Abstract

Oral health has been previously reported to be related with cardiovascular diseases (CVD). This study aimed to evaluate whether oral hygiene could reduce the risk of incident hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a population‐based cohort. A total of 9280 people aged 18 years or above in Guizhou province were recruited from November 20th, 2010 to December 19th, 2012. Sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyles, anthropometric measurements, oral health status and care were collected by trained interviewers. The occurrences of hypertension and T2DM were ascertained until 2020. Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the associations between oral hygiene and the occurrence of hypertension and T2DM, respectively. Compared with almost no tooth brushing, tooth brushing at least twice a day was associated with a 45% reduction (HR: .55; 95% CI: .42–.73) in hypertension events and reduced diabetes risk by 35% (HR: .65; 95% CI: .45–.94). For hypertension, those associations tended to be more pronounced in participants with Han ethic, or living in urban area, while those aged less than 60 or without baseline hypertension were more likely to have T2DM when they brush teeth less than twice a day. Frequent tooth brushing was associated with reduced risks of incident hypertension and T2DM. Tooth brushing at least twice a day may prevent future hypertension and T2DM events.

Keywords: epidemiology, hypertension, oral hygiene, tooth brushing, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

1. INTRODUCTION

Hypertension and diabetes are highly prevalent worldwide, resulting in cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and its complications. 1 , 2 About 31.1% of the world's adults have hypertension; 28.5% in high‐income countries and 31.5% in low‐ and middle‐income countries. 3 In China, a nationwide survey from 2012 to 2015 indicated that 23.2% (≈244.5 million) of Chinese adult population had hypertension and another 41.3% (≈435.3 million) had pre‐hypertension according to the Chinese guideline. 4 Increasing trend in diabetes prevalence has been demonstrated widely. 5 , 6 Diabetes currently affects more than 440 million individuals. 7 A large cross‐sectional study conducted in China (N = 170287) found that the prevalence of diabetes was 10.9%. 8 Meanwhile, over 60% participants in this study were unaware of their diagnosis of diabetes. 8 We have witnessed significant increases in prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in China during the past 30 years. 9

Poor oral health, including tooth loss and periodontal disease, is associated with increased prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. 10 , 11 Periodontal disease, including gum bleeding, gingivitis and periodontitis, may cause systemic inflammation, immunologic reactions and endothelial dysfunction, resulting in significant impacts on blood pressure (BP) and insulin resistance control. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Recently, several studies have shown that periodontal treatment is beneficial to control their BP or glucose for patients with periodontitis. 16 , 17 , 18 Microbiological plaque, the main pathogenesis in the development of periodontal disease, should be regularly and effectively cleaned from all surfaces of teeth in order to prevent periodontal disease. 19 , 20 , 21 Oral health has been previously reported to be related with CVD and this association varied by age, sex, socioeconomic status, residence, education levels, smoking, alcohol use and body mass index (BMI). 10 , 11 , 22 , 23 However, evidence on the association of oral hygiene behaviors, such as tooth brushing, with hypertension or T2DM is limited.

Guizhou Province is a multi‐ethnic area in Southwest China, with a relatively poor economy. According to data from National Bureau of Statistics, per capita disposable income of residents in Guizhou Province was 7226 RMB in 2010, which ranked 30th among 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in China. 24 As a multi‐ethnic area, Guizhou Province is also characterized by diverse cultures, multiple lifestyles and health behaviors. 25 It has been reported that the epidemiology of hypertension and T2DM is different in various geographical areas of China. 4 , 7 There are higher incidences of hypertension/T2DM but lower quality of related health care in Southwest regions, especially in rural areas. 26 Previous research on the association between oral hygiene and hypertension/T2DM has mainly focused on high‐income developed countries, 11 , 27 but it may differ from middle‐income and low‐income countries where dental care is paid less attention. In this large cohort study in Guizhou Province, we investigated the relationship between oral health and incident hypertension/T2DM.

2. MATERIAL AND METHOD

2.1. Population

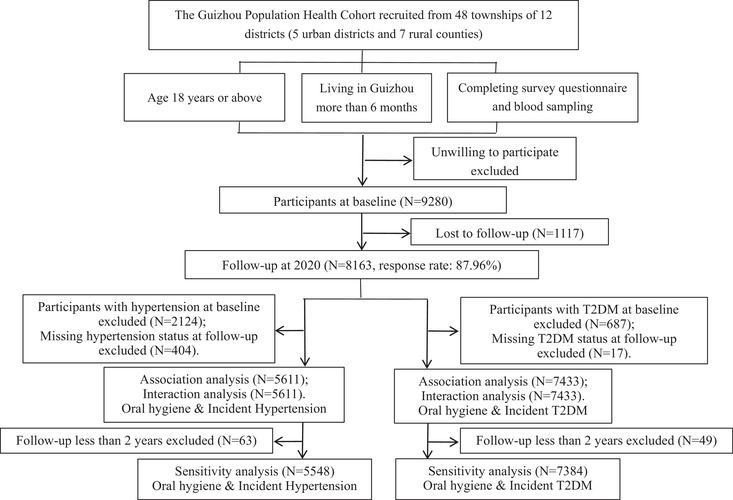

The Guizhou Population Health Cohort Study (GPHCS) was conducted in Southwest China during 2010–2020. Based on the multistage proportional stratified cluster sampling method, a total of 9280 people from 48 townships of 12 districts (five urban districts and seven rural counties) in Guizhou province were recruited at baseline November 20, 2010 to December 19, 2012, including 4442 males and 4838 females. The inclusion criteria were residents who were: (1) age 18 years or above; (2) living in the study regions for more than 6 months and having no plan to move out; (3) completing survey questionnaire and blood sampling. Residents who did not sign the written informed consent were excluded. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guizhou Province Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (No.S2017‐02).

