Abstract

Background:

Sensory over-responsivity has been linked to oral care challenges in children with special healthcare needs. Parents of children with Down syndrome (cDS) have reported sensory over-responsivity in their children, but the link between this and oral care difficulties has not been explored.

Aim:

Investigate relationship between sensory over-responsivity and oral care challenges in cDS.

Design:

Online survey examined parent-report responses describing their cDS’s oral care (5–14yrs; n=367); children were categorized as sensory over-responders (SORs) or sensory not over-responders (SNORs). Chi-square analyses tested associations between groups (SORs vs. SNORs) and dichotomous oral care variables.

Results:

More parents of SOR children, compared to SNOR, reported that: child behavior (SOR:86%, SNOR:77%; p<.05) and sensory sensitivities (SOR:34%, SNOR:18%; p<.001) make dental care challenging, their child complains about ≥3 types of sensory stimuli encountered during care (SOR:39%, SNOR:28%; p=.04), their dentist is specialized in treating children with special needs (SOR:45%, SNOR:33%; p=.03), and their child requires full assistance to brush teeth (SOR:41%, SNOR:28%; p=.008). No group differences were found in items examining parent-reported oral health or care access.

Conclusions:

Parents of SOR children report greater challenges than parents of SNOR children at the dentist and in the home, including challenging behaviors and sensory sensitivities.

Keywords: Down syndrome, oral health, sensory processing, dental care, access to care, barriers to care

Sensory processing challenges occur as a result of atypical detection, modulation, interpretation, and response to sensory information.1 These difficulties can present in a variety of forms, including over-responsiveness or under-responsiveness to sensory stimuli, and can negatively impact an individual’s participation in daily routines.1–4 Atypical responses to sensory stimuli have commonly been documented in various clinical populations, including those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD),5–8 Fragile X Syndrome,8–10 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,6,11–12 fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (Fjeldsted & Xue, 2019; Hen-Herbst et al., 2020; Jirikowic et al., 2020),13–15 and developmental coordination disorder.12,15–16

Although sensory processing challenges have been reported in mixed samples of children with developmental disabilities,5 only a small amount of literature exists examining the sensory processing of children with Down syndrome (DS), all of which report significant difficulties.17–20 Using parental questionnaire data (e.g., Sensory Profile, Short Sensory Profile), parents of children with Down syndrome most frequently report that their child exhibits challenges that fall within the probable-to-definite difference ranges compared to population normative values in two categories: low energy/weak and under-responsive/seeks sensation.17–19 Parents also have reported the presence of sensory sensitivities in the probable-to-definite difference ranges, specifically in the categories of tactile sensitivity (49–51%), visual/auditory sensitivity (38–52%), taste/smell sensitivity (30–35%), and movement sensitivity (32–34%).17–18 Challenges with sensory processing were overwhelmingly reported to have a significant impact on children’s daily life and were linked with maladaptive behavior and decreased activity participation and performance.17–19

One of many daily life areas affected by sensory challenges is oral care. Literature suggests that sensory processing difficulties, specifically over-responsivity to sensory stimuli, is linked to challenges with oral care in the home and dental office in children with disabilities.21–28 Parents of children with Down syndrome have reported similar sensory over-responsivities in their children,17–18,29 as well as uncooperative behaviors during oral care,29–30 but the link between these two factors has yet to be explored in this population. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between sensory over-responsivity and oral care challenges in children with Down syndrome.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey study was approved for human subjects by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Southern California (HS-15–00218) and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA-15–00047).

Participants & Recruitment.

Participants were parents who self-reported having a child with Down syndrome between 5 and 14 years of age. A convenience sample was recruited via email dissemination throughout the United States to Down syndrome-specific organizations, private disability-specific schools, occupational therapy clinics, and regional centers. The email invitation briefly introduced the research team and explained that we were recruiting families to participate in an online survey about sensory issues and oral care in their children with Down syndrome; responses were downloaded from REDCap without any identifying information, and families were sent a $15 Amazon giftcard for their participation by a team member not involved in analysis. As this was a pilot study to gather evidence in order to better design a clinical trial, there was no formal a priori sample size estimate.

Instruments.

Parents completed the Dental Care in Children Survey23,29,31 online to provide information regarding their child’s oral care at home and at the dentist in March 2019. The survey was crafted by the authors, reviewed and edited by an expert pediatric dentist, and then pilot tested with parents of children with special healthcare needs and parents of typically developing children (not included in this study sample). Although not a standardized tool, the Dental Care in Children survey has face validity and has been previously used in other research examining the oral care experiences of children with special healthcare needs and typically developing children.23,25,29,31,50

The survey, presented in English, was 48 items with dichotomous yes/no questions, Likert-scale questions, and open-ended questions including queries about toothbrushing (e.g., frequency, degree of assistance required, sensory-related responses), barriers and facilitators to care (e.g., fear, anxiety, sensory-related discomfort during care, behavioral difficulties, expertise of current dentist), and previous professional dental care experiences (e.g., difficulty with cleaning, use of restraint or pharmacological methods for routine prophylaxis, challenges locating or receiving care); participant demographics also were collected. A copy may be requested from the first author; see Stein Duker et al.23 for more details.

