Highlights

-

•

Physical treatment with enzymes effectively modified soluble dietary fiber (SDF).

-

•

Twin-screw extrusion assisted with enzyme reached the highest extraction yield.

-

•

The physicochemical properties of modified SDF were improved.

-

•

Modified SDF possessed a better antioxidant activity.

Keywords: Corn bran, Soluble dietary fiber, Twin-screw extrusion, Ultrasonic treatment, Enzyme hydrolysis

Abstract

Soluble dietary fiber (SDF), which is a component of dietary fibers exhibit many physiological functions, biological activity, and good gel forming ability. In this study, extraction of SDF from corn bran was evaluated using twin-screw extrusion and ultrasonic treatment and the combinations of the respective methods with dual enzyme hydrolysis. The monosaccharide compositions, molecular weight, physicochemical properties, and structural and functional characteristics were determined. The results showed that ultrasonic and twin-extrusion treatments significantly increased the SDF content from 2.42 to 4.58 and 6.54%, respectively. Dual enzyme hydrolysis further increased the SDF content. Modification treatment changed the monosaccharide composition, improved physicochemical and functional properties, such as water and oil holding capacity, nitrite adsorption, and antioxidative ability. In conclusion, physical modification combined with enzyme treatment distinctly improved the extraction yield, physicochemical and functional properties of SDF. Therefore, the modified SDF is suitable as a functional food additive.

1. Introduction

Dietary fibers are carbohydrate polymers widely present in the cell walls of grains, vegetables, and fruits. In humans, these fibers cannot be absorbed by the small intestine and can only be fermented in the large intestine. Dietary fibers are classified as soluble and insoluble fibers based on their solubilities. Insoluble dietary fibers (IDF) are mainly composed of cellulose, lignin, and insoluble hemicellulose, whereas soluble dietary fibers (SDF) are composed of soluble hemicellulose, pectin, gum, and oligosaccharides (Dai & Chau, 2017). Dietary fibers promote the growth of beneficial bacteria in the intestine and produce beneficial metabolites and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and intestinal diseases (Koh et al., 2016). Several types of dietary fibers are used as food additives to improve taste, color, texture, even to provide health benefits (Zhang et al., 2018).

Corn bran, a low-value by-product of corn milling, contains cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, phenols, starch, protein, and ash. It is a rich source of IDF (70.6–86.3%) and SDF (0.2–2.6%) (Rose et al., 2010). Corn bran is bad for the sensory and processing of food, generally used as an animal feed or discarded (Yadav et al., 2016). However, when mixed well with the food matrix, SDF can modulate the fluidity, viscosity, elasticity, and emulsification properties of the food (Tem Thi & Vasanthan, 2019). In addition, SDF has better physiological functions, biological activities, and gel-forming ability than IDF (Ma & Mu, 2016). Considering such advantages, exploring processing methods for increasing the SDF content from food by-products is a promising strategy.

Dietary fiber modification could increase SDF content, physical and chemical properties, and functional activity of these fibers. The processing methods include alkaline hydrogen peroxide treatment, microwave extraction, enzymatic hydrolysis, extrusion, and ultrasonic-assisted extraction. Among these methods, the ultrasonic and extrusion treatments have attracted more attention due to their effectiveness and technical practicality. Ultrasonic processing is widely used as a non-thermal processing technology because of its low energy requirement and convenient operation. Ultrasonic can destroy the structure of dietary fiber and enhance water-holding, oil-holding, and thermal stability (Liu et al., 2021). The twin-screw extrusion technology is a low-cost-high-yield process, combining the characteristics of high pressure, shear, and heat. The twin-screw extrusion can change the structure and molecular weight to improve the physicochemical and biochemical properties, and yield of SDF due to destruction of dietary fiber (Qiao et al., 2021). Cellulase and xylanase can hydrolyze the main components in the cell wall, and enzymatic hydrolysis can be carried out under mild conditions and is environmentally friendly (Xiao et al., 2019). The ultrasonic and extrusion treatments can disrupt the cellular structure, potentially increasing the efficiency of enzymatic hydrolysis and increasing the release of soluble dietary fiber. The changes in dietary fiber's composition, microstructure, and physicochemical properties during processing are well-known. However, studies on the influence of a combination of physical methods and dual enzymatic hydrolysis on the physical, chemical, and functional properties of the SDF in corn bran are sparse. Therefore, we hypothesize that physical methods combined with enzymatic hydrolysis can increase the SDF content and improve the properties of SDF from corn bran.

Herein, twin-screw, twin-screw combined enzymatic, ultrasonic, and ultrasonic combined enzymatic extraction were used to extract SDFs from corn bran. Then the composition, structure, physicochemical properties, and functional activity of the extracted SDF were evaluated, aiming to find the ideal modification method for the SDF extraction from corn bran.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Corn bran was obtained from Changchun Dacheng Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. (Changchun, China). Thermostable α-amylase (Product code: A109182, 3400 U/mL), xylanase (Product code: X195724, enzymatic activity > 100,000 U/g) and cellulose (Product code: C109262, from Aspergillus niger, 10,000 U/g) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Company (Shanghai, China). Alkaline protease (A10154, from Bacillus licheniformis, 200 U/mg) was purchased from Yuanye Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Amyloglucosidase (Product code: A800618, 100,000 U/mL) was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The 2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS)-scavenging activity assay kit was purchased from Beijing Soleibao Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)-scavenging activity assay kit and antioxidant capacity assay kit were obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Mannose, glucosamine, galactosamine, lactose, glucose, galactose, fucose, xylose, rhamnose, and arabinose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Sample preparation

Corn bran was washed with distilled water to remove remaining starch and protein. The dried samples were degreased with n-hexane, ground to a fine powder, and triturated before passing through an 80-mesh sieve. The powder was kept in a vacuum bag and stored at 4 °C to reduce the influence of microorganisms and air on the sample (Liu et al., 2021). Then, samples were prepared using ultrasonic, ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic, extrusion, and extrusion-assisted enzymatic extraction.