A structured questionnaire was used to collect the baseline information on sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyles, oral health status and oral hygiene care by trained interviewers during the baseline via a face‐to‐face interview. Participants also received physical examination by trained physicians and provided samples of blood. All deaths were confirmed through the Death Registration Information System and Basic Public Health Service System. Each participant was followed up until the first occurrence of the corresponding outcome, or loss to follow‐up, which occurred first prior to December 31, 2020. And we followed up 8163 participants, representing a follow‐up rate of 87.96%. We further excluded 24 participants with missing data on frequency of tooth brushing and included the remaining 8139 participants in the analysis of baseline characteristics. Furthermore, participants with hypertension at baseline (N = 2124) or missing hypertension status at follow‐up (N = 404) were excluded, leaving 5611 participants eligible for the analysis of the association between hypertension incidence and oral hygiene. Meanwhile, participants with T2DM at baseline (N = 687) or missing T2DM status at follow‐up (N = 19) were excluded, and the remaining 7433 participants were used to analyze the association between T2DM incidence and oral hygiene. The flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart

2.2. Oral hygiene assessment

Information on oral hygiene was collected by the structured questionnaire, including frequency of tooth brushing (never, <1 time per day, 1 time per day, and ≥2 times per day), gum bleeding (never, sometimes, and always), number of permanent teeth, regular dental visits (<1 and ≥1 time a year), and professional dental cleaning (<1 and ≥1 time a year). Considering the distribution of data, we categorized the loss of permanent teeth into two categories: yes versus no.

2.3. Definitions of hypertension (HTN) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

According to the 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension, hypertension was defined as one of the following conditions: (1) systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg; (2) use of anti‐hypertensive medication or self‐reported physician diagnosis of hypertension. 28

According to the American Diabetes Association criteria, T2DM was defined as one of the following conditions: (1) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥7.0 mmol/L; (2) oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥11.1 mmol/L; (3) hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥6.5%; (4) receiving hypoglycemic treatment or self‐reported physician diagnosis of T2DM. 29

2.4. Other covariates of Interest

Age, sex, ethic group (Han, others), location (urban, rural), marriage (married, unmarried, and others), occupation (farmers, other occupation, and unemployed or retired) were ascertained and educational level was categorized as no formal education, primary school (1–6 years), junior high school (7–9 years), senior school and above (10 years and above). Smoking habit (never smoked, current smoker and past smoker), alcohol use (nondrinker, drinker) and sports (yes, no [daily sports time less than 10 min/day]) was ascertained. Baseline height, weight, SBP, and DBP were obtained. BP was measured three times on the right arm positioned at heart level after the participant was sitting at rest for 5 min, with 30 s between each measurement. The average of the three readings was used for analysis if the difference between the three measurements is no more than 10 mmHg; the average value of the two similar measurements was taken as the final reading if there is a large difference between the three measurements; the observed value was taken as the final reading directly if BP was measured only once. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Plasma glucose, serum triglyceride (TG), high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C), and total cholesterol (TC) were also measured. The 2016 Chinese Guideline for the Management of Dyslipidemia in Adults (Chinese guideline) was used to define dyslipidemia as one of the following conditions: (1) TC ≥6.22 mmol/L; (2) TG ≥2.26 mmol/L; (3) HDL‐C < 1.04 mmol/L; (4) LDL‐C ≥4.14 mmol/L; (5) treatment for blood lipid reduction or self‐reported medical diagnosis of dyslipidemia. 30

2.5. Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were presented and compared among participants with different frequency of teeth brushing. Person‐years of follow‐up for each participant were calculated from the date of enrollment to the end date, which was defined as the date of incident hypertension/T2DM or follow‐up, whichever occurred first. The relevant incidence density in total and subgroup participants were then calculated by dividing the number of patients with outcome events by the corresponding sum of person‐years.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the associations between oral hygiene and the occurrence of hypertension and T2DM, respectively. Proportional hazards assumption was tested by plotting the survival graph in different groups and was not violated. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. For oral hygiene, we included the frequency of tooth brushing both categorically and continuously. Multivariable regression models were constructed with adjustment for (1) age (continuous variable) and sex; (2) age (continuous variable), sex, ethic group, location, occupation, marriage, education levels, smoking habit, alcohol use, sports and BMI (continuous variable); and (3) variables listed above, as well as for baseline hypertension, T2DM, and dyslipidemia.