Parents were also asked to rate their child’s sensory sensitivity from 1 (not oversensitive) to 3 (moderately oversensitive) to 5 (very oversensitive) on each of eight modalities of sensory stimuli (e.g., touch, oral, taste, smell, sound, vibration, movement, light). Based on previous analysis of typically developing children,23 approximately 15% were reported to experience oversensitivity to three or more of these eight sensory modalities. Using these data, we created a cut score to categorize participants into two groups – Sensory Over-Responders and Sensory Not Over-Responders as 15% typically represents one standard deviation from the mean. Therefore, children whose parents reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity (i.e., scores of 3–5) on three or more of the eight sensory modalities were characterized as Sensory Over-Responders (SORs). The Sensory Not Over-Responders group (SNORs) included children whose parents reported moderate to extreme oversensitivity on two or fewer of the eight modalities.

Data Analysis.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). For descriptive purposes, frequencies and percentages were calculated for each of the demographic and oral care variables. Fisher’s Exact Probability tests and Chi-square tests were performed to test for associations between groups (Sensory Over-Responders vs. Sensory Not Over-Responders) and the dichotomous oral care variables. All tests were conducted at the .05 significance level.

Results

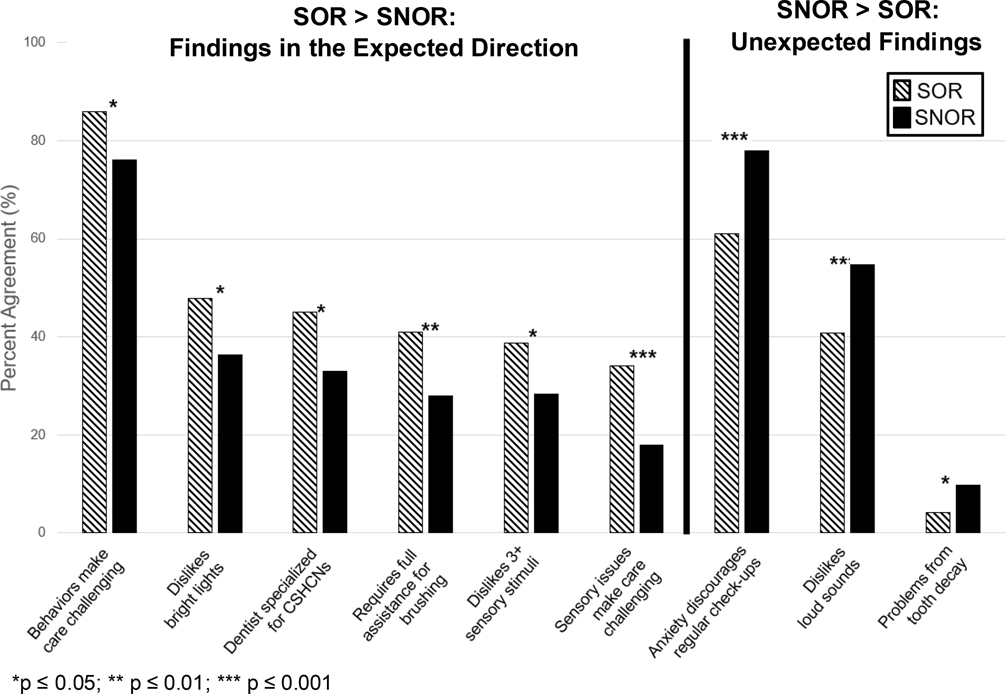

Of the 391 surveys completed, 19 were excluded because respondents did not confirm their child had a diagnosis of Down syndrome; an additional 5 were excluded because the sensory-related questions used to determine group were not completed. Therefore, a total of 367 surveys were included in these analyses. Significant results are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage of significantly different responses to oral care challenge questions by parents of SOR and SNOR children with Down syndrome.

Note. Sensory over-responders (SORs) were children whose parents reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on three or more (of eight total) sensory modalities; sensory not over-responders (SNORs) were parents who reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on two or fewer sensory modalities. Sample sizes for each question are as follows: Behaviors make care challenging: SOR n=137, SNOR n=220; dislikes bright lights: SOR n=142, SNOR n=225; Dentist specialized for CSHCNs: SOR n=134, SNOR n=215; Requires full assistance for brushing: SOR n=139, SNOR n=222; Dislikes 3+ sensory stimuli: SOR n=142; SNOR n=225; Anxiety discourages regular check-ups: SOR n=138, SNOR n=222; Dislikes loud sounds: SOR n=142, SNOR n=225; Problems from tooth decay: SOR n=136, SNOR n=215.