2.2.1. Ultrasonic treatment

Corn bran was modified according to a method with slight modification (Liu et al., 2021). The response surface methodology (RSM) was used to optimize the extraction of SDF (Figure S1, S2, Table S1, S2). The powder was dispersed in distilled water (1:31, w/v). An ultrasonic cell disruptor (JY98-IIIN, Ningbo Scientz. Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was employed to treat the corn bran at 480 W for 38 min.

2.2.2. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic treatment

The procedure for the ultrasonic-treatment is the same as described in Section 2.2.1. The enzymatic treatment was determined according to a previously described method, with slight modifications (Zhang et al., 2019). The sonicated sample (10 g) was dispersed in distilled water (120 mL). The solution pH was adjusted to 4.8 and the complex enzymes were added (120 U/g xylanase, 240 U/g cellulase). The mixture was incubated for 2.5 h at 55 °C.

2.2.3. Extrusion treatment

Corn bran powder was extruded on a twin-screw extruder (FMHE36-24, Hunan Fumach Foodstuff Engineering & Technology Co., Ltd., China) following a reported method with slight modification (Zhong et al., 2021). The response surface methodology (RSM) was used to optimize the extraction of SDF (Figure S3, S4, Table S3, S4). The temperature of the twin-screw extruder, screw speed, feeding speed, and water addition were 160 °C, 210 rpm, 16 kg/h, and 29%, respectively.

2.2.4. Extrusion-assisted enzymatic treatment

The extrusion treatment was performed as described in Section 2.2.3. The sonicated sample (10 g) was dispersed in distilled water (120 mL). The pH of the suspension was adjusted to 4.8, complex enzymes (120 U/g xylanase, 240 U/g cellulase) were added, and the mixture was incubated for 2.5 h at 55 °C.

2.2.5. SDF extraction

SDF was extracted using the enzymatic extraction method described by Chen, with slight modifications (Chen et al., 2021). The sample was dispersed in distilled water (1:30 g/mL). After adjusting the pH to 5.5, the suspension was added to α- amylase (100 U/g) and stirred at 95 °C for 1 h. The pH of the suspension was adjusted to 8.5, protease (100 U/g) was added, and the suspension was incubated at 55 °C for 2 h. The pH of the mixture was adjusted to 4.2, and the suspension was incubated at 60 °C for 1 h with amyloglucosidase (200 U/g). Next, the pH of the suspension was adjusted to 4.2, and amyloglucosidase (200 U/g) was incubated at 60 °C for 1 h. The suspension was immediately heated at 100 °C for 15 min to inactivate the enzyme. After enzyme deactivation, the suspension was centrifuged at 4500 × g for 15 min to obtain the supernatant solution. The supernatant was concentrated and added to four volumes of 95% ethanol and stored at 4 °C for 8 h to collect the residue. The residue was then dried by centrifugation.

2.3. Physicochemical properties

The water holding capacity (WHC) and oil holding capacity (ORC) were determined according to a previously described method, with slight modifications (Li et al., 2022). SDF (1 g) was accurately weighed and mixed with deionized water (30 mL) at 25 °C for 18 h. The supernatant was removed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 15 min, and the residue was collected and weighed (W1). The weight of the dried residue was W2, and the following equation was used to calculate WHC.

| (1) |

where W1 is the weight of hydrated SDF, W2 is the weight of dried SDF.

The ORC was determined by the following method. SDF (W3, 1 g) and 20 mL corn oil were mixed in a centrifuge tube at 25 °C for 18 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min to remove the supernatant (free oil). The residue was collected and weighed (W4), and the ORC was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where W4 is the weight of the oily residue and W3 is the weight of the dried sample.

2.4. Structural properties

2.4.1. Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The microstructures of SDF and IDF were determined using the method described by Zhang (Zhang et al., 2019). The samples were placed on a sample stage and sprayed with gold for 60 s. A scanning electron microscope (Phenom-World BV, Eindhoven, Netherlands) was used to observe the surface morphology of the samples at a working voltage of 10 kV. All images were recorded at 1000 × magnification.

2.4.2. Determination of molecular weight

The molecular weight of the samples was determined using a reported method with slight modifications (Gan et al., 2020). Solutions of the samples (10 mg/mL) were prepared with 0.7% Na2SO4 as the mobile phase. The solution was then filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Shimadzu, Japan) with an SRT SEC-100 column (7.8 × 300 mm, 5 μm, Sepax, USA) and RID-20A at 35 °C was used for the analysis, at a flow rate of 2.5 mL/min. A series of dextran standards were used to obtain a standard curve and calculate the molecular mass.