We performed the analyses by excluding participants followed‐up for less than 2 years for sensitivity analysis. Subgroup analyses were also conducted to assess the potential effect modification on the association of tooth brushing frequency (<2 times/day, ≥2 times/day) with hypertension and T2DM, including location (urban, rural), age (<60 years, ≥60 years), sex, ethic group (Hanzu, others), BMI (<18.5 kg/m2, 18.5∼23.9 kg/m2, 24.0∼27.9 kg/m2, and ≥28 kg/m2), baseline hypertension (no, yes), baseline T2DM (no, yes), baseline dyslipidemia (no, yes) and gum bleeding (never, sometimes, and always). Results were considered significant when two‐tailed ɑ was .05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics (Table 1)

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total | Frequency of tooth brushing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (N = 8139) | 0/d (n = 456) | <1/d (n = 596) | 1/d (n = 4819) | > = 2/d (n = 2268) | p |

| Rural, % | 5421 (66.6) | 344 (75.4) | 427 (71.6) | 3402 (70.6) | 1248 (55.0) | <.001 |

| Age at baseline, years | 44.52 ± 15.16 | 61.61 ± 14.18 | 51.63 ± 14.09 | 44.07 ± 14.16 | 40.12 ± 14.64 | <.001 |

| Male, % | 3862 (47.5) | 239 (52.4) | 309 (51.8) | 2360 (49.0) | 954 (42.1) | <.001 |

| Hanzu, % | 4778 (58.7) | 254 (55.7) | 331 (55.5) | 2741 (56.9) | 1452 (64.0) | <.001 |

| Marriage, % | <.001 | |||||

| Married | 6538 (80.3) | 349 (76.5) | 508 (85.2) | 4020 (83.4) | 1661 (73.2) | |

| Unmarried | 771 (9.5) | 13 (2.9) | 19 (3.2) | 353 (7.3) | 386 (17.0) | |

| Others | 830 (10.2) | 94 (20.6) | 69 (11.6) | 446 (9.3) | 221 (9.7) | |

| Occupation, % | <.001 | |||||

| Farmer | 4639 (57.0) | 323 (70.8) | 478 (80.2) | 3054 (63.4) | 784 (34.6) | |

| Other | 2262 (27.8) | 38 (8.3) | 79 (13.3) | 1143 (23.7) | 1002 (44.2) | |

| Unemployed or retired | 1238 (15.2) | 95 (20.8) | 39 (6.5) | 622 (12.9) | 482 (21.3) | |

| Education, % | <.001 | |||||

| None | 1683 (20.7) | 277 (60.7) | 251 (42.1) | 986 (20.5) | 169 (7.5) | |

| 1–6 years | 2981 (36.6) | 140 (30.7) | 272 (45.6) | 2015 (41.8) | 554 (24.4) | |

| 7–9 years | 2400 (29.5) | 33 (7.2) | 66 (11.1) | 1438 (29.8) | 863 (38.1) | |

| 10 years and above | 1075 (13.2) | 6 (1.3) | 7 (1.2) | 380 (7.9) | 682 (30.1) | |

| Lifestyle | ||||||

| Smoking habit, % | <.001 | |||||

| Current smoker | 2328 (28.6) | 159 (34.9) | 214 (35.9) | 1411 (29.3) | 544 (24.0) | |

| Past smoker | 218 (2.7) | 13 (2.9) | 16 (2.7) | 124 (2.6) | 65 (2.9) | |

| Never smoked | 5593 (68.7) | 284 (62.3) | 366 (61.4) | 3284 (68.1) | 1659 (73.1) | |

| Alcohol use, % | 2617 (32.2) | 151 (33.1) | 235 (39.4) | 1475 (30.6) | 756 (33.3) | <.001 |

| Sports (10 min/day and more), % | 7077 (87.0) | 368 (80.7) | 554 (93.0) | 4184 (86.8) | 1971 (86.9) | <.001 |

| Anthropometric measurements | ||||||

| BMI a , kg/m2 | 22.88 ± 3.35 | 21.81 ± 3.24 | 22.69 ± 3.17 | 22.9 ± 3.34 | 23.09 ± 3.39 | <.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 125.47 ± 21.15 | 134.43 ± 23.7 | 128.72 ± 21.74 | 125.5 ± 20.92 | 122.76 ± 20.29 | <.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 78.37 ± 11.96 | 80.59 ± 12.47 | 79.28 ± 11.65 | 78.25 ± 12.01 | 77.95 ± 11.79 | <.001 |

| Comorbity | ||||||

| HTN | 2124 (26.1) | 191 (41.9) | 184 (30.9) | 1214 (25.2) | 535 (23.6) | <.001 |

| T2DM | 687 (8.4) | 50 (11.0) | 57 (9.6) | 355 (7.4) | 225 (9.9) | <.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 4694 (57.7) | 214 (46.9) | 322 (54.0) | 2697 (56.0) | 1461 (64.4) | <.001 |

| Oral health status | ||||||

| No loss of teeth b , % | 6081 (74.7) | 250 (54.8) | 364 (61.1) | 3709 (77.0) | 1758 (77.5) | <.001 |

| Gum bleeding c , % | <.001 | |||||

| Never | 5597 (68.8) | 404 (88.6) | 420 (70.5) | 3333 (69.2) | 1440 (63.5) | |

| Sometimes | 2282 (28.0) | 46 (10.1) | 163 (27.3) | 1341 (27.8) | 732 (32.3) | |

| Always | 251 (3.1) | 6 (1.3) | 12 (2.0) | 140 (2.9) | 93 (4.1) | |

| Oral hygiene care | ||||||

| Dental visit for any reasons d , % | 331 (4.1) | 16 (3.6) | 18 (3.1) | 154 (3.2) | 143 (6.5) | <.001 |

| Deatal visit for professional cleaning e , %△ | 85 (1.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (.2) | 31 (.6) | 53 (2.4) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HTN, hypertension; SBP, systolic blood pressur; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

In total, aBMI was missing for eight participants, bno loss of teeth was missing for 91 participants, cgum bleeding was missing for nine participants, ddental visit for any reasons was missing for 169 participants and edeatal visit for professional cleaning was missing for 104 participants.

