Abstract

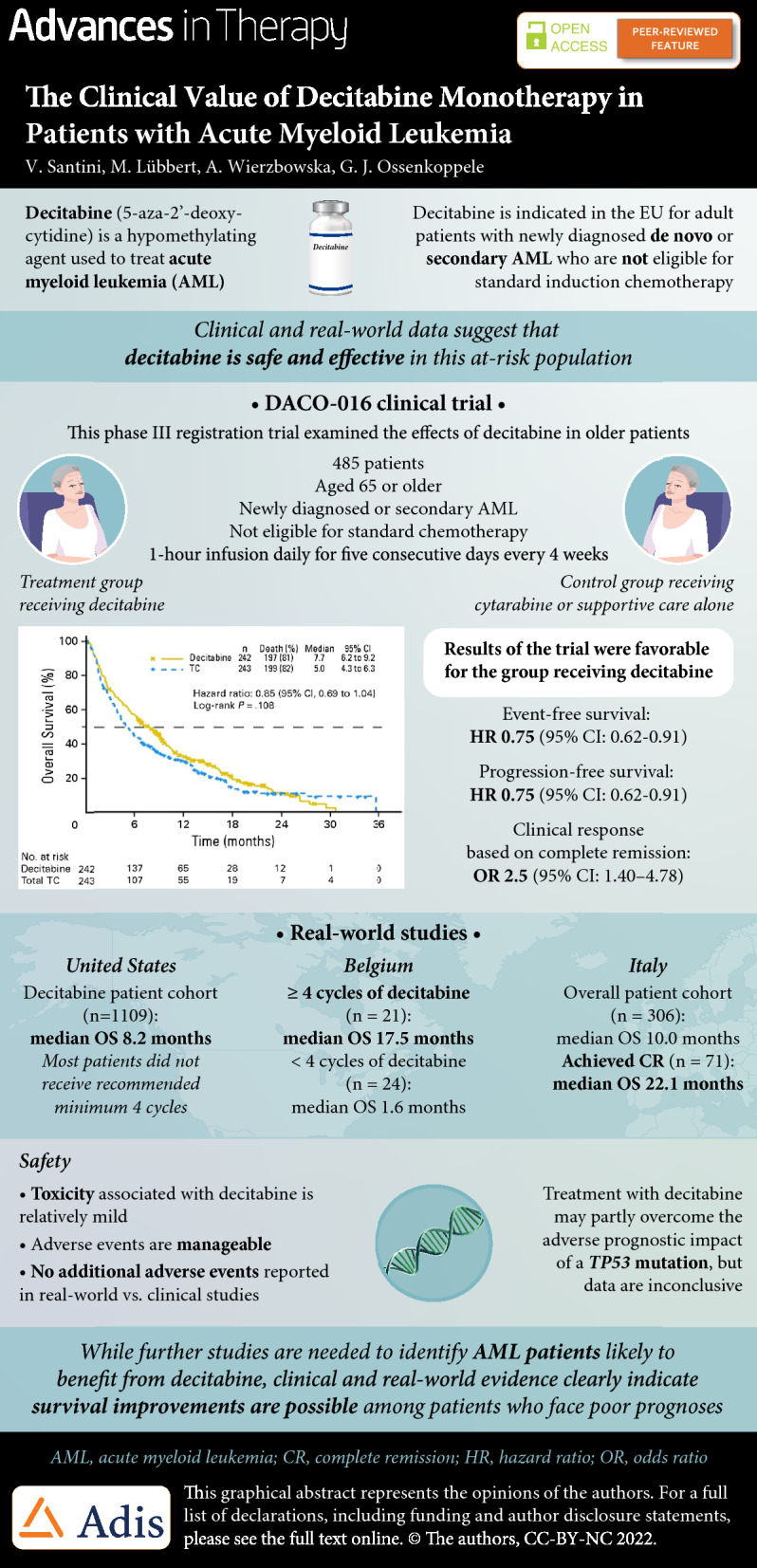

Decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) is a hypomethylating agent used in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Decitabine inhibits DNA methyltransferases, causing DNA hypomethylation, and leading amongst others to re-expression of silenced tumor suppressor genes. Decitabine is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed de novo or secondary AML who are not eligible for standard induction chemotherapy. The initial authorization in 2012 was based on the results of the open-label, randomized, multicenter phase 3 DACO-016 trial, and supported by data from the supportive phase 2 open-label DACO-017 trial. Compared with standard care, decitabine significantly improved overall survival, event-free survival, progression-free survival, and response rate. Decitabine was generally well tolerated, offering a valuable treatment option in patients with AML irrespective of age, especially for patients achieving a complete response. Several observational “real-life” studies confirmed these results. In contrast to standard chemotherapy, the presence of adverse-risk karyotypes or TP53 mutations does not negatively impact sensitivity to hypomethylating therapy albeit with lower durability. Data suggest a potential positive effect of decitabine in patients with monosomal karyotype-positive AML. For the time being, decitabine is an appropriate option as monotherapy for patients with AML who are unfit to receive more intensive combination therapies, but emerging data suggest that decitabine-based doublet or triplet combinations may be future treatment options for patients with AML.

Infographic

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-021-01948-8.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, Decitabine, Elderly, Hypomethylating agents, HMAs

Video Abstract (MP4 22805 kb)

Key Summary Points

| Decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) is a hypomethylating agent (HMA) used in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) |

| Decitabine is indicated in the EU for the treatment of adult patients with newly diagnosed de novo or secondary AML who are not eligible for standard induction chemotherapy |

| In the registration trial, decitabine significantly improved overall survival, event-free survival, progression-free survival, and response rate compared with standard care, and was generally well tolerated |

| Similar results were seen in real-world studies |

| In contrast to standard chemotherapy, the presence of adverse-risk karyotypes or TP53 mutations does not negatively impact sensitivity to hypomethylating therapy |

| Future areas of research are necessary to identify biomarkers of response and resistance, and to investigate the use of decitabine-based combination to further improve outcomes in patients with AML |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including an infographic, video abstract, slide deck and script to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23500908.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clonal disorder characterized by an increase in the number of abnormal myeloid precursor cells in the bone marrow. As a result, the production of normal blood cells is compromised. This shortage results in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. AML is the most common form of acute leukemia in adults, and mostly affects patients over 65 years of age [1]. The incidence of AML is similar in Europe and the USA, with rates of 3.7 per 100,000 and 4.0 per 100,000, respectively [2, 3].