2.4.3. Determination of monosaccharide composition

The hydrolysis of dietary fiber was performed according to a reported method with slight modifications (Yuan et al., 2019). HPLC was used to measure the composition of monosaccharides after pre-column derivatization. 20 mg samples were subjected to acid-hydrolysis with 2 mol/L trifluoroacetic acid at 110 °C for 8 h. The solution was added to 6 mL of 0.5 mol/L methanolic PMP (1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone) solution and 5 mL of 0.3 mol/L sodium hydroxide solution and derivatized in a water bath at 70 °C for 1 h. After cooling, the sample was neutralized with 5 mL of 0.3 mol/L hydrochloric acid and extracted thrice with an equal volume of chloroform. The aqueous layer was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane for HPLC analysis. HPLC measurement conditions were as follows: Diamonsil C18 analytical column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) was used, mobile phase A: phosphate buffer (pH 6.8): acetonitrile (85:15, V/V), mobile phase B: PBS (pH 6.8): acetonitrile (60:40, v/v), flow rate of 0.9 mL/min, column temperature: 40 °C, detection wavelength: 250 nm, and injection volume: 10 μL.

2.4.4. Thermal analysis (Differential scanning Calorimetry)

The thermal properties of the samples were measured by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Q2000, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). The sample (5 mg) was heated from 25 to 300 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

2.4.5. Fourier infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

FT-IR analysis was performed according to a previously described method with slight modification (Liu et al., 2021). The SDF samples were ground and compressed into tablets under 15 MPa pressure for 1 min. All samples were analyzed using an FT-IR spectrophotometer (Spectrum 100, PerkinElmer Co, USA), and the spectral measurement ranged from 400 to 4000 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 with 64 scans. The spectra were analyzed using the OMINIC software (Thermo Fisher Scientific Technology Co., Ltd., USA).

2.4.6. Assessment of crystalline structure

The crystalline structure was determined using the method described by Li with slight modification (Liu et al., 2021). X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used (D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany) to obtain XRD patterns of the samples at operating voltages and currents of 40 kV and 40 mA, respectively. The diffraction intensity was scanned from 5 to 60°, and the angular step width was 0.02°.

2.5. Functional characteristics

2.5.1. Antioxidant activity

Because a single method cannot represent the antioxidant activity in a complex system, we selected ABTS + and DPPH scavenging and ferric-reducing antioxidant activity (FRAP) to measure the antioxidant activity of SDF. Antioxidant activities were determined according to the method described by Qiao with slight modifications (Qiao et al., 2021).

The determination method for DPPH was based on the DPPH kit operation (Jiancheng, Nanjing). Dietary fiber solutions (400 μL) of different concentrations (1.5, 2, 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5 mg/mL) and 600 μL of DPPH mixed working solution were uniformly mixed, and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C in the dark. After centrifugation at 4000 × g for 5 min, the absorbance of the obtained supernatant was measured using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany) at 517 nm. 80% methanol was used as the blank control group. The DPPH clearance rate was calculated using the following formula:

| (3) |

The ABTS + determination method was based on the operation of the ABTS + (Suolaibao, Beijing). SDF solutions (10 μL) of different concentrations (3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 mg/mL) and 190 μL of ABTS + working solution were mixed uniformly, and incubated for 6 min at room temperature in the dark. A microplate reader was used to detect the absorbance of the samples at 405 nm. Ten microliters of deionized water was used as the blank control. The ABTS + scavenging rate was calculated using the following formula:

| (4) |

FRAP was measured according to the instructions of the FRAP kit operation (Jiancheng, Nanjing); 5 μL of SDF solution with different concentrations (3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 mg/mL) and FRAP working solution were uniformly mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. A microplate reader was used to detect the absorbance at 593 nm for each sample. Different concentrations (0.15, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mM) of FeSO4 7H2O were used to generate the standard curve. The FRAP was calculated according to the following standard curve formula:

| (5) |

where y is the concentration (μmol/g) and × is the optical density value (OD value). An R2 value of 0.9993 was obtained.

2.5.2. Nitrite adsorption capacity

The scavenging activity of nitrogen dioxide radicals was determined using the method described by Luo with slight modifications (Luo et al., 2018). To simulate the environment of the small intestine and stomach, the sample (0.1 g) was mixed with 5 mL of NaNO2 (20 μg/mL), and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 and 2.0, respectively. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After centrifugation at 4800 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant (0.4 mL) was transferred to a glass tube. The solution was added to p-aminobenzene sulfonic acid and N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride to measure the concentration of NaNO2 using a spectrophotometer at 538 nm. The Nitrite adsorption capacity (NIAC) was calculated as follows:

| (6) |

where m1 and m2 are the contents of NaNO2 in the solution before and after adsorption, respectively, and w is the SDF weight.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All analyses were determined in triplicate and analyzed using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Moreover, the figures were depicted by Origin 2018 software (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemical composition

As shown in Table 1, the extraction yield of SDF was significantly increased by the modification method (p > 0.05). The extrusion assist-enzyme SDF (EESDF) had the highest yield (10.53%), followed by ultrasonic assist-enzyme SDF (UESDF) (6.98%), extrusion SDF (ESDF) (6.54%), ultrasonic SDF (USDF) (4.58%), and SDF (2.42%). The results suggest that twin-screw extrusion combined with enzymatic hydrolysis effectively improves the SDF extraction rate. Moreover, the yield of EESDF was higher than sweet potato residue (3.29 g/100 g) (Liu et al., 2021), polygonatum odoratum (9.8 g/100 g) (Lan et al., 2012), and modified carrot (2.06 g/100 g)(Dong et al., 2022). The ultrasonic approach is a non-thermal processing method, wherein the ultrasonic waves cause the cavitation nucleus to vibrate, grow, and accumulate energy, which results in negative pressure in the liquid. In addition, acoustic cavitation energy can degrade long-chain polysaccharides into short-chain polysaccharides, increasing the reducing sugar content (Yan et al., 2019). However, the mechanism of twin-screw extrusion involves the production of high temperature, shear force, and pressure to destroy the samples, which increases the extraction rate of SDF. The results proved that these two treatments could destroy the structure of the cell wall and lead to the dissolution of SDF. In addition, the results show that the twin-screw extrusion treatment is more conducive to enzymatic hydrolysis than ultrasonic treatment. These results suggest that the twin-screw method might lead to a looser spatial structure of the dietary fiber, allowing more binding sites for enzyme treatment, and rendering enzymatic hydrolysis more effective (Qiao et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Chemical composition, yield (%), and average molecular weight of SDFs.