Participants

Participants were 367 caregivers of 5–14 year old children with Down syndrome (45% mothers, 55% fathers). Almost 40% of children (n=142) were categorized into the SOR group based on parent response to sensory questions; the remaining children were assigned to the SNOR group (61%, n=225). Children in both groups were predominantly male, white/Caucasian, and communicated using single words or phrases. Approximately half of each group was Hispanic or Latino. Maternal education was significantly different between groups, with the SNOR group more educated. Child age, sex, race, ethnicity, communication abilities, insurance status, and paternal education were comparable between the SOR and SNOR groups. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Children with Down Syndrome by Sensory Group.

| Demographic Characteristics | Sensory Not Over-Responders (SNORs) (n=225) M (SD) | Sensory Over-Responders (SORs) (n=142) M (SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (yrs) | 8.45 (1.9) | 8.49 (2.4) | 0.86 |

|

| |||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

|

| |||

| Sex | .06 | ||

| Male | 156 (69.3) | 85 (59.9) | |

| Female | 69 (30.7) | 57 (40.1) | |

| Race* | .52 | ||

| White, Caucasian | 182 (80.1) | 108 (76.1) | |

| Black or African American | 28 (12.4) | 22 (15.5) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 14 (6.22) | 4 (2.8) | |

| Native American or other Pacific Islander | 8 (3.6) | 4 (2.8) | |

| Asian | 7 (3.1) | 6 (4.2) | |

| Hispanic Status | .90 | ||

| Not Hispanic, not Latino | 113 (50.2) | 71 (50.0) | |

| Hispanic, Latino | 110 (48.9) | 71 (50.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Communication (My child is able to indicate his/her needs or wants using:_________) | .11 | ||

| Single words or phrases | 82 (36.4) | 56 (39.4) | |

| Sentences | 77 (34.2) | 44 (31.0) | |

| Pointing at pictures | 40 (17.8) | 14 (9.9) | |

| Gestures | 15 (6.2) | 13 (9.2) | |

| Screaming and/or yelling | 8 (4.0) | 12 (8.5) | |

| My child is unable to communicate | 2 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Child’s dental insurance status | .37 | ||

| State insurance | 95 (42.2) | 69 (48.6) | |

| Private insurance | 58 (25.8) | 37 (26.1) | |

| Parent pays out-of-pocket | 45 (20.0) | 19 (13.4) | |

| No insurance | 16 (7.1) | 12 (8.5) | |

| Missing | 11 (4.9) | 5 (3.5) | |

| Survey Respondent’s Relationship to Child | .89 | ||

| Mother | 101 (44.9) | 63 (44.4) | |

| Father | 123 (54.7) | 79 (55.6) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Maternal Education Level | .007 | ||

| Less than High School | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| High School or GED | 24 (10.7) | 30 (21.1) | |

| College | 166 (73.8) | 99 (69.7) | |

| Graduate Degree or above | 34 (15.1) | 11 (7.7) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Paternal Education Level | .14 | ||

| High School or GED | 15 (6.7) | 16 (11.3) | |

| College | 147 (65.3) | 97 (68.3) | |

| Graduate Degree or above | 61 (27.1) | 29 (20.4) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

Percentages do not equal 100% as participants could choose more than one answer.

Note. Sensory over-responders (SORs) were children whose parents reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on three or more (of eight total) sensory modalities; sensory not over-responders (SNORs) were parents who reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on two or fewer sensory modalities.

Oral Health

Overall, oral health as reported by the parent was comparable between the two sensory-based groups of children with Down syndrome. Slightly more parents reported poor oral health for their child with DS in the SOR group (SOR 42%, SNOR 38%), although the majority of parents in both groups reported good oral health (SOR 56%, SNOR 59%). SOR parents also reported a marginally, but not significant, higher frequency of habits which have the potential to negatively impact oral health in their children, including pica (SOR 55%, SNOR 48%) and pocketing food while eating (SOR 53%, SNOR 43%). Approximately 50% or more of parents in both groups reported that their child had experienced three or more cavities in both primary and permanent dentition, and that three or more primary and permanent teeth had been pulled due to tooth decay. Despite the high prevalence of pulled teeth due to decay in both groups, significantly more SNOR parents (10%) reported that tooth decay had led to problems with their child’s eating/nutrition or speaking (SOR: 4%; p<.05). See Table 2.

Table 2.

Parents of Children with Down syndrome Responses to Oral Health and Access to Care Questions by Sensory Group.

| Sensory Not Over- Responders (SNORs) M (SD) | Sensory Over-Responders (SORs) M (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| ORAL HEALTH | |||

|

| |||

| Parent perception of child’s oral health | (n=224) | (n=142) | .54 |

| Poor | 86 (38.4) | 60 (42.3) | |

| Good | 133 (59.4) | 79 (55.6) | |

| Excellent | 5 (2.2) | 3 (2.1) | |

| Child’s oral habits | (n=225) | (n=142) | |

| Pica (yes) | 108 (48.0) | 78 (54.9) | .20 |

| Bruxism (yes) | 132 (58.7) | 83 (58.5) | .97 |

| Pocketing food (yes) | 96 (42.7) | 75 (52.8) | .06 |

| Parent report of child’s primary dentition cavities history | (n=221) | (n=137) | <.05 |

| 2 or fewer | 72 (32.6) | 59 (43.1) | |

| 3 or more | 149 (67.4) | 78 (56.9) | |

| Parent report of child’s permanent dentition cavities history | (n=219) | (n=133) | .99 |

| 2 or fewer | 94 (42.9) | 57 (42.9) | |

| 3 or more | 125 (57.1) | 76 (57.1) | |

| Parent report of child’s primary teeth pulled due to decay | (n=220) | (n=137) | .08 |

| 2 or less | 93 (42.3) | 71 (51.8) | |

| 3 or more | 127 (57.7) | 66 (48.2) | |

| Parent report of child’s permanent teeth pulled due to decay | (n=215) | (n=135) | .10 |