In the period 2010–2016, the 5-year survival rate for AML was 47.5% for patients younger than 65 years and 8.2% for patients 65 years of age or older [1]. Prognosis is poor in older patients; median survival in this age group is 2.4 months and varies from 3.9 months in patients aged 65–74 years to 1.4 months in patients aged 85 years or older [4–6].

Cytogenetic abnormalities and molecular abnormalities, as defined in the 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) AML recommendations, are important predictors of remission rate, relapse risk, and survival [7]. The 5-year survival rates for patients with favorable, intermediate, and unfavorable risk cytogenetics are 55–65%, 24–41%, and 5–14%, respectively [8–10]. Survival rates are even lower in older patients: 34%, 13%, and 2%, respectively [11].

Standard treatment for patients with AML is intensive induction chemotherapy, usually with a combination of an anthracycline plus cytarabine (cytosine arabinoside) [10]. Despite improvements in outcomes for younger patients in recent decades, there has been little progress in improving prognosis for patients older than 60 years [7]. In those who are not eligible for standard induction chemotherapy, treatment options are low-dose cytarabine (LDAC), LDAC plus glasdegib, the hypomethylating agents decitabine or azacitidine (HMAs), HMAs combined with venetoclax, or best supportive care [10].

HMAs target the epigenetic processes involved in carcinogenesis. Epigenetic modification is an important regulator of gene transcription, and its role in carcinogenesis has been a topic of considerable interest in the past few years. Of all epigenetic modifications, hypermethylation has been the most extensively studied. Hypermethylation inhibits activation of promoters and therefore transcription of tumor suppressor genes, leading to gene silencing [12].

This review focuses on decitabine (Janssen-Cilag International N.V., B-2340 Beerse, Belgium, http://www.janssen.com/), a HMA which is indicated for the treatment of adults with newly diagnosed de novo or secondary AML, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, who are not eligible for standard induction chemotherapy. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Mechanism of Action and Administration

Decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) is a cytidine deoxynucleo-9 side analogue. It inhibits DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), leading to DNA hypomethylation including gene promoter regions. This in turn may lead to re-expression of silenced tumor suppressor genes and others involved in cellular proliferation and differentiation. In several leukemia cell lines, decitabine elicited morphological and functional differentiation at concentrations that inhibited cellular DNA methylation. Moreover, decitabine also induces cytotoxicity by incorporation into DNA and the generation of DNA–DNMT adducts that interfere with DNA synthesis during cell replication, resulting in apoptosis. In addition, decitabine affects angiogenesis, decreasing vessel formation in different tumor models [13, 14].

Decitabine is administered at a dose of 20 mg/m2 body surface area by intravenous (IV) infusion over 1 h daily for five consecutive days in a treatment cycle. The cycle should be repeated every 4 weeks, depending on the patient’s clinical response and toxicity for a minimum of four cycles; however, more may be needed to achieve a complete or partial remission. Therefore, treatment may be continued as long as the patient continues to derive a benefit, such as a response or stable disease.

Registration Trial DACO-016

In 2012, a marketing authorization valid throughout the European Union was issued for decitabine monotherapy for the treatment of patients aged 65 years and older with newly diagnosed or secondary AML who are not eligible for standard induction chemotherapy. The initial authorization was based on the results of the open-label, randomized, multicenter phase 2 DACO-016 trial, and supported by data from the phase 2 open-label DACO-017 trial in subjects with AML [15, 16]. Patients with newly diagnosed de novo or secondary AML received either decitabine monotherapy or control treatment (the physician’s preferred treatment of choice [TC] of cytarabine or supportive care alone).

The pivotal DACO-016 trial enrolled 485 patients from 65 international sites, of whom 242 received decitabine and 243 received TC.

Eligible patients were 65 years or older, had newly diagnosed histologically confirmed de novo or secondary AML, and had a poor or intermediate cytogenetic risk profile, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2, and adequate organ function determined by laboratory evaluation. Exclusion criteria were a history of acute promyelocytic leukemia or any other active systemic malignancy, previous chemotherapy (except hydroxyurea) for any myeloid disorder, and being a potential candidate for bone marrow or stem cell transplant within 12 weeks after randomization.

Decitabine 20 mg/m2 was administered by 1-h IV infusion once daily for five consecutive days every 4 weeks. Cytarabine 20 mg/m2 was administered subcutaneously once daily for 10 consecutive days, and repeated every 4 weeks. Patients also received supportive care and could continue the treatment as long as they had clinical benefit.

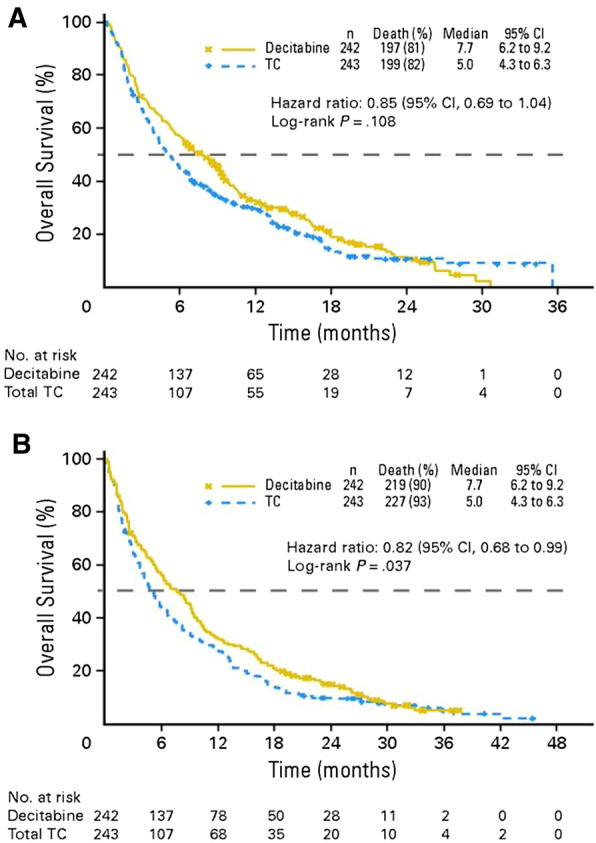

The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival (OS). At the clinical data cutoff in October 2009, 396 patients had died: 197 in the decitabine group and 199 in the TC group. Median OS in the intention-to-treat population was 5.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 4.3–6.3 months) in the TC arm versus 7.7 months (95% CI 6.2–9.2 months) in the decitabine arm (Fig. 1). This equated to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.85 (95% CI 0.69–1.04; p = 0.1079). Analysis of OS data with an additional year of follow-up (October 2010) enforced earlier data: median OS was 5.0 months in the TC arm and 7.7 months in the decitabine arm (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.68–0.99; p = 0.0373).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of overall survival with decitabine versus physician’s treatment choice (TC) in the intention-to-treat population of the DACO-106 study a at the protocol-specified clinical cutoff date in 2009, and b in an ad hoc mature analysis in 2010 [16]