| Sample | SDF | USDF | UESDF | ESDF | EESDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction yield % | 2.42 ± 0.14e | 4.58 ± 0.08d | 6.98 ± 0.15b | 6.54 ± 0.13c | 10.53 ± 0.24a |

| WHC(g/g) | 0.81 ± 0.02e | 1.40 ± 0.13d | 2.89 ± 0.14b | 2.06 ± 0.07c | 3.22 ± 0.23a |

| OHC(g/g) | 1.57 ± 0.06d | 2.27 ± 0.12c | 2.87 ± 0.06a | 2.28 ± 0.08c | 2.55 ± 0.07b |

| Average molecular weight (Da) | 1.58 × 104b | 3.07 × 104a | 6.41 × 103d | 1.22 × 104c | 4.00 × 103e |

Results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (n = 3); a, b, c, d, e Values in the same row are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

3.2. Physicochemical characteristics

The WHC and OHC of the SDFs, which were prepared using different treatments, were shown in Table 1. Compared to untreated SDF, the WHC of USDF, UESDF, ESDF. The was significantly enhanced (p < 0.05). These results indicated that the four treatment methods changed the dietary fiber structure and increased the surface area. The microstructure of SDF became loose, and the exposure of hydrophilic groups increased, causing an increase in the water-holding capacity. The higher WHC (3.22 g/g) of EESDF could be attributed to the smaller molecular weight and larger surface area.

ORC is a vital indicator for the retention of fat and fat-soluble flavors during food processing; therefore, SDF is also used as a fat substitute (Niu et al., 2020). Compared with untreated SDF, USDF, and ESDF were not significantly different (p > 0.05). After cellulase and hemicellulase treatments, the ORC of SDF increased from 1.57 to 2.87 and 2.55 g/g, respectively. The ORC is closely related to the microscopic morphology, charge density, and surface hydrophobic groups of the dietary fiber (Ma & Mu, 2016). The ultrasonic, twin-extrusion and enzyme treatments manipulated the charge density of the SDF and caused the exposure of hydrophobic groups, leading to an increase in ORC. These results are consistent with previous studies (Luo et al., 2017, Qiao et al., 2021).

3.3. Structural properties

3.3.1. Microstructure

The surface microstructures of SDF (A-E) and IDF (a-e) extracted using different methods are shown in Figure S5. It was apparent that SDF was released during treatment through microstructural changes in IDF. Untreated IDF exhibited a dense network structure. The IDF was damaged by the ultrasonic cavitation effect, forming many cavities on the surface. However, the twin-screw extrusion treatment destroyed the dense, layered structure, leading to the creation of a loose structure, and exposing the internal structure. Cellulase and xylanase treatments further destroyed the structure of the dietary fiber, forming a more open structure. Compared with the ultrasonic-treated samples, the IDF treated by twin-screw extrusion showed a wider specific surface area. All these illustrate the difference in the extraction effect of the different treatment methods combined with enzymatic hydrolysis in 3.1. The structure of the enzymatically-treated wheat bran was analyzed, and it was found that cell walls were partially degraded, while cellulose and hemicellulose were the main components of the cell wall (Zhang et al., 2019). These images reveal the mechanism of the increase in SDF. Compared with untreated SDF, SDF extracted with ultrasonic and extrusion treatments had a porous structure with a larger specific surface area. Enzymatic hydrolysis further decreased the particle size and unfixed the structure of the SDF. These results indicated that the ultrasonic and extrusion treatments destroyed the cross-links between SDF molecules, and the enzyme treatments aggravated this damage and led to loose porous structures. These structural changes may alter the adsorption capacity, oxidation resistance and ability of SDF to bind water.

3.3.2. Monosaccharide composition

Table 2 summarizes the monosaccharide composition of SDFs extracted using different methods. Modified or unmodified soluble dietary fiber was composed of six monosaccharides: mannose, rhamnose, galacturonic acid, glucose, xylose, and arabinose. In all samples, only rhamnose and a higher proportion of galacturonic acid were observed in SDF, which were the main components of pectin. Pectin is present in plant cell walls and interlayers. Ultrasonic treatment and twin-screw extrusion treatment destroy the structure of pectin, resulting in the breaking of glycosidic bonds to produce monosaccharides. Similar results were reported in the black soybean hull and coconut flour (Du et al., 2021, Feng, Dou, Alaxi, Niu, & Yu, 2017). As well-known, mannose, rhamnose, galacturonic acid, xylose, and arabinose are the main components of hemicellulose, and glucose is the primary component of cellulose. Moreover, ultrasonic and twin-screw treatment significantly increased the ratio of xylose and arabinose, indicating that the connection between cellulose and hemicellulose was destroyed. Treatment with the compound enzyme resulted in a significant increase in the proportion of glucose content, which proved that the cellulase and xylanase treatments significantly promoted the hydrolysis of cellulose. These results are consistent with previous research (Liu et al., 2021).

Table 2.