| 2 or less | 89 (41.4) | 68 (50.4) | |

| 3 or more | 126 (58.6) | 67 (49.6) | |

| Child’s tooth decay has led to problems with eating (nutrition) or speaking | (n=215) | (n=136) | <.05 |

| No | 193 (89.8) | 130 (95.6) | |

| Yes | 22 (10.2) | 6 (4.4) | |

|

| |||

| ACCESS TO CARE | |||

|

| |||

| Ever experienced difficulty locating a dentist willing to provide child with care | (n=220) | (n=137) | .39 |

| No | 45 (20.5) | 23 (16.8) | |

| Yes | 175 (79.5) | 114 (83.2) | |

| Child ever refused treatment by a dental provider | (n=219) | (n=137) | .72 |

| No | 79 (36.1) | 52 (38.0) | |

| Yes | 140 (63.9) | 85 (62.0) | |

| Number of dental cleanings child received in last 12 months | (n=222) | (n=138) | .94 |

| 0–1 | 102 (45.9) | 64 (46.4) | |

| 2+ | 120 (54.1) | 74 (53.6) | |

| Child has regular dental clinic he/she goes to | (n=218) | (n=138) | .60 |

| No | 84 (38.5) | 57 (41.3) | |

| Yes | 134 (61.5) | 81 (58.7) | |

| Child’s dental practitioner is specialized in working with children with Down syndrome or other special health care needs | (n=215) | (n=134) | .03 |

| No | 144 (67.0) | 74 (55.2) | |

| Yes | 71 (33.0) | 60 (44.8) | |

Note. Sample sizes vary due to missing data. Sensory over-responders (SORs) were children whose parents reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on three or more (of eight total) sensory modalities; sensory not over-responders (SNORs) were parents who reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on two or fewer sensory modalities.

Access to Dental Services

Similar rates of parents in both groups reported challenges with accessing dental services for their child with Down syndrome. Approximately 80% of parents in both groups reported difficulty locating a dentist willing to treat their child and over 60% stated that their child had been refused treatment by a dental provider. Although not significantly different, parents of children in the SOR group endorsed at a slightly higher rate that dentists stated that these refusals were due to the child’s behavior problems (SOR 34%, SNOR 27%) and/or inadequate dentist/staff training to work with children with special health care needs (SOR 48%, SNOR 45%). Approximately 60% of parents in both groups reported that refusals were blamed on inadequate financial compensation; parents likewise reported that their finances limited the number of times they take their child with Down syndrome to the dentist each year. However, of those who had experienced refusals, dentists were rarely reported to refuse treatment due to not taking the child’s insurance (SOR 12%, SNOR 6%).

Despite reporting challenges locating and accessing care, approximately 95% of parents in both groups reported that their child had received at least one dental cleaning in the previous year, with approximately 50% of each group reporting two or more cleanings. Approximately 60% of parents in both groups reported that their child went to a specific dental clinic for care; of those, over 90% of both groups reported seeing a specific dentist in that clinic. However, significantly more parents of children in the SOR group reported that their child’s dentist was specialized in working with children with Down syndrome or other special health care needs, compared to the providers treating children in the SNOR group (45% vs. 33%, p=.03). See Table 2.

Dental Care in the Home

Significantly more parents of SOR children reported that their child required full assistance when brushing their teeth in the home (41%), compared to parents of SNOR children (28%; p=.008). Non-significant trends in the expected direction were reported by parents in regard to experiencing difficulty with oral care in the home (SOR 66%, SNOR 60%). Of those who reported difficulty in the home, disliking the taste and texture of the toothpaste was slightly higher in the SOR group (SOR 57%, SNOR 46%), while both groups similarly endorsed that their child disliked the feeling of the toothbrush in his/her mouth (SOR 63%, SNOR 65%) and that their child gagged during toothbrushing (SOR 30%, SNOR 32%). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Parents of Children with Down syndrome Responses to Oral Care Questions about the Home and Dental Office by Sensory Group.

| Sensory Not Over- Responders (SNORs) M (SD) | Sensory Over-Responders (SORs) M (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| DENTAL CARE IN THE HOME | |||

|

| |||

| Assistance required to complete toothbrushing in the home | (n=222) | (n=139) | <.0001 |

| Full assistance | 61 (27.5) | 57 (41.0) | |

| Some physical assistance | 118 (53.2) | 64 (46.0) | |

| Verbal reminders | 41 (18.5) | 9 (6.5) | |

| Child is independent in brushing | 2 (0.90) | 9 (6.5) | |

| Difficulty with child’s toothbrushing on a daily basis | (n=222) | (n=140) | .31 |

| No | 88 (39.6) | 48 (34.3) | |

| Yes | 134 (60.4) | 92 (65.7) | |

|

| |||

| DENTAL CARE IN THE DENTAL OFFICE | |||

|

| |||

| Child’s experience at last dental cleaning | (n=222) | (n=138) | .10 |

| Negative experience | 20 (9.0) | 12 (8.7) | |

| Neutral experience | 111 (50.0) | 54 (39.1) | |

| Positive experience | 91 (41.0) | 72 (52.2) | |

| Child receives high quality of care from the dentist | (n=221) | (n=139) | .25 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 19 (8.6) | 11 (7.9) | |