Secondary endpoints were event-free survival (EFS), progression-free survival (PFS), and clinical response based on morphologic complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete platelet recovery (CRp). Median EFS was 3.5 months in the decitabine arm compared with 2.1 months in the TC arm (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.62–0.91; p = 0.0029), and median PFS was 3.7 months in the decitabine arm versus 2.1 months in the TC arm (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.62–0.91; p = 0.0036) [17]. In the decitabine arm, 17.8% of patients achieved CR or CRp compared with 7.8% in the TC arm (odds ratio [OR] 2.5; 95% CI 1.40–4.78; p = 0.0011). All efficacy results and OS are summarized in Table 1 [17].

Table 1.

Summary of the efficacy results in the DACO-016 study (intention-to-treat population) [17]

| TC (n = 243) | Decitabine (n = 242) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival, median (95% CI), months | ||||

| Primary analysis | 5.0 (4.3–6.3) | 7.7 (6.2–9.2) | 0.85 (0.69–1.04) | 0.1079 |

| Censored for the use of DMT | 5.3 (4.3–6.7) | 8.5 (6.5–9.5) | 0.80 (0.64–0.99) | 0.0437 |

| Excluding subjects who received HMA | 4.5 (3.8–5.5) | 7.9 (6.0–9.3) | 0.77 (0.62–0.94) | 0.0109 |

| Analysis of mature data | 5.0 (4.3–6.3) | 7.7 (6.2–9.2) | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 0.0373 |

| Censored for the use of DMT | 5.3 (4.3–6.7) | 8.6 (6.5–9.5) | 0.79 (0.65–0.98) | 0.0295 |

| Excluding subjects who received HMA | 4.4 (3.7–5.5) | 7.9 (6.0–9.3) | 0.73 (0.60–0.88) | 0.0014 |

| EFS, PFS, RFS, median (95% CI), months | ||||

| EFS | 2.1 (1.9–2.8) | 3.5 (2.5–4.1) | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.0029 |

| PFS | 2.1 (1.9–3.1) | 3.7 (2.7–4.6) | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.0036 |

| RFS | ||||

| In patients with CR | 6.7 (2.9–13.4) | 8.3 (4.6–11.4) | – | |

| In patients with cytogenetic CR | – | – | – | |

| Clinical response, n (%) | ||||

| CR + CRp | 19 (7.8) | 43 (17.8) | 2.5 (1.40–4.78)a | 0.0011 |

| Cytogenetic CR | 3/41 (7.3) | 4/40 (10.0) | 1.4 (0.22–10.24)a | 0.712 |

| Time to and duration of response, median (95% CI), months | ||||

| Time to best response (CR or CRp) | 3.7 (2.8–4.6) | 4.3 (3.8–5.1) | ||

| Duration of response (CR or CRp) | 12.9 (4.2–NE) | 8.3 (6.2–11.4) | ||

CI confidence interval, CR complete remission, CRp CR with incomplete platelet recovery, DMT disease-modifying therapy, EFS event-free survival, HMA hypomethylating agent, HR hazard ratio, NE not estimable, OR odds ratio, PFS progression-free survival, RFS relapse-free survival, TC patient’s choice of treatment with physician’s advice

aValues are odds ratios (95% CI)

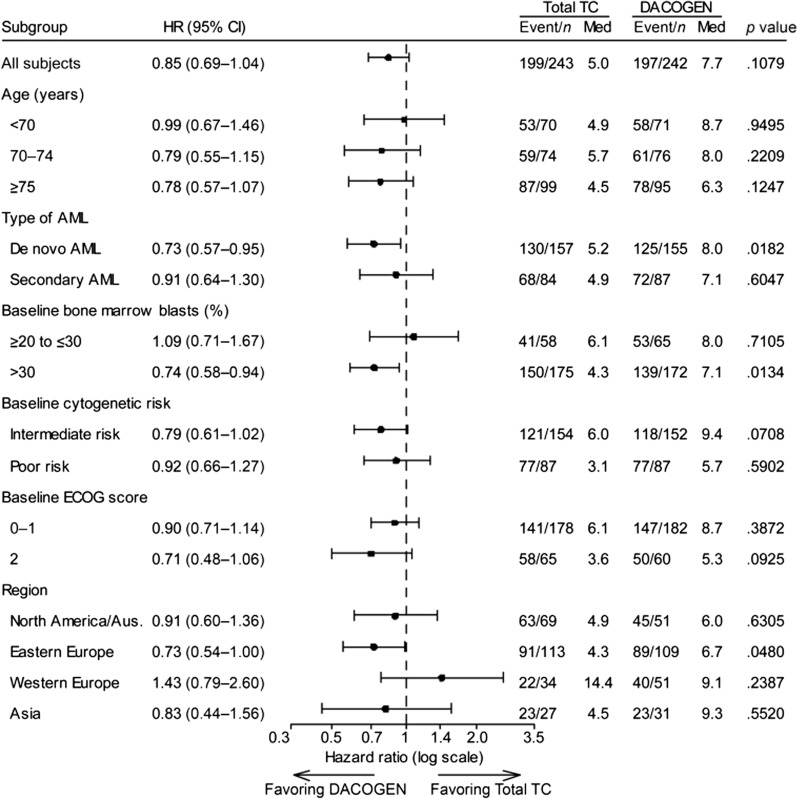

Subgroup analyses by age (65–69 vs. ≥ 70 years), ECOG performance status (0–1 vs. 2), cytogenetic risk (poor vs. intermediate), and geographic region are shown in Fig. 2 [16]. Median OS appeared to vary geographically, particularly in western Europe where median OS in the TC arm (14.4 months) was longer than in the decitabine arm.