Monosaccharide composition of SDF (%).

| Monosaccharides (%) | SDF | USDF | UESDF | ESDF | EESDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mannose | 2.41 ± 0.01c | 2.57 ± 0.01b | 0.00 | 1.56 ± 0.01d | 3.69 ± 0.01a |

| Rhamnose | 1.39 ± 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Galacturonic acid | 15.04 ± 0.02a | 7.79 ± 0.01b | 3.36 ± 0.02e | 6.36 ± 0.01c | 5.83 ± 0.03d |

| Glucose | 13.79 ± 0.01d | 3.33 ± 0.01e | 57.53 ± 0.01a | 16.70 ± 0.01c | 24.45 ± 0.01b |

| Xylose | 35.77 ± 0.02c | 37.98 ± 0.01a | 19.08 ± 0.01e | 36.32 ± 0.02b | 30.85 ± 0.03d |

| Arabinose | 31.59 ± 0.02a | 48.32 ± 0.01a | 20.01 ± 0.01e | 39.06 ± 0.04b | 35.17 ± 0.04c |

a,b,c,d,eValues followed by different letters in the same line are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Ultrasonic treatment and twin-screw extrusion treatment could destroy the lignin-carbohydrate complex (lignin-carbohydrate complex), which results in the destruction of the bond between hemicellulose and cellulose or lignin (Ji et al., 2020). Compared with cellulose, hemicellulose has more branches and a relatively lower degree of polymerization, which is easier to degrade and dissolve. The enzymatic treatment further degraded cellulose and hemicellulose, changed the dietary fiber structure and the monosaccharide composition.

3.3.3. Molecular weight distribution

Significant differences were observed in the molecular weights of SDF obtained by different extraction methods, and the results are shown in Figure S6. The molecular weight ranged from 0.16 to 58 kDa, and the spectra comprised 3–5 peaks. In addition, the retention times of all samples were 11.5, 17.8, 18.8, 19.2, and 19.9 min, respectively. Compared with untreated SDF, the ration of average to high molecular weight of UESDF, ESDF, and EESDF samples decreased, and the percentage of low molecular weight SDF increased. These results were attributed to the high temperature, pressure of extrusion, and the complex enzyme treatment that destroyed the molecular chain of SDF, resulting in the increase of the short-chain SDF small molecules. It is worth noting that USDF (30.73 kDa) had the highest average molecular weight, which may be due to the cavitation effect of ultrasound. The cavitation effect ruptures the cell wall, breaks the cellulose and hemicellulose chains, and increases the solubility of SDF, leading to an increase in the dissolution ratio of macromolecule SDF. Similar results were obtained by ultrasonic treatment of potato cell walls and grapefruit peels (Gan et al., 2020, Khodaei and Karboune, 2013).

3.3.4. Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy was used to characterize the chemical functional groups and structural changes of substances. The spectra of SDFs obtained from different treatments are shown in Fig. 1. The spectral band at 3400 cm−1 represents the O—H stretching vibration peak. Ultrasonic, extrusion, and enzyme treatment caused the spectrum to redshift at 3400 cm−1, and the peak intensity decreased. These results indicate that ultrasonic and extrusion treatments could promote the decomposition of cellulose and hemicellulose, and the cellulase and xylanase further destroyed the hydrogen bonds between cellulose and hemicellulose molecules. This process might increase the exposure of the functional groups, leading to changes in their physical and chemical properties (Huang, Ding, Zhao, Li, & Ma, 2018, Qiao et al., 2021). The characteristic absorption peak of the polysaccharides at 2930 cm−1 represents the C—H vibration of the methyl or methylene chemical groups. The peaks at 1643 and 1735 cm−1 were the characteristic absorptions of C O or COO– (carboxyl functional group) of uronic acid. Notably, twin-screw extrusion combined with enzyme treatment had the most substantial absorption at 1643 cm−1. These results were attributed to the structure of dietary fiber being severely destroyed by extrusion and enzymatic hydrolysis, which increased the uronic acid content. The peak at 1410 cm−1 is attributed to the C—H vibration, representing the aromatic lignin group (Dong et al., 2020). The 1300–950 cm−1 range is the “fingerprint region” of polysaccharides related to the C—O—C and C—O—H stretching vibrations in glucopyranose (Lettow et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

FT-IR spectra of the SDF, USDF, UESDF, ESDF, and EESDF.

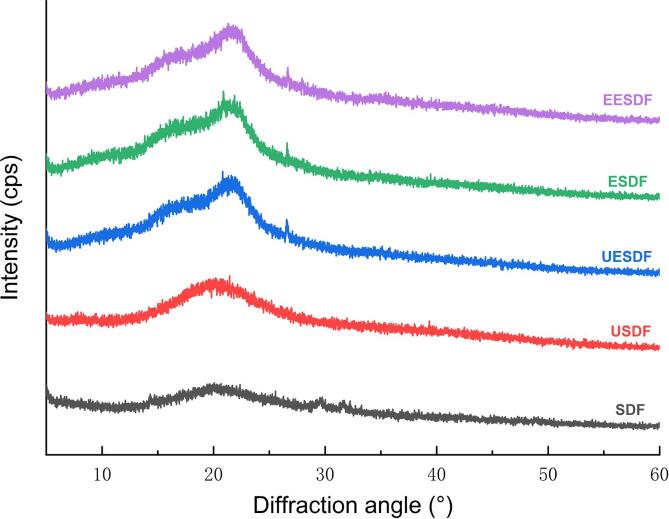

3.3.5. Crystalline structure

XRD was used to analyze the influence of different processing methods on the crystal structure of the SDF. The XRD diffractograms of the products from the various processing methods are shown in Fig. 2. The results showed that the SDF was similar at 2θ values at approximately 22°, and the treatments did not change the crystal structure. In addition, SDF has a diffraction peak at approximately 26°, indicating that SDF coexists in a crystalline and amorphous state (Zhang et al., 2017). The crystallinity of SDF decreased significantly after treatment. This result showed that ultrasonic and extrusion treatments could destroy the crystal structures of SDFs, change the crystal structure from order to disorder, and increase the non-crystalline component. A similar result was found in the treatment of pectin using ultrasound (Wang et al., 2016).