Of the 8139 participants in the GPHCS, 12.92 % (1052/8139) did not regularly brush teeth, and 27.86% (2268/8139) brushed their teeth more than once. The average age of the study participants was 44.52 years. Among all the participants, 47.5% were female, 66.6% were rural residents, and 58.7% were Han race. The means of BMI, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure were 22.88 kg/m2 (SD 3.35), 125.47 mmHg (SD 21.15), and 78.37 mmHg (SD 11.96), respectively. Compared with those regularly brush teeth (≥1/d), participants brush teeth less than once per day were more likely to be older, living in rural area, less educated, and current smokers. 31.1%, 4.1%, and 25.3% of the participants reported gum bleeding, at least one dental visit per year, and one or more loss of teeth, respectively.

3.2. The association between oral hygiene and incident hypertension (Table 2)

TABLE 2.

The association between oral hygiene and incident hypertension

| Incident density/1000 PYs | Unadjusted Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases/n | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | ||

| Gum bleeding | .028 | .348 | .411 | .581 | ||||||

| Never | 854/3790 | 31.67 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Sometimes | 322/1637 | 27.09 | .83 (.73, .95)** | .90 (.79, 1.03) | .93 (.81, 1.06) | .93 (.81, 1.06) | ||||

| Always | 39/179 | 31.02 | .99 (.72, 1.36) | 1.09 (.79, 1.50) | 1.02 (.74, 1.41) | 1.02 (.74, 1.41) | ||||

| Tooth integrity | <.001 | .275 | .072 | .075 | ||||||

| Complete | 911/4316 | 29.24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Incomplete | 286/1231 | 28.68 | 1.30 (1.13, 1.48)*** | .92 (.8, 1.07) | .88 (.76, 1.01) | .88 (.76, 1.01) | ||||

| Frequency of tooth brush (times/day) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 93/255 | 55.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <1 | 100/387 | 37.48 | .64 (.48, .86)** | .89 (.67, 1.19) | .80 (.60, 1.08) | .80 (.59, 1.08) | ||||

| 1 | 769/3361 | 32.22 | .47 (.37, .58)*** | .81 (.64, 1.02) | .77 (.60, .97)* | .77 (.60, .98)* | ||||

| ≥2 | 253/1608 | 21.19 | .29 (.23, .37)*** | .58 (.44, .75)*** | .54 (.41, .71)*** | .55 (.42, .73)*** | ||||

| Dental visit for any reasons | .986 | .562 | .405 | .660 | ||||||

| <1/year | 45/219 | 29.51 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| ≥1/year | 1147/5273 | 30.40 | 1.00 (.74, 1.35) | 1.09 (.81, 1.48) | 1.14 (.84, 1.54) | 1.07 (.79, 1.45) | ||||

Note: Model1 was adjusted for age (continuous variable), sex; Model2 was adjusted for the variables listed in the Model1 as well as location, ethic group, marriage, occupation, education, smoking status, alcohol use, sport and BMI (kg/m2); Model3 was adjusted for the variables listed in the Model2 as well as baseline T2DM, and dyslipidemia.

Cases: The number of incident hypertension in participants in the corresponding subgroup.

n: The number of participants in the corresponding subgroup.

Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PYs, person‐years.

p < .05, **p < .01., ***p < .001.

During a median follow‐up of 6.59 years, 1215 incident hypertension cases were identified (incidence density of 31.00/1000 PYs). After the adjustment for potential confounders, brushing teeth once a day was associated with a 23% reduction in risk of hypertension (HR: .77; 95% CI: .60–.98; p < .05), while brushing teeth at least twice a day was associated with a 45% reduction (HR: .55; 95% CI: .42–.73; p < .001). Although participants brushed teeth less than once did not appear to convey significant benefit from tooth brushing in the multivariate analysis (HR: .80, 95% CI: .59–1.08), a potential dose‐response association of frequency of tooth brushing with hypertension was observed (P‐trend: < .001).

3.3. The association between oral hygiene and incident T2DM (Table 3)

TABLE 3.