Fig. 2.

Overall survival subgroup analysis in the DACO-16 intent-to-treat population (clinical cutoff date, 2019). The p value is based on a two-sided log-rank test stratified by age, cytogenetic risk, and ECOG performance status. AML acute myeloid leukemia, Aus Australia, CI confidence interval, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, HR hazard ratio, Med median, TC patient’s choice of treatment with physician’s advice

Results from the supportive DACO-017 trial were consistent with those from the pivotal study [15]. DACO-017 was a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 study of decitabine as first-line therapy in patients with AML aged older than 60 years. The primary efficacy endpoint (morphologic CR) was achieved in 13 of 55 patients (23.6%) with a median time to CR of 4.1 months. Median OS (the secondary endpoint) was 7.6 months (95% CI 5.7–11.5 months).

Post Hoc and Subgroup Analyses

The results of the DACO-016 trial resulted in approval of decitabine in AML in the European Union, but not in the USA. Although prespecified, the log-rank test could be considered not optimal to assess the observed survival difference because of the non-proportional hazard nature of the survival curves. Therefore, Tomeczkowski et al. conducted a sensitivity analysis of DACO-016 in which they applied the Wilcoxon test [18]. The stratified Wilcoxon test showed a significant improvement in OS with decitabine; median OS was 7.7 months (95% CI 6.2–9.2 months) in the decitabine arm compared with 5.0 months (95% CI 4.3–6.3 months; p = 0.0458) in the TC arm. Patients who achieved CR (17.8% of participants) had a median OS of 18.6 months [18].

A subgroup analysis investigated prognostic factors for outcomes in the DACO-016 trials and examined OS and responses in prespecified subgroups based on age, sex, cytogenetic risk, AML type, ECOG performance status, geographic region, bone marrow blasts, platelets, and white blood cells, based on mature data [19]. Patient characteristics that appeared to negatively influence OS were more advanced age (hazard ratio [HR] 1.560 for ≥ 75 vs. < 70 years; p = 0.0010), poorer performance status at baseline (HR 0.771 for 0 or 1 vs. 2; p = 0.0321), poor cytogenetics (HR 0.699 for intermediate vs. poor; p = 0.0010), higher bone marrow blast counts (HR 1.355 for > 50% vs. ≤ 50%; p = 0.0045), low baseline platelet counts (HR 0.775 for each additional 100 × 109/L; p = 0.0015), and high white blood cell counts (HR 1.256 for each additional 25 × 109/L; p = 0.0151). Response rates were higher in the decitabine group than the TC group in all subgroups, including patients ≥ 75 years old (OR 5.94; p = 0.0006).

Another post hoc analysis of the DACO-106 study demonstrated that decitabine significantly reduced transfusion dependence in older patients with AML compared with TC [20]. Of the patients who were red blood cell (RBC) transfusion dependent at baseline (168 patients in the decitabine arm and 162 in the TC arm) significantly more patients in the decitabine arm (n = 44 [26%]) than the TC arm (n = 21 [13%], p = 0.0026) became RBC transfusion independent, which was defined as no transfusions for at least eight consecutive weeks. The duration of RBC transfusion independence was also significantly longer in the decitabine arm than the TC arm: 17% of patients in the decitabine arm compared with 9% patients in the TC arm were RBC transfusion independent for at least 24 weeks (p = 0.0138). Results were similar in patients who were platelet transfusion dependent at baseline, with 31% of those on decitabine becoming transfusion independent compared with 13% of those on TC (p = 0.0069). Moreover, transfusion independence appeared to be associated with an increase in OS, even in the absence of CR, suggesting that CR is not required for patients to gain benefit from decitabine treatment.

In another unplanned post hoc analysis, the DACO-016 investigators selected a subset of patients with BM blasts ≥ 30% and WBC < 15 × 109/L, and compared the clinical characteristics and outcomes of these patients with data from the AML-001 trial [21]. Of the 485 patients in the DACO-016 trial, 271 (56%) met the criteria for this analysis, of whom 127 (47%) were randomized to decitabine and 144 (53%) to TC. Within this subgroup, the CR/CRi rate was 27% in patients receiving decitabine and 11% in patients receiving TC. This was associated with a significant improvement in OS in the decitabine group (median 8.6 vs. 4.7 months, HR 0.67; p = 0.0033), a relative improvement of 83% over TC. These results compare favorably with the outcomes reported in the AML-001 trial. Although comparison of two different trials is problematic, the results indicate that decitabine is another viable treatment option for older patients with higher-blast-count AML.

Real-World Data

Since September 2012, when decitabine received marketing authorization [22], several observational “real-life” studies confirmed the effectiveness of decitabine for the treatment of older patients with AML unfit for intensive chemotherapy. A retrospective, non-interventional, multicenter registration study in Belgium assessed data from 45 patients, of whom 30 (67%) had secondary AML. Median OS and PFS were 7.3 months (95% CI 2.2–11.1) and 4.1 months (95% CI 2.1–7.6), respectively. Patients who received at least four cycles (n = 21) seemed to have significantly better outcomes than patients receiving fewer than four cycles of decitabine (median OS 17.5 vs. 1.6 months, and median PFS 17.5 vs. 1.4 months, respectively). Overall, 25% of the patients who were RBC infusion dependent and 58% of those who were platelet transfusion dependent at baseline became transfusion independent [23].

Investigators pooled data from three multicenter observational studies conducted in Italy that included 306 older patients with AML (median age 75 years) who were not candidates for intensive chemotherapy [24]. These patients received a total of 1940 cycles of decitabine, a median of 5 cycles per patient. The objective response rate (ORR) was 48.4%, with 23.2% of patients achieving CR, 10.5% partial remission [PR], and 4.7% hematologic improvement. Median OS was 10.0 months in the overall patient cohort, but 11.6 months for patients with favorable-intermediate cytogenetic risk and 7.9 months for patients with adverse cytogenetic risk. Patients who achieved CR had a median OS of 22.1 months.