Fig. 2.

Soluble dietary fiber from corn bran using different extraction of X-ray diffraction analysis.

3.3.6. Thermal characteristics

DSC was used to analyze the thermal transformation of dietary fiber. The results of the DSC analysis of SDFs are shown in Fig. 3. The samples showed a prominent endothermic peak at 100–150 °C, attributed to the volatilization of water, hydrogen bonding, and conformational transition of the polysaccharides (Wang et al., 2016). After the treatment, the endothermic peak shifted to the right, and the shifts for the twin-screw extrusion combined with enzyme treatment were more pronounced. This phenomenon was attributed to twin-screw extrusion, which might severely destroy the intramolecular hydrogen bonds, resulting in a stable structure, reduced bound-water, and increased endothermic temperature. All samples had prominent exothermic peaks between 230 and 300 °C, representing the thermal decomposition of sugars and elimination of volatile products. The most vigorous heat flow intensity was observed in the untreated SDF, indicating that the untreated SDF had poor thermal stability. Ultrasonic treatment, extrusion treatment, and enzyme treatment improved the thermal stability. Consistent with our results, previous studies have shown that twin-screw extrusion treatment (Qiao et al., 2021, Qiao et al., 2021), ultrasonic treatment (Tsalagkas et al., 2016), and enzyme treatment (Zhang et al., 2019) improved the stability of SDF. Therefore, the modified SDF has better stability for thermally-processed foods and is more suitable for functional food additives.

Fig. 3.

The curves of DSC of SDF, USDF, UESDF, ESDF, and EESDF.

3.4. Functional properties

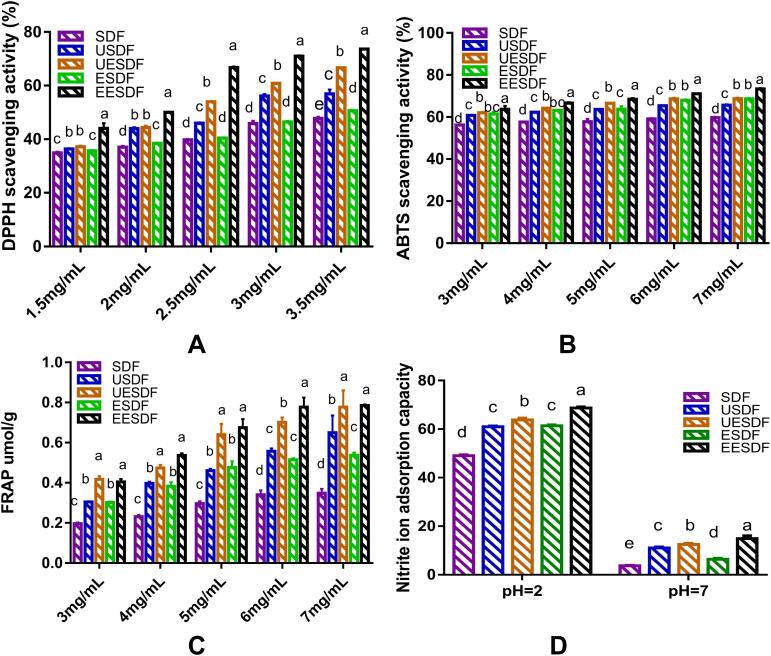

3.4.1. Antioxidant activity

The DPPH scavenging activities of SDFs subjected to different treatments are shown in Fig. 4A. DPPH is mainly used to measure the hydrogen supply capacity of SDF as a hydrogen donor, and has maximum absorption at 517 nm. It could be seen that within the test concentration range (1.5–3.5 mg/mL), all samples had DPPH scavenging activity. At 1.5–3 mg/mL concentrations, no significant differences were observed between SDF and ESDF. EESDF showed the highest DPPH scavenging activity at all concentrations. These results indicated that the complex enzyme treatment could improve the antioxidant activity of SDF, which might be due to the release of bound polyphenols. The lower molecular weight and larger specific surface area caused by the enzyme treatment might help increase the antioxidant activity (Zhong et al., 2021, Du et al., 2021).

Fig. 4.

The DPPH scavenging activity (A), ABTS scavenging activity (B), FRAP (C), and Nitrite ion adsorption capacity (D) of SDF, USDF, UESDF, ESDF, and EESDF.

The ABTS scavenging activities of different SDFs are shown in Fig. 4B. At all tested concentrations (3–7 mg/mL), the scavenging activities of USDF, UESDF, ESDF, and EESDF were higher than the scavenging activities of untreated SDF. The antioxidant activities of UESDF and ESDF were similar, and EESDF had the highest ABTS removal activity.