| Neutral | 73 (33.0) | 35 (25.2) | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 129 (58.4) | 93 (66.9) | |

| Based on child’s reactions/behaviors at the dentist, difficulty level for dentist or hygienist to clean child’s teeth | (n=221) | (n=139) | .37 |

| Not at all difficult* | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mildly difficult | 34 (15.4) | 20 (14.4) | |

| Moderately difficult | 132 (59.7) | 75 (54.0) | |

| Extremely difficult | 55 (24.9) | 44 (31.7) | |

| If child had to go to the dentist tomorrow to have his/her teeth cleaned, how would he/she feel about it | (n=222) | (n=138) | .03 |

| Look forward to it as a reasonably enjoyable experience | 15 (6.8) | 22 (15.9) | |

| Wouldn’t care | 56 (25.2) | 28 (20.3) | |

| Would be a little uneasy | 113 (50.9) | 61 (44.2) | |

| Would be afraid* | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Would be extremely afraid | 38 (17.1) | 27 (19.6) | |

| My child’s uncooperative behaviors make dental appointments challenging | (n=220) | (n=137) | .04 |

| Strongly disagree* | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Somewhat agree | 50 (22.7) | 19 (13.9) | |

| Moderately-strongly agree | 170 (77.3) | 118 (86.1) | |

| My child’s sensory sensitivities make dental appointments challenging | (n=220) | (n=137) | <.001 |

| Strongly disagree* | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Somewhat-moderately agree | 181 (82.3) | 91 (66.4) | |

| Strongly agree | 39 (17.7) | 46 (33.6) | |

| At the dentist’s office, is your child afraid of, dislikes, or complains about: | (n=225) | (n=142) | |

| Loud sounds (yes) | 123 (54.7) | 58 (40.8) | .01 |

| Bright lights (yes) | 82 (36.4) | 68 (47.9) | .03 |

| Smells (yes) | 41 (18.2) | 36 (25.4) | .10 |

| Taste of toothpaste (yes) | 23 (10.2) | 20 (14.1) | .26 |

| Reclining in dental chair (yes) | 67 (29.8) | 49 (34.5) | .34 |

| Instruments placed in mouth (yes) | 125 (55.6) | 79 (55.6) | .99 |

| Child’s anxiety or response to dental treatment discourages you from regular check-ups | (n=222) | (n=138) | <.001 |

| No | 50 (22.5) | 54 (39.1) | |

| Yes | 172 (77.5) | 84 (60.9) | |

Note. Sample sizes vary due to missing data. Sensory over-responders (SORs) were children whose parents reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on three or more (of eight total) sensory modalities; sensory not over-responders (SNORs) were parents who reported moderate to extreme over-responsivity on two or fewer sensory modalities.

Not included in Chi-square analyses since both sensory groups reported zero values.

Dental Care in the Dental Office

Only 9% of parents in both groups reported that their child’s experience at his/her last cleaning was negative, and over 50% of parents agreed or believed that their child receives high quality care from the dentist (SOR 66%, SNOR 57%). Despite these overall positive perceptions, parents in both groups also reported challenges during professional oral care. Most challenges were endorsed slightly higher in the SOR group, including: dental cleanings being extremely difficult for the dentist to perform based on the child’s behaviors (SOR 32%, SNOR 25%), that their child would be extremely afraid to go to the dentist for a cleaning (SOR 20%, SNOR 17%), and that dental visits were more stressful for their child with DS compared to his/her typically developing sibling (SOR 15%, SNOR 11%). Although only slightly more SOR parents reported that uncooperative behaviors (SOR 52%, SNOR 49%) and sensory sensitivities (SOR 59%, SNOR 56%) increased at the dentist, significantly more SOR parents moderately-to-strongly agreed that those behavioral difficulties make dental appointments challenging (SOR 86% vs. SNOR 77%, p=.04) and strongly agreed that sensory sensitivities make dental appointments challenging (SOR 34% vs. SNOR 18%, p<.001).

Slightly more parents of SOR children reported that their child was afraid of, disliked, or complained about sensory stimuli encountered during dental care. For example, more parents of SOR children reported challenges with leaning back in the dental chair (SOR 35%, SNOR 30%), smells (SOR 25%, SNOR 18%), and taste of toothpaste or fluoride (SOR 14%, SNOR 10%); significantly more parents reported problems with bright lights (SOR 48% vs. SNOR 36%, p=.03) and reported difficulties with three or more types stimuli (of six choices) during care (SOR 39% vs. SNOR 28%, p=.04).

Other challenges were relatively equally endorsed. For example, similar frequencies of parents in both groups reported that their child experienced difficulty with the dentist placing instruments in their child’s mouth (56%), that their child’s dental provider used restraint sometimes/often (86–88%) or required pharmacological methods (53%) to complete a routine dental cleaning. However, although parents in both groups similarly endorsed that extreme anxiety was the reason pharmacological methods for routine care was needed (70–71%), more SOR parents attributed the need for pharmacological intervention to their child’s behavioral difficulties (SOR 56% vs. SNOR 48%, n.s.).

