of Age? J Pain 2013;14(3):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PainScale. Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). Available from: https://www.painscale.com/article/numeric-rating-scale-nrs (accessed 19 December 2020).

- 20.Manzar MD, Salahuddin M, Peter S, Alghadir A, Anwer S, Bahammam AS, et al. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale in Ethiopian university students. BMC Public Health 2019;19(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karam F, Bérard A, Sheehy O, Huneau M, Briggs G, Chambers C, et al. Reliability and Validity of the 4-Item Perceived Stress Scale Among Pregnant Women: Results From the OTIS Antidepressants Study. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35(4):363–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacArthur Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Perceived Stress Scale- 4 Item. Available from: https://macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/pss4.php (accessed 20 December 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall E Two-way ANOVAin SPSS. Available from: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.531212!/file/MASH_Twoway_ANOVA_SPSS.pdf (accessed 27 December 2020).

- 24.Hancox RJ. When is a confounder not a confounder? Respirology 2019;24:105–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lederer DJ, Bell SC, Branson RD, Chalmers JD, Marshall R, Maslove DM, et al. Control of Confounding and Reporting of Results in Causal Inference Studies: Guidance for Authors from Editors of Respiratory, Sleep, and Critical Care Journals. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019;16(1):22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association. Stress effects on the body 2021. Available from: https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body (accessed 14 August 2021).

- 27.American Psychological Association. How stress affects your health 2021. Available from: https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/health.

- 28.Flood P, Clark JD. Molecular Interaction between Stress and Pain. Anesthesiology 2016;124(5):994–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geva N, Pruessner J, Defrin R. Acute psychosocial stress reduces pain modulation capabilities in healthy men Pain 2014;155(11):2418–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard KS, Evans MB, Kjerulff KH, Downs DS. Postpartum Perceived Stress Explains the Association between Perceived Social Support and Depressive Symptoms. Womens Health Issues 2020;30(4):231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiPietro JA. Maternal Stress in Pregnancy: Considerations for Fetal Development. J Adolesc Health 2012;51(2):S3–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powers RW, Roberts JM, Cooper KM, Gallaher MJ, Frank MP, Harger GF, et al. Maternal serum soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 concentrations are not increased in early pregnancy and decrease more slowly postpartum in women who develop preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193(1):185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 2020;9(3):313–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis EP, Sandman CA. Prenatal Psychobiological Predictors of Anxiety Risk in Preadolescent Children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012;37(8):1224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Traylor CS, Johnson JD, Kimmel MC, Manuck TA. Effects of psychological stress on adverse pregnancy outcomes and nonpharmacologic approaches for reduction: an expert review. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020;2(4):100229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]