FRAP represents the reducing power of antioxidants. At low pH, the samples could reduce Fe3+-TPTZ (2,4,6-tripyridin-2-yl-1,3,5-triazine) to produce the blue-violet Fe2+-TPTZ. The total antioxidant capacity was determined at 593 nm. As shown in Fig. 4C, ultrasonic, twin-screw, and enzymatic hydrolysis treatments improved the ion-reduction activity. As the concentration increased, the FRAP of USDF, UESDF, ESDF, and EESDF exhibited an upward trend. Except for at the highest concentration, UESDF and EESDF had similar antioxidant activities to FRAP. These results showed that the dual-enzyme treatment significantly increased the antioxidant activity, consistent with the scavenging activities of DPPH and ABTS. The functional activity of dietary fiber is related to factors such as structure, composition, and conjugates. Compared with high molecular weight dietary fibers, low molecular weight SDFs have more accessible free radicals and reducing groups (hydroxyl and amino groups). High molecular weight SDFs are challenging to function in the reaction process due to their compact structure. In addition to the relative molecular weight, the composition and connection mode of monosaccharides are also directly related to the functional properties of SDF. The higher content of rhamnose and the connection mode of arabinose and mannose will affect the antioxidant activity of SDF. The difference in antioxidant activity of different modification methods may be attributed to monosaccharide composition and molecular weight. In addition, it has been reported that fungal oxidative and hydrolyzing enzymes can generate new soluble dietary fibers that demonstrate up to 20 times higher antioxidant activity (Margetić et al., 2021). Our findings are consistent with previous reports and indicate that enzymatic treatment could improve the antioxidant activity of SDF.

3.4.2. Nitrite adsorption capacity

Nitrite interacts with tertiary and secondary amines in the stomach to generate nitrosamines and is harmful to health. The adsorption ability of SDF in pH 2 (49.0–68.7 mg/g) environment was significantly higher than that at the absorption ability at pH 7 (3.69–14.9 mg/g). These results indicated that SDFs eliminated nitrite ions, mainly in the stomach. The SDF obtained by the four treatment methods had higher adsorption capacity for nitrite ions than the untreated SDF, and EESDF had a highest nitrite-ion adsorption capacity (Fig. 4D). According to the previous studies, the low pH conditions benefited from the adsorption of nitrite ions, which was attributed to the combined effect of dietary fibers and phenolic acids such as p-coumaric acid or ferulic acid. In addition, a higher number of carboxyl and hydroxyl groups are exposed on the surface of the dietary fiber, which generates more hollow structures and larger specific surface areas, which results in a more robust adsorption capacity (Zheng et al., 2018, He et al., 2019). In summary, the four treatment methods increased the adsorption capacity for nitrite ions, which indicates their potential as functional ingredients in the food industry.

4. Conclusion

This study evaluated four methods for SDF extraction from corn bran to assess the composition, physicochemical, structural, and functional properties. In general, ultrasonic treatment, twin-screw treatment, and enzyme treatment significantly increased the SDF extraction rate. These methods improved the physical and chemical properties and the functional activity, which were attributed to different microstructures and molecular weights. It is worth noting that EESDF exhibits the lowest molecular weight, highest extraction rate, highest water holding capacity, highest nitrite ion adsorption capacity, and superior antioxidant activity. Physical modification combined with enzymatic treatment is an effective method for the preparation of modified SDF.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sheng Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Nannan Hu: Formal analysis, Investigation. Jinying Zhu: Formal analysis. Mingzhu Zheng: Investigation, Supervision. Huimin Liu: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Jingsheng Liu: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0400700, 2016YFD0400702) and Scientific and technological innovation team project for outstanding young and middle-aged of Jilin Province (20210509026RQ).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100298.

Contributor Information

Huimin Liu, Email: liuhuimin@jlau.edu.cn.

Jingsheng Liu, Email: liujingsheng@jlau.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Chen H., Xiong M., Bai T., Chen D., Zhang Q., Lin D., Qin W. Comparative study on the structure, physicochemical, and functional properties of dietary fiber extracts from quinoa and wheat. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2021;149:111816. [Google Scholar]

- Dai F.J., Chau C.F. Classification and regulatory perspectives of dietary fiber. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2017;25:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong R., Liao W., Xie J., Chen Y., Peng G., Xie J.…Yu Q. Enrichment of yogurt with carrot soluble dietary fiber prepared by three physical modified treatments: Microstructure, rheology and storage stability. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 2022;75 [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Wang D., Hu R., Long Y., Lv L. Chemical composition, structural and functional properties of soluble dietary fiber obtained from coffee peel using different extraction methods. Food Research International. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Wang L., Huang X., Jing H., Ye X., Gao W.…Wang H. Effects of different extraction methods on structure and properties of soluble dietary fiber from defatted coconut flour. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2021;143:111031. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Dou W., Alaxi S., Niu Y., Yu L. Modified soluble dietary fiber from black bean coats with its rheological and bile acid binding properties. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;62:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gan J., Huang Z., Yu Q., Peng G., Chen Y., Xie J., Xie M. Microwave assisted extraction with three modifications on structural and functional properties of soluble dietary fibers from grapefruit peel. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;101 doi: 10.1039/d0fo00760a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Guo J., Zhou Q., Fang F. Adsorption characteristics of nitrite on natural filter medium: Kinetic, equilibrium, and site energy distribution studies. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2019;169:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Ding X., Zhao Y., Li Y., Ma H. Modification of insoluble dietary fiber from garlic straw with ultrasonic treatment. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 2018;42 Article e13399. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q.H., Yu X.J., Yagoub A.G.A., Chen L., Zhou C.S. Efficient removal of lignin from vegetable wastes by ultrasonic and microwave-assisted treatment with ternary deep eutectic solvent. Industrial Crops and Products. 2020;149 [Google Scholar]