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare linked database, US investigators examined outcomes in older patients with AML who received a first-line hypomethylating agent [25]. They identified 2263 patients (aged ≥ 66 years) diagnosed with AML during 2005–2015 who received azacitidine (n = 1154; 51%) or decitabine (n = 1109; 49%). Median OS was 7.1 and 8.2 months (p < 0.01) for azacitidine- and decitabine-treated patients, respectively. The mortality risk was higher with azacitidine than with decitabine (HR 1.11; 95% CI 1.01–1.21; p = 0.02). The findings were similar when evaluating only patients completing at least four cycles (42% of patients treated with either azacitidine or decitabine), but they were no longer significant when evaluating those who completed a standard 7-day schedule of azacitidine (34%) versus a 5-day schedule of decitabine (66%; HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.83–1.08; p = 0.43). RBC transfusion independence was achieved in one-third of patients, with no difference between the two HMAs. Overall, there were no clinically meaningful differences between azacitidine- and decitabine-treated patients in their OS or achievement of RBC transfusion independence. However, the majority of older patients with AML did not receive the minimum of four cycles of HMA recommended to elicit clinical benefit.

Safety and Toxicity

Most patients (≥ 97%) in the registration trial had experienced a treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) at the time of the October 2009 data cutoff, and most reported at least one serious TEAE (decitabine, 80%; cytarabine, 72%; SC, 41%). The most common serious TEAEs included febrile neutropenia (decitabine, 24%; cytarabine, 16%; SC, 0%), pneumonia (decitabine, 20%; cytarabine, 16%; SC, 10%), and progressive disease (PD) (decitabine, 11%; cytarabine, 14%; SC, 7%), and the most common grade 3 or 4 TEAEs were thrombocytopenia (decitabine, 40%; cytarabine, 35%; SC, 14%) and anemia (decitabine, 34%; cytarabine, 27%; SC, 14%). Similar results were seen in the mature analysis, when data cutoff was 2010 (Table 2) [16].

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events of grade 3 or 4 in at least 10% of patients in any group (2009 clinical cutoff) [16]

| Adverse event, n (%) | TC (control) | Decitabine (n = 238) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supportive care (n = 29) | Cytarabine (n = 208) | Total TC (n = 237) | ||

| Any grade 3 or 4 adverse event | 16 (55) | 188 (90) | 204 (86) | 221 (93) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 (14) | 73 (35) | 77 (32) | 95 (40) |

| Anemia | 4 (14) | 56 (27) | 60 (25) | 80 (34) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 51 (25) | 51 (22) | 76 (32) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (3) | 41 (20) | 42 (18) | 76 (32) |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 20 (10) | 20 (8) | 47 (20) |

| Pneumonia | 4 (14) | 39 (19) | 43 (18) | 51 (21) |

| Bronchopneumonia | 3 (10) | 9 (4) | 12 (5) | 10 (4) |

| Disease progression | 2 (7) | 46 (22) | 48 (20) | 43 (18) |

| General physical health deterioration | 5 (17) | 33 (16) | 38 (16) | 30 (13) |

| Pyrexia | 3 (10) | 17 (8) | 20 (8) | 24 (10) |

| Hypokalemia | 5 (17) | 19 (9) | 24 (10) | 27 (11) |

| Dyspnea | 3 (10) | 11 (5) | 14 (6) | 16 (7) |

TC patient’s choice of treatment with physician’s advice

Fourteen patients (6%) who received decitabine recipients and 17 (8%) who received cytarabine stopped therapy because of TEAEs. In the first 30 days in treatment, 21 patients (9%) in the decitabine arm and 17 (8%) in the cytarabine arm died. Mortality after 60 days was 19.7% in the decitabine arm and 24.9% in the TC arm (cytarabine, 23%; SC, 34.5%). Overall, 77 decitabine-treated patients (32%) and 59 cytarabine-treated patients (28%) died during treatment or at least 30 days after the last study drug dose; the cause of death was a TEAE in 58 patients (24%) in the decitabine arm and 39 patients (19%) in the cytarabine arm, and PD in 16 (7%) and 17 (8%) patients, respectively. The overall death rate was lower in the decitabine arm (0.57 per patient-year; 95% CI 0.45–0.72) than in the cytarabine arm (0.73 per patient-year, 95% CI 0.56–0.94), but the rate of death due to AEs was similar in the decitabine (0.43 per patient-year; 95% CI 0.33–0.56) and cytarabine (0.48 per patient-year; 95% CI 0.34–0.66) groups.

When interpreting the safety data, it is important to note that exposure to medication was 83% longer in the decitabine arm (median 4.4 months) than the TC arm (median 2.4 months with cytarabine), in both the initial (2009) and mature (2010) analyses. Data from the two DACO trials and real-world studies show that the toxicity associated with decitabine is relatively mild and AEs are manageable [23–26], with no additional AEs report in real-world studies compared with those reported in the DACO-016 and DACO-017 trials [15, 16].

Genetics

AML has been extensively studied using whole genome sequencing technologies [27], starting with the publication of the first genome in 2008. Since then, numerous novel recurrent somatic disease alleles have been identified, including mutations of the DNA methyltransferase 3A gene (DNMT3A) and the isocitrate dehydrogenase genes (IDH1 and IDH2) [28–31]. Most of the mutations in genes encoding epigenetic modifiers are acquired early and are present in the leukemic clone. Mutations in these genes are common in older people and, together with clonal expansion of hematopoiesis, lead to an increased risk of developing hematologic cancers [32].

Genetic data are currently used for disease classification, risk stratification, and planning the clinical care of patients. The WHO added two new entities—AML with mutated RUNX1 and AML with BCR-ABL1—to its current update of the classification of myeloid neoplasms and AML, and the 2017 European LeukemiaNet recommendations added mutations in RUNX1, ASXL1, and TP53 to their risk stratification guidelines for AML [7].

Molecular alterations are presumably correlated with the therapeutic effect of HMA treatment. Mutations in DNMT3A, IDH2, ASXL1, TET2, RUNX1, CEBPA single (CEBPAsingle−mut), and TP53 are common in older patients with AML. In younger patients with AML treated with standard therapy, DNMT3A, FLT3-ITD, and TP53 mutations were associated with poor OS and EFS. On the other hand, in older patients receiving decitabine-based treatment, harboring FLT3-ITD and ASXL1 mutations, but not DNMT3A or TP53 mutations, was associated with worse outcomes (OS and EFS). CEBPAsingle−mut was also identified as an unfavorable prognostic factor, whereas CEBPA double mutation (CEBPAdouble−mut) was not [33].