Lastly, some challenges were unexpectedly endorsed more frequently by parents of SNOR children. For example, significantly more SNOR parents reported challenges with loud sounds during dental care (SOR 41% vs. SNOR 55%, p=.01) and that their child’s anxiety or response to dental treatment discouraged them from bringing their child to the dentist for regular checkups (SOR 61% vs. SNOR 78%, p<.001). See Table 3.

Discussion

Although parents frequently note the presence of sensory sensitivities in their children with Down syndrome,17–20 the presence of sensory over-responsivity and the strong link between sensory sensitivities and difficulties with oral care previously reported in children with other special health care needs21–28 was not as clearly evident in our study results. For example, approximately 39% of our DS sample was categorized as sensory over-responsive, as compared to 79% of our previous ASD sample.23 Although most findings in our study were not significantly different between the two DS sensory groups, results were primarily in the expected direction, suggesting that children with DS and SOR experience slightly more challenges with oral care as compared to their SNOR counterparts.

In the home, our study found that children with DS and SOR experienced only slightly more challenges with toothbrushing and the taste/texture of toothpaste, compared to SNOR children, contrasting the significant differences reported by parents of children with ASD and SOR.23 However, our results do align with Bruni et al.’s17 report that over half of children with Down syndrome exhibit tactile sensitivities during grooming routines. Our results also suggest that SOR children with DS require greater assistance to complete toothbrushing than SNOR children; previous research has linked atypical sensory processing to challenges with the motor skills required to complete activities of daily living, such as toothbrushing.32 Parents’ similar reports of gagging in both DS sensory groups in our study may be linked, in part, to anatomical differences and medical conditions seen in people with DS,33 and not sensory sensitivities as found in children with ASD.23

During professional oral care, more parents of children with SOR, compared to SNOR, reported increases in uncooperative behaviors and sensory sensitivities at the dental office, which were reported significantly more often by SOR parents to make dental care more challenging for their children. These could, arguably, be one of the most important variables to consider when examining the impact sensory sensitivities may have on oral care, as uncooperative behaviors exhibited during care are reported to be one of the leading barriers to dentists’ treatment of children with special health care needs.34–38 Likewise, slightly more parents of children with SOR endorsed that their child had been refused care by a dentist due to their child’s behavior problems, as compared to parents of SNOR children with DS.

Dentists employ a variety of techniques to improve cooperation and experience for children with special health care needs.39 However, some of these behavior guidance techniques, such as those relying on communication (e.g., tell-show-do, ask-tell-ask), may be less suitable for children with DS due to auditory processing difficulties18 and/or the severity of intellectual disability.40 Due to the link between SOR and challenging dental visits, sensory adapted dental environments (SADE) may be an appropriate alternative approach to consider for this population. These environments do not rely on communication nor cognitive level, but rather focus on modifying the sensory features of the dental environment.21,26–28,39 Three pilot studies have reported preliminary efficacy of the SADE in decreasing behavioral and/or physiological distress in children with developmental disabilities26–28 and autism spectrum disorder.21

Similar to other children with special health care needs,31,41–43 parents of children with DS – in both sensory groups – overwhelmingly reported having experienced difficulty locating a dentist willing to treat their child. However, these difficulties were not significantly associated with sensory over-responsivity, suggesting that for children with Down syndrome, factors other than sensory over-responsivity influence access and utilization of preventive dental visits. Supported by our findings, dental provider education has been commonly reported as a barrier to dental care by both parents and providers of children with special health care needs.29,31,37–38,44–48

Despite reporting challenges accessing care at some time, over 95% of parents reported that their child had received a dental cleaning at least one time in the last year, with almost 50% of each group receiving two preventive visits and over 50% reporting that their child had a dental home. Interestingly, other research suggests that once families of children with Down syndrome locate a dentist, they are more likely to attend consistently compared to their non-Down syndrome peer or sibling,30 which may explain the high frequency of annual visits in our study sample.

Surprisingly, significantly more parents of children with DS who were not over-responsive to sensory stimuli reported that their child was afraid of, disliked, or complained about loud noises in the dental office when compared to children with DS and SOR. As hearing loss is common in children with DS,49 future research should include hearing loss as a potential variable of interest when examining over-responsivity to auditory stimuli. Although over 50% of parents of both sensory groups reported that their child’s anxiety or response to dental treatment discourages them from bringing their child for regular dental checkups – indicating that this is problematic regardless of sensory status – significantly more SNOR DS parents endorsed this item compared to SOR DS parents. The decreased endorsement of this survey item by SOR parents may be, in part, explained by their SOR children being treated significantly more often by dentists with extra training and specialization treating children with special healthcare needs. Therefore, it will be important to examine the role dentist expertise plays in parental perception of oral care challenges.

This study adds to our understanding of the relationship between sensory responsivity and oral care for children with DS. However, several limitations should be noted. Respondents came from a convenience sample of parents who completed an online survey and self-reported having a child with a DS diagnosis; therefore, no information regarding participant location, referral source, or response rate is available nor diagnostic confirmation of child’s diagnosis. Parents were not specifically asked to report sensory-related impairments in their children (e.g., visual, auditory); therefore, children with these types of impairments were not excluded from the current analyses. In addition, no formal dental examination or records review were conducted to confirm parent-reported oral health status and/or caries history. Lastly, respondents were only excluded if they did not confirm a DS diagnosis or did not answer the sensory-related questions used to determine placement into sensory group; therefore, incomplete surveys were included in analyses. Although there was minimal missing data (lowest response rate for any question was n=215 SNOR, n=134 SOR), the inclusion of incomplete surveys does have the potential to reduce the representativeness of the sample and decrease power.