The association between oral hygiene and incident T2DM

| Incident density/1000 PYs | Unadjusted Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral hygiene | Cases/n | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | HR (95%CI) | P‐trend | |

| Gum bleeding | ||||||||||

| Never | 561/5100 | 15.15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Sometimes | 176/2097 | 11.06 | .72 (.60, .85)*** | .008 | .76 (.64, .91)** | .062 | .78 (.65, .95)** | .080 | .82 (.66, 1.01) | .099 |

| Always | 28/228 | 16.74 | 1.09 (.74, 1.61) | 1.20 (.82, 1.77) | 1.15 (.78, 1.7) | 1.15 (.78, 1.72) | ||||

| Tooth integrity | ||||||||||

| Complete | 571/5607 | 13.70 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Incomplete | 189/1746 | 15.25 | 1.25 (1.05, 1.47)* | .011 | .98 (.82, 1.17) | .818 | .97 (.81, 1.16) | .730 | .97 (.81, 1.17) | .771 |

| Frequency of tooth brush (times/day) | ||||||||||

| 0 | 52/405 | 18.91 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <1 | 71/538 | 18.94 | .96 (.67, 1.39) | <.001 | 1.17 (.81, 1.69) | <.001 | 1.13 (.78, 1.64) | .001 | 1.12 (.76, 1.64) | .002 |

| 1 | 489/4453 | 14.88 | .63 (.47, .85)** | .88 (.65, 1.19) | .91 (.67, 1.25) | .94 (.68, 1.29) | ||||

| ≥2 | 155/2037 | 10.20 | .40 (.29, .56)*** | .62 (.44, .87)** | .63 (.44, .91)* | .65 (.45, .94)* | ||||

| Dental visit for any reasons | ||||||||||

| <1/year | 28/279 | 13.58 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1/year | 723/7002 | 14.03 | 1.02 (.69, 1.50) | .941 | 1.07 (.72, 1.58) | .748 | 1.12 (.76, 1.67) | .562 | 1.01 (.84, 1.21) | .927 |

Note: Model1 was adjusted for age (continuous variable), sex; Model2 was adjusted for the variables listed in the Model1 as well as location, ethic group, marriage, occupation, education, smoking status, alcohol use, sport and BMI (kg/m2); Model3 was adjusted for the variables listed in the Model2 as well as baseline hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Cases: The number of incident T2DM in participants in the corresponding subgroup.

n: The number of participants in the corresponding subgroup.

Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PYs, person‐years.

p < .05, **p < .01., ***p < .001.

We identified 767 T2DM cases during the follow‐up and the incidence density was 14.61/1000 person‐years. After adjustment for age, sex, location, ethic group, marriage, occupation, education, smoking status, alcohol use, sport, BMI, baseline hypertension and dyslipidemia, more times of tooth brushing per day was related to significantly decreased risk of T2DM (P‐trend = .002). The multivariable‐adjusted HR for diabetes was .65 (95% CI: .45–.94) for two and more times tooth brushing per day, as compared with those never brushed. No significant associations were found for gum bleeding and dental integrity with either hypertension or T2DM after the adjustment.

3.4. Sensitivity analyses (Table 4)

TABLE 4.

Sensitivity analyses

| Hypertension | Diabetes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral hygiene | Cases/n | Incident density/1000 PYs | aHR (95%CI) | Cases/n | Incident density/1000 PYs | aHR (95%CI) |

| Gum bleeding | ||||||

| Never | 818/3746 | 30.39 | 1 | 540/5063 | 14.71 | 1 |

| Sometimes | 307/1619 | 25.85 | .93 (.81, 1.07) | 168/2085 | 10.53 | .83 (.64, 1.04) |

| Always | 38/178 | 30.26 | 1.06 (.76, 1.47) | 28/228 | 16.74 | 1.20 (.80, 1.78) |

| Tooth integrity | ||||||

| Complete | 874/4275 | 28.04 | 1 | 554/5584 | 13.38 | 1 |

| Incomplete | 273/1213 | 32.10 | .89 (.76, 1.03) | 177/1723 | 14.35 | .94 (.78, 1.14) |

| Frequency of tooth brush (times/day) | ||||||

| 0 | 87/245 | 52.38 | 1 | 49/393 | 18.24 | 1 |

| <1 | 94/380 | 35.26 | .79 (.58, 1.08) | 66/532 | 17.58 | 1.07 (.72, 1.59) |

| 1 | 738/3324 | 30.95 | .76 (.59, .98)* | 477/4431 | 14.60 | .95 (.69, 1.31) |

| ≥2 | 244/1599 | 20.43 | .54 (.40, .72)*** | 146/2028 | 9.66 | .64 (.44, .93)* |

| Dental visit for any reasons | ||||||

| <1/year | 42/213 | 27.63 | 1 | 25/272 | 12.58 | 1 |

| ≥1/year | 1098/5217 | 29.15 | 1.10 (.81, 1.52) | 698/6964 | 5.53 | 1.12 (.74, 1.68) |

Note: Adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) adjusted for age (continuous variable), sex, location, ethic group, marriage, occupation, education, smoking status, alcohol use, sport and BMI (kg/m2), baseline hypertension, T2DM, and dyslipidemia; outcome factors were not included.

Cases: The number of outcome events in participants with more than 2 years of follow‐up in the corresponding subgroup.

n: The number of participants with more than 2 years of follow‐up in the corresponding subgroup.

Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PYs, person‐years.

p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The associations between oral hygiene and incident hypertension/T2DM remained when participants with less than 2 years of follow‐up were excluded. Compared with those never brushed, participants in the frequency of two and more times per day had an 0.54 (95% CI: .40–.72; p< .001) times decreased risk of hypertension, and adjusted 0.64 (95% CI: .44–.93; p< .001) times decreased risk of diabetes.

3.5. Interaction analyses (Table 5)

TABLE 5.