In various studies, patients with AML with an unfavorable-risk cytogenetic profile and TP53 mutations have poorer outcomes when treated with standard chemotherapy [34, 35]. Although clinical responses vary, recent studies have demonstrated that the presence of adverse-risk karyotypes or TP53 mutations does not have a negative effect on sensitivity to HMA treatment [15, 36, 37].

TP53 Mutations

TP53 aberrations seem to predict favorable responses to hypomethylating treatment with decitabine. Becker et al. analyzed outcomes associated with chromosome 17p loss or TP53 gene mutations in unfit elderly patients with AML [38]. In that study, 25 of 178 patients had loss of 17p, of whom 24 had a complex (CK+) and 21 a monosomal karyotype (MK+). Patients with 17p loss showed a better CR, PR, and antileukemic effect (ALE). However, there was no significant different in OS between patients with or without loss of 17p, and this was also true in the subgroups of patients with CK+ or MK+. Eight of 45 patients had TP53 mutations, and five of these patients also had 17p loss. CR, PR, and ALE rates were similar in patients with TP53 mutations and those with wild-type TP53, but OS appeared to be worse in patients with mutated TP53 (p = 0.036) [38].

HMA treatment can probably partly overcome the adverse prognostic impact of a TP53 mutation. A registry-based analysis by Middeke et al. also found that outcomes were not negatively influenced by a TP53 mutation [39]. These researchers analyzed data from 311 patients with AML treated with decitabine, and found that ORR was 30% and median OS was 4.7 months. Patients on first-line decitabine treatment showed better responses than patients who had relapsed/refractory AML (ORR 38% versus 21%), and a slightly longer OS (median 5.8 months versus 3.9 months). Next generation sequencing was undertaken in 180 patients, and 20 (11%) had a TP53 mutation. Response rates and in this real-world data also the survival were comparable between patients with or without TP53 mutations [39].

Monosomal Karyotype

Monosomal karyotype-positive (MK+) AML (i.e., the presence of at least two autosomal monosomies or one autosomal monosomy with at least one structural chromosomal abnormality) is associated with poor prognosis, but several studies suggest a potential positive effect of decitabine in patients with MK+ AML. The DACO-016 investigators conducted a post hoc analysis to determine the effects of decitabine versus TC on outcomes in MK+ patients [40, 41]. A phase 2 trial of decitabine as first-line treatment for older patients with AML showed a higher ORR, and comparable OS, in MK+ patients than MK− patients with abnormal cytogenetics [42].

In DACO-016, 64 of 485 patients were MK+ (decitabine, n = 33; TC, n = 31) and 99 were MK− with poor-risk cytogenetics (decitabine, n = 49; TC, n = 50). In MK+ patients, CR/CRi was 27% in the decitabine arm and 3% in the TC arm (p = 0.0132), ORR was 36% and 3%, respectively (p = 0.0013), and PFS was 2.6 and 1.3 months, respectively (HR 0.53 [95% CI 0.31–0.90]; p = 0.0181). There was a trend toward longer OS in the decitabine arm compared with the TC arm (median OS 6.3 vs. 2.6 months; HR 0.67 [95% CI 0.39–1.15]; p = 0.141), which was significant when the analysis was censored for the initiation of follow-up treatment (median OS 6.3 vs. 2.6 months; HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.29–0.93; p = 0.0253).

In MK− patients with poor-risk cytogenetics, DACO-016 investigators found no difference between patients who received decitabine or TC in CR/CRi rate (decitabine arm 18% vs. TC 0%; p = 0.262), ORR (decitabine 20% vs. TC 12%; p = 0.287), or median PFS (decitabine 2.4 months vs. TC 2.2 months; p = 0.576). Even after censoring at the time of subsequent therapy, there was also no difference in median OS between the decitabine and TC groups in this subpopulation (5.0 vs. 5.0 months; p = 0.789).

These results are similar to data from a subgroup analysis of a phase 3 study of decitabine treatment in patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) [43]. Investigators of that study concluded that decitabine treatment may overcome the poor prognosis of patients with MK+ AML and offer a new therapeutic option for these patients who are difficult to treat.

Gene Derepression

Gene derepression and reactivation probably explains the superiority of HMA over cytarabine in patients with AML with chromosomal deletions. Investigators discovered that decitabine induced transcriptome changes in AML cell lines with or without a deletion of chromosomes 7q, 5q, or 17p. Treating these cell lines with HMA caused an upregulation of several hemizygous tumor suppressor genes, derepressing endogenous retrovirus (ERV)3–1 and increasing H3K4me3 levels. Decitabine reactivated multiple transposable elements, such as double-strand RNA sensor RIG-I and interferon regulatory factor 7. Similar changes were observed in experiments on peripheral blood blasts from patients with AML receiving in vivo treatment with decitabine [44].

Response and Resistance to Decitabine

Although decitabine monotherapy has shown clear efficacy in patients with AML, many patients will not respond (showing primary resistance) or will lose response (showing adaptive or secondary resistance). The mechanisms underlying development of resistance to decitabine have been widely investigated but not completely clarified [45, 46]. There are also no confirmed biomarkers that can predict response to decitabine, although there are indications that fetal hemoglobin induction during decitabine treatment may be associated with prognosis [47, 48]. On the other hand, clinical resistance to decitabine results from the complex interaction of cellular, disease-related and individual patient characteristics [49].

The supposed mechanism of action of decitabine is DNA hypomethylation of leukemic cells and the subsequent re-expression of silenced genes. DNA hypermethylation is a feature of leukemic cells and its downregulation may be a sign of decitabine activity. In fact, response to HMAs has been correlated generically with hypomethylation. Studies have demonstrated that the modulation of methylation induced by decitabine is regional and involves non-promoter as well promoter regions, but it is hard to identify specific baseline methylation biomarkers predictive of response. The expression of nucleotide uptake and activating enzymes like cytidine deaminase (CDA) and deoxycytidine kinase (DCK) is very heterogeneous in AML and has been correlated with in vitro and in vivo response to decitabine. More recently, baseline levels of triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 have been correlated with clinical response to decitabine in patients with AML. A possible approach to overcoming decitabine resistance could thus be to target pathways and molecules other than those involved in DNA methylation [50, 51].