Conclusions

Superiority analyses did not demonstrate a difference in oral care in the home and dental office between SOR children with DS and SNOR children with DS. However, multiple non-significant trends toward greater challenges with oral care in the home and dental office were reported by parents of SOR children with DS compared to parents of SNOR children with DS.

Significantly more parents of children with DS and SOR, compared to SNOR children with DS, reported that: child’s behaviors make oral care challenging at the dentist; sensory sensitivities make oral care challenging at the dentist; child is afraid of, dislikes, or complains about three or more types of sensory stimuli encountered during dental care; their dentist is specialized in treating children with special health care needs; and child requires full assistance for toothbrushing in the home.

Why This Paper is Important to Paediatric Dentists

Although many factors contribute to challenges with oral care for children with Down syndrome, it is important that paediatric dentists consider the role sensory sensitivities may play and consider use of sensory-based interventions when appropriate.

Acknowledgements:

This work is based on research supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (U01 DE024978). The first author was also supported by the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (NCMRR K12 HD055929).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. All authors have made substantive contribution to this study and/or manuscript, and all have reviewed the final paper prior to its submission.

Contributor Information

Leah I. Stein Duker, Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy at the Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, 1540 Alcazar St, CHP 133, Los Angeles, CA, 90089..

Melissa Martinez, Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy at the Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, 1540 Alcazar St, CHP 133, Los Angeles, CA, 90089..

Christianne J. Lane, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California, 2001 N. Soto St., SSB 220X, Los Angeles, CA, 90089..

José C. Polido, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Associate Professor of Clinical Dentistry at the Ostrow School of Dentistry of the University of Southern California, 4650 Sunset Blvd, MS#116, Los Angeles, CA, 90027.

Sharon A. Cermak, Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy at the Ostrow School of Dentistry, and Professor of Pediatrics at the USC Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, 1540 Alcazar St, CHP 133, Los Angeles, CA, 90089..