- Khodaei N., Karboune S. Extraction and structural characterisation of rhamnogalacturonan I-type pectic polysaccharides from potato cell wall. Food Chemistry. 2013;139:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh F.D., Vadder P., Kovatcheva-Datchary F. Backhed from dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan G.S., Chen H.X., Chen S.H., Tian J.G. Chemical composition and physicochemical properties of dietary fiber from Polygonatum odoratum as affected by different processing methods. Food Research International. 2012;49:406–410. [Google Scholar]

- Lettow M., Grabarics M., Mucha E., Thomas D.A., Polewski L., Freyse J., Pagel K. IR action spectroscopy of glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2020;412:533–537. doi: 10.1007/s00216-019-02327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Niu L., Guo Q., Shi L., Deng X., Liu X., Xiao C. Effects of fermentation with lactic bacteria on the structural characteristics and physicochemical and functional properties of soluble dietary fiber from prosomillet bran. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2022;154:112609. [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Zhou S., Li Y., Tian J., Zhang C. Structure, physicochemical properties and effects on nutrients digestion of modified soluble dietary fiber extracted from sweet potato residue. Food Research International. 2021;150 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yi S., Ye T., Leng Y., Hossen M.A., Sameen D.E., Qin W. Effects of ultrasonic treatment and homogenization on physicochemical properties of okara dietary fibers for 3D printing cookies. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2021;77 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhang H., Yi C., Quan K., Lin B. Chemical composition, structure, physicochemical and functional properties of rice bran dietary fiber modified by cellulase treatment. Food Chemistry. 2021;342 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Wang Q., Fang D., Zhuang W., Chen C., Jiang W., Zheng Y. Modification of insoluble dietary fibers from bamboo shoot shell: Structural characterization and functional properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;120:1461–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Wang Q., Zheng B., Lin L., Chen B., Zheng Y., Xiao J. Hydration properties and binding capacities of dietary fibers from bamboo shoot shell and its hypolipidemic effects in mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2017;109:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M.M., Mu T.H. Effects of extraction methods and particle size distribution on the structural, physicochemical, and functional properties of dietary fiber from deoiled cumin. Food Chemistry. 2016;194:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Mu T. Modification of deoiled cumin dietary fiber with laccase and cellulase under high hydrostatic pressure. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2016;136:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margetić A., Stojanović S., Ristović M., Vujčić Z., Dojnov B. Fungal oxidative and hydrolyzing enzymes as designers in the biological production of dietary fibers from triticale. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2021;145 [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y., Fang H., Huo T., Sun X., Gong Q., Yu L. A novel fat replacer composed by gelatin and soluble dietary fibers from black bean coats with its application in meatballs. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2020;122:109000. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao C.C., Zeng F.K., Wu N.N., Tan B. Functional, physicochemical and structural properties of soluble dietary fiber from rice bran with extrusion cooking treatment. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;121 [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H., Shao H., Zheng X., Liu J., Liu J., Huang J.…Guan W. Modification of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) residues soluble dietary fiber following twin-screw extrusion. Food Chemistry. 2021;335 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D.J., Inglett G.E., Liu S.X. Utilisation of corn (Zea mays) bran and corn fiber in the production of food components. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2010;90:915–924. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tem Thi D., Vasanthan T. Modification of rice bran dietary fiber concentrates using enzyme and extrusion cooking. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;89:773–782. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalagkas D., Lagana R., Poljansek I., Oven P., Csoka L. Fabrication of bacterial cellulose thin films self-assembled from sonochemically prepared nanofibrils and its characterization. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2016;28:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Ma X., Jiang P., Hu L., Zhi Z., Chen J., Liu D. Characterization of pectin from grapefruit peel: A comparison of ultrasound-assisted and conventional heating extractions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;61:730–739. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Weng H.F., Ni H., Hong Q.L., Lin K.H., Xiao A.F. Physicochemical and gel properties of agar extracted by enzyme and enzyme-assisted methods. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;87:530–540. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M.P., Hicks K.B., Johnston D.B., Hotchkiss A.T., Jr., Chau H.K., Hanah K. Production of bio-based fiber gums from the waste streams resulting from the commercial processing of corn bran and oat hulls. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;53:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.K., Wu L.X., Cai W.D., Xiao G.S., Duan Y.Q., Zhang H.H. Subcritical water extraction-based methods affect the physicochemical and functional properties of soluble dietary fibers from wheat bran. Food Chemistry. 2019;298 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.124987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q., Lin S., Fu Y., Nie X.R., Liu W., Su Y., Wu D.T. Effects of extraction methods on the physicochemical characteristics and biological activities of polysaccharides from okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2019;127:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Wang H., Cao X., Wang J. Preparation and modification of high dietary fiber flour: A review. Food Research International. 2018;113:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.Y., Liao A.M., Thakur K., Huang J.H., Zhang J.G., Wei Z.J. Modification of wheat bran insoluble dietary fiber with carboxymethylation, complex enzymatic hydrolysis and ultrafine comminution. Food Chemistry. 2019;297 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.124983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zeng G., Pan Y., Chen W., Huang W., Chen H., Li Y. Properties of soluble dietary fiber-polysaccharide from papaya peel obtained through alkaline or ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2017;172:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Li Y., Xu J., Gao G., Niu F. Adsorption activity of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) cake dietary fibers: Effect of acidic treatment, cellulase hydrolysis, particle size and pH. RSC Advances. 2018;8:2844–2850. doi: 10.1039/c7ra13332d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L., Fang Z., Wahlqvist M.L., Hodgson J.M., Johnson S.K. Multi-response surface optimisation of extrusion cooking to increase soluble dietary fibre and polyphenols in lupin seed coat. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2021;140:110767. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.