Combination Therapy

To increase the likelihood and duration of response, several novel agents are being combined with a backbone of decitabine therapy in AML. The mechanisms of action of these novel agents are quite heterogeneous, and although some have been used empirically, in other cases, there is preclinical evidence suggesting possible clinical synergy with decitabine.

Decitabine has been combined with histone deacetylase inhibitors of various types. In addition to DNA methylation, the epigenetic alterations that occur in AML may be caused by histone modifications. Chromatin rearrangements are driven by the cooperative function of enzymes regulating histones; therefore, the first agents thought to increase the efficacy of HMAs were histone deacetylase inhibitors. Despite a solid scientific rationale and promising preclinical evidence, the combination of decitabine with valproic acid or vorinostat did not show any advantage in terms of responses or survival when used clinically in patients with AML [52–54].

Decitabine has been demonstrated to increase in the expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1), and programmed cell death ligand 1 and 2 (PD-L1 and PD-L2) in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that decitabine plus an immune checkpoint inhibitor may be an effective combination. Such combinations have been evaluated in clinical trials in patients with refractory/relapsed AML, including decitabine with the anti-PD-1 antibody PDR001 (NCT03066648), ipilimumab (NCT02890329), and pembrolizumab (NCT02996474), but the results were inconclusive. In addition, the anti-Tim3 antibody sabatolimab has been evaluated in combination with decitabine in de novo patients with AML in a phase 1b study with encouraging results [55].

Venetoclax is an orally bioavailable small-molecule inhibitor that selectively targets Bcl-2 and has shown great efficacy in AML, in combination with low-dose cytarabine and HMAs [52, 56]. Larger clinical trials evaluating decitabine and venetoclax combination therapy are ongoing, and HMAs plus venetoclax are at present standard of care for elderly patients with AML not eligible for intensive chemotherapy.

Although only preliminary data are available for the combination of decitabine with other molecules like magrolimab (anti-CD47), APR246, and the IDH inhibitors ivosidenib and enasidenib, the concept of HMA-based doublet and triplet regimens as first-line therapy of AML is quite clearly gaining ground, and we expect to see more combinations of decitabine to optimize treatment of patients who are not candidates for intensive chemotherapy. Besides possible gains in efficacy, it is important that the side effects of such combinations should remain manageable in a population prone to multiple comorbidities.

Conclusion

Decitabine offers an important treatment option for the many patients with AML who are unfit to receive more intensive combination therapies. In this context, decitabine offers a meaningful improvement in survival, with manageable toxicity. Whether patients with TP53 mutations have more benefit from HMAs is a matter of debate since existing data are inconclusive. Alternative schemes, such as 10-day administration, are currently being investigated. So far, the 5-day scheme is still the recommended dosage to apply in the EU [10]. Further research is needed to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from decitabine treatment, as well as predictors of treatment resistance, and to identify potentially effective combinations with decitabine to further enhance the benefits of this treatment.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this review including the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees was funded by Janssen-Cilag International N.V. (B-2340 Beerse, Belgium).

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by medical writer Mirjam Bedaf, MSc, medical advisor at Janssen-Cilag International N.V Richard Milek, PhD, and René Molenaar (Springer Healthcare). This assistance was funded by Janssen-Cilag International N.V. (B-2340 Beerse, Belgium).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All named authors contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and writing. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Valeria Santini, Michael Lübbert, Agnieszka Wierzbowska and Gert J. Ossenkoppele declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised due to update in article text.

Change history

7/31/2023

This article was updated due to addition of video abstract.

Change history

2/15/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12325-021-02033-w

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute Surveillance EaERP. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975–2017: Leukemia. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2017/browse_csr.php?sectionSEL=13&pageSEL=sect_13_table.16. Accessed 5 Mar 2021.

- 2.Rodriguez-Abreu D, Bordoni A, Zucca E. Epidemiology of hematological malignancies. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(Suppl 1):i3–i8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sant M, Allemani C, Tereanu C, et al. Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood. 2010;116(19):3724–3734. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juliusson G, Lazarevic V, Horstedt AS, Hagberg O, Hoglund M, Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry Group Acute myeloid leukemia in the real world: why population-based registries are needed. Blood. 2012;119(17):3890–3899. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-379008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang K, Earle CC, Foster T, Dixon D, Van Gool R, Menzin J. Trends in the treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(11):943–955. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A, Andersson TM, Rachet B, Bjorkholm M, Lambert PC. Survival and cure of acute myeloid leukaemia in England, 1971–2006: a population-based study. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(4):509–516. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100(13):4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Angelis R, Minicozzi P, Sant M, et al. Survival variations by country and age for lymphoid and myeloid malignancies in Europe 2000–2007: results of EUROCARE-5 population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(15):2254–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heuser M, Ofran Y, Boissel N, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(6):697–712. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimwade D, Walker H, Harrison G, et al. The predictive value of hierarchical cytogenetic classification in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): analysis of 1065 patients entered into the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML11 trial. Blood. 2001;98(5):1312–1320. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vos D, van Overveld W. Decitabine: a historical review of the development of an epigenetic drug. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(Suppl 1):3–8. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-0008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contieri B, Duarte BKL, Lazarini M. Updates on DNA methylation modifiers in acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(4):693–701. doi: 10.1007/s00277-020-03938-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Momparler RL. Molecular, cellular and animal pharmacology of 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine. Pharmacol Ther. 1985;30(3):287–299. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(85)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cashen AF, Schiller GJ, O'Donnell MR, DiPersio JF. Multicenter, phase II study of decitabine for the first-line treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):556–561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, et al. Multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2670–2677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nieto M, Demolis P, Behanzin E, et al. The European Medicines Agency Review of Decitabine (Dacogen) for the treatment of adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: summary of the scientific assessment of the committee for medicinal products for human use. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):692–700. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomeczkowski J, Lange A, Guntert A, et al. Converging or crossing curves: untie the Gordian knot or cut it? Appropriate statistics for non-proportional hazards in decitabine DACO-016 study (AML) Adv Ther. 2015;32(9):854–862. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer J, Arthur C, Delaunay J, et al. Multivariate and subgroup analyses of a randomized, multinational, phase 3 trial of decitabine vs treatment choice of supportive care or cytarabine in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and poor- or intermediate-risk cytogenetics. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He J, Xiu L, De Porre P, Dass R, Thomas X. Decitabine reduces transfusion dependence in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results from a post hoc analysis of a randomized phase III study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(4):1033–1042. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.951845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadia TM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, et al. Decitabine improves outcomes in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia and higher blast counts. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(7):E139–E141. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European Medicines Agency. Dacogen (decitabine): Summary of Product Characteristics. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/dacogen-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 5 Mar 2021.