Interaction between frequency of tooth brush and basic information on the incidence of hypertension and T2DM

| Hypertension | T2DM | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Cases/n | Incident density/1000 PYs | HR(95%CI) | Pfor interaction | Cases/n | Incident density/1000 PYs | HR(95%CI) | Pfor interaction |

| Location | ||||||||

| Urban | 282/1130 | 37.31 | 1.89 (1.42,2.52)*** | <0.001 | 165/1619 | 14.92 | 1.43 (1.01,2.03)* | 0.175 |

| Rural | 680/2873 | 32.88 | 1.14 (0.95,1.37) | 447/3777 | 15.80 | 1.38 (1.08,1.77)* | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| <60 | 754/3443 | 30.74 | 1.47 (1.25,1.74)*** | 0.486 | 477/4396 | 14.85 | 1.62 (1.30,2.03)*** | 0.013 |

| 60‐ | 208/560 | 56.37 | 1.35 (0.86,2.13) | 135/1000 | 18.78 | 0.90 (0.57,1.43) | ||

| Ethic Group | ||||||||

| Han | 581/2229 | 36.38 | 1.53 (1.25,1.88)*** | <0.001 | 394/3082 | 17.50 | 1.55 (1.21,2.00)** | 0.067 |

| Others | 381/1774 | 31.05 | 1.18 (0.93,1.50) | 218/2314 | 12.93 | 1.19 (0.85,1.67) | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 477/1917 | 35.43 | 1.41 (1.12,1.76)** | 0.509 | 303/2641 | 15.66 | 1.43 (1.08,1.91)* | 0.474 |

| Female | 485/2086 | 32.73 | 1.42 (1.14,1.77)** | 309/2755 | 15.45 | 1.42 (1.07,1.89)* | ||

| BMI | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 52/262 | 27.75 | 1.30 (0.65,2.62) | 0.097 | 30/330 | 12.76 | 1.02 (0.41,2.51) | 0.290 |

| 24‐ | 636/2689 | 33.33 | 1.58 (1.27,1.95)*** | 358/3499 | 14.18 | 1.52 (1.14,2.03)** | ||

| 28‐ | 219/865 | 36.49 | 1.36 (1.02,1.80)* | 152/1235 | 16.17 | 1.54 (1.06,2.25)* | ||

| >28 | 54/182 | 42.13 | 0.80 (0.47,1.38) | 70/326 | 30.31 | 1.16 (0.69,1.96) | ||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| No | / | / | / | / | 438/4015 | 14.92 | 1.73 (1.35,2.22)*** | 0.001 |

| Yes | / | / | / | / | 174/1381 | 17.44 | 0.97 (0.68,1.39) | |

| T2DM | ||||||||

| No | 895/3744 | 33.87 | 1.46 (1.24,1.72)*** | 0.158 | / | / | / | / |

| Yes | 60/239 | 34.94 | 1.03 (0.59,1.80) | / | / | / | / | |

Note: The models were adjusted for age (continuous variable), sex, ethic group, location, education, marriage, occupation, smoking habit, BMI (kg/m2), baseline hypertension, T2DM, and dyslipidemia; outcome factors were not included.

Cases: The number of outcome events in participants who brushed their teeth less than 2 times per day in the corresponding subgroup.

n: The number of participants who brushed their teeth less than 2 times per day in the corresponding subgroup.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; PYs, person‐years.

* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001

The inverse association between frequency of tooth brushing (<2 times/day, ≥2 times/day) and hypertension did not differ significantly by sex, BMI, and baseline T2DM, while those associations tended to be more pronounced in participants with Han ethic, or living in urban area. For T2DM, however, those aged less than 60 or without baseline hypertension were more likely to have T2DM during the follow‐up.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that lower frequency of daily tooth brushing was associated with higher hypertension risk, as well as higher T2DM risk. The advantage of tooth brushing to prevent hypertension and T2DM was independent of potential confounders (age, sex, lifestyle, etc.). Compared with almost no tooth brushing, tooth brushing at least twice a day was associated with 45% reduction in hypertension and 35% in T2DM risk. This study suggests that oral behavioral change in tooth brushing may decrease the incidence of hypertension and T2DM. But no significant associations were found for gum bleeding and dental integrity.

Our findings that low frequency of tooth brushing may be a risk factor of hypertension and T2DM were in accordance with some previous studies. 11 , 18 , 31 A recent meta‐analysis (one cohort study, 14 case‐control studies, and five cross‐sectional studies) reported that the lowest frequency of tooth brushing was significantly associated with an increased risk of diabetes (OR:1.32; 95% CI: 1.19–1.47) compared with the highest frequency. 27 An intervention study in Japan (N = 182) showed a significant improvement of tooth brushing frequency and systolic blood pressure in the intervention group (dental health education group) compared with the non‐intervention group. 21 Regarding to other oral behaviors, only about 1.0% and 4.1% subjects in this study reported professional cleaning and dental visits, respectively, which were much lower than that in Korea (25.9% and 44.3%). 23

Several observational studies have reported that oral health status, such as gum bleeding and tooth loss, were associated with hypertension and diabetes. Patients with diabetes had a higher level of tooth loss than those without diabetes, and few studies demonstrated that tooth loss was a risk factor for diabetes. 32 , 33 However, no associations were detected between tooth loss and T2DM in this cohort study, which was possibly due to the differences in characteristics of the subjects and diagnostic criterion of diabetes among different studies. In addition, some cross‐sectional surveys also demonstrated that patients with hypertension had lost more teeth than those without hypertension, 34 , 35 but almost no study observed the effect of tooth loss on hypertension risk in prospective settings, which was in line with our finding. Besides, a prospective study in Japan observed an association between periodontal disease and hypertension in young adults, 36 and a 13‐year cohort study in South Korea provided similar evidence in elderly participants. 37 However, gum bleeding, an early sign of periodontal disease, 38 was not related to hypertension incidence in our study, which was likely resulted from the self‐report measurement and the difference of oral inflammation severity.