References

- 1.Miller LJ, Coll JR, Schoen SA. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effectiveness of occupational therapy for children with sensory modulation disorder. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn W, Little L, Dean E, Robertson S, Evans B. The state of the science on sensory factors and their impact on daily life for children: A scoping review. OTJR. 2016;363S–26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds S, Lane SJ. Diagnostic validity of sensory over-responsivity: A review of the literature and case reports. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:516–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoen SA, Miller LJ, Flanagan J. A retrospective pre-post treatment study of occupational therapy intervention for children with sensory processing challenges. Open J Occup Ther. 2018;6:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Sasson A, Gal E, Fluss R, Katz-Zetler N, Cermak SA. Update of a meta-analysis of sensory symptoms in ASD: A new decade of research. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:4974–4996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little LM, Dean E, Tomchek S, Dunn W. Sensory Processing Patterns in Autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, and Typical Development. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2018;38:243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson K, Adams D, Alston-Knox C, Heussler HS, Keen D. Exploring the Sensory Profiles of Children on the Autism Spectrum Using the Short Sensory Profile-2 (SSP-2). J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:2069–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinclair D, Oranje B, Razak KA, Siegel SJ, Schmid S. Sensory processing in autism spectrum disorders and Fragile X syndrome — From the clinic to animal models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;76:235–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heald M, Adams D, Oliver C. Profiles of atypical sensory processing in Angelman, Cornelia de Lange and Fragile X syndromes. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020;64:117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rais M, Binder DK, Razak KA, Ethell IM. Sensory processing phenotypes in Fragile X Syndrome. ASN Neuro. 2018;10:1759091418801092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Sasson A, Soto TW, Heberle AE, Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ. Early and concurrent features of ADHD and sensory over-responsivity symptom clusters. J Atten Disord. 2017;21:835–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delgado-Lobete L, Pértega-Díaz S, Santos-del-Riego S, Montes-Montes R. Sensory processing patterns in developmental coordination disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and typical development. Res Dev Disabil. 2020;100:103608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fjeldsted B, Xue L. Sensory Processing in Young Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2019;39:553–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jirikowic TL, Thorne JC, McLaughlin SA, Waddington T, Lee A, Astley Hemingway S J. Prevalence and patterns of sensory processing behaviors in a large clinical sample of children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Res Dev Disabil. 2020;100:103617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hen-Herbst L, Jirikowic T, Hsu LY, McCoy SW. Motor performance and sensory processing behaviors among children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders compared to children with developmental coordination disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2020;103:103680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen S, Casey J. Developmental coordination disorders and sensory processing and integration: Incidence, associations and co-morbidities. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80:549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruni M, Cameron D, Dua S, Noy S. Reported sensory processing of children with Down syndrome. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2010;30:280–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Will EA, Daunhauer LA, Fidler DJ, Raitano Lee N, Rosenberg CR, Hepburn SL. Sensory processing and maladaptive behavior: Profiles within the Down syndrome phenotype. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2019;39:461–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wuang YP, Su CY. Correlations of sensory processing and visual organization ability with participation in school-aged children with Down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:2398–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Jaarsveld A, van Rooyen FC, van Biljon AM, van Rensburg IJ, James K, Böning L, Haefele L. Sensory processing, praxis and related social participation of 5–12 year old children with Down syndrome attending educational facilities in Bloemfontein, South Africa. S Afr J Occup Ther. 2016;46:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cermak SA, Stein Duker LI, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Lane CJ, Polido JC. Sensory adapted dental environments to enhance oral care for children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:2876–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein LI, Polido JC, Mailloux Z, Coleman GG, Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory sensitivities in children with autism spectrum disorders. Spec Care Dentist. 2011;31:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein LI, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35:230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein LI, Lane CJ, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Physiological and behavioral stress and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders during routine oral care. Biomed Res Int. 2014;ID 694876:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khrautieo T, Srimaneekarn N, Rirattanapong P, Smutkeeree A. Association of sensory sensitivities and toothbrushing cooperation in autism spectrum disorder. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30:505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim G, Carrico C, Ivey C, Wunsch PB. Impact of sensory adapted dental environment on children with developmental disabilities. Spec Care Dentist. 2019;39:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapiro M, Melmed RN, Sgan-Cohen HD, Parush S. Effect of sensory adaptation on anxiety of children with developmental disabilities: A new approach. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31:222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapiro M, Sgan-Cohen HD, Parush S, Melmed RN. Influence of adapted environment on the anxiety of medically treated children with developmental disability. J Pedatr. 2009;154:546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein Duker LI, Richter M, Lane CJ, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Oral care experiences and challenges for children with Down syndrome: Reports from caregivers. Pediatr Dent. 2020;42:430–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaye PL, Fiske J, Bower EJ, Newton JT, Fenlon M. Views and experiences of parents and siblings of adults with Down Syndrome regarding oral healthcare: a qualitative and quantitative study. Br Dent J. 2005;198:571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein LI, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Oral care experiences and challenges in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White BP, Mulligan S, Merrill K, Wright J. An examination of the relationships between motor and process skills and scores on the Sensory Profile. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abanto J, Ciamponi AL, Francischini E, Murakami C, de Rezende NP, Gallottini M. Medical problems and oral care of patients with Down syndrome: A literature review. Spec Care Dentist. 2011;31:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casamassimo PS, Seale NS, Ruehs K. General dentists’ perceptions of educational and treatment issues affecting access to care for children with special health care needs. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajan S, Kuriakose S, Varghese BJ, Aharaf F, Suprakasam S, Sreedevi A. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of dental practitioners in Thiruvananthapuram on oral health care for children with special needs. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2019;12:251–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Descamps I, Fernandez C, van Cleynenbreugel D, van Hoecke Y, Marks L. Dental care in children with Down syndrome: A questionnaire for Belgian dentists. Med oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24:e385–e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hugar SM, Soneta SP, Gokhale N, Badakar C, Joshi RS, Davalbhakta R. Assessment of dentist’s perception of the oral health care toward children with special healthcare needs: A cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;13:240–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrappagari D, Jung Y, Chen K. Oral health care patients with developmental disabilities: A survey of Michigan general dentists. Spec Care Dentist. 2018;38:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_behavguide.pdf Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 40.Vicari S, Bellucci S, Carlesimo GA. Visual and spatial long-term memory: differential pattern of impairments in Williams and Down syndromes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du RY, You CKY, King NM. Oral health behaviours of preschool children with autism spectrum disorders and their barriers to dental care. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson LP, Getzin A, Graham D, et al. Unmet dental needs and barriers to care for children with significant special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fisher K Is there anything to smile about: A review of oral care for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;ID 860692:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.da Rosa SV, Moysés SJ, Theis LC, Soares RC, Moysés ST, Werneck RI, Rocha JS. Barriers in access to dental services hindering the treatment of people with disabilities: A systematic review. Int J Dent. 2020;ID 9074618:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fadel HT, Baghlaf K, Ben Gassem A, Bakeer H, Alsharif AT, Kassim S. Dental students’ perceptions before and after attending a centre for children with special needs: A qualitative study on situated learning. Dent J (Basel) 2020;8:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ocanto R, Levi-Minzi MA, Chung J, Sheehan T, Padilla O, Brimlow D. The development and implementation of a training program for pediatric dentistry residents working with patients diagnosed with ASD in a special needs dental clinic. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor M Improving access to dental services for individuals with developmental disabilities: Legislative Analysis Office Report; 2018:1–34. Available at: “https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2018/3884/dental-for-developmentally-disabled-092718.pdf ”. Accessed June 8, 2021.

- 48.Waldman HB, Perlman SP, Wong A. The largest minority population in the U.S. without adequate dental care. Spec Care Dentist. 2017;37:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nightengale E, Yoon P, Wolter-Warmerdam K, Daniels D, Hickey F. Understanding hearing and hearing loss in children with Down syndrome. Am J Audiol. 2017;18:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mansoor D, Al Halabi M, Khamis AH, Kowash M. Oral health challenges facing Dubai children with autism spectrum disorder at home and in accessing oral health care. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2018;19:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]