- 23.Meers S, Bailly B, Vande Broek I, et al. Real-world data confirming the efficacy and safety of decitabine in acute myeloid leukaemia—results from a retrospective Belgian registry study. Acta Clin Belg. 2021;76(2):98–105. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2019.1665233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bocchia M, Candoni A, Borlenghi E, et al. Real-world experience with decitabine as a first-line treatment in 306 elderly acute myeloid leukaemia patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(4):447–455. doi: 10.1002/hon.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeidan AM, Wang R, Wang X, et al. Clinical outcomes of older patients with AML receiving hypomethylating agents: a large population-based study in the United States. Blood Adv. 2020;4(10):2192–2201. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fili C, Candoni A, Zannier ME, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of decitabine in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): a multicenter real-world experience. Leuk Res. 2019;76:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shivarov V, Bullinger L. Expression profiling of leukemia patients: key lessons and future directions. Exp Hematol. 2014;42(8):651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Ley TJ, Miller C, et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dohner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1136–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(4):309–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bullinger L, Dohner K, Dohner H. Genomics of acute myeloid leukemia diagnosis and pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(9):934–946. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ni J, Hong J, Long Z, Li Q, Xia R, Zeng Q. Mutation profile and prognostic relevance in elderly patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia treated with decitabine-based chemotherapy. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020;42(6):849–857. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez-Pol S, Ma L, Ohgami RS, Arber DA. Immunohistochemistry for p53 is a useful tool to identify cases of acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia-related changes that are TP53 mutated, have complex karyotype, and have poor prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(3):382–392. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGraw KL, Nguyen J, Komrokji RS, et al. Immunohistochemical pattern of p53 is a measure of TP53 mutation burden and adverse clinical outcome in myelodysplastic syndromes and secondary acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2016;101(8):e320–e323. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.143214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blum W, Garzon R, Klisovic RB, et al. Clinical response and miR-29b predictive significance in older AML patients treated with a 10-day schedule of decitabine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(16):7473–7478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002650107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welch JS, Petti AA, Miller CA, et al. TP53 and decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(21):2023–2036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becker H, Pfeifer D, Ihorst G, et al. Monosomal karyotype and chromosome 17p loss or TP53 mutations in decitabine-treated patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(7):1551–1560. doi: 10.1007/s00277-020-04082-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Middeke JM, Teipel R, Rollig C, et al. Decitabine treatment in 311 patients with acute myeloid leukemia: outcome and impact of TP53 mutations—a registry based analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62(6):1432–1440. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1864354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wierzbowska A, Wawrzyniak E, Pluta A, et al. Decitabine improves response rate and prolongs progression-free survival in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and with monosomal karyotype: a subgroup analysis of the DACO-016 trial. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(5):E125–E127. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wierzbowska A, Wawrzyniak E, Siemieniuk-Rys M, et al. Concomitance of monosomal karyotype with at least 5 chromosomal abnormalities is associated with dismal treatment outcome of AML patients with complex karyotype—retrospective analysis of Polish Adult Leukemia Group (PALG) Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(4):889–897. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1219901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lubbert M, Ruter BH, Claus R, et al. A multicenter phase II trial of decitabine as first-line treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia judged unfit for induction chemotherapy. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):393–401. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.048231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lubbert M, Suciu S, Hagemeijer A, et al. Decitabine improves progression-free survival in older high-risk MDS patients with multiple autosomal monosomies: results of a subgroup analysis of the randomized phase III study 06011 of the EORTC Leukemia Cooperative Group and German MDS Study Group. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(2):191–199. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greve G, Schuler J, Gruning BA, et al. Decitabine induces gene derepression on monosomic chromosomes: in vitro and in vivo effects in adverse-risk cytogenetics AML. Cancer Res. 2021;81(4):834–846. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stomper J, Lubbert M. Can we predict responsiveness to hypomethylating agents in AML? Semin Hematol. 2019;56(2):118–124. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stomper J, Rotondo JC, Greve G, Lubbert M. Hypomethylating agents (HMA) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: mechanisms of resistance and novel HMA-based therapies. Leukemia. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01218-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lubbert M, Ihorst G, Sander PN, et al. Elevated fetal haemoglobin is a predictor of better outcome in MDS/AML patients receiving 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (Decitabine) Br J Haematol. 2017;176(4):609–617. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stomper J, Ihorst G, Suciu S, et al. Fetal hemoglobin induction during decitabine treatment of elderly patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia: a potential dynamic biomarker of outcome. Haematologica. 2019;104(1):59–69. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.187278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao C, Jia B, Wang M, et al. Multi-dimensional analysis identifies an immune signature predicting response to decitabine treatment in elderly patients with AML. Br J Haematol. 2020;188(5):674–684. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oellerich T, Schneider C, Thomas D, et al. Selective inactivation of hypomethylating agents by SAMHD1 provides a rationale for therapeutic stratification in AML. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3475. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11413-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan P, Frankhouser D, Murphy M, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling in decitabine-treated patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(12):2466–2474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DiNardo CD, Pratz K, Pullarkat V, et al. Venetoclax combined with decitabine or azacitidine in treatment-naive, elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2019;133(1):7–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-08-868752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirschbaum M, Gojo I, Goldberg SL, et al. A phase 1 clinical trial of vorinostat in combination with decitabine in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2014;167(2):185–193. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lubbert M, Grishina O, Schmoor C, et al. Valproate and retinoic acid in combination with decitabine in elderly nonfit patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of a multicenter, randomized, 2 × 2, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(3):257–270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brunner AM, Esteve J, Porkka K, et al. Efficacy and safety of sabatolimab (MBG453) in combination with hypomethylating agents in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: updated results from a phase Ib study. In: 63rd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. 2020.

- 56.Wei AH, Montesinos P, Ivanov V, et al. Venetoclax plus LDAC for newly diagnosed AML ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Blood. 2020;135(24):2137–2145. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020004856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.