The novelty of our study was that we provided stronger evidence that regular tooth brushing may prevent future hypertension and T2DM events through a 10‐year follow‐up in a developing country with a population‐based sample. One or more times tooth brushing per day can reduce the risk of hypertension, while the benefit for preventing diabetes needs least twice a day. This notable benefit might be explained as the following mechanisms. First, harmful bacteria of periodontal disease causes inflammatory response and activates cytokines, increasing plasma levels of inflammatory markers, such as C‐reactive protein (CRP), TNF‐a and IL‐6. 39 And these inflammatory markers may impair intracellular insulin signaling, 13 , 40 leading to insulin resistance which is an important risk factor for diabetes and hypertension. 41 , 42 , 43 Second, low frequency of tooth brushing boosted the proliferation of Porphyromonas gingivalis, producing a worse enteric environment and increasing insulin resistance. 44 Third, tooth brushing is effective for cleaning plaque that is the initiating factor and the main pathogenic factor of periodontal disease, 45 , 46 which means that tooth brushing may decrease the risk of periodontal disease and keep gingival health. 19

The subgroup analysis suggested that those with Han ethic, and living in rural areas would have a greater benefit for hypertension prevention with an improvement in toothbrushing frequency. So as to T2DM, no regular tooth brushing had more remarkable risk for those aged less than 60 years, and without hypertension. Therefore, early intervention on oral hygiene in these subgroups is of vital importance, which might bring large benefits to the lower risk of hypertension and T2DM.

To our knowledge, this is the first report on tooth brushing in association with hypertension and T2DM in multinational region in Southwest China. The strengths of our study include the population‐based prospective design, large sample size, long duration and high response rate for follow‐up survey. Information was available for a wide range of lifestyles and potential confounding factors.

4.1. Limitations

Some limitations in this study should be concerned. As with many large‐scale epidemiologic studies, in our study, self‐reports were used for oral health assessment. The misclassification bias might originate from self‐perceived frequency of tooth brushing and forgotten number of tooth loss, which could have let to an underestimation of the associations. Moreover, the current analysis examined only oral health behaviors assessed as baseline; changes in oral hygiene habit over time were not taken into account.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study suggested that frequent tooth brushing was associated with a reduced risk of hypertension and diabetes incidences. Tooth brushing at least twice a day may prevent future hypertension and diabetes events.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Na Wang, Tao Liu, and Chaowei Fu designed the study. Yiying Wang, Lisha Yu and Jie Zhou were involved in data collection and assembly; and Tao Liu supervised this process. Yiying Wang, Yizhou Jiang and Yun Chen analyzed the data; Yizhou Jiang and Na Wang interpreted the data; while Na Wang and Chaowei Fu supervised the conduct of data analysis and interpretation. Yiying Wang and Yizhou Jiang drafted the manuscript as co‐first authors; Na Wang, Tao Liu, and Chaowei Fu reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors took part in critical revision and approved the final draft.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Guizhou Province Science and Technology Support Program (Qiankehe [2018]2819).

Wang Y, Jiang Y, Chen Y, et al. Associations of oral hygiene with incident hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A population based cohort study in Southwest China. J Clin Hypertens. 2022;24:483–492. 10.1111/jch.14451

Contributor Information

Na Wang, Email: na.wang@fudan.edu.cn.

Tao Liu, Email: liutaombs@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hajjar I, Kotchen JM, Kotchen TA. Hypertension: trends in prevalence, incidence, and control. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006; 27: 465‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018; 20(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population‐based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016; 134(6): 441‐450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, et al. Status of hypertension in china: results from the china hypertension survey, 2012–2015. Circulation. 2018; 137(22): 2344‐2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ, et al. Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia. 2019; 62(1): 3‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Magliano DJ, Islam RM, Barr ELM, et al. Trends in incidence of total or type 2 diabetes: systematic review. BMJ. 2019: 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma RCW. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetic complications in China. Diabetologia. 2018; 61(6): 1249‐1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA. 2017; 317: 2515‐2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weng J, Ji L, Jia W, et al. Standards of care for type 2 diabetes in China. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016; 32: 442‐458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Del Pinto R, Pietropaoli D, Munoz‐Aguilera E, et al. Periodontitis and hypertension: is the association causal?. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev; 2020: 27(4): 281‐289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fujita M, Ueno K, Hata A. Lower frequency of daily teeth brushing is related to high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2009; 234(4): 387‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu DY, Hong X, Li X. Oral health in China–trends and challenges. Int J Oral Sci. 2011; 3(1): 7‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tilg H, Moschen AR. Inflammatory mechanisms in the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol Med. 2008; 14(3‐4): 222‐231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schenkein HA, Loos BG. Inflammatory mechanisms linking periodontal diseases to cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Periodontol J Periodontol. 2013; 84: S51‐S69. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsui S, Kajikawa M, Maruhashi T, et al. Decreased frequency and duration of tooth brushing is a risk factor for endothelial dysfunction. Int J Cardiol. 2017; 241: 30‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsakos G, Sabbah W, Hingorani AD, et al. Is periodontal inflammation associated with raised blood pressure? Evidence from a National US survey. J Hypertens. 2010; 28: 2386‐2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baeza M, Morales A, Cisterna C, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment in patients with periodontitis and diabetes: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Appl Oral Sci. 2020; 28: e20190248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Song TJ, Chang Y, Jeon J, et al. Oral health and longitudinal changes in fasting glucose levels: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2021; 16(6): e0253769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCracken GI, Heasman L, Stacey F, et al. A clinical comparison of an oscillating/rotating powered toothbrush and a manual toothbrush in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2004; 31(9): 805‐812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chapple IL, Van der Weijden F, Doerfer C, et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: managing gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015; 42(16): S71‐S76. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamazaki Y, Morita T, Nakai K, et al. Impact of dental health intervention on cardiovascular metabolic risk: a pilot study of Japanese adults. J Hum Hypertens. 2021. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi HM, Han K, Park YG, et al. Associations among oral hygiene behavior and hypertension prevalence and control: the 2008 to 2010 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2015; 86(7): 866‐873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park SY, Kim SH, Kang SH, et al. Improved oral hygiene care attenuates the cardiovascular risk of oral health disease: a population‐based study from Korea. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40(14): 1138‐1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Bureau of Statistics . http://https–data–stats–gov–cn.proxy.www.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=E0103 Accessed January 26, 2022.

- 25. Nie F, Wang Z, Zeng Q, et al. Health behaviors and metabolic risk factors are associated with dyslipidemia in ethnic Miao Chinese adults: the China multi‐ethnic cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li X, Krumholz HM, Yip W, et al. Quality of primary health care in China: challenges and recommendations. Lancet. 2020; 395(10239): 1802‐1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fu W, Lv C, Zou L, et al. Meta‐analysis on the association between the frequency of tooth brushing and diabetes mellitus risk. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019; 35(5): e3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu LS, Writing Group of 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension . 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011; 39(7): 579‐615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. American Diabetes Association (ADA) . Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes‐2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S13‐S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Joint committee issued Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in adults . 2016 Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2016;44(10):833‐853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kajikawa M, Nakashima A, Maruhashi T, et al. Poor oral health, that is, decreased frequency of tooth brushing, is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Circ J. 2014; 78(4): 950‐954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suzuki S, Noda T, Nishioka Y, et al. Evaluation of tooth loss among patients with diabetes mellitus using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan. Int Dent J. 2020; 70(4): 308‐315. Aug. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luo H, Pan W, Sloan F, et al. Forty‐year trends in tooth loss among american adults with and without diabetes mellitus: an age‐period‐cohort analysis. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015; 12: E211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mendes JJ, Viana J, Cruz F, et al. Blood pressure and tooth loss: a large cross‐sectional study with age mediation analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Da D, Wang F, Zhang H, et al. Association between tooth loss and hypertension among older Chinese adults: a community‐based study. BMC Oral Health. 2019; 19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kawabata Y, Ekuni D, Miyai H, et al. Relationship between prehypertension/hypertension and periodontal disease: a prospective cohort study. Am J Hypertens. 2016; 29(3): 388‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JH, Jeong SN. A Population‐based study on the association between periodontal disease and major lifestyle‐related comorbidities in South Korea: an elderly cohort study from 2002–2015. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020; 56(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lang NP, Joss A, Orsanic T, et al. Bleeding on probing. A predictor for the progression of periodontal disease?. J Clin Periodontol. 1986; 13(6): 590‐596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Teeuw WJ, Slot DE, Susanto H, et al. Treatment of periodontitis improves the atherosclerotic profile: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2014; 41(1): 70‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pischon N, Heng N, Bernimoulin JP, et al. Obesity, inflammation, and periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2007; 86(5): 400‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, et al. C‐reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001; 286(3): 327‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sesso HD, Buring JE, Rifai N, et al. C‐reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. JAMA. 2003; 290(22): 2945‐2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sesso HD, Wang L, Buring JE, et al. Comparison of interleukin‐6 and C‐reactive protein for the risk of developing hypertension in women. Hypertension. 2007; 49(2): 304‐310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuwabara M, Motoki Y, Ichiura K, et al. Association between toothbrushing and risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a large‐scale, cross‐sectional Japanese study. BMJ Open. 2016; 6(1): e009870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lang T, Staufer S, Jennes B, et al. Clinical validation of robot simulation of toothbrushing–comparative plaque removal efficacy. BMC Oral Health. 2014: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vajawat M, Deepika PC, Kumar V, et al. A clinicomicrobiological study to evaluate the efficacy of manual and powered toothbrushes among autistic patients. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015; 6(4): 500‐504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]